Effect of Gut Microbiota Alteration on Colorectal Cancer Progression in an In Vivo Model: Histopathological and Immunological Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Animals

2.3. Induction of Colorectal Cancer

2.4. Human Fecal Microbiota

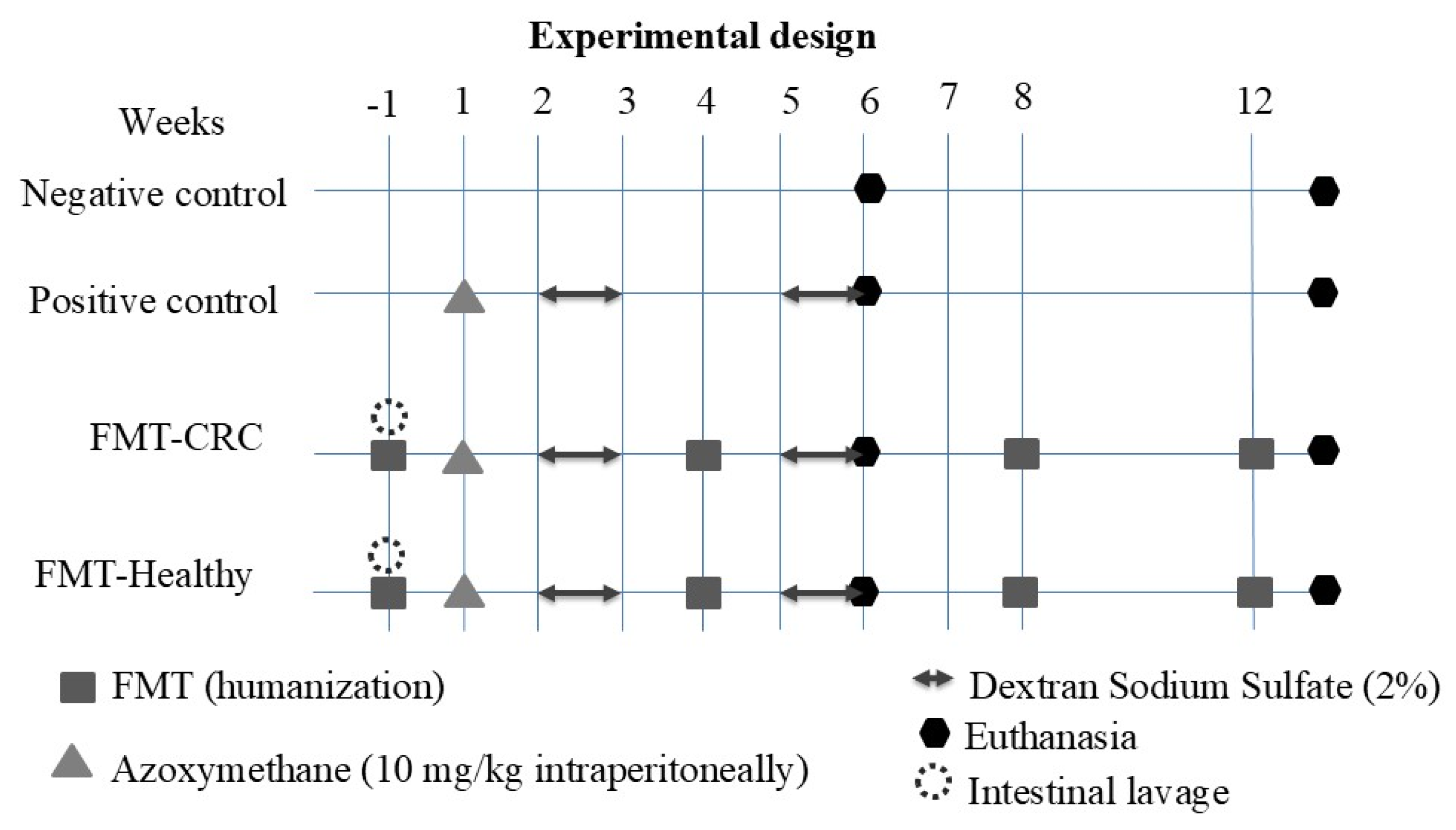

2.5. Experimental Design

2.6. Optimization and Validation of the Intestinal Cleansing Protocol and Human FMT in BALB/c Mice

2.7. Human Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Mice

2.8. Animal Euthanasia

2.9. Histopathological Analysis

2.10. Inflammatory Cytokines

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

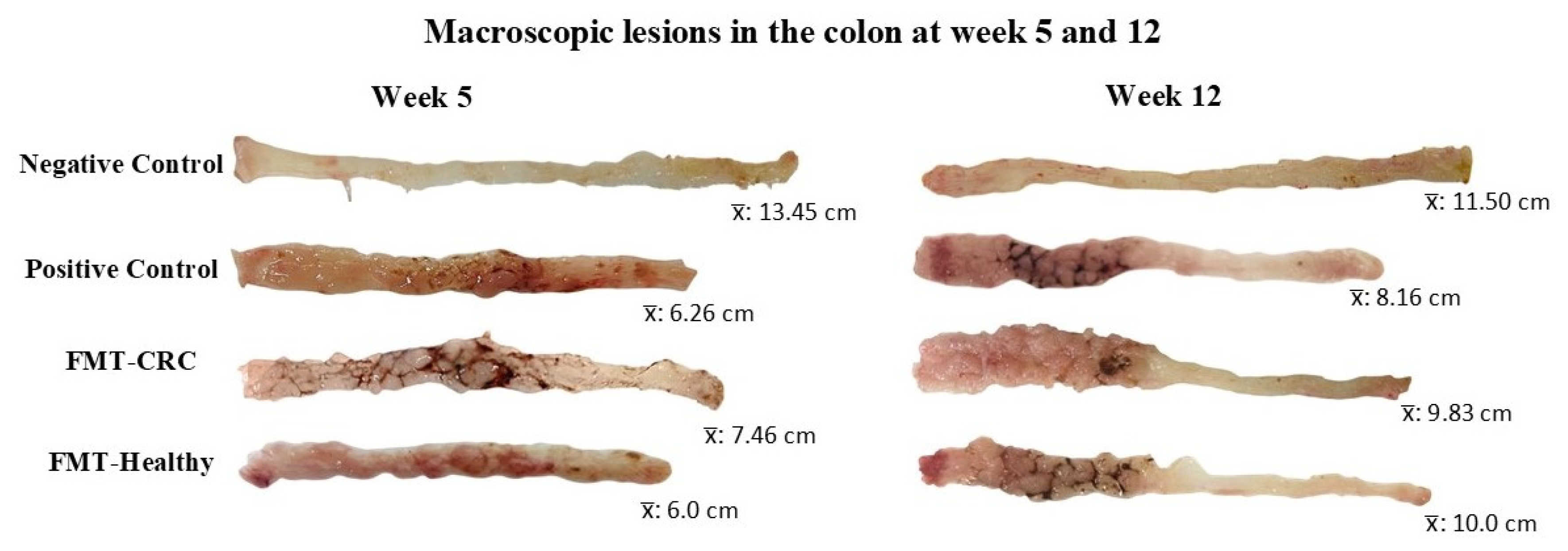

3.1. Body Weight and Intestinal Morphometry

3.2. Histopathology Evaluation

3.3. Inflammatory Cytokine Determination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOM | Azoxymethane |

| CD | Crohn’s Disease |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| DI | Clostridioides difficile Infection |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DSS | Dextran Sodium Sulfate |

| FM | Fecal Microbiota |

| FMT | Fecal Microbiota Transplantation |

| GM | Gut Microbiota |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| IL | Interleukin |

| PBS | Saline Solution Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| TNBS | 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid |

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

References

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Cancer. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. Globocan-The Global Cancer Observatory. Cancer Today. 2022. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Barani, M.; Bilal, M.; Rahdar, A.; Arshad, R.; Kumar, A.; Hamishekar, H.; Kyzas, G.Z. Nanodiagnosis and nanotreatment of colorectal cancer: An overview. J. Nanopart. Res. 2021, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiuzzi, C.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Lippi, G. Concise update on colorectal cancer epidemiology. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, E.; Sampson, J. The role of inherited genetic variants in colorectal polyposis syndromes. Adv. Genet. 2019, 103, 183–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashokkumar, P.; Divya, T.; Kumar, K.; Dineshbabu, V.; Velavan, B.; Sudhandiran, G. Colorectal carcinogenesis: Insights into the cell death and signal transduction pathways: A review. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2018, 10, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Xu, P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, T.; Ruszkowska, M.; Danielewicz, A.; Niedźwiedzka, E.; Arłukowicz, T.; Przybyłowicz, K.E. A review of colorectal cancer in terms of epidemiology, risk factors, development, symptoms and diagnosis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanegas, D.P.; Ramírez López, L.X.; Limas Solano, L.M.; Pedraza Bernal, A.M.; Monroy Díaz, A.L. Factores asociados a cáncer colorrectal. Rev. Médica Risaralda 2020, 26, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Veintimilla, D.; Frías Toral, E. Microbiota intestinal y cáncer. Rev. Nutr. Clín. Metab. 2021, 4, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvoncikova, P.; Splichalova, P.; Videnska, P.; Gardlik, R. The Human Mycobiome: Colonization, Composition and the Role in Health and Disease. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.H.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: Mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leystra, A.A.; Clapper, M.L. Gut microbiota influences experimental outcomes in mouse models of colorectal cancer. Genes 2019, 10, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galipeau, H.J.; McCarville, J.L.; Huebener, S.; Litwin, O.; Meisel, M.; Jabri, B.; Sanz, Y.; Murray, J.A.; Jordana, M.; Alaedini, A.; et al. Intestinal microbiota modulates gluten-induced immunopathology in humanized mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 2969–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Gu, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, C.; Zhong, W.; Wang, B.; Cao, H. Gut mycobiome: A promising target for colorectal cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejia-Montilla, J.; Reyna-Villasmil, N.; Bravo-Henríquez, A.; Fernández-Ramírez, A.; Reyna-Villasmil, E. Modulación de la microbiota intestinal y patogénesis de la obesidad. Av. Biomed. 2021, 10, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Brusnic, O.; Onisor, D.; Boicean, A.; Hasegan, A.; Ichim, C.; Guzun, A.; Chicea, R.; Todor, S.B.; Vintila, B.I.; Anderco, P.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Insights into Colon Carcinogenesis and Immune Regulation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Cui, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, F. The interplay of gut microbiota between donors and recipients determines the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, R.J.; Rubin, D.T. Fecal microbiota transplantation as therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2014, 8, 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Robertis, M.; Massi, E.; Poeta, M.; Carotti, S.; Morini, S.; Cecchetelli, L.; Signori, E.; Fazio, V.M. The AOM/DSS murine model for the study of colon carcinogenesis: From pathways to diagnosis and therapy studies. J. Carcinog. 2011, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parang, B.; Barrett, C.W.; Williams, C.S. AOM/DSS Model of Colitis-Associated Cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1422, 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Gao, J.; Yang, B.; Chen, X.; Kang, N.; Liu, W. Protocol for colitis-associated colorectal cancer murine model induced by AOM and DSS. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfarth, A.A.; Smith, T.M.; VanInsberghe, D.; Dunlop, A.L.; Neish, A.S.; Corwin, E.J.; Jones, R.M. A Human Microbiota-Associated Murine Model for Assessing the Impact of the Vaginal Microbiota on Pregnancy Outcomes. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 570025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzosek, L.; Ciocan, D.; Borentain, P.; Spatz, M.; Puchois, V.; Hugot, C.; Ferrere, G.; Mayeur, C.; Perlemuter, G.; Cassard, A.M. Transplantation of human microbiota into conventional mice durably reshapes the gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, E.; Rendón, J.P.; Bedoya-Betancur, V.; Montoya, J.; Duque, J.M.; Naranjo, T.W. Standardization of a Preclinical Colon Cancer Model in Male and Female BALB/c Mice: Macroscopic and Microscopic Characterization from Pre-Neoplastic to Tumoral Lesions. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.; Nakatsu, G.; Han, J.; Xu, W.; Xiao, X.; Kwong, T.N.Y.; Tsoi, H.; Wu, W.K.K.; et al. Gavage of Fecal Samples From Patients With Colorectal Cancer Promotes Intestinal Carcinogenesis in Germ-Free and Conventional Mice. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 1621–1633.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, X.; Zhong, W.; Yang, M.; Xu, M.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J.; Liu, T.; Song, X.; Dong, W.; et al. Gut microbiota from colorectal cancer patients enhances the progression of intestinal adenoma in Apcmin/+ mice. eBioMedicine 2019, 48, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Feng, Y.; Cen, R.; Hou, X.; Yu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhou, L.; Ji, Q.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. San-Wu-Huang-Qin decoction attenuates tumorigenesis and mucosal barrier impairment in the AOM/DSS model by targeting gut microbiome. Phytomedicine 2022, 98, 153966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Tao, T.; Zhang, J.; Su, A.; Zhao, L.; Chen, H.; Hu, Q. Comparison of effects on colitis-associated tumorigenesis and gut microbiota in mice between Ophiocordyceps sinensis and Cordyceps militaris. Phytomedicine 2021, 90, 153653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, K.D.; Maurya, A.K.; Ibrahim, H.; Rao, S.; Hove, P.R.; Kumar, D.; Kant, R.; Raina, B.; Agarwal, R.; Kuhn, K.A.; et al. Dietary Rice Bran-Modified Human Gut Microbial Consortia Confers Protection against Colon Carcinogenesis Following Fecal Transfaunation. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hua, W.; Li, C.; Chang, H.; Liu, R.; Ni, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Hou, M.; et al. Protective Role of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation on Colitis and Colitis-Associated Colon Cancer in Mice Is Associated With Treg Cells. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Tan, X.; Zou, H.; Feng, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; He, J.; Cui, B.; et al. Human Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Reduces the Susceptibility to Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Germ-Free Mouse Colitis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 836542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, N.; McGovern, E.; Raposo, A.; Khatiwada, S.; Shen, S.; Koentgen, S.; Hold, G.; Behary, J.; El-Omar, E.; Zekry, A. Refining a Protocol for Faecal Microbiota Engraftment in Animal Models After Successful Antibiotic-Induced Gut Decontamination. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 770017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Cao, J.; Deng, Z.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. Effect of Fiber and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Donor on Recipient Mice Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 757372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Dozier, E.A.; Glover, M.S.; Novick, S.; Ford, M.; Morehouse, C.; Warrener, P.; Caceres, C.; Hess, S.; Sellman, B.R.; et al. Engraftment of Bacteria after Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Is Dependent on Both Frequency of Dosing and Duration of Preparative Antibiotic Regimen. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Roy, T.; Debédat, J.; Marquet, F.; Da-Cunha, C.; Ichou, F.; Guerre-Millo, M.; Kapel, N.; Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Clément, K. Comparative Evaluation of Microbiota Engraftment Following Fecal Microbiota Transfer in Mice Models: Age, Kinetic and Microbial Status Matter. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnesen, H.; Müller, M.H.B.; Aleksandersen, M.; Østby, G.C.; Carlsen, H.; Paulsen, J.E.; Boysen, P. Induction of colorectal carcinogenesis in the C57BL/6J and A/J mouse strains with a reduced DSS dose in the AOM/DSS model. Lab. Anim. Res. 2021, 37, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Kwon, D.; Son, S.W.; Bin Jeong, T.; Lee, S.; Kwak, J.-H.; Cho, J.-Y.; Hwang, D.Y.; Seo, M.-S.; Kim, K.S.; et al. Inflammatory responses of C57BL/6NKorl mice to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis: Comparison between three C57BL/6 N sub-strains. Lab. Anim. Res. 2021, 37, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid-Gallegos, M.S.; Sánchez-Chino, X.M.; Álvarez-González, I.; Madrigal Bujaidar, E.; Vásquez-Garzón, V.R.; Baltiérrez Hoyos, R.; Jiménez Martínez, C. Protocol for short-term tumor development, as an option for the study of chemopreventive agents. Nova Sci. 2022, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Koh, S.J.; Radi, Z.A.; Habtezion, A. Animal models of inflammatory bowel disease: Novel experiments for revealing pathogenesis of colitis, fibrosis, and colitis-associated colon cancer. Intest. Res. 2023, 21, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar-Nuñez, M.L.; Luzardo-Ocampo, I.; Campos-Vega, R.; Gallegos-Corona, M.A.; González de Mejía, E.; Loarca-Piña, G. Physicochemical and nutraceutical properties of moringa (Moringa oleifera) leaves and their effects in an in vivo AOM/DSS-induced colorectal carcinogenesis model. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleal, M.; Sarrabayrouse, G.; Willamil, J.; Santiago, A.; Pozuelo, M.; Manichanh, C. A single faecal microbiota transplantation modulates the microbiome and improves clinical manifestations in a rat model of colitis. eBioMedicine 2019, 48, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörbe, U.M.; Jørgensen, P.B.; Fenton, T.M.; von Burg, N.; Riis, L.B.; Spencer, J.; Agace, W.W. Human gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT); diversity, structure, and function. Mucosal Immunol. 2021, 14, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Yuan, L.W.; Yang, L.C.; Zhang, Y.W.; Yao, H.C.; Peng, L.X.; Yao, B.J.; Jiang, Z.X. Role of gut microbiota in Crohn’s disease pathogenesis: Insights from fecal microbiota transplantation in mouse model. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 3689–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florescu, D.N.; Boldeanu, M.V.; Șerban, R.E.; Florescu, L.M.; Serbanescu, M.S.; Ionescu, M.; Streba, L.; Constantin, C.; Vere, C.C. Correlation of the Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, Inflammatory Markers, and Tumor Markers with the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer. Life 2023, 13, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirlekar, B. Tumor promoting roles of IL-10, TGF-β, IL-4, and IL-35: Its implications in cancer immunotherapy. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Diez, R.R.; Tejera-Muñoz, A.; Orejudo, M.; Marquez-Exposito, L.; Santos, L.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Cantero-Navarro, E.; Tejedor-Santamaria, L.; Marchant, V.; Ortiz, A.; et al. Interleuquina-17A: Posible mediador y diana terapéutica en la hipertensión. Nefrología 2021, 41, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrello, C.; Garavaglia, F.; Cribiù, F.M.; Ercoli, G.; Lopez, G.; Troisi, J.; Colucci, A.; Guglietta, S.; Carloni, S.; Guglielmetti, S.; et al. Therapeutic faecal microbiota transplantation controls intestinal inflammation through IL10 secretion by immune cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moynihan, K.D.; Kumar, M.P.; Sultan, H.; Pappas, D.C.; Park, T.; Chin, S.M.; Bessette, P.; Lan, R.Y.; Nguyen, H.C.; Mathewson, N.D.; et al. IL2 Targeted to CD8+ T Cells Promotes Robust Effector T-cell Responses and Potent Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1206–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, X.; Liu, P.; Ge, W.; Hu, L.; Zuo, Z.; Xiao, H.; Liao, W. Treatment and mechanism of fecal microbiota transplantation in mice with experimentally induced ulcerative colitis. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 246, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancione, M.; Giordano, G.; Remo, A.; Febbraro, A.; Sabatino, L.; Manfrin, E.; Ceccarelli, M.; Colantuoni, V. Immune escape mechanisms in colorectal cancer pathogenesis and liver metastasis. J. Immunol. Res. 2014, 2014, 686879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas Valverde, C.A.; Ramírez Pérez, D. Las células Treg en la inmunoedición e inflamación asociada al cáncer. Rev. Fac. Med. 2015, 58, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.L.; Lu, L.; Wang, X.S.; Qin, L.Y.; Wang, P.; Qiu, S.P.; Wu, H.; Huang, F.; Zhang, B.B.; Shi, H.L.; et al. Alteration of gut microbiota and inflammatory cytokine/chemokine profiles in 5-fluorouracil induced intestinal mucositis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Incognito, D.; Ciappina, G.; Gelsomino, C.; Picone, A.; Consolo, P.; Scano, A.; Franchina, T.; Maurea, N.; Quagliariello, V.; Berretta, S.; et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer: Relationship Among Immune Modulation, Potential Biomarkers and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scano, A.; Fais, S.; Ciappina, G.; Genovese, M.; Granata, B.; Montopoli, M.; Consolo, P.; Carroccio, P.; Muscolino, P.; Ottaiano, A.; et al. Oxidative Stress by H2O2 as a Potential Inductor in the Switch from Commensal to Pathogen in Oncogenic Bacterium Fusobacterium nucleatum. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.; Armet, A.M.; Finlay, B.B.; Shanahan, F. Establishing or Exaggerating Causality for the Gut Microbiome: Lessons from Human Microbiota-Associated Rodents. Cell 2020, 180, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Mouse Strain | Age | Model | Microbiota Depletion | TMI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Frequency | Duration | Dose | Frequency | Duration | ||||

