Abstract

Meeting adherence is an important element of compliance in treatment programmes. It is influenced by several factors one being self-efficacy. We aimed to investigate the association between self-efficacy and meeting adherence and other factors of importance for adherence among patients with alcohol and drug addiction who were undergoing an intensive lifestyle intervention. The intervention consisted of a 6-week Very Integrated Programme. High meeting adherence was defined as >75% participation. The association between self-efficacy and meeting adherence were analysed. The qualitative analyses identified themes important for the patients and were performed as text condensation. High self-efficacy was associated with high meeting adherence (ρ = 0.24, p = 0.03). In the multivariate analyses two variables were significant: avoid complications (OR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.29–0.90) and self-efficacy (OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.00–1.63). Reflections on lifestyle change resulted in the themes of Health and Wellbeing, Personal Economy, Acceptance of Change, and Emotions Related to Lifestyle Change. A higher level of self-efficacy was positively associated with meeting adherence. Patients score high on avoiding complications but then adherence to the intervention drops. There was no difference in the reflections on lifestyle change between the group with high adherence and the group with low adherence.

1. Introduction

Patients with alcohol and drug addiction often have additional risky lifestyle behaviours, e.g., smoking, poor nutrition and physical inactivity, as well as comorbidity; all these have a social gradient and add to the already high substance-induced morbidity and pre-mortality [1,2,3]. Effective health promotion aiming at those factors is therefore relevant to offer to this disadvantaged patient group as an integrated part of addiction treatment. However, lifestyle change is a complex process influenced by many factors related to the programme, the therapist and the individual person.

To meet the multiple needs related to lifestyle change among patients with alcohol and drug addiction, the individually tailored Very Integrated Program (VIP) has been translated from the 6-week intensive Danish Gold Standard Programme (GSP) on smoking cessation intervention with an approximately 30% continuous quit rate [4,5,6] for alcohol intervention, nutritional intervention, physical activity or combinations of these [7].

The intervention employs an Operational Model to facilitate successful lifestyle change, which incorporates the theories of Motivational Interviewing [8], Decisional Balance and the Trans-Theoretical Model of Change [9], all of which are related to the process of behavioural change [10]. A Cochrane review suggest that using only one theoretical approach may be insufficient for patients who are attempting lifestyle changes in relation to clinical treatment and argues that an intervention should include both measures to increase motivation, intensive behavioural support as well as nicotine replacement therapy in the case of smoking cessation to get the best results [11].

The prediction of a successful lifestyle intervention can have a major impact even for patients with substance use and severe mental diseases [12]. Among other issues the meeting adherence has been reported to be a strong predictor for successful outcomes [4,13,14,15]. Nevertheless, the factors associated with meeting adherence have been less investigated. The level of motivation and self-efficacy tend to be relevant and have been reported to be an important factor for prompting engagement into the process of change [8,9,16]. Although the self-efficacy itself is found not to be a robust predictor among patients with alcohol addiction [17].

According to Albert Bandura self-efficacy is defined as a person’s confidence in his or her intrinsic ability to accomplish goals [18] and is often measured by a visual analogue scale or a Likert scale similar to the one widely implemented for pain measurement. Central to the theory of self-efficacy are the person’s own expectations of efficacy, which determine the initiation of a coping behaviour, how much effort he or she will put into it, and for how long the effort will be sustained when confronted with barriers and obstructions. Reflections on the advantages and disadvantages of changing [19] may also be of importance for meeting adherence, and individuals with high meeting adherence might hypothetically have different reflections than those with low meeting adherence.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the possible association between the patients’ self-assessment of importance of avoiding complications, importance of changing lifestyle and their level of self-efficacy and adherence to the VIP intervention among patients undergoing treatment for alcohol and drug addiction. The secondary aims were to identify other possible factors of importance for meeting adherence.

