Anticancer Effects of Combined Blue Light and Ionizing Irradiation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.3. Blue Light Irradiation

2.4. In Vitro X-Ray Irradiation

2.5. Colony Formation Assay

2.6. SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

2.7. Analysis of Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species

2.8. Analysis of Apoptosis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Blue Light Irradiation on Human Cancer Cell Proliferation

3.2. Effects of Combined Exposure to Blue Light and Radiation on Human Cancer Cell Proliferation

3.3. Effects of Combined Exposure to Blue Light and Radiation on Intracellular ROS Levels in HNSCC Cells

3.4. Involvement of ERK1/2 on the Anticancer Effects of Blue Light and in Combination with Ionizing Radiation in HNSCC Cells

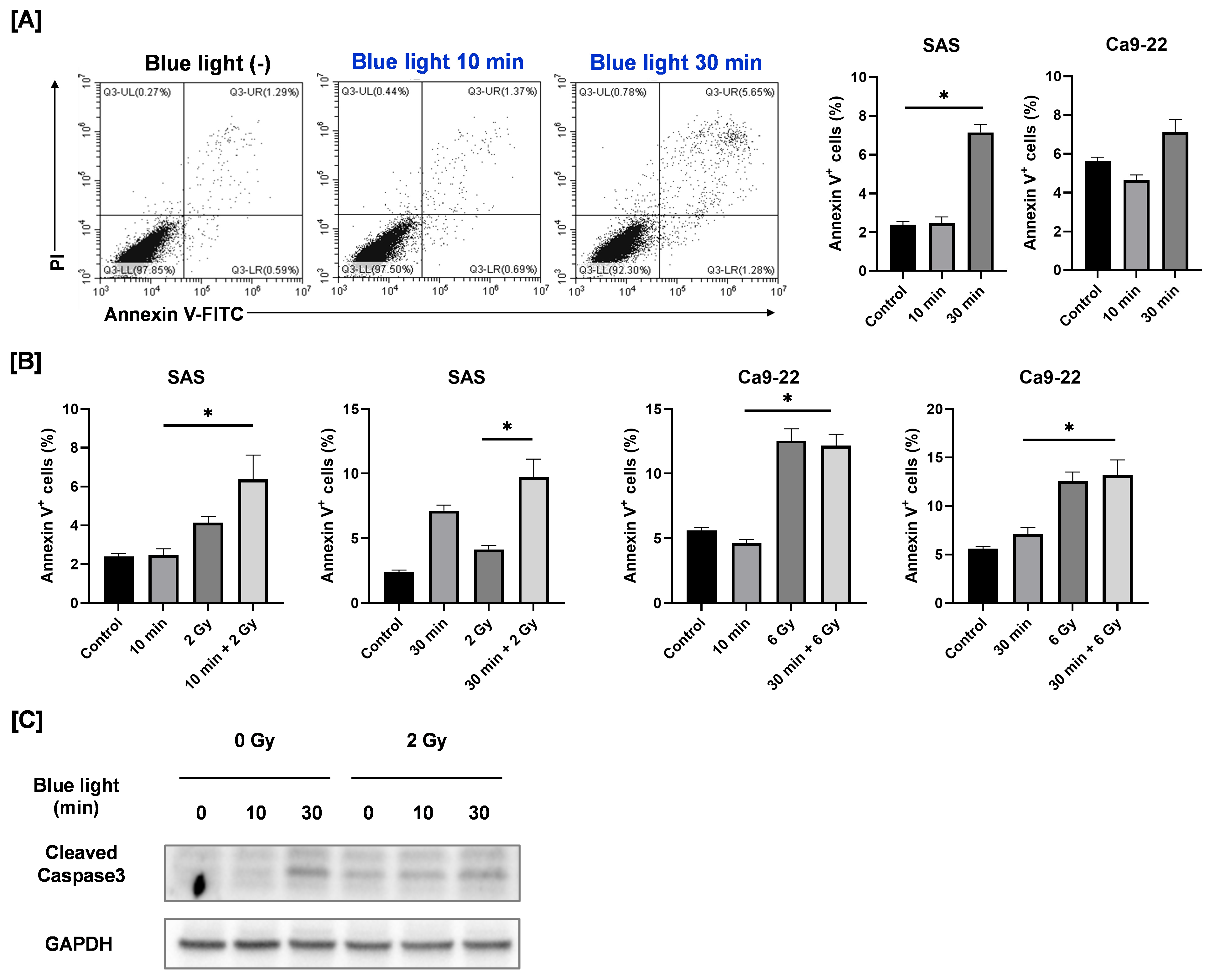

3.5. Apoptosis-Inducing Effects of Blue Light Alone or in Combination with Ionizing Radiation in HNSCC Cells

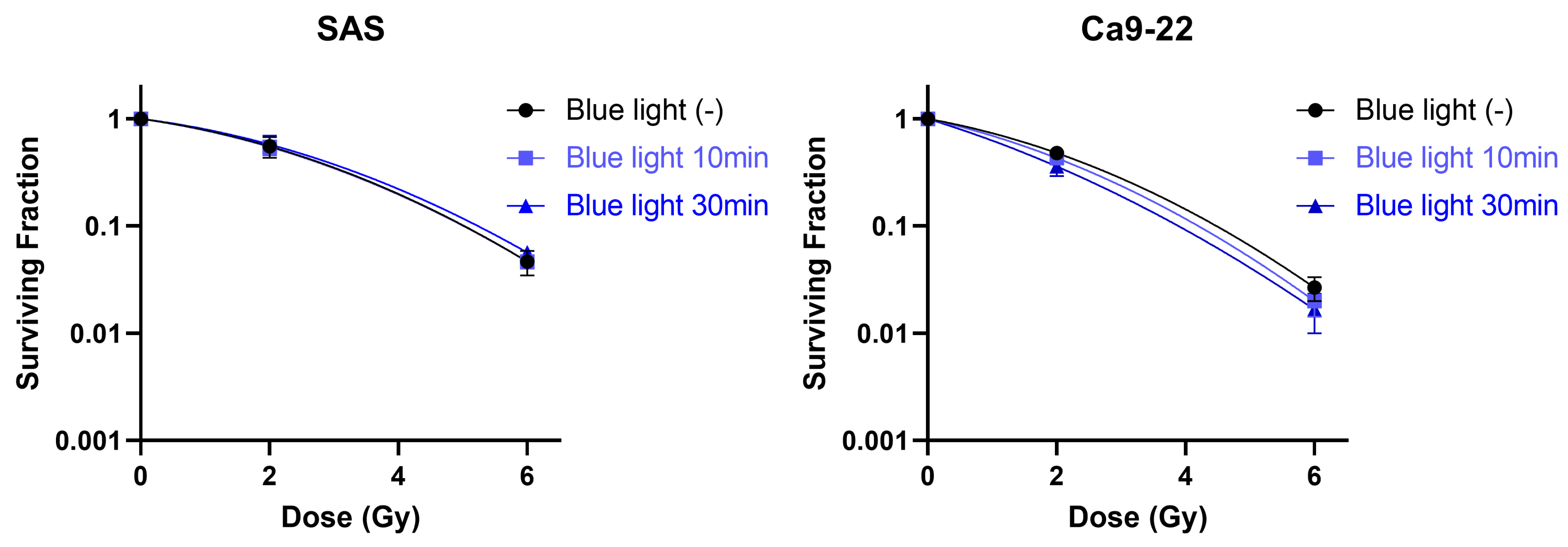

3.6. Effects of Blue Light Irradiation Radiosensitivity of HNSCC Cells

3.7. Effects of Blue Light Irradiation and Combined Exposure to Blue Light and Radiation on HUVECs Proliferation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

