Assessment of Patient and Occupational Safety Culture in Hospitals: Development of a Questionnaire with Comparable Dimensions and Results of a Feasibility Study in a German University Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim of the Study

- -

- standard deviation of the outcome measure, which is needed in some cases to estimate sample size,

- -

- willingness of participants to be randomised,

- -

- willingness of clinicians to recruit participants,

- -

- number of eligible patients,

- -

- characteristics of the proposed outcome measure, and in some cases feasibility studies might involve designing a suitable outcome measure, and

- -

- follow-up rates and response rates to questionnaires, adherence/compliance rates, ICCs in cluster trials, etc.

- -

- feasibility of the survey in nurses and physicians at the same time, number of eligible participants,

- -

- response rate and respective influencing factors (“profession”, “surgical vs. non-surgical department”, and experts´ rated safety quality of the department as “low/medium/or high”),

- -

- time needed to collect and analyse the data,

- -

- internal scale consistency and content validity (where applicable), and

- -

- descriptive measures of outcomes: perceived patient safety and occupational safety culture, perceived individual occupational risk and prevention, knowledge and competencies in patient safety (exemplified by the prevention of nosocomial infections in patients) and in occupational safety (exemplified by the prevention of viral infections of employees).

2.2. Design, Setting and Participants

2.3. Questionnaire

- -

- Patient Safety Culture (PSC): Six dimensions from the German version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSPSC) [30] were used (Table 1, dimensions nos. 1–6, slightly modified according to the German version of the questionnaire in the High 5s project [13]). Hereby HSPSC scales covering aspects that belong to the dimensions of psychosocial working conditions (e.g., scale “staffing”) were omitted in favour of generic scales derived from the questionnaire COPSOQ (e.g., scale “quantitative demands”; see below). The scale “Frequencies of events reported” (Table 1, dimension no. 7) was modified and reconstructed using own items. Two global items derived from the German Questionnaire Working Conditions in Hospitals (ArbiK) covered the general assessment of patient safety culture at the workplace and satisfaction with work processes (Table 1, dimensions nos. 8–9) [31]. All scales were operationalized following the HSPSC scheme used in the High 5s study [12,13]: Items were defined based on the five-point Likert response scale of agreement (from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”), or of frequency (from “always “ to “never “). For analysis, in the case of positive worded scale dimensions, we reversely coded negative worded items. Then, all answers on the five-point Likert scale were dichotomised into 0 and 1 (e.g., strongly/partly disagree, undecided vs. partly/strongly agree). In a third step, we constructed a sum score divided by the number of items. Results multiplied by 100 lead to the percentage of positive response to the dimension.

- -

- “Twins”—Patient safety culture (PSC)/Occupational safety culture (OSC): Based on the German version of the HSPSC and the German version of the questionnaire Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (FTPS) [32], we used nine “twin”-items to analogously assess the role of hospital management and of the direct supervisor as well as the aspect of organisational learning for patient safety culture and occupational safety culture. By doing so, we acknowledged the specific importance of leadership and organisational aspects for both patient safety and occupational safety, as described in literature (e.g., refs. [33,34] for occupational safety, [35,36,37] for different aspects of both, patient and occupational safety). Items from four HSPSC scales address the direct supervisor, organisational learning, and hospital management (Table 1, dimensions nos. 15–18). Three self-constructed single items covered the perceived attitude of the direct supervisor towards PSC or OSC (Table 1, dimension no. 19, and dimensions nos. 20–21 adopted from the German version of the questionnaire Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (FTPS) [32]). One item addressed the individual’s influence on PSC and OSC at the workplace (Table 1, dimension no. 22) and another item covered a general assessment of PSC and OSC at the workplace (Table 1, no. 23). Here, items were also defined based on the 5-point Likert response scale of agreement (from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”, “very vast extent” to “very small extent”, and “excellent” to “insufficient, respectively). For the statistical analysis of PSC, OSC and “twins”, negatively worded items were reversed prior to calculating the scale. Agreement was determined within the relevant dimensions and was transferred to a standardised sum score, interpreted as “mean percent of agreement”.

- -

- Occupational safety perceptions (individual occupational risk and prevention): Five self-constructed scales covered the employees´ personal perceptions of occupational risks and their responses to hazardous work situations, their attitudes towards occupational safety rules, as well as safety measures on the individual and organizational levels (Table 1, dimensions nos. 10–14). The items were developed based on a previously conducted literature review. Items were also defined based on the five-point Likert response scale of frequency (from “always” to “never”) or of agreement (from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”, “very important” to “very unimportant”, and “very vast extent” to “very small extent”, respectively).

- -

- Knowledge/competencies regarding patient safety and occupational safety

- ο

- Patient safety (PS): Regarding patient safety, we assessed the knowledge and handling of bladder catheters following the in-house guideline of the hospital, which was updated and communicated before the survey was executed in 2012. Multiple choice questions were developed based on the content of the hospital´s guideline, depicting the two dimensions knowledge and competency: Knowledge about appropriate measures to avoid bladder catheter-associated infections (Table 2, dimension PS-know), and competency to detect and treat infections of patients with indwelling bladder catheters (Table 2, dimension PS-comp). The results of the multiple choice questions were summarised as “number of appropriate answers” score.

