Screaming Body and Silent Healthcare Providers: A Case Study with a Childhood Sexual Abuse Survivor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Aspects of the Study

2.2. Validity and Reliability

3. Results

3.1. Anne’s Story

“I clearly remember when I was younger, maybe not right when the abuse was happening, but just afterwards—I would lie somewhere and escape to that feeling… I would always exit on the left side, I just left there, it wasn’t a conscious decision. It felt like I was asleep, but I was not sleeping. It didn’t matter what was happening, I just disconnected completely”.

3.2. The Burden of CSA on Anne’s Body

3.3. Childhood Physical Health Consequences

“When I was about 12–13 years old, the winter that my mother became pregnant with my sister and my stepfather began making sexual advances to me, I lost nearly all my sight and hearing for a while. My eardrums were perforated and I had a constant ear infection, just from stress”.

3.4. Adolescent Physical Health Consequences

“When I was 16–17, I started getting ovarian cysts, it was chronic… if things got bad, emotionally or stress in my personal life I got ovarian cysts and adhesions. It started as soon as I started having sex at around 16”.

“I was 17 with the father of my first child and all of a sudden I just fell down the day after we had sex, I felt excruciating pain in my uterus. I was sent to hospital by ambulance. There was always pain on the right side of my uterus”.

3.5. Adult Physical Health Consequences

“I nearly lost everything here on my right side: my ovary and Fallopian tube, it (the infection) was spreading everywhere. I was very sick that whole year. There was always something wrong somewhere (in the body)–(even) infection in my kidneys. The whole system had broken down”.

“When I regained consciousness, he told me that my uterus was full of nodules (…) I tell him to take them, and when you have opened me up, remove the right ovary. He said ‘no’, I said ‘yes’! ‘I have been in pain in my right ovary since… my girl was born. You open me up and you take it out’, and fortunately he did it… I could feel that something was wrong there”.

“The doctor told me after the operation that it looked good enough, nothing wrong with it. He said that if I hadn’t been so insistent, he wouldn’t have removed it… but seven days later I’m called in to the hospital because they had found first stage cancer in it… The doctor told me, ‘thank you for insisting and pushing me to do it, because within two years you would have been gone, it wouldn’t have been detected during that time’.”.

“But it’s always such a huge pain to go in for these check-ups. Today I need to go and be checked for cancer… It is always just as painful. As time goes by, I’ve learned not to be there while it’s happening, I just ‘go out’, but this is just one of the many factors that may push women not to get checked, which increases the risk of cancer—it brings all kinds of bad feelings to the surface”.

3.6. Silent Healthcare Providers

“Once I told my gynecologist that I was always in such pain because of my womb, especially after sex, and I told him that it must have been because I was damaged back then when I was so small and sensitive down there, but I never got an answer”.

“When I was diagnosed with fibromyalgia, I… said that it was probably the result of stress in my teens. The doctor asked why I thought it was acquired, and I answered that I had been sexually abused as a child… and there was just silence, and we didn’t discuss it any further”.

3.7. The Wellness-Program—A Turning Point for Anne

“I had to learn to set boundaries. I needed to do exercises on my own in setting boundaries. I had to look at other people and notice for example how people acted in a crowd. I realized that personal space was something I did not know and had to create. Of course, I still make mistakes. I set boundaries regarding individuals who do not understand them, which I do not even understand myself. Sometimes I push people too far away from me or hurry to close myself, but I have been practicing”.

