1. Introduction

Acne vulgaris (referred to as acne hereafter), a multifactorial chronic inflammatory skin disorder with a global prevalence exceeding 85% among young adults, profoundly impacts the physical appearance and psychological well-being of adolescents [

1,

2]. Given its high prevalence, chronic recurrence, and potential to cause permanent scarring, acne represents a significant public health issue, frequently contributing to prolonged emotional distress, social isolation, and diminished self-esteem among affected individuals [

3,

4,

5].

The pathogenesis of acne is multifaceted, involving intricate interactions among four primary factors: androgen-dependent hyper-seborrhea, follicular hyper-keratinization, inflammation, and microbial dysbiosis [

1]. Central to acne pathogenesis is the role of

Cutibacterium acnes (

C. acnes, formerly

Propionibacterium acnes), a gram-positive, anaerobic bacterium that colonizes the pilosebaceous follicle as part of the normal skin microbiota [

6]. In healthy skin,

C. acnes contributes to microbial homeostasis by producing antimicrobial peptides and maintaining an acidic pH that inhibits pathogenic invaders [

7]. However, in acne-prone individuals, an imbalance in the skin microenvironment—such as increased sebum providing a nutrient-rich niche—can lead to the over-proliferation of specific

C. acnes phylotypes, triggering inflammatory cascades [

8]. Recent research has emphasized that acne development is not solely due to bacterial overgrowth but rather an imbalance among

C. acnes phylotypes, with a loss of diversity serving as a key trigger for innate immune activation [

9,

10]. Among the six major phylotypes (IA

1, IA

2, IB, IC, II, III), phylotype IA

1 demonstrates increased virulence and antibiotic tolerance, which is attributed to enhanced biofilm formation, stronger adhesion to keratinocytes, and elevated secretion of pro-inflammatory factors such as extracellular vesicles, lipases, and porphyrins [

11,

12,

13]. Studies have shown a predominance of phylotype IA

1 in acne lesions compared to healthy skin, where it alters the natural stratum corneum lipid ratio, invades follicular keratinocytes, dysregulates epidermal barrier function, and induces cytokine release and immune cell recruitment [

10,

12,

14,

15,

16]. Moreover, recent studies have shown that the phylotype IA

1’s interaction with follicular keratinocytes and cells in the sebaceous duct amplifies inflammation through pattern recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), leading to NF-κB pathway activation and production of interleukins (e.g., IL-6, IL-8) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [

15,

17,

18,

19]. However, there remains a gap in understanding the biological effects of

C. acnes IA

1 on epidermal keratinocytes, particularly with regard to the precise host transcriptional responses induced by this phylotype.

This investigation aims to delineate the regulatory mechanisms of C. acnes IA1 in acne pathogenesis, with a focus on identifying core genes, biological functions, and signaling pathways through integrated transcriptomics and network pharmacology. By constructing a PPI network and performing enrichment analyses, we seek to pinpoint hub genes that modulate sebaceous gland inflammation, immune cell activity, and keratinocyte proliferation. We selected C. acnes CICC 10864 (equivalent to ATCC 6919) as a representative IA1 reference strain, widely utilized in acne research for its well-characterized virulence profile.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

The human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT was purchased from Shanghai Chuanqiu biotechnology company. HaCaT cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) without antibiotics and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

2.2. Bacterial Culture

C. acnes (CICC 10864) belonging to phylotype IA1 was purchased from China Center of Industrial Culture Collection (Beijing, China) and cultured on Reinforced Clostridial Agar Medium (RCM) at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions using anaerobic atmosphere generation systems (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Company, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Briefly, plates or slants were placed in rectangular jars containing an AnaeroPack and incubated at 37 °C. Then, C. acnes IA1 (CICC 10864) was inoculated onto an agar slant medium and cultured for 24 h, after which the growth was harvested using an inoculating loop and washed with a 0.85% saline solution. The resulting bacterial pellet was resuspended in 0.85% saline to obtain a uniform bacterial suspension and adjusted by dilution to an absorbance of OD625nm = 1.0, corresponding to approximately 1 × 109 CFU/mL. The bacterial cell concentration was accurately determined using a pre-established standard curve correlating OD625nm readings with cell counts (y = 0.9541x + 0.0358, R2 = 0.968).

2.3. Co-Culture of Keratinocytes with C. acnes IA1

At first, HaCaT cells were seeded in 96-well plates and 60 mm culture dishes at a seeding density of 1 × 105 cells per well and 5 × 106 cells per dish, respectively. The cells were allowed to attach for 24 h, which would grow to reach 95% confluency. Then, the HaCaT cells were treated with C. acnes IA1 (CICC 10864) at multiplicity of infection (MOI) for 24 h. Briefly, the culture medium was replaced with a different concentration of bacterial suspension obtained as above. Then, HaCaT and C. acnes IA1 (CICC 10864) were co-cultured at 37 °C/5% CO2 for 24 h.

2.4. RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from the cell using TRIzol Reagent (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and purified using an RNA Purification Kit (Shanghai Majorbio, Shanghai, China) according the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and purity of the isolated RNA were assessed using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Shanghai, China). RNA integrity was evaluated through agarose gel electrophoresis, and the RQN value was determined using a 5300 Fragment Analyzer System (Agilent Technologies, Beijing, China). For individual sequencing library construction, a minimum of 1 μg total RNA is required, with a concentration of at least 30 ng/μL, an RQN value greater than 6.5, an OD260/280 ratio ranging between 1.8 and 2.2, OD260/OD230 greater than 2.0, and 28/23S rRNA band brightness exceeding that of 18/16S rRNA.

2.5. Library Preparation and Sequencing

RNA purification, reverse transcription, library construction, and sequencing were performed at Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The XX RNA-seg transcriptome library was prepared following Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, Ligation (Illumina, Inc., Shanghai, China) using 1 μg of total RNA. Shortly, messenger RNA was isolated according to the polyA selection method by oligo (dT) beads and then fragmented by a fragmentation buffer. Next, double-stranded cDNA was synthesized using an InvitrogenTM SuperScript double-stranded cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) with random hexamer primers. Then, the synthesized cDNA was subjected to end-repair, phosphorylation, and adapter addition according to the library construction protocol. Libraries were size selected for cDNA target fragments of 300 bp on 2% Low Range Ultra Agarose followed by PCR amplified using Phusion DNA polymerase (NEB) for 15 PCR cycles. After quantification by Qubit 4.0, the sequencing library was performed on the NovaSeq X Plus platform (PE1 50) using the Illumina NovaSeg Reagent Kit (Illumina, Inc.).

