Suicidal Ideation and Healthy Immigrant Effect in the Canadian Population: A Cross-Sectional Population Based Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey

2.2. Outcome Variable

2.3. Primary Exposure Variable

2.4. Confounding Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Projections of Mortality and Causes of Death. Available online: http://www.who.int/http://healthinfo/global_burden_disease/projections/en/9 (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/131056/1/9789241564779_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Statistics Canada Leading Causes of Death by Age Group and Sex. Available online: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- CDC Cost of Injury Report. Available online: https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/nfirates.html (accessed on 12 January 2018).

- Nock, M.K.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.J.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.; Beautrais, A.; Bruffaerts, R.; Chiu, W.T.; de Girolammo, G.; Gluzman, S.; et al. Cross-National Prevalence and Risk Factors for Suicidal Ideation, Plans and Attempts. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 192, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, G.; Angst, J.; Nock, M.K.; Ruscio, A.M.; Walters, E.E.; Kessler, R.C. A risk index for 12-month suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 1747–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, Y.R.; Lee, H.Y.; So, E.S. Suicidal ideation and associated factors by sex in Korean adults: A population-based cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Public Health 2011, 56, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Lee, H. Factors Associated with Suicidal Ideation: The Role of Context. J. Public Health 2012, 35, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, P.S.; Chi, I.; Chiu, H.; Wai, K.C.; Conwell, Y.; Caine, E. A prevalence study of suicide ideation among older adults in Hong Kong SAR. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2003, 18, 1056–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.J.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.M.; Hong, J.P.; Won, S.; Cho, S.; Kim, J.; Chang, S.M.; Lee, D.; Lee, H.W.; et al. Lifetime Prevalence and Correlates of Suicidal Ideation, Plan, and Single and Multiple Attempts in a Korean Nationwide Study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada Immigrant Population in Canada 2016 Census of Population. Available online: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2017028-eng.htm (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- Statistics Canada Immigration and Diversity: Population Projections for Canada and its Regions 2011 to 2036. Available online: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-551-x/91-551-x2017001-eng.htm (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- Cunningham, S.A.; Ruben, J.D.; Narayan, K.M.V. Health of Foreign-Born People in the United States: A Review. Health Place 2008, 14, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moullan, Y.; Jusot, F. Why is the ‘Healthy Immigrant Effect’ different between European Countries? Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24 (Suppl. 1), 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anikeeva, O.; Bi, P.; Hiller, J.E.; Ryan, P.; Roder, D.; Han, G. Trends in Cancer Mortality Rates among Migrants in Australia: 1981–2007. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012, 36, e74–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beiser, M. The Health of Immigrants and Refugees in Canada. Can. J. Public Health/Revue Can. Sante’e Publique 2005, 96 (Suppl. 2), S30–S44. [Google Scholar]

- Vang, Z.M.; Sigouin, J.; Flenon, A.; Gagnon, A. Are Immigrants Healthier Than Native-Born Canadians? A Systematic Review of the Healthy Immigrant Effect in Canada. Ethn. Health 2017, 22, 209–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, J. Mental Health of Canada’s Immigrants [Canadian Community Health Survey—2002 Annual Report]. Health Rep. 2002, 13, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Aglipay, M.; Colman, I.; Chen, Y. Does the Healthy Immigrant Effect Extend to Anxiety Disorders? Evidence from a Nationally Representative Study. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2013, 15, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, V. Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540–2015; Dundurn: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abraido-Lanza, A.F.; Dohrenwend, B.P.; Ng-Mak, D.S.; Turner, J.B. The Latino Mortality Paradox: A Test of the “Salmon Bias” and Healthy Migrant Hypotheses. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Narasiah, L.; Munoz, M.; Rashid, M.; Ryder, A.G.; Guzder, J.; Hassan, G.; Rousseau, C.; Pottie, K. Common Mental Health Problems in Immigrants and Refugees: General Approach in Primary Care. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2011, 183, E959–E967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vang, Z.; Sigouin, J.; Flenon, A.; Gagnon, A. The healthy immigrant effect in Canada: A systematic review. Popul. Chang. Lifecourse Strateg. Knowl. Clust. Discuss. Pap. Ser./Un Rés. Stratég. Connaiss. Chang. Popul. Parcours Doc. Trav. 2015, 3, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada Canadian Community Health Survey Annual Component. Available online: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey (accessed on 2 January 2018).

