The Impact of New Human Resource Management Practices on Innovation Performance during the COVID 19 Crisis: A New Perception on Enhancing the Educational Sector

Abstract

:1. Introduction

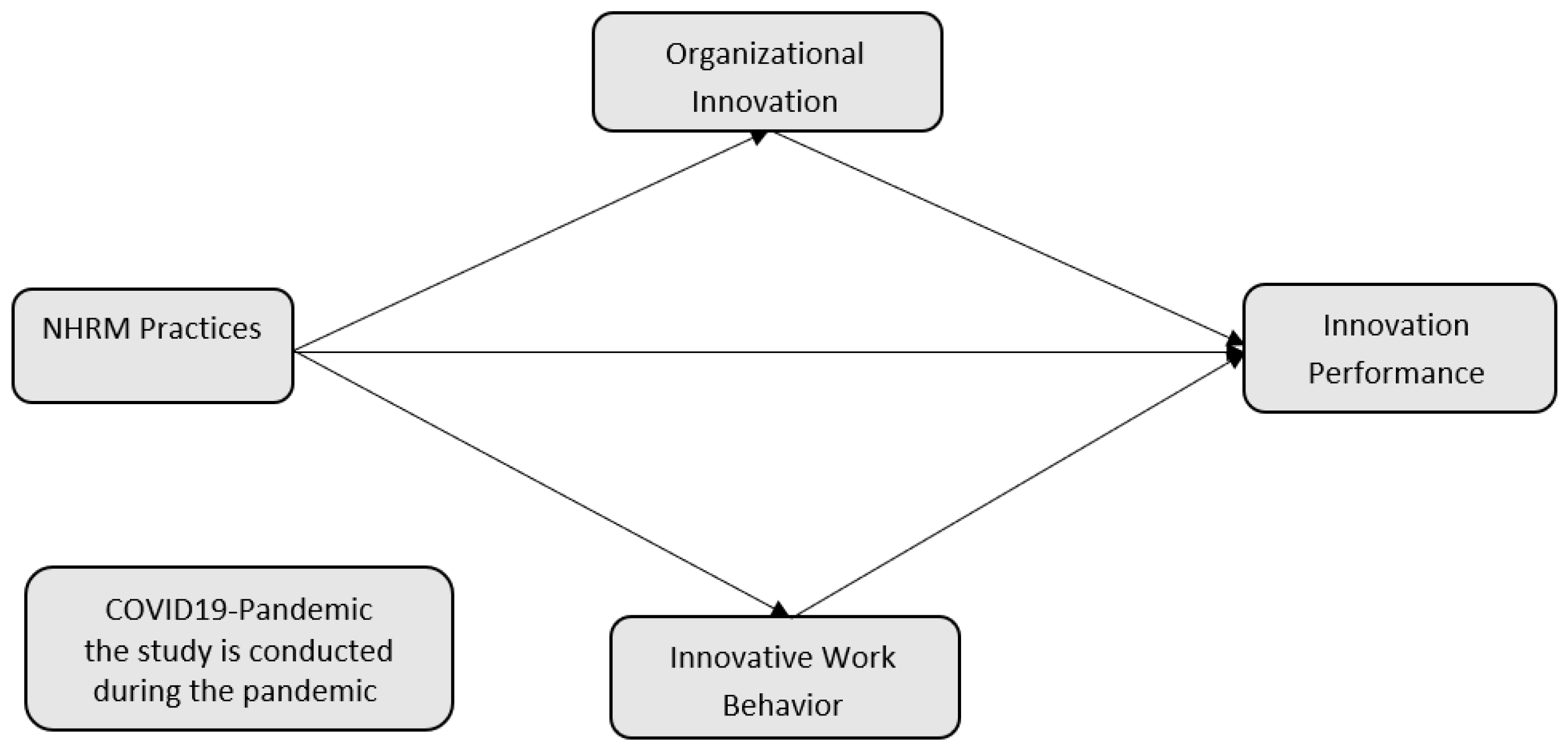

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. New Human Resource Management Practices