- ο

- Occupational safety (OS): Regarding occupational safety, all questions concerning the following three dimensions were derived from the German project STOP Needlestick [37]:

- ▪

- knowledge about post-exposure prophylaxis in the case of exposure to Hepatitis B or C virus or HIV (Table 2, dimension OS-know),

- ▪

- competency for appropriate behaviour in the case of a needlestick injury (Table 2, dimension OS-comp), and

- ▪

- subjective information status to handle a needlestick injury appropriately (Table 2, dimension OS-info),

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Treatment of Missing Data and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility, Number of Eligible Participants and Response Rates

3.2. Time Needed to Collect and Analyse the Data

3.3. Internal Scale Consistency and Content Validity of Scales and Expert Ratings

- -

- between OS knowledge and “Organisational learning–continuous improvement of OS” and “Hospital management’s support for OS” (nos. 17 and 18 in Table 1; both rho = 0.13, p = 0.003), and

- -

- between OS competencies and “Direct supervisor’s expectations and actions promoting occupational safety” (nos. 15; rho = 0.13, p = 0.003).

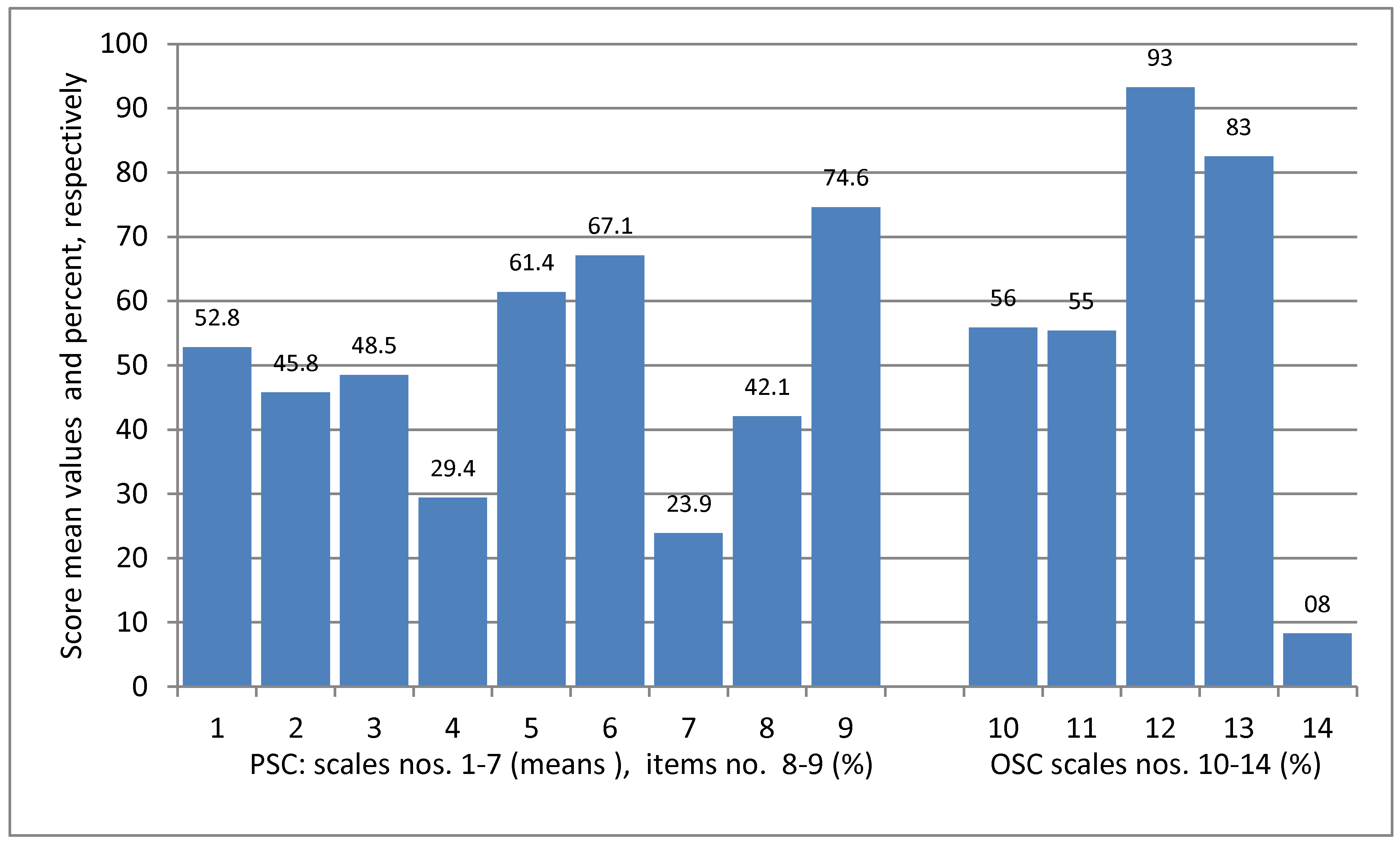

3.4. Perceived Patient Safety Culture (PSC)

- (1)

- Non-punitive response to error (SD 37.2)

- (2)

- Overall perceptions of safety (SD 35.7)

- (3)

- Hospital handoffs and transitions (SD 32.4)

- (4)

- Feedback and communication about errors (SD 28.1)

- (5)

- Communication openness (SD 36.3)

- (6)

- Teamwork within units (SD 34.9)

- (7)

- Frequencies of events reported (SD 24.6)

- (8)

- Satisfaction with work processes (global item)

