The Effects of Exercising in Different Natural Environments on Psycho-Physiological Outcomes in Post-Menopausal Women: A Simulation Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Evidence of Interactive Effects

1.2. Current Research

1.3. Hypotheses and Research Questions

2. Method

2.1. Participants

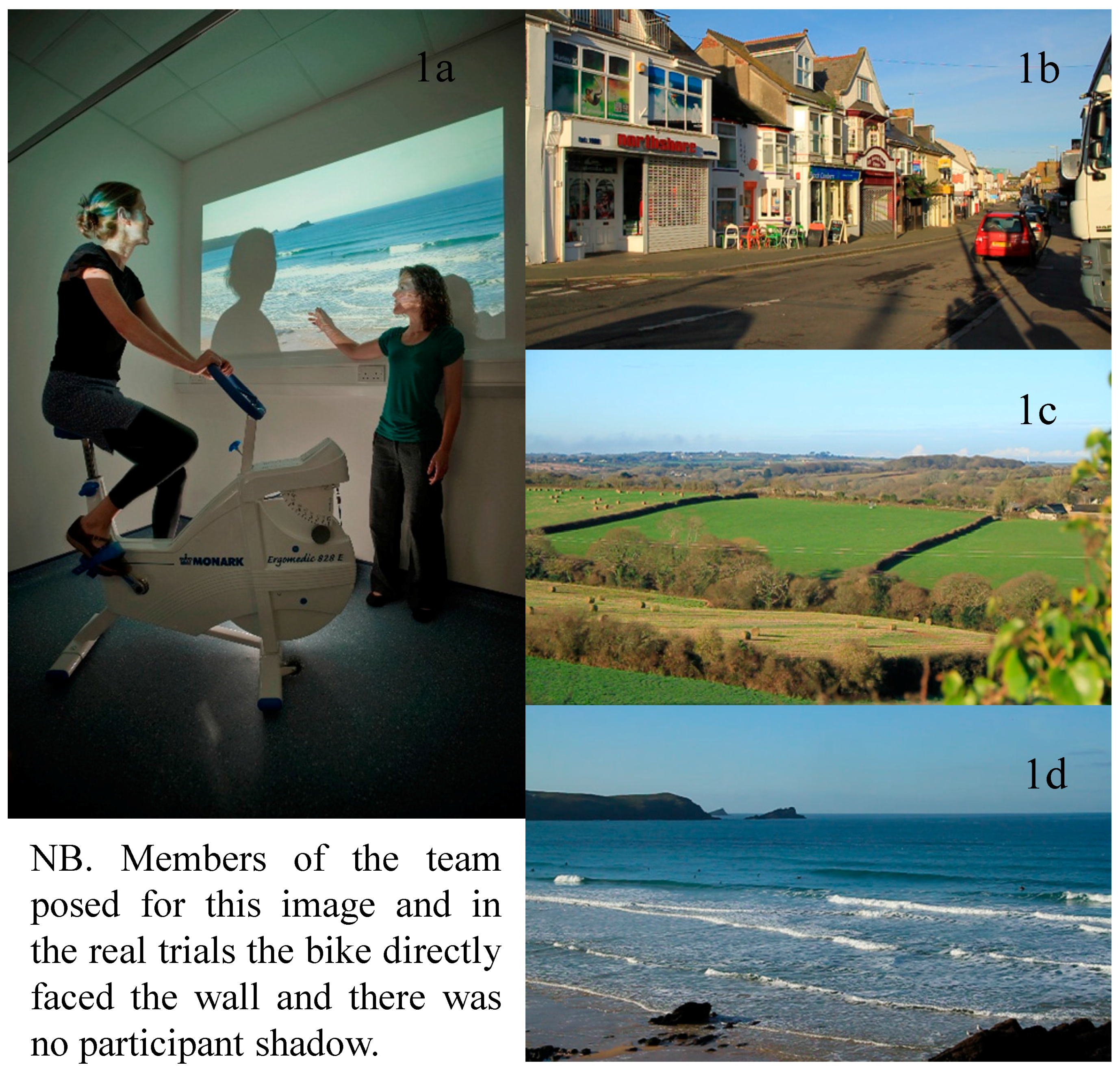

2.2. Design

2.3. Procedure and Materials

2.3.1. Recruitment and Familiarization

2.3.2. Equipment and Materials

2.4. Measures

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

| Control (Blank Wall) | Urban Video (Town) | Green Video (Countryside) | Blue Video (Coastal) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| MABP a | ||||||||