2.2. Organizational Innovation

2.3. Innovative Work Behavior

2.4. Innovation Performance

2.5. Human Resource Management Practices, Innovation Performance, Educational Sector, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.6. Organizational Innovation as a Mediator

2.7. Innovative Work Behavior as a Mediator

3. Methods

3.1. Design of Research, Instrument, Sample Technique, and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Scales

4. Data Analysis and Results

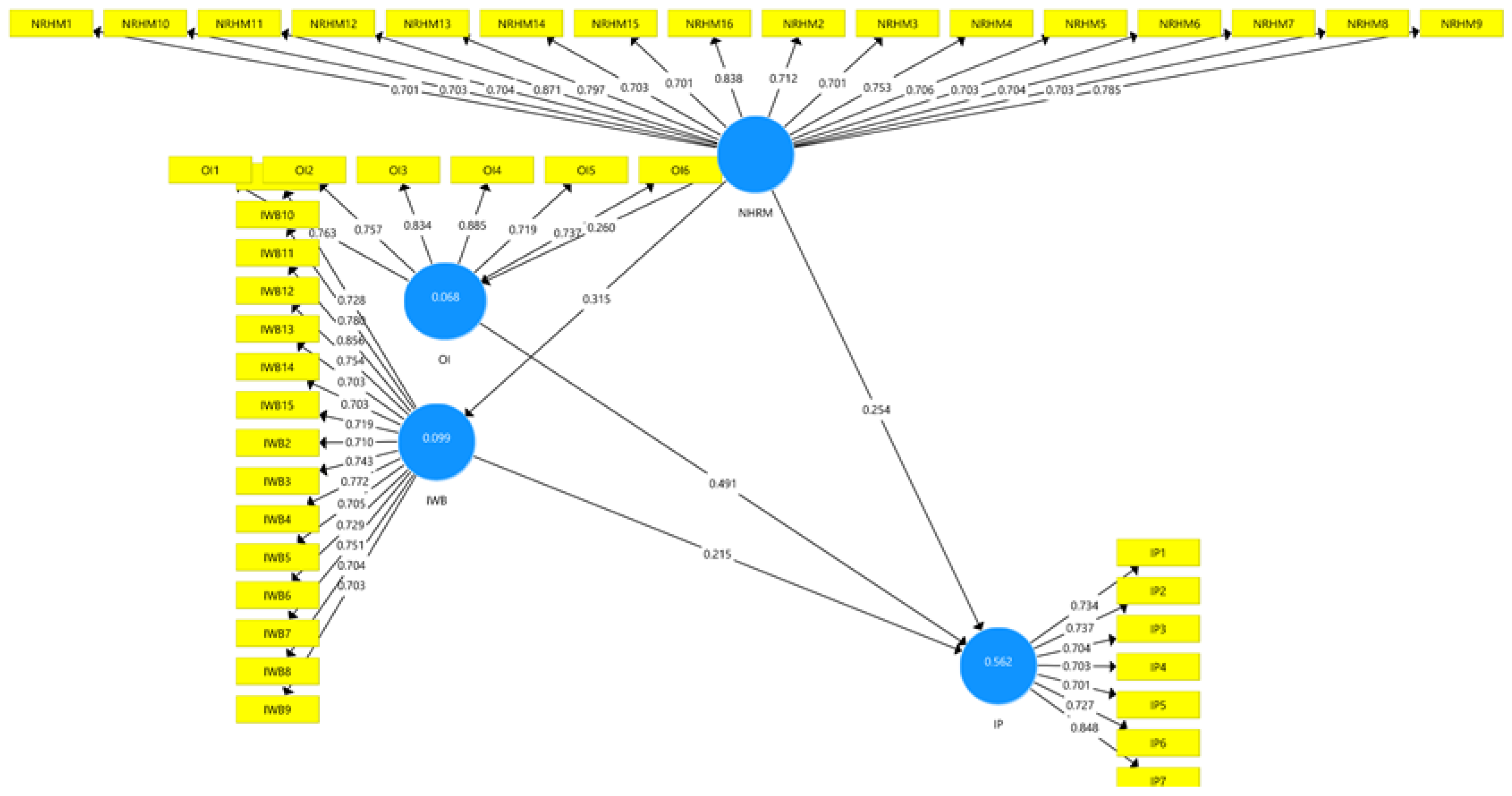

4.1. Assessing the Formative Measurement Model

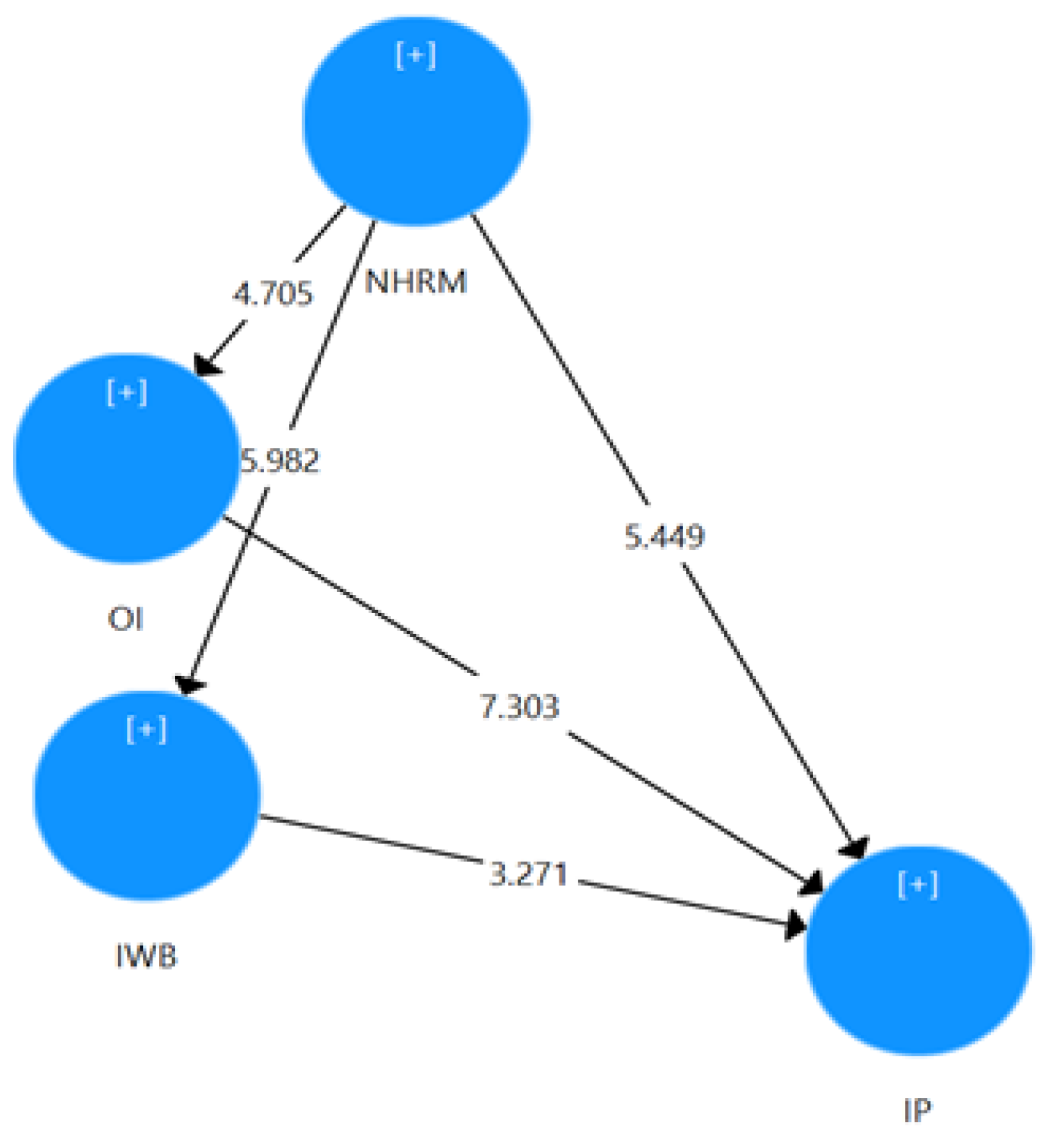

4.2. Assessing the Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Waheed, A.; Miao, X.; Waheed, S.; Ahmad, N.; Majeed, A. How new HRM practices, organizational innovation, and innovative climate affect the innovation performance in the IT industry: A moderated-mediation analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waheed, A.; Xiaoming, M.; Ahmad, N.; Waheed, S. Moderating effect of information technology ambidexterity linking new human resource management practices and innovation performance. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 19, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Apaydin, M. A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1154–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Nehles, A.; Renkema, M.; Janssen, M. HRM and innovative work behaviour: A systematic literature review. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 1228–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Waheed, S.; Karamat, J.; Ahmad, N.; Majeed, A. Implementation and Adoption of E-HRM in Small and Medium Enterprises of Pakistan. In Information Technology and Intelligent Transportation Systems; IOS Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; pp. 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, F.M.; Chuang, S.H. Corporate social responsibility. iBusiness 2014, 6, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alsoud, A.R.; Harasis, A.A. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Student’s E-Learning Experience in Jordan. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1404–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebersberger, B.; Kuckertz, A. Hop to it! The impact of organization type on innovation response time to the COVID-19 crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boris, P.; Lin, J.Y. (Eds.) Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics 2008, Regional: Higher Education and Development; The World Bank: Cape Town, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, K.; Bajwa, S.U.; Ansted, R.B.; Mamoon, D. Evaluating human resource management capacity for effective implementation of advanced metering infrastructure by electricity distribution companies in Pakistan. Util. Policy 2016, 41, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, H.O.; Ojiabo, O.U.; Emecheta, B.C. Integrating TAM, TPB and TOE frameworks and expanding their characteristic constructs for e-commerce adoption by SMEs. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2015, 6, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venkatesh, V. Determinants of perceived ease of use: Integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2000, 11, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Odoardi, C.; Battistelli, A.; Montani, F. Can goal theories explain innovative work behaviour? The motivating power of innovation-related goals. Appl. Psychol. Bull. (Boll. Psicol. Applicata) 2010, 261–262, 3–17. