Travel Behavior Change in Older Travelers: Understanding Critical Reactions to Incidents Encountered in Public Transport

Abstract

:1. Introduction

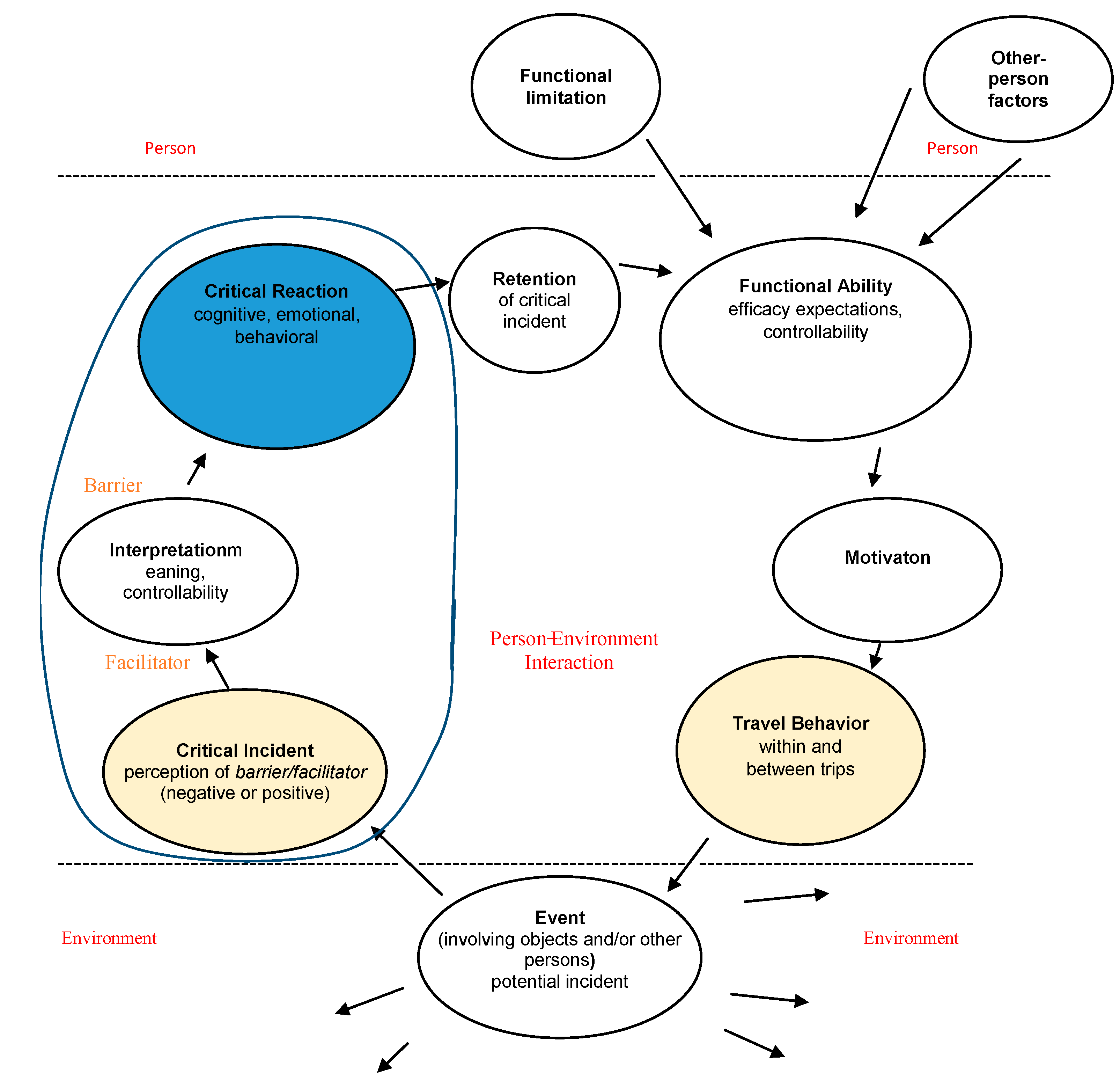

2. Research Problem

- How do critical reactions (i.e., cognitions, emotions, and behavior) to critical incidents encountered in public transport contribute to the older traveler’s process of travel behavior change?

- How should older travelers’ critical reactions be understood, theoretically, in a cognitive and behavioral framework grounded in person–environment interaction?

