Changing Patterns of Health in Communities Impacted by a Bioenergy Project in Northern Sierra Leone

Abstract

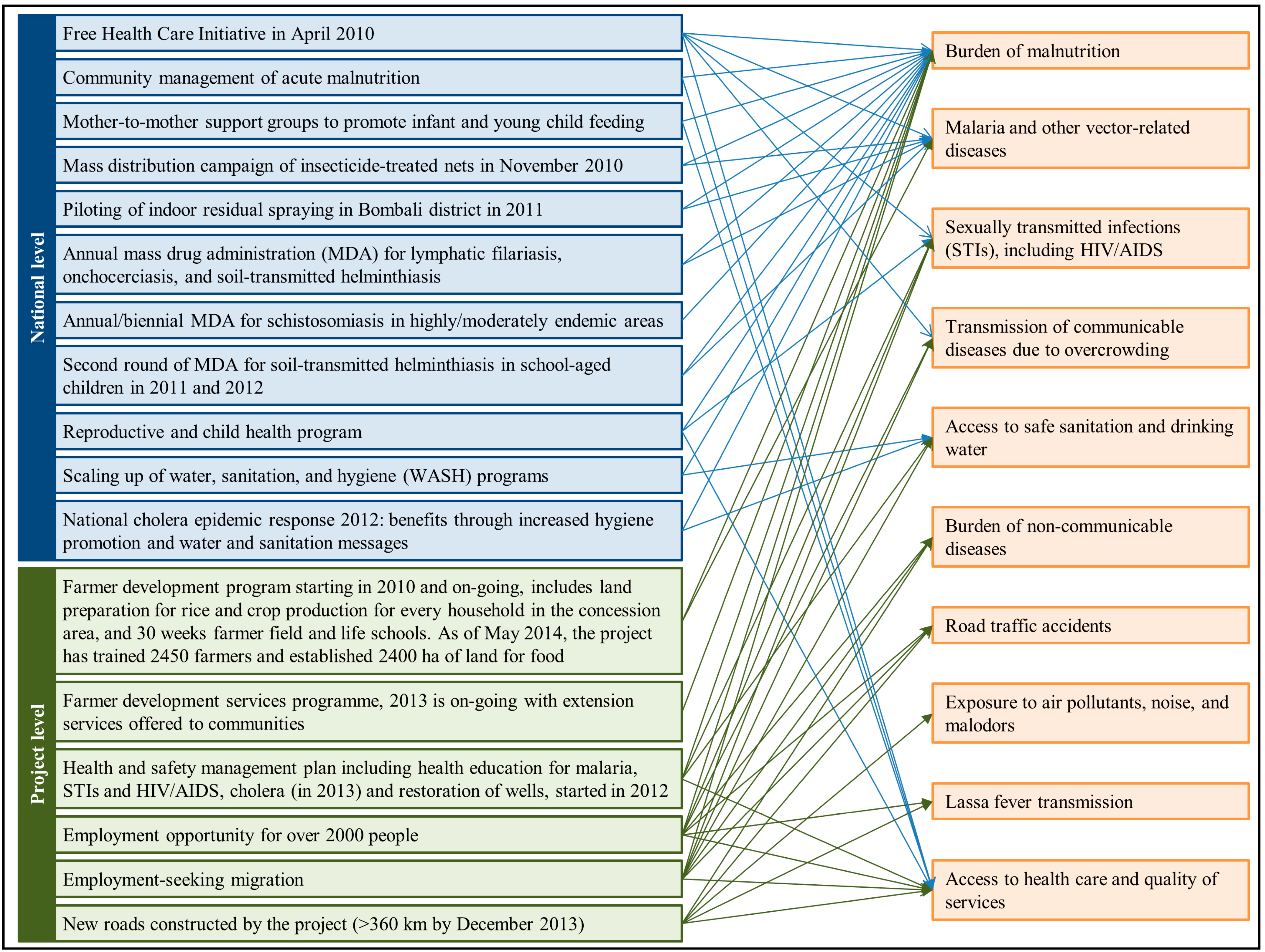

:1. Introduction

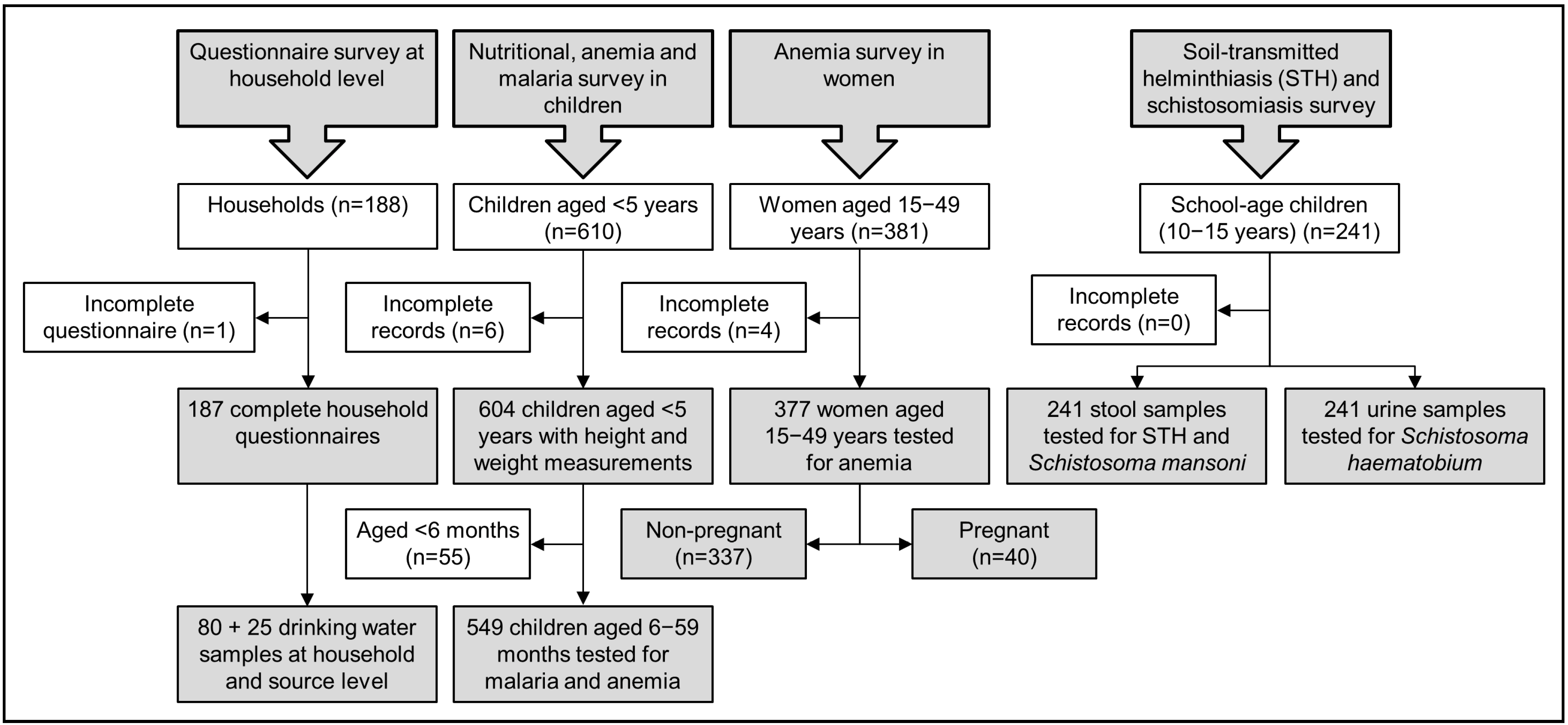