2.6. Differential Expression Gene Analysis

To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between two distinct samples, the expression level of each transcript was estimated using the transcripts per million (TPM) method. Gene abundance quantification was carried out with RSEM. Subsequently, differential expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2. Genes exhibiting a |log2 fold change (FC)| ≥ 1 and a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 (as determined by DESeq2) were considered significantly differentially expressed.

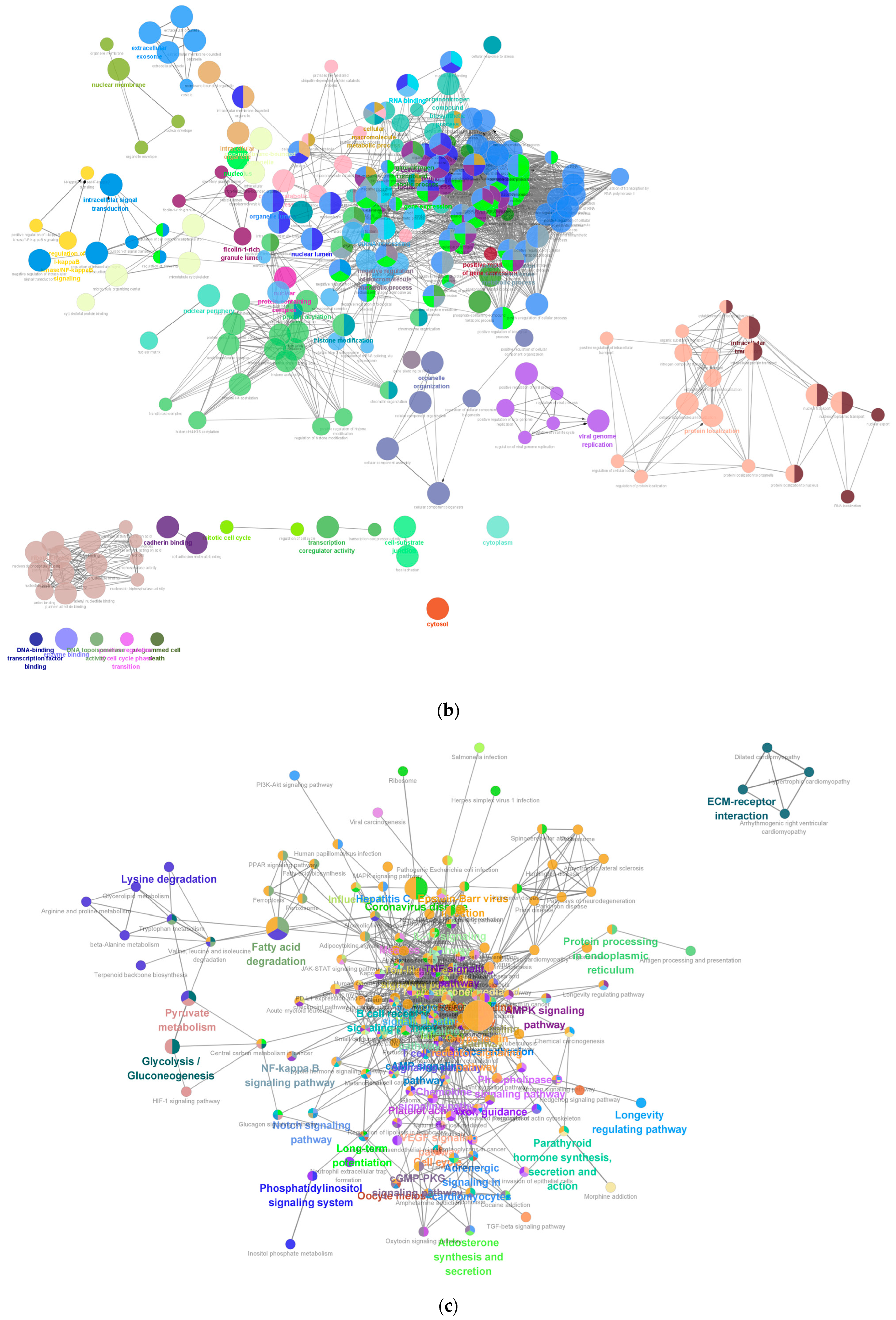

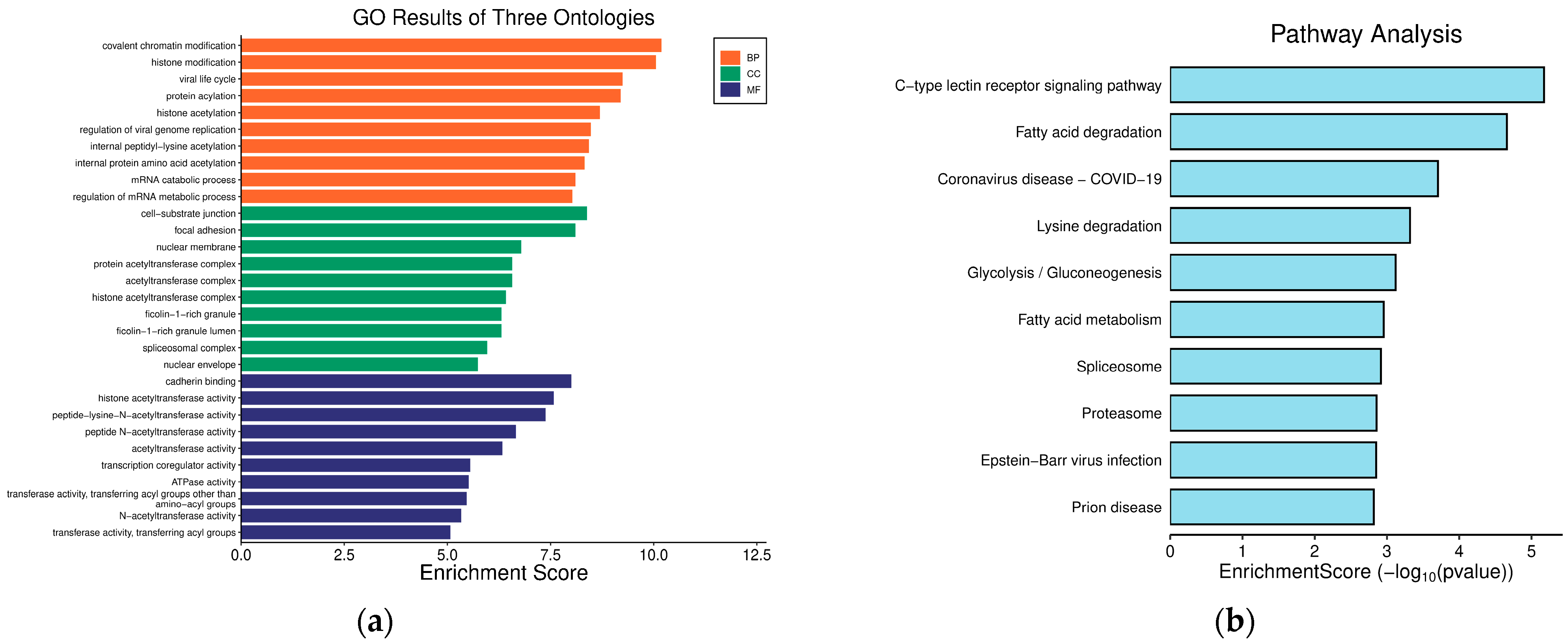

2.7. Functional Enrichment Analyses of Hub Genes

Functional enrichment analysis including GO and KEGG were performed to identify which DEGs were significantly enriched in GO terms and which metabolic pathways had a Bonferroni-corrected p-value ≤ 0.05 compared with the whole-transcriptome background. GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis were carried out by Goatools (version 0.12.1) and Python scipy (version 1.10.1) software, respectively.