- Bursac, Z.; Gauss, C.H.; Williams, D.K.; Hosmer, D.W. Purposeful Selection of Variables in Logistic Regression. Source Code Biol. Med. 2008, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borjas, G.J. International Differences in the Labor Market Performance of Immigrants; ERIC: Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 1988.

- Wu, Z.; Schimmele, C.M. Racial/Ethnic Variation in Functional and Self-Reported Health. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escarce, J.J.; Morales, L.S.; Rumbaut, R.G. The Health Status and Health Behaviors of Hispanics. In Hispanics and the Future of America; Tienda, M., Mitchell, F., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 362–409. [Google Scholar]

- Trovato, F.; Jarvis, G.K. Immigrant Suicide in Canada: 1971 and 1981. Soc. Forces 1986, 65, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovey, J.D. Acculturative Stress, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in Mexican Immigrants. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2000, 6, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viruell-Fuentes, E.A.; Miranda, P.Y.; Abdulrahim, S. More than Culture: Structural Racism, Intersectionality Theory, and Immigrant Health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, J.T.; Kennedy, S. Insights into the ‘Healthy Immigrant Effect’: Health Status and Health Service Use of Immigrants to Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 1613–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Women’s Mental Health: An Evidence Based Review; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Guruge, S.; Collins, E. (Eds.) Emerging Trends in Canadian Immigration and Challenges for Newcomers. In Working with Immigrant Women: Issues and Strategies for Mental Health Professionals; Centre for Addiction & Mental Health: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Delara, M. Social Determinants of Immigrant Women’s Mental Health. Adv. Public Health 2016, 2016, 9730162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eynan, R.; Langley, J.; Tolomiczenko, G.; Rhodes, A.E.; Links, P.; Wasylenki, D.; Goering, P. The Association between Homelessness and Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors: Results of a Cross-Sectional Survey. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2002, 32, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Categories | Total (%) | Suicidal Ideation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |||

| Lifetime suicidal ideation | 12,121 | 123 (10.19) | 10,886 (89.91) | |

| Immigrant identity (n = 12,002) | Yes | 1858 (15.48) | 157 (1.31) | 1701 (8.92) |

| No | 10,144 (84.52) | 1070 (14.17) | 9074 (75.6) | |

| Time since immigration (n = 1858) | 0 to 9 years | 285 (15.34) | 18 (0.97) | 267 (14.37) |

| 10 or more years | 1573 (84.66) | 139 (7.48) | 1434 (77.18) | |

| Combined immigration variable (n = 12,002) | Non-immigrant | 10,144 (84.51) | 1070 (8.91) | 9074 (75.6) |

| 0 to 9 years | 285 (2.37) | 18 (0.15) | 267 (2.22) | |

| 10 or more years | 1573 (13.11) | 139 (1.16) | 1434 (11.95) | |

| Age (n = 12,121) | Youth | 1240 (10.23) | 162 (1.34) | 1078 (8.89) |

| Young Adult | 1980 (20.17) | 221 (1.82) | 1759 (14.51) | |

| Middle adult | 4300 (33.89) | 518 (4.27) | 3782 (31.2) | |

| Senior | 4601 (31.7) | 334 (2.76) | 4267 (35.2) | |

| Gender (n = 12,121) | Male | 5293 (43.67) | 480 (3.96) | 4813 (39.71) |

| Female | 6828 (56.33) | 755 (6.23) | 6073 (50.1) | |

| Household income (n = 12,101) | <$20,000 | 1364 (11.27) | 247 (2.04) | 1117 (9.23) |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 2773 (22.92) | 301 (2.49) | 2472 (20.43) | |

| $40,000–$59,999 | 2331 (19.26) | 222 (1.83) | 2109 (17.43) | |

| $60,000–$79,999 | 1777 (14.68) | 161 (1.33) | 1616 (13.35) | |

| >$80,000 | 3856 (31.87) | 300 (2.48) | 3556 (29.39) | |

| Level of education (n = 11,954) | <Secondary school | 2316 (19.38) | 221 (1.85) | 2095 (17.53) |