2. Materials and Methods

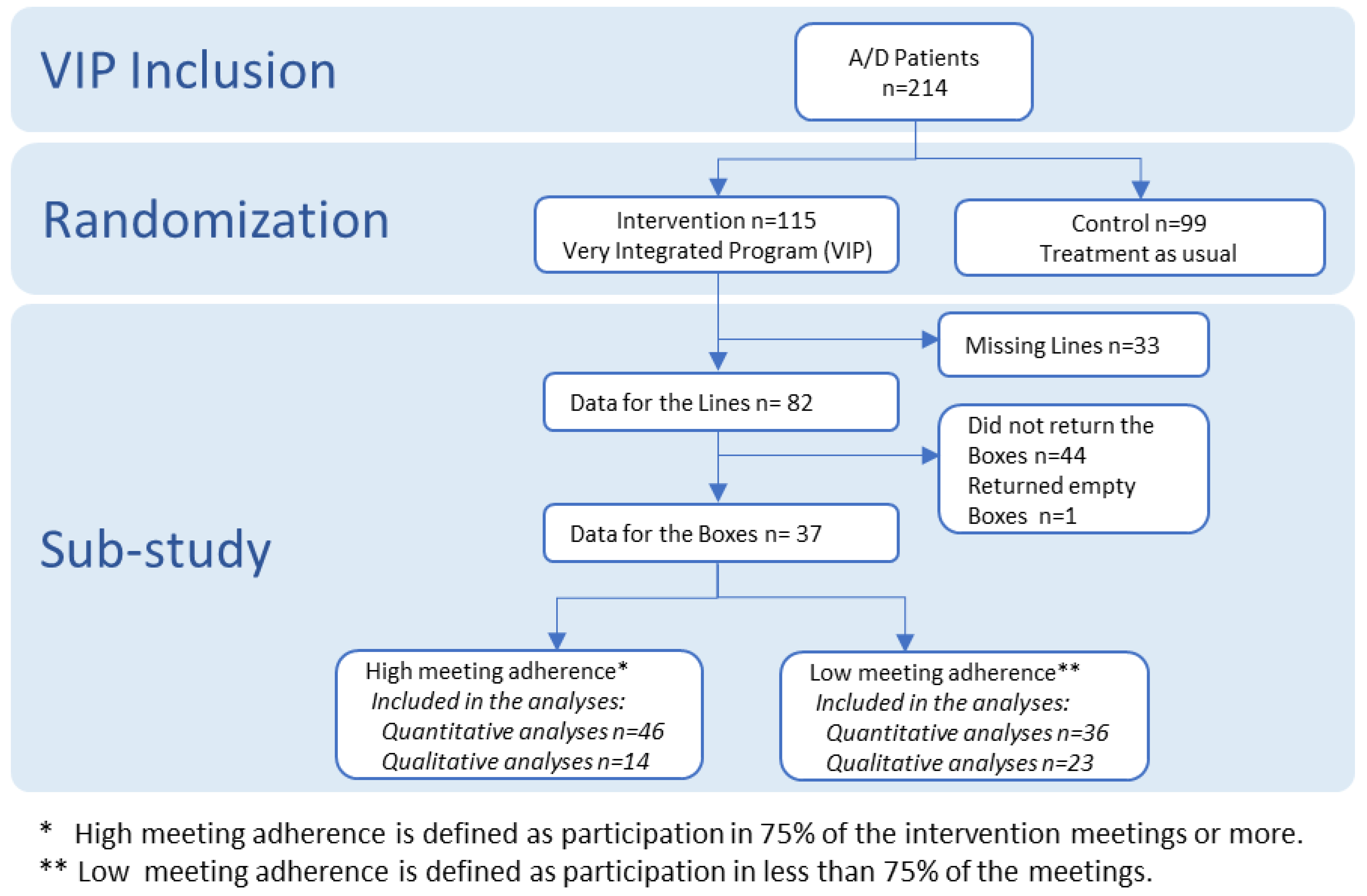

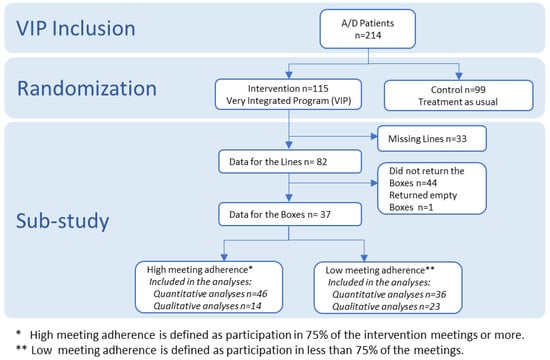

This study is a sub-study of a randomised controlled trial which will be reported at a later stage. This study includes the patients in the intervention group of the randomised study. The RCT was a clinical trial called VIP that took place in two addiction centres in Malmö, Sweden (Figure 1). The aim of the VIP-Study was to assess the effect of adding health promotion activities to treatment of alcohol and drug addiction. Results on the effect of the intervention are planned to be reported at a later stage [20]. The eligible participants were persons aged 18 or over and diagnosed with alcohol or drug addiction according to the ICD-10 criteria by the specialists at the Addiction Centre Malmö (4 units) and the Integrated Community Care Centre (one unit), Psychiatry Skåne, Sweden. The inclusion criteria for VIP was alcohol and drug addiction in accordance to ICD-10 criteria among patients who also had at least one risky lifestyle behaviour (daily smoking, daily physical activity less than 30 min, overweight and risk of malnutrition) and at least one comorbidity (diabetes, cardiovascular, respiratory and liver diseases). In VIP 115 patients were allocated to the intervention group. This present sub-study includes a total of 82 patients with alcohol or drug addiction who had completed The Line Tool for the quantitative study and 37 who completed The Box Tool were included in the qualitative study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Profile. VIP: Very Integrated Program.