3. Theoretical Framework

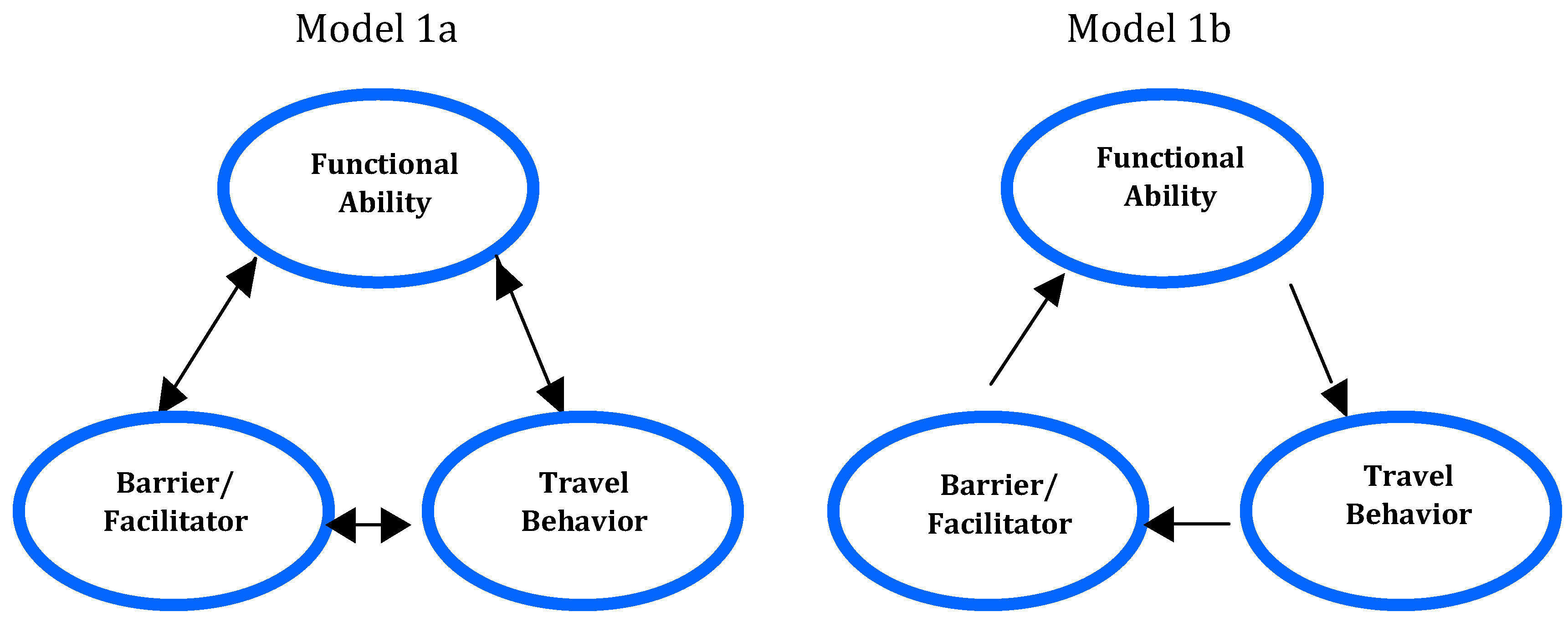

3.1. The Process of Travel-Behavior Change

3.2. Barriers and Facilitators in Public Transport Traveling

4. Method

4.1. Participants

| Functional limitation (FL) | Frequency of FL |

|---|---|

| Restricted mobility | 16 |

| Vision impairment | 13 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 10 |

| Hearing impairment | 9 |

| Chronic pain | 7 |

| Diabetes | 4 |

| Asthma, allergy, and hypersensitivity | 4 |

| Attention, memory, and concentration disability | 4 |

| Neurological disorder | 4 |

| Chest disease | 3 |

| Mental ill-health | 2 |

| Travel sickness | 2 |

| Reading, writing, or speech disability | 1 |

| Rheumatic disease | 1 |

| Sum of FL | 80 |

| No FL | 1 |

4.2. Procedure

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

| Five Critical Reaction Themes * | Three Psychological Classes of Critical Reactions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Emotional | Behavioral | |

| Firm restrictions (n = 22) | It is just not possible. | Resignation | Choose other ways of traveling |

| Unpredictability (n = 21) | What will happen? Should I travel? | Worry, insecurity, and fear | Avoid traveling Travel although afraid |

| Unfair treatment (n = 14) | It is not fair. I do not want to travel. | Anger, irritation, and humiliation | Stop traveling |

| Complicated trips (n = 19) | It is too much. | Confusion and irritation | Travel with much effort |

| Earlier adverse experiences (n = 5) | Have to be on guard. | Vigilance | Adapt travels (e.g., only daytime) |

