Targeting the Ubiquitin–Proteasome System in Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanistic Insights and Translational Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

Literature Search and Review Approach

2. Composition and Roles of the UPS in the Heart

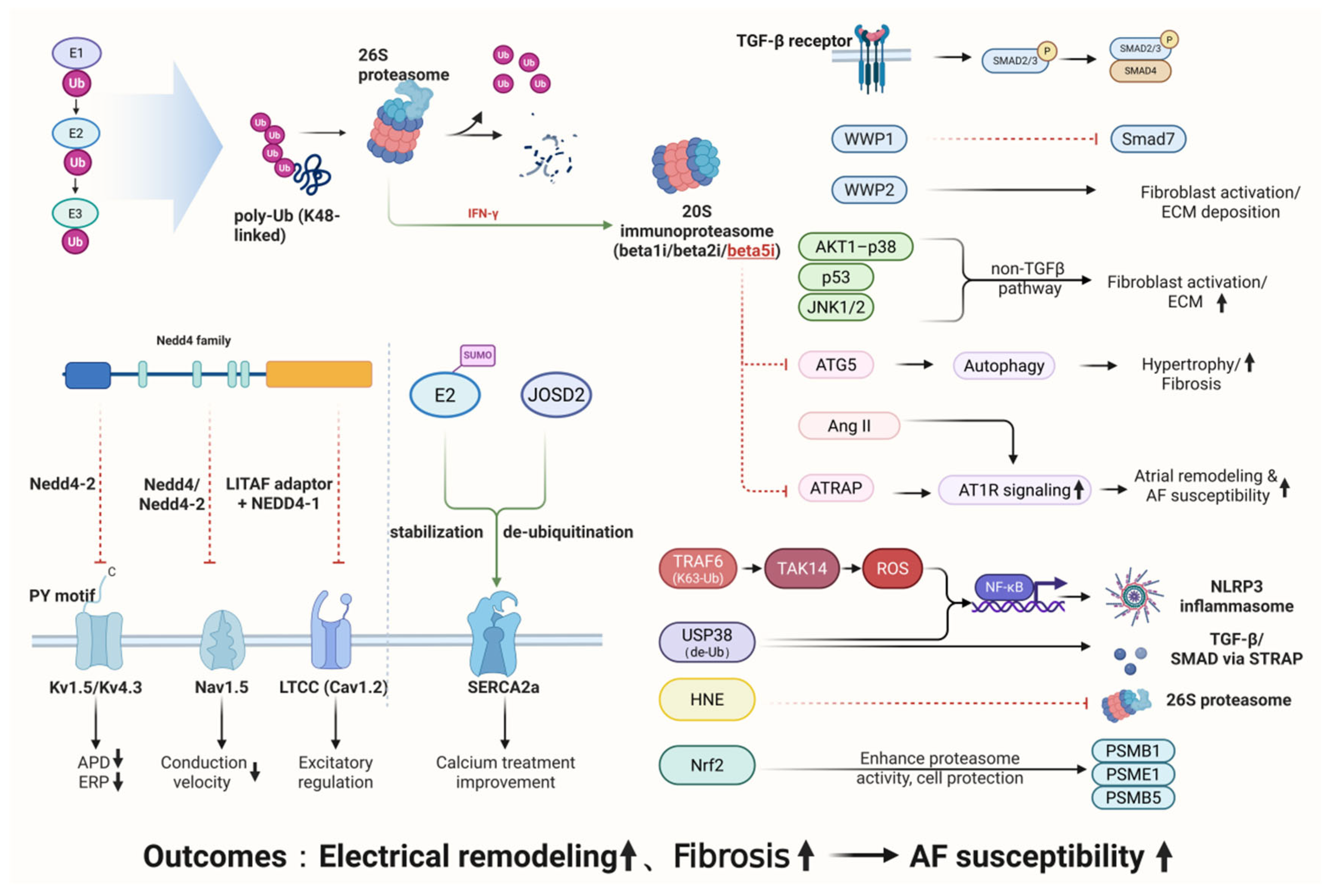

3. Molecular Links Between UPS Dysregulation and AF Pathogenesis

3.1. Mechanisms of UPS in Atrial Electrical Remodeling

3.1.1. Ubiquitination and Degradation of Potassium Channel Proteins

3.1.2. Regulation of Sodium Channel Proteins

3.1.3. UPS-Dependent Dysregulation of Calcium-Handling Proteins

3.2. Mechanisms of UPS in Structural Remodeling of Atrial Fibrillation

3.2.1. Roles of the UPS in AF

- (1)

