Abstract

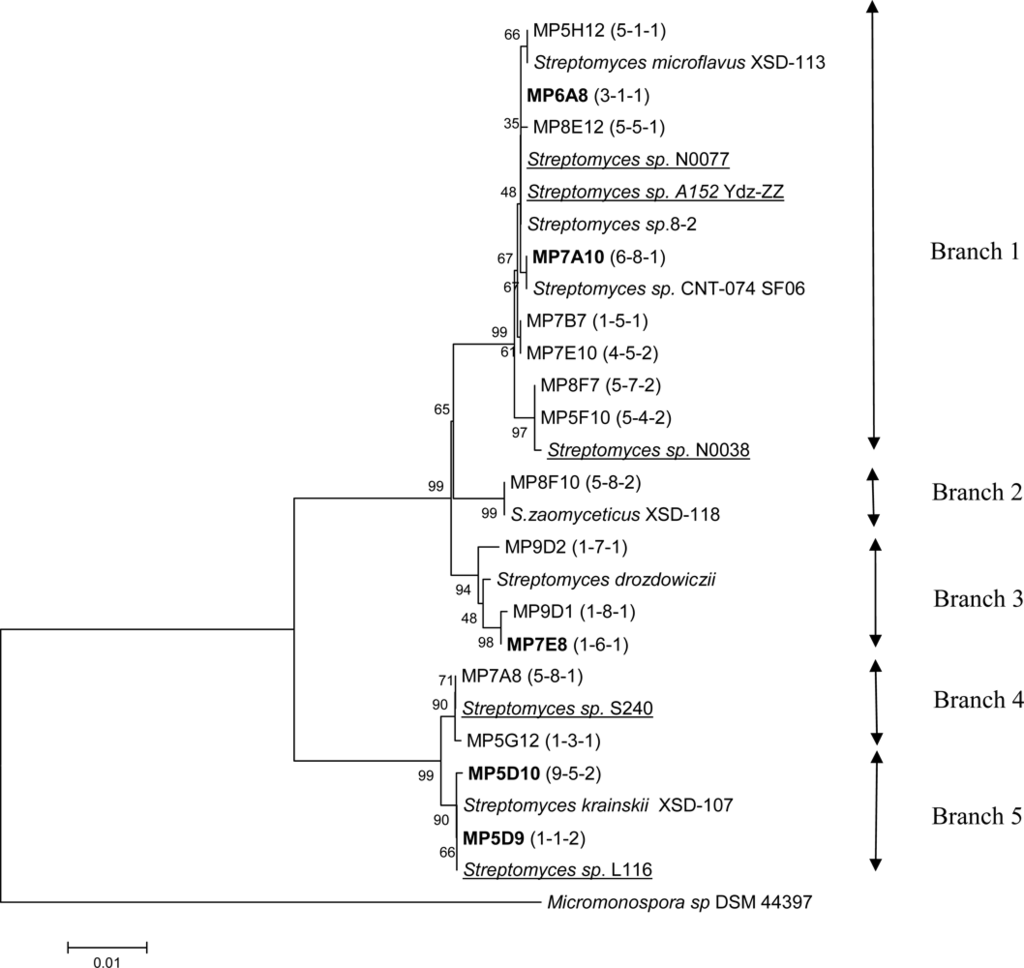

The water surface microlayer is still poorly explored, although it has been shown to contain a high density of metabolically active bacteria, often called bacterioneuston. Actinomycetes from the surface microlayer in the Trondheim fjord, Norway, have been isolated and characterized. A total of 217 isolates from two separate samples morphologically resembling the genus Streptomyces have been further investigated in this study. Antimicrobial assays showed that about 80% of the isolates exhibited antagonistic activity against non-filamentous fungus, Gram-negative, and Gram-positive bacteria. Based on the macroscopic analyses and inhibition patterns from the antimicrobial assays, the sub-grouping of isolates was performed. Partial 16S rDNAs from the candidates from each subgroup were sequenced and phylogenetic analysis performed. 7 isolates with identical 16S rDNA sequences were further studied for the presence of PKS type I genes. Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of the PKS gene fragments revealed that horizontal gene transfer between closely related species might have taken place. Identification of unique PKS genes in these isolates implies that de-replication can not be performed based solely on the 16S rDNA sequences. The results obtained in this study suggest that streptomycetes from the neuston population may be an interesting source for discovery of new antimicrobial agents.

1. Introduction

Search for new biologically active microbial secondary metabolites is important in order to meet the increasing demand for new antibiotics. Actinomycetes, especially those belonging to the genus Streptomyces, are known to produce a wide variety of biologically active compounds. Streptomyces bacteria were reported to produce ~70% of the currently characterized actinomycete natural products [1]. However, most of the Streptomyces characterized up to date were isolated from the terrestrial environment, while those originating from marine sources still remain poorly explored.

