Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava Regulate Dual Signaling Pathways, IL-17RA/Act1 and ERK1/2, to Suppress Ovarian Cancer Progression and Tumor-Associated Macrophage Activation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

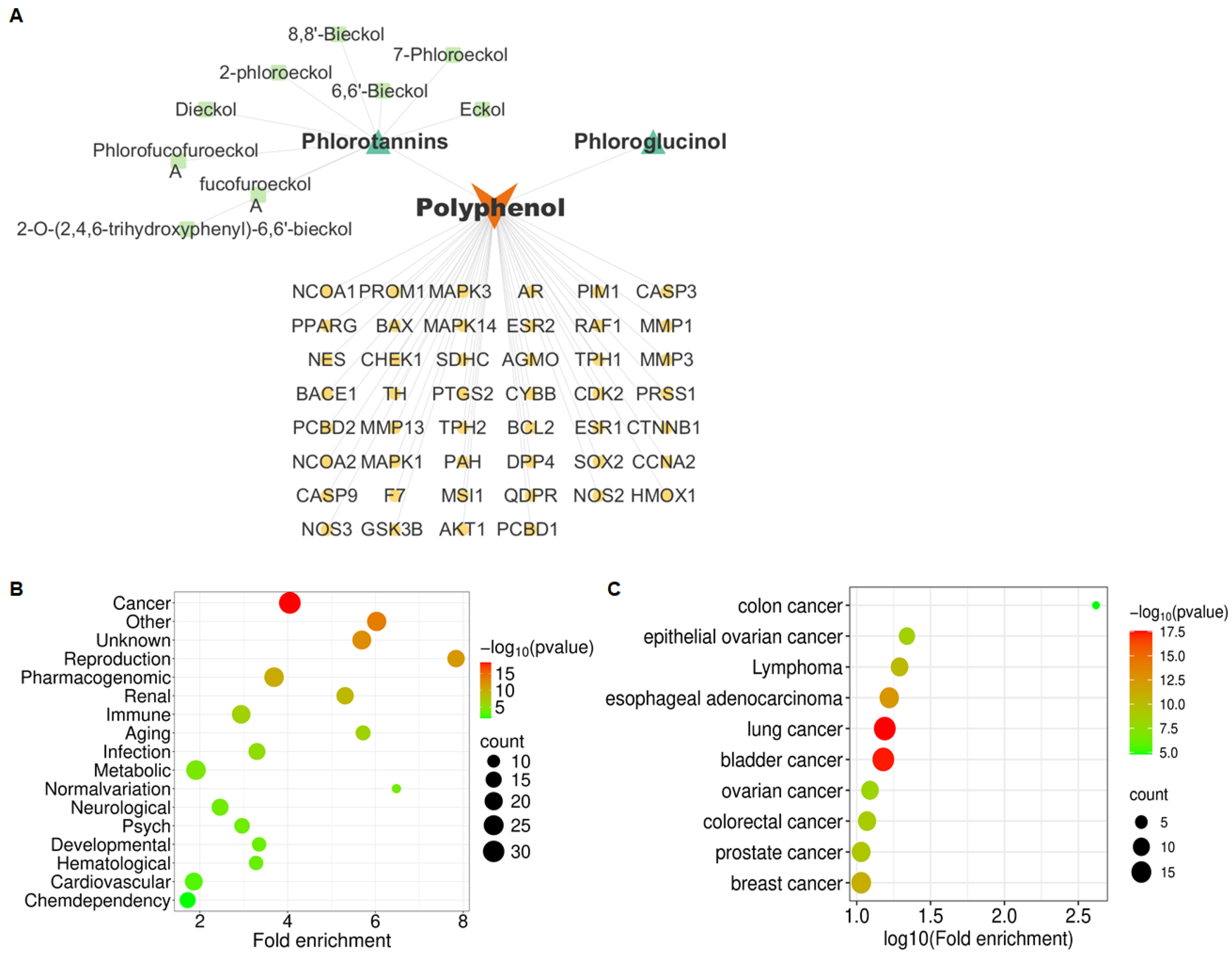

2.1. Phlorotannins Are Predicted to Be Associated with OVCA Metastasis via IL-17 Signaling Pathway

2.2. Phlorotannins Attenuate the Migratory and Invasive Ability of OVCA Cells

2.3. IL-17 Signaling Pathway Is Involved in the Phlorotannin-Inhibited Migration and Invasion of OVCA Cells

2.4. ERK1/2 Pathway Is Involved in Phlorotannin-Inhibited OVCA Cell Invasion

2.5. Phlorotannins Attenuate the Pro-Tumoral Activity of TAMs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Target Gene Screening and Network Construction

4.3. GAD Disease, KEGG Pathway, and GO Function Enrichment Analysis

4.4. Survival Analysis

4.5. Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation

4.6. Cell Culture

4.7. MTT Assay

4.8. Wound-Healing Assay

4.9. Transwell Invasion Assay

4.10. Gelatin Zymography

4.11. Western Blot Analysis

4.12. Real-Time RT-PCR

4.13. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| AR | Androgen receptor |

| BCL2 | BCL2 apoptosis regulator |

| CCNA2 | Cyclin A2 |

| CDK2 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 |

| CHEK1 | Checkpoint kinase 1 |

| CTNNB1 | Catenin beta 1 |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DPP4 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 |

| E. cava | Ecklonia cava |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 |

| ESR1 | Estrogen receptor 1 |

| ESR2 | Estrogen receptor 2 |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GAD | Genetic association database |

| GAFF | General amber force field |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase 1 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-17 | Interleukin-17 |

| IL-17RA | Interleukin-17 receptor A |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes And Genomes |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MAPK1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| MMP1 | Matrix metalloproteinases 1 |

| MMP2 | Matrix metalloproteinases 2 |

| MMP3 | Matrix metalloproteinases 3 |

| MMP9 | Matrix metalloproteinases 9 |

| MMP13 | Matrix metalloproteinases 13 |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| NCOA1 | Nuclear receptor coactivator 1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-kappa B |

| NOS2 | Nitric oxide synthase 2 |

| OVCA | Ovarian cancer |

| p38 | p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PMA | Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate |

| PMSF | Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride |

| PPARG | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PTGS2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 |

