Abstract

Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) has emerged in the clinical field as a potential alternative to antibiotics to treat microbial infections. No cases of microbial viability recovery or any resistance mechanisms against it are yet known. 5,10,15-tris(1-Methylpyridinium-4-yl)-20-(pentafluorophenyl)-porphyrin triiodide (Tri-Py+-Me-PF) was used as photosensitizer. Vibrio fischeri and recombinant Escherichia coli were the studied bacteria. To determine the bacterial recovery after treatment, Tri-Py+-Me-PF (5.0 μM) was added to bacterial suspensions and the samples were irradiated with white light (40 W m−2) for 270 minutes. Then, the samples were protected from light, aliquots collected at different intervals and the bioluminescence measured. To assess the development of resistance after treatment, bacterial suspensions were exposed to white light (25 minutes), in presence of 5.0 μM of Tri-Py+-Me-PF (99.99% of inactivation) and plated. After the first irradiation period, surviving colonies were collected from the plate and resuspended in PBS. Then, an identical protocol was used and repeated ten times for each bacterium. The results suggest that aPDT using Tri-Py+-Me-PF represents a promising approach to efficiently destroy bacteria since after a single treatment these microorganisms do not recover their viability and after ten generations of partially photosensitized cells neither of the bacteria develop resistance to the photodynamic process.

1. Introduction

The use of antibiotics to destroy selectively microorganisms (MO) represents one of the most revolutionary progresses made in scientific medicine, resulting in the treatment and sometimes complete eradication of earlier incurable diseases [1,2]. It might have been supposed that at the beginning of the twenty first century, microbiologically-based diseases would have been reduced to a level that no longer had a serious impact on human health. However, bacteria have developed resistance mechanisms against antimicrobial drugs which were previously highly effective. Besides, bacteria replicate very rapidly and a mutation that helps a MO to survive in the presence of an antibiotic will quickly become predominant in the microbial population [1,3]. Due to resistance to all β-lactam antibiotics, the glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin has remained as last line of defense against Gram-positive bacteria. However, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci are species that are causing much concern at present [4] and there is an urgent need for the development of novel, convenient, non-resistant and inexpensive measures for fighting microbial diseases [1,5,6].

Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) represents a potential alternative methodology to inactivate microbial cells [7–9] and has already shown to be effective in vitro against bacteria, fungi, viruses and protozoa [5,10–17]. The aPDT approach is based on the photodynamic therapy concept that comprises the action of three components: a photosensitizing agent (PS), a light source of an appropriate wavelength (artificial light or sunlight) and oxygen [1,5,18–20]. Two oxidative mechanisms of photoinactivation (PI) are considered to be implicated in the inactivation of the target cells. The type I pathway involves electron/hydrogen atoms-transfer reactions from the PS triplet state with the participation of a substrate to produce radical ions while the type II pathway involves energy transfer from that triplet state to molecular oxygen to produce singlet oxygen (1O2) [3,5,21–23]. Both processes lead to highly toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as 1O2 and free radicals, able to irreversibly alter vital components of cells resulting in oxidative lethal damage [24,25]. The main advantages of aPDT are the non-target specificity, the few side effects, the prevention of the regrowth of the MO after treatment and the lack of development of resistance mechanisms due to the mode of action and type of biochemical targets (multi-target process) [9,20].

The photodynamic activity produces damages mainly in the cytoplasmatic membrane and in DNA [3]. The damages to the cytoplasmatic membrane can involve leakage of cellular contents or inactivation of membrane transport systems and enzymes [26,27]. Some damages produced in the DNA chain can be repaired by the action of DNA repairing systems [28]. However, it was shown that although DNA damage occurs it cannot be the main cause of bacterial cell photodynamic inactivation [3,29], since Deinococcus radiodurans, which is known to have a very efficient DNA repair mechanism, is easily killed by aPDT [30].

Although various studies have investigated the possible recovery of bacterial infections in animal models (in vivo) [31–33], there are no published results from studies that tested the possible viability recovery, in vitro, after aPDT treatment. Moreover, despite the fact various authors have stated that resistance to aPDT is unlikely to occur due to the non-specific killing mechanism (ROS cause damage on diverse bacterial structures) [34–41], only a few studies were conducted in order to determine if bacterial resistance occurs after several consecutive aPDT treatments. Cell wall structures and membranes are the main targets of photodynamic therapy drugs, and for this reason the drugs do not necessarily need to enter the cell. Specific and proper adhesion to these structures is usually considered sufficient for light-activated destruction of the target cell. Thus target cells have no chance to develop resistance by stopping uptake, increasing metabolic detoxification or increasing export of the drug [9].

The research concerning aPDT is more focused in the identification of new PS that kill rapidly and efficiently the MO and in the disclosure of their inactivation mechanisms. However, and regarding the emergence of bacterial resistance to antibiotics, it is important to control the PI process in terms of resistance development. Lauro et al. [42] investigated the selection of resistant bacterial strains in Peptostreptococcus micros and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans after repeated photosensitization of surviving cells with the porphycene-polylysine conjugates 2,7,12,17-tetrakis(2-methoxyethyl)-9-glutaramidoporphycene and 2,7,12,17-tetrakis(2-methoxyethyl)-9-p-carboxybenzyl-oxyporphycene. The results obtained by this group showed that the photosensitization of P. micros and A. actinomycetemcomitans by both PS induced no appreciable development of resistance in partially inactivated bacterial cells. The efficiency of photokilling underwent no change in ten subsequent irradiation sessions, even though cells which were damaged in a previous treatment were cultivated and re-exposed to porphycene and light [42]. Pedigo et al. [43] studied the possible development of bacterial resistance to aPDT after several treatments in antibiotic sensitive (MSSA) and resistant strains (MRSA) of S. aureus and antibiotic sensitive Escherichia coli. Bacteria were exposed to repetitive aPDT treatments using methylene blue as PS. The parameters were adjusted such that photoinactivation were lowest than 100% so that surviving colonies could be employed for subsequent exposures. No significant difference in E. coli cell death was observed through eleven repeated aPDT treatments. Similar results were observed using MSSA and MRSA, for which the killing rate did not significantly differ from over twenty five repeated exposures [43]. Jori et al. [44] determined that up to five consecutive generations of extensively photoinactivated MRSA (ca. 90%) show essentially identical degrees of sensitivity to phthalocyanine photosensitization. Although the known studies indicate that bacterial resistance to aPDT is unlikely, it is an important parameter to be evaluated when a new PS is considered for aPDT.