- (9)

- Trustworthiness of work unit (global item)

- (10)

- Personal perception of the frequency of occupational risks (SD 28.6)

- (11)

- Attitudes towards occupational safety rules (SD 26.5)

- (12)

- Subjective assessment of occupational safety measures initiated by the employer, related to own safety (SD 15.8)

- (13)

- Subjective assessment of specific protective measures (behaviour and regulations) related to infectious diseases (SD 20.4)

- (14)

- Frequency of contact to responsible specialist /official after hazardous work situations (SD 14.8)

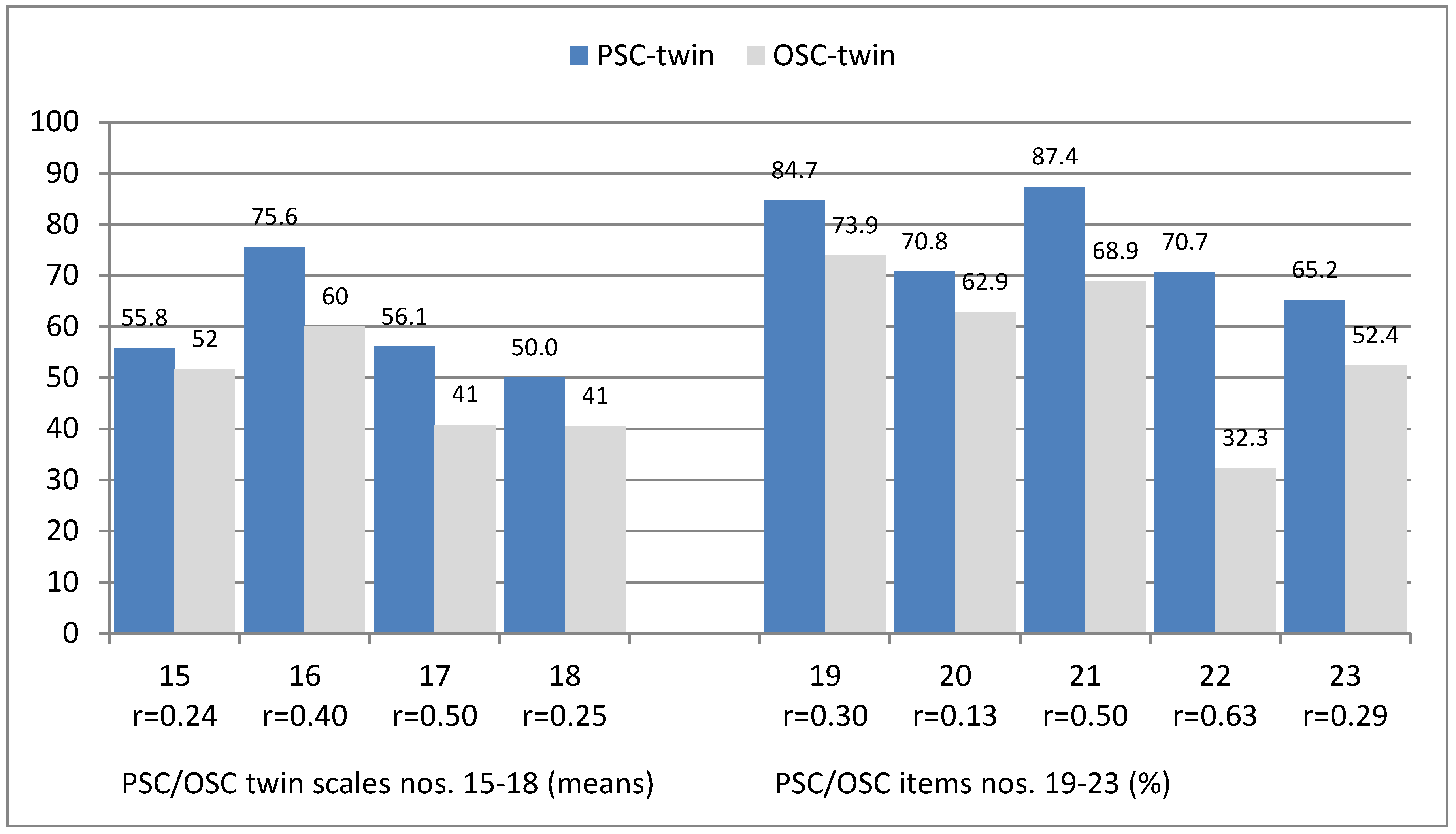

- (15)

- Direct supervisor’s expectations and actions promoting safety (28.4/30.3)

- (16)

- Direct supervisors’ support for PSC/OSC (33.4/37.8)

- (17)

- Organisational learning–continuous improvement of PSC/OSC (36.7/36.6)

- (18)

- Hospital managements’ support for PSC/OSC (40.7/40.4)

- (19)

- Direct supervisor’s addressing of problems related to PS/OS- aspects

- (20)

- (Direct supervisor’s increased focus on PSC/OSC

- (21)

- Direct supervisors’ attention to PSC/OSC

- (22)

- Individual influence on PSC/OSC at the workplace

- (23)

- General assessment of PS/OS at the workplace (global item; excellent/very good)