| Pre | 97.79 | 12.89 | 97.59 | 11.28 | 98.02 | 11.86 | 100.64 | 13.56 |

| Post | 98.04 | 10.54 | 94.89 | 11.82 | 95.62 | 10.81 | 96.91 | 12.53 |

| SBP b | ||||||||

| Pre | 125.00 | 17.85 | 127.92 | 16.76 | 127.08 | 18.11 | 126.95 | 18.22 |

| Post | 124.84 | 15.84 | 121.38 | 15.85 | 121.62 | 17.31 | 122.03 | 17.57 |

| DBP c | ||||||||

| Pre | 84.19 | 11.68 | 82.43 | 9.49 | 83.49 | 10.01 | 87.49 | 12.51 |

| Post | 84.65 | 9.76 | 81.65 | 10.68 | 82.62 | 8.72 | 84.35 | 10.97 |

| Heart rate | ||||||||

| Pre | 77.24 | 12.35 | 75.24 | 11.24 | 77.43 | 13.14 | 77.49 | 12.44 |

| @5 min | 101.81 | 12.76 | 97.57 | 12.49 | 100.11 | 13.94 | 101.16 | 13.61 |

| @10 min | 105.73 | 13.98 | 100.41 | 13.29 | 103.59 | 14.75 | 105.43 | 13.33 |

| @15 min | 108.31 | 14.36 | 103.38 | 14.69 | 107.49 | 16.07 | 107.86 | 14.85 |

| Post + 5 min | 80.11 | 11.49 | 79.08 | 9.13 | 80.78 | 11.84 | 79.16 | 11.98 |

| Control (Blank Wall) | Urban Video (Town) | Green Video (Countryside) | Blue Video (Coastal) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Feelings Scale | ||||||||