- TGF-β/Smad-Dependent Pathway

- (2)

- Non-TGF-β Pathways

- (3)

- Stress and Inflammatory Regulation

- (4)

- Emerging Regulatory Factors

3.2.2. Deubiquitinases in the Regulation of Atrial Fibrillation

3.2.3. Role of the Immunoproteasome in Atrial Fibrillation

3.2.4. UPS-Mediated Inflammatory and Oxidative-Stress Pathways in Atrial Fibrillation

| Regulatory Component | Target Protein/Pathway | Functional Effect (↑ Activation/↓ Inhibition) | Associated Pathological Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEDD4-2 | Kv1.5/Nav1.5/L-type calcium channel | Shortened action potential duration (↑)/Reduced conduction velocity (↑) | Electrical remodeling |

| MuRF1 | Myofibrillar proteins | Enhanced atrial structural remodeling (↑) | Structural remodeling |

| WWP1/2 | TGFβ/Smad | Activation of fibroblast-mediated fibrosis (↑) | Structural remodeling–Fibrosis |

| β5i (Immunoproteasome subunit) | ATRAP/ATG5 | Fibrosis and inflammation amplification (↑) | Structural remodeling–Inflammatory stress |

| USP38 (DUB) | STRAP/TGFβ | Fibrosis and electrical uncoupling (↑) | Structural + Electrical remodeling |

| JOSD2 (DUB) | SERCA2a | Improved calcium handling (↓ Hypertrophy) | Structural remodeling–Hypertrophy (putative) |