The bacterial bioluminescence method is considered to be a rapid, sensitive and cost-effective choice [12,45–47] to monitor the possible development of resistance after consecutive aPDT treatments, once that the photodynamic activity can be measured directly, continuously and in a nondestructively high-throughput screening or continuous-culture way [48]. A strong correlation between bioluminescence and viable counts was demonstrated in experimental systems [12,49,50], where the light output reflects the actual cells metabolic rate.

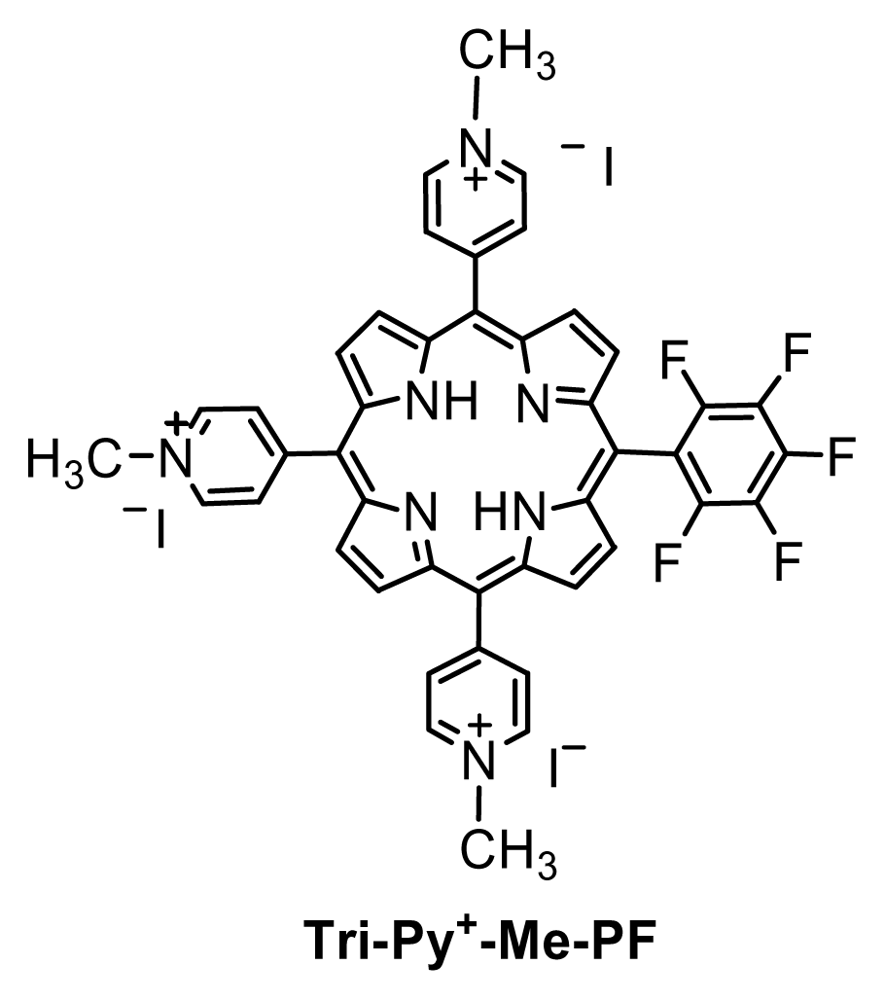

The aim of this study is to determine if in the presence of 5,10,15-tris(1-methylpyridinium-4-yl)-20-(pentafluorophenyl)porphyrin triiodide (Tri-Py+-Me-PF; Figure 1) the bacterial cells can recover their activity after photodynamic treatment and develop resistance to aPDT after repeated photodynamic treatments. The Tri-Py+-Me-PF is a tricationic porphyrin recently described by our group. We have shown that it is a promising PS for the inactivation of several types of MO [10–12,16,17,51].

Figure 1.

The structure of 5,10,15-tris(1-methylpyridinium-4-yl)-20-(pentafluorophenyl)-porphyrin triiodide.

To achieve the goals indicated above, the bacterial bioluminescent method was selected to monitor the bacterial activity of two bioluminescent Gram-negative bacteria: the non-transformed Vibrio fischeri and the recombinant Escherichia coli.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Results

The bacterial strains used in this work were a recombinant bioluminescent strain of E. coli described in a previous work [12] and the bioluminescent marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri ATCC 49387. Knowing that the light emission in these bacteria is directly proportional to their metabolic activity [12], we used their bioluminescence ability to evaluate their recovery after photodynamic treatment. The possible development of bacterial resistance after several aPDT treatments with Tri-Py+-Me-PF as PS was also evaluated using the bioluminescence method.