| RANTES | Regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TIMPs | Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TRAF6 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Ahn, J.H.; Yang, Y.I.; Lee, K.T.; Choi, J.H. Dieckol, isolated from the edible brown algae Ecklonia cava, induces apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells and inhibits tumor xenograft growth. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 141, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Yang, H.; Jeon, Y.J.; Lee, C.J.; Jin, Y.H.; Baek, N.I.; Kim, D.; Kang, S.M.; Yoon, M.; Yong, H.; et al. Phlorotannins of the edible brown seaweed Ecklonia cava Kjellman induce sleep via positive allosteric modulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A-benzodiazepine receptor: A novel neurological activity of seaweed polyphenols. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijesekara, I.; Yoon, N.Y.; Kim, S.K. Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava (Phaeophyceae): Biological activities and potential health benefits. BioFactors 2010, 36, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Hussain, M.B.; Tahir, A.; Waheed, M.; Anwar, A.; Shariati, M.A.; Plygun, S.; Laishevtcev, A.; Pasalar, M. Pharmacological Applications of Phlorotannins: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2021, 18, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.S.; Kim, K.J.; Park, H.; Lee, M.G.; Cho, S.; Choi, S.I.; Heo, H.J.; Kim, D.O.; Kim, G.H. Effects of Ecklonia cava Extract on Neuronal Damage and Apoptosis in PC-12 Cells against Oxidative Stress. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.A.; Jin, S.E.; Ahn, B.R.; Lee, C.M.; Choi, J.S. Anti-inflammatory activity of edible brown alga Eisenia bicyclis and its constituents fucosterol and phlorotannins in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 59, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshalkina, D.; Tsvetkova, E.; Orlova, A.; Islamova, R.; Grashina, M.; Gorbach, D.; Babakov, V.; Francioso, A.; Birkemeyer, C.; Mosca, L.; et al. First Insight into the Neuroprotective and Antibacterial Effects of Phlorotannins Isolated from the Cell Walls of Brown Algae Fucus vesiculosus and Pelvetia canaliculata. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.K.; Tang, Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Hwang, J.W.; Choi, E.J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Jeon, Y.J.; Park, P.J. First evidence that Ecklonia cava-derived dieckol attenuates MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cell migration. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 1785–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Kai, G. A review of dietary polyphenol-plasma protein interactions: Characterization, influence on the bioactivity, and structure-affinity relationship. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, N.Y.; Eom, T.K.; Kim, M.M.; Kim, S.K. Inhibitory effect of phlorotannins isolated from Ecklonia cava on mushroom tyrosinase activity and melanin formation in mouse B16F10 melanoma cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 4124–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nezhat, F.R.; Apostol, R.; Nezhat, C.; Pejovic, T. New insights in the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer and implications for screening and prevention. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, E.; Chen, S.; Corvigno, S.; Liu, J.; Sood, A.K. Ovarian cancer metastasis: Looking beyond the surface. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1631–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Chen, Y. Tumor microenvironment in ovarian cancer peritoneal metastasis. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushley, A.W.; Ferrell, R.; McDuffie, K.; Terada, K.Y.; Carney, M.E.; Thompson, P.J.; Wilkens, L.R.; Tung, K.H.; Ness, R.B.; Goodman, M.T. Polymorphisms of interleukin (IL)-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-18 and the risk of ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2004, 95, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.; Gu, L.; Ding, C.; Qiu, L.; Di, W. TWEAK promotes ovarian cancer cell metastasis via NF-kappaB pathway activation and VEGF expression. Cancer Lett. 2009, 283, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Song, J.; Gao, D.; Huang, S.; Pang, A.