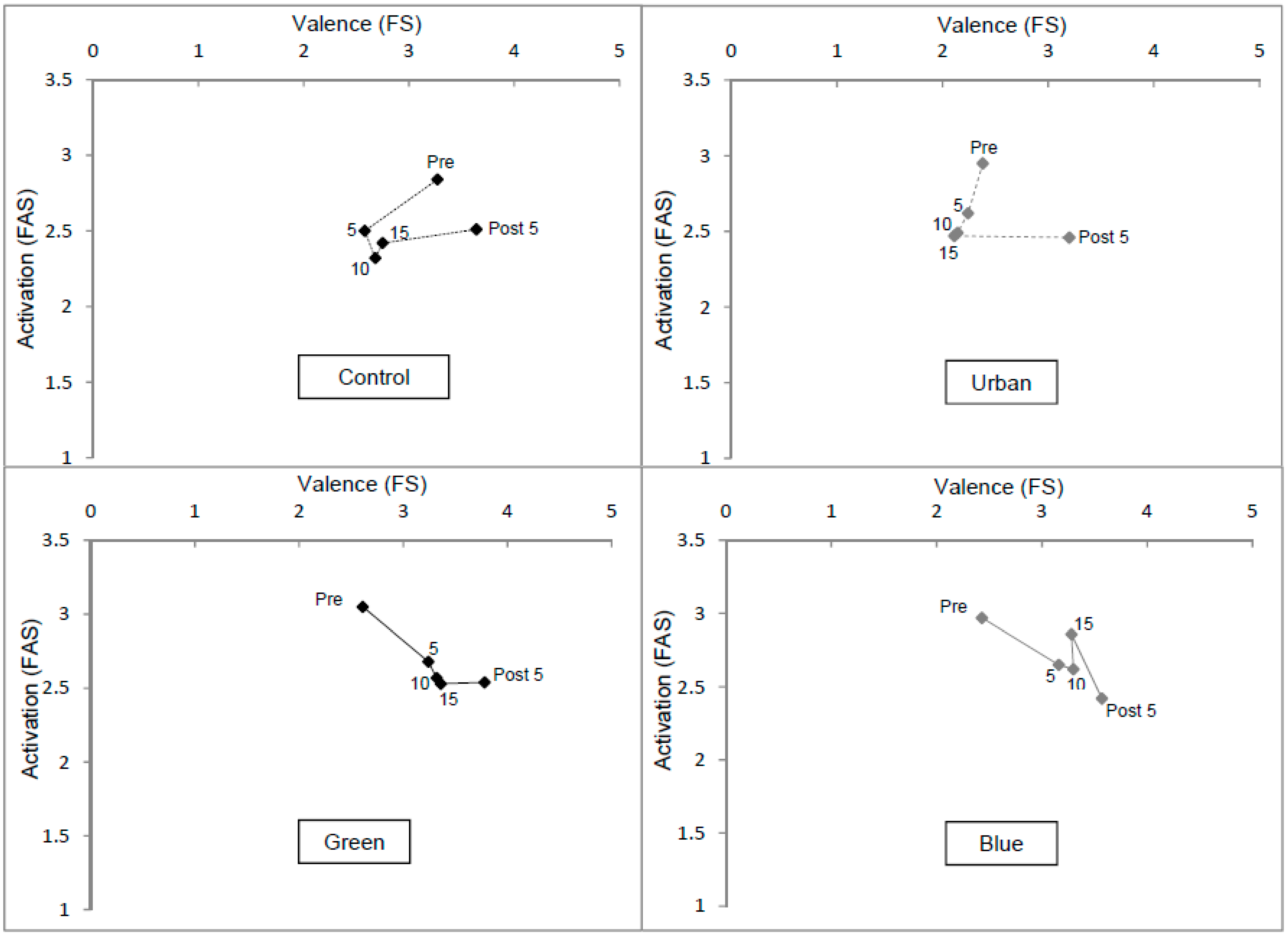

| Pre | 3.27 | 1.46 | 2.38 | 1.74 | 2.61 | 1.85 | 2.43 | 1.83 |

| @5 min | 2.58 | 1.75 | 2.24 | 1.42 | 3.24 | 1.19 | 3.16 | 1.39 |

| @10 min | 2.68 | 1.56 | 2.14 | 1.60 | 3.32 | 1.16 | 3.30 | 1.23 |

| @15 min | 2.75 | 1.56 | 2.11 | 1.65 | 3.36 | 1.46 | 3.28 | 1.55 |

| Post + 5 min | 3.64 | 1.18 | 3.20 | 1.20 | 3.78 | 0.92 | 3.57 | 1.17 |

| Felt Arousal | ||||||||

| Pre | 2.84 | 1.07 | 2.95 | 1.00 | 3.05 | 1.08 | 2.97 | 1.09 |

| @5 min | 2.50 | 0.93 | 2.62 | 0.86 | 2.68 | 1.06 | 2.65 | 0.95 |

| @10 min | 2.32 | 0.92 | 2.49 | 1.15 | 2.57 | 1.21 | 2.62 | 1.09 |

| @15 min | 2.42 | 1.16 | 2.47 | 1.00 | 2.53 | 1.30 | 2.86 | 1.36 |

| Post + 5 min | 2.51 | 1.17 | 2.46 | 0.96 | 2.54 | 0.99 | 2.42 | 1.28 |

| Time Perception | ||||||||

| @5 min | 5.42 | 1.73 | 5.61 | 2.38 | 5.61 | 2.93 | 4.84 | 1.63 |

| @10 min | 10.95 | 2.32 | 10.84 | 4.11 | 10.97 | 3.44 | 9.68 | 2.62 |

| @15 min | 17.22 | 5.39 | 15.81 | 5.79 | 16.81 | 5.30 | 14.76 | 4.28 |

| Mean during | 11.12 | 2.85 | 10.75 | 3.84 | 11.05 | 3.47 | 9.76 | 2.49 |

| RPE a | ||||||||

| @5 min | 11.62 | 1.48 | 11.70 | 1.66 | 11.57 | 1.59 | 11.68 | 1.62 |

| @10 min | 11.92 | 1.67 | 12.14 | 1.84 | 12.22 | 1.97 | 11.96 | 1.38 |

| @15 min | 12.28 | 1.70 | 12.27 | 2.08 | 12.42 | 1.63 | 12.49 | 1.59 |

| Evaluation | ||||||||

| Enjoyed | 3.18 | 1.44 | 3.41 | 1.67 | 4.49 | 1.37 | 4.95 | 1.05 |

| Feel better | 3.49 | 1.59 | 3.78 | 1.70 | 4.62 | 1.42 | 4.59 | 1.40 |

| Repeat | 3.76 | 1.40 | 3.86 | 1.80 | 4.81 | 1.43 | 5.30 | 0.77 |

| (Combined) | 3.47 | 1.34 | 3.68 | 1.54 | 4.64 | 1.25 | 4.95 | 0.94 |

3.1. Mean Arterial Blood Pressure (MABP)

| Overall | Urban vs. Control | Green vs. Control | Blue vs. Control | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (df) | F | P | pη2 | (df) | F | P | pη2 | (df) | F | P | pη2 | (df) | F | P | pη2 | |

| MABP | ||||||||||||||||