2.1.1. Bioluminescence versus CFU of an overnight culture

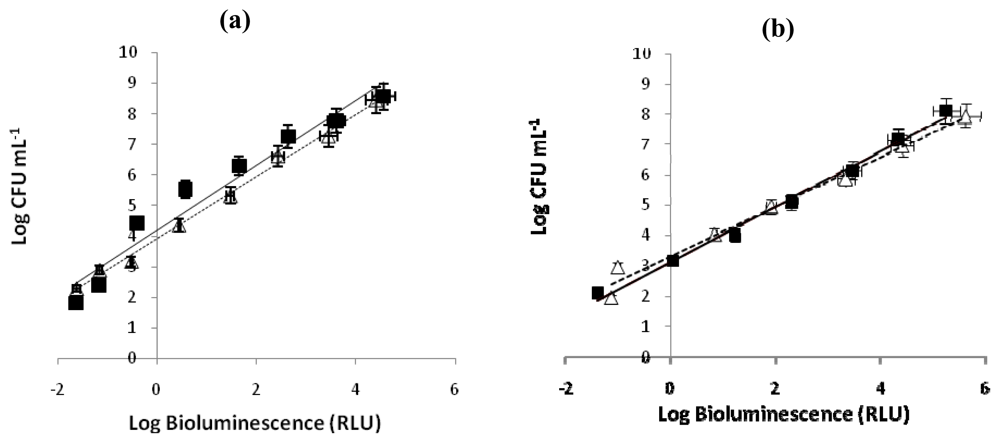

To evaluate the correlation between the colony-forming units (CFU) and the bioluminescence signal of V. fischeri and E. coli, the assays were carried out in dark conditions, with and without Tri-Py+-Me-PF porphyrin. A linear correlation between viable counts and the bioluminescence signal of overnight cultures of both bioluminescent strains was observed (Figure 2). These correlations are similar in the presence and in the absence of Tri-Py+-Me-PF and the bioluminescence results reflect the viable bacterial abundance.

Figure 2.

(a) Relationship between the bioluminescence signal and viable counts of overnight cultures of bioluminescent marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri (≈109 CFU mL−1) serially diluted in PBS with 3% of NaCl. (b) Relationship between the bioluminescence signal and viable counts of overnight cultures of recombinant bioluminescent Escherichia coli (≈108 CFU mL−1) serially diluted in PBS. Viable counts are expressed in CFU mL−1 and bioluminescence in relative light units (RLU). The values are expressed as the means of two independent experiments; error bars indicate the standard deviation. (--▵-- bacterial suspension in the absence of PS, —▪— bacterial suspension with 5.0 μM of Tri-Py+-Me-PF incubated 4h in the dark).

2.1.2. aPDT recovery study

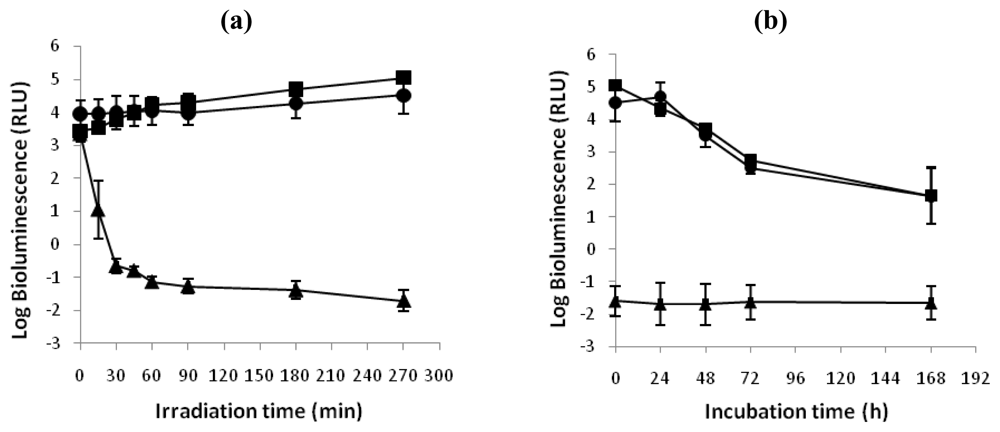

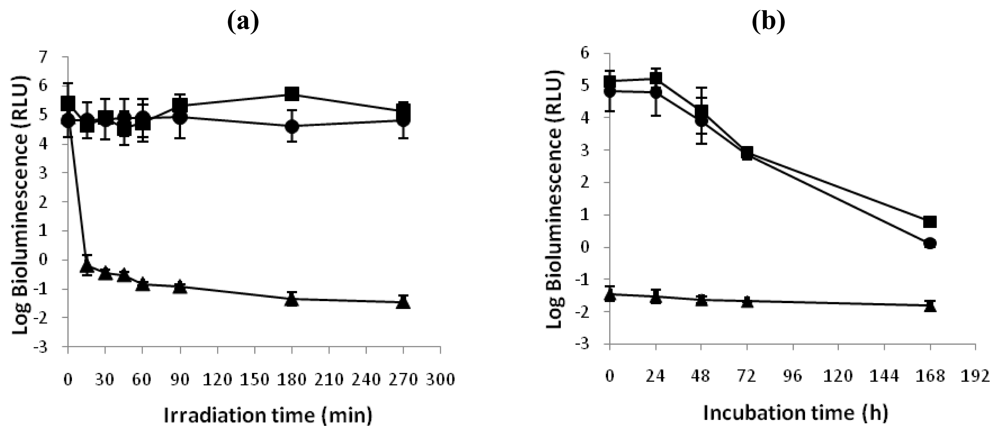

The ability of V. fischeri and E. coli cells to recover metabolic activity after a photodynamic treatment with 5.0 μM of Tri-Py+-Me-PF is represented in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. After 270 minutes of irradiation, the limits of detection for both bacteria were reached and a reduction of 5.1 log units on the bioluminescence signal of V. fischeri and 6.4 log units for bioluminescent E. coli was observed. Moreover, light and dark controls showed that the viability of these bacteria was neither affected by irradiation itself nor by the Tri-Py+-Me-PF in dark conditions (Figures 3A and 4A). This confirms that the reductions obtained on cell viability after irradiation of the treated samples are due to the photosensitizing effect of the porphyrin.

