2.1. Improvement of Two-Stage Enzymatic Hydrolysis Conditions

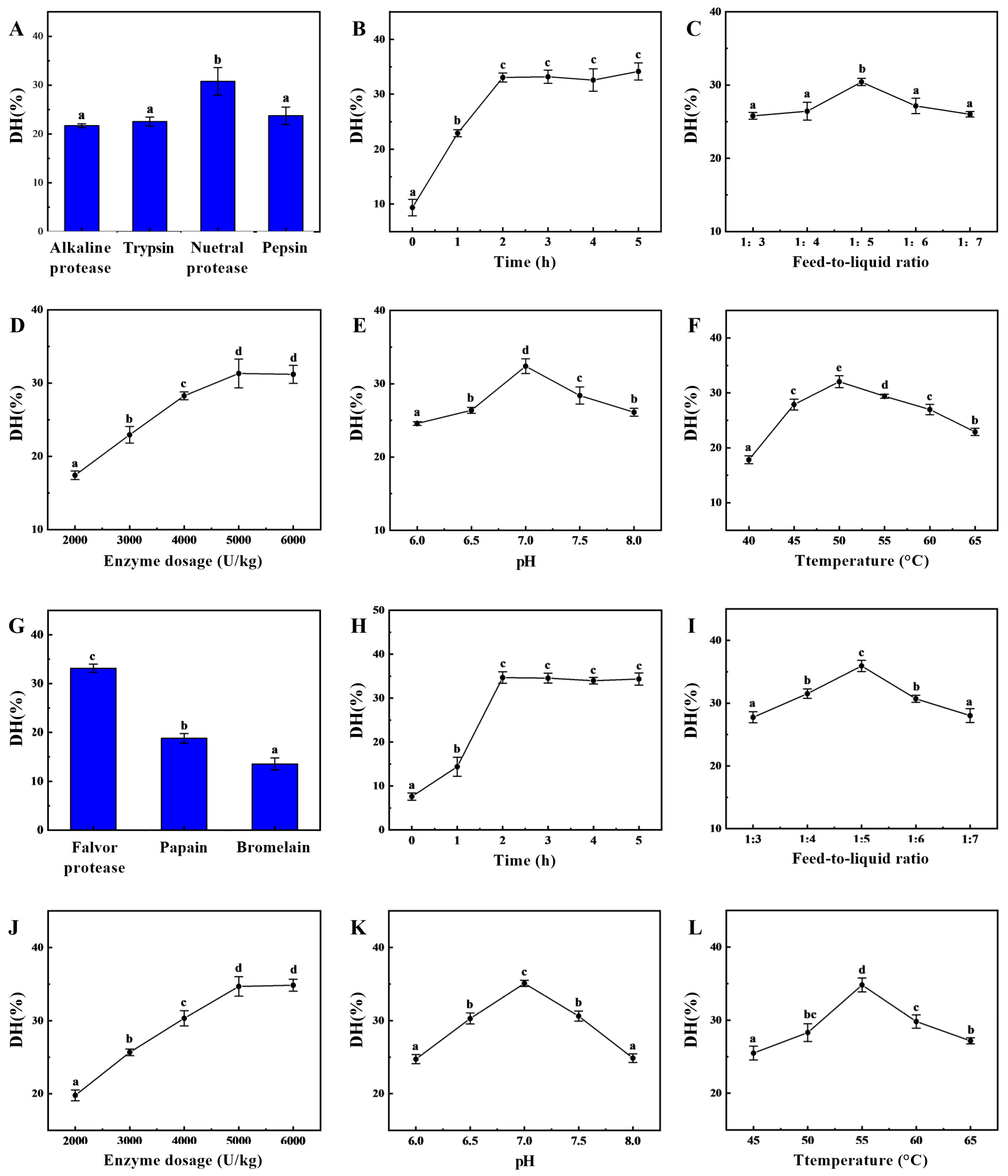

In the first stage of enzymatic hydrolysis, the type of enzyme significantly affects the degree of hydrolysis, as shown in

Figure 1A. The neutral protease produced significantly higher degree of hydrolysis than the other three endopeptidases, indicating that neutral protease had the best enzymatic hydrolysis effect, with a degree of hydrolysis of 30.78 ± 2.82%, which was similar to our previous experimental findings [

22]. During this initial stage of enzymatic hydrolysis, the substrate concentration was high, resulting in a fast hydrolysis rate and the gradual accumulation of hydrolysis products. As time progressed, the substrate concentration decreased, leading to a slower hydrolysis rate. The hydrolysis degree increased gradually before two hours (

Figure 1B), reached a peak at two hours, and then stabilized with no significant differences afterwards. The feed-to-liquid ratio directly affects enzyme activity and reaction efficiency (

Figure 1C). At an appropriate feed-to-liquid ratio, both effective substrate utilization and high enzyme activity can be maintained to promote the reaction. Between a ratio of 1:3 and 1:5, the degree of hydrolysis gradually increases. However, as the feed-to-liquid ratio increases, the degree of hydrolysis shows a decreasing trend. At higher substrate concentrations, enzyme site saturation may lead to an increase in reaction rate, but it may also enhance enzyme inhibition. The effects of different enzyme dosages on sea cucumber hydrolysis are compared (