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Interleukin-6 and Hypoxia Synergistically Promote EMT-Mediated Invasion in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer via the IL-6/STAT3/HIF-1alpha Feedback Loop. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 2023, 2023, 8334881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Lan, T.; Chiari, C.; Ye, X.; Wang, K.; Chen, J. The role of interleukin-17 in inflammation-related cancers. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1479505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herjan, T.; Hong, L.; Bubenik, J.; Bulek, K.; Qian, W.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Ouyang, S.; et al. IL-17-receptor-associated adaptor Act1 directly stabilizes mRNAs to mediate IL-17 inflammatory signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibabaw, T.; Teferi, B.; Ayelign, B. The role of Th-17 cells and IL-17 in the metastatic spread of breast cancer: As a means of prognosis and therapeutic target. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1094823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, X.L.; Lin, W.; Mao, C.W.; Feng, Y.Z.; Kong, J.Z.; Chen, S.M. Blockade of IL-17 alleviated inflammation in rat arthritis and MMP-13 expression. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Li, J.; Wang, J.H.; Wu, Q.; Yang, P.; Hsu, H.C.; Smythies, L.E.; Mountz, J.D. IL-17 activates the canonical NF-kappaB signaling pathway in autoimmune B cells of BXD2 mice to upregulate the expression of regulators of G-protein signaling 16. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 2289–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.E.; Ahn, S.H.; Marks, R.M.; Monsanto, S.P.; Fazleabas, A.T.; Koti, M.; Tayade, C. IL-17A Modulates Peritoneal Macrophage Recruitment and M2 Polarization in Endometriosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rei, M.; Goncalves-Sousa, N.; Lanca, T.; Thompson, R.G.; Mensurado, S.; Balkwill, F.R.; Kulbe, H.; Pennington, D.J.; Silva-Santos, B. Murine CD27(-) Vgamma6(+) gammadelta T cells producing IL-17A promote ovarian cancer growth via mobilization of protumor small peritoneal macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E3562–E3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Niu, X.; Du, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, L.; Iwakura, Y.; Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, Z.; et al. IL-17A promotes fatty acid uptake through the IL-17A/IL-17RA/p-STAT3/FABP4 axis to fuel ovarian cancer growth in an adipocyte-rich microenvironment. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.C.; Kang, K.A.; Zhang, R.; Piao, M.J.; Kim, G.Y.; Kang, M.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, N.H.; Surh, Y.J.; Hyun, J.W. Up-regulation of Nrf2-mediated heme oxygenase-1 expression by eckol, a phlorotannin compound, through activation of Erk and PI3K/Akt. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Park, J.Y.; Wu, J.; Lee, J.H.; Yang, Y.S.; Kang, M.S.; Jung, S.C.; Park, J.M.; Yoo, E.S.; Kim, S.H.; et al. Dieckol Attenuates Microglia-mediated Neuronal Cell Death via ERK, Akt and NADPH Oxidase-mediated Pathways. Korean, J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 19, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Yin, Q.; Snell, A.H.; Wan, L. RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer evolution and treatment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 85, 123–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnini, S.; Morbidelli, L.; Taraboletti, G.; Ziche, M. ERK1-2 and p38 MAPK regulate MMP/TIMP balance and function in response to thrombospondin-1 fragments in the microvascular endothelium. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 2975–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.O.; Smith, S.; Chen, R.H.; Fingar, D.C.; Blenis, J. Molecular interpretation of ERK signal duration by immediate early gene products. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 4, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colvin, E.K. Tumor-associated macrophages contribute to tumor progression in ovarian cancer. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, H. Functional Ingredients from Algae for Foods and Nutraceuticals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maheswari, V.; Babu, P.A.S. Phlorotannin and its Derivatives, a Potential Antiviral Molecule from Brown Seaweeds, an Overview. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2022, 48, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.I.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, K.T.; Choi, J.H. 8,8′-Bieckol, isolated from edible brown algae, exerts its anti-inflammatory effects through inhibition of NF-kappaB signaling and ROS production in LPS-stimulated macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 23, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yang, S.; Xiao, Z.; Hong, P.; Sun, S.; Zhou, C.; Qian, Z.J. The Inhibition Effect of the Seaweed Polyphenol, 7-Phloro-Eckol from Ecklonia Cava on Alcohol-Induced Oxidative Stress in HepG2/CYP2E1 Cells. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Liu, C.; Hartupee, J.; Altuntas, C.Z.; Gulen, M.F.; Jane-Wit, D.; Xiao, J.; Lu, Y.; Giltiay, N.; Liu, J.; et al. The adaptor Act1 is required for interleukin 17-dependent signaling associated with autoimmune and inflammatory disease. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, M.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.R. Targeting the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway for cancer therapy: From mechanism to clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiyatkin, A.; van Alderwerelt van Rosenburgh, I.K.; Klein, D.E.; Lemmon, M.A. Kinetics of receptor tyrosine kinase activation define ERK signaling dynamics. Sci. Signal. 2020, 13, eaaz5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifilieff, P.; Lavaur, J.; Pascoli, V.; Kappes, V.; Brami-Cherrier, K.; Pages, C.; Micheau, J.; Caboche, J.; Vanhoutte, P. Endocytosis controls glutamate-induced nuclear accumulation of ERK. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2009, 41, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.I.; Ahn, J.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Choi, J.H. Brown algae phlorotannins enhance the tumoricidal effect of cisplatin and ameliorate cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 136, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Yang, Y.I.; Ahn, J.H.; Lee, J.G.; Lee, K.T.; Choi, J.H. Deer (Cervus elaphus) antler extract suppresses adhesion and migration of endometriotic cells and regulates MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.H.; Lee, K.T.; Choi, Y.S.; Choi, J.H. Iloprost, a prostacyclin analog, inhibits the invasion of ovarian cancer cells by downregulating matrix metallopeptidase-2 (MMP-2) through the IP-dependent pathway. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2018, 134, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Choi, J.H. Leptin promotes human endometriotic cell migration and invasion by up-regulating MMP-2 through the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 21, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dheda, K.; Huggett, J.F.; Bustin, S.A.; Johnson, M.A.; Rook, G.; Zumla, A. Validation of housekeeping genes for normalizing RNA expression in real-time PCR. Biotechniques 2004, 37, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.L.; Chang, T.C.; Chao, C.C.K.; Sun, N.K. Role of the TLR4-androgen receptor axis and genistein in taxol-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 113965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.K.; Huang, S.L.; Lu, H.P.; Chang, T.C.; Chao, C.C. Integrative transcriptomics-based identification of cryptic drivers of taxol-resistance genes in ovarian carcinoma cells: Analysis of the androgen receptor. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 27065–27082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, R.; Wilander, E.; Oberg, K. Expression and prognostic significance of Bcl-2 in ovarian tumours. Br. J. Cancer 1995, 72, 1324–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herod, J.J.; Eliopoulos, A.G.; Warwick, J.; Niedobitek, G.; Young, L.S.; Kerr, D.J. The prognostic significance of Bcl-2 and p53 expression in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 2178–2184. [Google Scholar]