| Time | (1,36) | 12.59 | 0.001 | 0.26 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Environment | (3,108) | 1.53 | 0.210 | 0.04 | (1,36) | 1.84 | 0.184 | 0.05 | (1,36) | 0.83 | 0.370 | 0.02 | (1,36) | 0.34 | 0.562 | 0.01 |

| T × E | (3,108) | 2.34 | 0.077 | 0.06 | (1,36) | 3.44 | 0.072 | 0.09 | (1,36) | 3.55 | 0.068 | 0.09 | (1,36) | 6.70 | 0.014 | 0.16 |

| SBP | ||||||||||||||||

| Time | (1,36) | 20.95 | <0.001 | 0.37 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Environment | (3,108) | 0.04 | 0.991 | 0.00 | (1,36) | 0.02 | 0.882 | 0.00 | (1,36) | 0.10 | 0.758 | 0.00 | (1,36) | 0.05 | 0.826 | 0.00 |

| T × E | (3,108) | 2.29 | 0.083 | 0.06 | (1,36) | 5.54 | 0.024 | 0.13 | (1,36) | 4.90 | 0.033 | 0.12 | (1,36) | 3.28 | 0.079 | 0.08 |

| DBP | ||||||||||||||||

| Time | (1,36) | 2.78 | 0.104 | 0.07 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Environment | (3,108) | 3.98 | 0.010 | 0.10 | (1,36) | 4.81 | 0.035 | 0.12 | (1,36) | 1.54 | 0.223 | 0.04 | (1,36) | 1.10 | 0.302 | 0.03 |

| T × E | (3,108) | 1.73 | 0.166 | 0.05 | (1,36) | 0.70 | 0.408 | 0.02 | (1,36) | 0.74 | 0.394 | 0.02 | (1,36) | 4.72 | 0.036 | 0.12 |

| Heart rate | ||||||||||||||||

| Time | (4,136) | 289.33 | <0.001 | 0.90 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Pre–5 min | (1,34) | 281.95 | <0.001 | 0.90 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 5–10 min | (1,34) | 85.89 | <0.001 | 0.72 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 10–15 min | (1,34) | 42.00 | <0.001 | 0.55 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 15 min–Post | (1,34) | 384.34 | <0.001 | 0.92 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Environment | (3,102) | 3.98 | 0.010 | 0.06 | (1,34) | 4.60 | 0.039 | 0.12 | (1,34) | 0.22 | 0.643 | 0.01 | (1,34) | 0.31 | 0.581 | 0.01 |

| T × E | (12,408) | 2.28 | 0.084 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Pre–5 min × E | - | - | - | (1,34) | 4.29 | 0.046 | 0.11 | (1,34) | 2.05 | 0.161 | 0.06 | (1,34) | 0.56 | 0.458 | 0.02 | |