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

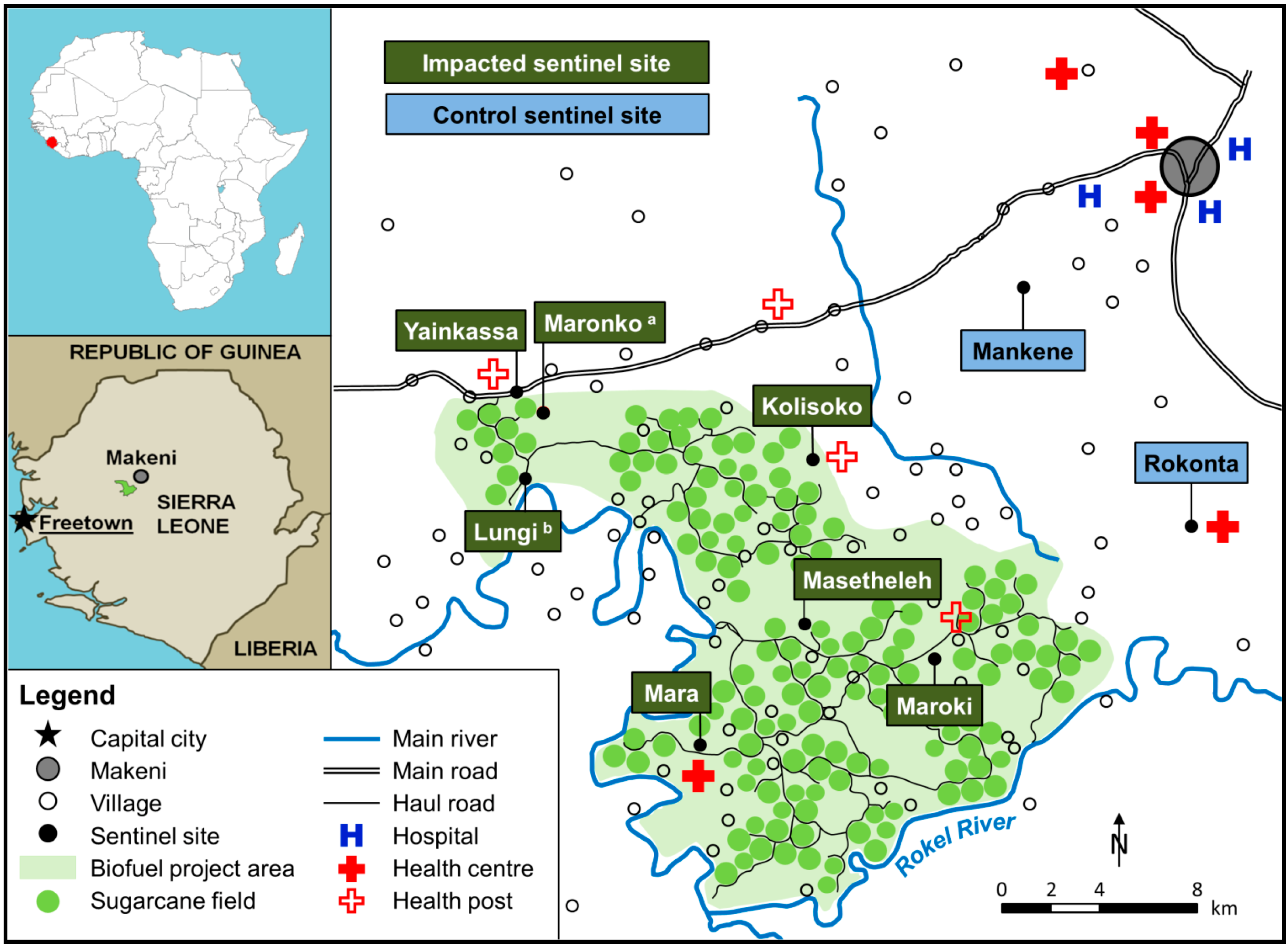

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Study Design and Sampling Methodology

2.4. Statistical Analysis

