Evaluating Family Planning Organizations Under China’s Two-Child Policy in Shandong Province

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.1.1. Shandong Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission Information System

2.1.2. Shandong Provincial Bureau of Statistics

2.1.3. Interview Data

2.2. Definitions

2.2.1. Funding of Family Planning Institutions

2.2.2. Expenditure of Family Planning Institutions

2.2.3. The Social Compensation Fee

2.3. Statistic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Family Planning Funding

3.2. Family Planning Expenditure

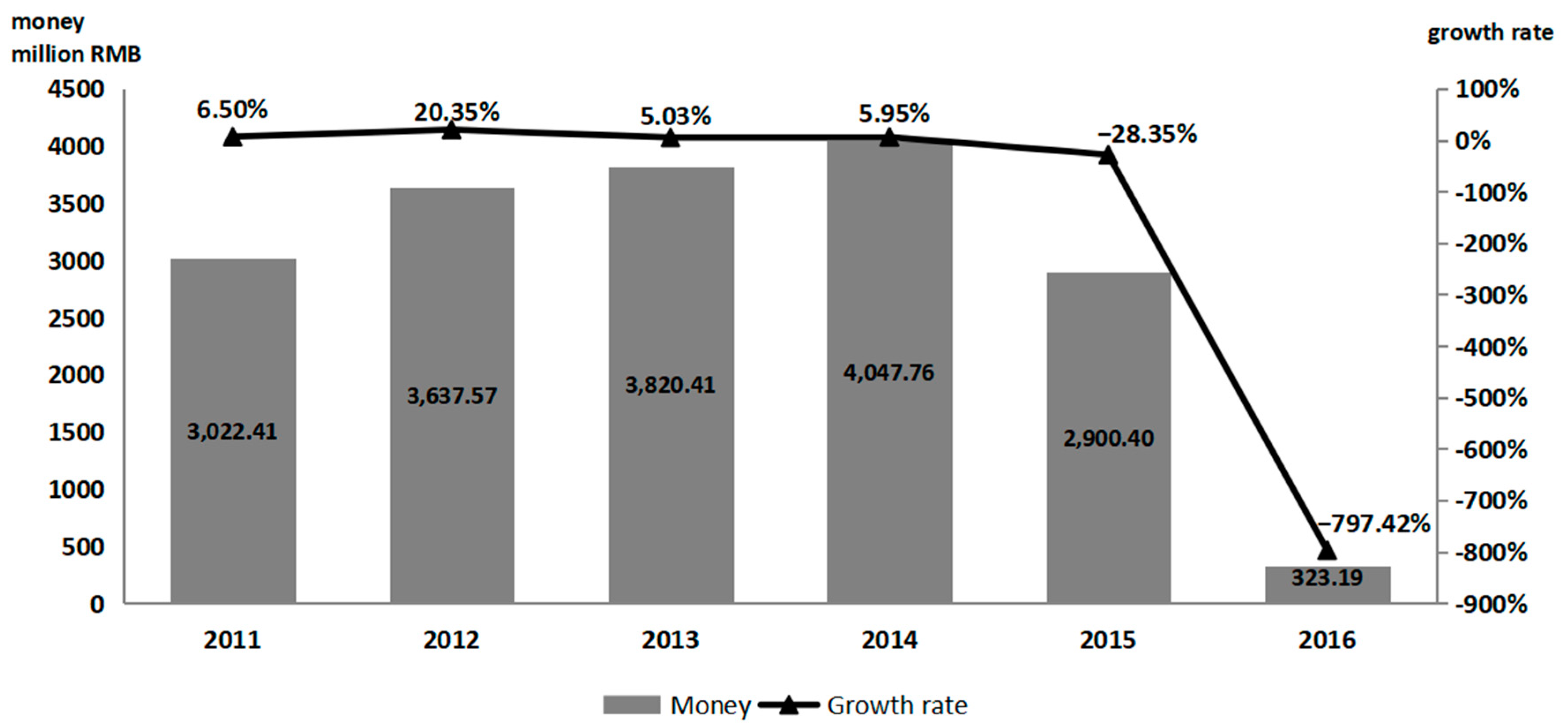

3.3. Social Compensation Fee

3.4. Interview Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Douglass, C.N. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass, C.N. Understanding the Process of Economic Change; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Notice of the State Council on the Establishment of Institutions. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2013-03/21/content_7613.htm (accessed on 16 May 2019).