Figure 1D). As the enzyme dosage increases, the degree of hydrolysis also gradually increases, with significant differences observed. The maximum hydrolysis degree is reached at an enzyme dosage of 5000 U/kg (31.32 ± 1.97%), after which it plateaus at dosages of 5000 U/kg and 6000 U/kg. Typically, neutral proteases exhibit optimal enzyme activity within a pH range of 6.0–8.0. If the pH is too low (acidic) or too high (alkaline), the enzyme conformation may change, causing the active site to lose function and thereby reducing enzymatic efficiency. Therefore, setting the pH to 7.0 can significantly enhance the degree of protein hydrolysis and improve the efficiency of the enzymatic process (

Figure 1E). An appropriate temperature can increase the kinetic energy of enzyme molecules, promoting their binding with substrates and enhancing the rate of enzymatic hydrolysis (

Figure 1F). However, when the temperature exceeds 65 °C, the enzyme structure may denature, leading to reduced activity or even complete inactivation. As the temperature increases from 40 °C to 50 °C, the hydrolysis rate first accelerates and then slows down. The extent to which the hydrolysis equilibrium shifts towards the forward direction is greatest at 50 °C, achieving a maximum hydrolysis degree of 32.04 ± 1.09%. Based on the above improvements, the enzymatic hydrolysis conditions for the initial stage can be determined as follows: a feed-to-liquid ratio of 1:5, an enzyme dosage of 5000 U/kg, a temperature of 50 °C, and a pH of 7.0, with hydrolysis conducted for 2 h.

Generally, a single protease exhibits selectivity toward hydrolyzing peptide bonds. To further enhance hydrolysis efficiency, secondary enzymatic hydrolysis can be employed to shift the hydrolysis site, thereby significantly improving enzymatic hydrolysis efficiency [

7].

Figure 1G–L show that the degree of hydrolysis in the composite flavor protease group was significantly higher than that in the other groups, indicating that it had the greatest capacity for degrading protein substrates, with a degree of hydrolysis of 33.18 ± 0.83%. Based on the results of the single-factor experiment, the optimal conditions for the two-stage enzymatic hydrolysis were determined to be a hydrolysis time of 3 h, a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:5, an enzyme dosage of 5000 U/kg, a pH of 7.0 and a hydrolysis temperature of 55 °C. After neutral protease hydrolysis for two hours, composite flavor protease was added, and hydrolysis continued for three hours. The hydrolysis degree then stopped increasing and reached a maximum value of 54.60 ± 1.55%, over 20% higher than the maximum achieved by single-enzyme hydrolysis. The molecular weight distribution of the enzymatic hydrolysate is shown in

Supplementary Figure S1, with a significant increase in the proportion of components below 1000 Da. This facilitates both the separation of oligopeptides from macromolecular polysaccharides and the efficient absorption and physiological function of the oligopeptides.

2.2. Separation of Sea Cucumber Polysaccharides and Peptides

The proteins in sea cucumber body walls are primarily collagen, which undergoes significant molecular weight reduction after enzymatic hydrolysis. Sea cucumber polysaccharides also constitute a vital component of the body wall, primarily residing in the extracellular matrix. They account for 6% of dry weight and mainly comprise two types, glycosaminoglycans and fucoidans, with natural molecular weight ranges of 40,000–50,000 and 80,000–100,000, respectively [