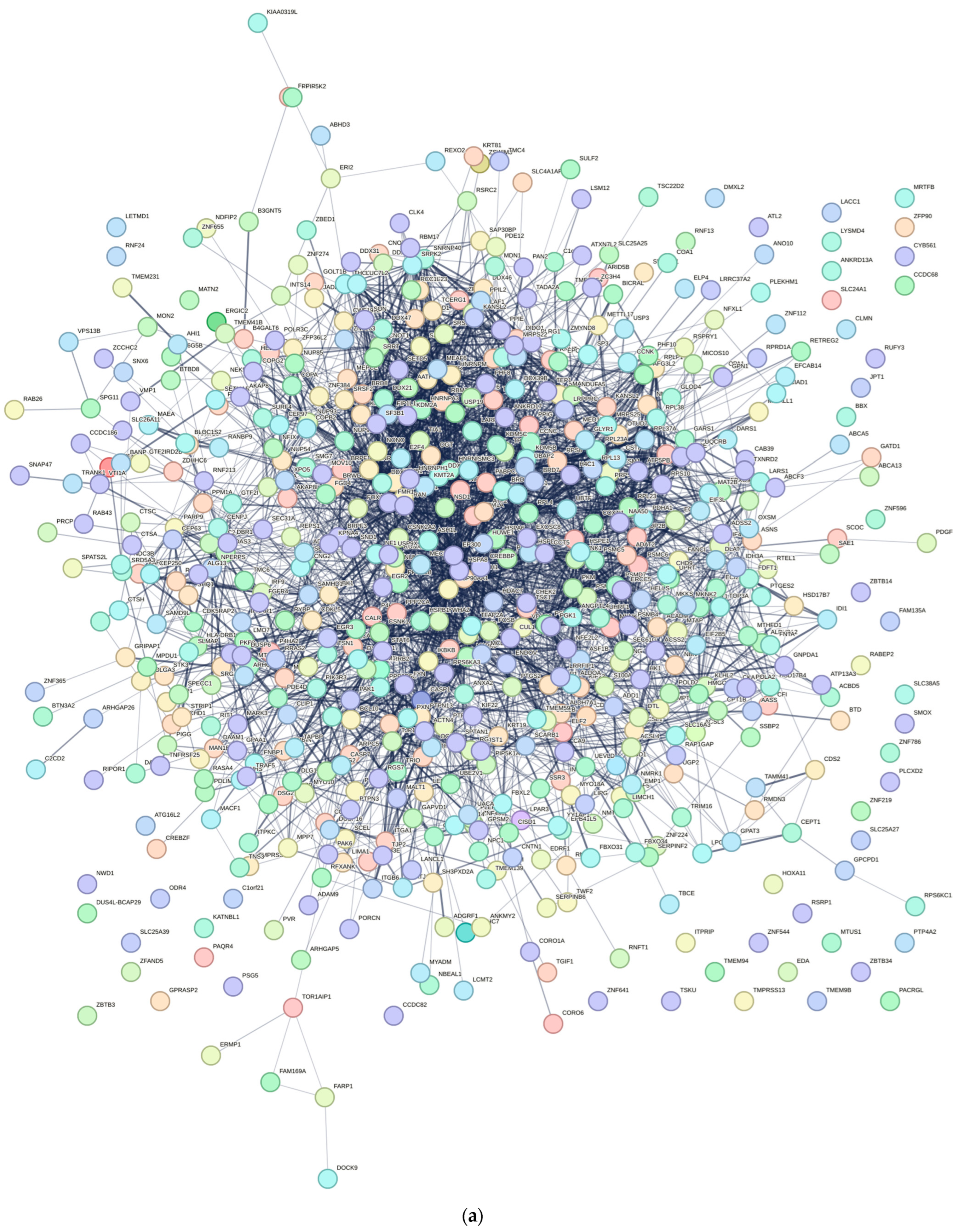

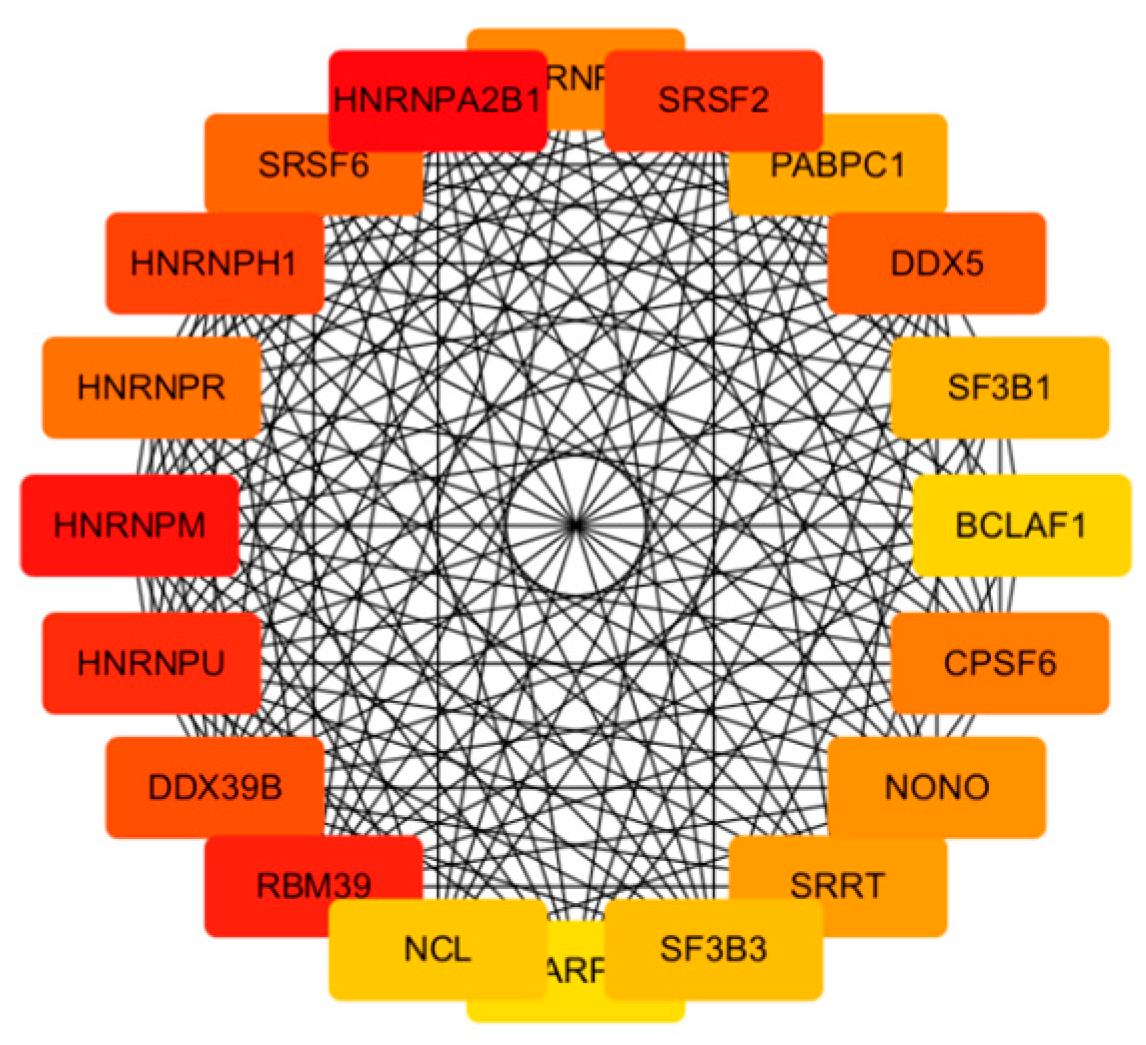

2.8. PPI Network Construction and Key Genes Identification

To investigate the interactions among DEGs and identify potential key genes, a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using data from the STRING database. Only interactions with a combined score ≥ 0.7 (indicating high confidence) were retained for network construction. This constructed PPI network was later visualized using Cytoscape Software (version 3.10.2). We then calculated the top 20 significant nodes within the PPI network based on their degrees using cytohubba, an extension of Cytoscape. These 20 calculated nodes were recognized as candidate key genes (hub genes) associated with C. acnes.

