Could Alcohol Abuse Drive Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators’ Psychophysiological Response to Acute Stress?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Electrodermal and Cardiorespiratory Recording

2.4. Psychological Measures

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. Stress Responses

3.2.1. Psychological State Profiles and Appraisal Scores

3.2.2. Electrodermal and Cardiorespiratory Responses

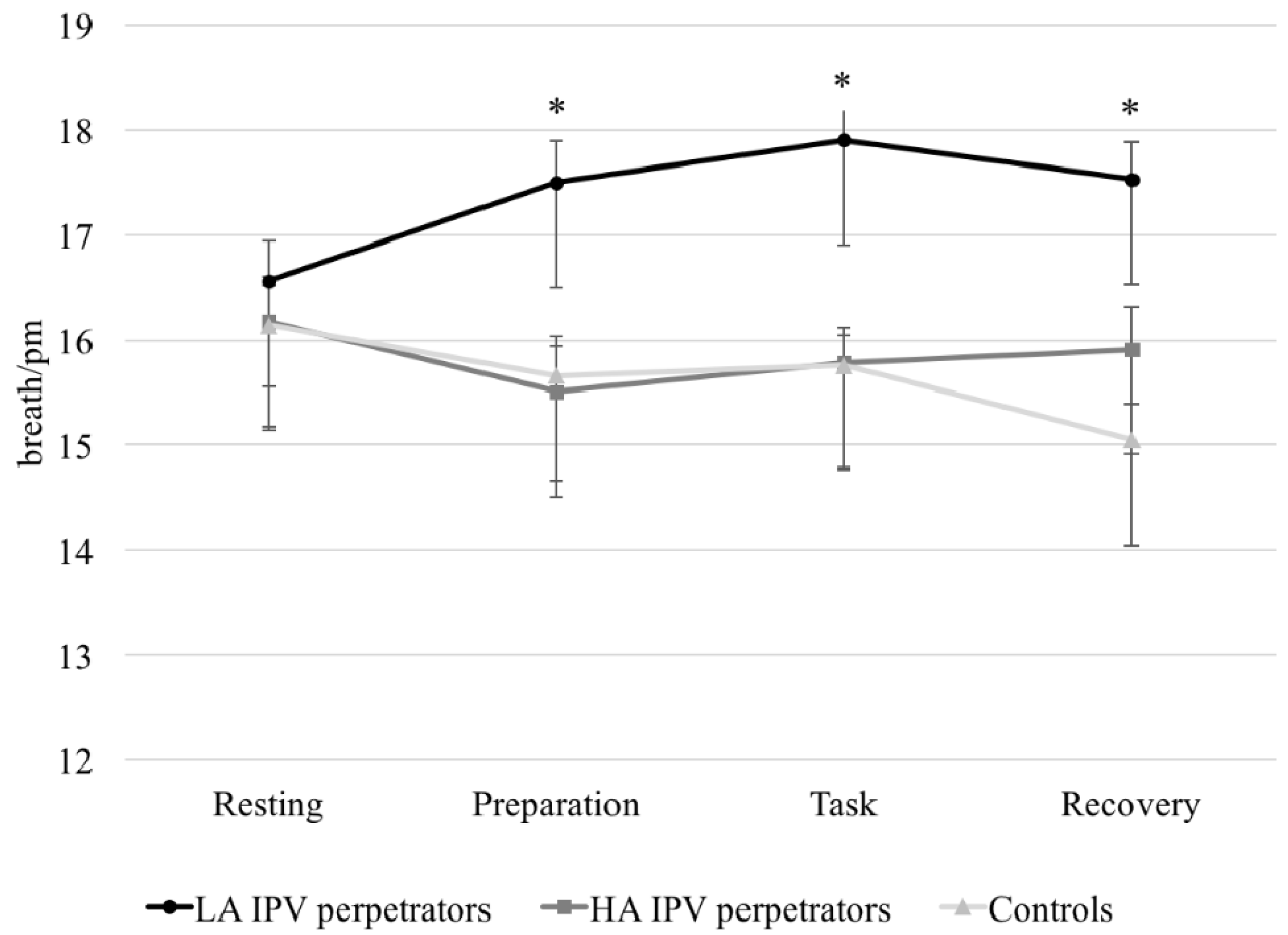

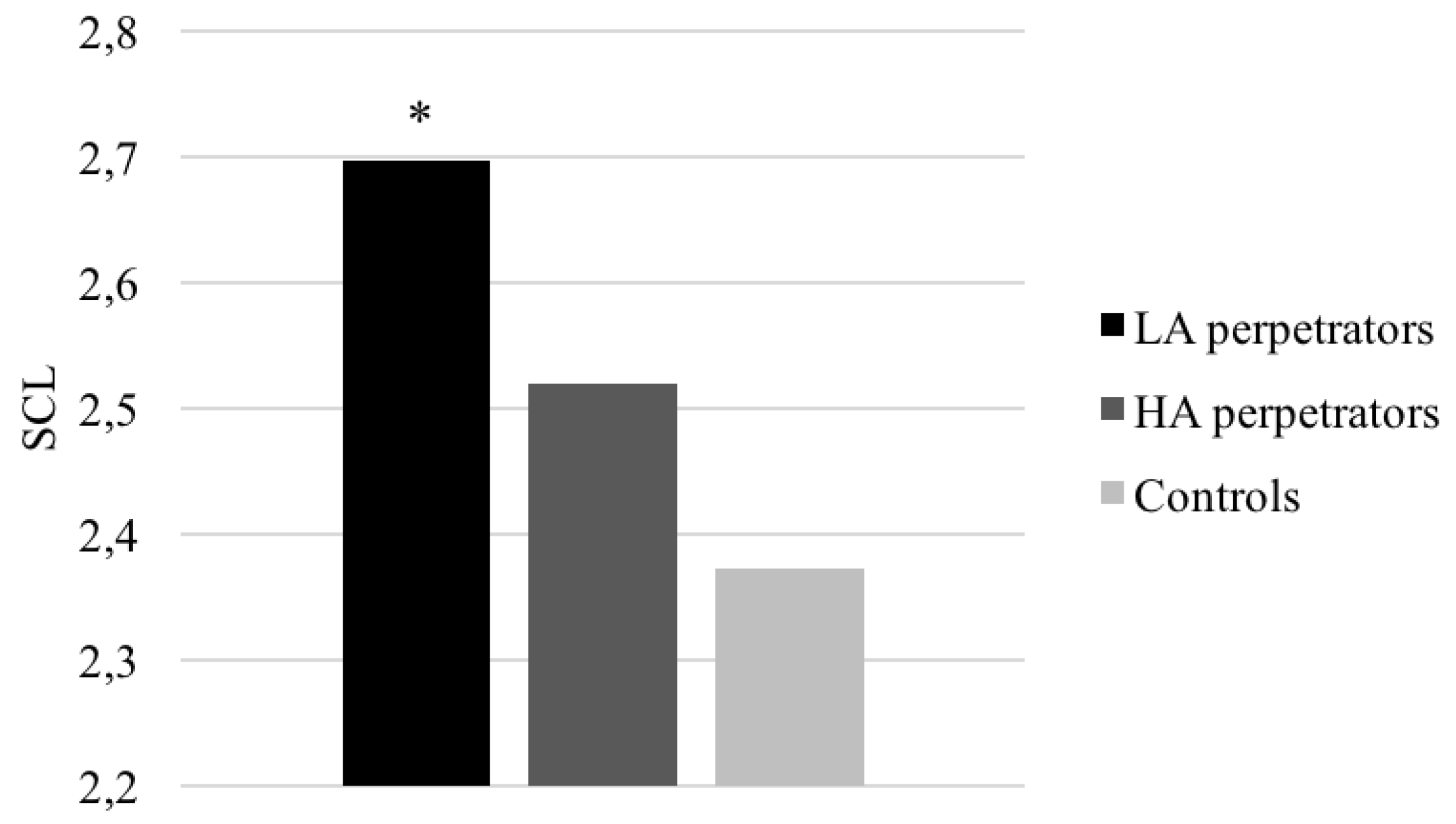

3.2.3. Differences between Groups in Electrodermal and Cardiorespiratory Variables in Response to a Set of Cognitive Tests