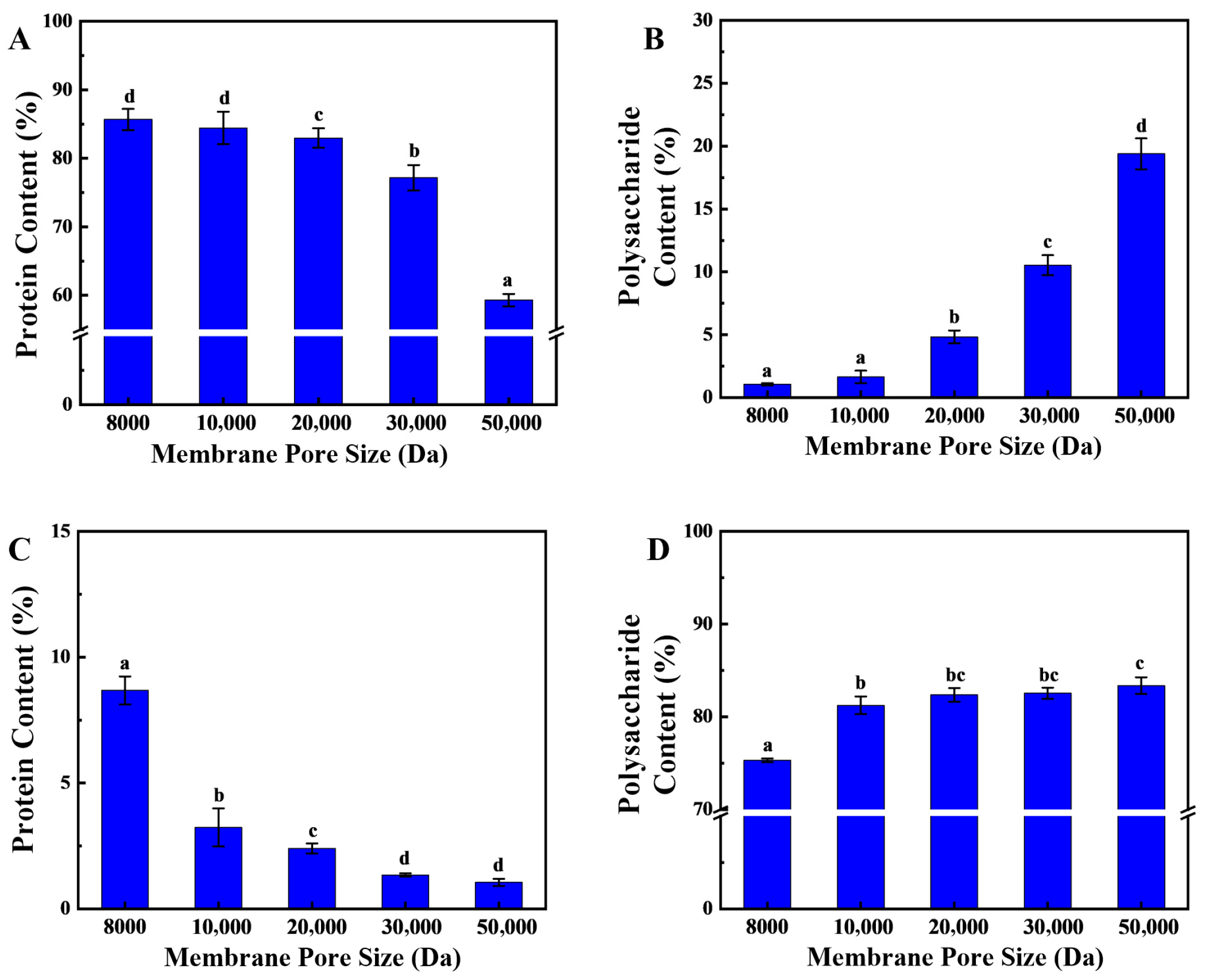

23]. The substantial molecular weight difference between these two components after enzymatic hydrolysis enables their simultaneous separation via membrane filtration. In the membrane separation processes, as the pore size of the ultrafiltration membrane increases, the peptide content in the effluent first stabilizes above 85% and then gradually decreases to 62% (

Figure 2A). The primary rationale for this phenomenon pertains to the molecular characteristics of the peptides resulting from secondary enzymatic hydrolysis, which characteristically exhibit smaller molecular weights. In contrast, sea cucumber polysaccharides, which have not undergone enzymatic hydrolysis, possess larger molecular weights and are retained by the ultrafiltration membrane. The results (

Figure 2B) indicate that when the ultrafiltration membrane’s pore size exceeds 20,000 Da, there is a significant increase in the polysaccharide content of the effluent. At this juncture, sea cucumber polysaccharides traverse the larger pores, engendering a substantial augmentation in polysaccharide content in the effluent, concomitant with a diminution in peptide proportion.

Furthermore, the findings indicate that as the pore size of the ultrafiltration membrane increases from 8000 Da to 10,000 Da, the protein content in the retained fraction rapidly decreases from 7.8% to less than 3% and continues to decrease as the pore size is further increased (

Figure 2C). This phenomenon can be attributed to the reduction in molecular weight of proteins with molecular weights above 10,000 Da following two-stage enzymatic hydrolysis. In comparison to polysaccharides, proteins exhibit a comparatively lower molecular weight, which results in the observed outcome. However, even as the pore size continues to increase, there is always 1.0% of protein-like substances in the retained fraction. These may be ultra-high-molecular-weight proteins or glycoprotein complexes that do not degrade easily. It has been demonstrated that when the ultrafiltration membrane’s pore size exceeds 10,000 Da, the polysaccharide content in the retained solution remains stable, exhibiting a significant difference from the retained solution produced by an 8000 Da ultrafiltration membrane (

Figure 2D). This finding suggests that the molecular weight of the protein in the retained fraction primarily ranges between 8000 and 10,000 Da.

In summary, an ultrafiltration membrane with a pore size of 10,000 Da was selected for the one-step separation of sea cucumber polysaccharides and peptides. After ultrafiltration, the effluent was sea cucumber peptides, with a protein content of 84.43 ± 0.96%, while the retained fraction was sea cucumber polysaccharides, with a polysaccharide content of 82.23 ± 1.26%. Previous studies have often used ion exchange resins to separate and purify sea cucumber polysaccharides, which results in high costs and reduced recovery rates of target active substances. In this study, following hydrolyzing sea cucumber body wall proteins, membrane separation technology was employed to simultaneously isolate polysaccharides and peptides. This approach reduced recovery costs while maintaining the efficiency of target product recovery.

