The Basic Act for Suicide Prevention: Effects on Longitudinal Trend in Deliberate Self-Harm with Reference to National Suicide Data for 1996–2014

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.4. Measurements

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

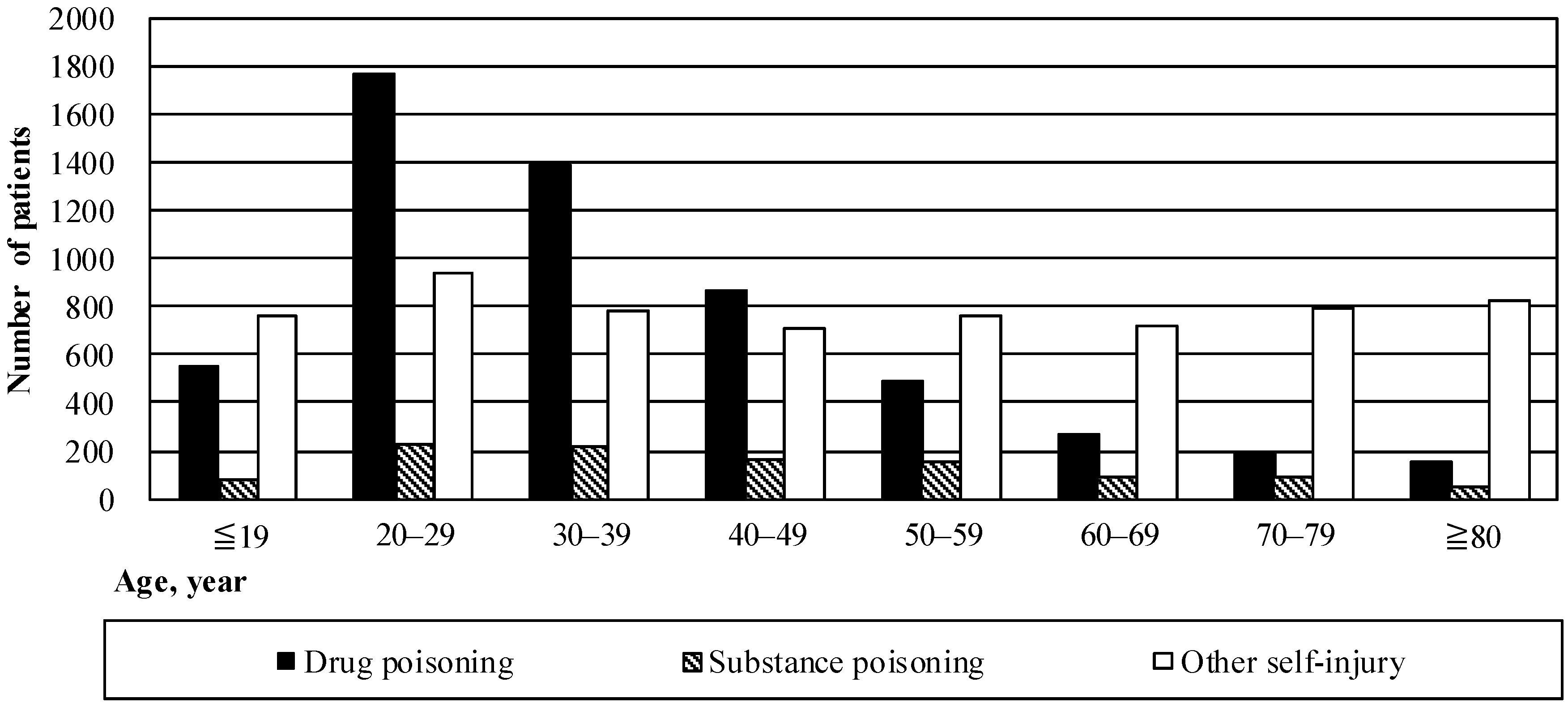

3.1. Patient Characteristics

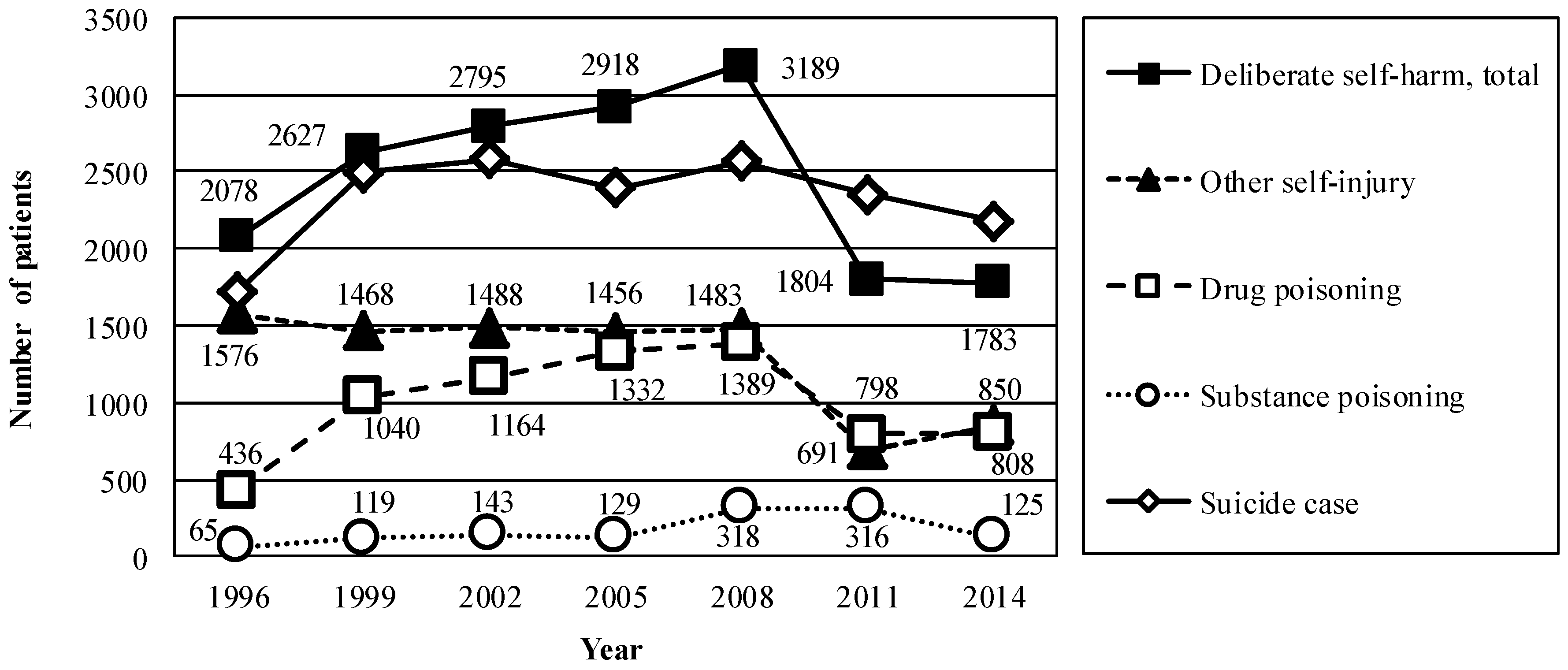

3.2. Estimation of the Number of Patients Who Engaged in Deliberate Self-Harm

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zahl, D.L.; Hawton, K. Repetition of deliberate self-harm and subsequent suicide risk: Long-term follow-up study of 11,583 patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004, 185, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.; Kapur, N.; Webb, R.; Lawlor, M.; Guthrie, E.; Mackway-Jones, K.; Appleby, L. Suicide after deliberate self-harm: A 4-year cohort study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, K.; Tanii, H.; Fukunaga, T.; Abe, S.; Nishimura, F.; Kimura, Y.; Nishimura, Y.; Nishida, A.; Kajiki, N.; Tawara, J.; et al. The importance of the frequency of suicide attempts as a risk factor of suicide. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2008, 15, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runeson, B.; Haglund, A.; Lichtenstein, P.; Tidemalm, D. Suicide risk after nonfatal self-harm: A national cohort study, 2000–2008. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skegg, K. Self-harm. Lancet 2005, 366, 1471–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Rodham, K.; Evans, E.; Weatherall, R. Deliberate self-harm in adolescents: Self report survey in schools in England. BMJ 2002, 325, 1207–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, M.; Kawashima, Y.; Kawanishi, C.; Yonemoto, N.; Sugimoto, T.; Furuno, T.; Ikeshita, K.; Eto, N.; Tachikawa, H.; Shiraishi, Y.; et