In an environment with high densities of metabolically active bacteria, competition is likely to be fierce, and properties such as production of antibiotics may give organisms an advantage. A number of antibiotic producers have been isolated from the marine environments [2, 3], and experimental data indicate that production of antibiotics could play an important role in the competitive relationship within the marine bacterial populations [4]. Antagonistic interactions among soil-living microorganisms are well documented, and are attributed to the production of antibiotics by certain bacteria and fungi in environments rich in organic material [5, 6]. Recently, the same trend has been discovered for marine microorganisms, which are abundant in mesotrophic and eutrophic waters or during phytoplankton blooms [7].

In a study of antagonistic interactions among marine pelagic bacteria it was found that more than half of the isolates expressed antagonistic activity, and this trait was more common among particle-associated (66%) than free-living bacteria (40%) [8]. Particles often tend to accumulate at the sea surface, and the aquatic surface layer contains a series of sub layers [9]. Neuston is a collective name for the life forms in the surface layer of oceans and lakes, and can be divided into epineuston and hyponeuston. Epineuston organisms live on the top of the water surface, and are naturally dependent on the surface tension of the water. Hyponeuston organisms live in the top few centimetres of the water column. High densities of metabolically active bacteria, often called bacterioneuston, are found in the surface microlayer [10-13].

Norwegian marine ecosystems have developed in a rather cold and severe climate, suggesting that the selective pressure on microorganisms comprising parts of such systems must have been quite unique (cold seawater environment). Because of this, it seems likely that these microorganisms have developed antibiotic biosynthesis pathways that differ from those utilized by terrestrial microorganisms. Even though the diversity of microorganisms in the marine environment is high, only a minor fraction (less than 1 %) can be cultivated in the laboratory, presumably because of failure to mimic the natural growth conditions [14]. In this work we isolated Streptomyces bacteria from the surface microlayer in the Trondheim fjord (Norway). The isolates were characterized using molecular taxonomy, assays for antimicrobial activity and presence of polyketide synthase genes.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. A large proportion of cultivable neuston actinomycetes produce antimicrobial compounds

Bacteria morphologically similar to streptomycetes were isolated from surface microlayer collected at Steinvikholmen (a small islet) and in the Åsen fjord in the Trondheim fjord, Norway. The water temperatures during sampling were 4.3 and 5.8 °C, respectively, and the air temperature was 3 °C in both cases. Water was sampled from two sites, both to increase the number of isolates and to possibly detect any spatial variations in diversity. Collecting water samples close to the shore increases the risk of cultivating terrestrial bacteria that have been washed into the sea. Initial isolation of the bacteria was therefore performed on agar media with 50 % seawater to increase the chance of isolating bacteria adapted to the marine environment.

Total numbers of bacteria isolated on Actinomycete isolation seawater agar with cycloheximide and nalidixic acid added to inhibit the growth of fungi and Gram-negative bacteria, were 2.5x103 and 1.2x104 cells/ml seawater from the two sites, respectively. Presumed actinomycetes (based on colony morphology) accounted for 9.8x102 and 1.3x103 cells/ml, respectively. From these, a total of 217 colonies from samples 1 and 2 represented by 134 and 83 isolates, respectively, were selected for further analyses.

Previously, it has been reported that bacteria isolated from the surface microlayer at coastal stations in the north-western Mediterranean Sea, contained an average of Gram-positive cultivable bacteria ranging from 2.3x103 (France) to 3.0x104 (Spain) ml−1 [15], indicating that the cell number can vary considerably depending on the sampling site. Based on these reports, the total number of isolates in the samples collected in this study is assumed to reflect at least some of the diversity in the Trondheim fjord.

Based on the colony morphology (colour of substrate and aerial mycelia, pigment production), the isolates could be divided into 10 groups, shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the different isolate groups, when grown on ½ISP2 medium with 50% seawater for up to 14 days. SM = substrate mycelium, AM = aerial mycelium