2.3. Improvement of the Process for Removing Aromatic Amino Acids from HFO of Sea Cucumber

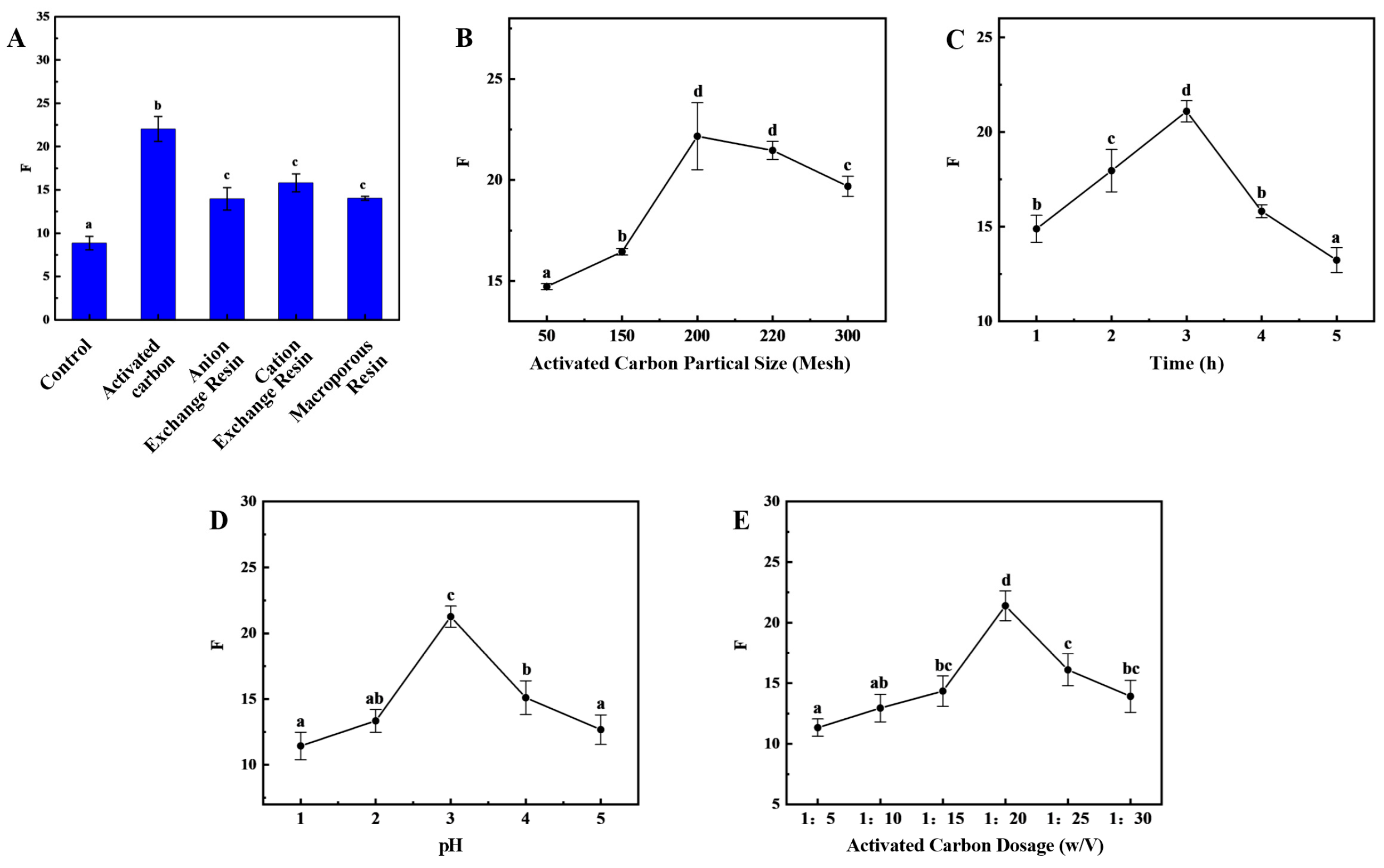

Presently, the predominant approach for preparing HFO from protein hydrolysate mixtures involves the reduction in aromatic amino acids. This method is also applicable to sea cucumber collagen peptides. The results demonstrated that the adsorption efficiency exhibited variability among the various adsorbents (

Figure 3A). The activated carbon demonstrated the most effective adsorption performance of the four adsorbents, exhibiting an OD220/OD280 ratio of 22.03 ± 1.43.

The impact of different grades of activated carbon on adsorption efficiency is significant. Among the tested grades, 200-mesh activated carbon demonstrated the optimal adsorption performance, exhibiting an OD220/OD280 ratio of 22.17 ± 1.66 (

Figure 3B). During the initial stage of de-aromatization, as time progresses, there is an increase in the contact between the activated carbon surface and aromatic compounds. This, in turn, enhances the adsorption capacity of the activated carbon surface and significantly improves de-aromatization efficiency. As time progresses, the content of aromatic amino acids diminishes, concurrent with the onset of adsorption of branched-chain amino acids. This phenomenon results in a decrease in OD220/OD280. When the adsorption time reaches 3 h, OD220/OD280 reaches its maximum value of 21.09 ± 0.56 (

Figure 3C). Conversely, an increase in pH results in an initial rise and subsequent decrease in the OD220/OD280 ratio (