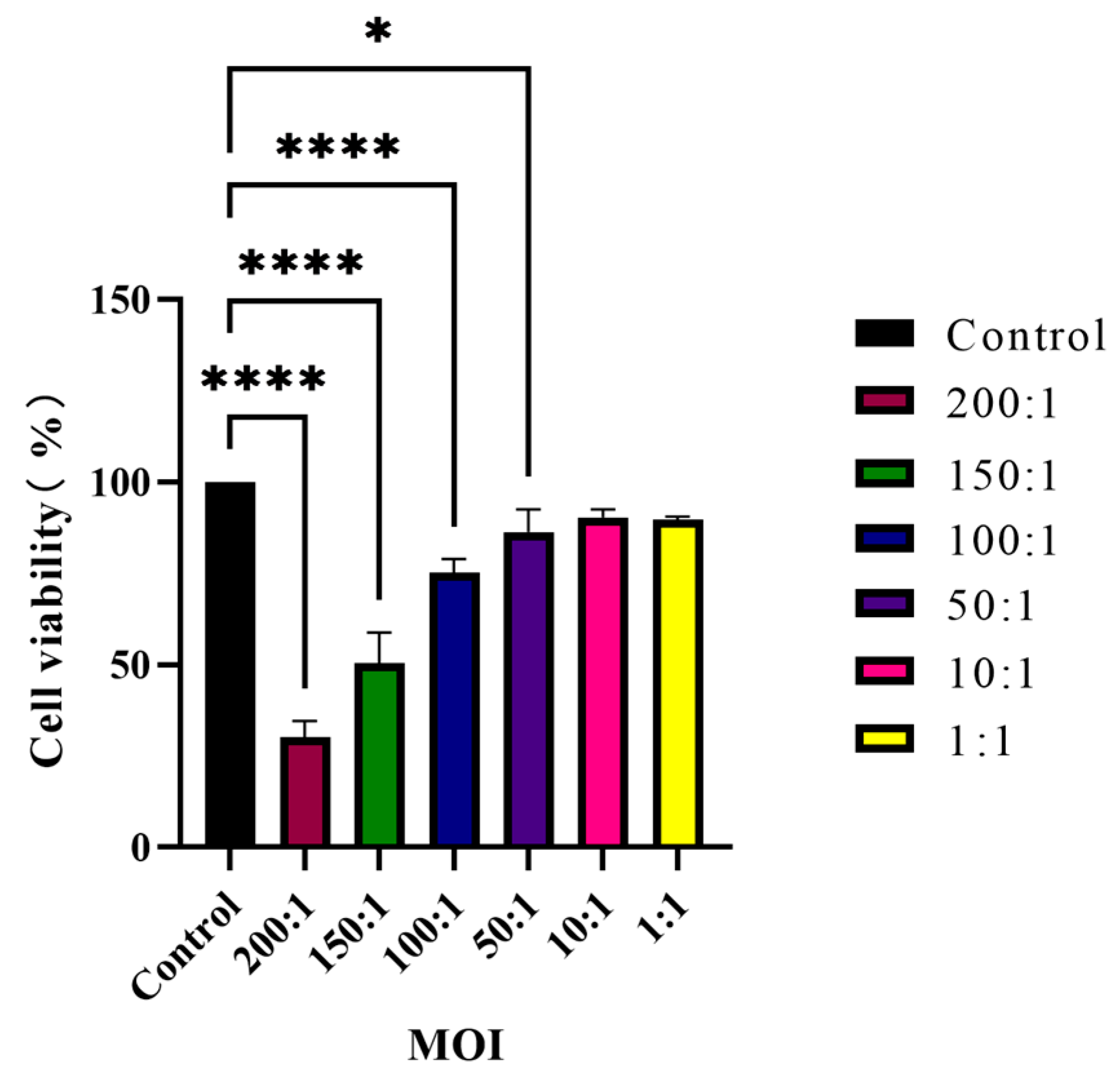

2.9. Host Cell Viability Assay

HaCaT cells seeded in 96-well plates were co-cultured with

C. acnes IA

1 (CICC 10864) at MOIs of 200:1, 150:1, 100:1, 50:1, 10:1, and 1:1. Meanwhile, the corresponding series of bacterial suspension concentrations cultured without keratinocytes served as blank controls, whereas keratinocytes cultured without bacteria were defined as negative controls. After 24 h, cell viability was determined by using cell-counting kit 8 (CCK-8, Beyotime Biotechnology). Firstly, the culture medium was removed by aspiration and centrifugated at 13,000×

g for 5 min. The supernatant was then collected and stored at −80 °C for further experimental use. Next, a CCK-8-containing medium was added to each well and incubated for 1 h in a CO

2 incubator at 37 °C. The absorbance value was measured on a Spark Multimode Microplate Reader (Tecan Trading AG) with a test wavelength of 450 nm and a reference wavelength of 630 nm.

AS: The absorbance of keratinocytes co-cultured with bacteria cells.

Anc: The absorbance of keratinocytes cultured without bacteria cells.

Abc: The absorbance of bacteria cells cultured without keratinocytes.

2.10. Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Using ELISA Assay

The supernatant collected above (

Section 2.9) was used to determine the IL-6 secretion without dilution using an ELISA immunoassays kit (Beijing Shengyan Biology, Beijing, China). The secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 was determined by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with a linearity range of 1.5–48 pg/mL. Three technical replicates were performed for each sample. The absorbance value of each sample was measured at 450 nm using a Spark Multimode Microplate Reader (Tecan Trading AG, Shanghai, China).

2.11. Calculation of the Cytokine Secretion

In order to reduce any variation due to the differences in cell density, the normalized cytokine secretion values were adjusted by the cell viability using the following equation:

The cells not treated with C. acnes IA1 were designated as the control group, which had a viability of 1, and the relative viability of the treated groups was compared to that of the control group.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 9.0.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates or three independent experiments. Paired t-test or ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to identify significant variations. p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

2.13. Bacterial Cell Tracing

To analyze the presence of bacteria, C. acnes IA1 (CICC 10864) was stained with CytoTrace™ UltraGreen (AAT Bioquest, Pleasanton, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the bacterial cells were treated with CytoTrace™ UltraGreen for 30 min at 37 °C and then added to HaCaT cells at an MOI of 100:1 for 24 h. Then, the floating bacteria were removed by washing 3 times with PBS. The cells were fixed on ice with a 4% formaldehyde solution in PBS for 15 min and then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were stained by Phalloidin-AF594 (Cohesion Biosciences, London, UK) for 20 min, followed by Hoechst 33342 (Beyotime Biotechnology) for 5 min according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were observed by using ZEISS Axiovert 5 fluorescence microscopy (ZEISS, Jena, Germany).