Figure 3.

(a) Bioluminescence monitoring of V. fischeri treated with Tri-Py+-Me-PF at 5.0 μM after 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 180 and 270 minutes of irradiation with white light (40 W m−2). (b) Bioluminescence signal of V. fischeri 24, 48, 72 and 168 hours after the photodynamic treatment. The values are expressed as the means of two independent experiments; error bars indicate the standard deviation. (-▪-dark control, -^- light control, -▴- Tri-Py+-Me-PF + light).

Figure 4.

(a). Bioluminescence monitoring of E. coli treated with Tri-Py+-Me-PF at 5.0 μM after 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 180 and 270 minutes of irradiation with white light (40 W m−2). (b) Bioluminescence signal of E. coli 24, 48, 72 and 168 hours after the photodynamic treatment. The values are expressed as the means of two independent experiments; error bars indicate the standard deviation. (-▪- dark control, -^- light control, -▴- Tri-Py+-Me-PF + light).

After one week of incubation in culture medium in dark conditions and in growth medium (Figures 3B and 4B), it was observed that the bioluminescence signal of photodynamic treated samples of V. fischeri and E. coli was unchanged during all period of incubation (log bioluminescence ≈−1.5 RLU for both V. fischeri and E. coli cells). No colonies were observed in the non-diluted (100) treated aliquot after plating in TSA medium with or without addition of NaCl, which is consistent with the bioluminescence results. It was also observed a decrease on the bioluminescence signal of light and dark controls of these bacteria.

2.1.3. aPDT resistance study

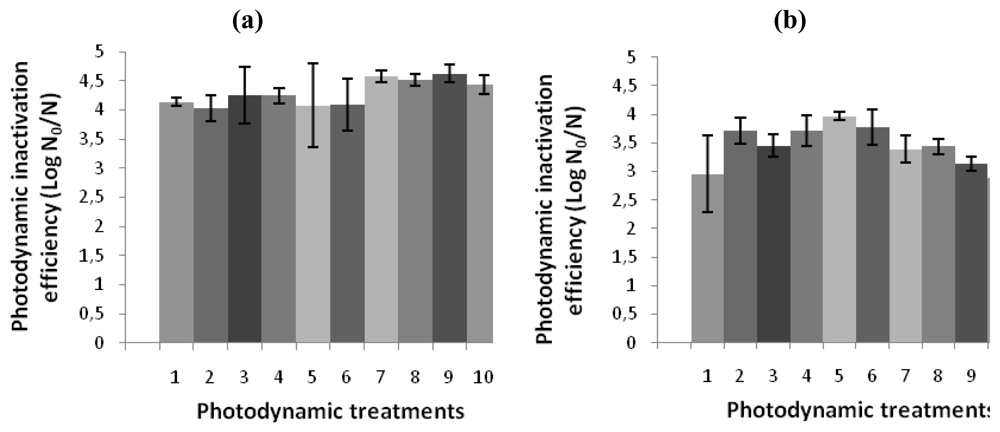

The effect of repeated treatments of bacterial suspensions of V. fischeri or E. coli with 5.0 μM of Tri-Py+-Me-PF to white light (40 W m−2) for 25 minutes are represented in Figure 5. The PI efficiency by Tri-Py+-Me-PF against both strains was not affected during the ten generations of photosensitized cells. After 25 min of irradiation at 40 W m−2 the Tri-Py+-Me-PF was able to destroy 99.99% of V. fischeri and E. coli cells.

Figure 5.

Photodynamic inactivation efficiency of ten consecutive generations of (a) V. fischeri and (b) E. coli by 5.0 μM of Tri-Py+-Me-PF after 25 min of irradiation with white light (40 W m−2), using the bacterial bioluminescence method. N0 and N represent, respectively, bioluminescence signal before and after the irradiation [42]. The values are expressed as the means of three independent experiments; error bars indicate the standard deviation.

2.2. Discussion

Microorganisms have adopted a variety of mechanisms to increase their resistance to antimicrobial drugs. These mechanisms comprise a thickening of their outer wall, encoding of new proteins which prevent the penetration of drugs, and onset of mutants deficient in porin channels allowing the influx of externally added chemicals [52–54]. The emergence of antibiotic resistance by pathogenic MO has led to the search of efficient alternative methods for which mechanisms of resistance must not occur [3,55]. The aPDT represents a potential approach to inactivate pathogenic MO [7,8] and has already shown to be efficient against bacteria, yeasts, viruses, and protozoa [5,10–16,18]. The main advantages of aPDT are the MO non-target specificity, the few side effects, the prevention of the regrowth of the MO after treatment and the potential lack of development of resistance mechanisms due to a multi-target process [9,20].