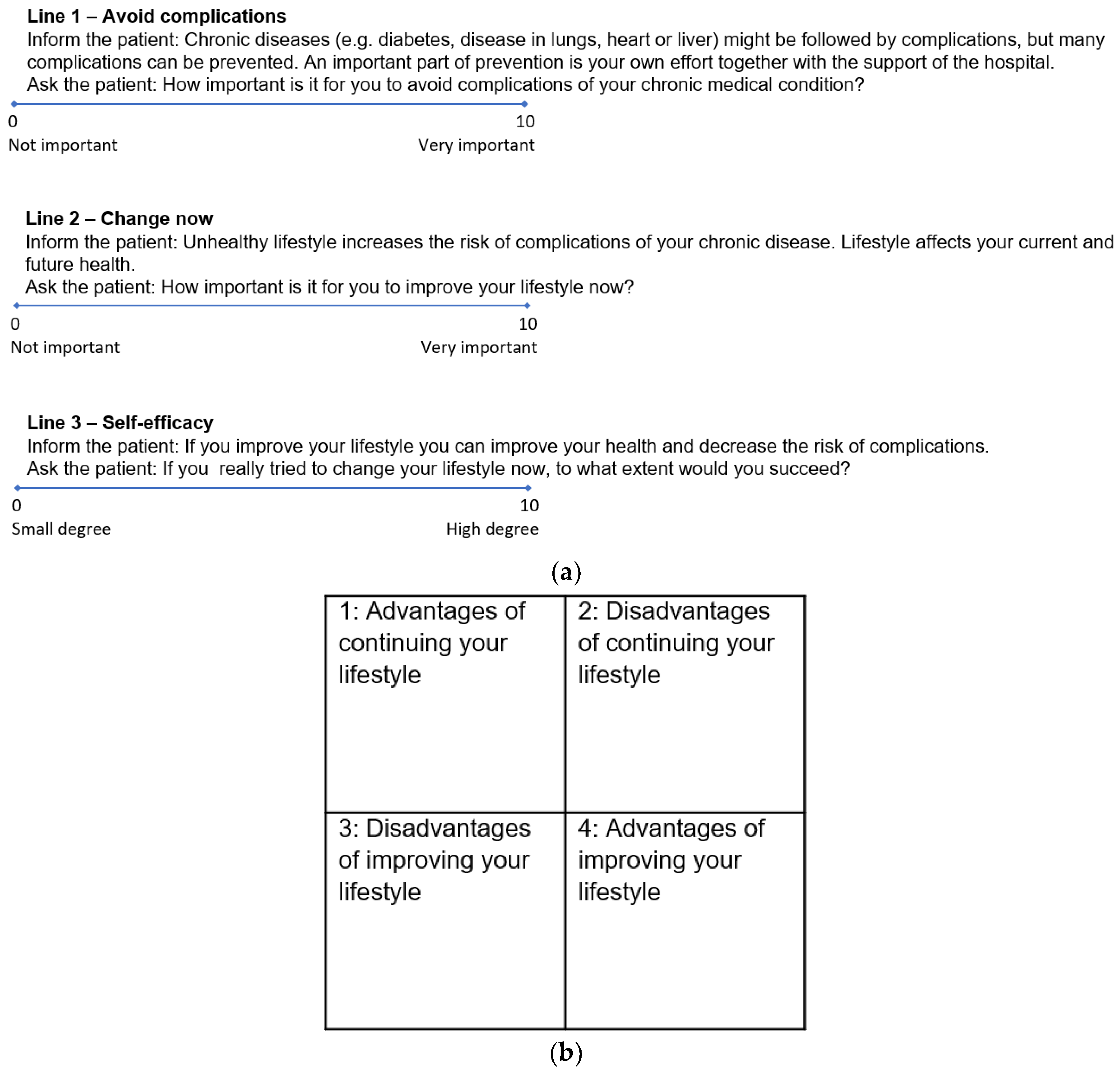

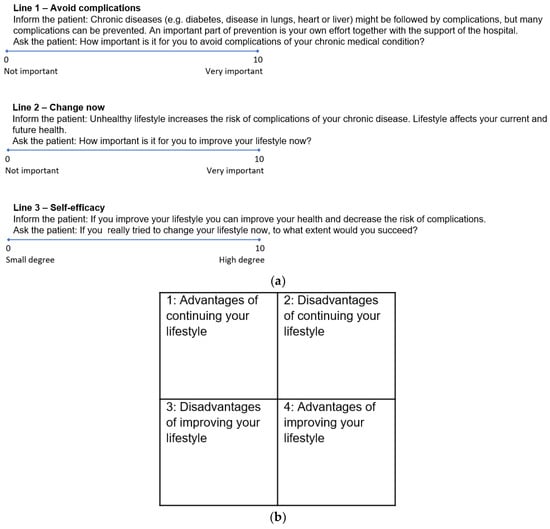

After obtaining informed consent, the VIP intervention group filled in The Line Tool as visual analogue scales [21] (Figure 2a). The lines are known from the motivational interviewing technique, where they have been validated [8]. The scale exists both in a version from 1–10 cm and a version from 0–10 cm. In this study we used the version from 0–10 which is similar to the visual analogue scales which is used in the clinical setting worldwide. The patients also structured their reflections as 1–4 in The Box Tool (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) The Line Tool (0–10 cm) [10], (b) The Box Tool (part 1–4) [10].

