Housing Stakeholder Preferences for the “Soft” Features of Sustainable and Healthy Housing Design in the UK

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“Principle 1: Human beings are at the centre of concerns for sustainable development. They are entitled to a healthy and productive life in harmony with nature” [14].

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection

2.1.1. Sample

2.1.2. Measures

2.2. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

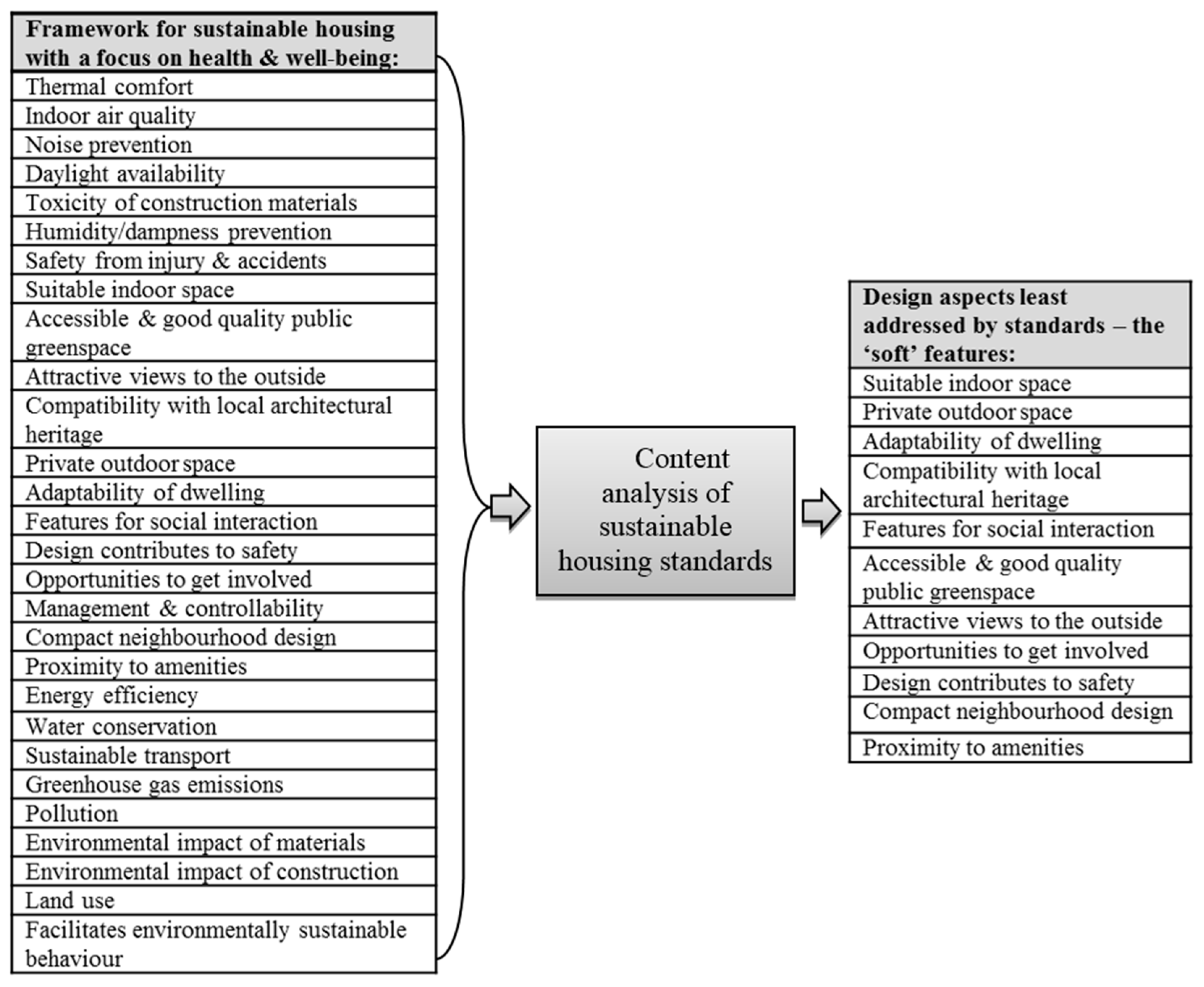

3.1. “Soft” Features of Sustainable Housing and Neighbourhood Design

3.2. Reliability

| Stakeholder Group | Average Measures ICC | |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Absolute Agreement | |

