Effects of Regular Classes in Outdoor Education Settings: A Systematic Review on Students’ Learning, Social and Health Dimensions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

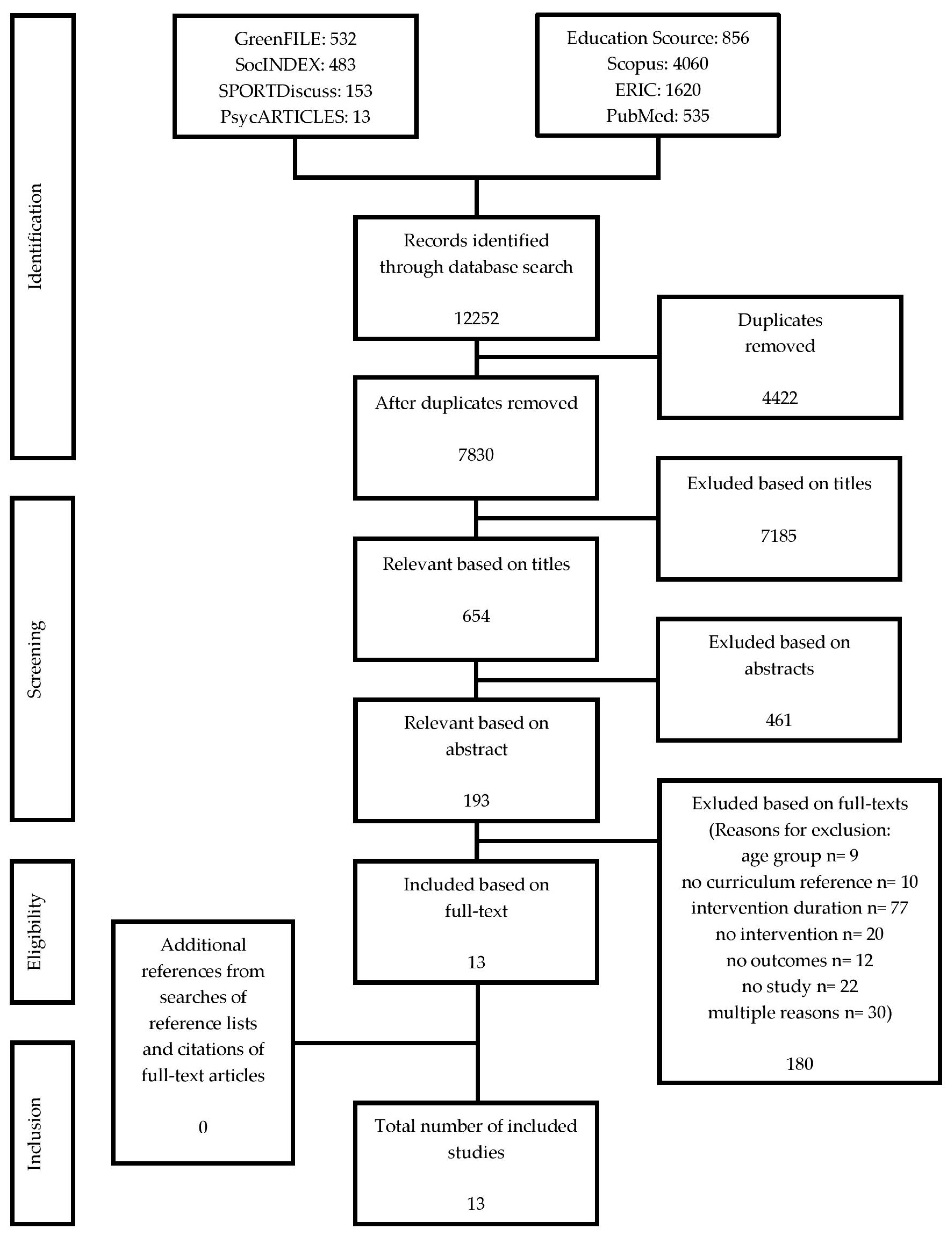

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- All types of study designs (e.g., control group design, quasi-experimental design, and case studies);

- Any type of formal school- and curriculum-based outdoor education programme involving children and adolescents (5–18 years);

- Regular weekly or bi-weekly classes in a natural or cultural environment outside the classroom with at least four hours of compulsory educational activities per week over a period of at least two months; and

- At least one reported outcome on a student level.