3.8. Anne’s Advice to Healthcare Providers

“The most wonderful thing was finding people who believed me. It’s all connected, it’s all about telling people your story and expressing yourself, being believed; what you say is heard. Somehow, it makes you feel complete. It’s not about pity (…), just being believed and like I said, to feel relieved. When someone recognizes that it’s not your fault. When you don’t tell your story, you are taking responsibility for what happened. ‘This was my entire fault so I won’t say a word’. When you tell your story, it’s no longer your fault; it’s someone else who should be ashamed”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Reflecting on Anne’s Story

4.2. Anne’s Suffering Body

4.3. Anne’s Sincere Help Seeking

4.4. Ideas for Further Research

4.5. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brower, V. Mind-body research moves towards the mainstream. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagundes, C.P.; Glaser, R.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Stressful early life experiences and immune dysregulation across the lifespan. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013, 27C, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leserman, J.; Drossman, D.A. Relationship of abuse history to functional gastrointestinal disorders and symptoms, some possible mediating mechanisms. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007, 8, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, P.A. In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 10-155-6-439-431. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, S.; Baldwin, N.; Taylor, J. Mental health problems and medically unexplained physical symptoms in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse: An integrative literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 19, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paras, M.L.; Hassan Murad, M.; Chen, L.P.; Goranson, E.N.; Sattler, A.L.; Colbenson, K.M.; Elamin, M.B.; Seime, R.J.; Prokop, L.J.; Zirakzadeh, A. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009, 302, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegman, H.L.; Stetler, C. A meta-analytic review of the effects of childhood abuse on medical outcomes in adulthood. Psychosom. Med. 2009, 71, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, D.P.; Wheaton, A.G.; Anda, R.F.; Croft, J.B.; Edwards, V.J.; Liu, Y.; Sturgis, S.L.; Perry, G.S. Adverse childhood experiences and sleep disturbances in adults. Sleep Med. 2011, 12, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S. Repressed and silent suffering: Consequences of childhood sexual abuse for women’s health and well-being. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 27, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Korff, M.; Alonso, J.; Ormel, J.; Angermeyer, M.; Bruffaerts, R.; Fleiz, C.; de Girolamo, G.; Kessler, R.C.; Kovess-Masfety, V.; Posada-Villa, J.; et al. Childhood psychosocial stressors and adult onset arthritis: Broad spectrum risk factors and allostatic load. Pain 2009, 143, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, S.R.; Fairweather, D.; Person, W.S.; Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Croft, J.B. Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults. Psychosom. Med. 2009, 71, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.R. Health consequences of childhood sexual abuse. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2010, 46, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romans, S.; Belaise, C.; Martin, J.; Morris, E.; Raffi, A. Childhood abuse and later medical disorders in women: An epidemiological study. Psychother. Psychosom. 2002, 71, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall-Tackett, K. Psychological trauma and physical health: A psychoneuroimmunology approach to aetiology of negative health effects and possible interventions. Psychol. Trauma 2009, 1, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, K.R.; Howell, K.H.; Graham-Berrmann, S.A. Physical health in preschool children exposed to intimate partner violence. J. Fam. Violence 2012, 27, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Brown, D.W.; Dube, S.R.; Bremner, J.D.; Felitti, V.J.; Giles, W.H. Adverse childhood experiences and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, N.L.; Chapman, B.; Conwell, Y.; McCollumn, K.; Franus, N.; Cotescu, S.; Duberstein, P.R. Childhood sexual abuse is associated with physical illness burden and functioning in psychiatric patients 50 years of age and older. Psychosom. Med. 2009, 71, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, J.J.; Elzevier, H.W.; Pelger, R.C.; Putter, H.; Woorham-van der Zalm, P.J. Multiple pelvic floor complaints are correlated with sexual abuse history. J. Sex. Med. 2009, 6, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seith, A.; Teichman, J. Differences in the clinical presentation of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome in patients with or without sexual abuse history. J. Urol. 2008, 180, 2029–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereda, N.; Guilera, G.; Forns, M.; Gómez-Benito, J. The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijma, B.; Schei, B.; Swahnberg, K.; Hilden, M.; Offerdal, K.; Pikarinen, U.; Sidenius, K.; Steingrimsdottir, T.; Stoum, H.; Halmesmäki, E. Emotional, physical and sexual abuse in patients visiting gynaecology clinics: A Nordic cross sectional study. Lancet 2003, 361, 2107–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gault-Sherman, M.; Silver, E.; Sigfúsdóttir, I.D. Gender and the associated impairment of childhood sexual abuse: A national study of Icelandic youth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgeirsdottir, B.B.