| Secondary school | 2603 (21.78) | 294 (2.46) | 2309 (19.32) | |

| Some post-secondary | 536 (4.48) | 79 (0.66) | 457 (3.82) | |

| Post-secondary certificate | 6499 (54.37) | 623 (5.21) | 5876 (49.16) | |

| Chronic health conditions (n = 12,121) | Yes | 7701 (63.53) | 919 (7.58) | 6782 (55.95) |

| No | 4566 (37.67) | 316 (2.61) | 4104 (33.86) | |

| Diagnosed with mood disorder (n = 12,104) | Yes | 1090 (8.12) | 488 (4.03) | 602 (4.97) |

| No | 11,014 (91) | 743 (6.14) | 10,271 (84.86) | |

| Variable | Category | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper | Lower | ||||

| Immigrant (Ref: non-immigrant) | Yes | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.78 | 0.0004 |

| Time since immigration (Ref: 0 to 9 years) | 10 or more years | 2.04 | 1.00 | 4.17 | 0.0495 |

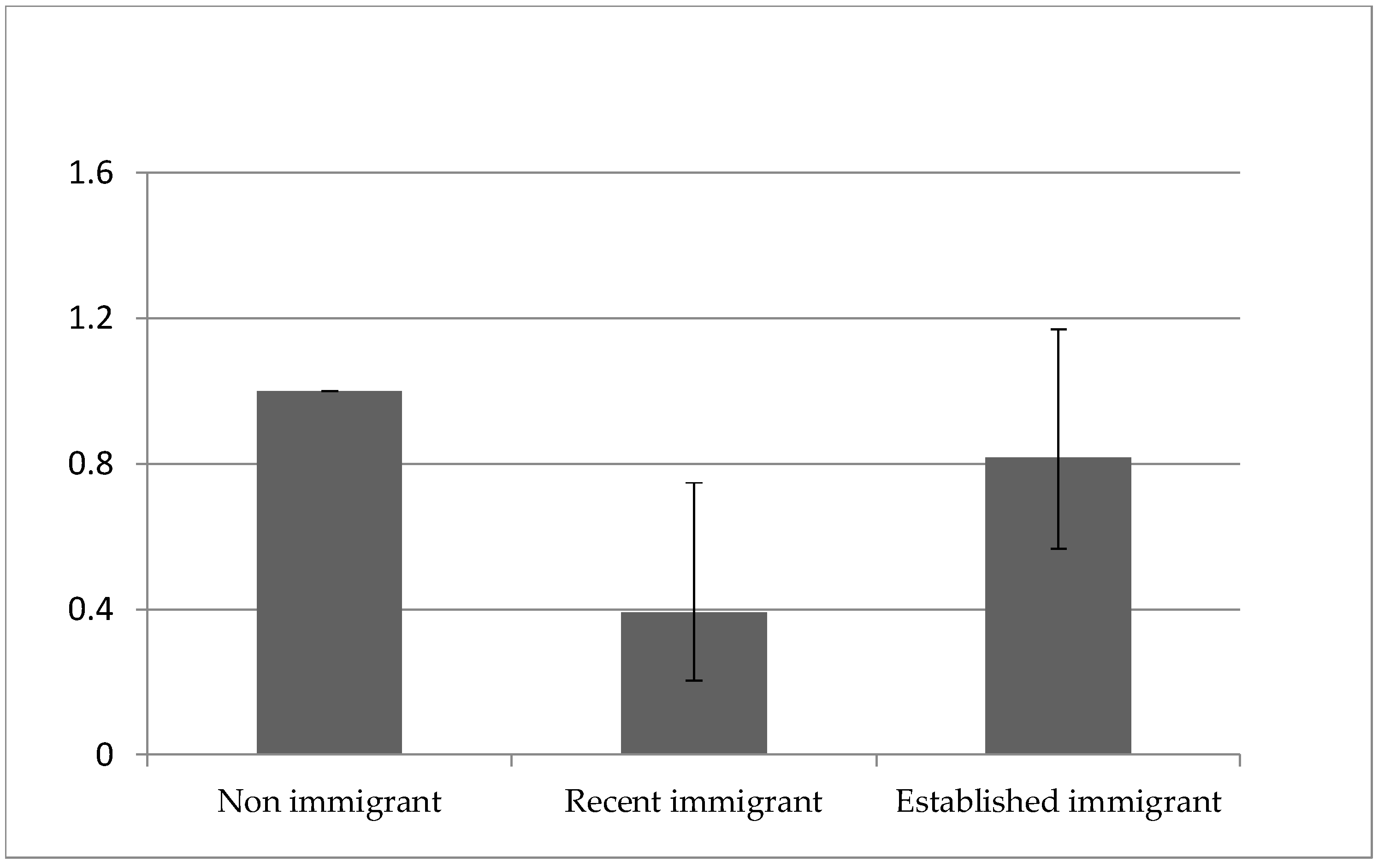

| Immigration identity (Ref: non- immigrant) | 0 to 9 years | 0.32 | 0.17 | 0.62 | 0.0003 |