- Zhang, P.L. The Problems in the Integration of Health and Family Planning Institutions in Xingtai City are Studied. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.L. Research on the Transformation of the Network Service Mode of Family Planning at the Grassroots Level in the New Era. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Technology and Business University, Chongqing, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.Y. Contemporary Chinese Population Policy Research; Beijing Intellectual Property Right Press: Beijing, China, 2005; pp. 144–147. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. A Review of China’s Fertility Policy Adjustment from the Perspective of Gender. Soc. Sci. Heilongjiang 2018, 5, 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.X. Historical Research on Family Planning of Contemporary China. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2004. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R.F.; Deng, F. A Brief Discussion on the Reform of the Ministry of Population and Family Planning Management in China. J. Chengdu Inst. Adm. 2011, 5, 13–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.H. The One-Child Policy and Gender Equality in Education in China: Evidence from Household Data. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2012, 33, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Shi, X. The impact of China’s one-child policy on intergenerational and gender relations. Contemp. Soc. Sci. J. Acad. Soc. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.X.; Su, J.M.; Xia, M. The Super-Ministry Reform and the New Thinking on the Family Planning Work. Popul. Res. 2013, 37, 104–109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M.W.; Gavin, L.; Zapata, L.B.; Bornstein, M.; Mautone-Smith, N.; Moskosky, S.B. Four aspects of the scope and quality of family planning services in US publicly funded health centers: Results from a survey of health center administrators. Contraception 2016, 94, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.D.; Therese, H. Family size, fertility preferences, and sex ratio in China in the era of the one child family policy: Results from national family planning and reproductive health survey. BMJ 2006, 333, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yong, C.; Baochang, G. Population, Policy, and Politics: How Will History Judge China’s One-Child Policy? Popul. Dev. Rev. 2013, 38, 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.Z. Population Policy and Program in China Challenge and Prospective. Tex. Int. Law J. 2000, 35, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.J.; Robert, D.R.; Minja, K.C.; Li, X.R.; Cui, H.Y. Effects of population policy and economic reform on the trend in fertility in Guangdong province, China, 1975–2005. Popul. Stud. (Camb.) 2010, 64, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Li, S.C. The Cost-Benefit Analysis of Family Planning—Take Shaanxi Province as an Example. Northwest Popul. J. 1998, 3, 45–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hector, C.; Vestal, W.P.; Joseph, D.B. Three-Year Longitudinal Evaluation of the Costs of a Family Planning Program. Am. J. Public Health 1972, 62, 1647–1657. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.S. Research on the Mechanism of Public Financial Support for Population and Family Planning in China. Econ. Res. Ref. 2012, 45, 22–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, S.X. A Brief Analysis on the Transformation of Grassroots Family Planning Workers Under the Comprehensive Two-Child Policy. China Health Hum. Resour. 2016, 84–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.W. The Analysis of Administrative Law on the Payment of Social Compensation Fee for the Second Child. Study Rule Law Soc. 2017, 129–131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Year | Family Planning Investment Funds (RMB billion) (annual growth rate) | Total Provincial Financial Expenditure (RMB billion) (annual growth rate) | Proportion of Family Planning Funds in Financial Expenditure (%) | Permanent Residents (Million) | Per Capita Family Planning Funds (RMB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 5.90 | 500.21 | 1.18 | 96.37 | 61.22 |

| 2012 | 6.99 (18.47%) | 590.45 (18.04%) | 1.18 | 96.85 | 72.17 |

| 2013 | 8.47 (21.17%) | 668.88 (13.28%) | 1.27 | 97.33 | 87.02 |

| 2014 | 7.40 (−12.63%) | 717.73 (7.30%) | 1.03 | 97.89 | 75.60 |

| 2015 | 6.79 (−8.24%) | 825.00 (14.95%) | 0.82 | 98.47 | 68.96 |

| 2016 | 5.30 (−11.50%) | 875.52 (6.12%) | 0.61 | 99.47 | 53.28 |

| Year | National Level | Provincial Level | City Level | County Level | Township Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 126.92 (2.34%) | 220.02 (4.05%) | 366.98 (6.76%) | 2076.91 (38.23%) | 2641.61 (48.63%) |

| 2012 | 203.46 (3.07%) | 305.26 (4.60%) | 485.57 (7.32%) | 2683.94 (40.46%) | 2955.07 (44.55%) |

| 2013 | 0 | 364.05 (4.53%) | 742.02 (9.23%) | 3779.57 (47.00%) | 3155.66 (39.24%) |

| 2014 | 0 | 97.34 (1.27%) | 562.05 (7.34%) | 4426.18 (57.78%) | 2575.32 (33.62%) |

| 2015 | 0 | 456.53 (7.55%) | 542.15 (8.96%) | 3453.77 (57.08%) | 1597.79 (26.41%) |

| Year | Total (RMB million) | Interest-Oriented | Public Service | Capacity-Building | Management Operation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount (RMB million) | Percent | Amount (RMB million) | Percent | Amount (RMB million) | Percent | Amount (RMB million) | Percent | ||

| 2011 | 5650.98 | 1049.04 | 18.56% | 886.90 | 15.69% | 1009.04 | 17.86% | 2706.00 | 47.89% |

| 2012 | 6655.97 | 1413.01 | 21.23% | 1223.72 | 18.39% | 1108.26 | 16.65% | 2910.97 | 43.73% |

| 2013 | 8435.33 | 2070.99 | 24.55% | 1464.03 | 17.36% | 1280.92 | 15.19% | 3619.40 | 42.91% |

| 2014 | 8137.45 | 2273.95 | 27.94% | 1645.27 | 20.22% | 1497.35 | 18.40% | 2720.88 | 33.44% |

| 2015 | 7360.31 | 2644.65 | 35.93% | 1505.45 | 20.45% | 894.54 | 12.15% | 2315.67 | 31.46% |

| 2016 | 6036.20 | 2385.82 | 39.53% | 1486.29 | 24.62% | 349.94 | 5.80% | 1814.14 | 30.05% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Yang, F.; Sun, J.; Nicholas, S.; Wang, J. Evaluating Family Planning Organizations Under China’s Two-Child Policy in Shandong Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122121

Xu L, Yang F, Sun J, Nicholas S, Wang J. Evaluating Family Planning Organizations Under China’s Two-Child Policy in Shandong Province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(12):2121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122121

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Lizheng, Fan Yang, Jingjie Sun, Stephen Nicholas, and Jian Wang. 2019. "Evaluating Family Planning Organizations Under China’s Two-Child Policy in Shandong Province" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 12: 2121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122121

APA StyleXu, L., Yang, F., Sun, J., Nicholas, S., & Wang, J. (2019). Evaluating Family Planning Organizations Under China’s Two-Child Policy in Shandong Province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(12), 2121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122121