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Gudjonsson, G.H.; Sigurdsson, J.F. Associations between sexual abuse and family conflict/violence, self-injurious behavior, and substance use: The mediating role of depressed mood an anger. Child Abuse Negl. 2011, 35, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoresen, S.; Myhre, M.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Aakvaag, H.F.; Hjemdal, O.K. Violence against children, later victimisation, and mental health: A cross-sectional study of the general Norwegian population. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2015, 13, 26259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloppen, K.; Haugland, S.; Svedin, C.G.; Mæhle, M.; Breivik, K. Prevalence of child sexual abuse in the Nordic countries: A literature review. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2016, 25, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohler-Kuo, M.; Landolt, M.A.; Maier, T.; Meidert, U.; Schönbucher, V.; Schnyder, U. Child sexual abuse revisited: A population-based cross-sectional study among Swiss adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelhor, D.; Hotaling, G.; Lewis, I.A.; Smith, C. Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics and risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. 1990, 14, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briere, J.; Elliott, D.M. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2003, 27, 1205–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelhor, D.; Shattuck, M.A.; Turner, H.A.; Hamby, S.L. The lifetime prevalence of child sexual abuse and sexual assault assessed in late adolescence. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonomi, A.E.; Anderson, M.L.; Rivara, F.P.; Cannon, E.A.; Fishman, P.A.; Carrell, D.; Reid, R.J.; Thompson, R.S. Healthcare utilization and costs associated with childhood abuse. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chartier, M.J.; Walker, J.R.; Naimark, B. Health risk behavior and mental health problems as mediators of the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergusson, D.M.; McLeod, G.F.H.; Horwood, L.J. Childhood sexual abuse and adult developmental outcomes: Findings from a 30-year longitudinal study in New Zealand. Child Abuse Negl. 2013, 37, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.M.; Parsekar, S.S.; Nair, S.N. An epidemiological overview of child sexual abuse. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2014, 3, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, S.; Matos, A.P.; Oliveira, S. The moderating effect of gender: Traumatic experience and depression in adolescence. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 165, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, Y.; Timonen, V.; Kenny, R.A. The impact of childhood sexual abuse on the mental and physical health, and healthcare utilization of older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudbrack, R.; Manfro, P.H.; Kuhn, I.M.; Carvalho, H.W.; Lara, D.R. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger and weaker: How childhood trauma relates to temperament traits. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 62, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, M.J.; Aggen, S.H.; Kendler, K.S.; York, T.P.; Amstadter, A.B. An epidemiologic study of childhood sexual abuse and adult sleep disturbances. Psychol. Trauma 2016, 8, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, L.C.; Scarpa, A. Interpersonal difficulties mediate the relationship between child sexual abuse and depression symptoms. Violence Vict. 2015, 30, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobański, J.A.; Klasa, K.; Cyranka, K.; Müldner-Nieckowski, L.; Dembińska, E.; Rutkowski, K.; Smiatek-Mazgaj, B.; Mielimąka, M. Influence of cumulated sexual trauma on sexual life and relationship of a patient. Psychiatr. Pol. 2014, 48, 739–758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cantón-Cortés, D.; Cantón, J. Coping with CSA among college students and post-traumatic stress disorder: The role of continuity of abuse and relationship with the perpetrator. Child Abuse Negl. 2010, 34, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.; Burnette, M.L.; Cerulli, C. Correlations between sexual abuse histories, perceived danger and PTSD among intimate partner violence victims. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, C.; Barnow, S.; Wingenfeld, K.; Rose, M.; Löwe, B.; Grabe, H.J. Complex post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with somatization disorder. ANZJP 2009, 43, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Hart, O.; van Ochten, J.M.; van Son, M.J.; Steele, K.; Lensvelt-Mulders, G. Relations among peri-traumatic dissociation and post-traumatic stress: A critical review. J. Trauma Dissoc. 