| [26] | C57BL/6 | 6 weeks | AOM | AB | Diary | 2 weeks | 200 μL (1 g/5 mL) | 2 t/week | 5 weeks |

| [27] | C57BL/6J | 4 weeks | Apc min/+ | AB | Diary | 3 d | 200 μL (1 g/5 mL) | 1 t/d | 1 week |

| 3 t/week | 2 weeks | ||||||||

| 1 t/week | 3–8 weeks | ||||||||

| [28] | C57BL/6J | 5 weeks | AOM/DSS | AB | - | 4 weeks | 200 μL | 3 t/week | Sacrifice (84 days) |

| [29] | C57BL/6 | 5 weeks | AOM/DSS | AB | - | 4 weeks | - | Diary | 12 weeks |

| [30] | C57BL/6 (GF) | 8–10 weeks | AOM/DSS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 200 μL | Days 1 and 5 | N/A |

| [31] | Balb/c | 6 weeks | AOM/DSS | - | - | - | 200 μL | Days 14, 35 and 56 | N/A |

| [32] | Balb/c (GF) | 8–10 weeks | DSS | N/A | N/A | N/A | 100 μL | Diary | 7 days |

| [33] | C57BL/6J | 4 weeks | N/A | AB | Diary | 21 d | 200 μL (0.1 g/L) | 1 t/week | 3 weeks |

| [34] | ICR | 8 weeks | N/A | AB | - | 2 weeks | 200 μL (1 g/mL) | Diary | 14 days |

| [35] | Balb/c | 6 weeks | N/A | AB + PEG | Diary | 3 d + 12 h PEG (10%) | 200 μL (10 mg/mL) | 1 dose | - |

| 3 weeks (Cycles 5/2 d) | 5 doses | ||||||||

| [36] | C57BL/6J | 3 weeks | N/A | AB + PEG | Diary | 7 d + PEG (1 h later) | 200 μL | Diary | 3 days |

| C57BL/6J (GF) | 8 weeks | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| [24] | C57BL/6J | 8 weeks | N/A | PEG | 20 min | 1–6 doses | - | 2 t/week | 4 weeks |

| 1 t/week | 4 weeks | ||||||||

| 2 t/week | 1 week | ||||||||

| 1 t/week | 1 week | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Montoya Montoya, J.; Gómez, E.C.; Tabares Guevara, J.H.; Arango Rincón, J.C.; Naranjo Preciado, T.W. Effect of Gut Microbiota Alteration on Colorectal Cancer Progression in an In Vivo Model: Histopathological and Immunological Evaluation. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010015

Montoya Montoya J, Gómez EC, Tabares Guevara JH, Arango Rincón JC, Naranjo Preciado TW. Effect of Gut Microbiota Alteration on Colorectal Cancer Progression in an In Vivo Model: Histopathological and Immunological Evaluation. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontoya Montoya, Juliana, Elizabeth Correa Gómez, Jorge Humberto Tabares Guevara, Julián Camilo Arango Rincón, and Tonny Williams Naranjo Preciado. 2026. "Effect of Gut Microbiota Alteration on Colorectal Cancer Progression in an In Vivo Model: Histopathological and Immunological Evaluation" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010015

APA StyleMontoya Montoya, J., Gómez, E. C., Tabares Guevara, J. H., Arango Rincón, J. C., & Naranjo Preciado, T. W. (2026). Effect of Gut Microbiota Alteration on Colorectal Cancer Progression in an In Vivo Model: Histopathological and Immunological Evaluation. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010015