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262205727 (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Waheed, A.; Xiaoming, M.; Karamat, J.; Waheed, S. Comparison of Human Resource Planning and Job Analysis process in banking sector of Pakistan. In 2016 Joint International Information Technology, Mechanical and Electronic Engineering Conference; Atlantis Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuler, R.S.; Jackson, S.E. Linking competitive strategies with human resource management practices. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1987, 1, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miranda Castro, M.V.; de Araújo, M.L.; Ribeiro, A.M.; Demo, G.; Meneses, P.P.M. Implementation of strategic human resource management practices: A review of the national scientific production and new research paths. Rev. Gestão 2020, 27, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, G.D.; Pini, P. New HRM practices and exploitative innovation: A shopfloor level analysis. Ind. Innov. 2011, 18, 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, S.; Reichstein, T. Transition to entrepreneurship from the public sector: Predispositional and contextual effects. Manag. Sci. 2009, 55, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Miao, X.; Ahmad, N.; Waheed, S.; Majeed, A. New HRM Practices and Innovation Performance; The Moderating Role of Information Technology Ambidexterity. In Information Technology and Intelligent Transportation Systems; IOS Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; pp. 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harazneh, Y.M.; Sila, I. The Impact of E-HRM Usage on HRM Effectiveness: Highlighting the Roles of Top Management Support, HR Professionals, and Line Managers. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. JGIM 2021, 29, 118–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedumaran, G.; Rani, C. A study on impact of E-HRM activities in the companies growth. ZENITH Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2021, 11, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nutsubidze, N.; Schmidt, D.A. Rethinking the role of HRM during COVID-19 pandemic era: Case of Kuwait. Rev. Socio-Econ. Perspect. 2021, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, D.; Miozzo, M. New human resource management practices in knowledge-intensive business services firms: The case of outsourcing with staff transfer. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 1521–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moohammad, A.Y.; Nor’Aini, Y.; Kamal, E.M. Influences of firm size, age and sector on innovation behaviour of construc-tion consultancy services organizations in developing countries. Bus. Manag. Dyn. 2014, 4, 01–09. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, J.K.; Indradewa, R.; Syah, T.Y.R. The leadership styles impact, in learning organizations, and organizational innovation towards organizational performance over manufacturing companies, Indonesia. J. Multidiscip. Acad. 2020, 4, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Demo, G.; Costa, A.C.R.; Coura, K.V.; Miyasaki, A.C.; Fogaça, N. What do scientific research say about the effectiveness of human resource management practices? Current itineraries and new possibilities. Rev. Adm. Unimep 2020, 18, 138–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dorenbosch, L.; Engen, M.L.V.; Verhagen, M. On-the-job innovation: The impact of job design and human resource man-agement through production ownership. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2005, 14, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Innovative behaviour and job involvement at the price of conflict and less satisfactory relations with co-workers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 76, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleysen, R.F.; Street, C.T.; Street, C.T. Toward a multi-dimensional measure of individual innovative behavior. J. Intellect. Cap. 2001, 2, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J.P.; Den Hartog, D.N. Innovative work behavior: Measurement and validation. EIM Bus. Policy Res. 2008, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Döngül, E.S.; Uygun, S.V.; Öztürk, M.B.; Huy, D.T.N.; Tuan, P.V. Exploring the Relationship between Abusive Management, Self-Efficacy and Organizational Performance in the Context of Human–Machine Interaction Technology and Artificial Intelligence with the Effect of Ergonomics. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornhill, S. Knowledge, innovation and firm performance in high-and low-technology regimes. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundvall, B.A. Higher education, innovation and economic development. High. Educ. Dev. 2008, 8, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christa, U.; Kristinae, V. The effect of product innovation on business performance during COVID 19 pandemic. Uncertain Supply Chain. Manag. 2021, 9, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbules, N.C.; Fan, G.; Repp, P. Five trends of education and technology in a sustainable future. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebell, D.; O’Dwyer, L.M.; Russell, M.; Hoffmann, T. Concerns, considerations, and new ideas for data collection and re-search in educational technology studies. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2010, 43, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterick, M.; Charlwood, A. HRM and the COVID-19 pandemic: How can we stop making a bad situation worse? Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterova, K. Accelerated Digitalization Process as a Response of Hrm to the COVID-19 Crisis in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: The Case of latvia. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Green Thinking, Riga, Latvia, 21–22 April 2021; p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, K.; Foss, N.J. New human resource management practices, complementarities and the impact on innovation per-formance. Camb. J. Econ. 2003, 27, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guderian, C.C.; Bican, P.M.; Riar, F.J.; Chattopadhyay, S. Innovation management in crisis: Patent analytics as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. R&D Manag. 2021, 51, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitasari, D.; Yuwono, T.; Cahyono, Y.; Asbari, M.; Sajudin, M.; Radita, F.R.; Asnaini, S.W. Effect of Hard Skills, Soft Skills, Organizational Learning and Innovation Capability on Indonesian Teachers’ Performance during COVID-19 Pandemic. Solid State Technol. 2020, 63, 2927–2952. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and the entrepreneurship education community. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2020, 14, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hyari, H.S.A. The Effect of Applying Education Technology Innovation Trends on Learning Outcomes from Management Students’ Perspective in Al-Balqa Applied University, Salt-Jordan. In Proceedings of the Conference: 4th International Education and Values Symposium (ISOEVA)/ONLINE, Karabuk, Turkey, 24–26 December 2020; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348161676 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Tawalbeh, M. The policy and management of information technology in Jordanian schools. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2001, 32, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaafreh, S.J.A. A Case Study: How an E-Learning Education during COVID-19 Has Impacted Jordanian School Students. Available online: http://journals.mejsp.com/ar/research-single.php?reID=177&jID=9&vID=93&title= (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Menon, S. HRM in higher education: The need of the hour. IOSR J. Res. Method Educ. 2015, 5, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salman, S.; Haider, A.S. ; Haider, A.S. Jordanian university students’ views on emergency online learning during COVID-19. Online Learn. 2021, 25, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grencikova, A.; Safrankova, J.M.; Sikyr, M. Fundamental Human Resource Management Practices Aimed at Dealing with New Challenges in the Labour Market. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2020, 19, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Valle, R.; Jiménez-Jiménez, D. HRM and product innovation: Does innovative work behaviour mediate that relationship? Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1417–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E. Business Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Maymone, M.B.; Venkatesh, S.; Secemsky, E.; Reddy, K.; Vashi, N.A. Research techniques made simple: Web-based survey research in dermatology: Conduct and applications. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. Available online: http://lccn.loc.gov/2015051045 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Hamilton, J.D. Causes and consequences of the oil shock of 2007-08. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 2009, 40, 215–283. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w15002 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Nulty, D.D. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collier, J.E.; Bienstock, C.C. An analysis of how nonresponse error is assessed in academic marketing research. Mark. Theory 2007, 7, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinacore, J.M. Book Reviews: Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions: By Leona S. Aiken and Stephen G. West. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1991, 212 pp. Eval. Pract. 1993, 14, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E. Rethinking partial least squares path modeling: In praise of simple methods. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2152644 (accessed on 1 August 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: www.amazon.de/Partial-Squares-Structural-Equation-Modeling/dp/148337744X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1462617386&sr=8-1&keywords=PLS-sem#reader_148337744X (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rungtusanatham, M.; Miller, J.W.; Boyer, K.K. Theorizing, testing, and concluding for mediation in SCM research: Tutorial and procedural recommendations. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yus Kelana, B.W.; Abu Mansor, N.N.; Ayyub Hassan, M. Does Sustainability Practices of Human Resources as a New Approach Able to Increase the Workers Productivity in the SME Sector Through Human Resources Policy Support? Adv. Sci. Lett. 2015, 21, 1501–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prange, C.; Pinho, J.C. How personal and organizational drivers impact on SME international performance: The mediating role of organizational innovation. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, R.H.; Jaaffar, A.H. The mediating effect of crisis management on leadership styles and hotel performance in Jordan. Int. J. Financ. Res. 2020, 11, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures | Items | Frequency (n = 358) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 183 | 51.1 |