The VIP intervention was based on the Operational Model and translated from the GSP intervention. GSP includes motivational dialogues, an educational programme with five sessions aimed at risky lifestyle behaviours and an interactive workshop on comorbidity directed at patients and relatives. This programme involves six face-to-face meetings with a trained counsellor, each one being approximately an hour in duration. The Line Tool used in this model made it possible to rank the patients’ self-efficacy in achieving the change amongst others, while The Box Tool, besides assessing the advantages and disadvantages of the change, allowed patients to reflect upon the presence of ambivalence towards the change [10]. The patients kept the forms throughout the intervention as a reminder of their reflections. In this way we integrated qualitative research methods in the larger context of the clinical trial. It is argued in the developing debate on process evaluation that this is fruitful because empirical data add to the understanding of how an intervention is experienced by the participants, and how participants interact with the intervention under the influence of other factors such as circumstances, attitudes, beliefs, social norms and resources [22,23].

2.1. Data Collection

2.1.1. Quantitative Data

We collected the following information at inclusion of patients in the VIP study: Age, duration of addiction, gender, socioeconomic and lifestyle factors, comorbidity, self-evaluated quality of life via the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) [24] (Table 1) and meeting adherence defined as attendance to the meetings. In total the intervention included five meetings over six weeks approximately of one-hour duration each. Meeting attendance was recorded by the clinician performing the intervention. Adherence was dichotomised into high (≥75%) and low attendance (<75%) of sessions as high adherence has been shown to triple quit rates [25]. The data for lines came from measures on the VAS scale 0–10 cm (Figure 2a). SF-36 is used to measure the self-reported quality of life [24]. The questions in SF-36 are focused around two main domains, the physical and mental health [24]. For example, the first item reads “In general, would you say your health is…” with the scoring options “Excellent, Very good, Good, Fair, Poor”, and item nine a reads “These questions are about how you feel and how things have been with you during the past month. How much time during the past month: Did you feel full of life?” having the answering options “All of the time, Most of the time, A good bit of the time, Some of the time, A little of the time, None of the time” [24].

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

The reliability and validity of the survey has been tested among many patient populations including patients with alcohol and drug addiction [26,27]. They reported Cronbach’s Alpha ≥ 0.7. In a Swedish context it has also proven a high reliability with a Cronbach’s Alpha ≥ 0.8. [28].

2.1.2. Qualitative Data

The qualitative data consisted of the patients’ reflections on advantages and disadvantages regarding lifestyle intervention as described above in the Box Tool (Figure 2b).

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Quantitative Analyses

First, we used the Spearman’s correlation test (ρ) to examine the association between The Line Tool components measuring the patients’ perceived importance of the following categories: avoid complications (Line 1), immediate change (Line 2) and self-efficacy (Line 3) and meeting adherence.

To analyse differences between the groups with high- and low attendance, we conducted univariate analyses and used the Chi-square test for the dichotomous variables and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. The significance level was set at 0.05, two-sided. All the predictive variables such us Complications, Change, Self-efficacy, Age, Years of addiction and Sex were entered together into the multivariable logistic regression analysis for identifying factors of significance using odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

For quantitative analyses we used the IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 22 [29].

2.2.2. Qualitative Analyses—Systematic Text Condensation

The handwritten answers of the patients in The Box Tool were converted to the digital form of an Excel sheet and imported into NVivo qualitative data analysis software, version 11 [30] for coding. Some of the answers had no direct relation to the questions and were therefore excluded from the analyses.

The data was analysed using Kirsti Malterud’s approach of systematic text condensation [31]. Systematic text condensation consists of 4 steps: Total impression of all answers and identifying preliminary themes, Coding by identifying and sorting meaning units, Condensation into code groups and Synthesising the condensates into a story grounded in the empirical data.

KH and RR independently read the patient reflections thoroughly to get a total impression and to identify preliminary themes. These themes were largely identical such as “Health” and “Economy”, but there were also some discrepancies. For example, the preliminary theme of “Social life/family” was only identified by one of the coders and some themes such as “Weight” and “More alert” were included in the overall theme of “Health”. Subsequently, the data was systematically reviewed for meaning units, which gave rise to codes that were then separated into thematic groups and a condensate was developed. This was done by RR and then the thematic groups and sub-groups were discussed by KH and RR until consensus was reached. The condensates were then synthesised, and descriptions and concepts were developed by RR to clarify the study question. Since the research objective was to identify important factors for adherence, the data were sorted in high and low adherence and analysed accordingly. The two analyses were then checked for divergent themes.

2.3. Comprehensiveness of the Available Data

2.3.1. Quantitative Data: Sample Size Estimation

The number was calculated using: n = (Z2α + Zβ)2 × (P1(1 − P1) + P2(1 − P2))/(P1 − P2)2, where 2α = 5% => Z2α = 1.96 and 1 − β = 80% => β = 20% => Zβ = 0.84. P1 = 75% and P2 = 45% => n = 38 in each group of high and low attendance [32]. P2 = 45% (the lowest estimate for attendance). P1 = 75% (the highest estimate for attendance).