2.14. Bacterial Quantification

To quantify the viability of bacteria attached to the host cell, bacterial counting by qPCR was performed as follows. HaCaT cells were cultured on 60 mm dishes, followed by treatment with C. acnes at an MOI of 100:1 for 24 h. The culture medium was collected. Subsequently, the cells were gently washed three times with 1 mL of PBS, then the washing buffer was collected and combined with the culture medium to obtain the non- associated bacteria. In addition, the keratinocyte cells were lysed by adding 2 mL of sterile distilled water, incubating for 5 min at room temperature to induce cell swelling, and pipetting up and down gently until complete cell rupture was achieved to release the potentially adherent or invasive bacteria, and the extract was collected. Total DNA was isolated from the bacteria cells by using the GeneJET™ Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration and purity were determined by standard spectrophotometric methods using a NanoVue™ Plus Spectrophotometer (Richmond Scientific, Lancashire, UK) with an OD260/280 ratio ranging between 1.8 and 2.0. Real-time PCR targeted on a bacterial 16S rRNA gene was carried out to detect the copy numbers of the samples with primers specific for C. acnes (PA1-129F: 5′- GACTTTGGGATAACTTCAGGAAACTG -3′, PA1-238R: 5′- CTGATAAGCCGCGAGTCCAT -3′) using the SYBR Green PCR master mix (Sparkjade, Jinan, China) and the Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The thermal cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 30 s; a final hold at 95 °C for 10 s; and melt curve analysis. The amplification specificity was confirmed by melting curve analysis. The data were calculated by using the standard curve method for absolute quantification (y = −3.738x + 40.337, E = 85.4%, R2 = 0.996, slope = −3.730). In addition, the preparation of the standard template was as follows. DNA of the reference strain C. acnes CICC10864 was used as the template for full-length amplification of the 16S rDNA gene fragment using bacterial universal primers (27F: 5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′; 1429R: 5′-TACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). The amplification was carried out under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min; 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 50.4 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 90 s; a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min; and holding at 4 °C. PCR amplicons were run on 1% agarose TAE gels. Then, 16S rDNA at 1500 bp were extracted by following the GeneJET™ Gel Extraction Kit manufacturer’s protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the purity and concentration of extracted DNA were measured by using the NanoVue™ Plus Spectrophotometer (Richmond Scientific) with an OD260/280 ratio ranging between 1.8 and 2.0. Then, the copy number was calculated and corrected. The extracted 16S rDNA were used as a standard template for construction of standard curves.