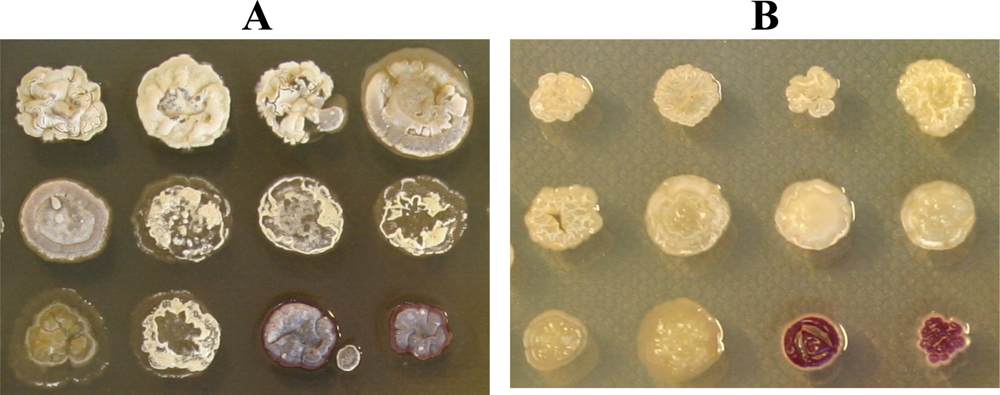

Cultivation of the isolates on agar medium with and without seawater, showed that they all grew better/faster on media with 50 % seawater added, as exemplified on Figure 1. Actinomycetes isolated from marine sediments have earlier been analyzed for their seawater requirement for growth [16]. The detected requirement has been interpreted as indication of marine origin or marine adaptation. None of the isolates in this study demonstrated inhibited growth on salt-containing media, suggesting that all isolates are marine bacteria or terrestrial bacteria adapted to the marine environment, and presumably occur naturally in the surface microlayer.

Figure 1.

Growth of isolated actinomycetes after 7 days of incubation at 30 °C on ½ ISP2 agar with (A) and without (B) 50% seawater.

In order to explore the potential of the isolates to produce antimicrobial compounds, extracts from the colonies grown on three different solid agar media were tested in microbial inhibition assays. After an appropriate incubation time (depending on the growth rate), the plates with cells were dried, and extracted with DMSO. The extracts were tested in agar diffusion assays for antimicrobial activity. The initial assays were performed with Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341, Candida albicans ATCC 10231 and Escherichia coli K12 as indicator organisms. The antimicrobial activity, presented in Table 2, is the total combined activity displayed by the isolates when grown on any of the 3 agar media. As expected, a high share of the isolates exhibited antimicrobial activity. In particular, 79% of the sample 1 isolates, and 85% of the sample 2 isolates showed antagonistic activity against at least one of the indicator organisms. Several of the isolates showing antimicrobial activity were active against more than one indicator organism, as shown in Table 2. This was particularly evident for the isolates with antibacterial activity, where around 80% of the isolates inhibiting Gram-negative bacteria also inhibited Gram-positive bacteria, and vice versa. Table 2 shows how the different inhibition patterns are distributed among the isolates from different morphological groups. The fact that some isolates displayed activity against more than one indicator organism may indicate production of several antimicrobial compounds and/or production of compounds with multiple microbial targets.

Table 2.

Total number of streptomycete-like isolates from bacterioneuston, sample 1 and 2, grouped and sub-grouped according to antimicrobial activity and colony morphology. DMSO-extracts from all strains were tested for activity against C. albicans (C), M. luteus (M) and E. coli (E). Samples 1 and 2 contain 134 and 83 isolates, respectively S1 and S2 indicate sample 1 and sample 2, and G1-G10 indicate morphology groups 1- 10, (see Table 1). The percentages (S1 and S2 combined) of antifungal, antibacterial and no activity in each of the groups, G1-G10, are also given.

The percentage of neuston actinomycete isolates displaying antimicrobial activity was found to be considerably higher than those reported previously. In the earlier studies, about 50% of isolated marine pelagic bacteria exhibited antagonistic properties against other pelagic bacteria [8], and only 44 % of streptomycetes from the marine sediments have shown antibacterial activity [17]. In the latter study, 17% of the isolates displayed antifungal activity. A noticeably lower degree of antifungal compared to antibacterial activity among Streptomyces species isolated from marine sediments has also been reported by [18]. In our study, about 40% of the assumed (based on morphology and inhibition patterns) non-identical isolates from both sample 1 and 2 showed antifungal activities.

The methods chosen for surface sampling and cultivation may facilitate isolation of some types of bacteria over others. This will affect both the quantity and the diversity of the samples. Isolates from group G1 were frequently found in both samples. This may be due both to the fact that the selected growth conditions were best suited for the G1 isolates, and that they were in fact abundant in the surface microlayer. The diversities of streptomycete-like bacteria within the samples 1 and 2, at least as judged from colony morphology and inhibition patterns, were quite similar. This is probably not surprising, considering that the currents in the fjord continuously mix the water, thereby homogenizing the content of bacterioneuston to some extent.

