A Spatial Data Infrastructure for Environmental Noise Data in Europe †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Environmental Noise Data in Europe

1.2. Shared Environmental Information System

- Data heterogeneity. Infrastructures for the collection, maintenance and exchange of information in Europe are very different from each other. The political decision for the establishment of INSPIRE through a legislative approach provides the means for facing the challenge of setting-up and using a common infrastructure out of a transparent and inclusive approach which takes on board the views of all European member state stakeholders and institutions.

- Situations of lock-in. Despite the long lasting efforts for unlocking public data, considerable portions are still only available in data ‘silos’, which limit their use and reuse.

- Lack of trust. Both SEIS and INSPIRE aim to change the traditional model of data storage and maintenance and to provide the means for multiple use of same datasets. Making that possible would strongly depend apart from compliance with legally binding obligations also on mutual trust and willingness to share environmental data.

- Limited use of standards. Adoption of commonly agreed standards for encoding and transmission of information between institutions in Europe is still limited. At the same time the use of standards would provide a transparent approach for data governance and interoperability. That is why international standards are the ‘backbone’ of INSPIRE legal framework.

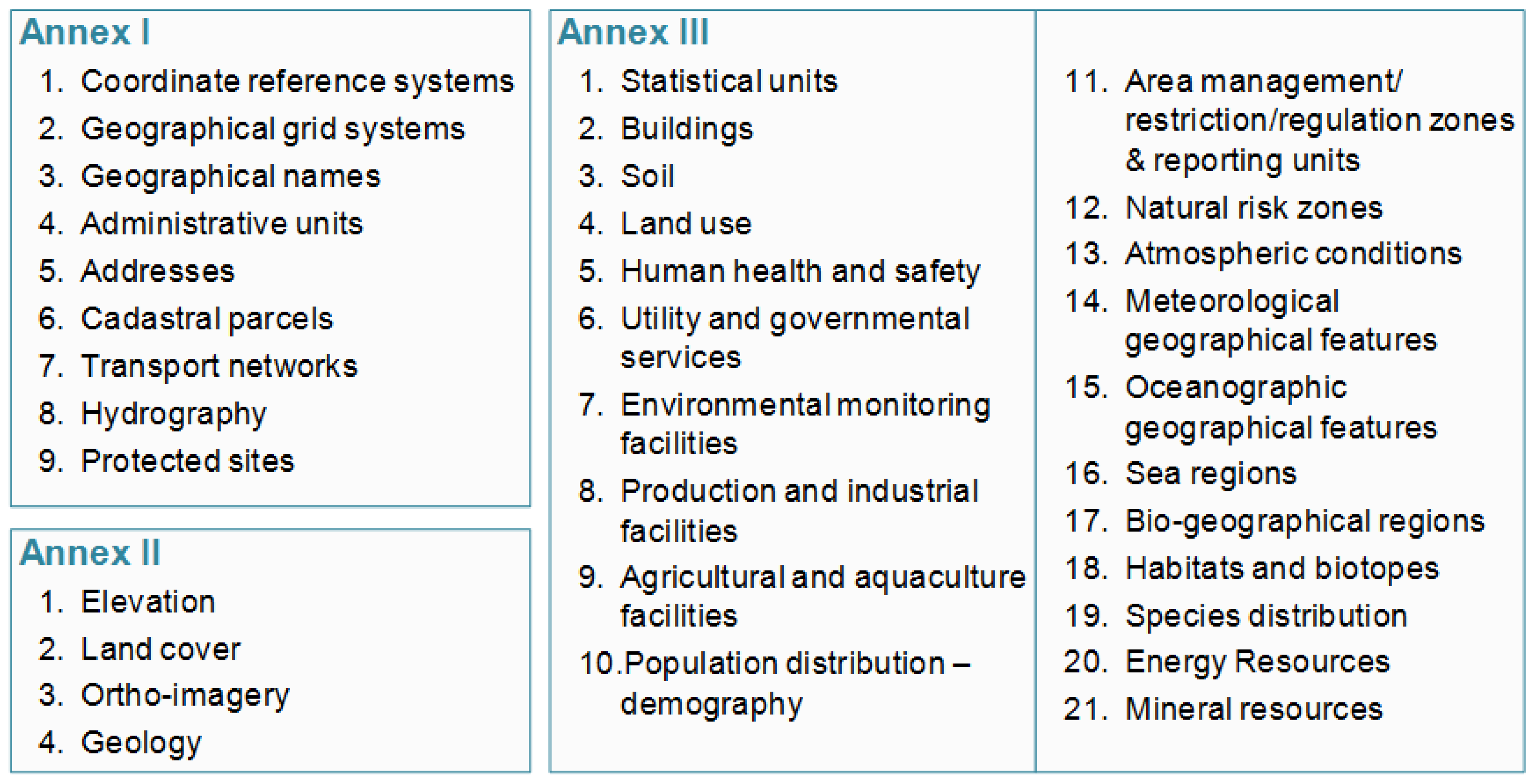

1.3. Infrastructure for Spatial Information in Europe

- Data should be collected only once and kept where it can be maintained most effectively.

- It should be possible to combine seamless spatial information from different sources across Europe and share it with many users and applications.

- It should be possible for information collected at one level/scale to be shared with all levels/scales; detailed for thorough investigations, general for strategic purposes.

- Spatial information needed for good governance at all levels should be readily and transparently available, fully available to the general public, to also enable citizen participation.

- Easy to find what Spatial information is available, how it can be used to meet a particular need, and under which conditions it can be acquired and used.

- Spatial data should become easy to understand and interpret because it can be visualized within the appropriate context selected in a user-friendly way

- Supported through common, free and open software standards.

