“In Their Own Voice”—Incorporating Underlying Social Determinants into Aboriginal Health Promotion Programs

Abstract

Aboriginal Health means not just the physical well-being of an individual but the social, emotional and cultural well-being of the whole Community in which each individual is able to achieve their full potential as a human being, thereby bringing about the total well-being of their Community.National Aboriginal Health Strategy (1989) [1].

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Participant Selection

2.3. Data Collection

- (1)

- An initial group or individual discussion where the study was explained, consent was obtained, information packs (including cameras, research questions, and instructions) were provided, and questions were answered;

- (2)

- participants went away with their cameras and took photos loosely based on the three research questions; and

- (3)

- photos were then used to facilitate the yarning (story telling) sessions with the authors to address the research questions.

- (1)

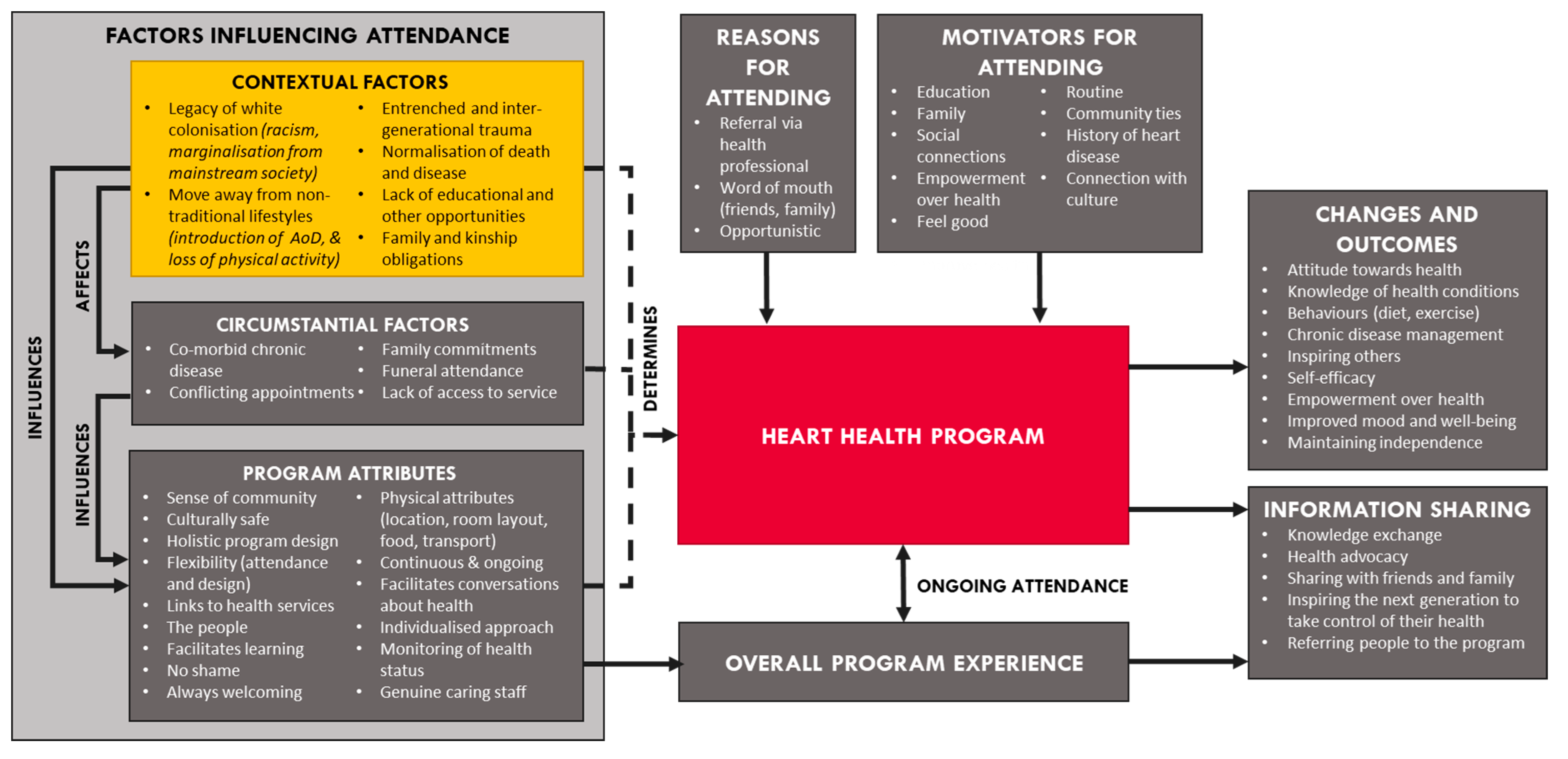

- Why do you come to the Heart Health program (what motivated you to start coming, what motivates you to keep coming, what things make it hard for you to come along sometimes)?