5.1. Firm Restrictions

5.2. Unpredictability

5.3. Unfair Treatment

5.4. Complicated Trips

5.5. Earlier Adverse Experiences

5.6. Positive Critical Reactions

6. Discussion

6.1. Control

6.2. Emotion

6.3. Staff

6.4. Heterogeneity

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Number of Critical Incidents (Negative/Positive) in Travel Chain Categories | Examples of Incidents, Negative (–) and Positive (+) |

|---|---|

| 1. Ticketing (sum 17): Pricing (6, 3) | Prices vary depending on time of booking. Feeling deceived. (–) Inexpensive tickets. (+) |

| System flexibility (2, 1) | Was supposed to buy tickets on the Internet to get updated information, best price, to choose my seat. Not everyone has Internet. (–) Can pay with credit card on the phone. (+) |

| Information (4, 0) | Did not know that the train would be replaced by bus for part of the distance. If I had known, I would not have booked. (–) |

| Time and connections (1, 0) | Long waiting time for booking at station. (–) |

| 2. To and from station (sum 2): Pricing (1, 0) | Expensive parking in the daytime. Try to travel in other ways. (–) |

| Physical environment (1, 0) | Pavements not sanded. (–) |

| 3. At station (sum 18): Physical environment (12, 0) | The elevator out of order. Cannot travel by underground—what if the elevator is out of order again? (–) |

| Information (1, 0) | Difficult to find your way, poor signposting. (–) |

| Staff (4, 1) | No staff to help with luggage; impossible to travel alone. (–) The ticket collector helped me all the way to the train. Then I could manage to travel. (+) |

| 4. On and off vehicle (sum 6): Physical environment (2, 0) | Difficult to get on bus with walker and groceries; have to lift the walker. (–) |

| Staff (4, 0) | Bus driver does not use the kneeling function although I have a walker. (–) |

| 5. Onboard (sum 22): System flexibility (1, 0) | Not allowed to bring a bicycle on train, so I have to take the car into the city. (–) |

| Physical environment (13, 3) | The bus is lurching, making it difficult to cope with a stiff leg. (–) Nice environment on commuter trains and long-distance trains. Can look out and move around. (+) |

| Information (1, 0) | Train stopped. No information about the delay, the reason for it, or how long it would be. Couldn’t tell my daughter when to come and fetch me. Wondered what had happened. Stressful. (–) |

| Fellow passengers (2, 0) | Noisy school classes. Nobody tells them to be quiet. I got off. (–) |

| Staff (2, 0) | Bus driver started before I had sat down. (–) |

| 6. More than one part of trip (sum 12): | |

| Physical environment (1, 0) | Train reminds me of steam locomotives from childhood; connected to bad memories. Makes me feel sick. (–) |

| Information (1, 0) | Misinformation. I had been told that the train manager would help me but that was wrong. (–) |

| Fellow passengers (3, 0) | Avoid certain underground stations late at night. Feel unsafe if there are few persons or only men on the platform. (–) |

| Staff (1, 0) | No staff to help with luggage and walkers. Cannot travel on my own. Have problems with my back and cannot lift my case. (–) |

| Time and connections (4, 2) | Several changes of travel modes to my destination. Therefore, I use the Special Transport Service [i.e., taxi service for persons with functional limitations]. (–) |