| “Housing users”: | 0.984 | 0.981 |

| Housing associations: | 0.974 | 0.969 |

| Local authorities: | 0.947 | 0.939 |

| Developers: | 0.968 | 0.953 |

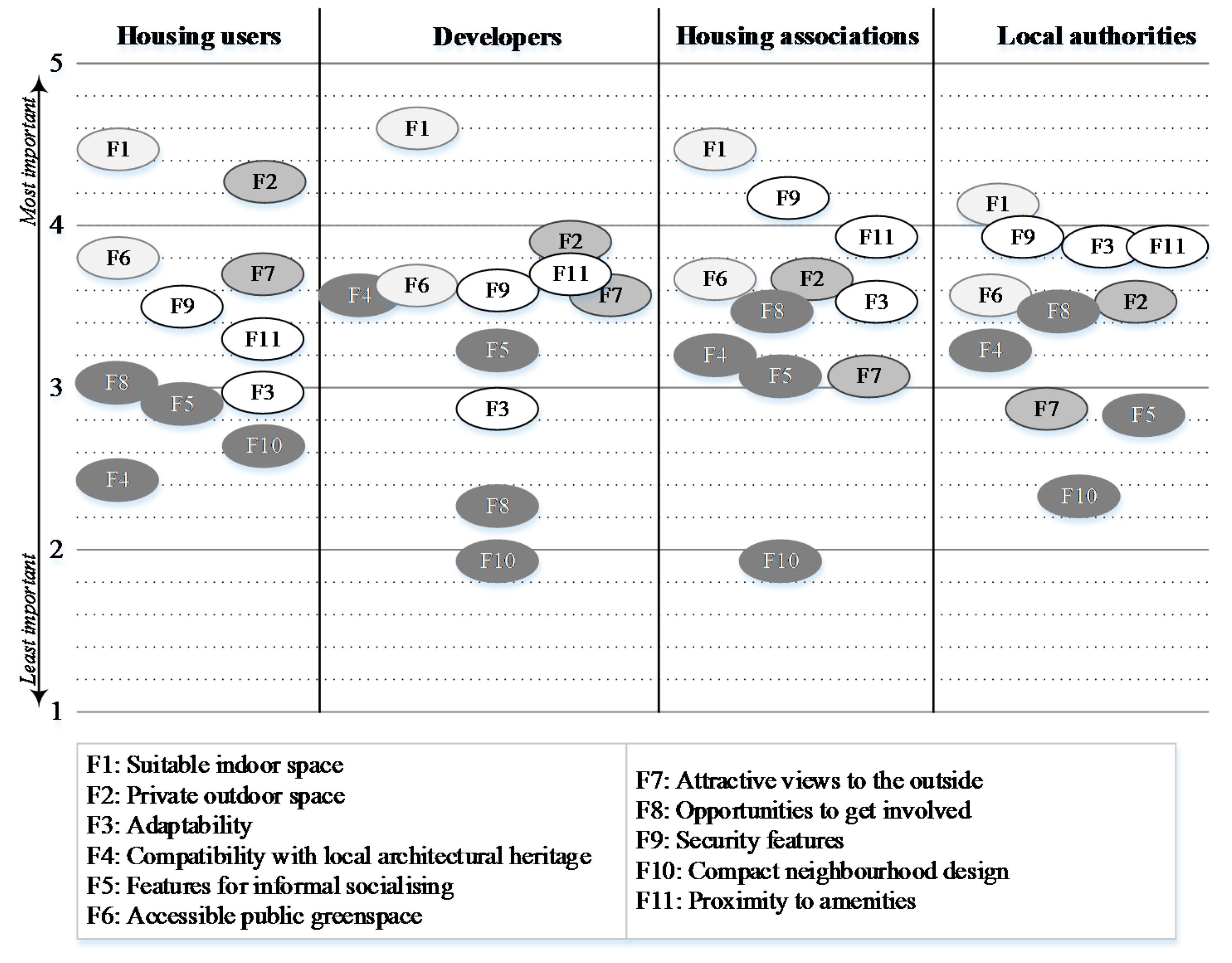

3.3. Importance Rating Scores

3.4. Comparing Opinions among Stakeholder Groups

3.4.1. “Housing Users” versus Housing Providers

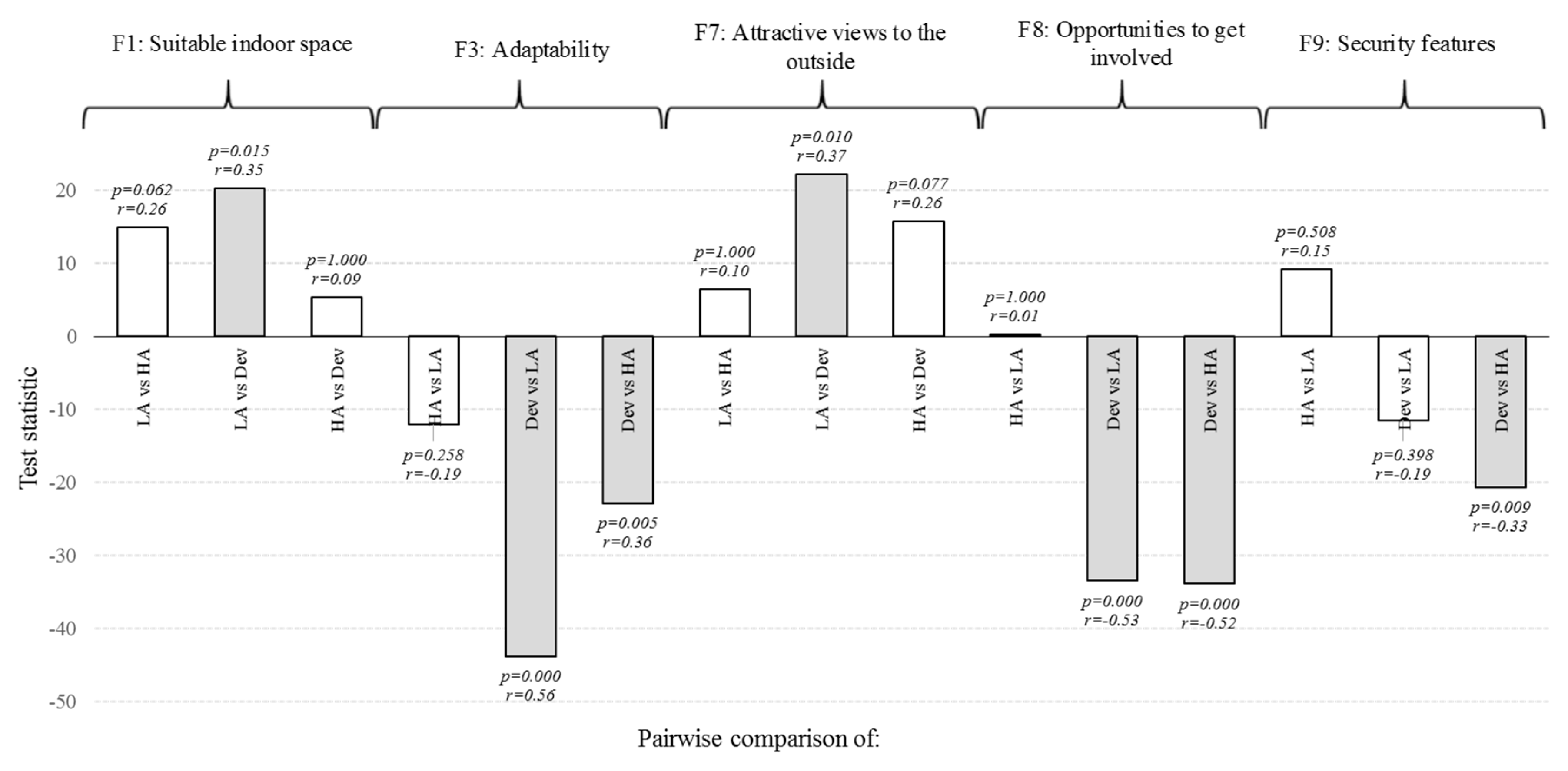

3.4.2. Housing Providers

| Criterion | Stakeholder Group | Mean Rank | Median | U-Value | Effect Size (r) | z-Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1: Suitable indoor space | Housing provider | 113.55 | 4 | 6390 | −0.07 | −1.077 | 0.281 | Retain H0 |

| Housing user | 122.05 | 5 | ||||||

| F2: Private outdoor space | Housing provider | 90.50 | 4 | 3808 | −0.41 | −6.276 | 0.000 | Reject H0 |