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babcock, J.C.; Green, C.E.; Webb, S.A.; Yerington, T.P. Psychophysiological Profiles of Batterers: Autonomic Emotional Reactivity as It Predicts the Antisocial Spectrum of Behavior among Intimate Partner Abusers. J. Exp. Psychopathol. 2005, 114, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.L.; Johnsen, B.H.; Thornton, D.; Waage, L.; Thayer, J.F. Facets of psychopathy, heart rate variability and cognitive function. J. Pers. Disord. 2007, 21, 568–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorber, M.F. Psychophysiology of Aggression, Psychopathy, and Conduct Problems: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, C.J. Psychophysiological correlates of aggression and violence: An integrative review. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 2543–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, A.; Lila, M.; Williams, R.K.; González-Bono, E.; Moya-Albiol, L. Skin conductance rises in preparation and recovery to psychosocial stress and its relationship with impulsivity and testosterone in intimate partner violence perpetrators. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013, 90, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, A.; Nunes-Costa, R.; Lila, M.; González-Bono, E.; Moya-Albiol, L. Cardiovascular reactivity to a marital conflict version of the Trier social stress test in intimate partner violence perpetrators. Stress 2014, 17, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, A.; Tanaka, A.; Chiara Haden, S. Biosocial bases of reactive and proactive aggression: The roles of community violence exposure and heart rate. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 36, 969–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vries-Bouw, D.; Popma, A.; Vermeiren, R.; Doreleijers, T.A.; Van De Ven, P.M.; Jansen, L. The predictive value of low heart rate and heart rate variability during stress for reoffending in delinquent male adolescents. Psychophysiology 2011, 48, 1597–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.P.; Cash, C.; Rankin, C.; Bernardi, A.; Koenig, J.; Thayer, J.F. Resting heart rate variability predicts self-reported difficulties in emotion regulation: A focus on different facets of emotion regulation. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J.M.; Jacobson, N.S.; Rushe, R.H.; Shortt, J.W.; Babcock, J.C.; LaTaillade, J.J.; Waltz, J. The relationship between heart rate reactivity, emotionally aggressive behavior, and general violence in batterers. J. Fam. Psychol. 1995, 9, 227248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock, J.C.; Green, C.E.; Webb, S.A.; Graham, K.H. A Second Failure to Replicate the Gottman et al. (1995) Typology of Men Who Abuse Intimate Partners ... and Possible Reasons Why. J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, J.C.; Holtzworth-Munroe, A.; Herron, K. Maritally violent men’s heart rate reactivity to marital interactions: A failure to replicate the Gottman et al. (1995) typology. J. Fam. Psychol. 2001, 15, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M.E.; Schell, A.M.; Filion, D.L. The electrodermal system. In Handbook of Psychophysiology, 2nd ed.; Cacioppo, J.T., Tassinary, L.G., Bernston, G.G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Martínez, A.; Moya-Albiol, L. Neuropsychology of perpetrators of domestic violence: The role of traumatic brain injury and alcohol abuse and/or dependence. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 57, 515–522. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Martinez, A.; Lila, M.; Moya-Albiol, L. Testosterone and attention deficits as possible mechanisms underlying impaired emotion recognition in intimate partner violence perpetrators. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. 2016, 8, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, A.; Lila, M.; Moya-Albiol, L. The 2D:4D Ratio as a Predictor of the Risk of Recidivism after Court-mandated Intervention Program for Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators. J. Forensic Sci. 2017, 62, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitoria-Estruch, S.; Romero-Martínez, A.; Ruiz-Robledillo, N.; Sariñana-González, P.; Lila, M.; Moya-Albiol, L. The Role of Mental Rigidity and Alcohol Consumption Interaction on Intimate Partner Violence: A Spanish Study. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2017, 26, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitoria-Estruch, S.; Romero-Martínez, A.; Lila, M.; Moya-Albiol, L. Differential cognitive profiles of intimate partner violence perpetrators based on alcohol consumption. Alcohol 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, A.A.; Giancola, P.R.; Morris, D.H.; Holt, J.C.D.; Gunn, R.L. Alcohol dose and aggression: Another reason why drinking more is a bad idea. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2011, 72, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, C.I.; Parrott, D.J.; Sprunger, J.G. Mechanisms of alcohol-facilitated intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women 2015, 21, 939–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, A.; Lila, M.; Catalá-Miñana, A.; Williams, R.K.; Moya-Albiol, L. The contribution of childhood parental rejection and early androgen exposure to impairments in socio-cognitive skills in intimate partner violence perpetrators with high alcohol consumption. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 3753–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, A.; Lila, M.; Moya-Albiol, L. Alcohol Abuse Mediates the Association between Baseline T/C Ratio and Anger Expression in Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators. Behav. Sci. 2015, 5, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, Á.; Lila, M.; Martínez, M.; Pedrón-Rico, V.; Moya-Albiol, L. Improvements in empathy and cognitive flexibility after court-mandated intervention program in intimate partner violence perpetrators: The role of alcohol abuse. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschloo, L.; Vogelzangs, N.; Licht, C.M.; Vreeburg, S.A.; Smit, J.H.; van den Brink, W.; Penninx, B.W. Heavy alcohol use, rather than alcohol dependence, is associated with dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011, 116, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, J.L.; Hiraoka, R.; McCanne, T.R.; Reo, G.; Wagner, M.F.; Krauss, A.; Skowronski, J.J. Heart rate and heart rate variability in parents at risk for child physical abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 2015, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpyak, V.M.; Romanowicz, M.; Schmidt, J.E.; Lewis, K.A.; Bostwick, J.M. Characteristics of Heart Rate Variability in Alcohol-Dependent Subjects and Nondependent Chronic Alcohol Users. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2014, 38, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S. Alcoholism and its Effects on the Central Nervous System. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 2013, 10, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chida, K.; Takasu, T.; Kawamura, H. Changes in sympathetic and parasympathetic function in alcoholic neuropathy. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 1998, 33, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chida, K.; Takasu, T.; Mori, N.; Tokunaga, K.; Komatsu, K.; Kawamura, H. Sympathetic dysfunction mediating cardiovascular regulation in alcoholic neuropathy. Funct. Neurol. 1994, 9, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Monforte, R.; Estruch, R.; Valls-Solé, J.; Nicolás, J.; Villalta, J.; Urbano-Marquez, A. Autonomic and peripheral neuropathies in patients with chronic alcoholism. A dose-related toxic effect of alcohol. Arch. Neurol. 1995, 52, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.F.; Porges, S.W.; Newlin, D.B. Effect of alcohol on vagal regulation of cardiovascular function: Contributions of the polyvagal theory to the psychophysiology of alcohol. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999, 7, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2001, 42, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalta, J.; Estruch, R.; Antúnez, E.; Valls, J.; Urbano-Márquez, A. Vagal neuropathy in chronic alcoholics: Relation to ethanol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol. 1989, 24, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, Á.; Moya-Albiol, L. Stress-Induced Endocrine and Immune Dysfunctions in Caregivers of People with Eating Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Martínez, Á.; Moya-Albiol, L. Reduced cardiovascular activation following chronic stress in caregivers of people with anorexia nervosa. Stress 2017, 20, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lila, M.; Gracia, E.; Herrero, J. Asunción de responsabilidad en hombres maltratadores: Influencia de la autoestima, la personalidad narcisista y la personalidad antisocial. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2012, 44, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lila, M.; Oliver, A.; Catalá-Miñana, A.; Conchell, R. Recidivism risk reduction assessment in batterer intervention programs: A key indicator for program efficacy evaluation. Psychosoc. Interv. 2014, 23, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lila, M.; Oliver, A.; Galiana, L.; Garcia, E. Predicting success indicators of an intervention programme for convicted intimate-partner violence offenders: The context programme. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. 2013, 5, 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Willett, W.C.; Rimm, E.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Giovannucci, E.L. Light to moderate intake of alcohol, drinking patterns, and risk of cancer: Results from two prospective US cohort studies. BMJ 2015, 351, h4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.; Lee, J.E.; Rimm, E.B.; Fuchs, C.S.; Giovannucci, E.L. Alcohol consumption and the risk of colon cancer by family history of colorectal cancer. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoccianti, C.; Cecchini, M.; Anderson, A.S.; Berrino, F.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Espina, C.; Wiseman, M. European Code against Cancer 4th Edition: Alcohol drinking and cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5ª), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R.A.; Brumm, V.; Zawacki, T.M.; Paul, R.; Sweet, L.; Rosenbaum, A. Impulsivity and verbal deficits associated with domestic violence. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2003, 9, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Geus, E.J.; Willemsen, G.H.; Klaver, C.H.; Van Doornen, L.J. Ambulatory measurement of respiratory sinus arrhythmia and respiration rate. Biol. Psychol. 1995, 41, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes del Paso, G.A.; Langewitz, W.; Mulder, L.J.M.; Van Roon, A.; Duschek, S. The utility of low frequency heart rate variability as an index of sympathetic cardiac tone: A review with emphasis on a reanalysis of previous studies. Psychophysiology 2013, 50, 47–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, M. Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 1996, 1, 151–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandín, B.; Chorot, P.; Lostao, L.; Joiner, T.E.; Santed, M.A.; Valiente, R.M. Escalas PANAS de afecto positivo y negativo: Validación factorial y convergencia transcultural. Psicothema 1999, 11, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, J.; Malloy, P. FrSBe, Frontal Systems Behavior Scale: Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Caracuel, A.; Verdejo-García, A.; Fernández-Serrano, M.J.; Moreno-López, L.; Santago-Ramajo, S.; Salinas-Sánchez, I.; Pérez-García, M. Preliminary validation of the Spanish version of the Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe) using Rasch analysis. Brain Injury 2012, 26, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutchik, R.; Van Pragg, H. The measurement of suicidality, aggressivity and impulsivity. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1989, 13, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcázar-Córcoles, M.A.; Verdejo, A.J.; Bouso-Sáiz, J.C. Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de impulsividad de Plutchik en una muestra de jóvenes hispanohablantes. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría 2015, 43, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, C.A.; Block, R.A.; Aguinis, H. Cautionary Note on Reporting Eta-Squared Values from Multifactor ANOVA Designs. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2004, 64, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruessner, J.C.; Kirschbaum, C.; Meinlschmid, G.; Hellhammer, D.H. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003, 28, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjörs, A.; Larsson, B.; Dahlman, J.; Falkmer, T.; Gerdle, B. Physiological responses to low-force work and psychosocial stress in women with chronic trapezius myalgia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsior, J.S.; Sacha, J.; Jeleń, P.J.; Zieliński, J.; Przybylski, J. Heart rate and respiratory rate influence on heart rate variability repeatability: Effects of the correction for the prevailing heart rate. Front Physiol. 2016, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijman, S.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Hiraoka, R.; Crouch, J.L.; Milner, J.S.; Alink, L.R.A.; van IJzendoorn, M.H. Baseline Functioning and Stress Reactivity in Maltreating Parents and At-Risk Adults: Review and Meta-Analyses of Autonomic Nervous System Studies. Child Maltreat. 2016, 21, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, S.; Hu, J.; Wu, P.L.; Chao, H.H.; Chiang-shan, R.L. Barratt impulsivity and neural regulation of physiological arousal. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, D.M.; Knoble, N.B.; Shortt, J.W.; Kim, H.K. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse 2012, 3, 231–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.A.; Sullivan, E.L.; Ronsebaum, A.; Wyngarden, N.; Umhau, J.C.; Miller, M.W.; Taft, C.T. Biological correlates of intimate partner violence perpetration. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2010, 15, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umhau, J.C.; George, D.T.; Reed, S.; Petrulis, S.G.; Rawlings, R.; Porges, S.W. Atypical autonomic regulation in perpetrators of violent domestic abuse. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambotti, M.; Willoughby, A.R.; Baker, F.C.; Sugarbaker, D.S.; Colrain, I.M. Cardiac autonomic function during sleep: Effects of alcohol dependence and evidence of partial recovery with abstinence. Alcohol 2015, 49, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, A.; Lila, M.; Moya-Albiol, L. The testosterone/cortisol ratio moderates the proneness to anger expression in antisocial and borderline intimate partner violence perpetrators. J. Forensic Psychiatr. Psychol. 2016, 27, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, Á.; Lila, M.; Moya-Albiol, L. Alcohol Abuse Mediates the Association between Baseline T/C Ratio and Anger Expression in Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators. Behav. Sci. 2015, 5, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajosa, P.; Català-Miñana, A.; Lila, M.; Gracia, E. Differences in treatment adherence, program completion, and recidivism among batterer subtypes. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. 2017, 9, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, A.; Ruiz-Robledillo, N.; Sariñana-González, P.; de Andrés-García, S.; Vitoria-Estruch, S.; Moya-Albiol, L. A cognitive-behavioural intervention improves cognition in caregivers of people with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. Psychosoc. Interv. 2017, 26, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, Á.; Lila, M.; Gracia, E.; Moya-Albiol, L. Improving empathy with motivational strategies in batterer intervention programmes: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lila, M.; Gracia, E.; Catalá-Miñana, A. Individualized motivational plans in batterer intervention programs: A randomized clinical trial. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 2018, 86, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | IPV Perpetrators | Control (n = 35) | ηp2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Alcohol | Low Alcohol | |||