3.5. Perceived Occupational Safety Culture (OSC)

3.6. Occupational Safety Perceptions (Individual Occupational Risk and Prevention)

3.7. Knowledge and Competencies about Patient and Occupational Safety

3.8. Statistical Comparisons Between Occupational Safety and Patient Safety

4. Discussion

4.1. Feasibility, Number of Eligible Participants and Response Rate

4.2. Internal Scale Consistency and Content Validity of Scales and Expert Ratings

4.3 Perceived Patient Safety Culture (PSC)

4.4. Perceived Occupational Safety Culture (OSC)

4.5. Occupational Safety Perceptions (Individual Occupational Risk and Prevention)

4.6 Knowledge and Competencies about Patient Safety (PS) and Occupational Safety (OS)

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- -

- how such a study could be performed well (including sampling and recruitment strategy, sample size calculation, and non-responder analysis),

- -

- the development and evaluation of measurement tools for the simultaneous assessment of patient safety culture and occupational safety culture, and

- -

- the investigation of patient-related outcomes in conjunction with both patient safety and occupational safety cultures in a larger sample in order to describe relevant predictors.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Health & Safety Commission. ACSNI Human Factors Study Group Third Report: Organising for Safety; HMSO: London, UK, 1993.

- Wagner, C.; Mannion, R.; Hammer, A.; Groenes, O.; Arah, O.A.; Dersarkissian, M.; Sunol, R.; Duque Project Consortium. The associations between organizational culture, organizational structure and quality management in European hospitals. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2014, 26, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorra, J.; Nieva, V.F. Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture; AHRQ Publication No. 04-0041: Rockville, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S.; Seto, K.; Kigawa, M.; Fujita, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Hasegawa, T. Development and applicability of Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPS) in Japan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Y.; Mao, X.; Cui, H.; He, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, M. Hospital survey on patient safety culture in China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghri, J.; Arab, M.; Saari, A.A.; Nategi, E.; Forooshani, A.R.; Ghiasvand, H.; Sohrabi, R.; Goudarzi, R. The Psychometric Properties of the Farsi Version of “Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture” in Iran’s Hospitals. Iran. J. Public Health 2012, 41, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bodur, S.; Filiz, E. Validity and reliability of Turkish version of “Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture” and perception of patient safety in public hospitals in Turkey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, M.; Christiaans-Dingelhoff, I.; Wagner, C.; Wal, G.; Groenewegen, P.P. The psychometric properties of the ‘Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture’ in Dutch hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugen, A.S.; Softeland, E.; Eide, G.E.; Nortvedt, M.W.; Aase, K.; Harthug, S. Patient safety in surgical environments: Cross-countries comparison of psychometric properties and results of the Norwegian version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, S.; Seto, K.; Kigawa, M.; Fujita, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Hasegawa, T. The characteristics of patient safety culture in Japan, Taiwan and the United States. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, A.; Ernstmann, N.; Ommen, O.; Wirtz, M.; Manser, T.; Pfeiffer, Y.; Pfaff, H. Psychometric properties of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture for hospital management (HSOPS_M). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Action on patient safety—High 5s. 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/solutions/high5s/High5_overview.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- WHO. Internationales High 5s-Projekt Patient Safety Initiative. Mitarbeiterbefragung zur Sicherheitskultur im Krankenhaus. Ergebnisbericht [International High 5s- project Patient Safety Initiative. Employee survey related to patient safety culture in hospitals. Report to World Health Organization] (unpublished), Germany 2011.