| 5–10 min × E | - | - | - | (1,34) | 2.61 | 0.115 | 0.07 | (1,34) | 0.32 | 0.573 | 0.01 | (1,34) | 0.24 | 0.627 | 0.01 | |

| 10–15 min × E | - | - | - | (1,34) | 1.21 | 0.282 | 0.03 | (1,34) | 2.17 | 0.150 | 0.06 | (1,34) | 0.04 | 0.838 | 0.00 | |

| 15 min–Post × E | - | - | - | (1,34) | 7.30 | 0.011 | 0.18 | (1,34) | 1.74 | 0.196 | 0.05 | (1,34) | 0.16 | 0.695 | 0.01 | |

| Overall | Urban vs. Control | Green vs. Control | Blue vs. Control | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (df) | F | P | pη2 | (df) | F | P | pη2 | (df) | F | P | pη2 | (df) | F | P | pη2 | |

| Feelings scale | ||||||||||||||||

| Time | (4,140) | 13.82 | <0.001 | 0.28 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Pre–5 min | (1,35) | 1.62 | 0.211 | 0.04 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 5–10 min | (1,35) | 0.09 | 0.763 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 10–15 min | (1,35) | 0.04 | 0.852 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 15 min–Post | (1,35) | 33.80 | <0.001 | 0.49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Environment | (3,105) | 5.18 | 0.002 | 0.13 | (1,34) | 6.65 | 0.014 | 0.16 | (1,35) | 1.38 | 0.248 | 0.04 | (1,35) | 0.26 | 0.613 | 0.01 |

| T × E | (12,420) | 4.35 | <0.001 | 0.11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Pre–5 min × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 4.39 | 0.043 | 0.11 | (1,35) | 16.47 | <0.001 | 0.32 | (1,35) | 15.46 | <0.001 | 0.31 | |

| 5–10 min × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 0.18 | 0.674 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 0.03 | 0.876 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 0.02 | 0.888 | 0.00 | |

| 10–15 min × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 0.42 | 0.521 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 0.07 | 0.793 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 0.20 | 0.660 | 0.01 | |

| 15 min–Post × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 0.84 | 0.365 | 0.02 | (1,35) | 2.74 | 0.107 | 0.07 | (1,35) | 5.81 | 0.021 | 0.14 | |

| Felt arousal | ||||||||||||||||

| Time | (4,140) | 5.78 | <0.001 | 0.14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Pre–5 min | (1,35) | 9.18 | 0.005 | 0.21 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 5–10 min | (1,35) | 1.92 | 0.175 | 0.05 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 10–15 min | (1,35) | 0.72 | 0.402 | 0.02 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 15 min–Post | (1,35) | 0.60 | 0.445 | 0.02 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Environment | (3,105) | 0.62 | 0.604 | 0.02 | (1,34) | 0.38 | 0.541 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 1.13 | 0.295 | 0.03 | (1,35) | 1.93 | 0.175 | 0.05 |

| T × E | (12,420) | 0.81 | 0.638 | 0.02 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Pre–5 min × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 0.05 | 0.823 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 0.05 | 0.831 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 0.01 | 0.956 | 0.00 | |

| 5–10 min × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 0.01 | 0.936 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 0.21 | 0.650 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 0.83 | 0.368 | 0.02 | |

| 10–15 min × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 0.44 | 0.510 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 0.48 | 0.492 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 1.04 | 0.314 | 0.03 | |

| 15 min-Post × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 0.06 | 0.814 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 0.14 | 0.715 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 4.76 | 0.036 | 0.12 | |

| Perceived time | ||||||||||||||||

| Time | (2,70) | 428.16 | <0.001 | 0.92 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 5–10 min | (1,35) | 885.97 | <0.001 | 0.96 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 10–15 min | (1,35) | 210.59 | <0.001 | 0.86 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Environment | (3,105) | 2.73 | 0.048 | 0.07 | (1,35) | 0.41 | 0.528 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 0.01 | 0.911 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 9.37 | 0.004 | 0.21 |