- Beale, P.J.; Rogers, P.; Boxall, F.; Sharp, S.Y.; Kelland, L.R. BCL-2 family protein expression and platinum drug resistance in ovarian carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2000, 82, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. IL-17A/lL-17RA reduces cisplatin sensitivity of ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells by regulating autophagy. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2020, 4, 1550–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, K.; Li, M.; Cui, L.; Liu, G.; Yan, Y.; Tian, W.; Teng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, C.; et al. miR-508-3p suppresses the development of ovarian carcinoma by targeting CCNA2 and MMP7. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 57, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, P.J.; Zhao, J.H.; Xie, L.L. Cul4B promotes the progression of ovarian cancer by upregulating the expression of CDK2 and CyclinD1. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, V.E.; Moore, S.L.; Chen, M.; House, N.; Ramsden, P.; Wu, H.J.; Ribich, S.; Grassian, A.R.; Choi, Y.J. CDK2 regulates collapsed replication fork repair in CCNE1-amplified ovarian cancer cells via homologous recombination. NAR Cancer 2023, 5, zcad039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.Y.; Kim, Y.B.; Park, W.H.; No, J.H. Enhanced Efficacy of Combined Therapy with Checkpoint Kinase 1 Inhibitor and Rucaparib via Regulation of Rad51 Expression in BRCA Wild-Type Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 53, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, G.; Mani, C.; Sah, N.; Saamarthy, K.; Young, R.; Reedy, M.B.; Sobol, R.W.; Palle, K. CHK1 inhibitor induced PARylation by targeting PARG causes excessive replication and metabolic stress and overcomes chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Wu, R.; Schwartz, D.R.; Darrah, D.; Reed, H.; Kolligs, F.T.; Nieman, M.T.; Fearon, E.R.; Cho, K.R. Role of beta-catenin/T-cell factor-regulated genes in ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 160, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Gao, Z.W.; Liu, Y.Q.; Yang, L.; Wu, X.N.; Dong, K.; Zhu, X.M. Down-regulation of DPP4 by TGFbeta1/miR29a-3p inhibited proliferation and promoted migration of ovarian cancer cells. Discov. Oncol. 2023, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiyama, H.; Shibata, K.; Ino, K.; Mizutani, S.; Nawa, A.; Kikkawa, F. The expression of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV/CD26) is associated with enhanced chemosensitivity to paclitaxel in epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2010, 101, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; Cai, Q.; Deng, Y.; Shi, W.; Zhou, H.; Wang, D.; Li, J. Isorhamnetin inhibits progression of ovarian cancer by targeting ESR1. Ann Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinton, G.; Nilsson, S.; Moro, L. Targeting estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) for treatment of ovarian cancer: Importance of KDM6B and SIRT1 for ERbeta expression and functionality. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, G.; Wilkens, L.R.; Thompson, P.J.; Shvetsov, Y.B.; Matsuno, R.K.; Carney, M.E.; Palmieri, R.T.; Wu, A.H.; Pike, M.C.; Pearce, C.L.; et al. Estrogen receptor beta rs1271572 polymorphism and invasive ovarian carcinoma risk: Pooled analysis within the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler-Toprak, S.; Weber, F.; Skrzypczak, M.; Ortmann, O.; Treeck, O. Estrogen receptor beta is associated with expression of cancer associated genes and survival in ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Peng, Z.; Liu, W.; Yang, Z.; Shang, J.; Cui, L.; Duan, F. Evaluation of the epidemiological and prognosis significance of ESR2 rs3020450 polymorphism in ovarian cancer. Gene 2019, 710, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lu, J.; Xue, J.; Liu, P. High expression of HO-1 predicts poor prognosis of ovarian cancer patients and promotes proliferation and aggressiveness of ovarian cancer cells. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 20, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, P.; Cheng, Q.; Chang, K.; Bao, L.; Yi, X. Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) depletion promotes ferroptosis to reverse cisplatin-resistance via enhancing NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 327, 147257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tan, R. HMOX1: A pivotal regulator of prognosis and immune dynamics in ovarian cancer. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Lee, C.J.; An, H.J.; Yoo, S.M.; Kang, H.C.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, K.D.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, H.S.; Cho, Y.Y. Magnolin targeting of ERK1/2 inhibits cell proliferation and colony growth by induction of cellular senescence in ovarian cancer cells. Mol. Carcinog. 