An Occupational Heat–Health Warning System for Europe: The HEAT-SHIELD Platform

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- It should be personalized; that is, based on the physical demands of the job as well as on workers’ physical, clothing, and behavioral characteristics and on the work environment;

- it should include short-term suggestions useful to help heat adaptation for workers;

- it should contain long-term heat risk information for planning/organizing work, which is useful for employers, organizations, and operators in charge of safeguarding health and productivity in various occupational areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Weather Forecast Model

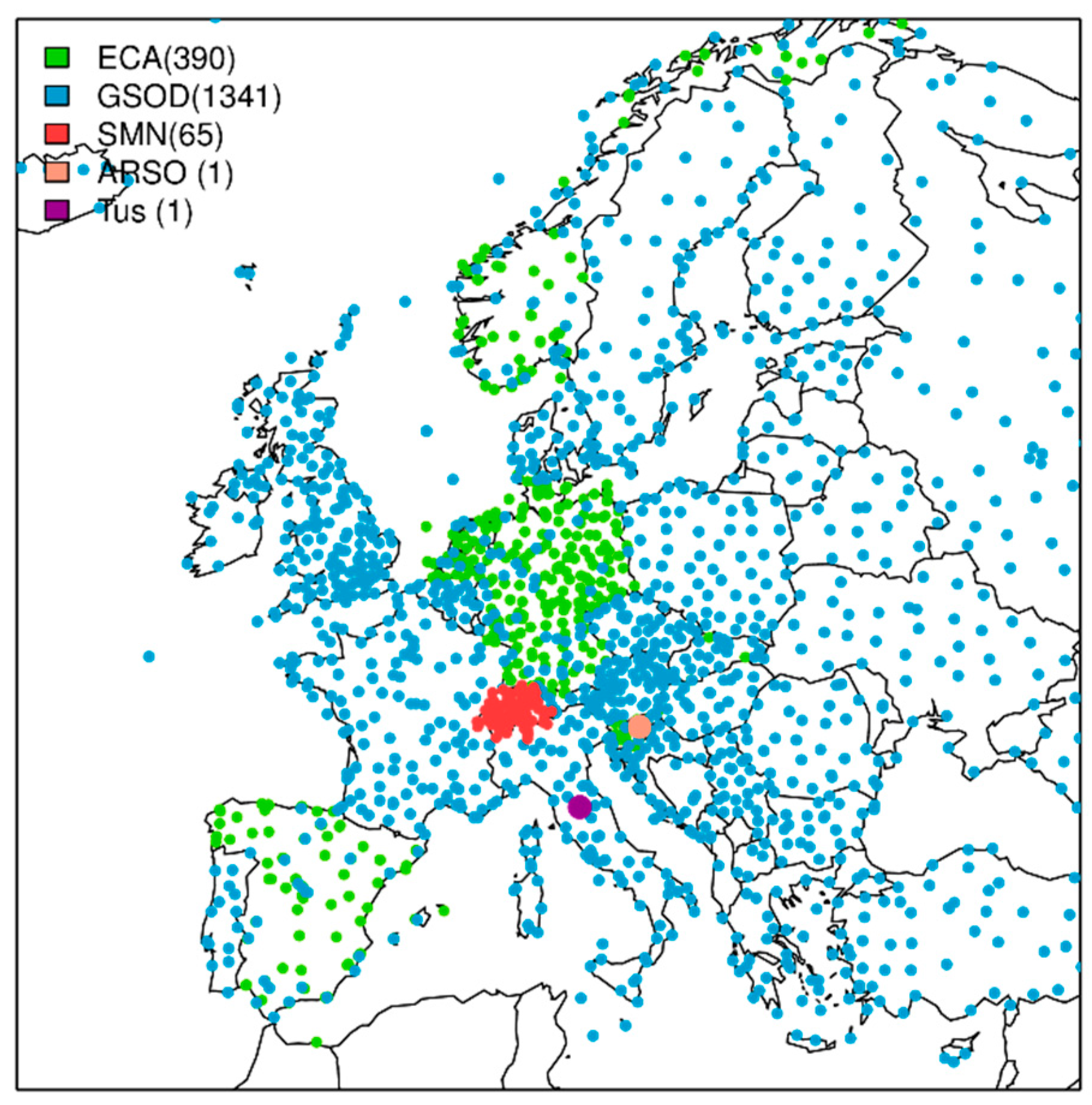

- The European Climate Assessment and Dataset project (ECA & D) [31] was the primary source for the observational dataset. There is, however, a limited number of stations with non-standard parameters such as humidity and wind (see green points in Figure 1). Thus, the following datasets were used to complete the full set of stations.

- Dataset of the Global Surface Summary of the Day (GSOD, see blue points in Figure 1) from the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Stations exceeding more than 20% of missing values in ECA & D and GSOD in the period between 1996 and 2016 were removed from the dataset.

- A couple of stations from HEAT-SHIELD case studies were included in the set of stations: Data from one station in Celje (Slovenia), near the Odelo d.o.o. manufacturing plant [33], provided by the Slovenian Environment Agency (ARSO), and from one station in Arezzo (Tuscany, Italy) provided by Regional Service of Tuscany (CFR).