| T × E | (6,120) | 1.55 | 0.162 | 0.04 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 5–10 min × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 0.18 | 0.677 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 0.04 | 0.848 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 3.40 | 0.074 | 0.09 | |

| 10–15 min × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 3.50 | 0.070 | 0.09 | (1,35) | 0.41 | 0.526 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 3.65 | 0.064 | 0.10 | |

| PRE | ||||||||||||||||

| Time | (2,70) | 23.81 | <0.001 | 0.41 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 5–10 min | (1,35) | 13.99 | 0.001 | 0.29 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 10–15 min | (1,35) | 23.99 | <0.001 | 0.41 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Environment | (3,105) | 0.09 | 0.964 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 0.08 | 0.076 | 0.00 | (1,35) | 0.35 | 0.556 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 0.09 | 0.763 | 0.00 |

| T × E | (6,210) | 0.75 | 0.609 | 0.02 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 5–10 min × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 0.31 | 0.581 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 1.54 | 0.222 | 0.04 | (1,35) | 0.18 | 0.673 | 0.01 | |

| 10–15 min × E | - | - | - | (1,35) | 0.48 | 0.492 | 0.01 | (1,35) | 0.57 | 0.454 | 0.02 | (1,35) | 0.95 | 0.337 | 0.03 | |

| Evaluation | ||||||||||||||||

| Enjoyed | (3,108) | 17.05 | <0.001 | 0.32 | (1,36) | 0.56 | 0.457 | 0.02 | (1,36) | 19.12 | <0.001 | 0.35 | (1,36) | 46.75 | <0.001 | 0.57 |

| Feel better | (3,108) | 6.52 | <0.001 | 0.15 | (1,36) | 0.01 | 0.920 | 0.00 | (1,36) | 8.72 | 0.006 | 0.20 | (1,36) | 7.36 | 0.010 | 0.17 |

| Repeat | (3,108) | 15.07 | <0.001 | 0.30 | (1,36) | 1.23 | 0.274 | 0.03 | (1,36) | 17.96 | <0.001 | 0.33 | (1,36) | 43.82 | <0.001 | 0.55 |

| (Combined) | (3,108) | 16.24 | <0.001 | 0.31 | (1,36) | 0.66 | 0.423 | 0.02 | (1,36) | 19.36 | <0.001 | 0.35 | (1,36) | 35.40 | <.001 | 0.50 |

3.2. Heart Rate

3.3. Affective Responses

3.4. Time Perception

3.5. Perceived Level of Exertion (RPE)

3.6. Evaluations and Willingness to Repeat

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Results

4.2. Accounting for the Effects

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

4.4. Conclusions and Implications

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Conflicts of interest

References

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Mutrie, N. Psychology of Physical Activity: Determinants, Well-Being and Interventions; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2012). Walking and cycling: Local measures to promote walking and cycling as forms of travel. NICE Public Health Guidance 41. Available online: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/PHG/Published (accessed on 6 October 2014).

- Humpel, N.; Owen, N.; Iverson, D.; Leslie, E.; Bauman, A. Perceived environment attributes, residential location and walking for particular purposes. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 26, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, S.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Natural environments—Healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environ. Plan A 2003, 35, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Schellevis, F.G.; Groenewegen, P.P. Morbidity is related to a green living environment. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R.; Popham, F. Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: An observational population study. Lancet 2008, 372, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Wheeler, B.W.; Depledge, M.H. Coastal proximity and health: A fixed effects analysis of longitudinal panel data. Health Place 2013, 23, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Hargreaves, E.A.; Parfitt, G. Introduction to special section on affective responses to exercise. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 749–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Hargreaves, E.A.; Parfitt, G. Invited Guest Editorial: Envisioning the next fifty years of research on the exercise—Affect relationship. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Peacock, J.; Sellens, M.; Griffin, M. The mental and physical health outcomes of green exercise. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2005, 15, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson Coon, J.; Boddy, K.; Stein, K.; Whear, R.; Barton, J.; Depledge, M.H. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.A. Landscape planning and stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2003, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environments. In Behaviour and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward Thompson, C.; Roe, J.; Aspinall, P.; Mitchell, R.; Clow, A.; Miller, D. More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2012, 105, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health. Health Survey for England 2004; Department of Health: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Thompson, C.W.; Travlou, P. Contested views of freedom and control: Children, teenagers and urban fringe woodlands in Central Scotland. Urban For. Urban Green. 2003, 2, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. Adolescents and the natural environment: A time out. In Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations; Kahn, P.H., Kellert, S.R., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 227–257. [Google Scholar]