References

- United Nations. World Population Ageing; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division of the United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Myck, M. Living longer, working longer: The need for a comprehensive approach to labour market reform in response to demographic changes. Eur. J. Ageing 2015, 12, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Sweden. Sveriges Framtida Befolkning 2012–2060: [The Future Population of Sweden 2012–2060] Örebro: SCB2012. Available online: http://www.scb.se/statistik/_publikationer/BE0401_2012I60_BR_BE51BR1202.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- Sundling, C.; Berglund, B.; Nilsson, M.E.; Emardson, R.; Pendrill, L.R. Overall accessibility to traveling by rail for the elderly with and without functional limitations: The whole-trip perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 12938–12968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwarsson, S.; Ståhl, A. Traffic engineering and occupational therapy: A collaborative approach for future directions. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 1999, 6, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Jones, A.; Roberts, H. More than A to B: The role of free bus travel for the mobility and wellbeing of older citizens in London. Ageing Soc. 2014, 34, 472–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollenkopf, H.; Hieber, A.; Wahl, H.-W. Continuity and change in older adults’ perceptions of out-of-home mobility over ten years: A qualitative-quantitative approach. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 782–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siren, A.; Hakamies-Blomqvist, L. Does gendered driving create gendered mobility? Community-related mobility in Finnish women and men aged 65+. Transp. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avineri, E. The use and potential of behavioural economics from the perspective of transport and climate change. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Fujii, S.; Friman, M.; Gärling, T. Behaviour theory and soft transport policy measures. Transp. Policy 2011, 18, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, S.; Henriksson, P. Äldres Resvanor. Äldre Trafikanter som Heterogen Grupp och Framtida Forskningsbehov. Available online: https://www.vti.se/sv/publikationer/pdf/aldres-resvanor-aldre-trafikanter-som-heterogen-grupp-och-framtida-forskningsbehov.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2015).

- Boschmann, E.E.; Brady, S. Travel behaviors, sustainable mobility, and transit-oriented developments: A travel count analysis of older adults in the Denver, Colorado metropolitan area. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive: An agentic perspective. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundling, C.; Emardson, R.; Pendrill, L.R.; Nilsson, M.E.; Berglund, B. Two models of accessibility to railway traveling for vulnerable, elderly persons. Measurement 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. The self-system in reciprocal determinism. Am. Psychol. 1978, 33, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.; Iwarsson, S.; Ståhl, A. Theoretical understanding and methodological challenges in accessibility assessments, focusing the environmental component: An example from travel chains in urban bus transport. Disabil. Rehabil. 2002, 24, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iwarsson, S.; Jensen, G.; Ståhl, A. Travel chain enabler: Development of a pilot instrument for assessment of urban public bus transport accessibility. Technol. Disabil. 2000, 12, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Risser, R.; Iwarsson, S.; Ståhl, A. How do people with cognitive functional limitaions post-stroke manage the use of buses in local public transport? Transp. Res. Part F 2012, 15, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J. Generalized Expectancies for Internal versus External Control of Reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenkvist, J.; Risser, R.; Iwarsson, S.; Ståhl, A. Exploring mobility in public environments among people with cognitive functional limitations—Challenges and implications for planning. Mobilities 2010, 5, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadalla, T.M. Determinants, correlates and mediators of psychological distress: A longitudinal study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 2199–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, C.E.; Mirowsky, J. The sense of personal control: Social structural causes and emotional consequences. In Handbook of Sociology and Mental Health, 2nd ed.; Anehensel, C.S., Phelan, J.C., Bierman, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel, W.; Shoda, Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, S.T.; Zajonc, R.B. Affect, cognition, and awareness: Affective priming with optimal and suboptimal stimulus exposures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friman, M. The structure of affective reactions to critical incidents. J. Econ. Psychol. 2004, 25, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurr, P.H.; Hedaa, L.; Geersbro, J. Interaction episodes as engines of relationship change. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E.; Mullen, S.P.; Szabo, A.N.; White, S.M.; Wójcicki, T.R.; Mailey, E.L.; Gothe, N.P.; Olson, E.A.; Voss, M.; Erickson, K.; et al. Self-regulatory processes and exercise adherence in older adults: Executive function and self-efficacy effects. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trafimow, D.; Sheeran, P.; Conner, M.; Finlay, K.A. Evidence that behavioural control is a multidimensional construct: Perceived control and perceived difficulty. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 41, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C.; Slotegraaf, G. Instrumental-reasoned and symbolic-affective motives for using a motor car. Transp. Res. Part F 2001, 4, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior; Ramachaudran, V.S., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 4, pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gärling, T.; Gillholm, R.; Gärling, A. Reintroducing attitude theory in travel behavior research: The validity of an interactive interview procedure to predict car use. Transportation 1998, 25, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgement. In Groups, Leadership and Men; Guestzkow, M.H., Ed.; Carnegie: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1951; pp. 117–190. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, S.; Gärling, T. Application of attitude theory for improved predictive accuracy of stated preference methods in travel demand analysis. Transp. Res. Part A 2003, 37, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P. Intention-behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 12, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitudes and the attitude-behavior relation: Reasoned and automatic processes. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 11, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, E.; Abraham, C. The role of affect in UK commuters’ travel mode choices: In interpretative phenomenological analysis. Br. J. Psychol. 2006, 97, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C. A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D.; Bitner, M.J. Relational benefits in service industries: The customer’s perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1998, 26, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullman, M.E.; Gross, M.A. Ability of experience design elements to elicit emotions and loyalty behaviors. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 551–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Banister, D.; Anable, J. Rethinking habits and their role in behavior change: The case of low-carbon mobility. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forward, S.E. The theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive norms and past behavior in the prediction of drivers’ intentions to violate. Transp. Res. Part F 2009, 12, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, L.; Friman, M.; Gärling, T.; Hartig, T. Quality attributes of public transport that attract car users: A research review. Transp. Policy 2013, 25, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirão, G.; Sarsfield Cabral, J.A. Understanding attitudes towards public transport and private car: A qualitative study. Transp. Policy 2007, 14, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eboli, L.; Mazzulla, G. How to capture the passengers’ point of view on a transit service through rating and choice options. Transp. Rev. 2010, 30, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellesson, M.; Friman, M. Perceived satisfaction with public transport service in nine European cities. J. Transp. Res. Forum 2008, 47, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friman, M.; Gärling, T. Frequency of negative critical incidents and satisfaction with public transport services II. J. Retail.Consum. Servi. 2001, 8, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Stopher, P.; Bullock, P. Service quality. Developing a service quality index in the provision of commercial bus contracts. Transp. Res. Part A 2003, 37, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. Communication and control processes in the delivery of service quality. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, B. Tjänsteutveckling Med Inbyggd Kvalitet [Service Development with In-Built Quality]; Karlstad Research Center: Karlstad, Sweden, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anable, J.; Gatersleben, B. All work and no play? The role of instrumental and affective factors in work and leisure journeys by different travel modes. Transp. Res. Part A 2005, 39, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundling, C.; Nilsson, M.E.; Hellqvist, S.; Pendrill, L.; Emardson, R.; Berglund, B. Travel behavior change in old age: The role of critical incidents in public transport. 2015; (submitted). [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, J.C. The Critical Incident Technique. Psychol. Bull. 1954, 51, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitner, M.J.; Booms, B.H.; Stanfield Tetreault, M. The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball sampling. Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Soc. Methods Res. 1981, 10, 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, L.D.; Borgen, W.A.; Amundson, N.E.; Maglio, A-S.T. Fifty Years of the critical incident technique: 1954–2004 and beyond. Qual. Res. 2005, 5, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremler, D.D. The critical incident technique in service research. J. Serv. Res. 2004, 7, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psych. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkvist, J. Mobility in Public Environments and Use of Public Transport. Available online: http://tftnts1.tft.lth.se/publ/3000/bull239JRscr.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2015).