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

- Study characteristics: Citation, author, date of publication, journal, study-design, and country;

- Population: Age, gender, sample size, and type of school;

- Intervention characteristics: intervention and data acquisition period, and amount of intervention;

- Methodology and analytic process.

- Reported outcomes and main results.

- Barriers and limitations.

- Information for assessment of the risk of bias; and

- Source(s) of research/project funding and potential conflicts of interest.

2.5. Analysis and Synthesis

2.6. Methodological Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Methodological Quality Assessment of Included Studies

3.3. Categorised Outcomes

3.3.1. Outcomes on Learning Dimensions

3.3.2. Outcomes on Social Dimensions

3.3.3. Additional Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. General Aspects

4.2. Methodological Quality Assessment

4.3. Learning Dimensions

4.4. Social Dimensions

4.5. Additional Dimensions

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Source | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q8 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mygind [4] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mygind [27] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 0.08 | 0.79 |

| Martin et al. [29] | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.52 |

| Moeed et al. [32] | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −0.50 | 0.80 |

| Gustafsson et al. [5] | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.66 | 0.49 |

| Ernst et al. [31] | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 0.33 | 0.65 |

| Source | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dettweiler et al. [23] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.78 | 0.67 |

| Hartmeyer et al. [6] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 0.56 | 0.88 |

| Santelmann et al. [30] | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.86 |

| Moeed et al. [32] | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0.33 | 1 |

| Bowker et al. [35] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.78 | 0.67 |

| Sharpe [33] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 0.44 | 0.88 |

| Fiskum et al. [34] | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 0.33 | 0.87 |

| Wistoft [28] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0.56 | 0.88 |

| Ernst et al. [31] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0.56 | 0.88 |

References

- Waite, S.; Bølling, M.; Bentsen, P. Comparing apples and pears? A conceptual framework for understanding forms of outdoor learning through comparison of English forest schools and Danish udeskole. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickinson, M.; Dillon, J.; Teamey, K.; Morris, M.; Choi, M.; Sanders, D.; Benefield, P. A Review of Research on Outdoor Learning. Available online: https://www.field-studies-council.org/media/268859/2004_a_review_of_research_on_outdoor_learning.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2017).

- Hattie, J.A.; Marsh, H.W.; Neill, J.T.; Richards, G.E. Adventure education and outward bound: Out-of-class experiences that make a lasting difference. Rev. Educ. Res. 1997, 67, 43–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, E. A comparison between children’s physical activity levels at school and learning in an outdoor environment. J. Adv. Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2007, 2, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, P.E.; Szczepanski, A.; Nelson, N.; Gustafsson, P.A. Effects of an outdoor education intervention on the mental health of schoolchildren. J. Adv. Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2012, 12, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmeyer, R.; Mygind, E. A retrospective study of social relations in a Danish primary school class taught in “udeskole”. J. Adv. Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2015, 16, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, E. A comparison of children’s statements about social relations and teaching in the classroom and in the outdoor environment. J. Adv. Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2009, 9, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fägerstam, E.; Samuelsson, J. Learning arithmetic outdoors in junior high school—Influence on performance and self-regulating skills. Education 2014, 42, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, P. Six waves of outdoor education and still in a state of confusion: Dominant thinking and category mistakes. Kwartalnik Pedagogiczny 2016, 2, 176–184. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bentsen, P.; Mygind, E.; Randrup, T.B. Towards an understanding of udeskole: Education outside the classroom in a Danish context. Education 2009, 3, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Waite, S. Teaching and learning outside the classroom: Personal values, alternative pedagogies and standards. Education 2011, 39, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, P.; Jensen, F.S.; Mygind, E.; Randrup, T.B. The extent and dissemination of udeskole in Danish schools. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barfod, K.; Ejbye-Ernst, N.; Mygind, L.; Bentsen, P. Increased provision of udeskole in Danish schools: An updated national population survey. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Danish Ministry of Education. Improving the Public School; The Danish Ministry of Education: Copenhagen, Danmark, 2014.