| (n = 27) | (n = 33) | |||

| Age (years) | 40.07 ± 12.10 | 39.84 ± 10.09 | 42.14 ± 10.94 | 0.080 |

| Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) | 22.44 ± 3.80 | 24.15 ± 3.41 | 24.46 ± 4.74 | 0.043 |

| Nationality | 0.079 | |||

| Spanish | 22 (81.48%) | 26 (78.78%) | 28 (80%) | |

| Latin Americans | 3 (11.11%) | 3 (9.09%) | 5 (14.26%) | |

| Africans | 2 (7.41%) | 4 (12.13%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Marital status | 0.086 | |||

| Single | 10 (37.03%) | 11 (33.33%) | 16 (45.71%) | |

| Married | 5 (18.52%) | 9 (27.28%) | 14 (40.00%) | |

| Separate/Divorced/Widowed | 12 (44.45%) | 13 (39.39%) | 5 (14.28%) | |

| Number of children | 0.80 ± 1.30 | 1.67 ± 2.08 | 0.86 ± 0.97 | 0.048 |

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary/lower secondary | 20 (70.07%) | 16 (48.48%) | 14 (40%) | |

| Upper secondary/vocational training | 6 (22.22%) | 15 (45.45%) | 18 (51.43%) | |

| University | 1 (2.70%) | 2 (6.07%) | 3 (8.57%) | |

| Employment status | 0.065 | |||

| Employed | 12 (44.50%) | 14 (43.75%) | 15 (42.86%) | |

| Unemployed | 15 (55.50%) | 19 (59.37%) | 20 (57.14%) | |

| Income level | 0.063 | |||

| 1800 €–12,000 € | 14 (51.86%) | 13 (39.39%) | 21 (60%) | |

| >12,000 €–30,000 € | 12 (44.44%) | 16 (48.49%) | 12 (34.28%) | |

| >30,000 €–90,000 € | 1 (3.70%) | 4 (12.12%) | 2 (5.72%) | |

| Age at start of alcohol consumption | 16.35 ± 2.16 | 18.10 ± 5.16 | 17.06 ± 3.02 | 0.035 |

| Amount of alcohol consumption per day 1,* | 64.65 ± 8.32 | 9.41 ± 11.15 | 6.23 ± 7.90 | 0.260 |

| Time of alcohol abstinence (months) | 0.34 ± 0.79 | 1.44 ± 3.40 | 0.69 ± 3.35 | 0.080 |