2008, 9, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S.; Bender, S.S. Consequences of childhood sexual abuse for health and well-being: Gender similarities and differences. Scand. J. Public Health 2014, 42, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halldorsdottir, S. The Vancouver School of Doing Phenomenology. In Qualitative Research Methods in the Service of Health; Fridlund, B., Hildingh, C., Eds.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2000; pp. 47–78. ISBN 91-44-01248-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, M.; Cooney, A. Research approaches related to phenomenology: Negotiating a complex landscape. Nurse Res. 2012, 20, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781452242569. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, A.J.; Durepos, G.; Wiebe, E. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781412956703. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, G. A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse and structure. Qual. Inq. 2011, 17, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelberg, H. The Phenomenological Movement: A Historical Introduction; Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1984; ISBN 109-0-24-72535-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S.; Bender, S.S. Personal resurrection: Female childhood sexual abuse survivors’ experience of the Wellness-Program. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 30, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaudo, E. Pain and dualism: Which dualism? J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2017, 23, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothschild, B. The Body Remembers; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-393-70327-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nijenhuis, E.R.S.; van der Hart, O. Dissociation in trauma: A new definition and comparison with previous formulations. J. Trauma Dissoc. 2013, 12, 416–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzano-Mojica, J.; Martínez-Taboas, A.; Sayers-Montalvo, S.K.; Cabiya, J.J.; Alicea-Rodríguez, L.E. Dissociation in sexually abused Puerto Rican children: A replication utilizing social workers as informers. J. Trauma Dissoc. 2012, 13, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elklit, A.; Christiansen, D.M. Risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in female help-seeking victims of sexual assault. Violence Vict. 2013, 28, 552–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, T.W.W.; Heim, C.M. A short review on the psychoneuroimmunology of posttraumatic stress disorder: From risk factors to medical comorbidities. Brain Behav. Immun. 2011, 25, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Li, J.Z.; Leserman, J.; Hu, Y.; Drossman, D.A. Relationship of abuse history and other risk factors with obesity among female gastrointestinal patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2006, 49, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, C.; Pinto Pereira, S.M. Childhood maltreatment and BMI trajectories to mid-adult life: Follow-up to age 50y in a British Birth Cohort. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, A.E.; Sartor, C.E.; Jonson-Reid, M.; Munn-Chernoff, M.A.; Eschenbacher, M.A.; Diemer, E.W.; Nelson, E.C.; Waldron, M.; Bucholz, K.K.; Madden, P.A.F.; et al. Associations between body mass index, post-traumatic stress disorder, and child maltreatment in young women. Child Abuse Negl. 2015, 45, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, L.; Nydegger, L.A.; Camarillo, G.; Trinidad, D.R.; Schramm, E.; Ames, S.L. Neurological changes in brain structure and functions among individuals with a history of childhood sexual abuse: A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. R. 2015, 57, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, E.M.J.; Liezmann, C.; Klapp, B.F.; Kruse, J. The neuroimmune connection interferes with tissue regeneration and chronic inflammatory disease in the skin. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1262, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, J.E.; Noll, J.G.; Putnam, F.W.; Trickett, P.K. Sexual and physical re-victimization among victims of severe childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2009, 33, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Abreu, L.C.; Krahé, B. Vulnerability to sexual victimization in female and male college students in Brazil: Cross-sectional and prospective evidence. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2014, 45, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClure, F.H.; Chavez, D.V.; Agars, M.D.; Peacock, M.J.; Matosian, A. Resilience in sexually abused women: Risk and protective factors. J. Fam. Violence 2008, 23, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putman, S.E. The monsters in my head: Posttraumatic stress disorder and the child survivor of sexual abuse. J. Couns. Dev. 2009, 87, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, D.; Widom, C.S. Child abuse and neglect, social support, and psychopathology in adulthood: A prospective investigation. Child Abuse Negl. 2013, 37, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Physical Consequences | Studies |