- Bavarian Federal Ministry for Education, Cultural Affairs and Science. Available online: https://www.km.bayern.de/ (accessed on 3 March 2017).

- Finnish National Board of Education. Available online: http://www.oph.fi/english (accessed on 1 March 2017).

- Mikkola, A. Auf Weite Sicht. Reformen: Schon Wieder Finnland Im Porträt: Simone Fleischmann (Finnland -Armi Mikkola Über Radikale Reformen Aus Helsinki). Available online: https://www.bllv.de/fileadmin/Dateien/Land-PDF/BLLV-Medien/BS/Internt_Bayerische_Schule_04.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2017).

- Scrutton, R.; Beames, S. Measuring the unmeasurable: Upholding rigor in quantitative studies of personal and social development in outdoor adventure education. J. Exper. Educ. 2015, 38, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cason, D.; Gillis, H.L. A meta-analysis of outdoor adventure programming with adolescents. J. Exper. Educ. 1994, 17, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiennes, C.; Oliver, E.; Dickson, K.; Escobar, D.; Romans, A.; Oliver, S. The Existing Evidence-Base about the Effectiveness of Outdoor Learning. Available online: http://www.outdoor-learning.org/Portals/0/IOL%20Documents/Blagrave%20Report/outdoor-learning-giving-evidence-revised-final-report-nov-2015-etc-v21.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2017).

- Newman, M.; Elbourne, D. Improving the usability of educational research: Guidelines for the reporting of primary empirical research studies in education (the REPOSE guidelines). Eval. Res. Educ. 2004, 18, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Group, P.-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettweiler, U.; Ünlü, A.; Lauterbach, G.; Legl, A.; Simon, P.; Kugelmann, C. Alien at home: Adjustment strategies of students returning from a six-months over-sea’s educational programme. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2015, 44, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child Care and Early Education Research Connections. Available online: https://www.researchconnections.org/childcare/welcome (accessed on 1 March 2017).