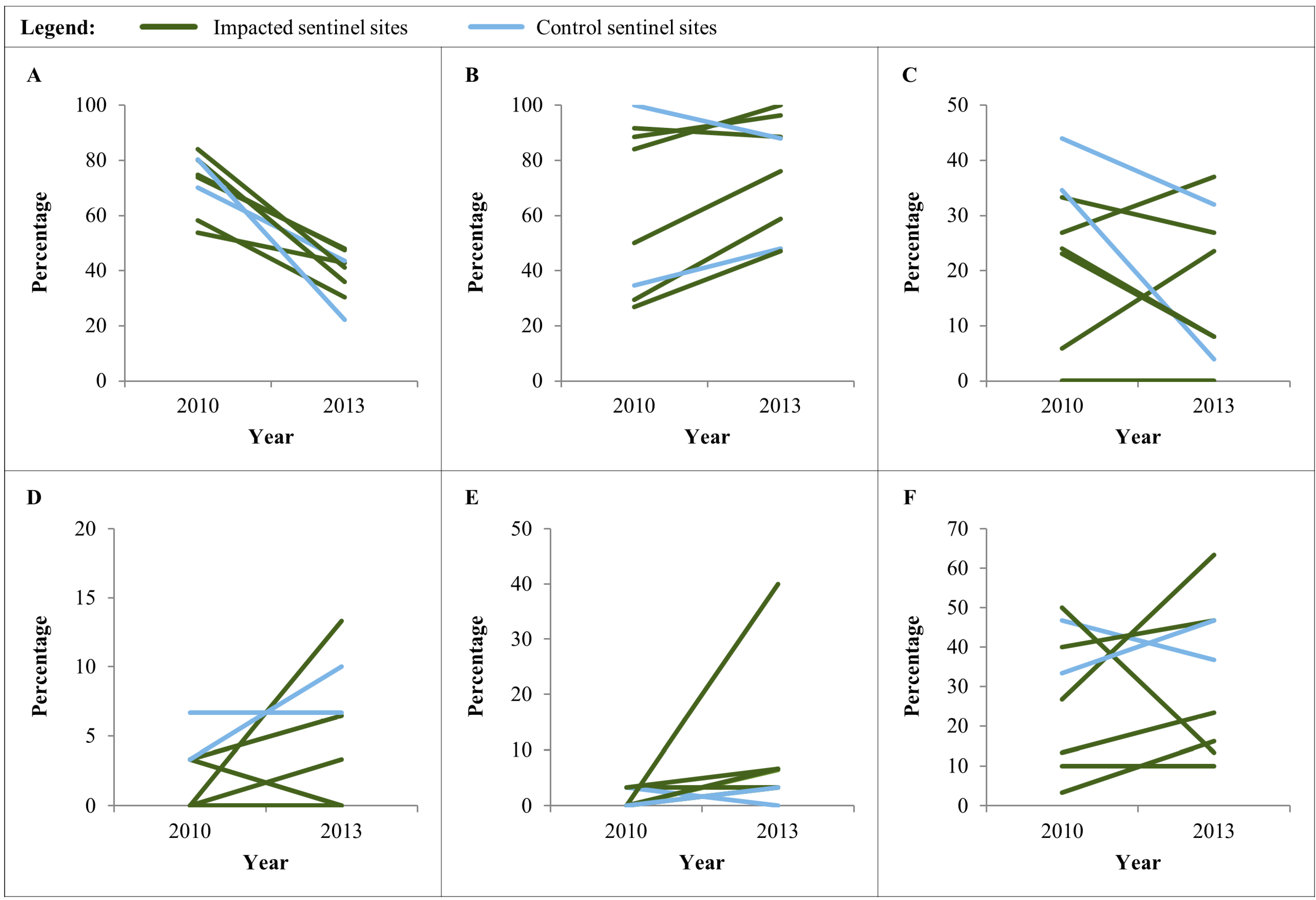

3. Results

3.1. Study Compliance

| Characteristics | Impacted Sentinel Sites | Control Sentinel Sites | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2013 | 2010 | 2013 | |