2. A Spatial Data Infrastructures Perspective for Environmental Noise Data

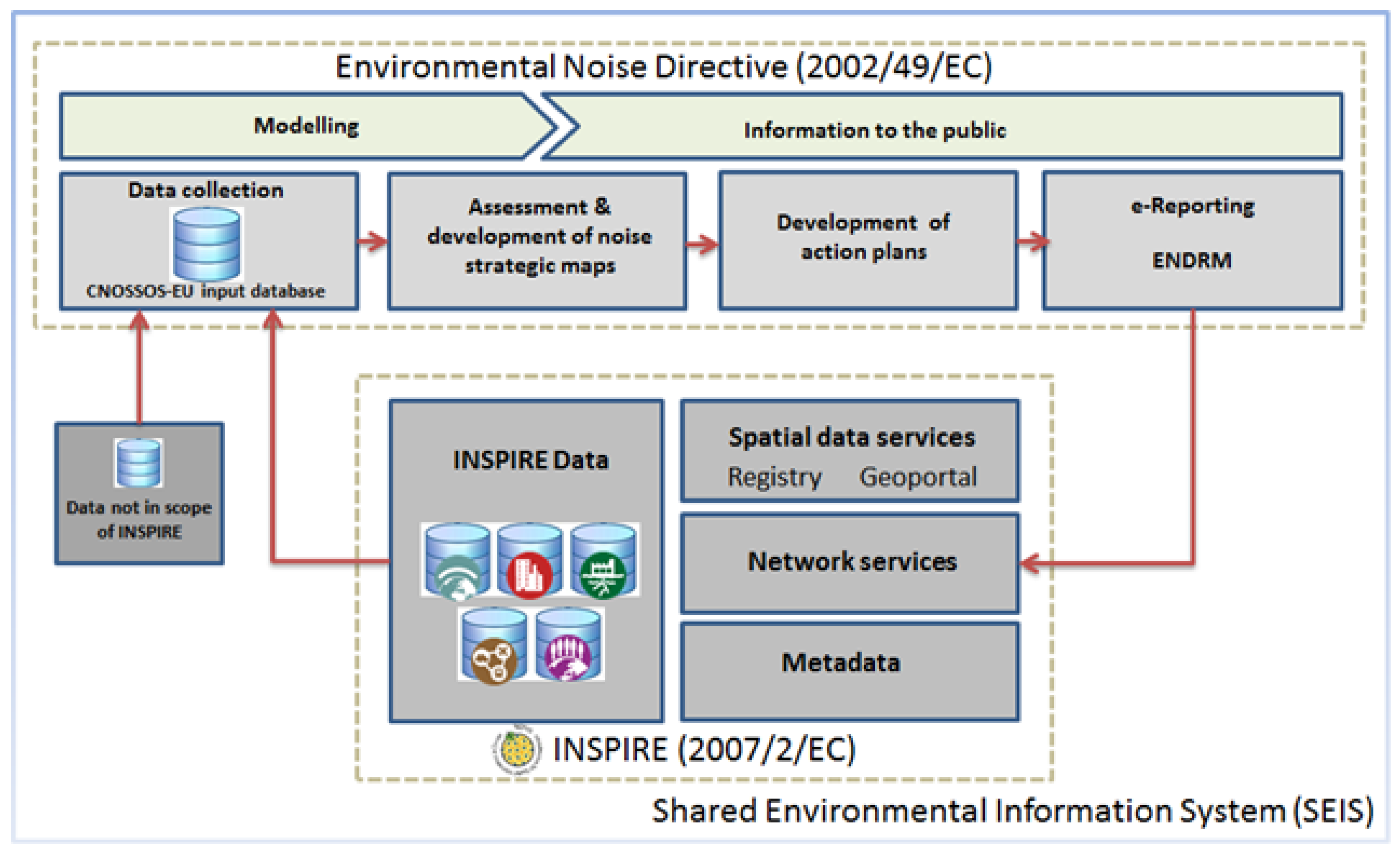