Groups G5 and G6 had the highest share of isolates without any detectable antimicrobial activity under the conditions used. About half of these isolates displayed neither antifungal nor antibacterial activity. In both groups, one third of the isolates showed antifungal activity. Similarity in inhibition patterns was also noticeable between the G8 and G9 isolates. In these two groups, all isolates exhibited antimicrobial activity, whereof two thirds showed activity against both M. luteus and E. coli, and the rest also had activity against C. albicans. In addition G3 and G4 isolates showed a high degree of antibacterial activity, 77 % and 100 %, respectively. In total these results display a weak connection between morphology and antimicrobial activity to some extent.

Analysis of the 16S rDNA from the isolated bacteria reveals discrepancy between phenotypic grouping and the molecular taxonomy.

In order to reveal the diversity among isolated actinomycetes, a limited analysis of 1351 nt 16S rDNA gene fragments was performed. In total, 16S rDNA fragments from 46 isolates representing different groups distinguishable by morphology and inhibition patterns were amplified and sequenced. Alignment of the sequences showed a relatively high degree of homology within the candidate collection, suggesting replication of some isolates. However, several of the isolates representing potential replicates based on the 16S rDNA sequence, displayed unique inhibition patterns, indicating that they are not identical.

BLAST searches for the obtained sequences showed that the 16S rDNAs from all except 4 isolates had at least 99 % identity to sequences from Streptomyces spp isolated from marine sediments and sponges [19-22]. A widespread distribution of these bacteria in marine environments is consistent with the fact that they thrive on the salt-containing media.

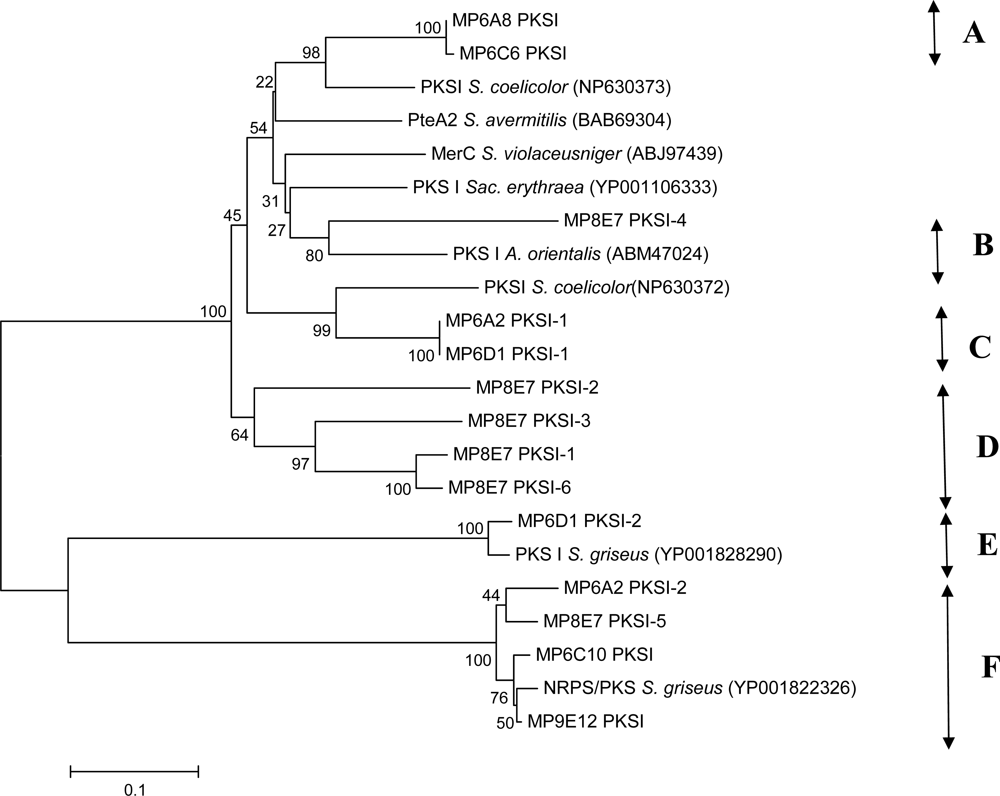

A phylogenetic analysis of the partial 16S rDNA sequences, displayed in Figure 2, was performed to reveal the taxonomic relationship between the different subgroups. In cases where several isolates had identical sequences, only one sequence was included in the analysis, without regard to differences in the morphology and inhibition patterns. As noted above, at least 10 morphologically different groups could be distinguished among the isolates. No clustering of these groups was observed in the phylogenetic analysis. Only minor grouping of isolates sharing the same inhibition patterns could be found. However, some clustering of isolates displaying either antifungal or antibacterial activity could be identified. In several cases, the “closest match” strains were reported to have antimicrobial activity that may be interesting from a commercial point of view.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree constructed for partial 16S rDNA sequences (1351 bp) of 46 streptomycetes isolated from the surface microlayer in the Trondheim fjord, Norway. The tree also contains some of the closest matches from BLAST searches. The 16S rDNA sequence from Micromonospora sp DSM 44397 is included to root the tree. Numbers in brackets (x-y-z) refers to x: morphology group, y: inhibition pattern (see table 2), and z: sample number. Arrows indicate the different branches of the tree. Bold font indicates sequences representing several isolates. Strains of marine origin are underlined.