| 10 or more years | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.93 | ||

| Age (Ref: senior) | Youth | 1.67 | 1.21 | 2.29 | 0.0133 |

| Young adult | 1.39 | 0.99 | 1.93 | ||

| Middle adult | 1.33 | 1.02 | 1.72 | ||

| Gender (Ref: male) | Female | 1.35 | 1.07 | 1.69 | 0.0102 |

| Household income (Ref: <$20,000) | $20,000–$39,999 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.93 | <0.0001 |

| $40,000–$59,999 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.52 | ||

| $60,000–$79,999 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.57 | ||

| >$80,000 | 0.399 | 0.29 | 0.56 | ||

| Level of education (Ref: <secondary school) | Secondary school | 0.85 | 0.64 | 1.12 | 0.1809 |

| Some post-secondary | 1.05 | 0.77 | 1.42 | ||

| Post-secondary certificate | 1.28 | 0.79 | 2.07 | ||

| Chronic health conditions (Ref: no) | Yes | 1.83 | 1.47 | 2.41 | <0.0001 |

| Diagnosed with mood disorder (Ref: no) | Yes | 11.04 | 8.47 | 14.38 | <0.0001 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | p-Value 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrant (Ref: no) | 9 or less years | 0.32 (0.17–0.62) | 0.26 (0.14–0.50) | 0.39 (0.20–0.75) | 0.0044 |

| 10 or more years | 0.66 (0.47–0.93) | 0.68 (0.48–0.96) | 0.82 (0.57–1.17) | 0.2673 | |

| Age (Ref: senior) | Youth | 1.88 (1.31–2.68) | 2.67 (1.81–3.94) | <0.0001 | |

| Young adult | 1.85 (1.29–2.66) | 2.01 (1.36–2.97) | 0.0005 | ||

| Middle adult | 1.56 (1.17–2.07) | 1.53 (1.11–2.10) | 0.0092 | ||

| Gender (Ref: male) | Female | 1.31 (1.04–1.64) | 1.14 (0.90–1.44) | 0.2945 | |

| Household income (Ref: >80,000) | <$20,000 | 2.97 (2.09–4.21) | 2.11 (1.45–3.08) | 0.0001 | |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 2.00 (1.43–2.81) | 1.695 (1.18–2.43) | 0.0042 | ||