2.2. Heat Stress Indicator

2.3. HEAT-SHIELD Platform Outputs

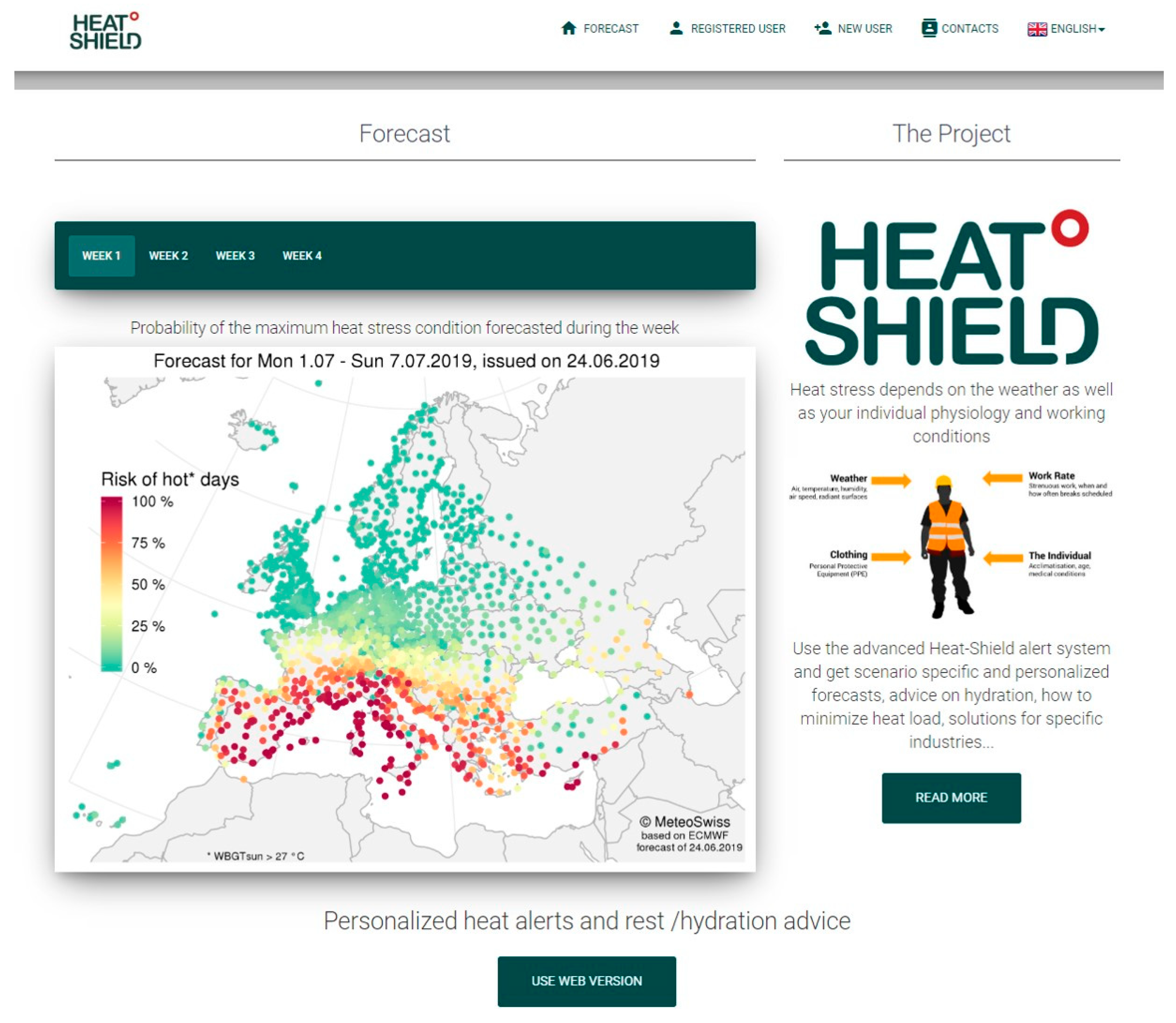

2.3.1. Non-Customized HEAT-SHIELD Platform Outputs

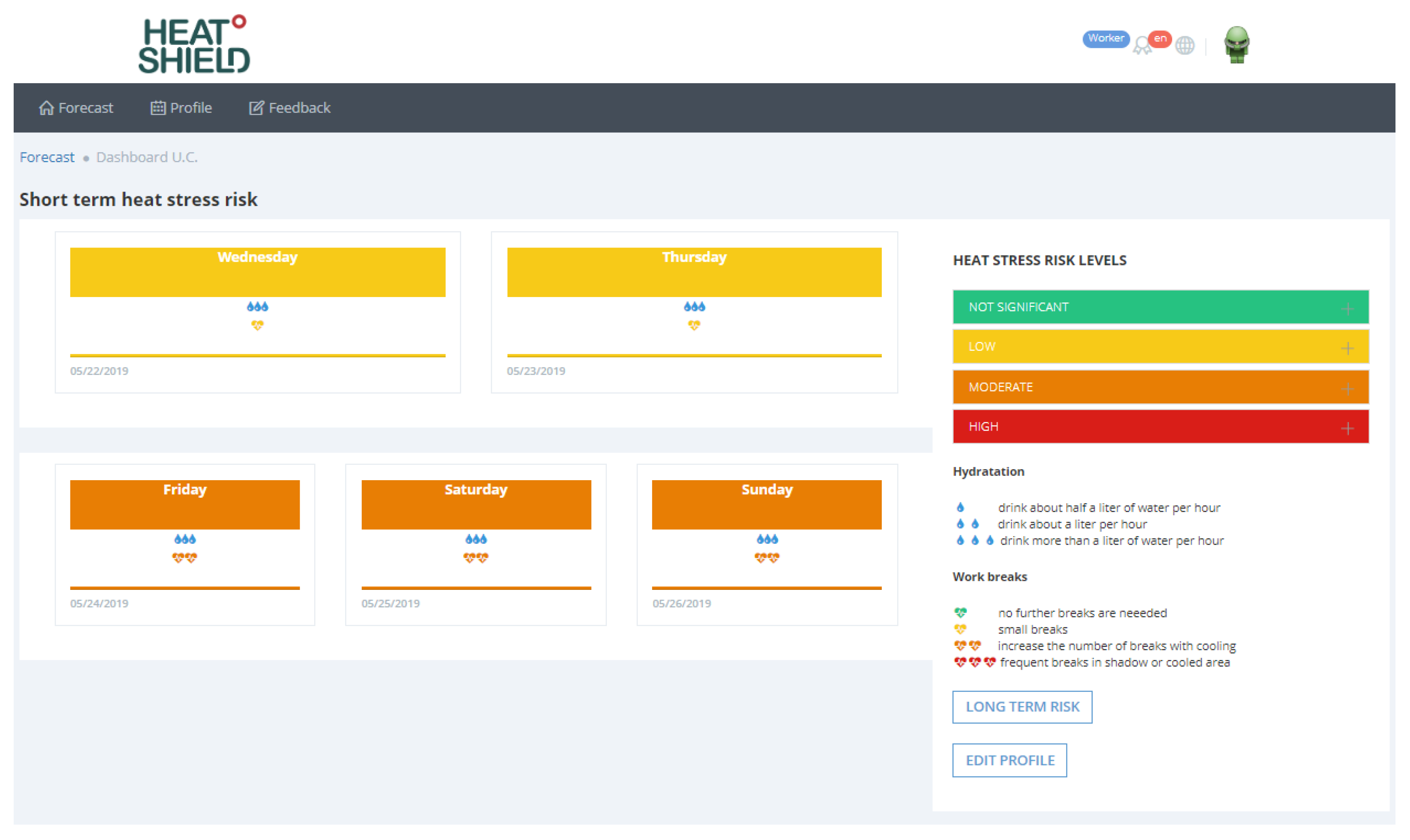

2.3.2. Customized HEAT-SHIELD Platform Outputs

- Not significant: No special precautions are required and no further breaks than usual are needed.

- Low: You should be able to maintain normal activities. You may experience heat strain (generally low) and increased sweating. Consider clothing adjustment and drink more than normal.