- Letvak, S.A.; Ruhm, C.J.; Gupta, S.N. Nurses’ presenteeism and its effects on self-reported quality of care and costs. Am. J. Nurs. 2012, 112, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimura, M.; Imai, M.; Okawa, M.; Fujimura, T.; Yamada, N. Sleep, mental health status, and medical errors among hospital nurses in Japan. Ind. Health 2010, 48, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, K.; Shields, M. Correlates of medication error in hospitals article. Health Rep. 2008, 19, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K.; Grebner, S. Work stress and patient safety: Observer-rated work stressors as predictors of characteristics of safety-related events reported by young nurses. Ergonomics 2006, 49, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.H.; Clarke, S.P.; Sloane, D.M.; Sochalski, J.; Silber, J.H. Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Mortality, Nurse Burnout, and Job Dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002, 288, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, P.D.; Weaver, M.D.; Frank, R.C.; Warner, C.W.; Martin-Gill, C.; Guyette, F.X.; Fairbanks, R.J.; Hubble, M.W.; Songer, T.J.; Callaway, C.W.; et al. Association between poor sleep, fatigue, and safety outcomes in emergency medical services providers. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2012, 16, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahrenkopf, A.M.; Sectish, T.C.; Barger, L.K.; Sharek, P.J.; Lewin, D.; Chiang, V.W.; Edwards, S.; Wiedermann, B.L.; Landrigan, C.P. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008, 7642, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gander, P.H.; Merry, A.; Millar, M.; Weller, J. Hours of work and fatigue-related error: A survey of New Zealand anaesthetists. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2000, 28, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loerbroks, A.; Weigl, M.; Li, J.; Angerer, P. Effort-reward imbalance and perceived quality of patient care: A cross-sectional study among physicians in Germany. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer, T.; Schneider, A.; Spieß, E.; Angerer, P.; Weigl, M. Associations between job demands, work-related strain and perceived quality of care: A longitudinal study among hospital physicians. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2016, 28, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, B.A.; Hughes, L.C.; Belyea, M.; Chang, Y.; Hoffmann, D.; Jones, C.B.; Bacon, C.T. Does safety climate moderate the influence of staffing adequacy and work conditions on nurse injuries? Saf. Res. 2007, 38, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Mark, B. An Investigation of the relationship between safety climate and medication errors as well as other nurse and patient outcomes. Pers Psychol. 2006, 59, 847–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.A.; Dominici, F.; Agnew, J.; Gerwin, D.; Morlock, L.; Miller, M.R. Do nurse and patient injuries share common antecedents? An analysis of associations with safety climate and working conditions. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2012, 21, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Wakefield, B.J.; Wakefield, D.S.; Cooper, L.B. Nurse burnout and patient safety outcomes: Nurse safety perception versus reporting behavior. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2008, 30, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pousette, A.; Larsman, P.; Eklöf, M.; Törner, M. The relationship between patient safety climate and occupational safety climate in healthcare—A multi-level investigation. J. Saf. Res. 2017, 61, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arain, M.; Campbell, M.J.; Cooper, C.L.; Lancaster, G.A. What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, Y.; Manser, T. Development of the German version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: Dimensionality and psychometric properties. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 1452–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomeyczik, S.; Donath, E.; Schmidt, S.; Rieger, M.A.; Berger, E.; Wittich, A.; Dieterle, W.E. Arbeitsbedingungen im Krankenhaus: Abschlussbericht F2032; Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin: Dortmund/Berlin/Dresden, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, I.; Renner, W.; Schwarz, N. Der Fragebogen zu Teamwork und Patientensicherheit–FTPS. Praxis Klinische Verhaltensmedizin und Rehabilitation 2008, 79, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- MacDavitt, K.; Chou, S.S.; Stone, P.W. Organizational climate and health care outcomes. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2007, 33, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Barling, J. Leadership development as an intervention in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 2010, 24, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassi, A.; Hancock, T. Patient safety—Worker safety: Building a culture of safety to improve healthcare worker and patient well-being. Healthc. Q. 2005, 8, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squires, M.; Tourangeau, A.; Spence Laschinger, H.K.; Doran, D. The link between leadership and safety outcomes in hospitals. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, M.A.; Kempe, K.; Strahwald, B. Einführung Sicherer Instrumente und Spritzensysteme zur Prävention von Schnitt- und Nadelstichverletzungen. 2008. Available online: https://www.inqa.de/SharedDocs/PDFs/DE/Handlungshilfen/Handlungshilfe-Stop-Abschlussbericht.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Nübling, M.; Stößel, U.; Hasselhorn, H.; Michaelis, M.; Hofmann, F. Measuring Psychological Stress and Strain at Work: Evaluation of the COPSOQ Questionnaire in Germany. Available online: http://www.egms.de/static/en/journals/psm/2006-3/psm000025.shtml (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; Mc Graw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, C.J. An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwappach, D.L. When silence is dangerous: “Speaking-up” about safety concerns. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen 2016, 114, 5–12. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuss, I.; Nübling, M.; Hasselhorn, H.M.; Schwappach, D.; Rieger, M.A. Working conditions and Work-Family Conflict in German hospital physicians: Psychosocial and organisational predictors and consequences. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, C.; Ommen, O.; Driller, E.; Ernstmann, N.; Wirtz, M.A.; Köhler, T.; Pfaff, H. Burnout in nurses—The relationship between social capital in hospitals and emotional exhaustion. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 1654–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perneger, T.V.; Staines, A.; Kundig, F. Internal consistency, factor structure and construct validity of the French version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2014, 23, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, A.; Manser, T. The Use of the Hospital Survey of Patient Safety Culture in Europe; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, C.; Flin, R.; Mearns, K. Patient safety climate and worker safety behaviours in acute hospitals in Scotland. J. Saf. Res. 2013, 45, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, C.; Smits, M.; Sorra, J.; Huang, C. Assessing patient safety culture in hospitals across countries. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2013, 25, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeek-van Noord, I.; Wagner, C.; Dyck, C.; Twisk, J.R.; De Bruijne, M.C. Is culture associated with patient safety in the emergency department? A study of staff perspectives. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2014, 26, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger-Brand, E.; Richter-Kuhlmann, E. Patientensicherheit: Viel erreicht—Viel zu tun. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2014, 111, 628–632. [Google Scholar]

- Prüss-Ustün, A.; Rapiti, E.; Hutin, Y. Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2005, 48, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goniewicz, M.; Wloszczak-Szubzda, A.; Niemcewicz, M.; Witt, M.; Marciniak-Niemcewicz, A.; Jerzy Jarosz, M. Injuries caused by sharp instruments among health care workers—International and Polish perspectives. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2012, 3, 523–527. [Google Scholar]