Sequence for the isolate MP7A10 represents a group of six isolates, whereof five appear to have the same morphology (group G6). These isolates display different inhibition patterns, strongly suggesting that 16S rDNA gene sequences alone can not be used for dereplication of isolates.

Sequence for the isolate MP6A8 represents ten isolates with varying morphology (group G1-G5 and G10), of which eight were shown to have antibacterial activity. Including the remaining isolates in branch 1, a total of 17 out of 23 isolates in this branch displayed antibacterial activity, of which 15 were active against Gram–positive, and 2 against Gram-negative bacteria.

Three out of four isolates in branch 3 displayed antibacterial activity. The deviating isolate did not show any antimicrobial activity under the conditions tested. Sequence for isolate MP7E8 represents an additional isolate with the same inhibition pattern. Branch 4 and 5 consisted of isolates displaying both varying morphology and inhibition patterns. Isolate MP5D9 represents a group of 13 isolates whereof 8 displayed antifungal activity. There was a considerable variation in morphology among these isolates.

Several of the isolates with antibacterial activity (MP8F7, MP7E10, MP7B7, MP7E8 and MP9C8) showed 99 and 100% identity to Streptomyces species isolated from coastal sediments [19], but no antimicrobial activity has been reported for these species.

The sequence from isolate MP5F10 having antifungal activity showed 99% identity to Streptomyces olivoviridis and Streptomyces sp. N0028. The cultural appearance of S. olivoviridis agrees with that of MP5F10. This strain has been shown to produce a new antitumor antibiotic, thioviridamide, stimulating apoptosis signalling [23].

16S rDNA from the isolate MP9D2, which inhibits growth of Gram-positive bacteria, was 100% identical to that of S. drozdowiczii and Streptomyces sp. WL-2 (1351 bases). S. drozdowiczii NRRL B-24297 was reported to have cellulolytic activity [24], while Streptomyces sp. WL-2 produces xylanase [25].

16S rDNA from the isolate MP8F10 was 99% identical to S. zaomyceticus XSD-118. Different S. zaomyceticus strains have been shown to produce foroxymithine, narbomycin, picromycin and methymycin. Foroxymithine is an inhibitor of angiotensin-converting enzyme produced by actinomycetes, and may be of interest for medical use [26]. 16S rDNA from the isolate MP5H12 shows 99 % similarity to S. microflavus 173958.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Sampling and isolation of Streptomycete bacteria from sea surface microlayer (Sampling sites and sample collection)

Samples were collected on the 22nd of March 2004 at two sites (63°32,511 N, 010°48,797 E and 63º56,009 N, 010º91,020 E) in the Trondheim fjord, Norway. Steinvikholmen (sample 1) is a small islet situated approximately 200 m from the mainland, whereas the other sampling point was close to shore. The surface microlayer was collected using Teflon plates as earlier described [39]. The plates were immersed in water, gently lifted through the water surface, and the bacterioneuston scraped off using a rubber edge. Both samples were collected early in the morning during low tide, and 2 to 3 meters from the shoreline.

Samples were plated on selective agar plates (2% w/v), within 24 hours after collection, and was incubated at 20 ºC. Three different media was used; ½ ISP2; Malt extract (5 g), yeast extract (2 g), glucose (2 g), natural sea water (0.5 L) and distilled water (0.5 L), Kusters streptomycete isolation medium (modified); Glycerol (10 g), Casein (0.3 g), KNO3 (2 g), FeSO4*7 H2O (0.25 mg), H2SO4 (0.5 mg), natural sea water (0.5 L) and distilled water (0.5 L) and Actinomycete isolation medium without MgSO4 [40]. The pH of the isolation media was adjusted to pH 8.2. All media contained 50% sea water and was supplied with Cycloheximide (50 μl/ml) and Nalidixic acid (30 μl/ml). Selected isolates were transferred to ½ ISP2 agar to ensure pure colonies, and incubated for 16 days before storing as glycerol stock in micro well plates at −80 °C.