al. Interventions to prevent repeat suicidal behavior in patients admitted to an emergency department for a suicide attempt: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfson, M.; Grameroff, M.J.; Marcus, S.C.; Greenberg, T.; Shaffer, D. Emergency treatment of young people following deliberate self-harm. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, C.; Hansford, L.; Sharkey, S.; Ford, T. Needs and fears of young people presenting at Accident and Emergency department following an act of self-harm: Secondary analysis of qualitative data. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- OECD Health Statistics 2016—Frequently Requested Data. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/OECD-Health-Statistics-2016-Frequently-Requested-Data.xls (accessed on 8 July 2016).

- 2015 White Paper on Suicide Prevention in Japan—Digest Version. Available online: http://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/9929094/www8.cao.go.jp/jisatsutaisaku//whitepaper/en/w-2015/summary.html (accessed on 20 January 2017).

- Nakanishi, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Takeshima, T. National strategy for suicide prevention in Japan: Impact of a national fund on progress of developing systems for suicide prevention and implementing initiatives among local authorities. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 69, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, P.; Griffin, E.; Arensman, E.; Fitzgerald, A.P.; Perry, I.J. Impact of the economic recession and subsequent austerity on suicide and self-harm in Ireland: An interrupted time series analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Outline of Survey. Available online: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hss/dl/sps_2014_00.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2016).