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyes, J.; Hannes, K.; Booth, A.; Harris, J.; Harden, A.; Popay, J.; Pearson, A.; Pantoja, T. Qualitative Research and Cochrane Reviews; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wistoft, K. The desire to learn as a kind of love: Gardening, cooking, and passion in outdoor education. J. Adv. Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2013, 13, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Bright, A.; Cafaro, P.; Mittelstaedt, R.; Bruyere, B. Assessing the development of environmental virtue in 7th and 8th grade students in an expeditionary learning outward bound school. J. Exper. Educ. 2009, 31, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santelmann, M.; Gosnell, H.; Meyers, S.M. Connecting children to the land: Place-based education in the muddy creek watershed, Oregon. J. Geogr. 2011, 110, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.; Stanek, D. The prairie science class: A model for re-visioning environmental education within the national wildlife refuge system. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2006, 11, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeed, A.; Averill, R. Education for the environment: Learning to care for the environment: A longitudinal case study. Int. J. Learn. 2010, 17, 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, D. Independent thinkers and learners: A critical evaluation of the “growing together schools programme”. Pastoral. Care Educ. 2014, 32, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiskum, T.A.; Jacobsen, K. Outdoor education gives fewer demands for action regulation and an increased variability of affordances. J. Adv. Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2013, 13, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowker, R.; Tearle, P. Gardening as a learning environment: A study of children’s perceptions and understanding of school gardens as part of an international project. Learn. Environ. Res. 2007, 10, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.; Jungert, T.; Mageau, G.A.; Schattke, K.; Dedic, H.; Rosenfield, S.; Koestner, R. A self-determination theory approach to predicting school achievement over time: The unique role of intrinsic motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettweiler, U.; Lauterbach, G.; Becker, C.; Ünlü, A.; Gschrey, B. Investigating the motivational behaviour of pupils during outdoor science teaching within self-determination theory. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.K.J.; Ang, R.P.; Teo-Koh, S.M.; Kahlid, A. Motivational predictors of young adolescents’ participation in an outdoor adventure course: A self-determination theory approach. J. Adv. Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2004, 4, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproule, J.; Martindale, R.; Wang, J.; Allison, P.; Nash, C.; Gray, S. Investigating the experience of outdoor and adventurous project work in an educational setting using a self-determination framework. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2013, 19, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verloigne, M.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Maes, L.; Yıldırım, M.; Chinapaw, M.; Manios, Y.; Androutsos, O.; Kovács, É.; Bringolf-Isler, B.; Brug, J.; et al. Levels of physical activity and sedentary time among 10- to 12-year-old boys and girls across 5 European countries using accelerometers: An observational study within the energy-project. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merikangas, K.R.; Nakamura, E.F.; Kessler, R.C. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andrews, R. The place of systematic reviews in education research. Br. J. Educat. Stud. 2005, 53, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Nature of Learning: Using Research to Inspire Practice. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/50300814.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2017).

- Nielsen, G.; Mygind, E.; Bølling, M.; Otte, C.R.; Schneller, M.B.; Schipperijn, J.; Ejbye-Ernst, N.; Bentsen, P. A quasi-experimental cross-disciplinary evaluation of the impacts of education outside the classroom on pupils’ physical activity, well-being and learning: The teachout study protocol. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Source | N | Age | Distribution of Sex (% Male) | Country | Study Design | Administrator of Data Acquisition | Type of School |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mygind [4] | 19 | 9–10 | 26.3 | Denmark | case-study | chn | primary school |

| Mygind [7] | 19 | 9–10 | 26.3 | Denmark | case-study | chn | primary school |

| Dettweiler et al. [23] | 56 | 14–20 | n/a | Germany | cross-sectional retrospective | adol | secondary school |

| Hartmeyer et al. [6] | 5 adol, 2 t | 16 | 40 adol | Denmark | case-study retrospective | adol, t | primary school |

| Martin et al. [28] | 45 IG, 67 CG | 14–15 | 51.1 IG, 47.8 CG | USA | quasi-experimental | adol | secondary school |

| Santelmann et al. [29] | 40 | 12–15 | n/a | USA | case-study | chn, adol | secondary school |

| Moeed et al. [31] | 85 adol, 1 t | 15-24 | 61 adol | New Zealand | case-study | adol, adul, t | secondary school |

| Gustafsson et al. [5] | 121 IG, 109 CG | 8.6 ± 1.6 IG, 8.1 ± 1.5 CG | 56.2 IG, 51.4 CG | Sweden | quasi-experimental | chn | primary school |

| Bowker et al. [34] | 72 | 7–14 | n/a | UK, India, Kenya | case-study | chn, adol | primary + secondary school |

| Sharpe [32] | 9 chn, 2 t, 5 p, 2 s | 10–11 | n/a | UK | case-study | chn, t, p, s | primary school |

| Fiskum et al. [33] | 9 | 10–11 | 55.6 | Norway | case-study | chn | primary school |

| Wistoft [27] | 98 chn/t, 135 p, 6 s | - | n/a | Denmark | case-study | chn, p, t, s | primary school |

| Ernst et al. [30] | 90 chn, n/a p s | 10–11 chn | n/a | USA | quasi-experimental | chn, p, s | secondary school |