The results of this study shown that both bacteria when treated with the tricationic porphyrin Tri-Py+-Me-PF and irradiated with white light (40 W m−2) for 270 minutes are unable to recover metabolic activity. When samples were maintained for one week in dark conditions and under medium growth, after the photodynamic treatments, the bioluminescence signal remains the same for both V. fischeri and E. coli cells during all period of incubation (≈−1.5 log RLU). The bioluminescence signal reduction observed in dark and light controls can be due to the lack of nutrients and/or the accumulation of toxic products from bacteria metabolism. It was also clear that the results obtained in this study corroborate the literature [42–44] relative to the absence of resistance mechanisms after the photodynamic process. In fact, no significant reduction in the efficiency of photosensitization of V. fischeri and E. coli was observed after ten consecutive photosensitization sessions of 25 minutes with 5.0 μM of Tri-Py+-Me-PF. If bacterial resistance would occur, important reductions on the bacterial photoinactivation efficiency would be detected between experiments (and the irradiation time required to reach 99.99% of photosensitized cells should increase). Various authors affirmed that cultures on stationary phase show a certain degree of resistance to the PS [34,56]. However, others refer that bacteria susceptibility to PS is independent from the growth phase [57,58]. In this study, the cultures were used at the same growth phase for all assays (stationary growth phase). As the bacterial colonies have been aseptically removed from the plate and resuspended in PBS, the cellular density obtained after the colony resuspension could be different. To avoid differences in the PI efficiency due to different bacterial densities, this parameter was controlled in all the experiments by measuring the optical density of the bacteria suspension before each assay.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Photosensitizer

The tricationic porphyrin used in this work [5,10,15-tris(1-methylpyridinium-4-yl)-20-(penta-fluorophenyl)porphyrin triiodide, Tri-Py+-Me-PF] was prepared in two steps according to the literature [59]. A 500 μM stock solution of Tri-Py+-Me-PF porphyrin in DMSO was prepared and maintained at 4 °C.

3.2. Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The bacterial strains used in this work were a recombinant bioluminescent strain of E. coli prepared in a previous work [12] and the bioluminescent marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri ATCC 49387. Both E. coli and V. fischeri were stored at −80 °C in 10% glycerol. Before each assay, an aliquot of V. fischeri was aseptically plated on tryptic soy agar (TSA, Merck) complemented with 3% of NaCl (because of the osmotic pressure required to natural light emission to occur) and grown for one day at 25 °C. Next, one colony was aseptically inoculated on 30 mL Luria-Bertani broth with saline medium (LBS; 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract and 30 g NaCl per liter; pH 7.5) [60] and grown for one day at 25 °C under stirring (100 rpm). An aliquot of this culture (240 μL) was subcultured in 30 mL of LBS and grown overnight at 25 °C under stirring (100 rpm). The same procedure was carried out with an E. coli strain containing two plasmids that confer resistance to two antibiotics: ampicilin (Amp) and chloramphenicol (Cm). For that reason, E. coli was aseptically plated on TSA with 100 mg mL−1 of Amp and 25 mg mL−1 of Cm and grown for one day at 25 °C. Next, one colony was aseptically inoculated on tryptic soy broth (TSB, Merck) with both antibiotics and grown for one day at 25 °C under stirring (100 rpm). Then, an aliquot of this culture was subcultured in 30 mL of TSB with Amp and Cm and grown overnight at 25 °C under stirring (100 rpm).

3.3. Irradiation conditions

The studies were carried out by exposing the samples to white light (PAR radiation, 13 lamps OSRAM 21 of 18 W each one, 380–700 nm) with a fluence rate of 40 W m−2 (measured with a radiometer LI-COR Model LI-250). As V. fischeri emits light at temperatures below 30 °C [61], the samples were placed on a tray with water in order to maintain the samples at a constant temperature (25–28 °C).

3.4. Bioluminescence versus CFU

To evaluate the correlation between the CFU and the bioluminescence signal of V. fischeri, two assays were carried out in dark conditions, with and without Tri-Py+-Me-PF porphyrin. Two suspensions were prepared from an overnight culture of V. fischeri, diluting the culture (1:10) in fresh phosphate buffered saline with 3% of NaCl (PBS with 3% of NaCl: 30 g NaCl, 0.2 g KCl, 1.44 g Na2HPO4 and 0.24 g KH2PO4 per liter; pH 7.4) to a final concentration of 107 CFU mL−1. In one of these bacterial suspensions, an appropriate volume of porphyrin was added to achieve a final concentration of 5.0 μM, followed by a dark incubation for 4 h at 25–28 °C under stirring. Next, both suspensions were serially diluted (10−1–10−7) in PBS with 3% of NaCl. The non-diluted (100) and the diluted aliquots were plated in TSA with 3% of NaCl (100 μL) and, simultaneously, were read on a luminometer (500 μL) (TD-20/20 Luminometer, Turner Designs, Inc., USA) to determine the bioluminescence signal. The correlation between the CFU and the bioluminescence signal of E. coli was evaluated following the procedure described above for V. fischeri. However, the cultures and suspensions were diluted in PBS (PBS; 8 g NaCl, 0.2 g KCl, 1.44 g Na2HPO4 and 0.24 g KH2PO4 per liter; pH 7.4) and pour plated in TSA without NaCl. Both experiments were done in duplicate and the results were averaged.