|---|---|

| Widespread and chronic pain | Leserman and Drossman, 2007 [3]; Levine, 2010 [4]; Nelson et al., 2012 [5]; Paras et al., 2009 [6]; Wegman and Stetler, 2009 [7]. |

| Sleeping problems | Chapman et al., 2011 [8]; Sigurdardottir and Halldorsdottir 2013 [9]; Wegman and Stetler, 2009 [7]. |

| Adult onset arthritis | Sigurdardottir and Halldorsdottir, 2013 [9]; Von Korff et al., 2009 [10]. |

| Fibromyalgia | Dube et al., 2009 [11]; Sigurdardottir and Halldorsdottir, 2013 [9]; Wilson, 2010 [12]. |

| Long-term fatigue, diabetes | Romans et al., 2002 [13]; Sigurdardottir and Halldorsdottir 2013 [9]. |

| Circulatory problems | Kendall-Tackett, 2009 [14]; Romans et al., 2002 [13]; Sigurdardottir and Halldorsdottir, 2013 [9]; Wegman and Stetler, 2009 [7]. |

| Digestive problems | Dube et al., 2009 [11]; Kendall-Tackett, 2009 [14]; Kuhlman et al., 2012 [15]; Leserman and Drosman, 2007 [3]; Levine, 2010 [4]; Nelson et al., 2012 [5]; Paras et al., 2009 [6]; Wegman and Stetler, 2009 [7]; Wilson, 2010 [12]. |

| Respiratory problems | Anda et al., 2008 [16]; Dube et al., 2009 [11]; Talbot et al., 2009 [17]; Wegman and Stetler 2009 [7]; Wilson, 2010 [12]. |

| Musculoskeletal problems | Sigurdardottir and Halldorsdottir, 2013 [9]; Talbot et al., 2009 [17]; Wegman and Stetler, 2009 [7]. |

| Reproductive problems | Beck et al., 2009 [18]; Paras et al., 2009 [6]; Seith and Teichman, 2008 [19]; Sigurdardottir and Halldorsdottir, 2013 [9]. |

| Neurological problems | Beck et al., 2009 [18]; Kendall-Tackett, 2009 [14]; Paras et al., 2009 [6]; Seth and Teichman, 2008 [19]; Wegman and Stetler, 2009 [7]. |

| Countries | Women | Authors | CSA Age before | Research Design | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worldwide 22 countries | 19.7% | Pereda et al., 2009 [20] | 18 years | Meta-analysis | Community and student samples |

| Iceland | 10.4% | Wijma et al., 2003 [21] | 18 years | Cross sectional study | 3641 women at gynecology centers |

| Iceland | 17.6% | Gault Sherman et al., 2009 [22] | 17 years | Cross sectional national survey | 8618 Icelandic youth |

| Iceland | 35.7% | Asgeirsdottir, 2011 [23] | 18 years | Cross sectional survey | 9085 Icelandic college students |

| Norway | 10.2% | Thoresen et al., 2015 [24] | 18 years | Cross sectional survey | 2435 women 2092 men aged 18–75 |

| Nordic Countries | 11–36% | Kloppen et al., 2016 [25] | 18 years | Literature review | |

| Swiss | 40.2% | Mohler-Kuo et al., 2014 [26] | 16 years | Cross sectional study | 6787 ninth grade adolescents |

| USA | 27% | Finkelhor et al., 1990 [27] | 18 years | National survey | Adults |

| USA | 32.3% | Briere and Elliott, 2003 [28] | 18 years | Random sample | 1442 adults |

| USA | 26.6% | Finkelhor et al., 2014 [29] | 17 years | National telephone surveys | Adults |