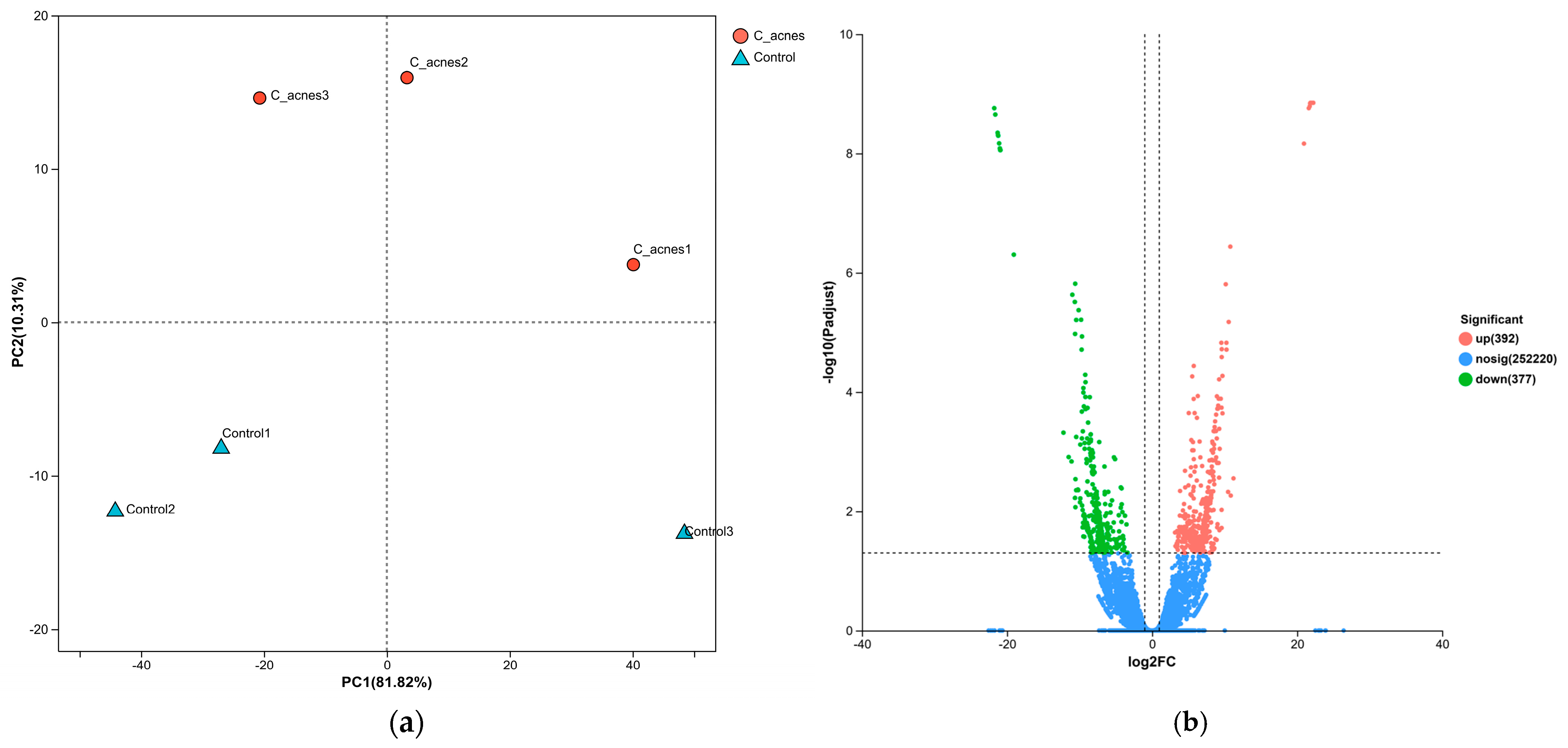

4. Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying

Cutibacterium acnes IA

1–driven acne pathogenesis through transcriptomic profiling of infected HaCaT keratinocytes. By integrating RNA sequencing with network pharmacology, we identified 769 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with 392 upregulated and 377 downregulated, reflecting profound transcriptional reprogramming in response to

C. acnes IA

1. The distinct clustering observed in the principal component analysis (PCA) underscores the robust impact of bacterial infection on keratinocyte gene expression, likely driven by inflammatory signaling and cellular stress responses [

20]. These findings align with prior reports that

C. acnes IA

1, a virulent phylotype, triggers innate immune activation in acne-prone skin, contributing to chronic inflammation and lesion formation [

15,

21].

Central to our findings are the hub genes HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPM, and RBM39, identified through the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis as key regulators of acne pathogenesis. HNRNPA2B1, a heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein, modulates RNA splicing and stability, and its upregulation in infected keratinocytes may enhance the expression of pro-inflammatory transcripts, such as those encoding cytokines like IL-6 [

22]. This is consistent with our observation of significantly elevated IL-6 levels (

p < 0.01), a cytokine known to promote keratinocyte proliferation and sebocyte differentiation in acne [

23]. HNRNPM, involved in alternative splicing, likely contributes to follicular hyper-keratinization by dysregulating genes associated with keratinocyte differentiation, a hallmark of comedogenesis. Similarly, RBM39, a splicing factor interacting with U2AF65, may amplify inflammatory signaling by modulating C-JUN phosphorylation, mimicking pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that activate innate immunity [

24]. These hub genes collectively regulate sebaceous gland inflammation, immune cell recruitment, and epidermal proliferation, positioning them as promising biomarkers for acne severity and potential therapeutic targets. For instance, elevated HNRNPA2B1 expression could serve as a diagnostic indicator in acne lesions, enabling personalized interventions targeting RNA processing pathways [

20].