- Moderate: Your water needs will be high. Increase the number of breaks (include small breaks with cooling) and drink frequently. Remember to rehydrate after work/exercise: Be aware that thirst is usually not a sufficient indicator when sweating is high. If this risk level is forecasted during the first summer days, pay extra attention to increase drinking and keep a good hydration status (drink/rehydrate with your meals) outside working hours. Consider adjusting the timing of activities (heavy physical tasks) to the cooler period of the day.

- High: This level is associated with severe heat stress. It is strongly suggested to adjust work—use active cooling, schedule frequent breaks in shadowed or cool areas where you can hydrate. Additional drinking is required (water needs may be more than 1 L/h). If possible, after consulting your doctor, add mineral salts to your meals. Consider adjusting the timing of activities (moderate–heavy physical tasks) to the cooler period of the day.

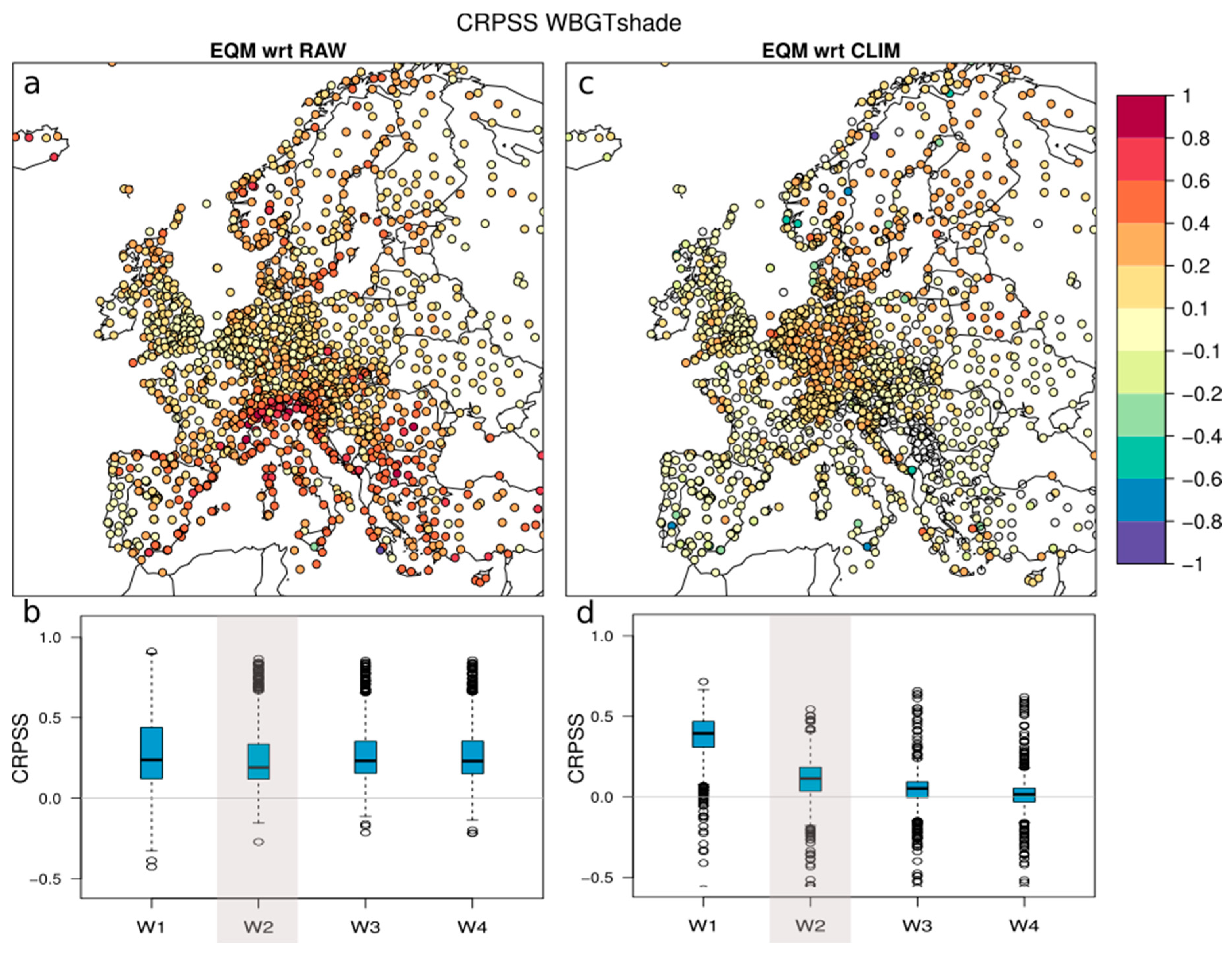

2.3.3. Forecast Verification

3. Results

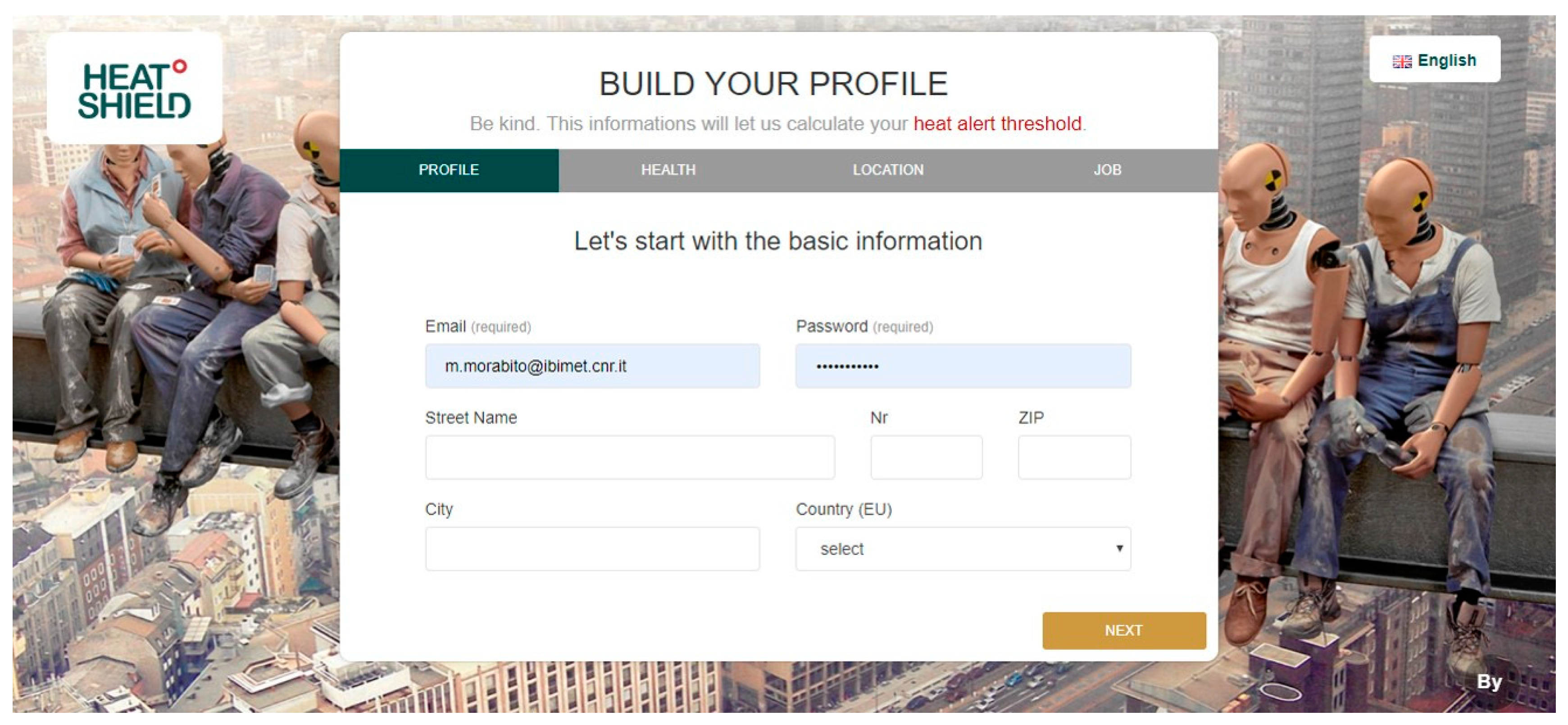

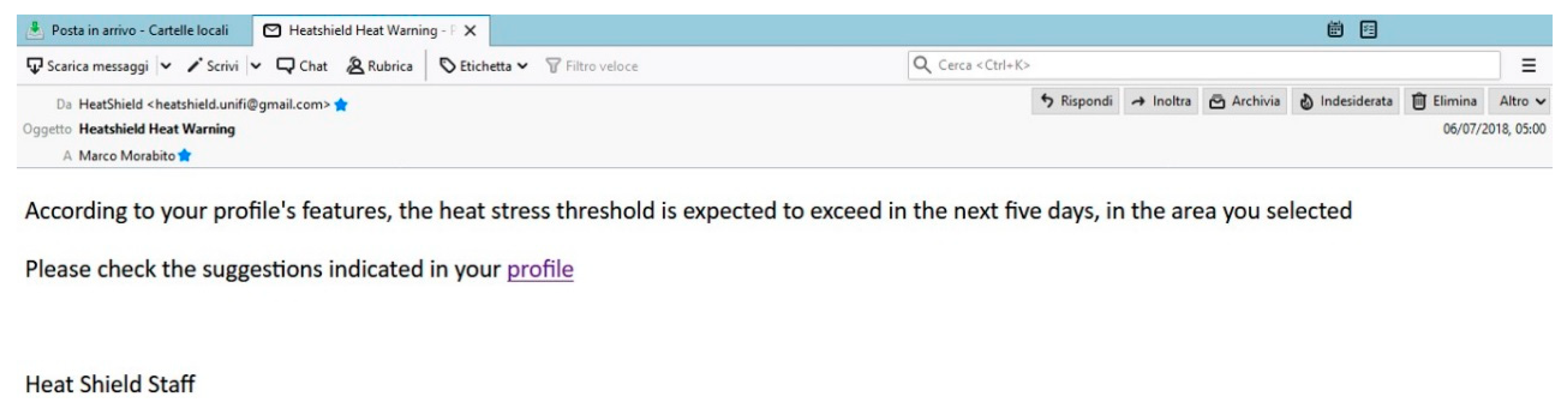

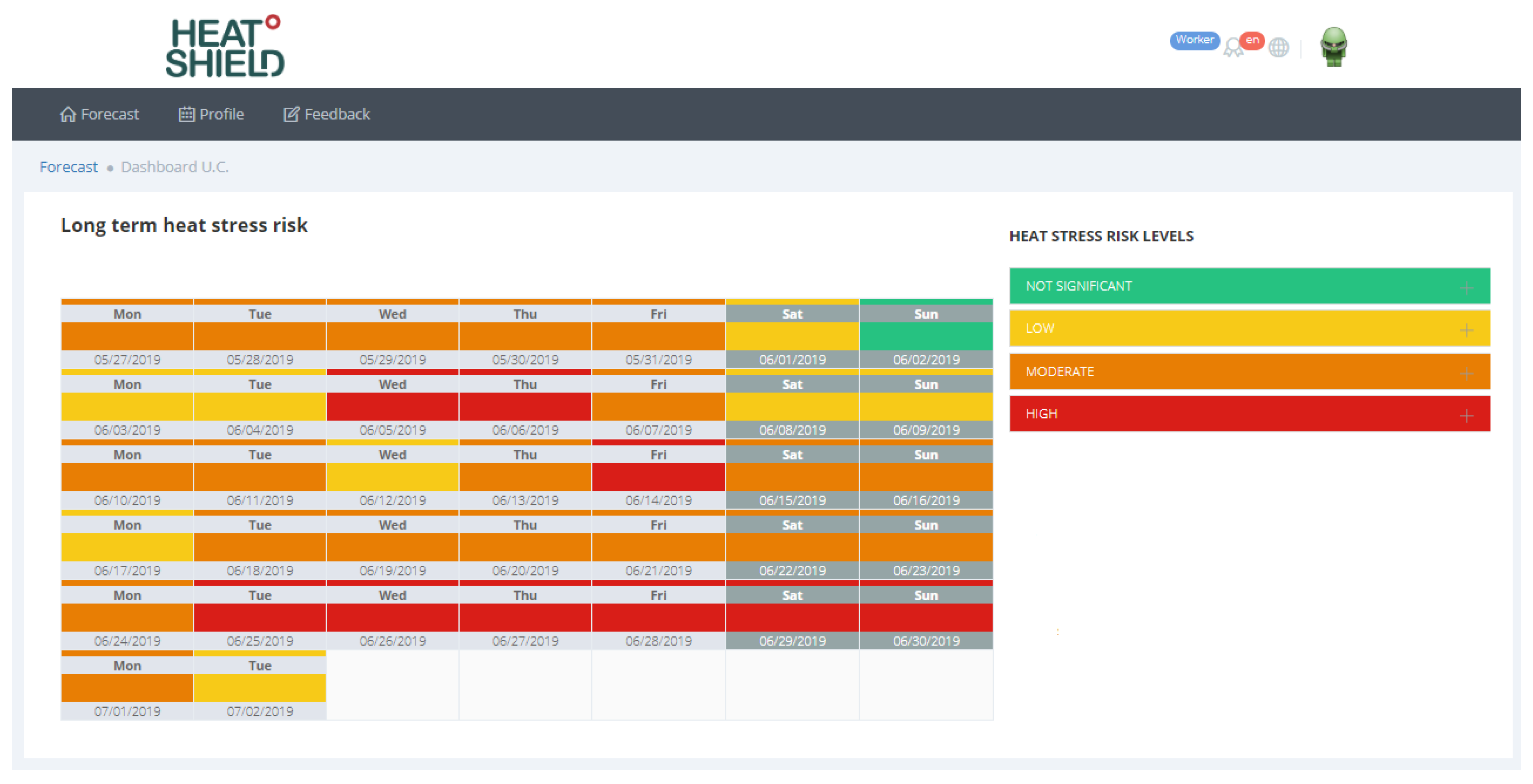

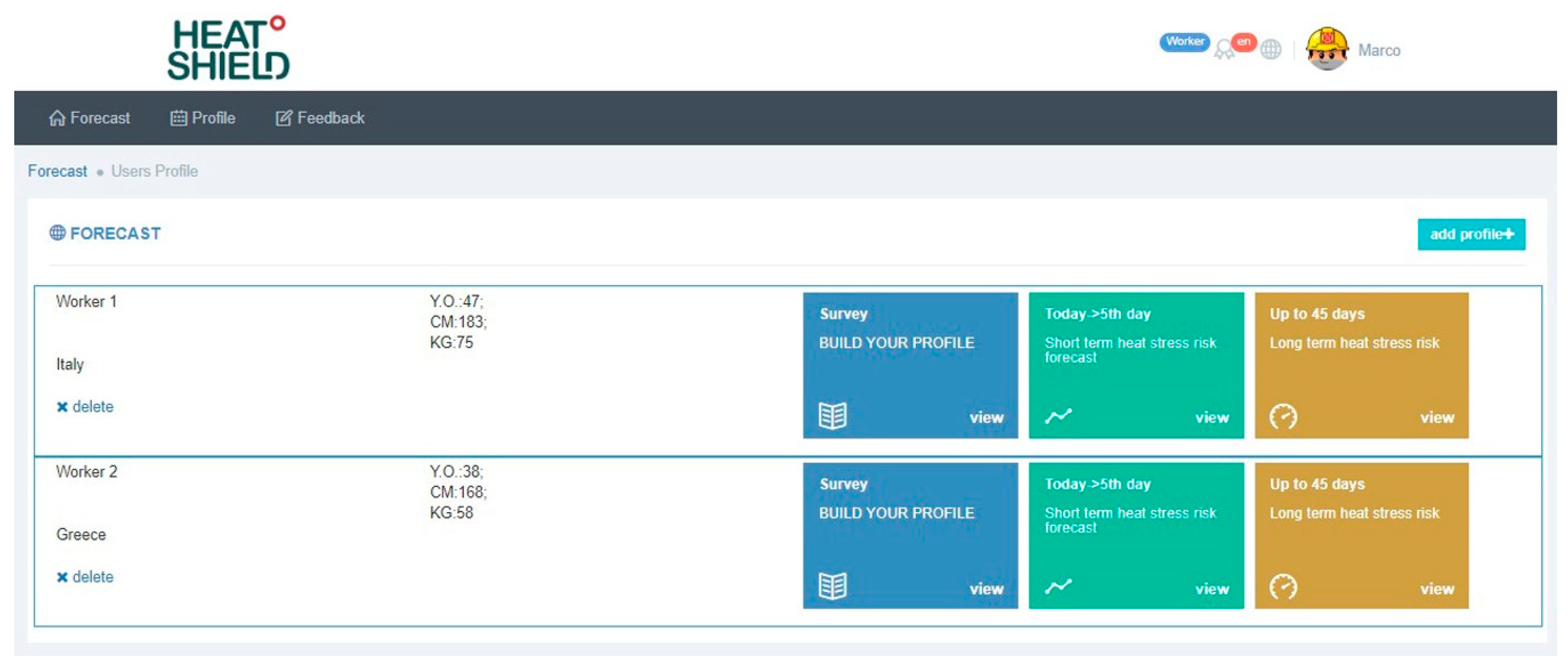

3.1. HEAT-SHIELD Platform Interface and Outputs

- Height (cm) and weight (kg);

- The location, which must be chosen by the user after indicating the exact address for which the forecast is need and double clicking on the available shield (one of the 1798 stations) nearest and with similar altitude to the location of interest;

- The physical activity level (low, moderate, high, and very high);

- The work environment (outdoors in the sun or shade);

- The type of clothing or PPE worn during work.

3.2. WBGT Forecast Verification

4. Discussion

- the HEAT-SHIELD platform is multilingual.

- The local-heat-stress-risk forecast is “customized” based on:

- ○

- the worker’s physical characteristics (specifically height and weight),

- ○

- the physical activity level,

- ○

- the clothing or PPE worn during work,

- ○

- the work environment (outdoors in the sun or shade),

- ○

- also taking into account whether the worker is acclimatized or not to the heat.

- The short-term heat risk forecast (5-day forecasts) includes behavioral recommendations related to how much hydration (water intake) and rest (work breaks) during the worst (in term of heat stress) hour of the day.

- Long-term heat risk forecasts are available up to just over one month (46 days).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mora, C.; Dousset, B.; Caldwell, I.R.; Powell, F.E.; Geronimo, R.C.; Bielecki, C.R.; Counsell, C.W.W.; Dietrich, B.S.; Johnston, E.T.; Louis, L.V.; et al. Global risk of deadly heat. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanueva, A.; Kotlarski, S.; Fischer, A.M.; Flouris, A.D.; Kjellstrom, T.; Lemke, B.; Nybo, L.; Schwierz, C.; Liniger, M.A. Escalating environmental heat exposure—A future threat for the European workforce. Reg. Environ. Chang. under review.