4. Targeting the UPS for Therapeutic Intervention in Atrial Fibrillation

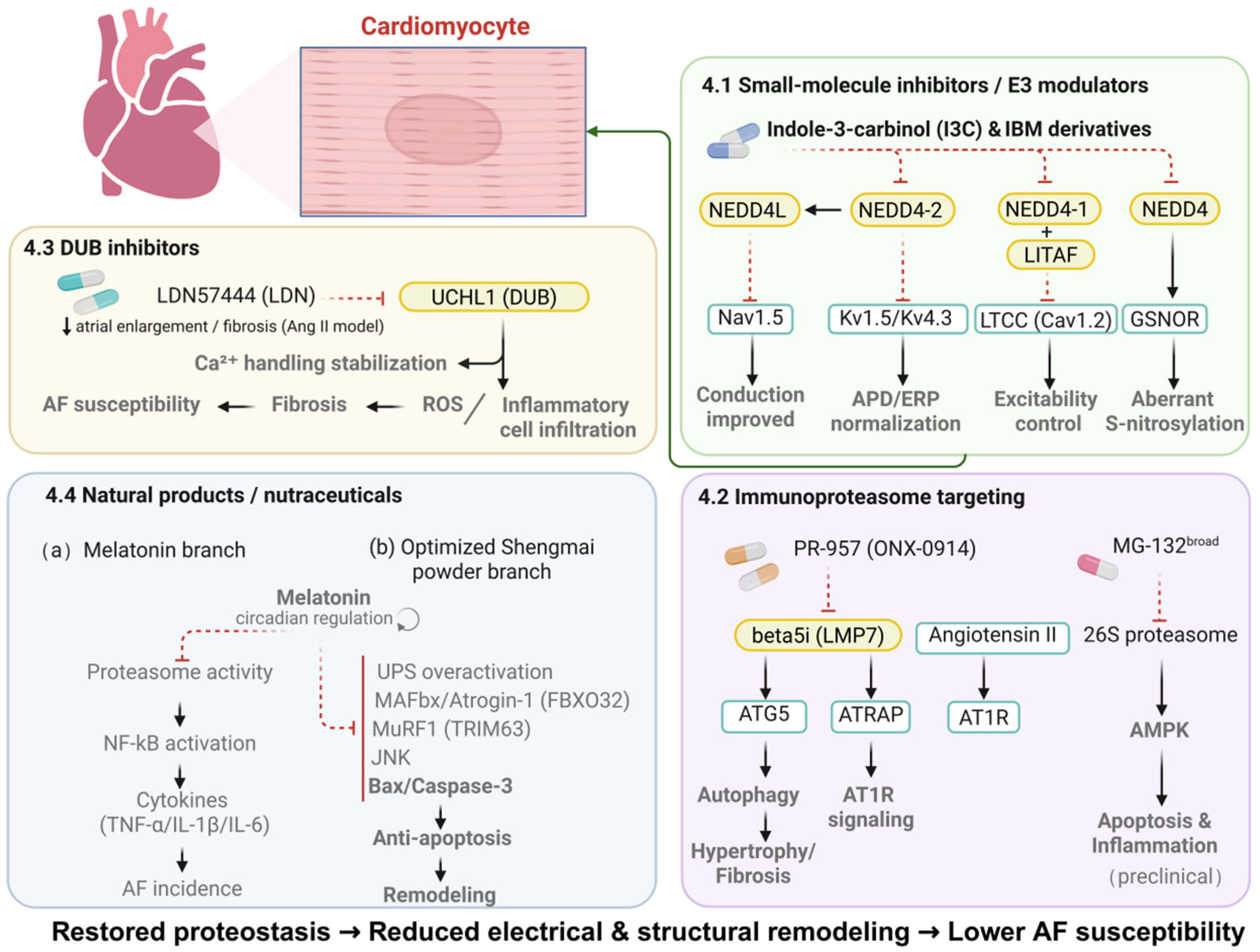

4.1. Small-Molecule Inhibitors and E3 Ligase Modulators: Restoring Ion Channel Stability and Electrical Remodeling

4.2. Immunoproteasome-Specific Targeting: Attenuating the Inflammation–Fibrosis Axis

4.3. Deubiquitinase Inhibitors: Modulating Calcium Handling and AF Susceptibility

4.4. Natural Compounds and Nutritional Interventions: Supporting UPS Homeostasis and AF Prevention

| Target Category | Representative Agent | Mechanism of Action | Research Stage | Main Effect (↑ Promotes/↓ Inhibits) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3 ligase inhibitor | IBM/I3C | Inhibits NEDD4-mediated degradation of GSNOR | degradation of GSNOR Phase II clinical trial | ↓ Cardiac hypertrophy; improves electrical remodeling |

| DUB inhibitor | UCHL1 inhibitor LDN57444 (LDN) | Suppresses Ang II–induced fibrosis, inflammation, and ROS production | Animal model study | ↓ Atrial fibrosis and inflammation |

| DUB | USP38 | Stabilizes STRAP and activates TGF-β/Smad fibrotic signaling | Animal model (CKD-AF) | ↑ Fibrosis and electrical uncoupling |

| Immunoproteasome inhibitor | PR-957 | Selectively inhibits β5i subunit, reducing oxidative stress and fibrosis | Preclinical (AF model) | ↓ Atrial remodeling and inflammation |

| Natural compound | Optimized Shengmai Powder | Suppresses excessive UPS activation; downregulates MAFbx and MuRF1 expression | Basic → Clinical translation | ↓ Fibrosis; improves cardiac remodeling |

4.5. Translational Challenges and Limitations of UPS-Targeted Therapies

4.6. Mechanistic Versus Potentially Translatable UPS Targets in Atrial Fibrillation

5. Future Perspectives

- (1)

- Selectivity and Safety of UPS Targets

- (2)

- Lack of AF-Specific Animal Models and Translational Studies

- (3)

- Complexity of the UPS Regulatory Network and the Challenge of Individualized Therapy

- (4)

- Future Research Directions

- (5)

- Integration of UPS-Targeted Strategies into Current AF Management

6. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| UPS | Ubiquitin–proteasome system |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-κB |

| USP38 | Ubiquitin-specific protease 38 |

| SERCA2a | Sarcoplasmic/Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a |

| NEDD4-1 | Neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 4-1 |

| NEDD4-2 | Neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 4-2 |

| WWP1 | WW domain-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase 1 |

| WWP2 | WW domain-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase 2 |

| TRAF6 | TNF receptor-associated factor 6 |

| JOSD2 | Josephin domain–containing protein 2 |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain–containing 3 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| ATRAP | Angiotensin II type-1 receptor–associated protein |