Figure 3D). At a pH of 3, the maximum OD220/OD280 ratio is 21.26 ± 0.80, a result primarily attributable to the surface characteristics of activated carbon, the nature of the adsorbate, and the chemical environment of the solution. The surface of activated carbon contains various functional groups, and the charge state of the activated carbon surface changes with pH. At lower pH values, the surface typically carries a positive charge, which may enhance the adsorption of negatively charged aromatic compounds. Conversely, at higher pH values, the surface carries a negative charge, which may enhance the adsorption of positively charged molecules. In the presence of an acidic environment, the adsorption of certain aromatic compounds, which are inherently difficult to ionize, may be enhanced. The pH of the medium exerts a discernible influence on the solubility of these compounds, with concomitant alterations in solubility potentially exerting a direct effect on the available adsorption capacity of the aromatic compounds. The incorporation of activated carbon has been demonstrated to augment the number of adsorption sites, thereby enhancing the capacity for the adsorption of aromatic compounds and the subsequent de-aromatization process. However, it should be noted that there is an optimal addition amount. Exceeding this value may result in a gradual decrease in de-aromatization efficiency or even reduced adsorption efficiency. This can be attributed to factors such as mutual interference between activated carbon particles and uneven distribution. Furthermore, the presence of excessive activated carbon has been shown to result in increased treatment costs and the potential for processing complications. The OD220/OD280 ratio demonstrates a substantial response to varying levels of activated carbon addition, exhibiting an initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease with increasing addition levels. At an activated carbon addition ratio of 1:20, the OD220/OD280 ratio reaches its maximum value of 21.40 ± 1.23 (

Figure 3E).

A subsequent analysis of the amino acid composition both before and after activated carbon adsorption revealed a significant reduction in aromatic amino acids (

Supplementary Table S1). This finding suggests that activated carbon is highly effective in removing aromatic groups. Subsequent to activated carbon adsorption, the F-value of the amino acid composition exhibited a substantial increase, with the F-value attaining 23.82 after adsorption, thereby satisfying the criteria for HFO (F-value > 20). Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) are a class of amino acids that have been identified as being particularly important for athletes and fitness enthusiasts. Among these BCAAs, leucine, isoleucine, and valine have been found to promote muscle synthesis, aid in muscle repair and growth, and are of particular importance in these contexts. Furthermore, BCAAs have been demonstrated to reduce fatigue during exercise, enhance endurance, and improve athletic performance. These substances have also been demonstrated to alleviate muscle soreness and accelerate recovery. The yield of HFO from sea cucumbers was measured to be 24.56% through validated testing. The amino acid residue sequence analysis results for HFO are shown in

Supplementary Table S2.

2.6. The Anti-Fatigue Mechanism of HFO in Sea Cucumbers

Intense physical exertion results in a substantial increase in muscle demand for oxygen. However, as the body’s oxygen supply is incapable of meeting the demands of muscle consumption, it is compelled to activate anaerobic metabolic pathways. This results in a swift escalation in glycolysis rates and the subsequent accumulation of substantial quantities of lactic acid [

26]. The generation of substantial quantities of lactic acid results in a decrease in the pH level of blood within muscle tissue. This acidic environment has been demonstrated to exert a deleterious effect on cardiac circulatory function and skeletal muscle contraction capacity. Moreover, it has been identified as a pivotal factor contributing to exercise-induced fatigue [