- Gestal, J.J. Occupational hazards in hospitals: Accidents, radiation, exposure to noxious chemicals, drug addiction and psychic problems, and assault. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1987, 44, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicker, S.; Jung, J.; Allwinn, R.; Gottschalk, R.; Rabenau, H. Prevalence and prevention of needlestick injuries among health care workers in a German university hospital. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2008, 81, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Motavaf, M.; Dolotabadi, M.R.M.; Ghodraty, M.R.; Siamdoust, S.A.S.; Safari, S.; Mohseni, M. Anesthesia Personnel’s Knowledge of, Attitudes Toward, and Practice to Prevent Needlestick Injuries. Workplace Health Saf. 2014, 62, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, M.B.; Hannon, M.J.; Cagney, D.; Harrington, U.; O’Brien, F.; Hardiman, N.; O’Connor, R.; Courtney, K.; O’Connor, C. A study of needle stick injuries among non-consultant hospital doctors in Ireland. J. Med. Sci. 2011, 180, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toennessen, B.; Swart, E.; Marx, Y. Patientensicherheitskultur—Wissen und Wissensbedarf bei Medizinstudierenden. Zentralblatt für Chirurgie 2013, 138, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, B. Das Aktionsbündnis Patientensicherheit: Erreichtes, aktuelle und zukünftige Her-ausforderungen. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung 2013, 8, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinschmidt, M.; Michaelis, M.; Drössler, S.; Girbig, M.; Berger, I.; Dröge, P. Praxislernort Pflege: Anleiten zu einer demografiefesten Pflegepraxis (DemoPrax Pflege). 2015. Available online: https://www.inqa.de/SharedDocs/PDFs/DE/Projekte/praxislernort-demo-prax-pflege-abschlussbericht.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Hölscher, U.M.; Gausmann, P.; Haindl, H.; Heidecke, C.; Hübner, N.; Lauer, W. Review: Patient safety as a national health goal: Current state and essential fields of action for the German healthcare system. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen 2014, 108, 6–14. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Haines, A.; Kinmonth, A.L.; Sandercock, P.; Spiegelhalter, D.; Tyrer, P. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ 2000, 321, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, A.; Hammer, A.; Manser, T.; Martus, P.; Sturm, H.; Rieger, M.A. Do Occupational and patient safety culture in hospitals share predictors in the field of psychosocial working conditions? Findings from a cross-sectional study in German university hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Dimensions | Items | Response Categories | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Safety Culture (PSC) | ||||

| 1 | Non-punitive response to error | Please assess your unit: | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1.Staff feel like their mistakes are held against them 2. When an event is reported, it feels like the person is being written up, not the problem 3. Staff worry that mistakes they make are kept in their personnel file | ||||

| 2 | Overall perceptions of safety | Please assess your unit: | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1. Patient safety is never is never sacrificed to get more work done 2. It is just by chance that more serious mistakes don’t happen around here 3. We have patient safety problems in this unit 4. Our procedures and systems are good at preventing errors from happening | ||||

| 3 | Hospital handoffs and transitions | Please indicate to what extent you agree with the following statements about your unit: | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1. Things “fall between the cracks” when transferring patients from one unit to another 2. Important patient care information is often lost during shift changes 3. Problems often occur in the exchange of information across hospital units 4. Shift changes are problematic for patients in this hospital | ||||

| 4 | Feedback and communication about errors (organizational learning) | How often do you encounter the following situations in your unit? | Always—often—sometimes—seldom–never | HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1. We are given feedback about changes put into place based on event reports 2. In this unit, we discuss ways to prevent errors from happening again 3. We are informed about errors that happen in this unit | ||||

| 5 | Communication openness (organizational learning) | How often do you encounter the following situations in your unit? | Always—often—sometimes—seldom–never | HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1. Staff feel free to question the decisions or actions of those with more authority 2. Staff will freely speak up if they see something that may negatively affect patient care 3. Staff are afraid to ask questions when something does not seem right | ||||

| 6 | Teamwork within units | Please assess your unit: | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1. People support one another in this unit 2. When one area in this unit gets really busy, others help out 3. When a lot of work needs to be done quickly, we work together as a team to get the work done 4. In this unit, people treat each other with respect | ||||

| 7 | Frequencies of events reported | If a critical incident (e.g., a near-mistake) occurs in your unit—how often is it reported as critical incident... | Always—often—sometimes—seldom–never | Adapted from HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1. if it (e.g., a mistake) is noticed and corrected before the patient is affected? 2. if it (e.g., a mistake) occurs which could potentially harm the patient, but does not? 3. if it (e.g., a mistake) occurs which harms the patient? | ||||

| 8 | Satisfaction with work processes (global item) | I am very satisfied with the way work processes are organized in our unit | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | ArbIK |

| 9 | Trustworthiness of work unit (global item) | Without any reservations, I can recommend our unit to potential patients | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | ArbIK |

| Occupational Safety Culture (OSC) | ||||

| 10 | Personal perception of the frequency of occupational risks | 1. How often does a situation, which is hazardous for you, occur in your hospital? 2. Do you feel exposed to hazards of infection? 3. Do you feel exposed to hazards of skin disease? 4. Do you feel exposed to serious consequences of extended work shifts? 5. Do you feel exposed to hazardous substances? | Always—often—sometimes—seldom–never | Self-constructed item(s) |

| 11 | Attitudes towards occupational safety rules | How much do you value the following measures concerning your own safety and health at work? | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | Self -constructed item(s) |

| 1. The adherence to work safety regulations should be controlled more rigidly 2. Violations of work safety regulations should lead to clear consequences 3. Work safety regulations make work in hospitals safer 4. Work safety regulations can sometimes be constricting | ||||

| 12 | Subjective assessment of occupational safety measures initiated by the employer, related to own safety | How much do you value the following measures concerning your own safety and health at work in the hospital: | Very important –important—partly—unimportant—very unimportant | Self -constructed item(s) |