| Sentinel sites | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| Households | 143 | 137 | 51 | 50 |

| Children aged <59 months | 421 | 390 | 164 | 214 |

| Children aged 6–59 months | 409 | 350 | 161 | 199 |

| School-going children aged 10–15 years | 180 | 181 | 60 | 60 |

| Women aged 15–49 years | 284 | 255 | 113 | 122 |

| Non-pregnant | 234 | 230 | 97 | 107 |

| Pregnant | 50 | 25 | 16 | 15 |

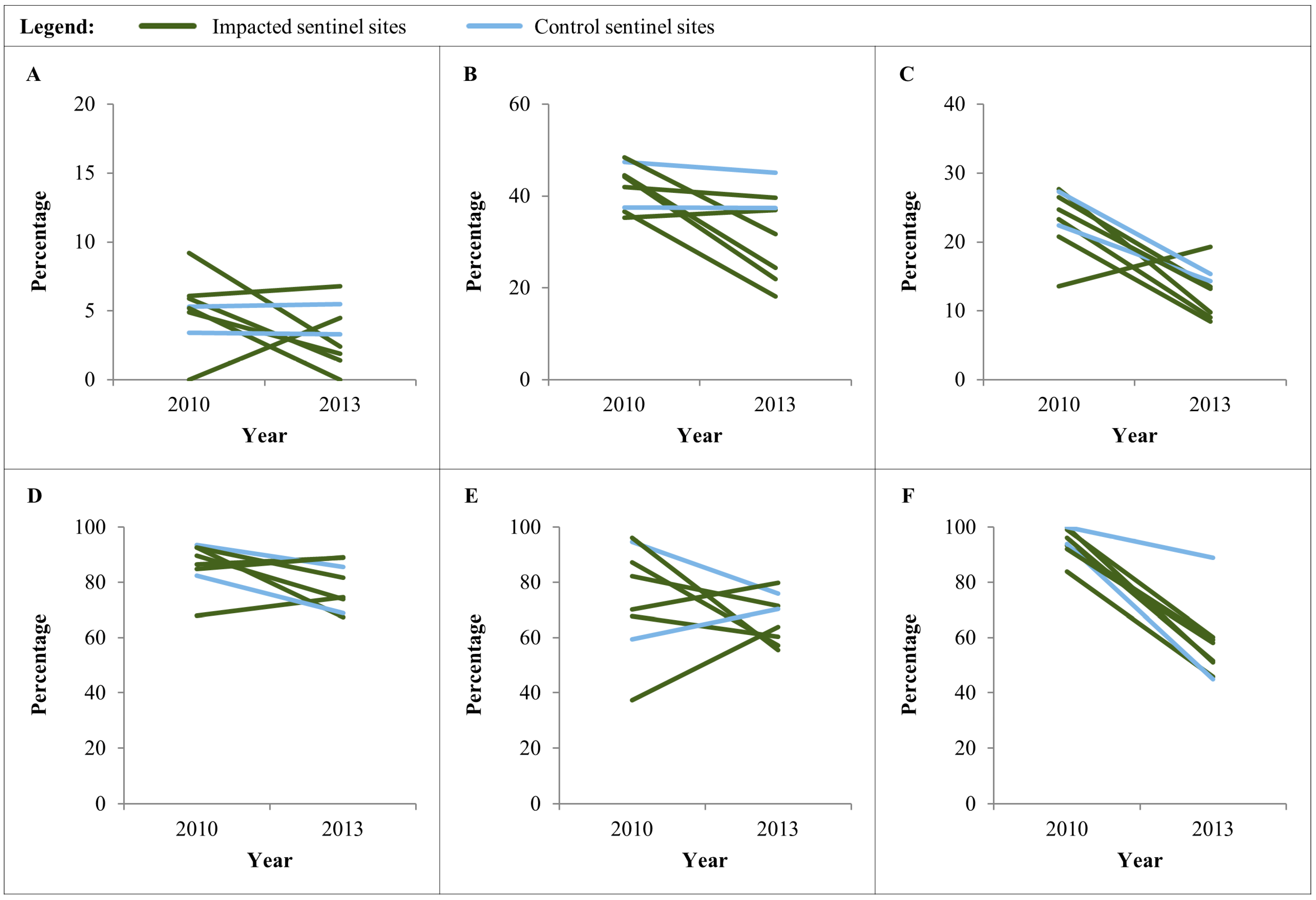

3.2. Anthropometric Indicators in Children Aged <59 Months

| Impacted Sentinel Sites | Control Sentinel Sites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2013 | 2010 | 2013 | ||

| Indicators in children aged <59 months | |||||

| Sample size (n) | Individuals | 421 | 390 | 164 | 214 |

| Households | 149 | 131 | 52 | 50 | |

| Sentinel sites | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| Mean/sentinel site (range) | 68 (24–99) | 58 (21–91) | 81 (75–86) | 100 (83–116) | |