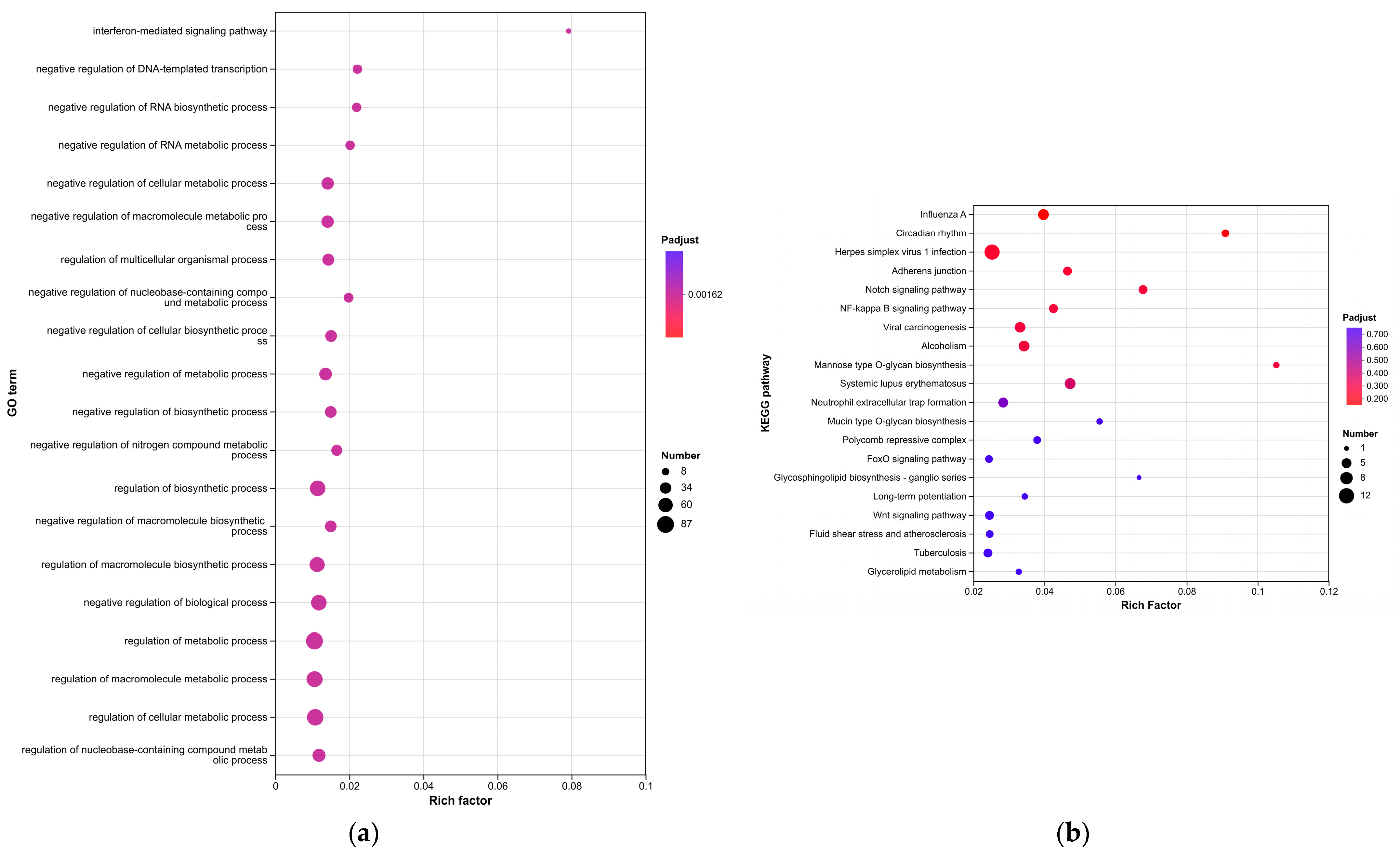

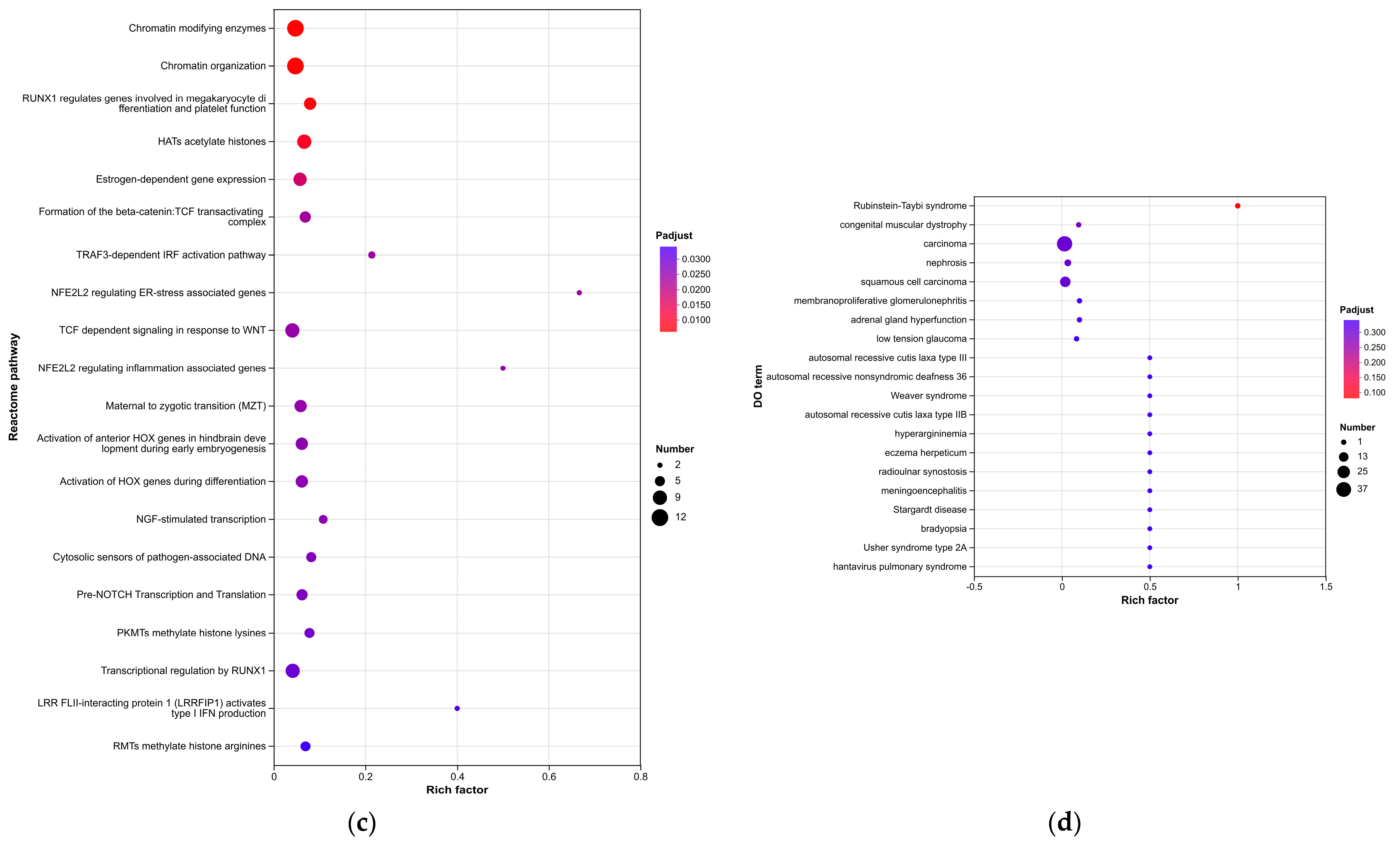

Enrichment analyses, grouped by functional categories (

Table 3), revealed a predominance of RNA processing and immune response pathways consistent with

