Circulating miR-122-5p, miR-125b-5p, and miR-27a-3p in Post-Mortem Whole Blood: An Exploratory Study of the Association with Sepsis-Related Death

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Selection and Sample Collection

2.2. RNA Isolation and miRNA Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Sample

3.2. miRNA Expression and Association Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.2. Forensic and Diagnostic Implications

4.3. Study Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cDNA | Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid |

| Ct | Cycle threshold |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| PMI | Post-mortem Interval |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Rudd, K.E.; Johnson, S.C.; Agesa, K.M.; Shackelford, K.A.; Tsoi, D.; Kievlan, D.R.; Colombara, D.V.; Ikuta, K.S.; Kissoon, N.; Finfer, S.; et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 395, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomara, C.; Riezzo, I.; Bello, S.; De Carlo, D.; Neri, M.; Turillazzi, E. A Pathophysiological Insight into Sepsis and Its Correlation with Postmortem Diagnosis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 4062829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passaro, G.; Dell’aquila, M.; De Filippis, A.; Baronti, A.; Costantino, A.; Iannaccone, F.; De Matteis, A. Post-mortem diagnosis of sepsis: When it’s too late. LA Clin. Ter. 2021, 171, e60–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiese, A.; Scatena, A.; Costantino, A.; Chiti, E.; Occhipinti, C.; La Russa, R.; Di Paolo, M.; Turillazzi, E.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Expression of MicroRNAs in Sepsis-Related Organ Dysfunction: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasques-Nóvoa, F.; Quina-Rodrigues, C.; Cerqueira, R.; Baganha, F.; Marques, M.I.; Leite-Moreira, A.F.; Roncon-Albuquerque, R. Abstract 20517: MicroRNA-155: A New Player in Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction. Circulation 2014, 130, A20517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, P.; Skarp, S.; Saukko, T.; Säkkinen, H.; Syrjälä, H.; Kerkelä, R.; Saarimäki, S.; Bläuer, S.; Porvari, K.; Pakanen, L.; et al. Postmortem analyses of myocardial microRNA expression in sepsis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindayna, K. MicroRNA as Sepsis Biomarkers: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Ma, K.; Zhang, H.; He, M.; Zhang, P.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, N.; Ma, D.; Chen, L. A Time Course Study Demonstrating m RNA, micro RNA, 18 S r RNA, and U 6 sn RNA Changes to Estimate PMI in Deceased Rat’s Spleen. J. Forensic 2014, 59, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mao, J.; Li, Y.; Luo, H.; Wu, J.; Liao, M.; Liang, W.; Zhang, L. 5 miRNA expression analyze in post-mortem interval (PMI) within 48 h. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. Suppl. Ser. 2013, 4, e190–e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, D.; Cui, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, X.; Li, Y. Correlation of microRNA-125a/b with acute respiratory distress syndrome risk and prognosis in sepsis patients. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2020, 34, e23098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. MiR-125b but not miR-125a is upregulated and exhibits a trend to correlate with enhanced disease severity, inflammation, and increased mortality in sepsis patients. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2020, 34, e23094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmel, T.; Schäfer, S.T.; Frey, U.H.; Adamzik, M.; Peters, J. Increased circulating microRNA-122 is a biomarker for discrimination and risk stratification in patients defined by sepsis-3 criteria. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; An, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Shen, Y.; Cai, W.; Zhu, W. Oxidative stress-related circulating miRNA-27a is a potential biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis in patients with sepsis. BMC Immunol. 2022, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Androulidaki, A.; Iliopoulos, D.; Arranz, A.; Doxaki, C.; Schworer, S.; Zacharioudaki, V.; Margioris, A.N.; Tsichlis, P.N.; Tsatsanis, C. The Kinase Akt1 Controls Macrophage Response to Lipopolysaccharide by Regulating MicroRNAs. Immunity 2009, 31, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisti, F.; Wang, S.; Brandt, S.L.; Glosson-Byers, N.; Mayo, L.D.; Son, Y.M.; Sturgeon, S.; Filgueiras, L.; Jancar, S.; Wong, H.; et al. Nuclear PTEN enhances the maturation of a microRNA regulon to limit MyD88-dependent susceptibility to sepsis. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, eaai9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.A.; So, A.Y.-L.; Sinha, N.; Gibson, W.S.J.; Taganov, K.D.; O’connell, R.M.; Baltimore, D. MicroRNA-125b Potentiates Macrophage Activation. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 5062–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roderburg, C.; Luedde, M.; Cardenas, D.V.; Vucur, M.; Scholten, D.; Frey, N.; Koch, A.; Trautwein, C.; Tacke, F.; Luedde, T. Circulating microRNA-150 serum levels predict survival in patients with critical illness and sepsis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebicka, J.; Anadol, E.; Elfimova, N.; Strack, I.; Roggendorf, M.; Viazov, S.; Wedemeyer, I.; Drebber, U.; Rockstroh, J.; Sauerbruch, T.; et al. Hepatic and serum levels of miR-122 after chronic HCV-induced fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 2013, 58, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, A.J.; Guo, C.; Cook, J.A.; Wolf, B.; Halushka, P.V.; Fan, H. Plasma levels of microRNA are altered with the development of shock in human sepsis: An observational study. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.; Liu, B.; He, H.; Gu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhu, D.; Cang, J.; Luo, Z. MicroRNA-27a alleviates LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice via inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis through modulating TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 2001–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caserta, S.; Kern, F.; Cohen, J.; Drage, S.; Newbury, S.F.; Llewelyn, M.J. Circulating Plasma microRNAs can differentiate Human Sepsis and Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, S.; Hübner, M.; Strauß, G.; Effinger, D.; Bauer, M.; Weis, S.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Kreth, S. Identification of suitable controls for miRNA quantification in T-cells and whole blood cells in sepsis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-L.; Nie, Z.-Q.; Lu, Y.; Yang, X.; Song, C.; Chen, H.; Zhu, S.; Chen, B.-B.; Huang, J.; Geng, S.; et al. Circulating miR-125b but not miR-125a correlates with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the expressions of inflammatory cytokines. Medicine 2017, 96, e9059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.-M.; Lin, K.-Y.; Chen, Y.-Q. Diverse functions of miR-125 family in different cell contexts. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, Z.; Rasheed, N.; Al Abdulmonem, W.; Khan, M.I. MicroRNA-125b-5p regulates IL-1β induced inflammatory genes via targeting TRAF6-mediated MAPKs and NF-κB signaling in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Sci. Rep. Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14729. 2019, 9, 6882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Li, S.; Cui, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, X.; Li, Y. Plasma miR-125a and miR-125b in sepsis: Correlation with disease risk, inflammation, severity, and prognosis. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2020, 34, e23036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Ma, X.; Li, T.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Zhou, J.; Meng, Y.; et al. Serum Exosomes miR-122-5P Induces Hepatic and Renal Injury in Septic Rats by Regulating TAK1/SIRT1 Pathway. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, B.; Deng, J.; Jin, Y.; Xie, L. Serum miR-122 correlates with short-term mortality in sepsis patients. Crit. Care 2014, 18, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, K.; Tong, Z. MicroRNA-122-5p regulates coagulation and inflammation through MASP1 and HO-1 genes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2022, 100, 105268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ruan, Z.; Mao, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, N.; Jiang, L. miR-27a is up regulated and promotes inflammatory response in sepsis. Cell. Immunol. 2014, 290, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, R.; Xu, Q.; Zheng, G.; Qiu, G.; Ge, M.; Shu, Q.; Xu, J. Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Derived Extracellular Vesicles Alleviate Acute Lung Injury Via Transfer of miR-27a-3p*. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, e599–e610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stassi, C.; Mondello, C.; Baldino, G.; Spagnolo, E.V. Post-Mortem Investigations for the Diagnosis of Sepsis: A Review of Literature. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sepsis (N = 26) | Controls (N = 19) | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 70 (65, 83) | 60 (52, 77) | 0.118 |