- (2)

- What changes have you made in your life since being involved in the Heart Health program (have you seen any benefits from the changes you have made)?

- (3)

- Have you shared the information you have learnt from the Heart Health program with other people (e.g., friends or family)?

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Legacy of White Colonisation

Where I come from I wasn’t able to talk, to look at people, white people…I worked at community welfare for a while. When anyone comes to the desk you have to attend to them. I had great difficulty with that…If it was a policeman, I would not go near them.

The fact that you talk to my Elders with respect in a caring manner I want to engage with you. So that’s the beauty of this program…it allows us to address our health culturally with our families and our aunties and our uncles and our Elders.

…if you’re going to get guest speakers in—so when the guys came from the universities… I meet them the week before and spend about an hour-and-a-half to two-hours teaching them how to yarn to a group, and how to present in a way that the clients would actually get it, rather than them trying to give a university format presentation.

3.2. Impact of Moving Away from Traditional Lifestyles

I’m a hunter, I’m a Noongar (original inhabitants of the geographical area in the south-west of Western Australia), and we used to go hunting a lot…so walking’s always been in my life and culture. It was not until the white man came that we got cars and we decided not to walk. So I’ve always walked. I’ve walked off the reserve into schools. I’ve walked off things, so walking’s always been part of my life.

The other week, we did running like a dingo… and [imagine] walking through the bush…

Communication is part of the thing that keeps people together. When Aboriginal people lived on reserves they were a group of people that communicated, they helped each other, they talked to people. You talk about a village raises a child, this is exactly what happened on reserves, years ago, when people actually looked after each other. You took concern for each other, you talked to each other. Somebody’s kid did something wrong, you told that kid off. They said, oh, thank you for stopping my kid from doing something silly. The white man come along and isolated everybody.

But, no, but seriously in a holistic approach you fellows want us to address our diabetes and just talk about your toes drop off and things like that. Well things drop off and we shouldn’t not talk about it…

We all talk about our [illness]. So that’s good because I’ve never seen that anywhere else where you are sitting down talking about what your numbers are for your diabetes and all that.

3.3. Hindrance of Educational Opportunities

I was told I was dumb in primary school. I would never amount to anything, and that I had the lowest IQ. So I did give up a bit of the schooling, and concentrated on the sports.

…my pop taught me to write really early…I was his little secretary…When I got to high school, I loved it. For someone who was supposed to be that dumb at maths, all I wanted was to do long division, someone to show me and my teacher, she wouldn’t come to show me. That’s all I wanted.

All I wanted, was him [her son] to have a good education. So I think that’s one thing I wanted more than anything because I never had the chance. I was stopped.

I’d have loved to have learned it when I was 15 years old…But they [my parents] didn’t teach us about health because they didn’t know about health themselves.

…learn to be flexible, and that’s why the diabetic education is one that you can actually—if you miss out in one lecture or you come in half way through, you just go back and start again. So it’s just a continuous circle, you know? And that’s how things are with Aboriginal education. Everything’s in circles, not in lines.

It’s interesting watching some of the nursing students…because they’ll give it to the client and the client’s got no idea. Like [client] when he used to come in at the beginning and he had no idea what he was doing and we couldn’t work out why his sugars were ridiculous, but he used to pop it in, go boom and then take it straight out and it [the insulin] would be spraying all over the floor. So no wonder his sugars are 26 [mmol/L]. So then it’s like push your finger on it and count up to 10.

3.4. Entrenched and Inter-Generational Trauma

I try and create an atmosphere where it’s not intimidating. So if you haven’t done your sugars for three months or had your tablets for two weeks I’m not going to make you wrong for that…

I came on board as the Stolen Gen worker…I come in here [Heart Health] to say hello to my Stolen Gen clients. That’s my time to give them information, see them about camps, see how they’re going, just check on generally how they’re feeling, if they want any help and support…

At the end of the day, everybody who walks in this building is a client of Derbarl. Everybody who walks in here is a potential client of Stolen Gen because at least 98 per cent of them are first, second or third generation. Or their kids or grandkids or their niece or nephew or someone has been taken away and removed, whether it’s the old Native Welfare, the DCP (Department of Child Protection (now the Department of Communities, Child Protection and Family Support)), whoever.