2019, 58, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiwei, T.; Hua, H.; Hui, G.; Mao, M.; Xiang, L. HOTAIR Interacting with MAPK1 Regulates Ovarian Cancer skov3 Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion. Med. Sci. Monit. 2015, 21, 1856–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.H.; Yao, T.Z.; Liu, W. miR-378a-3p sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin through targeting MAPK1/GRB2. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.; Long, H.; He, L.; Han, X.; Lin, K.; Liang, Z.; Zhuo, W.; Xie, R.; Zhu, B. Interleukin-17 produced by tumor microenvironment promotes self-renewal of CD133+ cancer stem-like cells in ovarian cancer. Oncogene 2015, 34, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, A.; Yoshioka, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ishikawa, M.; Ikeda, S.I.; Kato, T.; Kiyono, T.; Takeshita, F.; Kajiyama, H.; Kikkawa, F.; et al. Malignant extracellular vesicles carrying MMP1 mRNA facilitate peritoneal dissemination in ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Shen, W.; Wu, Q. Identification of Quercetin as a Natural MMP1 Inhibitor for Overcoming Cisplatin Resistance in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. J. Cancer 2025, 16, 2578–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Ren, J.; Zhao, M. Plasma proteomes and metabolism with genome-wide association data for causal effect identification in ovarian cancer. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Q.; Lian, X.; Jiang, P.; Cui, J. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha) Promotes Hypoxia-Induced Invasion and Metastasis in Ovarian Cancer by Targeting Matrix Metallopeptidase 13 (MMP13). Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 7202–7208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Serrano, M.; Flores-Colon, M.; Valiyeva, F.; Melendez, L.M.; Vivas-Mejia, P.E. Upregulation of MMP3 Promotes Cisplatin Resistance in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H.; Hayakawa, J.; Terai, Y.; Kanemura, M.; Tanabe-Kimura, A.; Kamegai, H.; Seino-Noda, H.; Ezoe, S.; Matsumura, I.; Kanakura, Y.; et al. Difference between genomic actions of estrogen versus raloxifene in human ovarian cancer cell lines. Oncogene 2008, 27, 2737–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yu, C.; Zhou, S.; Lau, W.B.; Lau, B.; Luo, Z.; Lin, Q.; Yang, H.; Xuan, Y.; Yi, T.; et al. Epigenetic repression of PDZ-LIM domain-containing protein 2 promotes ovarian cancer via NOS2-derived nitric oxide signaling. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 1408–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, B.; Ko, S.Y.; Haria, D.; Barengo, N.; Naora, H. The homeoprotein DLX4 controls inducible nitric oxide synthase-mediated angiogenesis in ovarian cancer. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizotte, P.H.; Baird, J.R.; Stevens, C.A.; Lauer, P.; Green, W.R.; Brockstedt, D.G.; Fiering, S.N. Attenuated Listeria monocytogenes reprograms M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages in ovarian cancer leading to iNOS-mediated tumor cell lysis. Oncoimmunology 2014, 3, e28926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermajer, N.; Wong, J.L.; Edwards, R.P.; Chen, K.; Scott, M.; Khader, S.; Kolls, J.K.; Odunsi, K.; Billiar, T.R.; Kalinski, P. Induction and stability of human Th17 cells require endogenous NOS2 and cGMP-dependent NO signaling. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Yao, Z.; Pan, H. PPARgamma inhibits ovarian cancer cells proliferation through upregulation of miR-125b. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 462, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, M.; Coulson, K.; Blot, C.; Jacquemin, G.; Romano, M.; Renoud, M.L.; AlaEddine, M.; Le Naour, A.; Authier, H.; Rahabi, M.C.; et al. PPARgamma activation modulates the balance of peritoneal macrophage populations to suppress ovarian tumor growth and tumor-induced immunosuppression. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, K.; Deng, L.; Liang, J.; Liang, H.; Feng, D.; Ling, B. Cyclooxygenase 2 Promotes Proliferation and Invasion in Ovarian Cancer Cells via the PGE2/NF-kappaB Pathway. Cell Transplant. 2019, 28, 1S–13S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Cheng, J.C.; Chang, H.M.; Leung, P.C. COX2 and PGE2 mediate EGF-induced E-cadherin-independent human ovarian cancer cell invasion. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2014, 21, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Qi, Y.; He, J.; Deng, L.; Chen, S.; Pan, H.; Guo, H. IL17A/F secreted by ASCT2-overexpression ovarian cancer cells contributes to immune escape through the suppression of natural killer (NK) cells cytotoxicity by the activation of c-JUN/PTGS2 pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 150, 114226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phlorotannins | IC50 1 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|