3.2. Extraction and antimicrobial assay

The selected strains were transferred to microwell filter plates (Nunc Silent screen nr 256073, Loprodyne 3.0 μm) with 80 μl of three different 1% agarose media (production media) to facilitate production of secondary metabolites. The production media (PM) were: PM2; Mannitol (20 g), soya bean flour (20 g), Clerol (antifoam, 0.5 g), dry yeast (3.4 g), agarose (10.0 g), tap water (1 L), PM3; Oatmeal (20 g), glycerol (2.5 g), FeSO4·7H2O (0.1 mg), MnCl2·4H2O (0.1 mg), ZnSO4·7H2O (0.01 mg), H2SO4 (0.1 mg), agarose (10 g), tap water (1 L), PM4; glucose (0.5 g), glycerol (2.5 g), oatmeal (5.0 g), soybean meal (5.0 g), yeast extract (1 g), casaminoacids (2.0 g), CaCO3 (1.0 g), Clerol (0.2 g), agarose (10 g) and tap water (1 L).

After an appropriate incubation time, 3 mm glass beads were added to the plates, and the strains were dried in the dark over night before extraction with 150 μl DMSO. The plates were shaken for 2 h at 1000 rpm before vacuum filtration (Event 4160, Eppendorf). These extracts were stored at −20 °C, and tested in agar diffusion assays for content of antagonistic compounds active against Micrococcus luteus (ATCC 9341), Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) and Escherichia coli K12.

A variant of Burkholder agar diffusion assay [41] was used when screening for antimicrobial activity. Indicator agarose was prepared by mixing 1% agarose medium with 0.5-1% v/v indicator organism culture (OD600 = 3,6 M. luteus, 5,0 C. albicans, 3,0 E. coli.), and poured into Petri dishes. LB agarose medium was used for E. coli, M19 for C. albicans and M1 for M. luteus. The media contained: M1; peptone (6.0 g), trypton (4.0 g), yeast extract (3.0 g), beef extract (1.5 g), dextrose (1.0 g), agarose (10 g) and tap water (1 L), pH 6,6. M19; beef extract (2.4 g), yeast extract (4.7 g), peptone (9.4 g), dextrose (10.0 g), NaCl (10.0 g), agarose (10 g) and tap water (1 L), pH 6,1.

DMSO-extracts were stamped manually from microwell plates onto the indicator agarose with the selected indicator organism. Approximately 2 μl of each extract was applied onto plates with 1.3 cm thick indicator agarose. The plates were preincubated for 3 to 4h at 4 °C, before incubating at 30 ºC over night. Extracts were defined as inhibiting if inhibition zones were ≥2mm larger than the diameter of the applied sample.

3.3 Cloning, sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

Based on morphology and inhibition patterns from the antimicrobial assays, subgrouping was performed, and candidates from each subgroup sequenced. PCR was performed directly on colonies or with isolated total-DNA as template. Total-DNA of the bacteria was isolated using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

The primers BP_F27: 5’-AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG-3’ and BP_R1492: 5’-TAC GGY TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3’ [42], were used to amplify 1,5 kb of the 16S rRNA gene. The PCR was performed using initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 45 seconds, 55 °C for 20 seconds and 66 °C for 2 minutes. A final extension was performed at 70 °C for 5 minutes. PCR products were purified directly or after excision from agarose gel, using QIAquick Spin Kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). Purified PCR-products were transformed into E. coli EZ competent cells after ligation into the pDrive cloning vector using the QIAGEN PCR-cloning Kit (Qiagen).

The 16S rRNA fragments were sequenced either from the pDrive-clones or directly after PCR. The primer M13 reverse: 5′-AACAGCTATGACCATG-3′ described in the Qiagen PCR Cloning Handbook (04/2001) was used for the pDrive-clones. Sequencing directly on the PCR products were performed with the same primers as for the PCR. The sequencing was performed using BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). The sequencing program consisted of a initial step at 96 °C for 3 minutes, and 25 cycles of 96 °C for 30 seconds, 50 °C for 20 seconds and 60 °C for 4 minutes.

The phylogenetic analyses of the cloned sequences were performed using MEGA 4. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using neighbour-joining with 500 bootstrap replicates. Comparisons of the sequences with other available 16S rDNA sequences were done by BLAST searches to determine strain homology. The 16S rDNA sequence from Micromonospora sp DSM 44397 was included to root the tree.

3.4 PCR amplification of PKS and NRPS-genes

Bacterial modular type I PKS genes were amplified with the degenerate primers KSMA-F (5’-TS GCS ATG GAC CCS CAG CAG-3’) and KSMB-R (5’-CC SGT SCC GTG SGC CTC SAC-3’) [31]. PCR with these primers, amplifying the β-ketoacyl synthase (KS) domain (~700 bp), was performed using initial denaturation at 96 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 95 ºC for 1 min, 60 ºC for 1 min and 72ºC for 2 min. Final extension was performed at 72 ºC for 5 min.

For each reaction 200 μM dNTPs 20-40 ng total-DNA and 200 nM of each primer were used. Cloning of the fragments was performed as described for 16S rDNA Sequencing was performed by Eurofins MWG Operon.