| Housing user | 143.04 | 5 | ||||||

| F3: Adaptability | Housing provider | 132.34 | 3 | 5282 | −0.21 | −3.206 | 0.001 | Reject H0 |

| Housing user | 104.94 | 3 | ||||||

| F4: Compatibility with architectural heritage | Housing provider | 126.08 | 3 | 5984 | −0.12 | −1.821 | 0.069 | Retain H0 |

| Housing user | 110.65 | 3 | ||||||

| F5: Features for informal socialising | Housing provider | 122.82 | 3 | 6349 | −0.07 | −1.091 | 0.275 | Retain H0 |

| Housing user | 113.61 | 3 | ||||||

| F6: Accessible public greenspace | Housing provider | 110.76 | 4 | 6078 | −0.11 | −1.638 | 0.101 | Retain H0 |

| Housing user | 124.59 | 4 | ||||||

| F7: Attractive views to outside | Housing provider | 95.64 | 3 | 4384 | −0.33 | −5.069 | 0.000 | Reject H0 |

| Housing user | 138.36 | 4 | ||||||

| F8: Opportunities to get involved | Housing provider | 133.27 | 3 | 5178 | −0.22 | −3.401 | 0.001 | Reject H0 |

| Housing user | 104.09 | 3 | ||||||

| F9: Security features | Housing provider | 132.07 | 4 | 5313 | −0.21 | −3.190 | 0.001 | Reject H0 |

| Housing user | 105.19 | 4 | ||||||

| F10: Compact neighbourhood | Housing provider | 106.46 | 2 | 5595 | −0.17 | −2.594 | 0.009 | Reject H0 |

| Housing user | 128.51 | 2 | ||||||

| F11: Proximity to amenities | Housing provider | 136.36 | 4 | 4832 | −0.27 | −4.162 | 0.000 | Reject H0 |

| Housing user | 101.28 | 3 |

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holmans, A. New Estimates of Housing Demand and Need in England, 2011 to 2031: Town & Country Planning Tomorrow Series Paper 16; Town and Country Planning Association: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). The Future Homes Commission: Building the Homes and Communities Britain Needs; RIBA: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE). Improving the Design of New Housing. What Role for Standards? CABE: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Giddings, B.; Hopwood, B.; O’Brien, G. Environment, economy and society: Fitting them together into sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochorskaite, A.; Maliene, V. Health, well-being and sustainable housing. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2013, 17, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priemus, H. How to make housing sustainable? The Dutch experience. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2005, 32, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, N. Regeneration for sustainable communities? Barriers to implementing sustainable housing in urban areas. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Mateus, R.; Bragança, L. Sustainability assessment and rating of buildings: Developing the methodology SBToolPT–H. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1962–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, D.A.; Geiser, K. A framework to guide sustainable housing development. Hous. Soc. 2010, 37, 87–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, R.L.H. Social sustainability, sustainable development, and housing, development: The experience of Hong Kong. In Housing and Social Change; Forrest, R., Lee, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 211–238. [Google Scholar]

- Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). Securing the Future—Delivering UK Sustainable Development Strategy; Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO): London, UK, 2005.

- World Conservation Union (IUCN); United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP); World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). Caring for the Earth: A Strategy for Sustainable Living; Earthscan: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, R.L.H. Socio-cultural sustainability of housing: A conceptual exploration. Hous. Theory Soc. 2004, 21, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED). Rio Declaration; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H.; Grant, M.; Guise, R. Shaping Neighbourhoods: For Local Health and Global Sustainability, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, S. Likert scales: How to (ab)use them. Med. Educ. 2004, 38, 1217–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tveit, M.S. Indicators of visual scale as predictors of landscape preference; A comparison between groups. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2882–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochorskaite, A.; Couch, R.A.; Maliene, V. Sustainable housing: A focus on “soft” impacts on health and well-being. In Proceedings of the 8th Annual Built Environment and Natural Environment (BEAN) Conference, Liverpool, UK, 6 June 2013.