| 1. regulations on how to act in the case of fire or other emergency, 2. escape and emergency exits, 3. procedures after a work accident, 4. first aid organization, 5. work time/shift regulations, 6. instruction on workplace related hazards and first aid | ||||

| 13 | Subjective assessment of specific protective measures (behaviour and regulations) related to infectious diseases | Protective measures and procedures are meant to reduce risks, e.g., infections. Do you believe this is provided by | Very vast extend–vast extent—party—small extend—very small extend | Self -constructed item(s) |

| 1. protective gloves, 2. protective clothing, 3. respiratory protective masks, 4. container for needle disposal (sharps container), 5. hygiene instruction, 6. maternity protection regulations, 7. hand and surface disinfection | ||||

| 14 | Frequency of contact to responsible specialist /offical after hazardous work situations | In the case of an occurrence of work related health hazards, how often did you contact | Always—often—sometimes—seldom–never | Self -constructed item(s) |

| 1. your supervisor, 2. a specialist for work safety, 3. the safety delegate of your unit, 4. a member of the staff council, 5. a hygiene specialist, 6. a company doctor, 7. an external institution /office | ||||

| “Twins”–Patient/Occupational Safety Culture | ||||

| 15 | Direct supervisor’s expectations and actions promoting safety (PS/OS) * | Please indicate to what extent you agree with the following statements about your direct supervisor: | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1. My direct supervisor says a good word words when he sees that a task is done in accordance with established rules (standards and guidelines) 2. Whenever pressure builds up, my supervisor wants us to work faster 3. My direct supervisor seriously considers staff suggestions for improving PS/OS safety 4. My direct supervisor overlooks PS/OS safety problems that happen over and over | ||||

| 16 | Direct supervisors’ support for PS/OS * | Please indicate to what extend you agree with the following statements about your direct supervisor: | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | Adapted from HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1. My direct supervisor provides a work climate that promotes PS/OS 2. The actions of my direct supervisor show that PS/OS is a top priority 3. My direct supervisor seems not interested in patient safety only after an adverse event happens | ||||

| 17 | Organisational learning–continuous improvement of PS/OS * | Please assess your unit: | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1. Mistakes have led to positive changes here 2. After we make changes to improve patient safety, we evaluate their effectiveness 3. We are actively doing things to improve patient safety PS/OS | ||||

| 18 | Hospital management’s support for PS/OS* | Please indicate to what extent you agree with the following statements about your hospital: | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | HSPSC (High 5s) |

| 1. The hospital management provides a work climate that promotes PS/OS 2. The actions of the hospital management show that of patient safety is top priority 3. The hospital seems interested in patient safety only after an adverse event happens | ||||

| 19 | Direct supervisor’s addressing of problems related to PS/OS- aspects * | My direct supervisor openly addresses problems concerning PS/OS in our hospital | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | Self-constructed item(s) |

| 20 | Direct supervisors’ increased focus on PS/OS * | My direct supervisor focuses more on PS/OS than a year ago | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | Adapted from FTPS |

| 21 | Direct supervisor’s attention to PS/OS * | It is important to my direct supervisor that our hospital pays great attention to PS/OS | Strongly/partly agree–undecided–partly/strongly disagree | Adapted from FTPS |

| 22 | Individual influence on PS/OS at the workplace * | Do you have an individual influence on how well PS/OS is implemented at the workplace? | Very vast extend–vast extent—party—small extend—very small extend | Self-constructed item(s) |

| 23 | General assessment of PS/OS at the workplace (global item) * | How would you evaluate the overall PS/OS in your unit? | Excellent–very good—acceptable—inadequate–insufficient | Self-constructed item(s) |

| No. (Acronym) | Dimension | Items | Possible Range | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Safety: Knowledge/Competencies | ||||

| 1 (PS-know) (score) | Knowledge about appropriate measures to avoid bladder catheter associated infections (multiple choice) | Which measures are appropriate to avoid catheter-acquired urinary tract infections in patients with indwelling catheters? | 0–6 items appropriately answered | Self-constructed item(s) |

| 1. Indwelling urinary catheters should routinely be exchanged in strict intervals. (false) 2. Before an indwelling transurethral catheter is removed, it should intermittently be blocked by means of a clamp (so called “bladder-training”). (false) 3. The urine bag must hang freely without touching the floor and must be positioned lower than the patient’s bladder. (right) 4. Before working on the drainage system of the indwelling transurethral catheter, a hygienic and disinfection is necessary. (right) 5. Upon placing a long-term transurethral catheter, infection prophylaxis with an antibiotic is usually not necessary. (right) 6. During urine disposal, it is no problem if the drainage tap touches the receptacle. (false) | ||||

| 2 (PS-comp) (score) | Competency to detect and treat infections of patients with indwelling bladder catheters (multiple choice) | In patients with indwelling transurethral catheters, it is particularly important to detect an infection and immediately start therapy. How is this accomplished? | 0–3 items appropriately answered | Adapted from project STOP Needlestick |

| 1. Regular routine screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria. (right) 2. Bacteriuria screening indicated by clinical symptoms. (right) 3. Bladder wash-outs and insertion of fluids into the catheter as a means for infection prophylaxis. (false) | ||||

| Occupational safety: Knowledge/competencies | ||||

| 3 (OS-know) (scale) | Knowledge about post-exposure prophylaxis of Hepatitis-B- and C-virus and HIV (multiple choice) | After a needlestick injury, certain medications can prevent infection. For which infectious diseases is this an option? | 0–3 items appropriately answered | Adapted from project STOP Needlestick |