| Wasting | Prevalence (95% CI) | 5.7 (3.4–8.0) | 2.8 (1.0–4.6) | 4.3 (0.9–7.7) | 4.2 (1.3–7.1) |

| Range | 0.0–9.2 | 0.0–6.8 | 3.4–5.3 | 3.3–5.5 | |

| p-value | 0.044 | 0.976 | |||

| Stunting | Prevalence (95% CI) | 41.8 (37.0–46.6) | 32.1 (27.3–36.8) | 42.1 (34.2–49.9) | 40.7 (33.8–47.5) |

| Range | 35.3–48.5 | 18.2–39.6 | 37.5–47.4 | 37.4–45.1 | |

| p-value | 0.004 | 0.781 | |||

| Underweight | Prevalence (95% CI) | 23.0 (18.9–27.2) | 13.3 (9.8–16.8) | 25.0 (18.1–31.9) | 15.0 (9.9–20.0) |

| Range | 13.6–27.7 | 8.5–19.3 | 22.4–27.3 | 14.3–15.4 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.014 | |||

| Indicators in children aged 6–59 months | |||||

| Sample size (n) | Individuals | 409 | 350 | 161 | 199 |

| Households | 149 | 131 | 52 | 50 | |

| Sentinel sites | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| Mean/sentinel site (range) | 68 (24–99) | 58 (21–91) | 81 (75–86) | 100 (83–116) | |

| P. falciparum | Prevalence (95% CI) | 73.8 (68.6–78.5) | 62.5 (56.4–68.2) | 76.0 (67.4–83.0) | 72.8 (66.5–78.3) |

| Range | 37.3–96.2 | 55.5–79.7 | 59.3–94.7 | 70.3–75.8 | |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.530 | |||

| Anemia | Prevalence (95% CI) | 85.8 (82.0–88.8) | 80.0 (75.3–84.0) | 87.5 (80.9–92.0) | 75.9 (69.5–81.3) |

| Range | 67.9–92.6 | 67.3–89.0 | 82.4–93.5 | 68.9–85.6 | |

| p-value | 0.033 | 0.005 | |||

| Use of insecticide treated nets | Prevalence (95% CI) | 94.6 (90.9–96.8) | 55.1 (47.0–63.0) | 96.8 (88.0–99.2) | 67.1 (53.9–78.1) |

| Range | 83.8–100.0 | 45.8–60.2 | 93.9–100.0 | 44.8–88.8 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Indicators in children aged 10–15 years | |||||

| Sample size (n) | Individuals | 180 | 181 | 60 | 60 |

| Sentinel sites | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| Mean/sentinel site (range) | 30 (30–30) | 30 (30–30) | 30 (30–30) | 30 (30–30) | |

| S. mansoni | Prevalence (95% CI) | 1.7 (0.0–3.6) | 3.9 (1.0–6.7) | 5.0 (0.0–10.7) | 8.3 (1.1–15.5) |

| Range | 0.0–3.3 | 0.0–13.3 | 3.3–6.7 | 6.7–10.0 | |

| p-value | 0.203 | 0.464 | |||

| A. lumbricoides | Prevalence (95% CI) | 1.1 (0.0–2.7) | 11.1 (6.4–15.6) | 1.7 (0.0–5.0) | 1.7 (0.0–5.0) |

| Range | 0.0–3.3 | 3.3–40.0 | 0.0–3.3 | 0.0–3.3 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | 1.000 | |||

| Hookworm | Prevalence (95% CI) | 23.9 (17.6–30.2) | 28.7 (22.1–35.4) | 40.0 (27.2–52.8) | 41.7 (28.8–54.5) |

| Range | 3.3–50.0 | 10.0–63.3 | 33.3–46.7 | 36.7–46.7 | |

| p-value | 0.296 | 0.853 | |||

| Indicators in children aged 6–59 months | |||||

| T. trichiura | Prevalence (95% CI) | 2.2 (0.1–4.4) | 1.1 (0.0–2.6) | 1.7 (0.0–5.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) |

| Range | 0.0–3.3 | 0.0–6.7 | 0.0–3.3 | 0.0–0.0 | |

| p-value | 0.406 | 0.315 | |||

| Indicators in women aged 15–49 years | |||||

| Sample size (n) | Individuals | 284 | 255 | 113 | 122 |

| Sentinel sites | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| Mean/sentinel site (range) | 47 (20–76) | 43 (21–58) | 57 (52–61) | 61 (58–64) | |

| Anemia | Prevalence (95% CI) | 72.8 (67.2–77.8) | 40.5 (34.4–46.8) | 75.9 (68.4–82.0) | 33.4 (25.5–42.5) |

| Range | 53.8–84.0 | 30.4–48.0 | 70.2–80.3 | 22.3–43.6 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