3.5. aPDT recovery study

A photodynamic inactivation assay was conducted in order to determine if bacterial cells can recover their metabolism after an effective treatment. For this purpose, cultures of V. fischeri and E. coli were grown overnight and diluted tenfold in PBS (supplemented with 3% NaCl in the case of V. fischeri) to a final concentration of 107 CFU mL−1. These bacterial suspensions were equally distributed in 600 mL sterilized and acid-washed beakers. Afterwards, the appropriate volume of Tri-Py+-Me-PF solution was added to achieve a final concentration of 5.0 μM (total volume in the beakers was 15 mL). The samples were protected from light with aluminum foil and incubated for 10 min at 25–28 °C, under stirring (100 rpm), to promote the porphyrin binding to bacterial cells. Then, the mixtures were exposed to white light with a fluence rate of 40 W m−2 for 270 minutes (corresponding to a light fluence of 64.8 J cm−2) under 100 rpm (25–28 °C). Aliquots of treated and control samples were collected at time 0 and after 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 180 and 270 min of light exposure and the bioluminescence signal was measured in the luminometer. After 270 min of irradiation, when all bacteria were inactivated to the detection limit of the method, the samples were protected from light with aluminum foil and maintained under stirring at 25–28 °C. Aliquots of samples irradiated for 270 min and control samples were collected after 24, 48, 72 and 168 hours post-irradiation and the bioluminescence signal was measured in the luminometer. Light and dark controls were included in all experiments. In the light control no Tri-Py+-Me-PF was added, but the beaker was exposed to the same irradiation protocol. In the dark control, the Tri-Py+-Me-PF was added to achieve a final concentration of 5.0 μM and it was covered with aluminum foil. Both experiments were done in duplicate and the results were averaged.

3.6. aPDT resistance study

In order to assess the possible development of resistance in bacterial cells after photosensitized inactivation, cultures of V. fischeri and E. coli grown overnight were centrifugated at 10,000 g for 15 minutes to remove dead cells and residues of culture medium, and the cells thus obtained were resuspended in PBS (supplemented with 3% of NaCl in the case of V. fischeri). Bacterial suspensions (107 CFU mL−1) were equally distributed in 600 mL sterilized and acid-washed beakers and the suitable volume of Tri-Py+-Me-PF solution was added to achieve a final concentration of 5.0 μM (total volume was 10 mL per beaker). The samples were protected from the light with aluminum foil and incubated for 10 min at 25 °C, under stirring (100 rpm), to promote the porphyrin binding to bacterial cells. Afterwards, the mixtures were exposed to white light with a fluence rate of 40 W m−2 (under stirring at 25–28 °C) for 25 minutes. In that way, ca. 1 log unit of surviving bacteria is achieved. At the end of each treatment, an aliquot of both samples was plated on TSA and the plates were incubated for 48 hours at 25 °C in the case of V. fischeri and overnight at 25 °C for E. coli. Three surviving colonies from a plate of each bacterium were collected and each one was centrifugated at 10,000 g (15 minutes), resuspended in PBS and inoculated on the suitable liquid medium. Subsequently, the bacterial suspensions were incubated in the dark with the PS and exposed to visible light using an identical irradiation protocol that was repeated for ten times for each bacterium. Before each assay, the optical densities (O.D.) of cultures of V. fischeri and E. coli were controlled and monitored to O.D. of 0.5 and 1.3 (660 nm), approximately. The PI efficiency was expressed as log N0/N, where N0 and N represent the bioluminescence signal before and after the irradiation, respectively [42].

4. Conclusions

This study shows that the promising photosensitizer Tri-Py+-Me-PF is able to destroy efficiently Gram-negative bacteria, after the photodynamic treatment, without the recovery of bacterial viability. It was also confirmed that the bacteria photosensitized by this photosensitizer do not develop resistance mechanisms against the photodynamic process.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Fernando Gonçalves (University of Aveiro, Portugal) for kindly providing the V. fischeri strain and to Paula Gonçalves (University of Aveiro, Portugal) for the access to the luminometer. Thanks are also due to the University of Aveiro, Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) and FEDER for funding the Organic Chemistry Research Unit (QOPNA). To CESAM (Centro de Estudos do Ambiente e do Mar) for funding the Microbiology Reserch Group. Eliana Alves (SFRH/BD/41806/2007) and Carla M.B. Carvalho (SFRH/BD/38611/2007) are also grateful to FCT for their PhD grants.

- Samples Availability: Available from the authors.

References

- Jori, G; Brown, SB. Photosensitized inactivation of microorganisms. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2004, 3, 403–405. [Google Scholar]