3.5 Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

DNA sequences reported in this study have been deposited to GenBank under accession numbers FJ190540-FJ190569

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway.

References and Notes

- Bull, AT; Stach, JEM. Marine actinobacteria: new opportunities for natural product search and discovery. TRENDS Microbiol 2007, 15, 491–499. [Google Scholar]

- Kelecom, A. Secondary metabolites from marine microorganisms. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc 2002, 74, 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, H-P; Bruntner, C; Bull, AT; Goodfellow, AC; Potterat, O; Puder, C; Mihm, G. Marine actinomycetes as a source of novel secondary metabolites. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2005, 87, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, ML; Dopazo, CP; Toranzo, AE; Barja, JL. Competitive dominance of antibiotic-producing marine bacteria in mixed cultures. J Appl Bacteriol 1991, 71, 228–232. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J. The production of antibiotics in soil. IV. Production of antibiotics in coats of seeds sown in soil. Ann. Appl. Biol 1956, 44, 561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Thomashow, LS; Weller, DM; Bonsall, RF; Oierson, LS. Production of the antibiotic phenazine-1-carboxylic acid by fluorescent Pseudomonas species in the rhizosphere of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1990, 56, 908–912. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, JR; Mitchell, JG; Pearson, L; Waters, RL. Heterogeneity in bacterioplankton abundance from 4.5 millimetre resolution sampling. Aquat. Microb. Ecolo 2000, 22, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Long, RA; Azam, F. Antagonistic interactions among marine pelagic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2001, 67, 4975–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, JT; Word, JQ. Sea surface toxicity in Puget Sound. Puget Sound Notes. U.S. EPA Region 10: Seattle, WA, 1986; pp. 3–6, (As cited by GESAMP, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth, J. Distribution and activity of oceanic bacteria. Deep-Sea Res. 1971, 18, 1111–1121, (as cited by GESAMP, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Bezdek, HF; Carlucci, AF. Surface concentrations of marine bacteria. Limnol. Oceanogr 1972, 17, 566–569. [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth, J; Willis, PJ; Johnson, KM; Burney, CM; Lavoie, DM; Hinga, K R; Caron, DA; French, FW; Johnson, PW; Davis, PG. Dissolved organic matter and heterotrophic microneuston in the surface microlayers of the North Atlantic. Science 1976, 194, 1415–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci, AF; Craven, DB; Henrichs, SM. Surface-film microheterotrophs: amino acid metabolism and solar radiation effects on their activities. Mar. Biol 1985, 85, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Amann, RI; Ludwig, W; Schleifer, KH. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 59, 143–169. [Google Scholar]

- Agoguè, H; Casamayor, EO; Bourrain, M; Obernosterer, I; Joux, F; Herndl, GJ; Lebaron, P. 2005. A survey on bacteria inhabiting the sea surface microlayer of coastal ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Ecolo 2005, 54, 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, PR; Gontang, E; Mafnas, C; Mincer, TJ; Fenical, W. Culturable marine actinomycete diversity from tropical Pacific Ocean sediments. Environ. Microbiol 2005, 7, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Peela, S; Kurada, VVSNB; Terli, R. Studies on antagonistic marine actinomycetes from the Bay of Bengal. World J. of Microbiol. & Biotechnol. 2005, 21, 583–585. [Google Scholar]

- Sponga, F; Cavaletti, L; Lazzarini, A; Borghi, A; Ciciliato, I; Losi, D; Marinelli, F. Biodiversity and potentials of marine-derived microorganisms. J. Biotechnol 1999, 70, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H; Goodacre, R. Characterization of Streptomyces spp. isolated from coastal sediments. Unpublished. Submitted to GenBank 20.09.2004.

- Jensen, PR; Prieto-Davo, A; Fenical, W. Marine Derived Actinomycete Diversity. Unpublished. Submitted to GenBank 09.10.2007.

- Hong, K; Burgess, JG. Actinomycetes isolated from sediments collected in west coast of Scotland. Unpublished. Submitted to GenBank 24.04.2006.