3.3. Anemia and P. falciparum Prevalence in Children Aged 6–59 Months

3.4. Anemia and Place of Delivery of the Last Born Child in Women Aged 15–49 Years

| Impacted Sentinel Sites | Control Sentinel Sites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2013 | 2010 | 2013 | ||

| Indicators in mothers/households participating in the questionnaire survey | |||||

| Sample size (n) | Individuals/households | 144 | 137 | 51 | 50 |

| Sentinel sites | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| Mean/sentinel site (range) | 24 (15–26) | 23 (17–27) | 25 (25–26) | 25 (25–25) | |

| % mothers giving birth at a health facility | Prevalence (95% CI) | 63.2 (54.8–71.1) | 81.0 (73.4–87.2) | 66.7 (52.1–79.2) | 68.0 (53.3–80.5) |

| Range | 26.9–91.7 | 47.1–100.0 | 34.6–100.0 | 48.0–88.0 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.886 | |||

| % households having access to safe sanitation | Prevalence (95% CI) | 19.4 (13.3–26.9) | 18.3 (12.2–25.7) | 39.2 (25.8–53.9) | 18.0 (8.6–31.4) |

| Range | 0.0–33.3 | 0.0–37.0 | 34.6–44.0 | 4.0–32.0 | |

| p-value | 0.798 | 0.019 | |||

3.5. Helminth Infection among School-Age Children and Household’s Access to Improved Sanitation

3.6. Presence/Absence of Coliform Bacteria in Drinking Water Samples

| Impacted Sentinel Sites | Control Sentinel Sites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2013 | 2010 | 2013 | ||

| Indicators for drinking water quality at household and source level | |||||

| Sample size (n) | Households | 72 | 60 | 24 | 20 |

| Sources | 18 | 16 | 6 | 9 | |

| Sentinel sites | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| % of household samples positive for coliform | Prevalence (95% CI) | 98.6 (92.5–99.9) | 100.0 (83.2–100.0) | 95.8 (78.9–99.9) | 100.0 (94.0–100.0) |

| Range | 91.7–100.0 | 100.0–100.0 | 91.7–100.0 | 100.0–100.0 | |

| p-value | 0.359 | 0.356 | |||

| % of source samples positive for coliform | Prevalence (95% CI) | 94.4 (72.7–99.9) | 87.5 (61.7–98.4) | 83.3 (35.9–99.6) | 88.9 (51.8–99.7) |

| Range | 50.0–100.0 | 66.7–100.0 | 75.0–100.0 | 75.0–100.0 | |

| p-value | 0.476 | 0.756 | |||

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Health Patterns

4.2. Implications for the Health Impact Assessment (HIA) Process

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rulli, M.C.; Saviori, A.; D’Odorico, P. Global land and water grabbing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.F.; D’Odorico, P.; Rulli, M.C. Land grabbing: A preliminary quantification of economic impacts on rural livelyhoods. Popul. Environ. 2014, 36, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Listorti, J.A. Bridging Environmental Health Gaps: Lessons for Sub-Saharan Africa Infrastructure Projects; The World Bank, Environmentally Sustainable Development Division: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Salcito, K.; Utzinger, J.; Weiss, M.G.; Münch, A.K.; Singer, B.H.; Krieger, G.R.; Wielga, M. Assessing human rights impacts in corporate development projects. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 42, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.S.; Krieger, G.R.; Divall, M.J.; Cissé, G.; Wielga, M.; Singer, B.H.; Tanner, M.; Utzinger, J. Untapped potential of health impact assessment. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Africa report. Sierra Leone: Green Pastures for Biofuels; The African Report: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, M.S.; Divall, M.J.; Krieger, G.R.; Balge, M.Z.; Singer, B.H.; Utzinger, J. Assessing health impacts in complex eco-epidemiological settings in the humid tropics: The centrality of scoping. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2011, 31, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dercon, S.; Gilligan, D.O.; Hoddinott, J.; Woldehanna, T. The impact of agricultural extension and roads on poverty and consumption growth in fifteen Ethiopian villages. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2009, 91, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschmidt, I.; Schwabe, C.; Benavente, L.; Torrez, M.; Ridl, F.C.; Segura, J.L.; Ehmer, P.; Nchama, G.N. Marked increase in child survival after four years of intensive malaria control. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 80, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, L.A.; Filoso, S. Expansion of sugarcane ethanol production in Brazil: Environmental and social challenges. Ecol. Appl. 2008, 18, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirado, M.C.; Cohen, M.J.; Aberman, N.; Meerman, J.; Thompson, B. Addressing the challenges of climate change and biofuel production for food and nutrition security. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1729–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.A.; Anderson, J.E.; Wallington, T.J. Impact of biofuel production and other supply and demand factors on food price increases in 2008. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anane, M.; Abiwu, C.Y. Independent Study Report of the Addax Bioenergy Sugercane-to-Ethanol Project in the Makeni Region in Sierra Leone; Sierra Leone Network on the Right to Food (Silnorf), Bread for All Switzerland: Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ActionAid UK. Broken Promises: The Impacts of Addax Bioenergy in Sierra Leone on Hunger and Livelihoods; ActionAid UK: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Action for Large-scale Land Acquisition Transparency (ALLAT). Who is Benefitting? The Social and Economic Impact of Three Large-Scale Land Investments in Sierra Leone: A Cost-Benefit Analysis; ALLAT: Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Addax Bioenergy. The Makeni Ethanol and Power Project. Available online: http://www.addaxbioenergy.com (accessed on June 2014).