I was 15 years old when I lost my mum. She had terminal cancer…As children we had to deal with it and there was nothing out there as any counselling. There was nothing. We just had to deal with it the best we can. My dad hit a brick wall. He just drowned himself in alcohol…

But I was raised on a reserve and that’s where all of these things happened. Like the drinking, fighting, belting. I was only 13 or 14 I think.

I do alcohol and I do cigarettes…but when it’s instilled in a person—you know—and … looking at what you see your parents do, looking at what you see your uncles do and the whole family, living on a reserve...it just becomes the norm.

3.5. The Normalisation of Premature Death and Inevitability of Disease

I am 55 years old. My uncles, that is my dad’s brothers, I thought they were old and they were only 40 when they passed away.

I looked at diabetes as a generational thing in my mob…my mum and my aunties…Generationally it hasn’t changed too much…I just thought it happened to people mainly women because that’s what I grew up with…sometimes there’s an expectation my family’s got it so I’m going to get it so it doesn’t matter.

My dad—he’s had a CABG [Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting] and a triple bypass…His sister’s had triple bypasses. His brother and my mother’s brother have had heart disease—my uncle—a heart attack…

I haven’t been able to go back home for funerals and that because it’s a nine-hour drive and doctor wouldn’t let me travel. I ended up travelling to go to my sister’s funeral. But then I couldn’t go to my brother’s. It was too far for me at the time.

My Nanna passed away now. I can’t go to her funeral because it’s the same time as my Auntie’s.

3.6. Kinship and Other Family Obligations

We have a lot of our oldies here in their nineties or nearly nineties and they’ve got their children there. So it is that family thing of keeping going.

I met a few other relatives at Heart Health. So I’m always bringing my family tree with me too now so we all sit down and talk about…

…just telling other people about it; my cousins come for instance. I’ve got a whole lot of cousins from different sides of the family that come here…my mum started coming here before I did…I’m trying to get my sister to come at the moment.

What we do is just what every other program is doing around the place. We check everybody’s blood pressure, we check everybody’s sugars—but the how we do it is a bit different. The how is it’s culturally safe. You’re not right or wrong whether you come in for five minutes or two hours. If you want to walk in and out and rant and rave then that’s fine.

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Aboriginal Strategy Working Party. A National Aboriginal Health Strategy; Department of Aboriginal Affairs: Canberra, Australia, 1989.

- Gracey, M.; King, M. Indigenous health part 1: Determinants and disease patterns. Lancet 2009, 374, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Health and Welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Vos, T.; Barker, B.; Begg, S.; Stanley, L.; Lopez, A.D. Burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: The Indigenous health gap. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants and the health of Indigenous Australians. Med. J. Aust. 2011, 194, 512–513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reilly, R.E.; Doyle, J.; Bretherton, D.; Rowley, K.G.; Harvey, J.L.; Briggs, P.; Charles, S.; Calleja, J.; Patten, R.; Atkinson, V. Identifying psychosocial mediators of health amongst Indigenous Australians for the Heart Health Project. Ethnic Health 2008, 13, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiris, D.; Brown, A.; Cass, A. Addressing inequities in access to quality health care for indigenous people. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2008, 179, 985–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, L.; Kendall, E. Culturally appropriate methods for enhancing the participation of Aboriginal Australians in health-promoting programs. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2011, 22, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 10, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, R.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Barclay, L.; Chenhall, R.; Nagel, T. Developing a best practice pathway to support improvements in Indigenous Australians’ mental health and well-being: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, J.D. Historical, social and biological understanding is needed to improve Aboriginal health. Recent Adv. Microbiol. 1997, 5, 257–334. [Google Scholar]