| STRAP | Serine/threonine kinase receptor-associated protein |

| ATG5 | Autophagy-related protein 5 |

| DUBs | Deubiquitinases |

| GSNOR | S-nitrosoglutathione reductase |

| I3C | Indole-3-carbinol |

| LITAF | LPS-induced TNF factor |

| UCHL1 | Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 |

References

- Brundel, B.J.J.M.; Ai, X.; Hills, M.T.; Kuipers, M.F.; Lip, G.Y.H.; de Groot, N.M.S. Atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, A.L.; Frankel, D.S.; Kim, D.H.; Ko, D.; Kramer, D.B.; Lydston, M.; Fang, M.C.; Shah, S.J. Management of atrial fibrillation in older adults. BMJ 2024, 386, e076246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornej, J.; Börschel, C.S.; Benjamin, E.J.; Schnabel, R.B. Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation in the 21st Century. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Caprara, A.L.F. Impact of Age on the Outcomes of Atrial Fibrillation-Related Stroke. Heart Mind 2024, 8, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, S.; Kaneko, H.; Okada, A.; Morita, K.; Itoh, H.; Michihata, N.; Jo, T.; Takeda, N.; Morita, H.; Fujiu, K.; et al. Age Modified Relationship Between Modifiable Risk Factors and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2022, 15, e010409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korantzopoulos, P.; Letsas, K.P.; Tse, G.; Fragakis, N.; Goudis, C.A.; Liu, T. Inflammation and atrial fibrillation: A comprehensive review. J. Arrhythmia 2018, 34, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasis, P.; Theofilis, P.; Vlachakis, P.K.; Korantzopoulos, P.; Patoulias, D.; Antoniadis, A.P.; Fragakis, N. Atrial Fibrosis in Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanistic Insights, Diagnostic Challenges, and Emerging Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattel, S.; Heijman, J.; Zhou, L.; Dobrev, D. Molecular Basis of Atrial Fibrillation Pathophysiology and Therapy. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X. The interplay between autophagy and the ubiquitin–proteasome system in cardiac proteotoxicity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2015, 1852, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Mizushima, T.; Saeki, Y. The proteasome: Molecular machinery and pathophysiological roles. Biol. Chem. 2012, 393, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Patrocinio, A.B.; Rodrigues, V.; Guidi Magalhães, L. P53: Stability from the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Specific 26S Proteasome Inhibitors. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 3836–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndsen, C.E.; Wolberger, C. New insights into ubiquitin E3 ligase mechanism. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amm, I.; Sommer, T.; Wolf, D.H. Protein quality control and elimination of protein waste: The role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, I.; Glickman, M.H. Proteasome in action: Substrate degradation by the 26S proteasome. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021, 49, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshal, K.S.; Roder, K.; Kabakov, A.Y.; Werdich, A.A.; Chiang, D.Y.-E.; Turan, N.N.; Xie, A.; Kim, T.Y.; Cooper, L.L.; Lu, Y.; et al. LITAF (Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Tumor Necrosis Factor) Regulates Cardiac L-Type Calcium Channels by Modulating NEDD (Neural Precursor Cell Expressed Developmentally Downregulated Protein) 4-1 Ubiquitin Ligase. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2019, 12, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minegishi, S.; Ishigami, T.; Kawamura, H.; Kino, T.; Chen, L.; Nakashima-Sasaki, R.; Doi, H.; Azushima, K.; Wakui, H.; Chiba, Y.; et al. An Isoform of Nedd4-2 Plays a Pivotal Role in Electrophysiological Cardiac Abnormalities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris-Moreno, D.; Taillandier, D.; Polge, C. MuRF1/TRIM63, Master Regulator of Muscle Mass. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, A.; Fung, G.; Luo, H. Immune and non-immune functions of the immunoproteasome. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2012, 17, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston-Carey, H.K.; Pomatto, L.C.; Davies, K.J. The Immunoproteasome in oxidative stress, aging, and disease. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 51, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Bi, H.-L.; Lai, S.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Li, N.; Cao, H.-J.; Han, L.; Wang, H.-X.; Li, H.-H. The immunoproteasome catalytic β5i subunit regulates cardiac hypertrophy by targeting the autophagy protein ATG5 for degradation. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau0495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Bai, J.; Lin, Q.-Y.; Liu, R.-S.; Yu, X.-H.; Li, H.-H. Immunoproteasome Subunit β5i Promotes Ang II (Angiotensin II)–Induced Atrial Fibrillation by Targeting ATRAP (Ang II Type I Receptor–Associated Protein) Degradation in Mice. Hypertension 2019, 73, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventopoulos, G.; Koros, R.; Travlos, C.; Perperis, A.; Chronopoulos, P.; Tsoni, E.; Koufou, E.