- Xiang, J.; Bi, P.; Pisaniello, D.; Hansen, A. Health impacts of workplace heat exposure: An epidemiological review. Ind. Health 2014, 52, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Climate Change and Labour: Impacts of Heat in the Workplace. Climate Change, Workplace Environmental Conditions, Occupational Health Risks, and Productivity—An Emerging Global Challenge to Decent Work, Sustainable Development and Social Equity; Climate Vulnerable Forum Secretariat, United Nations Development Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---gjp/documents/publication/wcms_476194.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Flouris, A.D.; Dinas, P.C.; Ioannou, L.G.; Nybo, L.; Havenith, G.; Kenny, G.P.; Kjellstrom, T. Workers’ health and productivity under occupational heat strain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e521–e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellstrom, T.; Gabrysch, S.; Lemke, B.; Dear, K. The ‘Hothaps’ programme for assessing climate change impacts on occupational health and productivity: An invitation to carry out field studies. Glob. Health Act. 2009, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takakura, J.; Fujimori, S.; Takahashi, K.; Hijioka, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Honda, Y.; Masui, T. Cost of preventing workplace heat-related illness through worker breaks and the benefit of climate-change mitigation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 064010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanos, J.; Vecellio, D.J.; Kjellstrom, T. Workplace heat exposure, health protection, and economic impacts: A case study in Canada. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, G.R.; Bessemoulin, P.; Ebi, K.L.; Menne, B. Heatwaves and Health: Guidance on Warning-System Development; WMO-No. 1142; World Meteorological Organization and World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-92-63-11142-5. Available online: http://www.who.int/globalchange/publications/WMO_WHO_Heat_Health_Guidance_2015.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Roelofs, C. Without warning: Worker deaths from heat 2014–2016. New Solut. 2018, 28, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, G.S.; Linares, C.; Ayuso, A.; Kendrovski, V.; Boeckmann, M.; Diaz, J. Heat-health action plans in Europe: Challenges ahead and how to tackle them. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, M.; Crisci, A.; Moriondo, M.; Profili, F.; Francesconi, P.; Trombi, G.; Bindi, M.; Gensini, G.F.; Orlandini, S. Air temperature-related human health outcomes: Current impact and estimations of future risks in Central Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 441, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heudorf, U.; Schade, M. Heat waves and mortality in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2003–2013: What effect do heat–health action plans and the heat warning system have? Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014, 47, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binazzi, A.; Levi, M.; Bonafede, M.; Bugani, M.; Messeri, A.; Morabito, M.; Marinaccio, A.; Baldasseroni, A. Evaluation of the impact of heat stress on the occurrence of occupational injuries: Meta-analysis of observational studies. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 62, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Rood, R.B.; Michailidis, G.; Oswald, E.M.; Schwartz, J.D.; Zanobetti, A.; Ebi, K.L.; O’Neill, M.S. Comparing exposure metrics for classifying ‘dangerous heat’ in heat wave and health warning systems. Envrion. Int. 2012, 46, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, M.; Crisci, A.; Messeri, A.; Capecchi, V.; Modesti, P.A.; Gensini, G.F.; Orlandini, S. Environmental temperature and thermal indices: What is the most effective predictor of heat-related mortality in different geographical contexts? Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 961750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanueva, A.; Burgstall, A.; Kotlarski, S.; Messeri, A.; Morabito, M.; Flouris, A.; Nybo, L.; Spirig, C.; Schwierz, C. Overview of existing heat-health warning systems in Europe. Int. J. Envrion. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, G.P.; Wilson, T.E.; Flouris, A.D.; Fujii, N. Heat exhaustion. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 157, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIOSH. NIOSH Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments; Jacklitsch, B., Williams, W.J., Musolin, K., Coca, A., Kim, J.-H., Turner, N., Eds.; DHHS (NIOSH) Publication 2016-106; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2016-106/pdfs/2016-106.pdf?id=10.26616/NIOSHPUB2016106 (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Piil, J.F.; Lundbye-Jensen, J.; Christiansen, L.; Ioannou, L.; Tsoutsoubi, L.; Dallas, C.N.; Mantzios, K.; Flouris, A.D.; Nybo, L. High prevalence of hypohydration in occupations with heat stress-Perspectives for performance in combined cognitive and motor tasks. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, G.P.; Poirier, M.P.; Metsios, G.S.; Boulay, P.; Dervis, S.; Friesen, B.J.; Malcolm, J.; Sigal, R.J.; Seely, A.J.; Flouris, A.D. Hyperthermia and cardiovascular strain during an extreme heat exposure in young versus older adults. Temperature 2017, 4, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piil, J.F.; Mikkelsen, C.J.; Junge, N.; Morris, N.B.; Nybo, L. Heat Acclimation Does Not Protect Trained Males from Hyperthermia-Induced Impairments in Complex Task Performance. Int. J. Envrion. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HEAT-SHIELD Project Website. Available online: https://www.heat-shield.eu (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- HEAT-SHIELD Occupational Warning System Website Platform. Available online: https://heatshield.zonalab.it (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Vitart, F.; Balsamo, G.; Buizza, R.; Ferranti, L.; Keeley, S.; Magnusson, L.; Molteni, F.; Weisheimer, A. Sub-Seasonal Predictions; ECMWF Technical Memoranda 738; ECMWF: Reading, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.ecmwf.int/sites/default/files/elibrary/2014/12943-sub-seasonal-predictions.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Panofsky, H.A.; Brier, G.W. Some Applications of Statistics to Meteorology; State University, College of Earth and Mineral Sciences: University Park, PA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rajczak, J.; Kotlarski, S.; Salzmann, N.; Schär, C. Robust climate scenarios for sites with sparse observations: A two-step bias correction approach. Int. J. Clim. 2016, 36, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajczak, J.; Kotlarski, S.; Schär, C. Does Quantile Mapping of Simulated Precipitation Correct for Biases in Transition Probabilities and Spell Lengths? J. Clim. 2016, 29, 1605–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déqué, M. Frequency of precipitation and temperature extremes over France in an anthropogenic scenario: Model results and statistical correction according to observed values. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2007, 57, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monhart, S.; Spirig, C.; Bhend, J.; Bogner, K.; Schär, C.; Liniger, M.A. Skill of subseasonal forecasts in Europe: Effect of bias correction and downscaling using surface observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 7999–8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Tank, A.M.G.; Wijngaard, J.B.; Können, G.P.; Böhm, R.; Demarée, G.; Gocheva, A.; Mileta, M.; Pashiardis, S.; Hejkrlik, L.; Kern-Hansen, C.; et al. Daily dataset of 20th-century surface air temperature and precipitation series for the European Climate Assessment. Int. J. Clim. 2002, 22, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SwissMetNet: The MeteoSwiss Reference Monitoring Network. Available online: https://www.meteoswiss.admin.ch/content/dam/meteoswiss/en/Mess-Prognosesysteme/Bodenstationen/doc/SwissMetNetTheMeteoSwissReferenceMonitoringNetwork.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Pogačar, T.; Casanueva, A.; Kozjek, K.; Ciuha, U.; Mekjavić, I.B.; Kajfež Bogataj, L.; Črepinšek, Z. The effect of hot days on occupational heat stress in the manufacturing industry: Implications for workers’ well-being and productivity. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 1251–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifroth, U.; Kothe, S.; Müller, R.; Trentmann, J.; Hollmann, R.; Fuchs, P.; Werscheck, M. Surface Radiation Data Set—Heliosat (SARAH), 2nd ed.; Satellite Application Facility on Climate Monitoring (CM SAF): Offenbach, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minard, D.; Belding, H.S.; Kingston, J.R. Prevention of heat casualties. JAMA 1957, 165, 1813–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7243. Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Assessment of Heat Stress Using the WBGT (Wet Bulb Globe Temperature) Index, 3rd ed.; ISO/TC 159/SC 5 Ergonomics of the Physical Environment; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NATO-HFM 187. Management of Heat and Cold Stress Guidance to NATO Medical Personnel; RTO TECHNICAL REPORT-TR-HFM-187; NATO Science and Technology Organisation: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; Available online: https://research.vu.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/1070715/NATO-HFM-187.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2019).