- Su, F.; Bell, M.G.H. Transport for older people: Characteristics and solutions. Res. Transp. Econ. 2009, 25, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, B.; Roos, I. Critical incident techniques. Towards a framework for analyzing the criticality of critical incidents. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2001, 12, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, K. Kvarboende Eller Flyttning På Äldre Dagar—En Kunskapsöversikt; Rapport 2006:9; Stiftelsen Stockholm Gerontology Research Center: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shergold, I.; Lyons, G.; Hubers, C. Future mobility in an ageing society—Where are we heading? J. Transp. Health 2014, 2, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sundling, C. Travel Behavior Change in Older Travelers: Understanding Critical Reactions to Incidents Encountered in Public Transport. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14741-14763. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121114741

Sundling C. Travel Behavior Change in Older Travelers: Understanding Critical Reactions to Incidents Encountered in Public Transport. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015; 12(11):14741-14763. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121114741

Chicago/Turabian StyleSundling, Catherine. 2015. "Travel Behavior Change in Older Travelers: Understanding Critical Reactions to Incidents Encountered in Public Transport" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 11: 14741-14763. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121114741

APA StyleSundling, C. (2015). Travel Behavior Change in Older Travelers: Understanding Critical Reactions to Incidents Encountered in Public Transport. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(11), 14741-14763. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121114741