-E.; Papageorgiou, A.; Apostolos, A.; Kaouris, P.; et al. Mechanisms of Atrial Fibrillation: How Our Knowledge Affects Clinical Practice. Life 2023, 13, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, E.; Sanguinetti, M.C.; Bartos, D.C.; Bers, D.M.; Chen-Izu, Y.; Chiamvimonvat, N.; Colecraft, H.M.; Delisle, B.P.; Heijman, J.; Navedo, M.F.; et al. Potassium channels in the heart: Structure, function and regulation. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 2209–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Guo, J.; Yang, T.; Li, W.; Zhang, S. Regulation of the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channel by Nedd4 family interacting proteins (Ndfips). Biochem. J. 2015, 472, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; Shallow, H.; Yang, T.; Li, W.; Xu, J.; Fridman, M.D.; Yang, X.; Zhang, S. Cell surface expression of human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) channels is regulated by caveolin-3 protein via the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 33132–33141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Perez, A.; Kumar, S.; Cook, D.I. GRK2 interacts with and phosphorylates Nedd4 and Nedd4-2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 359, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, K.; Carr, M.J. Voltage-gated sodium channels. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2015, 22, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchal, G.A.; Remme, C.A. Subcellular diversity of Nav1.5 in cardiomyocytes: Distinct functions, mechanisms and targets. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Shou, W. Cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 mutations and cardiac arrhythmia. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2012, 33, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bemmelen, M.X.; Rougier, J.-S.b.; Gavillet, B.; Apothéloz, F.; Daidié, D.; Tateyama, M.; Rivolta, I.; Thomas, M.A.; Kass, R.S.; Staub, O.; et al. Cardiac Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Nav Is Regulated by Nedd4-2 Mediated Ubiquitination. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.M.; Nathan, S.; Jiang, H.; Xia, W.; Kim, H.; Chakouri, N.; Nwafor, J.N.; Fossier, L.; Srinivasan, L.; Chen, Z.; et al. NEDD4L intramolecular interactions regulate its auto and substrate NaV1.5 ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 105715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Ning, F.; Du, Y.; Song, B.; Yang, D.; Salvage, S.C.; Wang, Y.; Fraser, J.A.; Zhang, S.; Ma, A.; et al. Calcium-dependent Nedd4-2 upregulation mediates degradation of the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5: Implications for heart failure. Acta Physiol. 2017, 221, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sun, G.; Wang, P.; Wang, W.; Cao, K.; Song, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N. Research progress of Nedd4L in cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, X.; Huang, C.; Mei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Ye, J.; Kong, B.; Liu, W.; et al. Loss of MD1 exacerbates pressure overload-induced left ventricular structural and electrical remodelling. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, M.; Struckman, H.L.; Olgar, Y.; Miller, A.; Demirtas, M.; Bogdanov, V.; Terentyeva, R.; Soltisz, A.M.; Meng, X.; Min, D.; et al. NaV1.6 dysregulation within myocardial T-tubules by D96V calmodulin enhances proarrhythmic sodium and calcium mishandling. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e152071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, B.M.; Gaa, J.; Hoppmann, P.; Martens, E.; Westphal, D.S. The Role of RYR2 in Atrial Fibrillation. Case Rep. Cardiol. 2023, 2023, 6555998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lou, Q.; Smith, H.; Velez-Cortes, F.; Dillmann, W.H.; Knollmann, B.C.; Armoundas, A.A.; Györke, S. Conditional Up-Regulation of SERCA2a Exacerbates RyR2-Dependent Ventricular and Atrial Arrhythmias. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.-E.; Liu, B.; Zhao, C.-X. Modulation of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release by ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component n-recognin UBR3 and 6 in cardiac myocytes. Channels 2020, 14, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.; Yang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Zou, Y.; Ye, P.; Zhu, L.; Wang, P.X.; Chen, M. LITAF acts as a novel regulator for pathological cardiac hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2021, 156, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Peng, L.; Ghista, D.N.; Wong, K.K.L. Left Atrial Remodeling Mechanisms Associated with Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2021, 12, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarbakhsh, S.; Schilling, R.J.; Orini, M.; Providencia, R.; Keating, E.; Finlay, M.; Sporton, S.; Chow, A.; Earley, M.J.; Lambiase, P.D.; et al. Structural remodeling and conduction velocity dynamics in the human left atrium: Relationship with reentrant mechanisms sustaining atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2019, 16, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Z.; Song, S.; Li, M.; Wang, T.; Sun, A.; Ge, J. Ubiquitin proteasome system in cardiac fibrosis. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 76, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangogiannis, N.G. Cardiac fibrosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 1450–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, H.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.-J.; Shi, K.-H. MicroRNA-21 via Dysregulation of WW Domain-Containing Protein 1 Regulate Atrial Fibrosis in Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, X.; Chen, C. WWP1: A versatile ubiquitin E3 ligase in signaling and diseases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qian, H.; Wu, B.; You, S.; Wu, S.; Lu, S.; Wang, P.; Cao, L.; Zhang, N.; Sun, Y. E3 Ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 family-regulatory network in cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 2727–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, H.; Wu, S.; Cao, L.; Sun, Y. Selective targeting of ubiquitination and degradation of PARP1 by E3 ubiquitin ligase WWP2 regulates isoproterenol-induced cardiac remodeling. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 2605–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, M.; He, Y.; Gui, C.; Wen, W.; Jiang, Z.; Zhong, G. Construction and integrated analysis of the ceRNA network hsa_circ_0000672/miR-516a-5p/TRAF6 and its potential function in atrial fibrillation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Gu, J.; Li, F.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, Y. Role of the MAPKs/TGF-β1/TRAF6 signaling pathway in atrial fibrosis of patients with chronic atrial fibrillation and rheumatic mitral valve disease. Cardiology 2014, 129, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.-X.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.-J.; Zhao, Y.-C.; Deng, K.-Q.; Jiang, X.; Wang, P.-X.; Huang, Z.; Li, H. The ubiquitin E3 ligase TRAF6 exacerbates pathological cardiac hypertrophy via TAK1-dependent signalling. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Guo, N.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yan, F.; Liao, H.; Chi, K. FBXW7 promotes pathological cardiac hypertrophy by targeting EZH2-SIX1 signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 393, 112059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-L.; Xiao, W.-C.; Li, H.; Hao, Z.-Y.; Liu, G.-Z.; Zhang, D.-H.; Wu, L.-M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Huang, Z.; et al. E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF5 attenuates pathological cardiac hypertrophy through STING. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Fang, Z.; Han, B.; Ye, B.; Lin, W.; Jiang, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, G.; Wang, Y.; et al. Deubiquitinase JOSD2 improves calcium handling and attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction by stabilizing SERCA2a in cardiomyocytes. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 2, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, M.; Qian, J.; Yu, T.; Lou, S.; Luo, W.; Zhou, H.; et al. JOSD2 mediates isoprenaline-induced heart failure by deubiquitinating CaMKIIδ in cardiomyocytes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, H.; Qu, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Kong, B.; Yang, H.; Shuai, W.; Huang, H. Ubiquitin-specific protease 38 modulates atrial fibrillation susceptibility in chronic kidney disease via STRAP stabilization and activation of TGF-β/SMAD signaling. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Yang, H.; Kong, B.; Meng, H.; Shuai, W.; Huang, H. USP38 exacerbates pressure overload-induced left ventricular electrical remodeling. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Pan, Y.; Kong, B.; Meng, H.; Shuai, W.; Huang, H. Ubiquitin-specific protease 38 promotes inflammatory atrial fibrillation induced by pressure overload. Europace 2024, 26, euad366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedai, H.; Altiparmak, I.H.; Tascanov, M.B.; Tanriverdi, Z.; Bicer, A.; Gungoren, F.; Demirbag, R.; Koyuncu, I. The relationship between oxidative stress and autophagy and apoptosis in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2022, 82, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanarek, N.; Ben-Neriah, Y. Regulation of NF-κB by ubiquitination and degradation of the IκBs. Immunol. Rev. 2012, 246, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menu, P.; Vince, J.E. The NLRP3 inflammasome in health and disease: The good, the bad and the ugly. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2011, 166, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, F.; Meng, W.; Zhang, F.; Hong, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, F. CYP2J2/EET reduces vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in chronic pressure overload mice. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samman Tahhan, A.; Sandesara, P.B.; Hayek, S.S.; Alkhoder, A.; Chivukula, K.; Hammadah, M.; Mohamed-Kelli, H.; O’Neal, W.T.; Topel, M.; Ghasemzadeh, N.; et al. Association between oxidative stress and atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2017, 14, 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balan, A.I.; Halațiu, V.B.; Scridon, A. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: A Link between Obesity and Atrial Fibrillation. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Cao, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, F.; Xi, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, R.; Xu, Y.; Xu, L. Mechanisms underlying altered ubiquitin-proteasome system activity during heart failure and pharmacological interventions. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 292, 117725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, G.; Dudley, S.C. Redox Regulation, NF-κB, and Atrial Fibrillation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2265–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes Júnior, A.d.S.; França-e-Silva, A.L.G.d.; Oliveira, J.M.d.; Silva, D.M.d. Developing Pharmacological Therapies for Atrial Fibrillation Targeting Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Liu, X.; Sha, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zu, Y.; Fan, Q.; Hu, L.; Sun, S.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, F.; et al. NEDD4–Mediated GSNOR Degradation Aggravates Cardiac Hypertrophy and Dysfunction. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathman, S.G.; Span, I.; Smith, A.T.; Xu, Z.; Zhan, J.; Rosenzweig, A.C.; Statsyuk, A.V. A Small Molecule That Switches a Ubiquitin Ligase From a Processive to a Distributive Enzymatic Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 12442–12445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirit, J.G.; Lavrenov, S.N.; Poindexter, K.; Xu, J.; Kyauk, C.; Durkin, K.A.; Aronchik, I.; Tomasiak, T.; Solomatin, Y.A.; Preobrazhenskaya, M.N.; et al. Indole-3-carbinol (I3C) analogues are potent small molecule inhibitors of NEDD4-1 ubiquitin ligase activity that disrupt proliferation of human melanoma cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 127, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronchik, I.; Kundu, A.; Quirit, J.G.; Firestone, G.L. The antiproliferative response of indole-3-carbinol in human melanoma cells is triggered by an interaction with NEDD4-1 and disruption of wild-type PTEN degradation. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 1621–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, J.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Meng, B. Effects of ubiquitin-proteasome inhibitor on the expression levels of TNF-α and TGF-β1 in mice with viral myocarditis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 2799–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-M.; Li, Y.-C.; Chen, P.; Ye, S.; Xie, S.-H.; Xia, W.-J.; Yang, J.-H. MG-132 attenuates cardiac deterioration of viral myocarditis via AMPK pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 126, 110091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, H.-X.; Li, N.; Deng, Y.-W.; Bi, H.-L.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Xia, Y.-L.; Li, H.-H. Selective Inhibition of the Immunoproteasome β5i Prevents PTEN Degradation and Attenuates Cardiac Hypertrophy. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.-L.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Yang, J.; Shu, Q.; Yang, X.-L.; Yan, X.; Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Li, H.-H. Inhibition of UCHL1 by LDN-57444 attenuates Ang II–Induced atrial fibrillation in mice. Hypertens. Res. 2019, 43, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriend, J.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin and ubiquitin: What’s the connection? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 3409–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Gu, S.; Han, Y.; Li, L.; Jia, Z.; Gao, N.; Liu, Y.; Lin, S.; Hou, Y.; et al. Effect of optimized new Shengmai powder on exercise tolerance in rats with heart failure by regulating the ubiquitin-proteasome signaling pathway. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1168341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, R.; Pu, Z.; Chen, Z. Targeting the Ubiquitin–Proteasome System in Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanistic Insights and Translational Perspectives. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010046

Huang R, Pu Z, Chen Z. Targeting the Ubiquitin–Proteasome System in Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanistic Insights and Translational Perspectives. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Runze, Zhipeng Pu, and Zhangrong Chen. 2026. "Targeting the Ubiquitin–Proteasome System in Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanistic Insights and Translational Perspectives" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010046

APA StyleHuang, R., Pu, Z., & Chen, Z. (2026). Targeting the Ubiquitin–Proteasome System in Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanistic Insights and Translational Perspectives. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010046