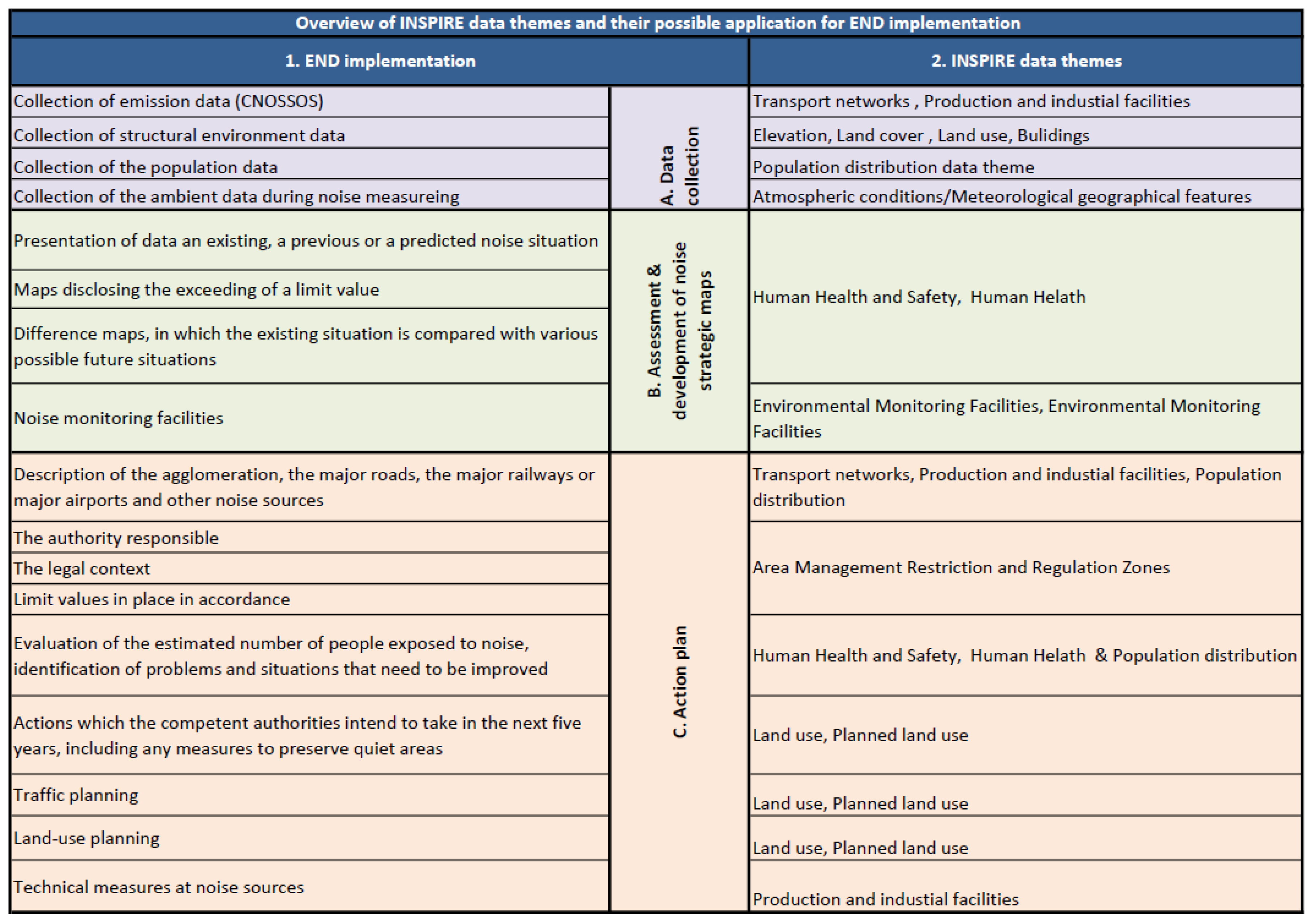

2.1. INSPIRE and Noise Modelling

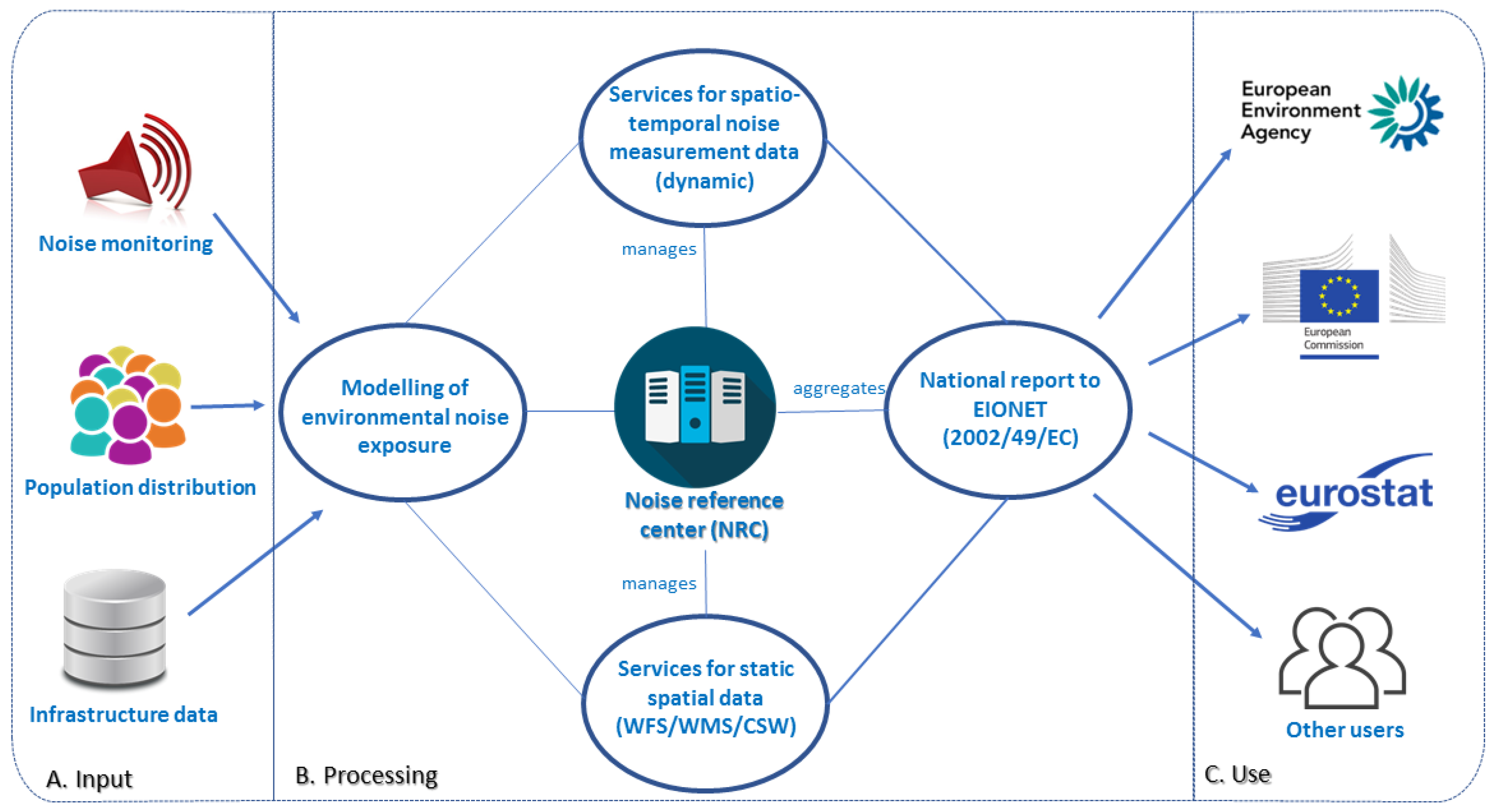