2.3.2. Qualitative Data: Data Saturation

In qualitative research, the indication of when to stop collecting data is the methodological principle of data saturation; as data is being collected, patterns and themes will emerge and begin to reproduce themselves. When this happens, it is estimated that no further data is needed because the data is “saturated” [33]. In traditional qualitative interview studies, data saturation is expected to be reached after approximately 12 interviews [34]. In our case data was collected from all 37 patients and as expected several major themes were identified in the data.

2.4. Ethical Issues

The VIP study has been approved by the Ethical Review Board (Dnr2010/470) in accordance with the Swedish Data Protection Agency and the protocol was registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01414907). The patients were included after informed consent.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data

We found that only self-efficacy (Line 3) was positively associated with meeting adherence, ρ = 0.24, p = 0.03 which was significant. The patients’ perceptions of importance for changing lifestyle immediately (Line 2) and avoiding complications (Line 1) was not found to be statistically significant.

In the univariate analyses the only significant difference between the two groups with high and low adherence were the perception of self-efficacy, which remained significant in the multivariate analyses (OR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.01–1.51). The importance of avoiding complications, although not significant in the univariate analyses, became significant in the multivariable model (OR: 0.51; 95% CI: 0.29–0.90) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the characteristics of the groups with high and low meeting attendance.

3.2. Qualitative Data

We identified 4 major themes and 11 sub-themes (Table 3). There were no substantial differences between the answers of the group with high adherence and the group with low adherence. The same themes and sub-themes were present, and only the subtheme of “Continuing current lifestyle restrains individuals in poor economy” was referred to a little less frequently in the group with high adherence.

Table 3.

Reflections on advantages and disadvantages of lifestyle change.

Considering the major themes and sub-themes identified through the analysis, there were evident patterns in patient reflections. These patterns drew a common picture of patients, of whom many were very aware of how their lifestyle influenced their health and wellbeing.

They saw improving lifestyle as an advantage because it would improve their health and they were aware that if they continued their current lifestyle it would not only cause poor health and future health risks but possibly also a premature death.

It was also evident for the patients that lifestyle change would have an impact on their personal economy. They expected to be restrained in poor economy if they continued their current lifestyle and to improve their personal economy if they improved their lifestyle.

The patients expressed a strong acceptance of change finding no advantages of continuing their current lifestyle and finding no disadvantages of improving their current lifestyle.

Finally, it became clear that the patients related strong emotions to lifestyle change. They found that maintaining status quo was easier than changing routine. They also found positive social implications of lifestyle improvement and especially emphasised improved contact with their children. They associated their current lifestyle with positive emotions and expected lifestyle improvement to cause negative emotions.

4. Discussion

We found that meeting adherence during the 6-week VIP intervention was positively associated with a high pre-intervention score for self-efficacy. This is similar to results of another study that found that positive expectations had improved effect on treatment retention [35] but on the other side, an older review found that changes in the self-efficacy and the benefit from self-efficacy on outcome was heterogeneous [36]. We also identified several themes in the patients’ reflections on the advantages and disadvantages of lifestyle change: Health and Well-being, Personal Economy, Acceptance of Change, and Emotions Related to Lifestyle Change. These themes were identical in the groups with high and low adherence.

It is a surprising result, that patients score high on avoiding complications (Line 1), but then their adherence to the intervention drop, although this result was not significant.

The positive correlation between the patients’ expectations of their own efficacy and the duration they adhered to the intervention is in line with Bandura’s theory [18], but despite the wide discussion of self-efficacy in the literature, we found no other studies about self-efficacy and integrated health promotion intervention on patients with alcohol and drug addiction. However, our results are to some degree supported by other studies. A previous review about the effect of self-efficacy on various health care interventions concluded that self-efficacy is a powerful predictor for better intervention outcomes, especially regarding smoking secession and, to some extent, physical activity and weight control [37]. A more recent study found that high confidence (equivalent to self-efficacy, Line 3) was associated with a positive outcome regarding both drinking and smoking [38] while another study associated the low self-efficacy with a relapse among drug users [39]. On the other side, an older study found that the lower score of self-efficacy at the baseline was associated with higher rates of abstinence after 6 months among the patients with alcohol addiction, but the same group of patients had two-fold increase in self-efficacy score during this period [40] this was also supported by another study [41]. Nevertheless, a study by Romero et al. reported the intermediate self-efficacy score to be associated with the better outcomes among the patients with the drug addiction, whereas the low and high scores predicted a inferiors results [42].

Other studies have reported contradictory results on participant adherence to a 12-week physical activity programme. However, many other factors, such as health literacy and numeracy, may also impact self-reporting [43], but no clear cut-offs, mediators and moderators for the effect of health literacy have been determined for clinical use [44].

4.1. Methodological Implications

Qualitative methods can help us understand the clinical context of complex interventions and identify unexpected mechanisms [45]. In this study the qualitative answers shed more light on the results obtained from the quantitative measures. For example, the patients’ responses that they find avoiding complications very important is unfolded in their descriptions of which complications they are afraid to experience and what consequences it will have for their life. However, on this background it is unexpected to observe, that they less frequently come to the meetings.