- American College of Sports Medicine; Armstrong, L.E.; Casa, D.J.; Millard-Stafford, M.; Moran, D.S.; Pyne, S.W.; Roberts, W.O. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exertional heat illness during training and competition. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racinais, S.; Alonso, J.M.; Coutts, A.J.; Flouris, A.D.; Girard, O.; González-Alonso, J.; Hausswirth, C.; Jay, O.; Lee, J.K.W.; Mitchell, N.; et al. Consensus recommendations on training and competing in the heat. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrett, N.; Kingma, B.R.M.; Sluijter, R.; Daanen, H.A.M. Ambient Conditions Prior to Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Considerations for Acclimation or Acclimatization Strategies. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, B.; Kjellstrom, T. Calculating workplace WBGT from meteorological data: A tool for climate change assessment. Ind. Health 2012, 50, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parson, K.C. Human Thermal Environment: The Effects of Hot, Moderate and Cold Temperatures on Human Health, Comfort and Performance, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi, H.; Wijayanto, T.; Lee, J.Y.; Hashiguchi, N.; Saat, M.; Tochihara, Y. Comparison of heat dissipation response between Malaysian and Japanese males during exercise in humid heat stress. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2011, 55, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, T.E.; Pourmoghani, M. Prediction of workplace wet bulb global temperature. Appl. Occup. Envrion. Hyg. 1999, 14, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljegren, J.C.; Carhart, R.; Lawday, P.; Tschopp, S.; Sharp, R. Modeling wet bulb globe temperature using standard meteorological measurements. J. Occup. Envrion. Hyg. 2008, 5, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanueva, A. R Package “HeatStress”. Zenodo. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3264930 (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Buizza, R.; Leutbecher, M. The forecast skill horizon. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 141, 3366–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, D.; Du Bois, E.F. Clinical calorimetry: Tenth paper a formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Arch. Intern. Med. 1916, 17, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouno, T.; Katsumata, N.; Mukai, H.; Ando, M.; Watanabe, T. Standardization of the body surface area (BSA) formula to calculate the dose of anticancer agents in Japan. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 33, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlarski, G.; Palkowski, A.; Krawczuk, M. Body surface area formulae: An alarming ambiguity. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.A. Body Surface Area in Dosing Anticancer Agents: Scratch the Surface! J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002, 94, 1822–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, A.D.; Drinkwater, D.T.; Clarys, J.P. Human body surface area: Validation of formulae based on cadaver study. Hum. Biol. 1984, 56, 475–488. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Moss, J.; Thisted, R. Predictors of body surface area. J. Clin. Anesthesia 1992, 4, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, H. Determination of Body Surface Area and Formulas to Estimate Body Surface Area Using the Alginate Method. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2008, 27, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ISO 8996. Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Determination of Metabolic Rate, 2nd ed.; ISO/TC 159/SC 5 Ergonomics of the Physical Environment; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Zhu, N.; Zheng, G.; Wei, H. Experimental study on physiological and psychological effects of heat acclimatization in extreme hot environments. Build. Envrion. 2011, 46, 2033–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, T.; Min, Y.; Yang, H. Seasonal acclimatization to the hot summer over 60 days in the Republic of Korea suppresses sweating sensitivity during passive heating. J. Biol. 2013, 38, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH). TLVs and BEIs. Threshold Limit Values for Chemical Substances and Physical Agents and Biological Exposure Indices; American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, Y.; Moran, D.; Epstein, Y. Acclimatization strategies—Preparing for exercise in the heat. Int. J. Sports Med. 1998, 19 (Suppl. 2), S161–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.A. Human heat adaptation. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 325–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, T.M.; Ramadan, M.Z.; Al-Ashaikh, R.A. How many days are required for workers to acclimatize to heat? Work 2017, 56, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanas, R.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Bhend, J.; Hemri, S.; Doblas-Reyes, F.J.; Torralba, V.; Penabad, E.; Brookshaw, A. Bias adjustment and ensemble recalibration methods for seasonal forecasting: A comprehensive intercomparison using the C3S dataset. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 53, 1287–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.S. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK; Waltham, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 100. [Google Scholar]