- Rasanathan, K.; Montesinos, E.V.; Matheson, D.; Etienne, C.; Evans, T. Primary health care and the social determinants of health: Essential and complementary approaches for reducing inequities in health. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2011, 65, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, J.; Nelson, J.; Brooks, R.; Atkinson, C.; Ryan, K. Addressing Individual and Community Transgenerational Trauma. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., Walker, R., Eds.; Kulunga Research Network: West Perth, Australia, 2014; pp. 289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Durey, A.; Thompson, S.C. Reducing the health disparities of Indigenous Australians: Time to change focus. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markwick, A.; Ansari, Z.; Sullivan, M.; Parsons, L.; McNeil, J. Inequalities in the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: A cross-sectional population-based study in the Australian state of Victoria. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, O.; Lisy, K.; Davy, C.; Aromataris, E.; Kite, E.; Lockwood, C.; Riitano, D.; McBride, K.; Brown, A. Enablers and barriers to the implementation of primary health care interventions for Indigenous people with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durey, A.; McAullay, D.; Gibson, B.; Slack-Smith, L. Aboriginal Health Worker perceptions of oral health: A qualitative study in Perth, Western Australia. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durey, A. Reducing racism in Aboriginal health care in Australia: Where does cultural education fit? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2010, 34, s87–s92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, E.; Barnett, L. Principles for the development of Aboriginal health interventions: Culturally appropriate methods through systemic empathy. Ethnic Health 2014, 20, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boddington, P.; Räisänen, U. Theoretical and Practical Issues in the Definition of Health: Insights from Aboriginal Australia. J. Med. Philos. 2009, 34, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimer, L.; Dowling, T.; Jones, J.; Cheetham, C.; Thomas, T.; Smith, J.; McManus, A.; Maiorana, A.J. Build it and they will come: Outcomes from a successful cardiac rehabilitation program at an Aboriginal Medical Service. Aust. Health Rev. 2013, 37, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, L.W. Closing the chasm between research and practice: Evidence of and for change. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2014, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koster, R.; Baccar, K.; Lemelin, R.H. Moving from research ON, to research WITH and FOR Indigenous communities: A critical reflection on community-based participatory research. Can. Geogr. 2012, 56, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.; Burns, C.; Liebzeit, A.; Ryschka, J.; Thorpe, S.; Browne, J. Use of participatory research and photo-voice to support urban Aboriginal healthy eating. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2012, 20, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erick, W.; Mooney-Somers, J.; Akee, A.; Maher, L. Resilience to blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections: The development of a participatory action research project with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Townsville. Aborig. Isl. Health Work J. 2008, 32, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, G.; Fredericks, B.; Adams, K.; Finlay, S.; Andy, S.; Briggs, L.; Hall, R. Having a yarn about smoking: Using action research to develop a ‘no smoking’policy within an Aboriginal Health Organisation. Health Policy 2011, 103, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, P.S.; Murphy, G.J. Cultural identification in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander AIDS education. Aust. J. Public Health 1992, 16, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, E. Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, National Report; Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra, Australia, 1991.

- Jardine, C.G.; James, A. Youth researching youth: Benefits, limitations and ethical considerations within a participatory research process. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2012, 71, 18415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Edu. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclean, K.; Woodward, E. Photovoice Evaluated: An Appropriate Visual Methodology for Aboriginal Water Resource Research. Geogr. Res. 2013, 51, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C. Youth participation in photovoice as a strategy for community change. J. Commun. Pract. 2006, 14, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuis, S.K.; Willows, N.; Alexander First, N.; Jardine, C. Through the lens of our cameras: Children’s lived experience with food security in a Canadian Indigenous community. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolahdooz, F.; Nader, F.; Yi, K.J.; Sharma, S. Understanding the social determinants of health among Indigenous Canadians: Priorities for health promotion policies and actions. Glob. Health Action 2015, 8, 27968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkie, M. Bringing Them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families; Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission: Sydney, Australia, 1997.

- Australian Government. About NAIDOC Week. Available online: http://www.naidoc.org.au/about (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- McKay, D. Uluru Statement: A Quick Guide; Law and Bills Digest Section, Parliament of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2017.

- Carson, B.; Dunbar, T.; Chenhall, R.D.; Bailie, R. Social Determinants of Indigenous Health; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea, K. Traditional diet and food preferences of Australian Aboriginal hunter-gatherers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 1991, 334, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Biomedical Reserch 2012–2013; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2014.

- Taylor, K.; Guerin, P. Health Care and Indigenous Australians: Cultural Safety in Practice; Macmillan Education AU: Victoria, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch, I.S. Health literacy: Addressing the health and education divide. Health Promot. Int. 2001, 16, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, E.B.; Woolf, S.H.; Haley, A. Understanding the relationship between education and health: A review of the evidence and an examination of community perspectives. In Population Health: Behavioral and Social Science Insights; Kaplan, R.M., Spittel, M.L., David, D.H., Eds.; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health: Rockville, MD, USA, 2015; pp. 347–384. [Google Scholar]