The way patients interact with the intervention is influenced by their circumstances, attitudes, beliefs, social norms and resources [22,23]. It is interesting that both the group with high and the group with low meeting adherence are aware that continuing their current lifestyle might cause poor health and future health risks including possible premature death and improving their lifestyle will improve their health. A high awareness of these issues does not seem to influence the motivation to attend the meetings of the intervention since assessing it as important to avoid complications of comorbidity on the line scale is associated with lower meeting adherence.

In many ways these results capture the complexity of patient reflections as they stand on the brink of lifestyle change. Advantages and disadvantages coexist. For example, there seems to be an acceptance of change, because when asked, the patients see no advantages of continuing their unhealthy lifestyle and no disadvantages of improving their lifestyle. The patients point to health and wellbeing as major advantages of changing lifestyle and they expect their personal economy to improve. At the same they express strong emotions of barriers to lifestyle change. The routines of their current lifestyle have a strong hold of them, they associate positive emotions to their current lifestyle and expect that changing lifestyle will cause negative emotions. These factors might contribute to an explanation of why an intervention might (not) work, for whom, and under what circumstances [45].

These major themes from the reflections of Health and Wellbeing, Personal Economy, Acceptance of Change, and Emotions Related to Lifestyle Change may also be of importance for the general support and facilitation of the changing process among this group of patients with alcohol and drug addiction. The clear messages on personal economy and the high acceptance of change seem easy to include and revisit to drive support for the patients’ process of change.

4.2. Clinical Implications

A special focus should be put on how positive emotions such as inner calm and anxiety relief are experienced as an advantage of current lifestyle with addiction and that negative emotions are expected to be a disadvantage of changing this lifestyle. Additionally, the expression of emotions related to changing of lifestyle should be an important element for the staff supporting the change; they should acknowledge both that staying with the status quo is easier than changing routine and that the current lifestyle is associated with the positive emotions while improving lifestyle is expected to cause negative emotions. While acknowledging the expectations of the patients, intervention staff should also rely on evidence in the area.

4.3. Research Implications

In addition to co-morbidity the VIP-programme intervenes on the four risk factors of smoking, physical inactivity, overweight and malnutrition. Evidence on the association between risk reduction and positive emotional and mental state already exist in several areas.

Interestingly, a systematic review with meta-analyses from 2014 shows that smoking cessation is associated with reduced depression, anxiety and stress after the period of withdrawal symptoms [46]. Therefore, issues of smoking cessation for patients with a psychiatric diagnosis should not be avoided [47], but on the contrary, encouraged [12].

A review from 2019 shows how exercise has positive effects on brain health including decreased risks of depression and stress in of patients with neurological and mental illnesses [48]. In the general population, physical activity also has a positive effect on anxiety [48] and the evidence is still growing for a general positive effect of physical activity on mental health [49].

We have not been able to identify reviews on the influence of improved nutrition on well-being in this patient group, and this knowledge gap needs to be investigated in future research.

In the VIP-study, the recruited patients were already in treatment for alcohol and drug abuse, and therefore these risk factors were not included in the VIP-programme. However, a trial by Berman et al. shows that participants with a problematic alcohol intake who reduce this intake reported better wellbeing including lower stress, better social life satisfaction and lower rated of depressed mood at 12 months follow up. There was no difference in the group of drug users [50].

4.4. Suggestions for Future Research

The results of this study can generate hypotheses for future studies and suggest explanations that can inform future interventions [22] where such hypotheses can be tested. It would be clinically relevant to investigate if seeking to obtain a possible outcome triggers lifestyle change more than seeking to avoid a negative outcome. For example, if seeking to obtain improved health triggers lifestyle change more than seeking to avoid a premature death.

The time perspective is another clinically relevant area for investigation. Studies have shown that patients are motivated to quit drinking in the perioperative period to avoid postoperative complications such as cardiopulmonary complications, bleeding episodes and infections [51]. Our results indicate, that the patients in this study are not motivated to change lifestyle by reducing their risk of complications to their chronic medical condition. To optimise lifestyle intervention, it would be relevant to investigate if decision making of lifestyle change is associated with the expected time perspective (short term or long term) of the benefit of the change.

To summarise we could assume that the surprising quantitative findings reflects the patients’ coexistence of positive and negative expectations to lifestyle change. The patients are concerned about complications, but at the same time they do not have the resources handle the expected negative emotions that come with the change and therefore they do not come to the meetings. On the other hand, the ones who rate themselves high on self-efficacy manage to set aside the expected negative emotions and focus on the expected positive outcomes of improved health and economy and therefore come to the meetings to continue their lifestyle change.

4.5. Lessons Learned

(1) There is a discrepancy between what patients say and know about the importance of avoiding complications and what they do to avoid them when it comes to adhere to an intervention programme.

(2) Patients have negative expectations towards the emotional side of lifestyle change, though there is evidence for the contrary.

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

Among the strengths of this study was the general homogeneity of the included patients who furthermore also received the same VIP intervention irrespective of their self-efficacy score.

Even though 33 (29%) of the patients from the original VIP study were not included in this sub-study due to missing data, the power estimate illustrated that the 82 included patients were sufficient for the quantitative analyses. In the same manner, the analyses for data saturation confirmed that the data from the 37 completed boxes would be sufficient for including into the qualitative analyses.