2.2. Support for Data Exchange and Reporting

2.3. Cross-Domain Interoperability

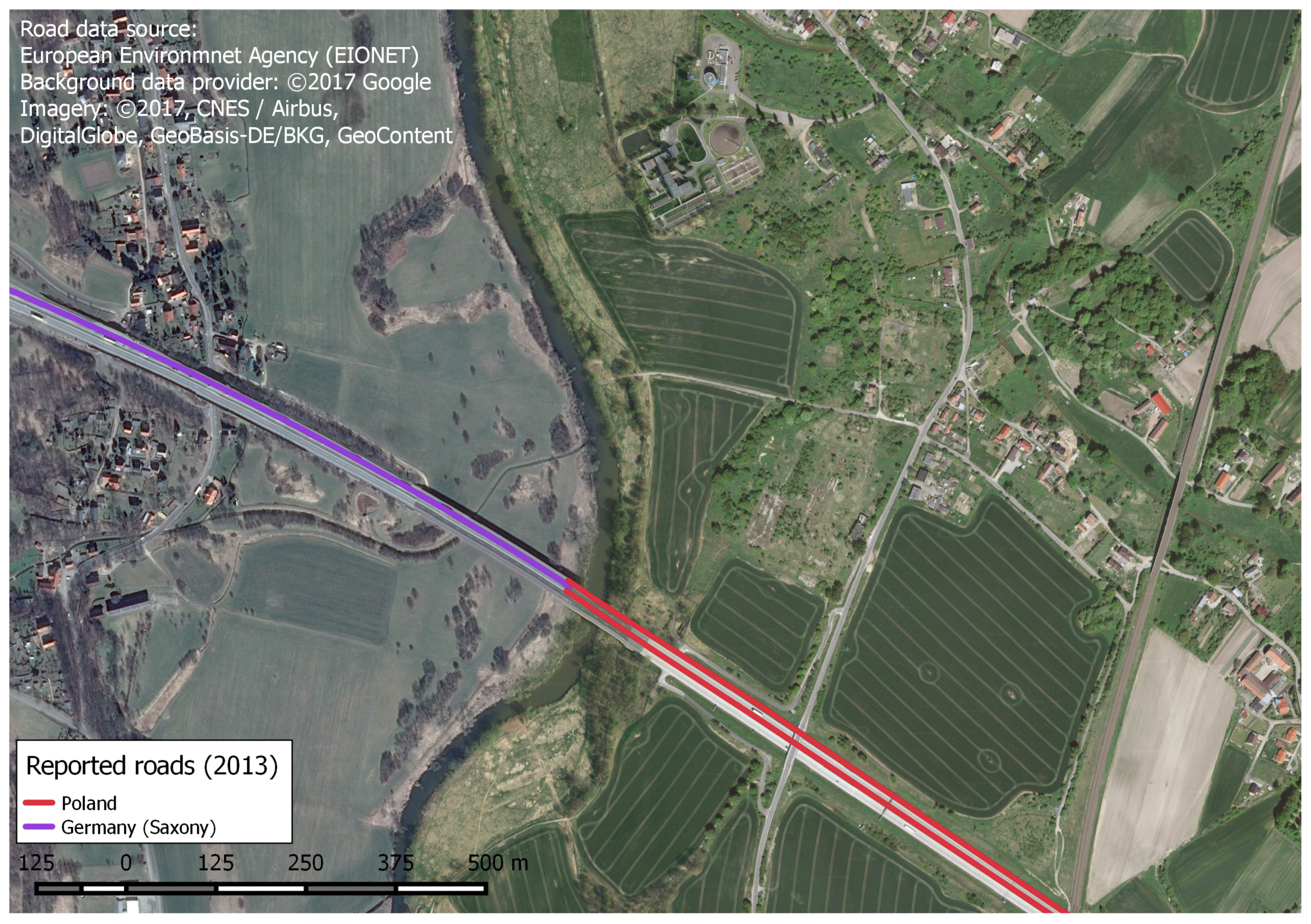