| Source | Data Collection | Intervention Period and Data Acquisition | Intervention Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mygind [4] | objectively-measured physical activity; accelerometry devise: CSA 7164 activity monitor | IP: school years 2000/2001/2002 DA: school years 2000/2001/2002 | three school years; one outdoor school day each week |

| Mygind [7] | adapted version of “About my self—a questionnaire for children” on self-perceived physical activity level, social relations and learning behaviour | IP: school years 2000/2001/2002/2003 DA: school years 2000/2001/2002/2003 | three school years; one outdoor school day each week |

| Dettweiler et al. [23] | postal survey; hand written letter | IP: 2008/2009/2010/2011 DA: 2012 | six months; each expedition |

| Hartmeyer et al. [6] | semi-structured interviews | IP: school years 2000/2001/2002/2003 DA: 2010 | three school years; one outdoor school day each week |

| Martin et al. [28] | Children’s Environmental Virtue Scale (CEVS) Questionnaire, adapted and modified by Children’s Environmental Attitude and Knowledge Scale (CHEAKS) | IP: 10/2005-01/2006 DA: 10/2005+01/2006 IG; spring semester 2006 CG | 10 weeks; at least one half day per week |

| Santelmann et al. [29] | interviews, written documents, learning assessment | IP: school year 2006/2007 DA: 2006/2007 | one school year; one outdoor school day in 1/3 of all weeks |

| Moeed et al. [31] | unspecified self-evaluation questionnaire, interviews, learning assessment | IP: 1997–1998 DA: 1997–1998 | two school years; four hours bi-weekly year nine; four hours weekly year 10 |

| Gustafsson et al. [5] | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), parent-version | IP: school year 2002/2003 DA: autumn 2002/autumn 2003 | one school year; five days per week; at least one hour per day |

| Bowker et al. [34] | concept maps, semi-structured group interviews, contextual observations, drawings | IP: school year 2004/2005 DA: school year 2004/2005 | one school year; four hours on average each week |

| Sharpe [32] | semi-structured individual interviews, group interview, observations | IP: school year 2012/2013 DA: summer/autumn 2013 | one school year; four hours on average each week |

| Fiskum et al. [33] | group interviews | IP: school years 2004–2008 DA: autumn 2008/spring 2009 | five school years; one outdoor day per week, years 1–4, one outdoor school day bi-weekly, year five |

| Wistoft [27] | group interviews, individual interviews, unspecified questionnaires | IP: school year 2010/2011 DA: school year 2010/2011 | eight weeks; one outdoor school day bi-weekly; 7–8 h on average per day |

| Ernst et al. [30] | Skills Self-Report questionnaire; Affective Self-Report and Parent Survey questionnaire, both developed by the author; standardised assessment test: Minnesota Comprehensive Assessments in Maths and Writing; individual interviews | IP: school year 2003/2004 DA: school year 2003/2004 | one school year; five days per week; two hours per day |

| Source | Outcomes on Learning Dimensions | Outcomes on Social Dimensions | Additional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mygind [4] | PA significant higher during outdoor classes compared to indoor classes (p < 0.001, 2000/2001); no significant differences in PA between outdoor classes and indoor classes including 2 PE lessons (p = 0.52, 2002); significant −level: 0.05 | ||

| Mygind [7] | higher preferences for learning in the outdoor setting compared to indoor setting; significant differences in three out of 14 statements | significant more positive social relations in the outdoor setting compared to the indoor setting (p < 0.001); significance-level: 0.05 | significant higher perceived PA in the outdoor setting (p < 0.01); significant −level: 0.05 |

| Dettweiler et al. [23] | long-term educational overseas expedition can lead to symptoms of a reverse culture shock; similar readjustment problems and development of coping strategies for all the participants, shown in a U-curve model; the longer the students had time to readjust, the more positive they report on perceived programme effects, shown as a linear function; no differences between cruises and gender | ||