| SKOV3 | A2780 | |

| Dieckol | 88.3 ± 4.6 | 79.3 ± 0.4 |

| 8,8′-Bieckol | 95.0 ± 4.2 | 88.1 ± 0.7 |

| 7-Phloroeckol | 137.3 ± 6.1 | 135.2 ± 1.3 |

| Box_Center (x, y, z) | Affinity (kcal/mol) | Ligand Efficiency (kcal/mol) | Residue Information | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dieckol | 2.14, 0.92, −12.37 | −8.8 | −0.16 | Asp103, Ala104, Ser105, His163 |

| 8,8′-Bieckol | 2.05, −3.32, −10.91 | −8.5 | −0.16 | Asp103, Gln101, Leu107, Ser105, Thr102 |

| 7-Phloroeckol | 2.55, 1.29, −11.63 | −7.8 | −0.22 | Asp103, His163, Thr102 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, E.-H.; Lee, H.-H.; Choi, J.-H.; Ahn, J.-H. Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava Regulate Dual Signaling Pathways, IL-17RA/Act1 and ERK1/2, to Suppress Ovarian Cancer Progression and Tumor-Associated Macrophage Activation. Mar. Drugs 2026, 24, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010012

Kim E-H, Lee H-H, Choi J-H, Ahn J-H. Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava Regulate Dual Signaling Pathways, IL-17RA/Act1 and ERK1/2, to Suppress Ovarian Cancer Progression and Tumor-Associated Macrophage Activation. Marine Drugs. 2026; 24(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Eun-Hye, Hwi-Ho Lee, Jung-Hye Choi, and Ji-Hye Ahn. 2026. "Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava Regulate Dual Signaling Pathways, IL-17RA/Act1 and ERK1/2, to Suppress Ovarian Cancer Progression and Tumor-Associated Macrophage Activation" Marine Drugs 24, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010012

APA StyleKim, E.-H., Lee, H.-H., Choi, J.-H., & Ahn, J.-H. (2026). Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava Regulate Dual Signaling Pathways, IL-17RA/Act1 and ERK1/2, to Suppress Ovarian Cancer Progression and Tumor-Associated Macrophage Activation. Marine Drugs, 24(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010012