- Miller, T.R.; Furr-Holden, C.D.; Lawrence, B.A.; Weiss, H.B. Suicide deaths and non-fatal hospital admissions for deliberate self-harm: Temporality by day of week and month of year, United States. Crisis 2012, 33, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spittal, M.J.; Pirkis, J.; Miller, M.; Studdert, D.M. Declines in the lethality of suicide attempts explain the decline in suicide deaths in Australia. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tidemalm, D.; Beckman, K.; Dahlin, M.; Vaez, M.; Lichtenstein, P.; Långström, N.; Runeson, B. Age-specific suicide mortality following non-fatal self-harm: National cohort study in Sweden. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 1699–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handbook of Health and Welfare Statistics 2014, Part 3, Chapter 1, Table 3–5 Actual Number and Ratio of Public Assistance Recipients by Type of Assistance, by Fiscal Year. Available online: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hh/xls/3-05.xls (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- Iemmi, V.; Bantjes, J.; Coast, E.; Channer, K.; Leone, T.; McDaid, D.; Palfreyman, A.; Stephens, B.; Lund, C. Suicide and poverty in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, Y.; Fujita, J.; Matsumoto, T.; Tachimori, H.; Shimizu, S. Geographical variation in sedative-hypnotic use among recipients of public assistance: A nationwide survey. Jpn. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 17, 1561–1575. [Google Scholar]

- Okumura, Y.; Tachimori, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Nishi, D. Exposure to psychotropic medications prior to overdose: A case-control study. Psychopharmacology 2015, 232, 3101–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M.K.; Joiner, T.E.; Gordon, K.H.; Lloyd-Richardson, E.; Prinstein, M.J. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2006, 144, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, C.M.; Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Miller, A.L.; Turner, J.B. Psychiatric impairment among adolescents engaging in different types of deliberate self-harm. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2008, 37, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalesan, B.; Mobily, M.E.; Keiser, O.; Fagan, J.A.; Galea, S. Firearm legislation and firearm mortality in the USA: A cross-sectional, state-level study. Lancet 2016, 387, 1847–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vital Statistics of Japan. Volume 1, Table 5–36 Trends in Deaths and Percent Distribution from Suicide by Sex and External Causes: Japan. Available online: http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/GL76050103.do?_csvDownload_&fileId=000007635665&releaseCount=2 (accessed on 20 January 2017).

| Variable | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Follow up after discharge | |

| Decedents, n (%) | 471 (3.6) |

| Outpatient care from the hospital, n (%) | 5392 (41.4) |

| Outpatient care from another hospital, n (%) | 3730 (28.7) |

| Home healthcare, n (%) | 35 (0.3) |

| Other situation at home, unspecified, n (%) | 1941 (14.9) |

| Admission to another hospital, n (%) | 1030 (7.9) |

| Admission to geriatric intermediate care, n (%) | 67 (0.5) |

| Admission to residential facility, n (%) | 58 (0.4) |

| Other setting, unspecified, n (%) | 290 (2.2) |

| Year of discharge | |

| 1996, n (%) | 1271 (9.8) |

| 1999, n (%) | 1918 (14.7) |

| 2002, n (%) | 2043 (15.7) |

| 2005, n (%) | 2170 (16.7) |

| 2008, n (%) | 2508 (19.3) |

| 2011, n (%) | 1562 (12.0) |

| 2014, n (%) | 1542 (11.8) |

| Age, year, mean (standard deviation) † | 43.4 (21.5) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 5495 (42.2) |

| Duration of hospitalization, days, mean (standard deviation) ‡ | 15.7 (69.7) |

| Location of patient’s residence and hospital § | |

| Same municipality, n (%) | 6994 (54.2) |

| Different municipality in same region, n (%) | 3344 (25.9) |

| Different region in same prefecture (state), n (%) | 1904 (14.8) |

| Different prefecture, n (%) | 661 (5.1) |

| Receipt of public assistance, n (%) | 1112 (8.5) |

| Regional number of psychiatric beds per population, patient residence § | |

| <25th percentile, n (%) | 3864 (29.9) |

| 25–75th percentile, n (%) | 6588 (51.1) |

| >75th percentile, n (%) | 2450 (19.0) |

© 2017 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakanishi, M.; Endo, K.; Ando, S. The Basic Act for Suicide Prevention: Effects on Longitudinal Trend in Deliberate Self-Harm with Reference to National Suicide Data for 1996–2014. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010104

Nakanishi M, Endo K, Ando S. The Basic Act for Suicide Prevention: Effects on Longitudinal Trend in Deliberate Self-Harm with Reference to National Suicide Data for 1996–2014. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010104

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakanishi, Miharu, Kaori Endo, and Shuntaro Ando. 2017. "The Basic Act for Suicide Prevention: Effects on Longitudinal Trend in Deliberate Self-Harm with Reference to National Suicide Data for 1996–2014" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010104

APA StyleNakanishi, M., Endo, K., & Ando, S. (2017). The Basic Act for Suicide Prevention: Effects on Longitudinal Trend in Deliberate Self-Harm with Reference to National Suicide Data for 1996–2014. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010104