| Cigarettes/day | 11.74 ± 9.04 | 12.76 ± 10.84 | 8 ± 6.41 | 0.046 |

| Fagerström test | 3.94 ± 2.10 | 4.31 ± 3.59 | 3.36 ± 2.76 | 0.670 |

| Criminal records other than IPV | 0.87 | |||

| No | 28 (84.85%) | 21 (84%) | - | |

| Yes | 1 (3.03%) | 0 (0%) | - | |

| Yes, but no violence | 4 (12.12%) | 4 (16%) | - | |

| Time of sentencing (months) | 9.81 ± 6.52 | 11.90 ± 8.89 | - | 0.93 |

| Variable | IPV Perpetrators | Low Alcohol (n = 33) | Control (n = 35) | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Alcohol | ||||

| (n = 27) | ||||

| PANAS Positive affect 1,* | ||||

| Pre | 29.22 ± 8.88 | 29.61 ± 6.76 | 28.89 ± 7.45 | 0.125 |

| Post | 25.81 ± 9.35 | 26.03 ± 8.53 | 28.69 ± 8.01 | 0.710 |

| Negative affect 1 | ||||

| Pre | 13.59 ± 3.51 | 12.70 ± 3.07 | 12.43 ± 2.33 | 0.095 |

| Post | 12.19 ± 2.74 | 12.06 ± 2.79 | 11.43 ± 2.52 | 0.125 |

| Appraisal | ||||

| Satisfaction 2 | 6.37 ± 1.20 | 6.57 ± 1.46 | 8.06 ± 1.11 | 0.270 |

| Internal locus of control 2 | 7.22 ± 1.62 | 7.19 ± 1.62 | 8.11 ± 0.96 | 0.126 |

| External locus of control 2 | 2.78 ± 1.62 | 2.81 ± 1.19 | 1.89 ± 0.96 | 0.126 |

| Cooperation 2 | 4 ± 0.69 | 4.17 ± 0.65 | 4.57 ± 0.60 | 0.125 |

| Frustration tolerance 2 | 3.05 ± 0.86 | 3.31 ± 0.76 | 3.89 ± 0.58 | 0.219 |

| Frontal System Behavior Scale | ||||

| Executive dysfunction 3 | 43.42 ± 10.51 | 36.57 ± 8.11 | 37.81 ± 7.72 | 0.086 |

| Disinhibition 3 | 41.79 ± 11.96 | 35.27 ± 9.85 | 34.34 ± 7.14 | 0.086 |

| Impulsivity Scale | ||||

| Self-Control | 5.30 ± 2.90 | 4.27 ± 2.94 | 5.88 ± 2.88 | 0.234 |

| Planning deficits 3 | 8.74 ± 1.94 | 8.28 ± 2.15 | 5.54 ± 2.63 | 0.241 |

| Physiological behaviors control 3 | 0.63 ± 0.92 | 0.79 ± 1.11 | 1.30 ± 0.91 | 0.086 |

| Spontaneous attitude | 3.19 ± 1.38 | 2.82 ± 1.86 | 3 ± 1.87 | 0.655 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vitoria-Estruch, S.; Romero-Martínez, Á.; Lila, M.; Moya-Albiol, L. Could Alcohol Abuse Drive Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators’ Psychophysiological Response to Acute Stress? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122729

Vitoria-Estruch S, Romero-Martínez Á, Lila M, Moya-Albiol L. Could Alcohol Abuse Drive Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators’ Psychophysiological Response to Acute Stress? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(12):2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122729

Chicago/Turabian StyleVitoria-Estruch, Sara, Ángel Romero-Martínez, Marisol Lila, and Luis Moya-Albiol. 2018. "Could Alcohol Abuse Drive Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators’ Psychophysiological Response to Acute Stress?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 12: 2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122729

APA StyleVitoria-Estruch, S., Romero-Martínez, Á., Lila, M., & Moya-Albiol, L. (2018). Could Alcohol Abuse Drive Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators’ Psychophysiological Response to Acute Stress? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(12), 2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122729