References

- Lipko, N.B. Photobiomodulation: Evolution and adaptation. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2022, 40, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-Y.; Lee, M.Y. Photobiomodulation of neurogenesis through the enhancement of stem cell and neural progenitor differentiation in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, M.L.G.; Campos, T.M.; Fonseca, E.S.R.; Pavani, C.; Horliana, A.C.R.T.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Bussadori, S.K.; Fantin, F.G.M.M.; Leite, D.P.V.; Yamamoto, Â.T.A. Effect of blue light on acne vulgaris: A systematic review. Sensors 2021, 21, 6943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraccalvieri, M.; Amadeo, G.; Bortolotti, P.; Ciliberti, M.; Garrubba, A.; Mosti, G.; Bianco, S.; Mangia, A.; Massa, M.; Hartwig, V.; et al. Effectiveness of blue light photobiomodulation therapy in the treatment of chronic wounds. Results of the Blue Light for Ulcer Reduction (B.L.U.R.) study. Ital. J. Dermatol. Venerol. 2022, 157, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Ko, S.; Shin, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, T.; Jung, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, N.G.; Park, K.; Ryu, J.H. Light-emitting diode irradiation induces Akt/mtor-mediated apoptosis in human pancreatic cancer cells and xenograft mouse model. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 1362–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, H.; Fu, Q.; Qin, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, M. Blue light photobiomodulation induced apoptosis by increasing ROS level and regulating SOCS3 and PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway in osteosarcoma cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2023, 249, 112814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunckhorst, M.K.; Lerner, D.; Wang, S.; Yu, Q. AT-406, an orally active antagonist of multiple inhibitor of apoptosis proteins, inhibits progression of human ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2012, 13, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Q. Short-chain C6 ceramide sensitizes AT406-induced anti-pancreatic cancer cell activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 479, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, E.; Kawamoto, T.; Ueha, T.; Hara, H.; Fukase, N.; Minoda, M.; Morishita, M.; Takemori, T.; Fujiwara, S.; Nishida, K.; et al. Synergistic effects of a SMAC mimetic with doxorubicin against human osteosarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 6097–6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalli, A.D.; Brown, L.E.; Thomas, C.L.; Sayers, T.J.; Porco, J.A.; Henrich, C.J. Sensitization of renal carcinoma cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by rocaglamide and analogs. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhu, G.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Wei, Y. The strong inhibitory effect of combining anti-cancer drugs AT406 and rocaglamide with blue LED irradiation on colorectal cancer cells. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 30, 101797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, H.; Iwabuchi, M.; Kazama, Y.; Furukawa, M.; Kashiwakura, I. Effects of retinoic acid-inducible gene-I-like receptors activations and ionizing radiation cotreatment on cytotoxicity against human non-small cell lung cancer in vitro. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 4697–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, H.; Kumai, Y.; Kashiwakura, I. Effects of endoplasmic reticulum stress on apoptosis induction in radioresistant macrophages. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 2867–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendtner, N.; Seitz, R.; Brandl, N.; Müller, M.; Gülow, K. Reactive Oxygen Species Across Death Pathways: Gatekeepers of Apoptosis, Ferroptosis, Pyroptosis, Paraptosis, and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, H.; Pal, S.; Sabnam, S.; Pal, A. High glucose augments ROS generation regulates mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis via stress signalling cascades in keratinocytes. Life Sci. 2020, 241, 117148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roskoski, R. ERK1/2 MAP kinases: Structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol. Res. 2012, 66, 105–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Taghizadeh, S.; Kaviani, E.; Vakili, O.; Taheri-Anganeh, M.; Tahamtan, M.; Savardashtaki, A. Caspase-3: Structure, function, and biotechnological aspects. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Teng, L.; Li, H. Proliferation inhibition and apoptosis of liver cancer cells treated by blue light irradiation. Med. Oncol. 2023, 40, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, T.; Morine, Y.; Takasu, C.; Feng, R.; Ikemoto, T.; Yoshikawa, K.; Iwahashi, S.; Saito, Y.; Kashihara, H.; Akutagawa, M. Blue light-emitting diodes induce autophagy in colon cancer cells by opsin 3. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2018, 2, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, N.; Yoshikawa, K.; Shimada, M.; Kurita, N.; Sato, H.; Iwata, T.; Higashijima, J.; Chikakiyo, M.; Nishi, M.; Kashihara, H.; et al. Effect of light irradiation by light emitting diode on colon cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 4709–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Nishisho, T.; Toki, S.; Kawaguchi, S.; Tamaki, S.; Oya, T.; Uto, Y.; Katagiri, T.; Sairyo, K. Blue light induces apoptosis and autophagy by promoting ROS-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction in synovial sarcoma. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 9668–9683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Y.; Zhang, K.; Xu, D.; Zhou, W.-T.; Fang, W.-Q.; Wan, Y.-Y.; Yan, D.-D.; Guo, M.-Y.; Tao, J.-X.; Zhou, W.C.; et al. Mitochondrial fission is required for blue light-induced apoptosis and mitophagy in retinal neuronal R28 cells. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, X.; Wu, F.; Cao, X.; Gou, K.; Wang, C.; Lin, C. Blue light induces skin apoptosis and degeneration through activation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress-autophagy apoptosis axis: Protective role of hydrogen sulfide. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2022, 229, 112426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, T.; Kishi, R.; Sato, K.; Sato, K. Blue light exposure enhances oxidative stress, causes DNA damage, and induces apoptosis signaling in B16F1 melanoma cells. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2022, 883–884, 503562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, D. Blue light-induced apoptosis of human promyelocytic leukemia cells via the mitochondrial-mediated signaling pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 6291–6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, M.Y.; Novak, K.; Haqqi, T.M. ERK1/2-mediated activation of DRP1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis in chondrocytes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2022, 30, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, M.; Forman, H.J. Redox signaling and the MAP kinase pathways. Biofactors 2003, 17, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omata, Y.; Lewis, J.B.; Rotenberg, S.; Lockwood, P.E.; Messer, R.L.W.; Noda, M.; Hsu, S.D.; Sano, H.; Wataha, J.C. Intra- and extracellular reactive oxygen species generated by blue light. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2006, 77A, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Zhao, C.; Li, G.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; Yan, P.; Wei, S. Blue LED light induces cytotoxicity via ROS production and mitochondrial damage in bovine subcutaneous preadipocytes. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 322, 121195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.S. Apoptosis in cancer: From pathogenesis to treatment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 30, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maya-Cano, D.A.; Arango-Varela, S.; Santa-Gonzalez, G.A. Phenolic compounds of blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) as a protective strategy against skin cell damage induced by ROS: A review of antioxidant potential and antiproliferative capacity. Heliyon 2021, 7, 6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradt, B. Genetic control of programmed cell death during animal development. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009, 43, 493–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Kepp, O.; Kroemer, G. Regulated cell death and adaptive stress responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 2405–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Song, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, K.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Su, S.; Li, Z. Short-wavelength blue light contributes to the pyroptosis of human lens epithelial cells (HLECs). Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 212, 108786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Fu, Q.; Jiang, H.; Zhong, H.; Qin, H.K.; Miao, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Yao, J. Blue light photobiomodulation induced osteosarcoma cell death by facilitating ferroptosis and eliciting an incomplete tumor cell stress response. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2024, 258, 113003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, K.; Mu, Y.; Bouschbacher, M.; Sticht, C.; Kuch, N.; Sigl, M.; Rahbari, N.; Gretz, N.; Pallavi, P.; Keese, M. Biphasic Effects of Blue Light Irradiation on Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kitano, K.; Yoshino, H.; Kawanami, K.; Kajimoto, R.; Tsuruga, E. Anticancer Effects of Combined Blue Light and Ionizing Irradiation. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010045

Kitano K, Yoshino H, Kawanami K, Kajimoto R, Tsuruga E. Anticancer Effects of Combined Blue Light and Ionizing Irradiation. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleKitano, Keita, Hironori Yoshino, Kosuke Kawanami, Ryosuke Kajimoto, and Eichi Tsuruga. 2026. "Anticancer Effects of Combined Blue Light and Ionizing Irradiation" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010045

APA StyleKitano, K., Yoshino, H., Kawanami, K., Kajimoto, R., & Tsuruga, E. (2026). Anticancer Effects of Combined Blue Light and Ionizing Irradiation. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010045