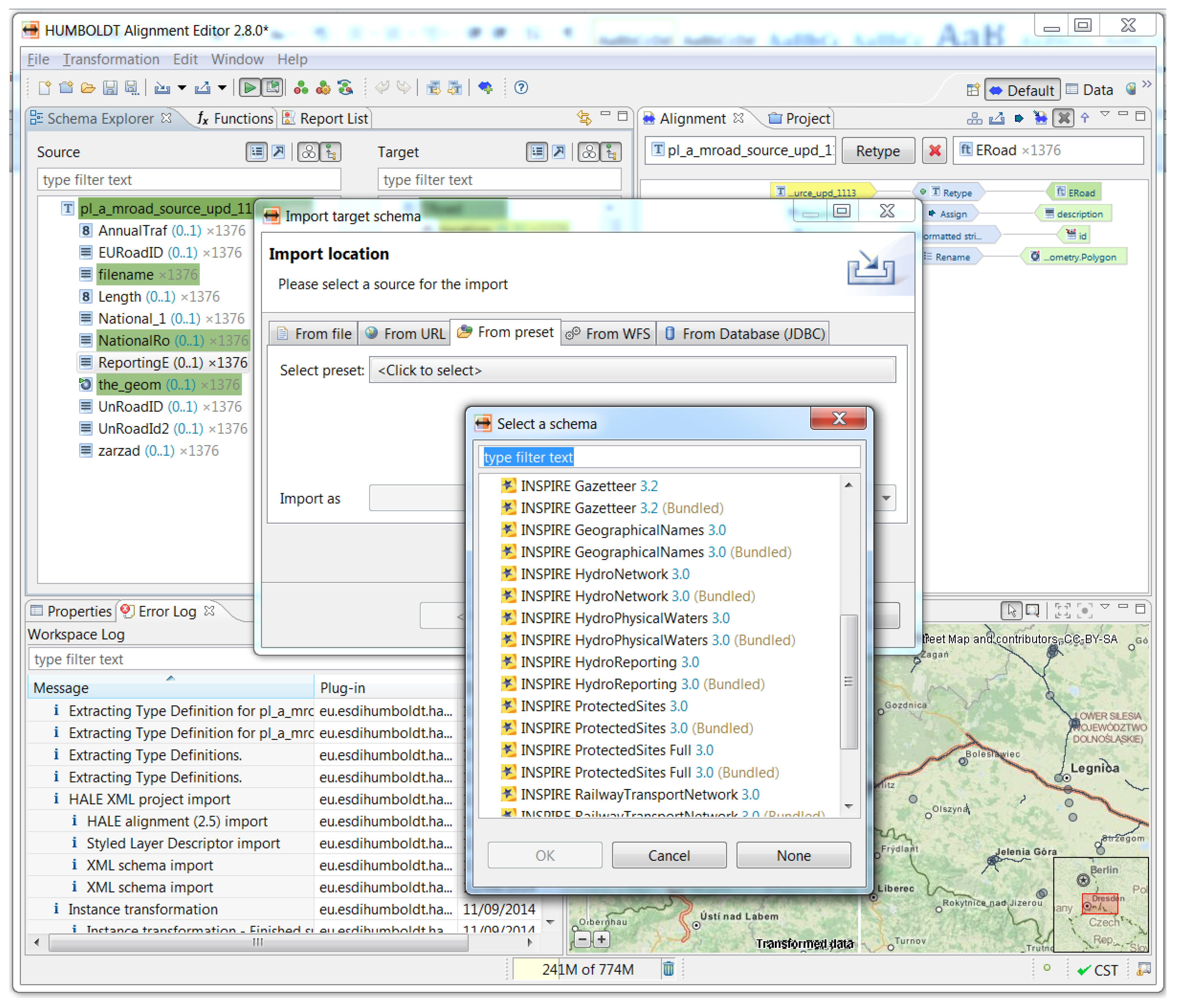

3. Data Harmonisation Use-Case

4. Conclusions

- Establishment of an INSPIRE/END e-reporting pilot project with the involvement of data providers and relevant pan-European actors