- Focht, B.C. Brief walks in outdoor and laboratory environments: Effects on affective responses, enjoyment, and intentions to walk for exercise. Brief Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2009, 80, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Gärling, T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Hall, E.E.; Van Landuyt, L.M.; Petruzzello, S.J. Walking in (affective) circles: Can short walks enhance affect? J. Behav. Med. 2000, 23, 245–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.A.; Eklund, R.C. Assessing flow in physical activity: The Flow State Scale-2 and Dispositional Flow Scale-2. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2002, 24, 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Droit-Volet, S.; Meck, W.H. How emotions colour our perception of time. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, G.A.V. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Backhouse, S.H.; Gray, C.; Lind, E. Walking is popular among adults but is it pleasant? A framework for clarifying the link between walking and affect as illustrated in two studies. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 246–264. [Google Scholar]

- Aspinall, P.A.; Thompson, W.C.; Alves, S.; Sugiyama, T.; Vickers, A.; Brice, R. Preference and relative importance for environmental attributes of neighbourhood open space in older people. Environ. Plann. B Plann. Des. 2010, 37, 1022–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbank, P.M.; Riebe, D. Promoting Exercise and Behavior Change in Older Adults; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Focht, B.C. Affective responses to 10-minute and 30-minute walks in sedentary, overweight women: Relationships with theory-based correlates of walking for exercise. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teas, J.; Hurley, T.; Ghumare, S.; Ogoussan, K. Walking outside improves mood for healthy postmenopausal women. Clin. Med. Oncol. 2007, 1, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- White, M.P.; Smith, A.; Humphryes, K.; Pahl, S.; Snelling, D.; Depledge, M.H. Blue Space: The importance of water for preferences, affect and restorativeness ratings of natural and built scenes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Pahl, S.; Ashbullby, K.; Herbert, S.; Depledge, M.H. Feelings of restoration from recent nature visits. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.; Smith, B.; Stoker, L.; Bellew, B.; Booth, M. Geographical influences upon physical activity participation: Evidence of a ‘coastal effect’. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 1999, 23, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Herbert, S.; Alcock, I.; Depledge, M.H. Coastal proximity and physical activity. Is the coast an underappreciated public health resource? Prev. Med. 2014, 69, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, B.; White, M.P.; Stahl-Timmins, W.; Depledge, M.H. Does living by the coast improve health and wellbeing? Health Place 2012, 18, 1198–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gascon, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Martinez, D.; Dadvand, P.; Forns, J.; Plasencia, A.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 4354–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasliva, S.G.; Guidetti, L.; Buzzachera, C.; Elsangedy, H.; Krinski, K.; De Campos, W.; Goss, F.L.; Baldari, C. Psycho-physiological responses to self-paced treadmill and overground exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 6, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, J.; Fujiyama, H.; Sugano, A.; Okamura, T.; Chang, M.; Onouha, F. Psychological responses to exercising in laboratory and natural environments. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2006, 7, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depledge, M.H.; Stone, R.J.; Bird, W.J. Can natural and virtual environments be used to promote improved human health and wellbeing? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 4660–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, G.; Neill, J. The effect of “green exercise” on state anxiety and the role of exercise duration, intensity, and greenness: A quasi-experimental study. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, A.; Barton, J.; Cossey, R.; Gainsford, P.; Griffin, M.; Micklewright, D. Visual color perception in green exercise: Positive effects on mood and perceived exertion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 8661–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, C.J.; Rejeski, W.J. Not what, but how one feels: The measurement of affect during exercise. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1989, 11, 304–317. [Google Scholar]