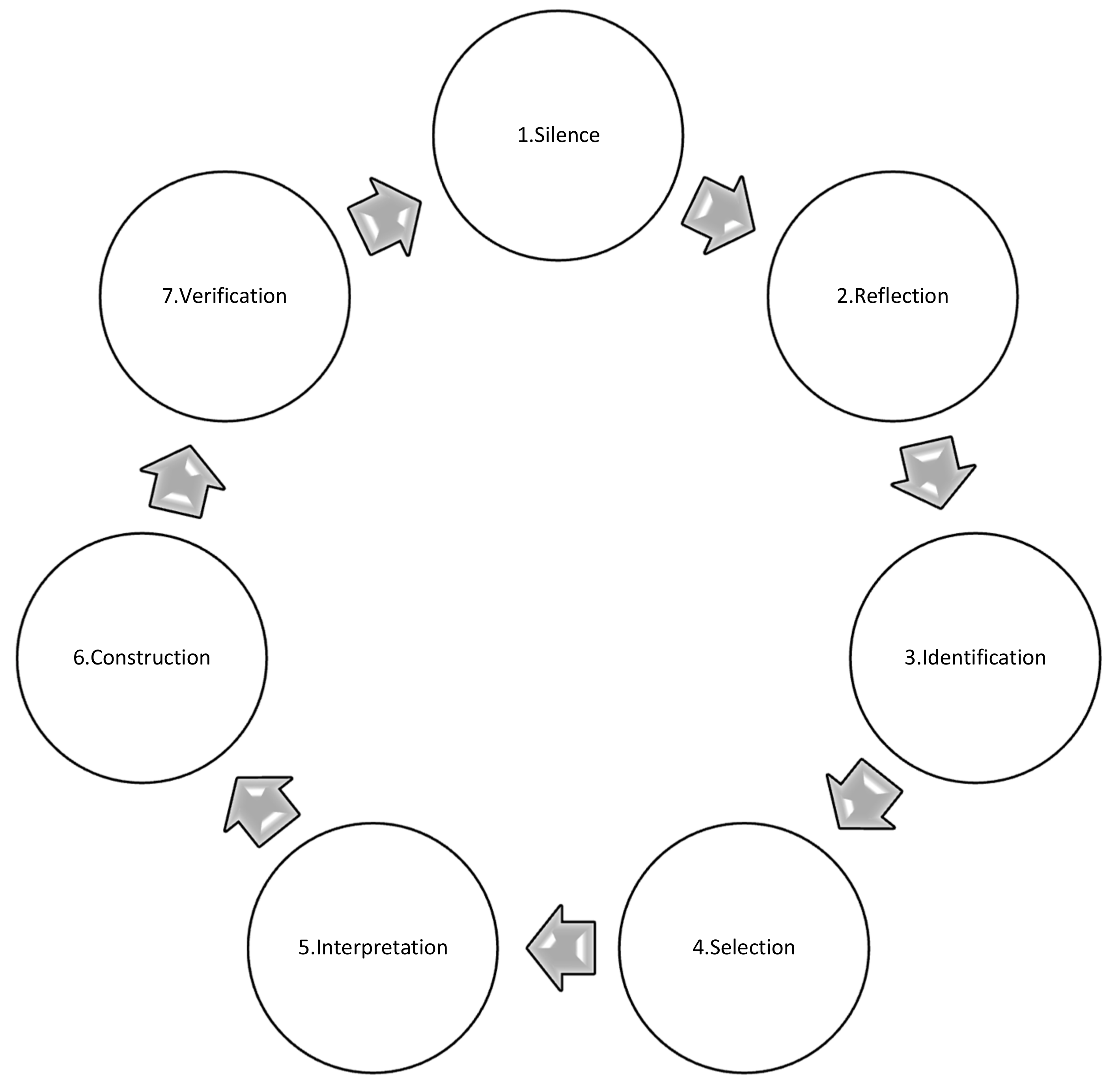

| Steps in the Research Process | Steps Taken in This Study |

|---|---|

| Step 1. Selecting dialogue partners (the sample). | One woman was selected through purposeful sampling. |

| Step 2. Silence (before entering a dialogue). | Preconceived ideas were deliberately put aside. |

| Step 3. Participating in a dialogue (data collection). | Seven interviews with the participant, the first author conducted all the interviews. |

| Step 4. Sharpened awareness of words (data analysis). | Data collecting and data analysis ran concurrently. |