- Identification of possible extensions of existing INSPIRE data models in order to accommodate data needed for END purposes

- Use of interoperable network services in a Service Oriented Architecture (SOA) that would require a change of the currently existing data exchange paradigm from pushing data to the European level (EEA) to a ‘data pulling’ setting where data are harvested from a distributed set of national services

- Migration of the approach outside EU, possibly starting from neighbouring countries.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CONOSSOS-EU | Common Noise Assessment Methods in Europe |

| EEA | European Environment Agency |

| ETL | Extract-Transform-Load |

| ENDRM | END Reporting Mechanism |

| END | Environmental Noise Directive |

| EC | European Commission |

| HALE | Humboldt Alignment Editor |

| ISO | International Standardization Organization |

| INSPIRE | Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community |

| JRC | Joint Research Centre, European Commission |

| MS | Member States of the European Union |

| OGC | Open Geospatial Consortium |

| SEIS | Shared Environmental Information System |

| SDI | Spatial Data Infrastructure |

References

- Kephalopoulos, S.; Paviotti, M.; Ledee, F.A. Common Noise Assessment Methods in Europe (CNOSSOS-EU), 2012; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, A.W.; Peters, J.L.; Levy, J.I.; Melly, S.; Dominici, F. Residential exposure to aircraft noise and hospital admissions for cardiovascular diseases: multi-airport retrospective study. BMJ 2013, 347, f5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansell, A.L.; Blangiardo, M.; Fortunato, L.; Floud, S.; de Hoogh, K.; Fecht, D.; Ghosh, R.E.; Laszlo, H.E.; Pearson, C.; Beale, L.; et al. Aircraft noise and cardiovascular disease near Heathrow airport in London: Small area study. BMJ 2013, 347, f5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritschi, L.; Brown, L.; Kim, R.; Schwela, D.; Kephalopolous, S. Conclusions [Burden of Disease from Environmental Noise: Quantification of Healthy Years Life Lost in Europe]; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland; Joint Research Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hänninen, O.; Knol, A.B.; Jantunen, M.; Lim, T.A.; Conrad, A.; Rappolder, M.; Carrer, P.; Fanetti, A.C.; Kim, R.; Buekers, J.; et al. Environmental burden of disease in Europe: Assessing nine risk factors in six countries. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive, E.N. Directive 2002/49/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 June 2002 relating to the assessment and management of environmental noise. Off. J. L 2002, 189, 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, E.; King, E.A. Strategic environmental noise mapping: Methodological issues concerning the implementation of the EU Environmental Noise Directive and their policy implications. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kephalopoulos, S.; Paviotti, M.; Anfosso-Lédée, F.; Van Maercke, D.; Shilton, S.; Jones, N. Advances in the development of common noise assessment methods in Europe: The CNOSSOS-EU framework for strategic environmental noise mapping. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 482, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapelfeld, H.; Czerwinski, A. Sustainable environmental data infrastructure in support of acoustic modeling. In Proceedings of the 37th International Congress and Exhibition on Noise Control Engineering (INTER-NOISE 2008), Shanghai, China, 26–29 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J.; Usländer, T.; Schimak, G.; Esteban, J.F.; Denzer, R. An open distributed architecture for sensor networks for risk management. Sensors 2008, 8, 1755–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licitra, G.; Ascari, E. Gden: An indicator for European noise maps comparison and to support action plans. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 482, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive, I. Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE). Off. J. L 2007, 108, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Annoni, A.; Craglia, M.; Ehlers, M.; Georgiadou, Y.; Giacomelli, A.; Konecny, M.; Ostlaender, N.; Remetey-Fülöpp, G.; Rhind, D.; Smits, P.; et al. A European perspective on digital earth. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2011, 4, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.; Vallet, M. Study Related to the Preparation of a Communication on a Future EC Noise Policy: Final Report; Laboraroire Energie Nuisances (LEN): Bron, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Environment for Nordrhein-Westfalen. Available online: http://www.umgebungslaerm-kartierung.nrw.de/laerm/viewer.htm (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- IMAGINE Project. Specifications of GIS-NOISE Databases. Work Package 1, Deliverable 4. Document IMA10-TR25006-CSTB05. 2007. Available online: ftp://ftp.grenoble.cstb.fr/public/IMAGINE/IMA01-TR060526-CSTB05.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- The Report of the Commission COM (2011) 321 on the Implementation of the Environmental Noise Directive in Accordance with Article 11 of Directive 2002/49/EC. Brussels, Belgium, 2011. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32002L0049 (accessed on 10 May 2017).