- Zhang, H; Zhang, W; Jin, Y; Jin, M; Yu, X. A comparative study on the phylogenetic diversity of culturable actinobacteria isolated from five marine sponge species. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2008, 93, 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, Y; Sasaki, K; Adachi, H; Furihata, K; Nagai, K; Shinya, K. Thioviridamide, a novel apoptosis inducer in transformed cells from Streptomyces olivoviridis. J. Antibiotics 2006, 59, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Semêdo, LTAS; Gomes, RC; Linhares, AA; Duarte, GF; Nascimento, RP; Rosado, AS; Margis-Pinheiro, M; Margis, R; Silva, KRA; Alviano, CS; Manfio, GP; Soares, RMA; Linhares, LF; Coelho, RRR. Streptomyces drozdowiczii sp. nov., a novel cellulolytic streptomycete from soil in Brazil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 2004, 54, 1323–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, K-H; Lee, E-H; Kim, C-J; Yoon, K-H. Characterization and xylanase productivity of Streptomyces sp. WL-2. Han'gug mi'saengmul saengmyeong gong haghoeji 2005, 33, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa, H; Takeuchi, T; Aoyagi, T; Hamada, M; Ogawa, K; Iinuma, H. The novel physiologically active substance foroxymithine, a process and microorganisms for its production and its use as medicament. European Patent EP0162422.

- Schirmer, A; Gadkari, R; Reeves, CD; Ibrahim, F; DeLong, EF; Hutchinson, CR. Metagenomic analysis reveals diverse polyketide synthase gene clusters in microorganisms associated with the marine Sponge. Discodermia dissolute. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2005, 71, 4840–4849. [Google Scholar]

- Busti, E; Monciardini, P; Cavaletti, L; Bamonte, R; Lazzarini, A; Sosio, M; Donadio, S. Antibiotic-producing ability by representatives of a newly discovered lineage of actinomycetes. Microbiol 2006, 152 Pt 3, 675–683. [Google Scholar]

- Wawrik, B; Kerkhof, L; Zylstra, GJ; Kukor, JJ. Identification of unique type II polyketide synthase genes in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2005, 71, 2232–2238. [Google Scholar]

- Bredholdt, H; Galatenko, OA; Engelhardt, K; Fjaervik, E; Terekhova, LP; Zotchev, SB. Rare actinomycete bacteria from the shallow water sediments of the Trondheim fjord, Norway: isolation, diversity and biological activity. Environ Microbiol 2007, 9, 2756–2764. [Google Scholar]

- Izumikawa, M; Murata, M; Tachibana, K; Ebizuka, Y; Fujii, I. Cloning of modular type I polyketide synthase genes from salinomycin producing strain of Streptomyces albus. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chem 2003, 11, 3401–3405. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y; Hong, H; Samboskyy, M; Mironenko, T; Leadlay, PF; Haydock, SF. Organization of the biosynthetic gene cluster in Streptomyces sp. DSM 4137 for the novel neuroprotectant polyketide meridamycin. Microbiol 2006, 152, 3507–3515. [Google Scholar]

- Oliynyk, M; Samborskyy, M; Lester, JB; Mironenko, T; Scott, N; Dickens, S; Haydock, SF; Leadlay, PF. Complete genome sequence of the erythromycin-producing bacterium Saccharopolyspora erythraea NRRL23338. Nat. Biotechnol 2007, 25, 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, H; Ishikawa, J; Hanamoto, A; Shinose, M; Kikuchi, H; Shiba, T; Sakaki, Y; Hattori, M; Omura, S. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the industrial microorganism Streptomyces avermitilis. Nat Biotechnol 2003, 21, 526–531. [Google Scholar]

- Banskota, AH; Mcalpine, JB; Sorensen, D; Ibrahim, A; Aouidate, M; Piraee, M; Alarco, AM; Farnet, CM; Zazopoulos, E. Genomic analyses lead to novel secondary metabolites. Part 3. ECO-0501, a novel antibacterial of a new class. J. Antibiot 2006, 59, 533–542. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlik, K; Kotowska, M; Chater, KF; Kuczek, K; Takano, E. A cryptic type I polyketide synthase (cpk) gene cluster in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Arch. Microbiol 2007, 187, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi, Y; Ishikawa, J; Hara, H; Suzuki, H; Ikenoya, M; Ikeda, H; Yamashita, A; Hattori, M; Horinouchi, S. Genome sequence of the streptomycin-producing microorganism Streptomyces griseus IFO 13350. J. Bacteriol 2008, 190, 4050–4060. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, MC; Neilan, BA. Evolutionary affiliations within the superfamily of ketosynthases reflect complex pathway associations. J. Mol. Evol. 2003, 56, 446–457. [Google Scholar]

- Kjelleberg, S; Stenström, TA; Odham, G. Comparative study of different hydrophobic devices for sampling lipid surface films and adherent microorganisms. Mar. Biol 1979, 53, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Atlas, RM. Handbook of Microbiological Media, 2nd Ed ed; CRC Press, Inc: New York, NY, 1997; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder, P; Pfister, R; Leitz, F. Production of a pyrrole antibiotic by a marine bacterium. Appl. Microbiol 1966, 14, 649–653. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, DJ. 16S/23S rRNA Sequencing. In Nucleic acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics; Stackebrandt, E, Goodfellow, M, Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1991; pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]