| Hartmeyer et al. [6] | identification of six important conditions for the improvement of social relations: play, interaction, participation and pupil-centred tasks—important for positive social relations during udeskole; co-operation and engagement—consequences of improved social relations in subsequent years | ||

| Martin et al. [28] | IG: significant decrease in 5 CEVS domains: courage (p < 0.006); temperance (p = 0.084); acceptance (p = 0.014); compassion (p = 0.109); humility (p = 0.009); CG: significant decrease in courage (p = 0.169) and increase in temperance (p = 0.389); acceptance (p = 0.553); compassion (p = 0.796); humility (p = 0.553); significance-level: 0.1 | ||

| Santelmann et al. [29] | improved understanding of decision-making on farm and forest enterprises; insights into the global interconnectedness and ecodynamic drivers of agricultural markets | ||

| Moeed et al. [31] | year 10 students: improved horticulture skills (85% improved grade with 13%); year 9 students: strong level of commitment to develop knowledge and skills | former students: long term effects of the programme concerning positive environmental behaviour: growing own vegetables, participating in community-based planting programmes, taking own students outdoors within environmental projects, cleaning the Himalayas | |

| Gustafsson et al. [5] | overall positive, but not significant effect on mental health in the IG (p > 0.1); significant decrease in mental health problems for boys in IG compared to CG (p < 0.001); no significant differences for girls; significance-level: 0.1 | ||

| Bowker et al. [34] | gardening experience has a positive impact on curriculum learning: indication of direct association between gardening activities and improved learning | overall sense of pride, excitement and high self-esteem; gardening experience had a positive impact on students’ general school experience: indication of direct association between gardening activities and self-esteem | |

| Sharpe [31] | strong contextualised learning opportunities for children in Maths, English and Science; learning is perceived as fun through imaginative and creative learning opportunities; transfer from the indoor and outdoor classroom to real-life situations | building of trusting relationships and educationally-focused symbiotic relationships; growth in self-confidence; experience to take active responsibility for the environment | |

| Fiskum et al. [33] | gender differences: boys more often grasped affordances specific to the outdoor environment and used own creativity; girls more often grasped affordances not specific to the outdoor environment and used attached objects especially designed for them; girls more often regulate their action in the outdoor setting | ||

| Wistoft [27] | students developed a desire to learn through participation in the programme; they learned through enjoyment and experiences, they perceived learning as fun | students developed social competencies through participation in the programme | |

| Ernst et al. [30] | significant higher reading + writing scores for IG compared to CG (p = 0.03); positive significant increase in science process, problem-solving, technology skills, skills in working and communication for IG compared to CG (p < 0.01); students in the IG became more interested in school and learning fostered by outdoor learning | positive significant difference in students' attitudes towards the prairie wetlands environment for IG compared to CG (p = 0.02); IG students improved their classroom behaviour and prompted a sense of belonging |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Becker, C.; Lauterbach, G.; Spengler, S.; Dettweiler, U.; Mess, F. Effects of Regular Classes in Outdoor Education Settings: A Systematic Review on Students’ Learning, Social and Health Dimensions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14050485

Becker C, Lauterbach G, Spengler S, Dettweiler U, Mess F. Effects of Regular Classes in Outdoor Education Settings: A Systematic Review on Students’ Learning, Social and Health Dimensions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(5):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14050485

Chicago/Turabian StyleBecker, Christoph, Gabriele Lauterbach, Sarah Spengler, Ulrich Dettweiler, and Filip Mess. 2017. "Effects of Regular Classes in Outdoor Education Settings: A Systematic Review on Students’ Learning, Social and Health Dimensions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 5: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14050485

APA StyleBecker, C., Lauterbach, G., Spengler, S., Dettweiler, U., & Mess, F. (2017). Effects of Regular Classes in Outdoor Education Settings: A Systematic Review on Students’ Learning, Social and Health Dimensions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(5), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14050485