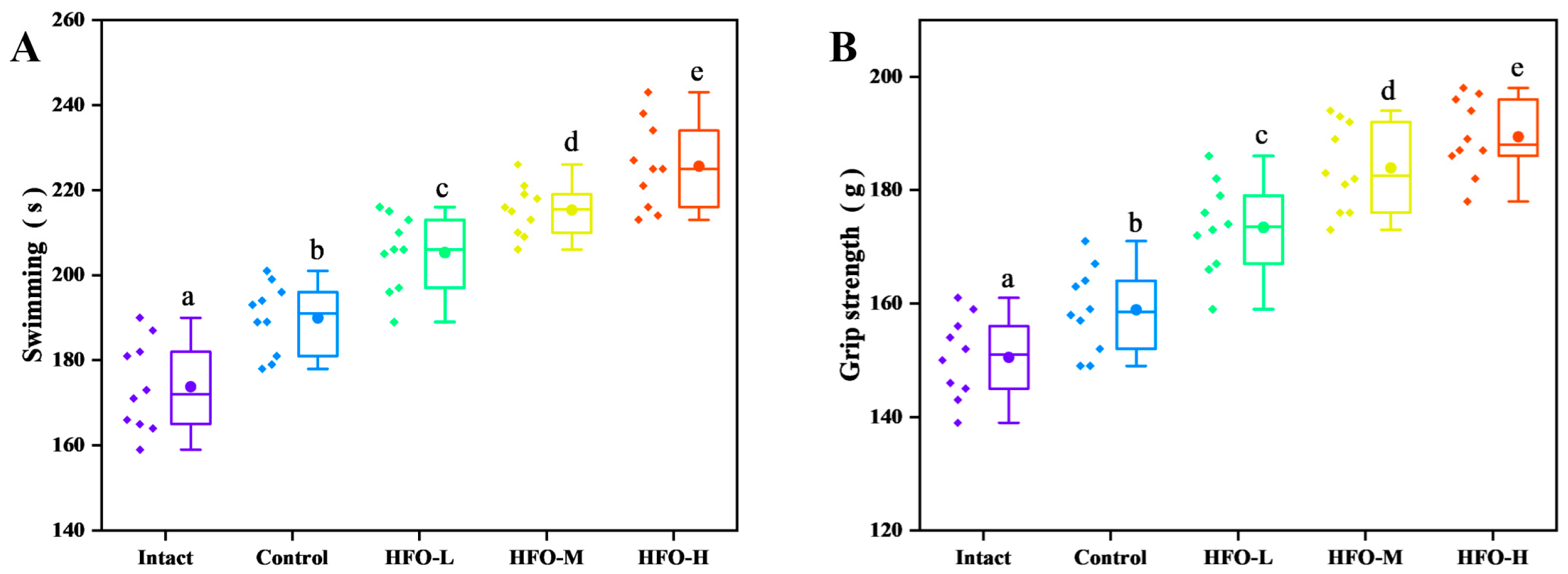

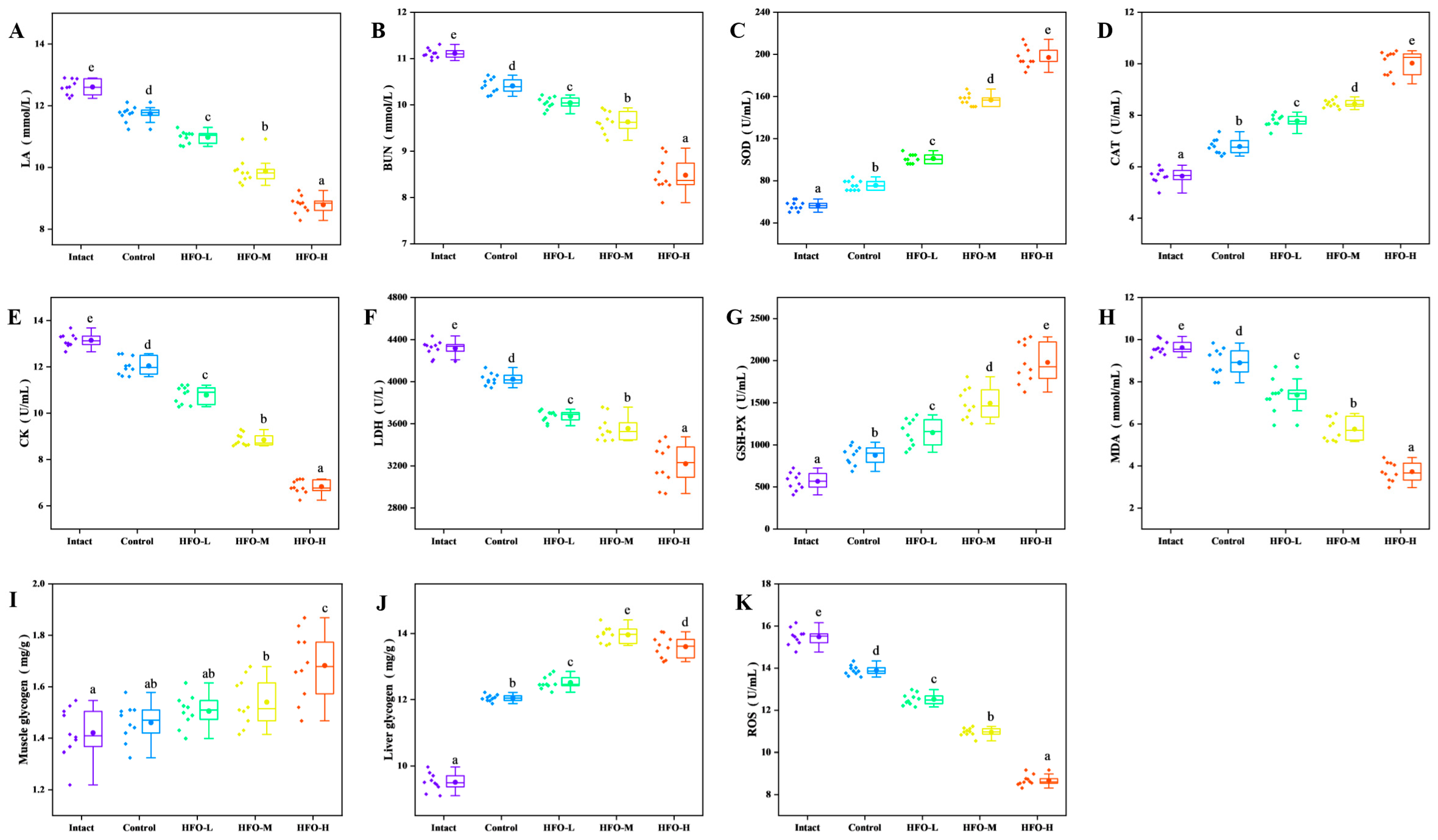

27]. As demonstrated in the results (

Figure 6A), following exhaustive swimming, the lactic acid levels in the HFO group were significantly lower than those in the control group. The reduction in lactic acid levels exhibited a dose-dependent relationship. Furthermore, during periods of strenuous physical activity, if the body experiences a deficiency in glucose supplementation for an extended duration, it will begin to break down proteins to maintain essential bodily functions. Urea, the final product of protein metabolism, accumulates in significant quantities within the body during prolonged endurance exercise. Given the established negative correlation between urea nitrogen levels and exercise endurance, it can be concluded that an improvement in exercise tolerance is associated with reduced urea nitrogen levels. Consequently, the reduction in urea nitrogen levels in the body is of paramount importance for enhancing fatigue resistance [

28]. The findings indicated a decline in urea nitrogen levels across all three groups (HFO low, medium, and high doses), with reductions of 9.63%, 13.32%, and 23.67%, respectively (

Figure 6B). The high-dose group demonstrated optimal outcomes, exhibiting a discernible dose-dependent effect.