| Female | 175 | 48.9 | |

| Age | 20 to 29 | 5 | 1.4 |

| 30 to 40 | 102 | 28.5 | |

| 41 to 50 | 189 | 52.8 | |

| Above 50 | 62 | 17.3 | |

| Education | High school | 4 | 1.1 |

| Diploma | 18 | 5.0 | |

| Bachelor | 125 | 34.9 | |

| Post-Graduate | 211 | 58.9 | |

| Job Experience | 1 to 4 years | 10 | 2.8 |

| 5 years to 10 years | 45 | 12.6 | |

| 11 years to 15 years | 85 | 23.7 | |

| Above 15 years | 218 | 60.9 | |

| Job Title | Employee | 227 | 63.4 |

| Head of Department | 94 | 26.2 | |

| Director of Department | 16 | 4.5 | |

| Directorate Director | 21 | 5.9 |

| Construct | Item Code | Loadings | α | rho (pA) | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHRM Practices (Waheed et al.) [1]. | 0.951 | 0.952 | 0.95 | 0.545 | |||

| 1. | “Necessary actions are being taken by the HR department to avoid layoffs during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM1 | 0.701 | ||||

| 2. | “The HR department’s hiring procedure is more efficient due to the adoption of E-recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic.” | NHRM2 | 0.712 | ||||