- Schleidt, K. INSPIREd air quality reporting. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Environmental Software Systems, Neusiedl am See, Austria, 9–11 October 2013; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 439–450. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsev, A.; Peeters, O.; Smits, P.; Grothe, M. Building bridges: Experiences and lessons learned from the implementation of INSPIRE and e-reporting of air quality data in Europe. Earth Sci. Inform. 2015, 8, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consultation on the Evaluation of the Environmental Noise Directive. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/noise/pdf/consultation_results_evaluation_environmental_noise.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2017).

- Hřebíček, J.; Pillmann, W. Shared environmental information system and single information space in Europe for the environment: Antipodes or associates. In Proceedings of the European Conference of the Czech Presidency of the Council of the EU towards eEnvironment. Opportunities of SEIS and SISE: Integrating Environmental Knowledge in Europe, Prague, Czech Republic, 25–27 March 2009; Masaryk University: Brno, Czech Republic, 2009. Available online: http://www.e-envi2009.org/proceedings (accessed on 16 May 2017).

- Kotsev, A.; Kephalopoulos, S.; Abramic, A.; Smits, P.; Lima, V.; De Groof, H.; Pavotti, M. GIS Data and Noise Maps: Shall They be INSPIRE Compliant? In Proceedings of the 10th European Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering (EuroNoise 2015), Maastricht, The Netherlands, 31 May–3 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- IOCTF-NS, I. Technical Guidance for the Implementation of INSPIRE Download Services. 2013. Available online: http://inspire.ec.europa.eu/documents/Network_Services/Technical_Guidance_Download_Services_v3 (accessed on 16 May 2017).

- European Environment Agency. Electronic Noise Data Reporting Mechanism. A Handbook for Delivery of Data in Accordance with Directive 2002/49/EC; EEA Technical Report No. 9/2012; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Terrestrial Reference System. 1989. Available online: http://www.spatialreference.org/ref/epsg/4258/ (accessed on 16 June 2017).

- Stapelfeldt, H.; Siepmann, D.; Czerwinski, A.; Hoar, C. Solving large area noise mapping tasks. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Noise and Vibration Engineering (ISMA2010) and the 3rd International Conference on Uncertainty in Structural Dynamics (USD2010), Leuven, Belgium, 20–22 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Czerwinski, A.; Sandmann, S.; Stöcker-Meier, E.; Plümer, L. Sustainable SDI for EU noise mapping in NRW-best practice for INSPIRE. IJSDIR 2007, 2, 90–111. [Google Scholar]

- Guarinoni, M.; Ganzleben, C.; Murphy, E.; Jurkiewicz, K. Towards a Comprehensive Noise Strategy; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Central Data Repository—CDR. Available online: http://cdr.eionet.europa.eu/de/eu/noise (accessed on 10 April 2017).

- Reitz, T.; Templer, S. An environment for the conceptual harmonisation of geospatial schemas and data. Multidisciplinary research on geographical information in europe and beyond. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Geographic Information Science (AGILE’2012), Avignon, France, 24–27 April 2012; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abramic, A.; Kotsev, A.; Cetl, V.; Kephalopoulos, S.; Paviotti, M. A Spatial Data Infrastructure for Environmental Noise Data in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14070726

Abramic A, Kotsev A, Cetl V, Kephalopoulos S, Paviotti M. A Spatial Data Infrastructure for Environmental Noise Data in Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(7):726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14070726

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbramic, Andrej, Alexander Kotsev, Vlado Cetl, Stylianos Kephalopoulos, and Marco Paviotti. 2017. "A Spatial Data Infrastructure for Environmental Noise Data in Europe" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 7: 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14070726

APA StyleAbramic, A., Kotsev, A., Cetl, V., Kephalopoulos, S., & Paviotti, M. (2017). A Spatial Data Infrastructure for Environmental Noise Data in Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(7), 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14070726