| 1. hepatitis B (right) 2. hepatitis C (false) 3. HIV (right) | ||||

| 4 (OS-comp) (score) | Competency for appropriate behaviour in the case of a needlestick injury (multiple choice) | You injured yourself with a used needle by sticking your fingertip. What should be done immediately? | 0–5 items appropriately answered | “ |

| 1. Put pressure on the affected area to stop the blood flow. (false) 2. Exercise pressure on hand and finger to increase the blood flow (“milk-out”) (right) 3. Rinse the affected area with hydrogen peroxide. (false) 4. Rinse the affected area with an antiseptic. (right) 5. Enlarge the injury with a scalpel. (false) | ||||

| 5 OS-info (item) | Subjective information status to handle a needlestick injury appropriately | Do you feel sufficiently informed to deal with a “needlestick injury emergency?” | resp. cat. 0 = no 1 = yes | “ |

| Percent Values | Percent | Cases (Valid) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses | Physicians | Total | Nurses | Physicians | Total | |||||||||||

| Sex (female) | 80.7 | 46.3 | 72.1 | 405 | 136 | 541 | ||||||||||

| Supervisor function (yes) | 13.0 | 38.1 | 19.3 | 400 | 134 | 534 | ||||||||||

| Unlimited employment/permanent contract (yes) | 94.3 | 29.3 | 78.1 | 402 | 133 | 535 | ||||||||||

| Employment contract > 75% (yes) | 60.9 | 93.5 | 69.3 | 396 | 138 | 535 | ||||||||||

| Mean values | Nurses | Physicians | Total | |||||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Min-Max | N | Mean | SD | Min-Max | N | Mean | SD | Min-Max | N | |||||

| Age | 39.9 | 11.2 | 20–63 | 384 | 37.6 | 8.7 | 24–65 | 129 | 39.3 | 10.6 | 20–65 | 513 | ||||

| Job tenure (years) | 16.2 | 11.3 | 0–42 | 354 | 9.4 | 8.0 | 0–39 | 117 | 14.5 | 11.0 | 0–42 | 471 | ||||

| Employment in hospital (years) | 14.3 | 9.7 | 0–41 | 343 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 0–38 | 112 | 12.6 | 9.5 | 0–41 | 455 | ||||

| Employment in current department (years) | 8.9 | 8.1 | 0–37 | 336 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 0–21 | 112 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 0–37 | 448 | ||||

| Workload (hours/week) | 33.9 | 8.5 | 8–41 | 244 | 41.0 | 6.3 | 19–70 | 107 | 36.0 | 7.8 | 8–70 | 351 | ||||

| No. | Patient Safety–Knowledge and Competencies (Sum Score Means) (n = 410) * | Mean | SD | Min-Max | All Correct (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PS-know | Knowledge about appropriate measures to avoid bladder catheter associated infections (multiple choice; possible range 0–6) | 4.14 | 1.00 | 1–6 | 13.9 |

| 2 PS-comp | Competency to detect and treat infections in patients with indwelling bladder catheters (multiple choice; possible range 0–3) | 2.22 | 0.54 | 0–3 | 24.3 |

| Occupational Safety–Knowledge and Competencies (Sum Score Means) (n = 547) | Mean | SD | Min-Max | All Correct (%) | |

| 3 OS-know | Knowledge about post-exposure prophylaxis of hepatitis B- and C-virus and HIV infection (multiple choice; possible range 0–3) | 1.97 | 0.62 | 0–3 | 13.7 |

| 4 OS-comp | Competency for appropriate behaviour in the case of a needlestick injury (multiple choice; possible range 0–5) | 4.57 | 0.69 | 1–5 | 66.9 |

| Occupational Safety–Subjective Information Status (Item Percent) (n = 547) | % | N | |||

| 5 OS-info | Subjective information status to treat a needlestick injury appropriately (feeling well informed; possible answers: yes/no) | 78.2 | 428 | - |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wagner, A.; Michaelis, M.; Luntz, E.; Wittich, A.; Schrappe, M.; Lessing, C.; Rieger, M.A. Assessment of Patient and Occupational Safety Culture in Hospitals: Development of a Questionnaire with Comparable Dimensions and Results of a Feasibility Study in a German University Hospital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122625

Wagner A, Michaelis M, Luntz E, Wittich A, Schrappe M, Lessing C, Rieger MA. Assessment of Patient and Occupational Safety Culture in Hospitals: Development of a Questionnaire with Comparable Dimensions and Results of a Feasibility Study in a German University Hospital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(12):2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122625

Chicago/Turabian StyleWagner, Anke, Martina Michaelis, Edwin Luntz, Andrea Wittich, Matthias Schrappe, Constanze Lessing, and Monika A. Rieger. 2018. "Assessment of Patient and Occupational Safety Culture in Hospitals: Development of a Questionnaire with Comparable Dimensions and Results of a Feasibility Study in a German University Hospital" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 12: 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122625

APA StyleWagner, A., Michaelis, M., Luntz, E., Wittich, A., Schrappe, M., Lessing, C., & Rieger, M. A. (2018). Assessment of Patient and Occupational Safety Culture in Hospitals: Development of a Questionnaire with Comparable Dimensions and Results of a Feasibility Study in a German University Hospital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(12), 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122625