| 3. | “Adoption of an E-HRM portal to maintain the employee’s record and information during COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM3 | 0.701 | ||||

| 4. | “The HR department is reorganizing employees to appropriate positions effectively as per situations during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM4 | 0.753 | ||||

| 5. | “The effort which I put in my job is fairly rewarded during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM5 | 0.706 | ||||

| 6. | “One’s contribution recognition reflects the fairness of the reward system during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM6 | 0.703 | ||||

| 7. | “Individual performance-based reward system during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM7 | 0.704 | ||||

| 8. | “The Ministry allows me to make decisions regarding my job during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM8 | 0.703 | ||||

| 9. | “Individual are allowed to make decisions in the absence of top-level [management] in the immediate work situation during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM9 | 0.785 | ||||

| 10. | “The HR department keeps employees informed about the work issues as well as its performance during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM10 | 0.703 | ||||

| 11. | “I feel that I am part of the team during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM11 | 0.704 | ||||

| 12. | “Team members have the ability to solve problems during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM12 | 0.871 | ||||

| 13. | “Team members support the innovation process during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM13 | 0.797 | ||||

| 14. | “Appropriate job training for employees is set by the Ministry during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM14 | 0.703 | ||||

| 15. | “The Ministry encourages employees to extend their abilities during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM15 | 0.701 | ||||

| 16. | “Training of new skills and technology to compete in the learning industry [is provided] during the COVID-19 pandemic” | NHRM16 | 0.838 | ||||

| Organizational Innovation (Waheed et al.) [1] | 0.905 | 0.909 | 0.905 | 0.615 | |||

| 17. | “The Ministry often tries new ideas during COVID-19 pandemic” | OI1 | 0.763 | ||||

| 18. | “The Ministry often tries out new trends to perform tasks during the COVID-19 pandemic” | OI2 | 0.757 | ||||

| 19. | “The Ministry is innovative in its operations during the COVID-19 pandemic” | OI3 | 0.834 | ||||

| 20. | “The Ministry frequently introduces new products and services during the COVID-19 pandemic” | OI4 | 0.885 | ||||

| 21. | “Innovation level in our ministry is risky and resisted during the COVID-19 pandemic” | OI5 | 0.719 | ||||

| 22. | “Since one year ago introduction of new services has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic” | OI6 | 0.737 | ||||

| Innovative Work Behavior Dorenbosch et al. [27] | 0.947 | 0.948 | 0.947 | 0.545 | |||

| 23. | “To what extent do you actively think concerning improvements in the work of direct colleagues during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB1 | 0.728 | ||||

| 24. | “To what extent do you generate ideas to improve or renew services your department provides during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB2 | 0.710 | ||||

| 25. | “To what extent do you generate ideas on how to optimize knowledge and skills within your department during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB3 | 0.743 | ||||

| 26. | “To what extent do you generate new solutions to old problems during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB4 | 0.772 | ||||

| 27. | “To what extent do you discuss matters with direct colleagues concerning your/their work during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB5 | 0.705 | ||||

| 28. | “To what extent do you suggest new ways of communicating within your department during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB6 | 0.729 | ||||

| 29. | “To what extent do you try to detect impediments to collaboration and coordination during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB7 | 0.751 | ||||

| 30. | “To what extent do you actively engage in gathering information to identify deviations within your department during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB8 | 0.704 | ||||

| 31. | “To what extent do you, in collaboration with colleagues, get to transform new ideas in a way that they become applicable in practice during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB9 | 0.703 | ||||

| 32. | “To what extent do you realize ideas within your department/ministry with an amount of persistence during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB10 | 0.780 | ||||

| 33. | “To what extent do you make your supervisor enthusiastic for your ideas during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB11 | 0.856 | ||||

| 34. | “To what extent do you identify new ways to use computer technology more effectively in your work during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB12 | 0.754 | ||||

| 35. | “To what extent do you independently identify and deploy new computer applications into your work situations during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB13 | 0.703 | ||||