- Svebak, S.; Murgatroyd, S. Metamotivational dominance: A multimethod validation of reversal theory constructs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohs, K.D.; Schmeichel, B.J. Self-regulation and extended now: Controlling the self alters the subjective experience of time. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogerson, M.; Brown, D.K.; Sandercock, G.; Wooller, J.-J.; Barton, J. A comparison of four typical green exercise environments and predictions of psychological health outcomes. Perspec. Public Health 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Jeong, G.W.; Baek, H.S.; Kim, G.W.; Sundaram, T.; Kang, H.K.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, H.J.; Song, J.K. Human brain activation in response to visual stimulation with natural and built scenery pictures: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 2600–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, R.D.; Chua, P.M.; Dolan, R.J. Common effects of emotional valence, arousal and attention on neural activation during visual processing of pictures. Neuropsychologia 1999, 37, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.M.; Dunsiger, S.; Ciccolo, J.T.; Lewis, B.A.; Albrecht, A.E.; Marcus, B.H. Acute affective responses to a moderate-intensity exercise stimulus predicts physical activity participation 6 and 12 months later. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staats, H.; Hartig, T. Alone or with a friend: A social context for psychological restoration and environmental preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; Van Dillen, S.M.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place 2009, 15, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, P.; Tzoulas, J.P.K.; Adams, M.D.; Barber, A.; Box, J.; Breuste, J.; Elmqvist, T.; Frith, M.; Gordon, C.; Greening, K.L.; et al. Towards an integrated understanding of green space in the European built environment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, M.; Vohs, K.D.; Aaker, J. Awe expands people’s perception of time, alters decision making, and enhances well-being. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamps, A.E. Use of photographs to simulate environments: A meta-analysis. Percept. Mot. Skills 1990, 71, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Takayama, N.; Park, B.J.; Li, Q.; Song, C.; Komatsu, M.; Ikei, H.; Tyrväinen, L.; Kagawa, T.; et al. Influence of forest therapy on cardiovascular relaxation in young adults. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, A.A.; Deuster, P.A.; Francis, J.L.; Beadling, C.; Kop, W.J. The role of depression in short-term mood and fatigue responses to acute exercise. Int. J. Behave. Med. 2010, 17, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depledge, M.H.; Bird, W.J. The blue gym: Health and well-being from our coasts. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 947–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, J.; Pretty, J.; Macdonald, D.W. Nature as a source of health and well-being: Is this an ecosystem service that could pay for conserving biodiversity? Key Top. Conserv. Biol. 2013, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Barton, J.; Colbeck, I.; Hine, R.; Mourato, S.; Mackerron, G.; Wood, C. Health values from ecosystems. In The UK National Ecosystem Assessment Technical Report; UK National Ecosystem Assessment: Cambridge, UK, 2011; Chapter 23. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

White, M.P.; Pahl, S.; Ashbullby, K.J.; Burton, F.; Depledge, M.H. The Effects of Exercising in Different Natural Environments on Psycho-Physiological Outcomes in Post-Menopausal Women: A Simulation Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 11929-11953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911929

White MP, Pahl S, Ashbullby KJ, Burton F, Depledge MH. The Effects of Exercising in Different Natural Environments on Psycho-Physiological Outcomes in Post-Menopausal Women: A Simulation Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015; 12(9):11929-11953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911929

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhite, Mathew P., Sabine Pahl, Katherine J. Ashbullby, Francesca Burton, and Michael H. Depledge. 2015. "The Effects of Exercising in Different Natural Environments on Psycho-Physiological Outcomes in Post-Menopausal Women: A Simulation Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 9: 11929-11953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911929

APA StyleWhite, M. P., Pahl, S., Ashbullby, K. J., Burton, F., & Depledge, M. H. (2015). The Effects of Exercising in Different Natural Environments on Psycho-Physiological Outcomes in Post-Menopausal Women: A Simulation Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(9), 11929-11953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911929