- Bombay, A.; Matheson, K.; Anisman, H. Intergenerational Trauma: Convergence of multiple processes among First Nations peoples in Canada. J. Aborig. Health 2009, 5, 6–47. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell, T. Historical Trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska Communities: A Multilevel Framework for Exploring Impacts on Individuals, Families, and Communities. J. Interpers. Violence 2008, 23, 316–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieg, A. The experience of collective trauma in Australian Indigenous communities. Australas. Psychiatry 2009, 17, S28–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honorato, B.; Caltabiano, N.; Clough, A.R. From trauma to incarceration: Exploring the trajectory in a qualitative study in male prison inmates from north Queensland, Australia. Health Justice 2016, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A.; Fleming, K.; Markwick, N.; Morrison, T.; Lagimodiere, L.; Kerr, T. “They treated me like crap and I know it was because I was Native”: The healthcare experiences of Aboriginal peoples living in Vancouver’s inner city. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 178, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machtinger, E.L.; Cuca, Y.P.; Khanna, N.; Rose, C.D.; Kimberg, L.S. From Treatment to Healing: The Promise of Trauma-Informed Primary Care. Women Health Issues 2015, 25, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brett, J.; Dawson, A.; Ivers, R.; Lawrence, L.; Barclay, S.; Conigrave, K. Healing at Home: Developing a Model for Ambulatory Alcohol “Detox” in an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service. Int. J. Indig. Health 2017, 12, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, E. A synthesis of the literature on trauma-informed care. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 36, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commonwealth of Australia Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2018; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, B.; Frazer, R. “It’s Like Going to a Cemetery and Lighting a Candle”: Aboriginal Australians, Sorry Business and social media. AlterNative 2015, 11, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Bilney, J.; Bycroft, N.; Cockatoo-Collins, D.; Creighton, G.; Else, J.; Faulkner, C.; French, J.; Liddle, T.; Miller, A. Closing the gap: Support for Indigenous loss. Aust. Nurs. Midwifery J. 2012, 19, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Canuto, K.J.; Spagnoletti, B.; McDermott, R.A.; Cargo, M. Factors influencing attendance in a structured physical activity program for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in an urban setting: A mixed methods process evaluation. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzenellenbogen, J.M.; Haynes, E.; Woods, J.A.; Bessarab, D.; Durey, A.; Dimer, L.; Maiorana, A.; Thompson, S.C. Information for Action: Improving the Heart Health Story for Aboriginal People in Western Australia (BAHHWA Report); Western Australian Centre for Rural Health, University of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Derbarl Yerrigan Health Service Inc. 2016–2017 Annual Report; Derbarl Yerrigan Health Service Inc.: Perth, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bécares, L.; Cormack, D.; Harris, R. Ethnic density and area deprivation: Neighbourhood effects on Māori health and racial discrimination in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 88, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coimbra, C.E.A.; Santos, R.V.; Welch, J.R.; Cardoso, A.M.; de Souza, M.C.; Garnelo, L.; Rassi, E.; Follér, M.L.; Horta, B.L. The First National Survey of Indigenous People’s Health and Nutrition in Brazil: Rationale, methodology, and overview of results. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Heart Health Program | Traditional Hospital Cardiac Programs | |

|---|---|---|

| Referral | No formal process, mostly word of mouth or opportunistic due to location. | Formal referral from doctor or cardiac nurse post cardiac event. |

| Attendance | As often as wanted, program runs weekly. No specific attendance required. | Set period, usually 4–6 weeks long. Attendance at every session usually required. |

| Health prerequisites | Nil, program provides information on any health issues requested by participants with primary focus on cardiac issues and diabetes. Do not need to have any chronic diseases or cardiac issues to attend. | Post cardiac event. |

| Transport | Provided to anyone who requires it at no cost. | Make own arrangements. |

| Food | Morning tea and lunch provided. | Not provided. |

| Exercise | Group walk and exercise-physiologist led rehabilitation exercises (walk pending weather). | Dependent on program. |

| Structure | Diabetes round-table discussion, followed by a group walk and morning tea. Group yarning on weekly health topic (session can be facilitator led, participant led, or a more formal presentation style talk depending on topic and presenter); lunch is provided during this session. Followed by weight exercises. Finished with a cardiac-specific discussion; sharing of personal experiences and asking questions is encouraged. Participants are free to leave at any point. Blood pressure and insulin measured throughout the day. | Typically PowerPoint presentation while seated at desks. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vallesi, S.; Wood, L.; Dimer, L.; Zada, M. “In Their Own Voice”—Incorporating Underlying Social Determinants into Aboriginal Health Promotion Programs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071514

Vallesi S, Wood L, Dimer L, Zada M. “In Their Own Voice”—Incorporating Underlying Social Determinants into Aboriginal Health Promotion Programs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(7):1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071514

Chicago/Turabian StyleVallesi, Shannen, Lisa Wood, Lyn Dimer, and Michelle Zada. 2018. "“In Their Own Voice”—Incorporating Underlying Social Determinants into Aboriginal Health Promotion Programs" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 7: 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071514

APA StyleVallesi, S., Wood, L., Dimer, L., & Zada, M. (2018). “In Their Own Voice”—Incorporating Underlying Social Determinants into Aboriginal Health Promotion Programs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7), 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071514