- Tunger, O; Dinc, G; Ozbakkaloglu, B; Atman, C; Algun, U. Evaluation of rational antibiotic use. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2000, 15, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin, MR; Hasan, T. Photodynamic therapy: A new antimicrobial approach to infectious disease? Photochem Photobiol Sci 2004, 3, 436–450. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, BA. Antibiotic resistance. Control strategies. Crit Care Clin 1998, 14, 309–327. [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright, M. Photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy (PACT): A review. J Antimicrob Chemother 1998, 42, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, Z; Hanania, J; Nitzan, Y. Bactericidal effects of photoactivated porphyrins–an alternative approach to antimicrobial drugs. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 1990, 5, 281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Caminos, DA; Spesia, MB; Pons, P; Durantini, EN. Mechanisms of Escherichia coli photodynamic inactivation by an amphiphilic tricationic porphyrin and 5,10,15,20-tetra(4-N,N,N-trimethylammoniumphenyl) porphyrin. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2008, 7, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, PW; Stapleton, PD; Luzio, JP. New ways to treat bacterial infections. Drug Discovery Today 2002, 7, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Winckler, KD. Special section: Focus on anti-microbial photodynamic therapy (PDT). J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 2007, 86, 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, L; Alves, E; Carvalho, CMB; Tomé, JPC; Faustino, MAF; Neves, MGPMS; Tomé, AC; Cavaleiro, JAS; Cunha, Â; Almeida, A. Sewage bacteriophage photoinactivation by cationic porphyrins: A study of charge effect. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2008, 7, 415–422. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, E; Costa, L; Carvalho, C; Tome, J; Faustino, M; Neves, M; Tome, A; Cavaleiro, J; Cunha, A; Almeida, A. Charge effect on the photoinactivation of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria by cationic meso-substituted porphyrins. BMC Microbiol 2009, 9, 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, E; Carvalho, CMB; Tomé, JPC; Faustino, MAF; Neves, M; Tomé, AC; Cavaleiro, JAS; Cunha, A; Mendo, S; Adelaide, A. Photodynamic inactivation of recombinant bioluminescent Escherichia coli by cationic porphyrins under artificial and solar irradiation. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2008, 35, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright, W. Photoantimicrobials-a PACT against resistance and infection. Drugs Fut 2004, 29, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jemli, M; Alouini, Z; Sabbahi, S; Gueddari, M. Destruction of fecal bacteria in wastewater by three photosensitizers. J Environ Monit 2002, 4, 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- Merchat, M; Bertoloni, G; Giacomini, P; Villanueva, A; Jori, G. Meso-substituted cationic porphyrins as efficient photosensitizers of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 1996, 32, 153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A; Almeida, A; Carvalho, CMB; Tomé, JPC; Faustino, MAF; Neves, MGPMS; Tomé, AC; Cavaleiro, JAS; Cunha, Â. Porphyrin derivatives as photosensitizers for the inactivation of Bacillus cereus endospores. J Appl Microbiol 2009, 106, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, CMB; Tomé, JPC; Faustino, MAF; Neves, MGPMS; Tomé, AC; Cavaleiro, JAS; Costa, L; Alves, E; Oliveira, A; Cunha, Â; Almeida, A. Antimicrobial photodynamic activity of porphyrin derivatives: Potential application on medical and water disinfection. J Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 2009, 13, 574–577. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnett, R. Chemical aspects of photodynamic therapy. In Advanced Chemistry Texts; Gordon and Breach Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 1, p. 324. [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright, M. Methylene blue derivatives-suitable photoantimicrobials for blood product disinfection? Int J Antimicrob Agents 2000, 16, 381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Jori, G; Fabris, C; Soncin, M; Ferro, S; Coppellotti, O; Dei, D; Fantetti, L; Chiti, G; Roncucci, G. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of microbial infections: Basic principles and perspective applications. Lasers Surg Med 2006, 38, 468–481. [Google Scholar]

- Calin, MA; Parasca, SV. Light sources for photodynamic inactivation of bacteria. Lasers Med Sci 2009, 24, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, FS; Bentley, MVLB. Photodynamic therapy of skin cancers: Sensitizers, clinical studies and future directives. Pharm Res 2000, 17, 1447–1455. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, RF; McCarron, PA; Tunney, MM. Antifungal photodynamic therapy: A review. Microbiol Res 2008, 163, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, M; Crutchley, R. Photosensitized singlet oxygen and its applications. Coord Chem Rev 2002, 233, 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Ergaieg, K; Chevanne, M; Cillard, J; Seux, R. Involvement of both type I and type II mechanisms in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria photosensitization by a meso-substituted cationic porphyrin. Sol Energy 2008, 82, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Mettath, S; Munson, BR; Pandey, RK. DNA interaction and photocleavage properties of porphyrins containing cationic substituents at the peripheral position. Bioconjug Chem 1999, 10, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H; Fedorova, OS; Grachev, AN; Trumble, WR; Bohach, GA; Czuchajowski, L. A series of meso-tris(N-methyl-pyridiniumyl)-(4-alkylamidophenyl) porphyrins: Synthesis, interaction with DNA and antibacterial activity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1997, 1354, 252–260. [Google Scholar]

- Imray, FP; MacPhee, DG. The role of DNA polymerase I and the rec system in survival of bacteria and bacteriophages damaged by the photodynamic action of acridine orange. Mol Gen Genet 1973, 123, 289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Durantini, EN. Photodynamic inactivation of bacteria. Curr Bioact Comp 2006, 2, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, M; Schmitz, C; Horneck, G. High sensitivity of Deinococcus radiodurans to photodynamically-produced singlet oxygen. Int J Radiat Biol 1998, 74, 249–253. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts, SAG; Demidova, TN; Aalders, MCG; Hasan, T; Hamblin, MR. Photodynamic therapy for Staphylococcus aureus infected burn wounds in mice. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2005, 4, 503–509. [Google Scholar]

- Gad, F; Zahra, T; Francis, KP; Hasan, T; Hamblin, MR. Targeted photodynamic therapy of established soft-tissue infections in mice. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2004, 3, 451–458. [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein, A; Klein, D; Kopolovic, J; Winkler, E; Malik, Z; Keller, N; Nitzan, Y. The use of porphyrins for eradication of Staphylococcus aureus in burn wound infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 1997, 19, 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, M; MacRobert, A; Meghji, S; Henderson, B; Wilson, M. A study of the uptake of toluidine blue O by Porphyromonas gingivalis and the mechanism of lethal photosensitisation. Photochem Photobiol 1998, 68, 370–376. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, GS; Wilson, M; Nair, SP. Lethal photosensitization of wound-associated microbes using indocyanine green and near-infrared light. BMC Microbiol 2008, 8, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi, B; Sreeradha, B. Role of dye molecules remaining outside the cell during photodynamic inactivation of Escherichia coli in the presence of acriflavine. Photochem Photobiol 1989, 29, 403–405. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg, B; Gross, E; Nitzan, Y; Malik, Z. Electric depolarization of photosensitized cells: Lipids vs. protein alterations. Biochim Biophys Acta 1993, 1151, 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, T; Kobayashi, K. In vivo evidence for the photodynamic membrane damage as a determining step of the inactivation of yeast cells sensitized by toluidine blue. Photochem Photobiol 1977, 25, 399–401. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, CM; Tunney, MM; McCarron, PA; Donnelly, RF. Drug delivery strategies for photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy: From benchtop to clinical practice—A review. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 2009, 95, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Carré, V; Gaud, O; Sylvain, I; Bourdon, O; Spiro, M; Biais, J; Granet, R; Krausz, P; Guilloton, M. Fungicidal properties of meso-arylglycosylporphyrins: Influence of sugar substituents on photoinduced damage in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 1999, 48, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Maisch, T; Szeimies, RM; Jori, G; Abels, C. Antibacterial photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2004, 3, 907–917. [Google Scholar]