- Prochorskaite, A. Assessing the Provision of “Soft” Features within New Housing Developments; The Building Futures Group: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). The Case for Space: The Size of England’s New Homes; RIBA: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE). Space in New Homes: What Residents Think; CABE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Drury, A.; Welch, G.; Allen, N. Resident Satisfaction with Space in the Home; CABE/HATC Ltd. & Ipsos MORI: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M.; Gallent, N.; Sarkar, R. Space Standards: The Benefits; CABE: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dunnett, N.; Qasim, M. Perceived benefits to human well-being of urban gardens. HortTechnology 2000, 10, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Custers, M.H.G. Gardening promotes neuroendocrine and affective restoration from stress. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neale, J.; Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). Improving Housing Quality Unlocking the Market; RIBA: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, M. Heritage-sustainability: Developing a methodology for the sustainable appraisal of the historic environment. Plan. Pract. Res. 2004, 19, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social ties and mental health. J. Urban Health 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, P.E.W.; Kemperman, A.D.A.M.; de Kleijn, B.; Borgers, A.W.J. Locations that support social activity participation of the aging population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 10432–10449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, N.; Carley, M. Sustainable Urban Neighbourhoods: Building Communities That Last; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A.; Sommerhalder, K.; Abel, T. Landscape and well-being: A scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 55, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sustainable Development Commission (SDC). Health, Place and Nature. How Outdoor Environments Influence Health and Well-Being: A Knowledge Base; SDC: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.A.; McKenzie, T.L.; Sehgal, A.; Williamson, S.; Golinelli, D.; Lurie, N. Contribution of public parks to physical activity. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, S.; Kaplan, R. Health, supportive environments, and the reasonable person model. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward Thompson, C.; Roe, J.; Aspinall, P.; Mitchell, R.; Clow, A.; Miller, D. More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; van Dillen, S.M.E.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place 2009, 15, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution. The Urban Environment; The Stationary Office: Norwich, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefoy, X. Inadequate housing and health: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 30, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. The nature of the view from home: Psychological benefits. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelata, M.J.; Ersoylu, L.; Cohen, L. Community engagement in design and planning. In Making Healthy Places: Designing and Building for Health, Well-Being and Sustainability; Dannenberg, A.L., Frumkin, H., Jackson, R.J., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc, T.; Clayton, S.; Neary, D.; Whitehead, M.; Petticrew, M.; Thomson, H.; Cummins, S.; Sowden, A.; Renton, A. Crime, fear of crime, environment, and mental health and wellbeing: Mapping review of theories and causal pathways. Health Place 2012, 18, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fish, J.S.; Ettner, S.; Ang, A.; Brown, A.F. Association of perceived neighborhood safety on body mass index. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 2296–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, D.M.; Furr, L.A.; Spine, M. The effects of neighborhood conditions on perceptions of safety. J. Crim. Justice 2002, 30, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE). What Home Buyers Want: Attitudes and Decision Making among Consumers; CABE: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, G.; Power, S. Urban form and social sustainability: The role of density and housing type. Environ. Plan. B 2009, 36, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren, K.A. Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2012, 8, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos MORI; Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). The Way We Live Now: What People Need and Expect from Their Homes; Ipsos MORI/RIBA: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos MORI; Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). Housing Standards and Satisfaction: What the Public Wants; Ipsos MORI/RIBA: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG). English Housing Survey: Households; Annual Report on England’s Households, 2012–2013; DCLG: London, UK, 2014.

- Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG). Nationally Described Space Standard—Technical Requirements; Consultation Draft; DCLG: London, UK, 2014.

- Leishman, C.; Aspinall, P.; Munro, M.; Warren, F.J. Preferences, Quality and Choice in New-Build Housing; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Coolen, H.; Meesters, J. Private and public green spaces: Meaningful but different settings. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2012, 27, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG). Code for Sustainable Homes: Technical Guide; DCLG: London, UK, 2010.

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prochorskaite, A.; Couch, C.; Malys, N.; Maliene, V. Housing Stakeholder Preferences for the “Soft” Features of Sustainable and Healthy Housing Design in the UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13010111

Prochorskaite A, Couch C, Malys N, Maliene V. Housing Stakeholder Preferences for the “Soft” Features of Sustainable and Healthy Housing Design in the UK. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2016; 13(1):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13010111

Chicago/Turabian StyleProchorskaite, Agne, Chris Couch, Naglis Malys, and Vida Maliene. 2016. "Housing Stakeholder Preferences for the “Soft” Features of Sustainable and Healthy Housing Design in the UK" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13, no. 1: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13010111

APA StyleProchorskaite, A., Couch, C., Malys, N., & Maliene, V. (2016). Housing Stakeholder Preferences for the “Soft” Features of Sustainable and Healthy Housing Design in the UK. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13010111