- Bisset, R.; Driver, P. 2013 Annual Independent Public Environmental & Social Monitoring Report; Nippon Koei UK: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Introduction to Health Impact Assessment; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Good Practice Handbook: Cumulative Impact Assessment and Management: Guidance for the Private Sector in Emerging Markets; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Manley, G.; Lonsway, K.; Aron, R. Executive Summary of the Environmental, Social and Health Impact Assessment: Addax Bioenergy Project Sierra Leone; African Development Bank Group: Tunis, Tunisia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, M.S.; Knoblauch, A.M.; Righetti, A.A.; Divall, M.J.; Koroma, M.M.; Fofanah, I.; Turay, H.; Hodges, M.H.; Utzinger, J. Baseline health conditions in selected communities of Northern Sierra Leone as revealed by the health impact assessment of a biofuel project. Int. Health 2014, 6, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alliance for Malaria Prevention (AMP). Expanding the Ownership and Use of Mosquito Nets: Sierra Leone Country Profile; Alliance for Malaria Prevention: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Sierra Leone; Ministry of Health and Sanitation. Scaling up Maternal and Child Health through Free Health Care Services, One Year on. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/files/africacan/smaller-sierraleonehealthbulletin.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2014).

- HKI Sierra Leone. Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases: Sierra Leone: Annual Work Plan October 2012–September 2013; Helen Keller International: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koroma, A.S.; Chiwile, F.; Bangura, M.; Yankson, H.; Njoro, J. Capacity Development of the National Health System for CAM Scale up in Sierra Leone; Emergency Nutrition Network: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. Population Living in the Addax Bioenergy Sierra Leone Land Leasing Area as per December 2013; Addax Bioenergy: Mabilafu, Sierra Leone, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, M.S.; Divall, M.J.; Krieger, G.R.; Schmidlin, S.; Magassouba, M.L.; Knoblauch, A.M.; Singer, B.H.; Utzinger, J. Assessing health impacts in complex eco-epidemiological settings in the humid tropics: Modular baseline health surveys. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2012, 33, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogill, B. Anthropometric Indicators Measurement Guide; Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Test Performance: Results of WHO Product Testing of Malaria RDTs: Round 4 (2012); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- HemoCue. Operating Manual HemoCue Hb 201+. Available online: http://www.hemocue.com/index.php?page=3052 (accessed on June 2014).

- Katz, N.; Chaves, A.; Pellegrino, J. A simple device for quantitative stool thick-smear technique in schistosomiasis mansoni. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paolo 1972, 14, 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, M.H.; Koroma, M.; Baldé, M.S.; Turay, H.; Fofanah, I.; Bah, A.; Divall, M.J.; Winkler, M.S.; Zhang, Y.B. Current status of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in Beyla and Macenta prefecture, Forest Guinea. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 105, 672–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colitag. Presence/Absence Test Kit For Coliform Bacteria. Available online: http://www.colitag.com/ (accessed on June 2014).