- Lauro, FM; Pretto, P; Covolo, L; Jori, G; Bertoloni, G. Photoinactivation of bacterial strains involved in periodontal diseases sensitized by porphycene-polylysine conjugates. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2002, 1, 468–470. [Google Scholar]

- Pedigo, LA; Gibbs, AJ; Scott, RJ; Street, CN. Absence of bacterial resistance following repeat exposure to photodynamic therapy. Proc SPIE 2009, 7380, 73803H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jori, G; Coppellotti, O. Inactivation of pathogenic microorganisms by photodynamic techniques: Mechanistic aspects and perspective applications. Anti-Infect Agents Med Chem 2007, 6, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin, MR; O’Donnell, DA; Murthy, N; Contag, CH; Hasan, T. Rapid control of wound infections by targeted photodynamic therapy monitored by in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Photochem Photobiol 2002, 75, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, KP; Yu, J; Bellinger-Kawahara, C; Joh, D; Hawkinson, MJ; Xiao, G; Purchio, TF; Caparon, MG; Lipsitch, M; Contag, PR. Visualizing pneumococcal infections in the lungs of live mice using bioluminescent Streptococcus pneumoniae transformed with a novel gram-positive lux transposon. Infect Immun 2001, 69, 3350–3358. [Google Scholar]

- Vesterlund, S; Paltta, J; Laukova, A; Karp, M; Ouwehand, AC. Rapid screening method for the detection of antimicrobial substances. J Microbiol Methods 2004, 57, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, SJ; Salisbury, V; Lewis, RJ; Sharpe, JA; MacGowan, AP. Expression of lux genes in a clinical isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Using bioluminescence to monitor gemifloxacin activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002, 46, 538–542. [Google Scholar]

- Marincs, F. On-line monitoring of growth of Escherichia coli in batch cultures by bioluminescence. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2000, 53, 536–541. [Google Scholar]

- Rocchetta, HL; Boylan, CJ; Foley, JW; Iversen, PW; LeTourneau, DL; McMillian, CL; Contag, PR; Jenkins, DE; Parr, TRJ. Validation of a noninvasive, real-time imaging technology using bioluminescent Escherichia coli in the neutropenic mouse thigh model of infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001, 45, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, CMB; Gomes, A; Fernandes, SCD; Prata, ACB; Almeida, MA; Cunha, MA; Tome, JPC; Faustino, MAF; Neves, M; Tome, AC. Photoinactivation of bacteria in wastewater by porphyrins: Bacterial beta-galactosidase activity and leucine-uptake as methods to monitor the process. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 2007, 88, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle-Vavra, S; Labischinski, H; Ebert, CC; Ehlert, K; Daum, RS. A spectrum of changes occurs in peptidoglycan composition of glycopeptide-intermediate clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001, 45, 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Roland, KL; Esther, CR; Spitznagel, JK. Isolation and characterization of a gene, pmrD, from Salmonella typhimurium that confers resistance to polymixin when expressed in multiple copies. J Bacteriol 1994, 176, 3589–3597. [Google Scholar]

- Harder, KJ; Nikaido, H; Matsuhashi, M. Mutants of Escherichia coli that are resistant to certain beta-lactam compounds lack the ompF porin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1981, 20, 549–552. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, GH; Mekalanos, J. Development of antimicrobial agents in the era of new and reemerging infectious diseases and increasing antibiotic resistance. J Am Med Assoc 2001, 285, 601–605. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzan, Y; Shainberg, B; Malik, Z. The mechanism of photodynamic inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus by deuteroporphyrin. Curr Microbiol 1989, 19, 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Banfi, S; Caruso, E; Buccafurni, L; Battini, V; Zazzaron, S; Barbieri, P; Orlandi, V. Antibacterial activity of tetraaryl-porphyrin photosensitizers: An in vitro study on Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 2006, 85, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gad, F; Zahra, T; Hasan, T; Hamblin, MR. Effects of growth phase and extracellular slime on photodynamic inactivation of gram-positive pathogenic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004, 48, 2173–2178. [Google Scholar]

- Tomé, JPC; Neves, MGPMS; Tomé, AC; Cavaleiro, JAS; Soncin, M; Magaraggia, M; Ferro, S; Jori, G. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of new poly-S-lysine-porphyrin conjugates. J Med Chem 2004, 47, 6649–6652. [Google Scholar]

- Geske, GD; O’Neill, JC; Blackwell, HE. N-phenylacetanoyl-L-homoserine lactones can strongly antagonize or superagonize quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri. ACS Chem Biol 2007, 2, 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Scheerer, S; Gomez, F; Lloyd, D. Bioluminescence of Vibrio fischeri in continuous culture: Optimal conditions for stability and intensity of photoemission. J Microbiol Methods 2006, 67, 321–329. [Google Scholar]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).