C. acnes-induced inflammation. These analyses further identified the C-type lectin receptor (CLR) signaling pathway as a key mediator of

C. acnes IA

1–induced inflammation. CLRs, expressed on keratinocytes and immune cells, recognize bacterial glycans, activating NF-κB and MAPK pathways to drive cytokine production [

25]. Our KEGG results, which also enriched NF-κB signaling, suggest a synergistic mechanism where

C. acnes IA

1 exploits CLR-mediated recognition to amplify inflammatory cascades, contributing to the chronicity of acne lesions [

26]. Additionally, enrichment of interferon-mediated signaling and Notch signaling indicates broader immune modulation, with interferons enhancing antiviral-like responses against bacterial PAMPs and Notch regulating epidermal differentiation [

27]. Reactome and Disease Ontology (DO) analyses further linked DEGs to chromatin modification and dermatological conditions, reinforcing acne’s inflammatory nature akin to psoriasis or eczema [

28].

Experimental validation corroborated these transcriptomic insights. Morphological changes in infected HaCaT cells, including cell swelling (area: 250.08 ± 17.28 μm

2 vs. 135.78 ± 20.42 μm

2,

p < 0.0001) and irregular boundaries, indicate cytoskeletal disruption and potential apoptosis, consistent with

C. acnes IA

1–induced stress (

Table 5). Fluorescence microscopy revealed biofilm formation by

C. acnes IA

1 on keratinocyte surfaces, supporting its role in persistent infection and chronic inflammation [

10]. The significant increase in IL-6 secretion validates the transcriptomic upregulation of IL-6 signaling and aligns with hub gene functions, as HNRNPA2B1 and RBM39 regulate cytokine expression through splicing [

22]. These findings highlight IL-6 as a pivotal mediator of acne inflammation, suggesting that targeting its upstream regulators or CLR signaling could mitigate

C. acnes IA

1–induced damage. Furthermore, the cutaneous microenvironment and its extracellular matrix (ECM) components play a crucial role in modulating inflammatory responses to microbial stimuli, such as

C. acnes infection. Recent studies highlight that sulfated glycosaminoglycans (sGAGs), including artificially sulfated hyaluronan derivatives, can influence keratinocyte proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory signaling within the ECM. These modified sGAGs incorporated into collagen-based artificial ECMs have been shown to promote keratinocyte growth and regulate immune cell responses under inflammatory conditions, potentially attenuating excessive inflammation while supporting tissue homeostasis. Such ECM modifications may offer insights into how the skin barrier and microenvironment mitigate pathogen-induced keratinocyte activation in acne pathogenesis, complementing the CLR-mediated pathways identified in this study [

29,

30,

31].

Despite these advances, limitations must be acknowledged. The HaCaT cell model, while effective for studying keratinocyte responses, lacks the complexity of the in vivo skin microenvironment, which includes sebocytes, fibroblasts, and immune cells that modulate acne progression [

28]. Focusing on a single

C. acnes IA

1 strain (CICC 10864) may not capture the diversity of phylotypes contributing to acne etiology, as other phylotype strains (e.g., IA

2, IB) or clinical isolates exhibit distinct virulence profiles [

21]. Additionally, the 24-h co-culture duration may not fully reflect chronic acne dynamics, where prolonged bacterial exposure drives sustained inflammation. Future studies should incorporate multi-omics approaches, such as proteomics and metabolomics, to validate hub gene functions and explore their interactions with other skin cell types. Clinical cohorts with diverse acne severities and

C. acnes phylotypes could enhance translational relevance, while CRISPR–based gene editing of HNRNPA2B1 or RBM39 in skin models could clarify their causal roles in inflammation and comedogenesis [

32].

Our findings pave the way for microbiome-targeted therapies, such as inhibitors of CLR signaling or RNA splicing modulators, to reduce reliance on broad-spectrum antibiotics, which exacerbate resistance [

33]. For example, small-molecule inhibitors targeting HNRNPA2B1-mediated RNA processing could suppress inflammatory cytokine production, offering a precision medicine approach to acne [

34]. These results also highlight the potential of hub genes as diagnostic biomarkers, enabling early detection of severe acne phenotypes through non-invasive skin biopsies [

20]. By elucidating the molecular interplay between

C. acnes IA

1 and keratinocytes, this study advances our understanding of acne pathogenesis and supports the development of novel therapeutic strategies to improve clinical outcomes and reduce recurrence.

In light of these findings, the identified hub genes (HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPM, and RBM39) and the enriched C-type lectin receptor (CLR) signaling pathway offer promising avenues for novel therapeutic development. Targeting RNA splicing regulators such as these hub genes could inspire the design of small–molecule modulators or RNA–based therapies to attenuate inflammatory cytokine production and keratinocyte hyperproliferation in acne. Similarly, CLR pathway inhibitors may be formulated into topical agents to selectively dampen pathogen-induced inflammation without broad antimicrobial effects, reducing the risk of dysbiosis and antibiotic resistance. Beyond pharmacological targeting, biomaterial-based strategies—such as scaffolds incorporating microbiome-modulating probiotics or prebiotics—could restore skin homeostasis by promoting beneficial commensals while suppressing virulent

C. acnes strains. Looking ahead, integrating transcriptomic biomarkers from this study with predictive modeling approaches (e.g., machine learning algorithms trained on multi–omics data) holds potential for personalized topical interventions, enabling early identification of high-risk patients and tailored treatment regimens to improve efficacy and minimize recurrence [

28,

35,

36,

37,

38].