The box was easy to complete and did not require extensive involvement from the staff. On the other hand, it prompted shorter answers which could be challenging for in depth data extraction. When filling in the box, the patient was supposed to begin with the question “Advantages of the current lifestyle” and finish with answering the question “Advantages of changing”. It was supposed to structure the considerations and ambivalence related to the process towards improving lifestyle change [10]. This could also predispose the patients to answer in a certain way. However, since the project staff did not interfere with completing the boxes this possible bias was considered low.

The two statistically significant variables from the quantitative analyses were avoiding complications and self-efficacy. The risk of a type I error could be reduced by repeating the study. On the other hand, the non-significant results of other variables could be attributed to the type II error and may have reached a significant level if the study population was even larger.

The study only included patients from addiction treatment organisations in Malmö, Skåne region, which might have different demographics compared not only with other countries but also with other regions within Sweden. This implies that a similar study conducted in a different location might garner different findings.

In this study meeting adherence was defined in relation to the 6-week intervention. Longer- or shorter-interventions could thus show different results.

5. Conclusions

We found that when patients score high on wanting to avoid complications, their meeting adherence drops, and a high level of self-efficacy was positively associated with high adherence to the intervention meetings among patients with alcohol and drug addiction. The negative association between avoiding complications and meeting adherence is surprising and should be further investigated in future studies. Recognising the self-efficacy as a predictive factor for better intervention compliance in this group should be accepted with precaution. There was no difference in the identified themes of pros and cons of the patients with high and low adherence. In general, the patients showed solid concerns about their health and wellbeing as well as their personal economy. They were ready for change, but also displayed strong emotions regarding the process of change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.T., K.H., J.A. and R.R; methodology, K.H., R.R., H.T. and J.A.; validation, K.H., R.R., H.T., J.A., M.G. and M.W.; formal analysis, K.H., R.R., H.T. and J.A.; investigation, K.H., R.R. and M.G.; data curation, K.H. and M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, K.H. and R.R.; writing—review and editing, H.T., J.A., M.G. and M.W.; visualisation, K.H. and R.R.; supervision, H.T. and J.A.; project administration, R.R.; funding acquisition, H.T.