| Days since death, median (IQR) | 4 (2, 7) | 3 (3, 4) | 0.564 |

| Sex, males, N (%) | 14 (54) | 16 (84) | 0.054 |

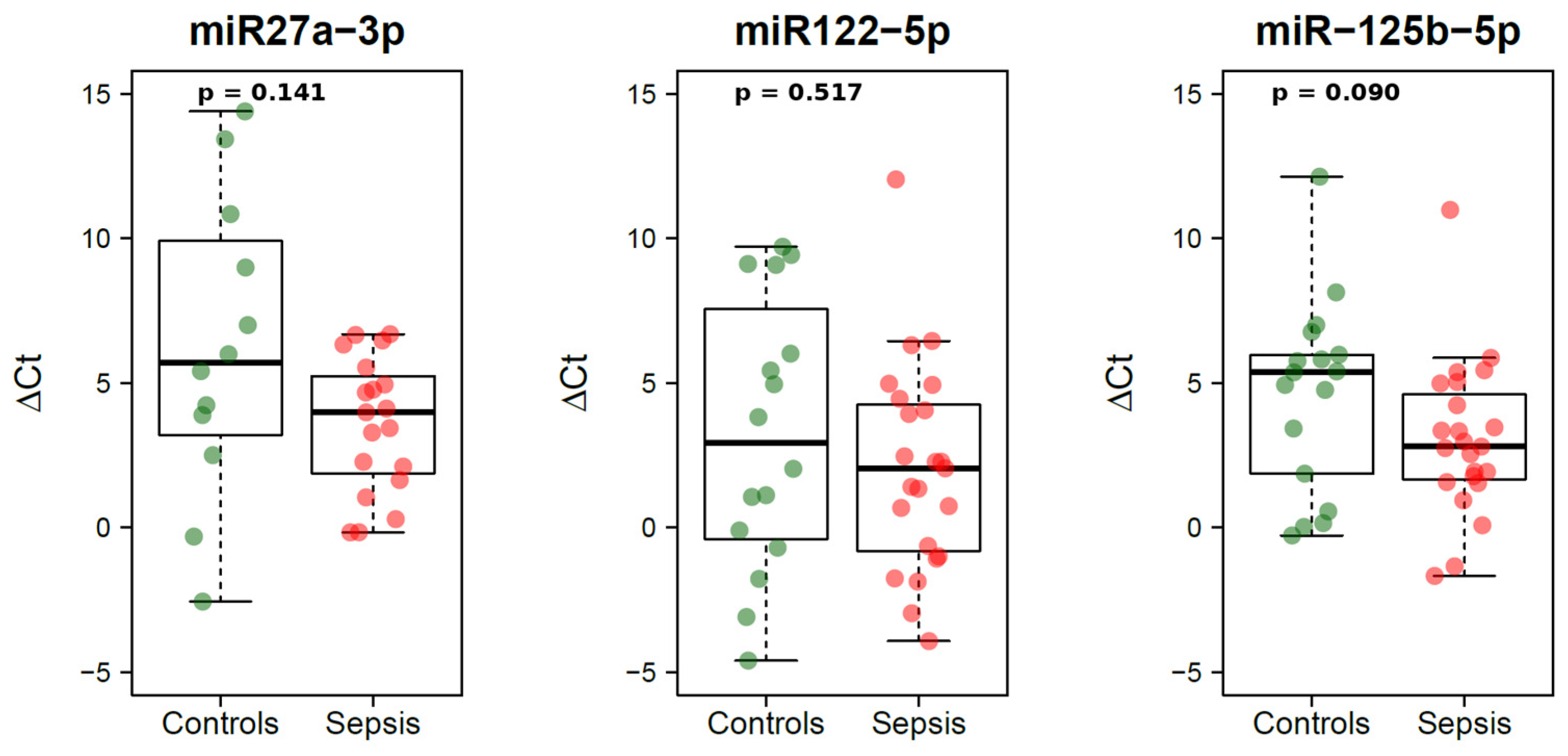

| miRNA-27a-3p, ΔCt, median (IQR) | 4.0 (1.9, 5.2) | 5.7 (3.5, 9.5) | 0.141 |

| miRNA-122-5p, ΔCt, median (IQR) | 2.0 (−0.8, 4.3) | 2.9 (−0.3, 6.8) | 0.517 |

| miRNA-125b-5p, ΔCt, median (IQR) | 2.8 (1.7, 4.6) | 5.4 (1.9, 6.0) | 0.090 |

| Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p-Value | BH-Adjusted p-Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-Value | BH-Adjusted p-Value | |

| MiRNA-27a-3p | −3.6 (−7.4, 0.2) | 0.061 | 0.091 | −5.1 (−9.5, −0.6) | 0.027 | 0.041 |

| MiRNA-122-5p | −2.3 (−5.2, 0.6) | 0.116 | 0.116 | −2.3 (−5.9, 1.2) | 0.191 | 0.191 |

| MiRNA-125b-5p | −2.5 (−4.6, −0.5) | 0.016 | 0.048 | −3.4 (−5.7, −1.1) | 0.005 | 0.016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Occhipinti, C.; Scatena, A.; Turillazzi, E.; Bonuccelli, D.; Pricoco, P.; Fornili, M.; Maiese, A.; Taddei, S.; Di Paolo, M.; Rocchi, A. Circulating miR-122-5p, miR-125b-5p, and miR-27a-3p in Post-Mortem Whole Blood: An Exploratory Study of the Association with Sepsis-Related Death. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010049

Occhipinti C, Scatena A, Turillazzi E, Bonuccelli D, Pricoco P, Fornili M, Maiese A, Taddei S, Di Paolo M, Rocchi A. Circulating miR-122-5p, miR-125b-5p, and miR-27a-3p in Post-Mortem Whole Blood: An Exploratory Study of the Association with Sepsis-Related Death. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleOcchipinti, Carla, Andrea Scatena, Emanuela Turillazzi, Diana Bonuccelli, Paolo Pricoco, Marco Fornili, Aniello Maiese, Stefano Taddei, Marco Di Paolo, and Anna Rocchi. 2026. "Circulating miR-122-5p, miR-125b-5p, and miR-27a-3p in Post-Mortem Whole Blood: An Exploratory Study of the Association with Sepsis-Related Death" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010049

APA StyleOcchipinti, C., Scatena, A., Turillazzi, E., Bonuccelli, D., Pricoco, P., Fornili, M., Maiese, A., Taddei, S., Di Paolo, M., & Rocchi, A. (2026). Circulating miR-122-5p, miR-125b-5p, and miR-27a-3p in Post-Mortem Whole Blood: An Exploratory Study of the Association with Sepsis-Related Death. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010049