- Arcury, T.A.; Estrada, J.M.; Quandt, S.A. Overcoming language and literacy barriers in safety and health training of agricultural workers. J. Agromed. 2010, 15, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messeri, A.; Morabito, M.; Bonafede, M.; Bugani, M.; Levi, M.; Baldasseroni, A.; Binazzi, A.; Gozzini, B.; Orlandini, S.; Nybo, L.; et al. Heat Stress Perception among Native and Migrant Workers in Italian Industries—Case Studies from the Construction and Agricultural Sectors. Int. J. Envrion. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keatinge, W.R.; Donaldson, G.C.; Cordioli, E.; Martinelli, M.; Kunst, A.E.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Nayha, S.; Vuori, I. Heat related mortality in warm and cold regions of Europe: Observational study. BMJ 2000, 321, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez, C.; Ballester, F.; Ferrandiz, J.; Pérez-Hoyos, S.; Sáez, M.; López, A.; TEMPRO-EMECAS. Relation between temperature and mortality in thirteen Spanish cities. Int. J. Envrion. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 3196–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Li, S.; Guo, Y.; Han, X.; Jaakkola, J.J.K. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between daily mean temperature and mortality in China. Envrion. Res. 2019, 173, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafei, D.; Bolbol, S.A.; Awad Allah, M.B.; Abdelsalam, A.E. Exertional heat illness: Knowledge and behavior among construction workers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 32269–32276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Garbarino, S.; Bragazzi, N.L. Migrant Workers from the Eastern-Mediterranean Region and Occupational Injries: A Retrospective Database-Based Analysis from North-Eastern Italy. Int. J. Envrion. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Smith, J.B.; Burton, I. Integration of Public Health with Adaptation to Climate Change: Lesson Learned and New Directions, 1st ed.; CRC Press; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kjellstrom, T.; Holmer, I.; Lemke, B. Workplace heat stress, health and productivity—An increasing challenge for low and middle income countries during climate change. Glob. Health Act. 2009, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellstrom, T.; Lemke, B.; Otto, M. Climate conditions, workplace heat and occupational health in South-East Asia in the context of climate change. WHO South East Asia J. Public Health 2017, 6, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, M.; Crisci, A.; Messeri, A.; Messeri, G.; Betti, G.; Orlandini, S.; Raschi, A.; Maracchi, G. Increasing Heatwave Hazards in the Southeastern European Union Capitals. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellstrom, T.; Freyberg, C.; Lemke, B.; Otto, M.; Briggs, D. Estimating population heat exposure and impacts on working people in conjunction with climate change. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSHA-NIOSH Heat Safety Tool App. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/heatstress/heatapp.html (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- ClimApp. Available online: http://www.lth.se/climapp (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Morabito, M.; Messeri, A.; Orlandini, S.; Kjellstrom, T.; Flouris, A.D. HEAT-SHIELD tools for short-term warnings and long-term planning: Heat-stress protection strategies to reduce the impact on different working environments and activities. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on the Physiology and Pharmacology of Temperature Regulation (PPTR), Split, Croatia, 7–12 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou, L.G.; Tsoutsoubi, L.; Samoutis, G.; Bogataj, L.K.; Kenny, G.P.; Nybo, L.; Kjellstrom, T.; Flouris, A.D. Time-motion analysis as a novel approach for evaluating the impact of environmental heat exposure on labor loss in agriculture workers. Temperature 2017, 4, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masanotti, G.; Bartalini, M.; Fattorini, A.; Cerrano, A.; Messeri, A.; Morabito, M.; Iacopini, S. Work in Harsh Hot Environment: Risk Evaluation on Thermal Stress in a Farm during Green Pruning Activity. BJSTR 2019, 16, 12103–12111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogacar, T.; Znidarsic, Z.; Kajfez Bogataj, L.; Flouris, A.D.; Poulianiti, K.; Crepinsek, Z. HeatWaves Occurrence and Outdoor Workers’ Self-assessment of Heat Stress in Slovenia and Greece. Int. J. Envrion. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhong, S.; Morabito, M.; Hajat, S.; Xu, Z.; He, Y.; Bao, J.; Sheng, R.; Li, C.; Fu, C.; et al. Estimation of work-related injury and economic burden attributable to heat stress in Guangzhou, China. Sci. Total Envrion. 2019, 666, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Kuklane, K.; Östergren, P.O.; Kjellstrom, T. Occupational heat stress assessment and protective strategies in the context of climate change. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bouwarthan, M.; Quinn, M.M.; Kriebel, D.; Wegman, D.H. Assessment of Heat Stress Exposure among Construction Workers in the Hot Desert Climate of Saudi Arabia. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2019, 63, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, M.; Profili, F.; Crisci, A.; Francesconi, P.; Gensini, G.F.; Orlandini, S. Heat-related mortality in the Florentine area (Italy) before and after the exceptional 2003 heat wave in Europe: An improved public health response? Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrgou, A.; Santamouris, M. Increasing Probability of Heat-Related Mortality in a Mediterranean City Due to Urban Warming. Int. J. Envrion. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xu, Z.; Bambrick, H.; Su, H.; Tong, S.; Hu, W. Heatwave and elderly mortality: An evaluation of death burden and health costs considering short-term mortality displacement. Envrion. Int. 2018, 115, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HEAT-SHIELD Platform Risk Levels and Color Codes | WBGT Levels | Work Breaks | Water Consumption (Hydration) | HEAT-SHIELD Recommendations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unacclimatized | Acclimatized | ||||

| Not significant RL ≤ 80% | <22.5 LMR <20.0 MMR <18.5 HMR <17.5 VHMR | <25.0 LMR <23.0 MMR <21.5 HMR <20.5 VHMR |  |  LMR  from MMR to VHMR | No special precautions are required: Maintain normal working and hydration procedures. |

| Low 80% < RL < 100% | 22.5 LMR 20.0 MMR 18.5 HMR 17.5 VHMR | 25.0 LMR 23.0 MMR 21.5 HMR 20.5 VHMR |  |  LMR and MMR  HMR and VHMR | Pre-alarm (attention): Pay attention to frequent drinking and plan small breaks. |

| Moderate 100% ≤ RL < 120% | 28.5 LMR 25.0 MMR 23.0 HMR 22.0 VHMR | 31.0 LMR 28.5 MMR 27.0 HMR 25.5 VHMR |  |  LMR and MMR  HMR and VHMR | Alarm: Drink frequently and increase the number of breaks with cooling. |

| High RL ≥ 120% | >33.5 LMR >29.5 MMR >27.5 HMR >25.5 VHMR | >36.5 LMR >33.5 MMR >31.5 HMR >30.5 VHMR |  |  LMR and MMR  HMR and VHMR | Emergency: Drink often, even more than 1 L/h and schedule frequent breaks in shadowed or cool area. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morabito, M.; Messeri, A.; Noti, P.; Casanueva, A.; Crisci, A.; Kotlarski, S.; Orlandini, S.; Schwierz, C.; Spirig, C.; Kingma, B.R.M.; et al. An Occupational Heat–Health Warning System for Europe: The HEAT-SHIELD Platform. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162890

Morabito M, Messeri A, Noti P, Casanueva A, Crisci A, Kotlarski S, Orlandini S, Schwierz C, Spirig C, Kingma BRM, et al. An Occupational Heat–Health Warning System for Europe: The HEAT-SHIELD Platform. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(16):2890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162890

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorabito, Marco, Alessandro Messeri, Pascal Noti, Ana Casanueva, Alfonso Crisci, Sven Kotlarski, Simone Orlandini, Cornelia Schwierz, Christoph Spirig, Boris R.M. Kingma, and et al. 2019. "An Occupational Heat–Health Warning System for Europe: The HEAT-SHIELD Platform" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 16: 2890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162890

APA StyleMorabito, M., Messeri, A., Noti, P., Casanueva, A., Crisci, A., Kotlarski, S., Orlandini, S., Schwierz, C., Spirig, C., Kingma, B. R. M., Flouris, A. D., & Nybo, L. (2019). An Occupational Heat–Health Warning System for Europe: The HEAT-SHIELD Platform. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(16), 2890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162890