Creatine kinase, an essential enzyme in energy metabolism, plays a pivotal role in the body’s energy management. This enzyme catalyzes the process of phosphorylation of creatine, resulting in the formation of high-energy phosphocreatine. A notable function of phosphocreatine is the transfer of a phosphate group to adenosine diphosphate (ADP), resulting in the formation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). This process is crucial for sustaining various bodily functions. During periods of physical exertion, the body experiences a significant demand for ATP, leading to its rapid consumption. In order to replenish sufficient ATP and sustain prolonged physical activity, the activity of creatine kinase—the enzyme regulating ATP production—increases, thereby generating more ATP and maintaining bodily functions, as well as delaying fatigue [

29]. During periods of strenuous physical activity, muscle cells are subject to damage, which results in an elevated level of permeability within the cell membrane. Consequently, creatine kinase from muscle cells can be released into the bloodstream, resulting in an increase in serum creatine kinase activity. Serum creatine kinase, a product of muscle cells, is a crucial indicator of muscle cell damage, with higher levels directly reflecting the extent of injury [

30]. As demonstrated in

Figure 6E, the serum creatine kinase activities in the HFO low-, medium-, and high-dose groups were lower than that in the blank group and the control group (sea cucumber small-molecule peptides). In comparison with the blank group, serum creatine kinase activity in the HFO low-, medium-, and high-dose groups exhibited decreases of 17.94%, 32.77%, and 48.14%, respectively. This phenomenon also demonstrates a certain degree of dose-dependent relationship. The findings suggest that HFO derived from sea cucumbers can effectively protect muscle cells and prevent the leakage of creatine kinase from muscle cells into the bloodstream. Furthermore, HFO have been shown to augment ATP levels in the body while concurrently protecting muscle cells. This protective effect contributes to the attainment of an anti-fatigue effect.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a pivotal enzyme in the reversible conversion of lactate to pyruvate, a process that occurs during anaerobic glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. It has been demonstrated that, particularly during periods of strenuous physical exertion, the activity of this enzyme is paramount for the efficient metabolism of lactate [

31]. The tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) is a series of reactions in which pyruvate is converted into carbon dioxide (CO

2) and water (H

2O). These byproducts are subsequently excreted from the body, thereby reducing the burden on the body caused by excessive lactate accumulation. During periods of strenuous physical activity, the permeability of muscle cell membranes increases, resulting in the leakage of lactate dehydrogenase into the bloodstream. This, in turn, leads to an increase in the activity of lactate dehydrogenase in the serum. This phenomenon is attributed to the reduction in energy derived from lactate metabolism within muscle cells, resulting in excessive lactate accumulation and, consequently, fatigue in the body [

32]. As illustrated in

Figure 6F, in comparison with the blank group and the control group administered low-dose sea cucumber oligopeptides, the serum lactate dehydrogenase activity in the high-dose sea cucumber oligopeptide group was notably diminished, manifesting a dose-dependent relationship. In comparison with the blank group, the HFO low-, medium-, and high-dose groups exhibited reductions of 14.94%, 17.67%, and 25.43%, respectively. These reductions were found to be statistically significant and exhibited a certain degree of dose dependency. The findings suggest that HFO can effectively protect muscle cells and mitigate the damage caused by intense exercise.

Glycogen is considered to be one of the primary forms of energy storage in the body. Glycogen provides the body with energy through five mechanisms [

33]: Firstly, during periods of intense physical exertion, a decline in blood glucose levels prompts the initiation of the hepatic glycogenolysis pathway. The process of glycolysis, initiated by the action of specific enzymes, involves the breakdown of liver glycogen into glucose, which is then released into the bloodstream. This process is crucial for maintaining blood glucose homeostasis and meeting the energy demands of cells during periods of physical exertion. During strenuous exercise or when oxygen supply is limited, muscle tissue can undergo a process of direct oxidation of glycogen for energy production through anaerobic respiration. This process, however, results in the production of lactic acid. The glycolytic pathway, which is predominantly located in the cytoplasm, plays a pivotal role in supporting various bodily functions. In the process of enzymatic catalysis, the transformation of glucose-1-phosphate into glucose-6-phosphate is initiated, thereby facilitating the entry of the glycolytic pathway and the subsequent production of a substantial amount of ATP. This process supplies energy to cells. The citric acid cycle, a series of biochemical reactions, occurs within cellular mitochondria, generating ATP as a byproduct. The pentose phosphate pathway, which plays a pivotal role in various metabolic reactions in vital organs such as the liver, breasts, and red blood cells, is another significant pathway. The significance of glycogen content in endurance exercise has been substantiated, underscoring the notion that the depletion of muscle glycogen plays a pivotal role in the onset of fatigue. Consequently, the glycogen content of a subject can serve as a significant indicator of their fatigue resistance. It has been demonstrated that an elevated level of glycogen within the body corresponds to an augmented degree of tolerance to physical exertion. As demonstrated in

Figure 6I, the muscle glycogen content in the HFO low-, medium-, and high-dose groups exceeded that of the control group, thereby indicating that HFO promote glycogen accumulation in the body, with the high-dose group exhibiting the optimal effect. In comparison with the control group, the muscle glycogen content in the HFO low-, medium-, and high-dose groups exhibited increases of 5.63%, 8.45%, and 18.31%, respectively, in relation to the control group. These increases were found to be statistically significant. The medium-dose and high-dose groups exhibited significant differences in comparison with the control group. As illustrated in