Funding

This research was funded by Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research, grant number 2009-1663, the Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs, grant number 2013-0062, Stiftelsen Lindhaga and SUS stiftelser och donationer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Karin Dahlström for input to the analyses for this study and Mette Rasmussen for consulting on statistical methodology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Beynon, R.A.; Lang, S.; Schimansky, S.; Penfold, C.M.; Waylen, A.; Thomas, S.J.; Pawlita, M.; Waterboer, T.; Martin, R.M.; May, M.; et al. Tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking at diagnosis of head and neck cancer and all-cause mortality: Results from head and neck 5000, a prospective observational cohort of people with head and neck cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonevski, B.; Regan, T.; Paul, C.; Baker, A.L.; Bisquera, A. Associations between alcohol, smoking, socioeconomic status and comorbidities: Evidence from the 45 and Up Study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014, 33, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.; Rehm, J. When risk factors combine: The interaction between alcohol and smoking for aerodigestive cancer, coronary heart disease, and traffic and fire injury. Addict. Behav. 2006, 31, 1522–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.; Fernández, E.; Tønnesen, H. Effectiveness of the gold standard programme COMPARED with other smoking cessation interventions in Denmark: A cohort study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, T.; Rasmussen, M.; Heitmann, B.L.; Tønnesen, H. Gold standard program for heavy smokers in a real-life setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4186–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, T.; Villebro, N.; Møller, A.M. Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 27, CD002294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauridsen, S.V.; Thomsen, T.; Thind, P.; Tønnesen, H. STOP smoking and alcohol drinking before OPeration for bladder cancer (the STOP-OP study), perioperative smoking and alcohol cessation intervention in relation to radical cystectomy: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C.; Norcross, J.C. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 1102–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tønnesen, H. Engage in the Process of Change: Facts and Methods; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, T.; Villebro, N.; Moller, A.M. Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.; Klinge, M.; Krogh, J.; Nordentoft, M.; Tønnesen, H. Effectiveness of the Gold Standard Programme (GSP) for smoking cessation on smokers with and without a severe mental disorder: A Danish cohort study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, T.; Rasmussen, M.; Ghith, N.; Heitmann, B.L.; Tonnesen, H. The gold standard programme: Smoking cessation interventions for disadvantaged smokers are effective in a real-life setting. Tob. Control 2013, 22, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, E.; Hassmén, P.; Welvaert, M.; Pumpa, K.L. Behavioural treatment strategies improve adherence to lifestyle intervention programmes in adults with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Obes. 2017, 7, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.W.Y.; Chan, R.S.M.; Sea, M.M.M.; Woo, J. An overview of factors associated with adherence to lifestyle modification programs for weight management in adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Berre, A.P.; Rauchs, G.; la Joie, R.; Segobin, S.; Mézenge, F.; Boudehent, C.; Vabret, F.; Viader, F.; Eustache, F.; Pitel, A.L.; et al. Readiness to change and brain damage in patients with chronic alcoholism. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 213, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwaltney, C.J.; Metrik, J.; Kahler, C.W.; Shiffman, S. Self-efficacy and smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2009, 23, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, J.L.; Mann, L.M. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hovhannisyan, K.; Adami, J.; Wikström, M.M.; Tønnesen, H. Very integrated program (VIP): Smoking and other lifestyles, co-morbidity and quality of life in patients undertaking treatment for alcohol and drug addiction in Sweden. Clin. Health Promot. 2018, 8, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.H.S.; Patterson, D.G. Experimental development of the graphic rating method. Psychol. Bull. 1921, 18, 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.K.F.; Metcalfe, A. Qualitative methods and process evaluation in clinical trials context: Where to head to? Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Cooper, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; et al. Process evaluation in complex public health intervention studies: The need for guidance. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.; Kosinski, M.; Gandek, B. SF36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide; QualityMetric Incorporated: Lincoln, RI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ghith, N.; Ammari, A.; Rasmussen, M.; Frølich, A.; Cooper, K.; Tønnesen, H. Impact of compliance on quit rates in a smoking cessation intervention: Population study in Denmark. Clin. Health Promot. 2012, 2, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daeppen, J.B.; Krieg, M.A.; Burnand, B.; Yersin, B. MOS-SF-36 in evaluating health-related quality of life in alcohol-dependent patients. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 1998, 24, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, E.C.; Hsueh, I.P.; Hsieh, C.H.; Hsieh, C.L. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability, and construct validity of the SF-36 health survey in people who abuse heroin. J. Med. Assoc. 2014, 113, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, M.; Karlsson, J.; Ware, J.E., Jr. The Swedish SF-36 health Survey-I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- QSR. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, T.; Christensen, E.; Kampmann, J.P. Clinical Research Methods—A Basic Book; Munksgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Meth. 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusisto, K.; Knuuttila, V.; Saarnio, P. Clients’ self-efficacy and outcome expectations: Impact on retention and effectiveness in outpatient substance abuse treatment. Addict. Disord. Treat. 2011, 10, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcehimes, A.A.; Tonigan, J.S. Self-efficacy as a factor in abstinence from alcohol/other drug abuse: A meta-analysis. Alcohol. Treat. Q. 2008, 26, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strecher, V.J.; DeVellis, B.M.; Becker, M.H.; Rosenstock, I.M. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Educ. Q. 1986, 13, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertholet, N.; Gaume, J.; Faouzi, M.; Gmel, G.; Daeppen, J.B. Predictive value of readiness, importance, and confidence in ability to change drinking and smoking. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, Z.; Taghizadeh, F.; Bahramzad, O. Relationship between addiction relapse and self-efficacy rates in injection drug users referred to Maintenance Therapy Center of Sari, 1391. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2014, 6, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burling, T.A.; Reilly, P.M.; Moltzen, J.O.; Ziff, D.C. Self-efficacy and relapse among inpatient drug and alcohol abusers: A predictor of outcome. J. Stud. Alcohol 1989, 50, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentine, R.; Hillhouse, M.P. Self-efficacy, expectancies, and abstinence acceptance: Further evidence for the addicted-self model of cessation of alcohol- and drug-dependent behavior. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2000, 26, 497–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.C.; Pérez, E.J.P.; López, M.P. Coping self-efficacy against alcohol and other drugs use as treatment outcome predictor and its relation with personality dimensions: Evaluation of a sample of addicts using DTCQ, VIP and MCM-II. Adicciones 2007, 19, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Vassy, J.L.; O’Brien, K.E.; Waxler, J.L.; Park, E.R.; Delahanty, L.M.; Florez, J.C.; Meigs, J.B.; Grant, R.W. Impact of literacy and numeracy on motivation for behavior change after diabetes genetic risk testing. Med. Decis. Mak. 2012, 32, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Viera, A.; Crotty, K.; Holland, A.; Brasure, M.; Lohr, K.N.; Harden, E.; et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: An updated systematic review. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. 2011, 199, 941. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, P.; Huby, G.; Merriweather, J.; Salisbury, L.; Rattray, J.; Griffith, D.; Walsh, T.; On behalf of the RECOVER collaborators. Patient and carer experience of hospital-based rehabilitation from intensive care to hospital discharge: Mixed methods process evaluation of the RECOVER randomized clinical trial. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.; McNeill, A.; Girling, A.; Farley, A.; Lindson-Hawley, N.; Aveyard, P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014, 348, g1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.; McNeill, A.; Aveyard, P. Does deterioration in mental health after smoking cessation predict relapse to smoking? BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K. Physical activity and muscle-brain crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, S. Physical activity and mental health: Evidence is growing. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, A.H.; Wennberg, P.; Sinadinovic, K. Changes in mental and physical well-being among problematic alcohol and drug users in 12-month internet-based intervention trials. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2015, 29, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egholm, J.W.; Pedersen, B.; Møller, A.M.; Adami, J.; Juhl, C.B.; Tønnesen, H. Perioperative alcohol cessation intervention for postoperative complications. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).