| Step 5. Beginning consideration of essences (coding). | Trying repeatedly to answer the question: what is the essence of what the woman is saying? |

| Step 6. Deconstruction of the text and constructing the essential structure of the phenomenon from this case (individual case construction). | The main factors of each interview were highlighted, and the most important factors were used as building blocks for an individual case construction. |

| Step 7. Verifying each case construction with the relevant participant (verification). | This was carried out with the participant after each interview. |

| Step 8. Constructing the essential structure of the phenomenon from all the interviews (meta-synthesis of the interviews). | Two researchers participated in the data analysis process and made sure the case construction was based on the actual data. |

| Step 9. Comparing the essential structure of the phenomenon with the data (verification). | To ensure this, all the transcripts were read over again. |

| Step 10. Identifying the overriding theme that describes the phenomenon (construction of the main theme). | Screaming body and silent healthcare providers. |

| Step 11. Verifying the essential structure with the participant (verification). | The results and the conclusions were presented to and verified by the participant. |

| Step 12. Writing up the findings (reconstruction). | The participant is quoted directly to increase the trustworthiness of the findings and conclusions. |

| Anne’s Age | Psychological Traumas | Main Physical Problems |

|---|---|---|

| 2/3 until 9 | Anne’s father raped her when he had the chance | |

| 4 | Parent’s divorce | Physical symptoms started. Got very sick when she was sent to her father. Got mumps. Had chronic dizziness. |

| 6 | Often sick, as if she had the flu. | |

| 9–10 | Psychological abuse by her stepfather | Always tired, could always sleep, felt it was very difficult to breathe, to get the deep breath. |

| 10 | Raped by her uncle | |

| 12 | Raped by her stepfather | Lost her sight and hearing. Ear infections, eardrums perforated. Widespread pain and anxiety. |

| 13–14 | Raped by her friend’s father | Suspected appendicitis turned out to be gastritis. Depression, anxiety, colon spasm. |

| 14–15 | Went to boarding school. Bullying started at school | Pain, muscle aches, stomachaches, colon spasm. Started to numb her feelings with food, gained 10 kg during one summer, 20 kg in six months. |

| 16–17 | Colon spasm. Myositis in all her muscles. Appendectomy. Ovarian cysts and adhesions. Repeated urinary tract infections. Diagnosed with chlamydia. Always pain in right ovary. Acute pain after sex. Flashbacks and violent nightmares. | |

| 21 | Raped by a relative. Ex-stepfather tried to rape her | Heavy postpartum depression. Suicidal thoughts. Severe abdominal pain. |

| 24–27 | Ectopic pregnancies. Pilonidal cyst. Chronic urinary infection. Operated on twice to move adhesions. | |

| 30 | Operation to move adhesions. Cervical dysplasia. Went through cervical conization. Quit working because of chronic pain. | |

| 32–35 | Ectopic pregnancies. Insomnia. Fibromyalgia. Serious problems with the ovaries due to ruptured cysts. Arrhythmia. | |

| 36 | Hysterectomy (uterus removed) because of nodules. Heavy bleeding (menorrhagia), pain and endometrial hyperplasia. Operation due to an ovarian cyst and laparoscopic surgery because of another ovarian cyst on her right ovary. Diagnosed with cancer in ovaries. | |

| 39 | Para-thyroid adenoma. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S. Screaming Body and Silent Healthcare Providers: A Case Study with a Childhood Sexual Abuse Survivor. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010094

Sigurdardottir S, Halldorsdottir S. Screaming Body and Silent Healthcare Providers: A Case Study with a Childhood Sexual Abuse Survivor. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleSigurdardottir, Sigrun, and Sigridur Halldorsdottir. 2018. "Screaming Body and Silent Healthcare Providers: A Case Study with a Childhood Sexual Abuse Survivor" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010094

APA StyleSigurdardottir, S., & Halldorsdottir, S. (2018). Screaming Body and Silent Healthcare Providers: A Case Study with a Childhood Sexual Abuse Survivor. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010094