Figure 6J, the muscle glycogen content in the low, medium, and high-dose groups of HFO was higher than that in the control group. In comparison with the control group, the liver glycogen content in the low, medium, and high-dose groups of HFO increased by 31.57%, 46.94%, and 43.15%, respectively, as compared with the control group. The medium-dose group exhibited the most favorable outcomes. A comparison of the three HFO dose groups (low, medium, and high) with the control group revealed significant differences. In summary, the provision of oligopeptides with a high F-value to sea cucumbers has been demonstrated to elicit a marked increase in muscle and liver glycogen levels in murine subjects. This phenomenon is accompanied by an enhancement in energy metabolism, culminating in an augmented exercise tolerance capacity of the organism.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is a significant antioxidant enzyme that is present in living organisms. It has the capacity to eliminate free radicals. SOD catalyzes the conversion of superoxide anion radicals into H

2O

2 and O

2, thereby protecting cells from oxidative damage [

34]. Catalase, a component of the body’s natural defense system, has been shown to effectively eliminate reactive oxygen species, thus preventing oxidative damage induced by physical exertion. Catalase enzymes, present in the body, facilitate the decomposition of H

2O

2 into H

2O and O

2, thereby reducing the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide within cells and preventing damage to cellular structure and function [

35]. Glutathione peroxidase, an important antioxidant enzyme in the body, plays a crucial role in maintaining redox homeostasis. Glutathione peroxidase catalyzes the reaction between reduced glutathione and peroxides, thereby eliminating peroxides in the body. This process helps alleviate oxidative stress-induced damage to cells and protects cellular health [

36]. Consequently, the augmentation of antioxidant enzyme activity contributes to the mitigation of damage incurred by exercise-induced oxidative stress reactions to cells, thereby facilitating the alleviation of fatigue [

37]. As shown in

Figure 6C, the SOD activity in the HFO low, medium, and high-dose groups exhibited a significant increase compared to the blank group and the sea cucumber small-molecule peptide group. Additionally, a dose-dependent relationship was observed within a specific range. In comparison with the blank group, the SOD activity in the HFO low, medium, and high-dose groups exhibited increases of 1.79, 2.77, and 3.49 times, respectively, with significant differences, as demonstrated in

Figure 6D, the three groups of HFO at low, medium, and high doses exhibited increased catalase activity compared to the blank group and sea cucumber small-molecule peptides. This increase in catalase activity showed a dose-dependent trend within a certain range. In comparison with the blank group, the catalase activity in the three groups of HFO at low, medium, and high doses increased by 38.01%, 49.91%, and 77.97%, respectively, indicating significant differences. As demonstrated in

Figure 6G, the three groups of HFO at low, medium, and high doses exhibited significantly elevated glutathione peroxidase activity in comparison to the blank group and the sea cucumber small-molecule peptide group. This activity demonstrated a dose-dependent trend within a specific range. In comparison with the blank group, the glutathione peroxidase activity in the HFO low, medium, and high-dose groups increased by 2.01-, 2.67-, and 3.52-fold, respectively, with significant differences.

As indicated by research findings and experimental results, periods of high-intensity physical exertion have been demonstrated to result in substantial fluctuations in the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within the human body. The increase in ROS has been demonstrated to exacerbate lipid peroxidation in liver and muscle tissues. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is a primary metabolic byproduct of lipid peroxidation in cell membranes. Consequently, the levels of MDA can serve as a reflection of the body’s antioxidant stress response, and alterations in MDA levels can also be utilized for the assessment of the extent of fatigue [

38]. As demonstrated in

Figure 6H, the content of MDA in the three groups that were administered HFO at low, medium, and high doses exhibited a significant decrease, with the most pronounced effect observed in the high-dose group. In comparison with the blank group, the MDA content in the three groups that were administered HFO at low, medium, and high doses exhibited a decrease of 1.29-, 1.67-, and 2.59-fold, respectively, in relation to the control group. These results were found to be statistically significant. As demonstrated by the preceding analysis, HFO derived from sea cucumbers have the capacity to augment the activity of antioxidant enzymes within the body, thereby leading to a reduction in reactive oxygen species. In addition, these peptides have been observed to inhibit lipid peroxidation in cell membranes, resulting in an anti-fatigue effect.

Some studies have demonstrated that reactive oxygen species (ROS), which include superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and their downstream byproducts such as peroxides and carboxylates, can induce protein oxidation in response to exercise, thereby contributing to muscle fatigue. Elevated levels of ROS within cells are also indicative of apoptosis. Under typical conditions, ROS are eliminated by the antioxidant system and maintained within a normal range. When there is an imbalance between oxidative and antioxidant processes, the body is unable to maintain a normal range of ROS, which can lead to oxidative stress. This, in turn, can result in damage to various macromolecules within the body [

37]. As demonstrated in

Figure 6, the levels of ROS in mice fed HFO at low, medium, and high doses exhibited a downward trend. This finding was concomitant with an increase in the activities of SOD, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase. The high-dose group fed HFO demonstrated the most optimal results, with a 43.99% reduction in reactive oxygen species in the body.