| $40,000–$59,999 | 1.06 (0.78–1.43) | 0.93 (0.68–1.27) | 0.6399 | ||

| $60,000–$79,999 | 1.09 (0.78–1.53) | 1.00 (0.69–1.44) | 0.9946 | ||

| Chronic health conditions (Ref: no) | Yes | 1.77 (1.36–2.28) | <0.0001 | ||

| Diagnosed with mood disorder (Ref: no) | Yes | 9.7 (7.3–12.9) | <0.0001 |

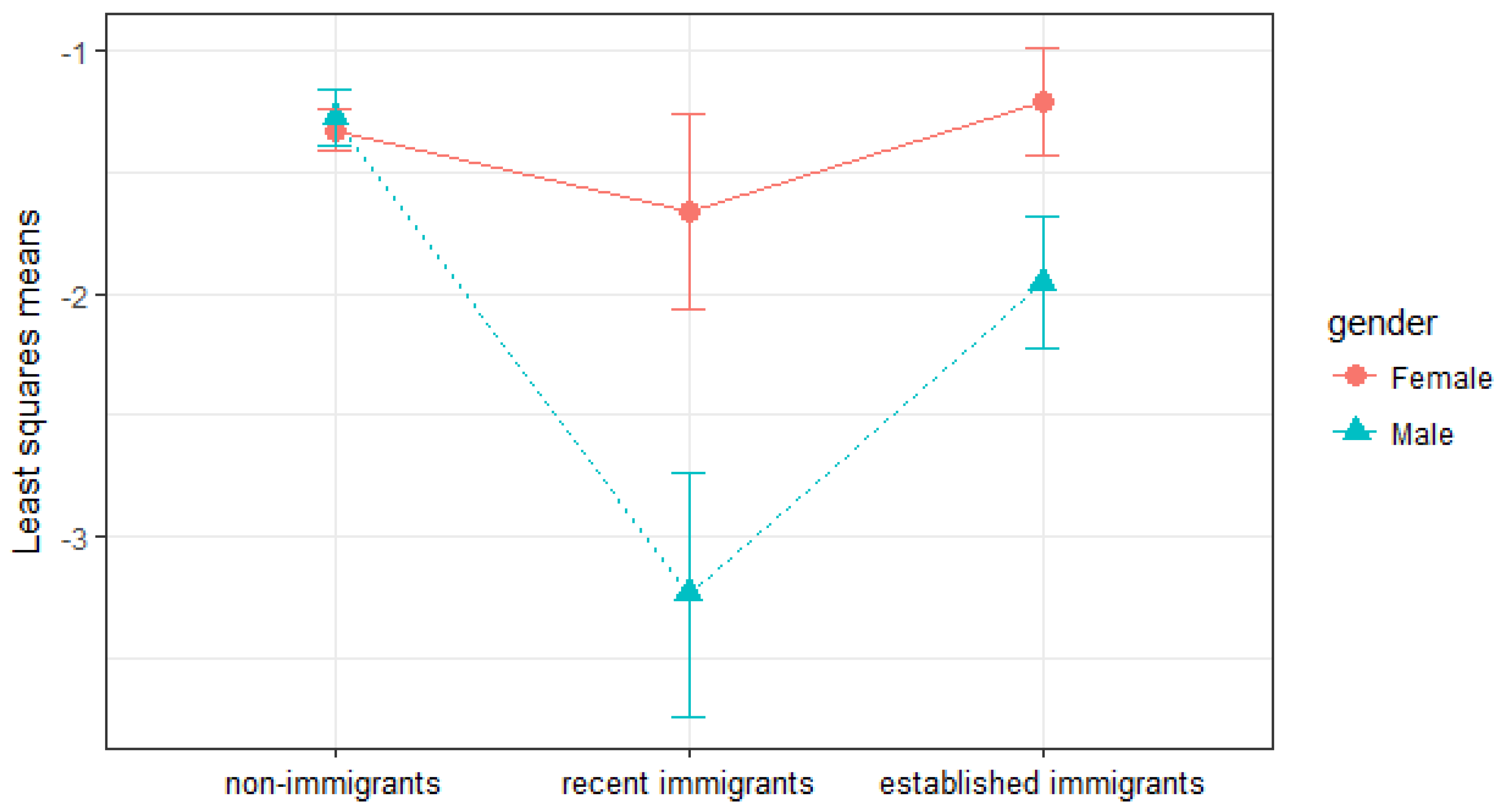

| aOR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Females | 0.6176 | |||

| Non-immigrant | 1.00 | - | - | - |

| Recent immigrant | 0.72 | 0.32 | 1.59 | 0.4118 |

| Established immigrant | 1.12 | 0.71 | 1.78 | 0.6179 |

| Males | <0.0001 | |||

| Non-immigrant | 1.00 | - | - | - |

| Recent immigrant | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.0001 |

| Established immigrant | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.89 | 0.0168 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elamoshy, R.; Feng, C. Suicidal Ideation and Healthy Immigrant Effect in the Canadian Population: A Cross-Sectional Population Based Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050848

Elamoshy R, Feng C. Suicidal Ideation and Healthy Immigrant Effect in the Canadian Population: A Cross-Sectional Population Based Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(5):848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050848

Chicago/Turabian StyleElamoshy, Rasha, and Cindy Feng. 2018. "Suicidal Ideation and Healthy Immigrant Effect in the Canadian Population: A Cross-Sectional Population Based Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 5: 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050848

APA StyleElamoshy, R., & Feng, C. (2018). Suicidal Ideation and Healthy Immigrant Effect in the Canadian Population: A Cross-Sectional Population Based Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(5), 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050848