| 36. | “To what extent do you seek new possibilities to gain financial means or to reduce costs during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB14 | 0.703 | ||||

| 37. | “To what extent do you keep yourself informed about your department’s financial situation during the COVID-19 pandemic?” | IWB15 | 0.719 | ||||

| Innovation Performance (Waheed et al.) [1] | 0.893 | 0.895 | 0.893 | 0.544 | |||

| 38. | “Quality of products and services during the COVID-19 pandemic” | IP1 | 0.734 | ||||

| 39. | “Development of products and services during the COVID-19 pandemic” | IP2 | 0.737 | ||||

| 40. | “Evaluation of the ministry subjectively during the COVID-19 pandemic” | IP3 | 0.704 | ||||

| 41. | “Ability to retain and attract employees during the COVID-19 pandemic” | IP4 | 0.703 | ||||

| 42. | “The general relationship between employees and management during the COVID-19 pandemic” | IP5 | 0.701 | ||||

| 43. | “The motivation for creativity/flexibility of employeef during the COVID-19 pandemic” | IP6 | 0.727 | ||||

| 44. | “Innovative ideas during the COVID-19 pandemic | IP7 | 0.848 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Innovation Performance | ||||

| 2. Innovative Work Behavior | 0.549 | |||

| 3. NHRM Practices | 0.449 | 0.313 | ||

| 4. Organizational Innovation | 0.667 | 0.520 | 0.259 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Innovation Performance | 0.738 | |||

| 2. Innovative Work Behavior | 0.552 | 0.738 | ||

| 3. NHRM Practices | 0.450 | 0.315 | 0.738 | |

| 4. Organizational Innovation | 0.670 | 0.522 | 0.260 | 0.785 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IWB -> IP | 0.2155 | 0.2141 | 0.0659 | 3.2712 | 0.001 | |

| NHRM -> IP | 0.2536 | 0.2543 | 0.0466 | 5.4488 | 0 | |

| NHRM -> IWB | 0.315 | 0.3216 | 0.0527 | 5.9821 | 0 | |

| NHRM -> OI | 0.2605 | 0.2669 | 0.0554 | 4.7046 | 0 | |

| OI -> IP | 0.4915 | 0.4916 | 0.0673 | 7.3032 | 0 | |

| NHRM→OI→IP | 0.128 | 0.13 | 0.033 | 3.874 | 0.000 | |

| NHRM→IWB→IP | 0.068 | 0.069 | 0.025 | 2.708 | 0.007 | |

| Hypothesis | Parameters | β | SE | t-value | p-value | |

| H1 | Direct effects | |||||

| NHRM→IP | 0.253 | 0.046 | 5.448 | 0.000 | Significant | |

| NHRM→OI | 0.260 | 0.054 | 4.782 | 0.000 | Significant | |

| NHRM→IWB | 0.315 | 0.053 | 5.906 | 0.000 | Significant | |

| OI→IP | 0.491 | 0.068 | 7.192 | 0.000 | Significant | |

| IWB→IP | 0.215 | 0.066 | 3.244 | 0.000 | Significant | |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| H2 | NHRM→OI→IP | 0.128 | 0.032 | 3.958 | 0.000 | Significant |

| H3 | NHRM→IWB→IP | 0.068 | 0.025 | 2.708 | 0.007 | Significant |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kutieshat, R.; Farmanesh, P. The Impact of New Human Resource Management Practices on Innovation Performance during the COVID 19 Crisis: A New Perception on Enhancing the Educational Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052872

Kutieshat R, Farmanesh P. The Impact of New Human Resource Management Practices on Innovation Performance during the COVID 19 Crisis: A New Perception on Enhancing the Educational Sector. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052872

Chicago/Turabian StyleKutieshat, Ruba, and Panteha Farmanesh. 2022. "The Impact of New Human Resource Management Practices on Innovation Performance during the COVID 19 Crisis: A New Perception on Enhancing the Educational Sector" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052872