- Delagua. OXFAM-Delagua Portable Water Testing Kit; University of Surrey: Guildford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNICEF/UNU. Iron Deficiency Anemia: Assessment, Prevention and Control: A Guide for Programme Managers; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sierra Leone; Measure DHS. Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey 2013: Preliminary Report; ICF International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Sanitation; ICF Macro. Sierra Leone Demographic and Health Survey 2008; Ministry of Health and Sanitation (Statistics Sierra Leone) and ICF Macro: Freetown and Calverton, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Anthro: Software for Assessing Growth and Development of the World’s Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, J. How did Sierra Leone provide free health care? Lancet 2011, 377, 1393–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxmen, A. Sierra Leone’s free health-care initiative: Work in progress. Lancet 2013, 381, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hillbruner, C.; Egan, R. Seasonality, household food security, and nutritional status in Dinajpur, Bangladesh. Food Nutr. Bull. 2008, 29, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martorell, R.; Young, M.F. Patterns of stunting and wasting: Potential explanatory factors. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, R.E.; Allen, L.H.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Caulfield, L.E.; de Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Mathers, C.; Rivera, J. Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 2008, 371, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, A.; Smith, S.J.; Yambasu, S.; Jambai, A.; Alemu, W.; Kabano, A.; Eisele, T.P. Household possession and use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets in Sierra Leone 6 months after a national mass-distribution campaign. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoblauch, A.M.; Winkler, M.S.; Archer, C.; Divall, M.J.; Owuor, M.; Yapo, R.M.; Yao, P.A.; Utzinger, J. The epidemiology of malaria and anaemia in the Bonikro mining area, central Côte d’Ivoire. Malar. J. 2014, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuasi, J.H.; Diap, G.; Nguah, S.B.; Karikari, P.; Boakye, I.; Jambai, A.; Lahai, W.K.; Louie, K.S.; Kiechel, J.R. Access to artemisinin-combination therapy (ACT) and other anti-malarials: National policy and markets in Sierra Leone. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keiser, J.; Castro, M.C.; Maltese, M.F.; Bos, R.; Tanner, M.; Singer, B.H.; Utzinger, J. Effect of irrigation and large dams on the burden of malaria on a global and regional scale. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005, 72, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Afrane, Y.A.; Zhou, G.; Lawson, B.W.; Githeko, A.K.; Yan, G. Effects of microclimatic changes caused by deforestation on the survivorship and reproductive fitness of Anopheles gambiae in western Kenya highlands. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006, 74, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Awolola, T.S.; Oduola, A.O.; Obansa, J.B.; Chukwurar, N.J.; Unyimadu, J.P. Anopheles gambiae s.s. breeding in polluted water bodies in urban Lagos, southwestern Nigeria. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2007, 44, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tusting, L.S.; Willey, B.; Lucas, H.; Thompson, J.; Kafy, H.T.; Smith, R.; Lindsay, S.W. Socioeconomic development as an intervention against malaria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2013, 382, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, A.R. Best practices for an insecticide-treated bed net distribution programme in sub-Saharan eastern Africa. Malar. J. 2011, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Sierra Leone; Ministry of Health and Sanitation. Implementation of Mass LLINs Distribution and Integrated Maternal and Child Health Week; Ministry of Health and Sanitation Sierra Leone: Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, M.H.; Soares Magalhães, R.J.; Paye, J.; Koroma, J.B.; Sonnie, M.; Clements, A.; Zhang, Y.B. Combined spatial prediction of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in Sierra Leone: A tool for integrated disease control. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, M.H.; Koroma, J.B.; Sonnie, M.; Kennedy, N.; Cotter, E.; MacArthur, C. Neglected tropical disease control in post-war Sierra Leone using the Onchocerciasis Control Programme as a platform. Int. Health 2011, 3, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strunz, E.C.; Addiss, D.G.; Stocks, M.E.; Ogden, S.; Utzinger, J.; Freeman, M.C. Water, sanitation, hygiene, and soil-transmitted helminth infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, P.; Yap, P.; Utzinger, J.; Du, Z.W.; Jiang, J.Y.; Chen, R.; Wu, F.W.; Chen, J.X.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, X.N. Control of soil-transmitted helminthiasis in Yunnan province, People’s Republic of China: Experiences and lessons from a 5-year multi-intervention trial. Acta Trop. 2015, 141, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Waterkeyn, J.; Cairncross, S. Creating demand for sanitation and hygiene through community health clubs: a cost-effective intervention in two districts in Zimbabwe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1958–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, B.; Sarisky, J.; Gelting, R.; Baffigo, V.; Seminario, R.; Centurion, C. A community demand-driven approach toward sustainable water and sanitation infrastructure development. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2011, 214, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M. Beyond the fence line: corporate social responsibility. Clin. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Projects and People: A Handbook for Addressing Project-Induced in-Migration; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Ebola Response Team. Ebola virus disease in West Africa—The first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1481–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Crawley, J. Reducing the burden of anemia in infants and young children in malaria-endemic countries of Africa: From evidence to action. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004, 71, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harris-Roxas, B.F.; Harris, P. Learning by doing: The value of case studies of health impact assessment. NSW Public Health Bull. 2007, 18, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemm, J. Health Impact Assessment: Past Achievement, Current Understanding, and Future Progress; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, M.S.; Divall, M.J.; Krieger, G.R.; Balge, M.Z.; Singer, B.H.; Utzinger, J. Assessing health impacts in complex eco-epidemiological settings in the humid tropics: Advancing tools and methods. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2010, 30, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopp, S.; Speich, B.; Hattendorf, J.; Rinaldi, L.; Mohammed, K.A.; Khamis, I.S.; Mohammed, A.S.; Albonico, M.; Rollinson, D.; Marti, H.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Kato-Katz and FLOTAC for assessing anthelmintic drug efficacy. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fewtrell, L.; Bartram, J. Water Quality; Guidelines, Standards and Health; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- WHO/ECHP. Health Impact Assessment: Main Concepts and Suggested Approach. Gothenburg Consensus Paper; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Danmark, 1999. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knoblauch, A.M.; Hodges, M.H.; Bah, M.S.; Kamara, H.I.; Kargbo, A.; Paye, J.; Turay, H.; Nyorkor, E.D.; Divall, M.J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Changing Patterns of Health in Communities Impacted by a Bioenergy Project in Northern Sierra Leone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 12997-13016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212997

Knoblauch AM, Hodges MH, Bah MS, Kamara HI, Kargbo A, Paye J, Turay H, Nyorkor ED, Divall MJ, Zhang Y, et al. Changing Patterns of Health in Communities Impacted by a Bioenergy Project in Northern Sierra Leone. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014; 11(12):12997-13016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212997

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnoblauch, Astrid M., Mary H. Hodges, Mohamed S. Bah, Habib I. Kamara, Anita Kargbo, Jusufu Paye, Hamid Turay, Emmanuel D. Nyorkor, Mark J. Divall, Yaobi Zhang, and et al. 2014. "Changing Patterns of Health in Communities Impacted by a Bioenergy Project in Northern Sierra Leone" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11, no. 12: 12997-13016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212997

APA StyleKnoblauch, A. M., Hodges, M. H., Bah, M. S., Kamara, H. I., Kargbo, A., Paye, J., Turay, H., Nyorkor, E. D., Divall, M. J., Zhang, Y., Utzinger, J., & Winkler, M. S. (2014). Changing Patterns of Health in Communities Impacted by a Bioenergy Project in Northern Sierra Leone. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(12), 12997-13016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212997