Abstract

Background/Objectives: Fabry disease is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder. It is characterised by impaired metabolism of glycosphingolipids whose accumulation causes irreversible organ damage and life-threatening complications. Genotype–phenotype correlations have a limited scope in Fabry disease as the disorder presents with wide-ranging clinical variability. In other X-linked disorders, epigenetic profiling has identified methylation patterns and disease modifiers that may explain clinical heterogeneity. In this narrative review and thematic analysis, the role of DNA methylation and epigenetics on the clinical phenotype in Fabry disease was investigated. Methods: Embase, PubMed, and PsycINFO were searched to identify literature on DNA methylation and epigenetics in Fabry disease. Based on the eligibility criteria, 20 articles were identified, and a thematic analysis was performed on the extracted data to identify themes. Results: Three themes emerged: (I) genetic modifiers, (II) methylation profiling, and (III) insights into X chromosome inactivation (XCI). The evidence synthesis revealed that telomere length, especially in early disease stages, bidirectional promoter (BDP) methylation by sphingolipids, epigenetic reader proteins, mitochondrial DNA haplogroups, and DNA methylation of the promoter region of the calcitonin receptor gene are potential genetic modifiers in Fabry disease. Methylation patterns also reveal episignatures in Fabry disease evolution and genes implicated in the maintenance of basement membranes. Studies on XCI further emphasise disease heterogeneity and draw attention to methodological issues in the assessment of XCI. Conclusions: This thematic review shows that DNA methylation and genetic modifiers are key factors modifying clinical variability in Fabry disease. More broadly, it underscores a crucial role for epigenetic processes in driving disease onset, progression, and severity in X-linked disorders.

1. Introduction

The X chromosome has more than 1000 genes essential to biological functions [1]. To prevent the deleterious consequences of a double dose of X-linked genes, early during embryogenesis, the X chromosome is randomly inactivated in humans. This epigenetic process is known as X chromosome inactivation (XCI) [2,3]. Consequently, XCI results in a random ‘mosaic’ pattern of active and inactive X chromosomes in cells throughout the body [1]. The inactive X chromosome exhibits increased levels of DNA methylation and histone modifications [4]. During the process of XCI, several hundred genes are silenced [5]. The implications of XCI have long been recognised in neurological diseases [6], but it can also assist in the identification of X-linked disease carriers [7]. Skewing (or the XCI ratio) occurs when one X chromosome is preferentially inactivated over the other and can happen in neurotypical females [8]. Theoretically, XCI ratios can range from a 0:100 to a 50:50 ratio [9]. Objective evidence has indicated that only a small number of neurotypical females show skewed patterns [9]. The clinical significance of skewing in neurotypical females is unclear, and those with highly skewed patterns may warrant further attention [9]. The XCI pattern can influence disease manifestation, especially when the mosaic pattern is skewed. In X-linked disorders, a skewed XCI pattern has clinical importance and confers a selective advantage to cells, especially when the X chromosome containing the mutated gene is inactivated.

There are more than 141 disorders associated with intellectual disability due to pathogenic variants on the X chromosome [10]. One such disorder is Rett syndrome (RTT) (OMIM #312750), a debilitating X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder. In RTT, skewing was observed in 36% (n = 45/125) in individuals with classical RTT [11,12]. Because the pathogenic variant (methyl-CpG binding protein 2, MECP2) responsible for most cases of classical RTT is located on the X chromosome, it implies that XCI could theoretically regulate the clinical severity of RTT. However, the impact of XCI upon disease severity in RTT is unclear. Evidence suggests that XCI in RTT does not influence clinical severity [12,13], while others suggest a correlation [14]. More recent research suggests that XCI has a minor impact on disease severity in those with severe MECP2 pathogenic variants [15]. In Fabry disease (OMIM #301500), the mutated gene, alpha-galactosidase A (GLA), is also found on the X chromosome (Xq21.3-q22) [16]. The GLA gene encodes a lysosomal alpha-galactosidase A (α-GAL A) enzyme that is involved in the metabolism of glycosphingolipids, usually globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and its deacetylated form (Lyso-Gb3). Enzyme deficiency causes a build-up of these glycosphingolipids in lysosomes, leading to systemic disease. More than 1000 pathogenic variants have been identified in the GLA gene [17], and the clinical phenotype depends upon the disease trajectory, i.e., classic and later onset forms, the type of GLA variant, gender, age, and the amount of α-Gal A activity [18].

Although Fabry disease is a metabolic disorder and RTT is a neurodevelopmental disorder, both disorders share commonalities. First, the build-up of Gb3 and Lyso-Gb3 deposits activates pro-inflammatory pathways and induces oxidative stress in Fabry disease [19,20]. This inflammatory burden is also mirrored in RTT, where individuals exist in a subclinical chronic inflammatory state [21]. Second, males are more severely impacted in Fabry disease [16]. While RTT predominantly affects females, it has also been identified in males with variable clinical presentation ranging from mild to severe [22]. Third, both Fabry disease and RTT have multi-organ involvement and are susceptible to life-threatening neurological complications [22,23], and fourth, both are characterised by genotype–phenotype heterogeneity. Indeed, RTT remains a clinical diagnosis [24], and genetic modifiers in RTT can influence disease progression [25,26]. Dysregulated methylation is a hallmark feature of RTT [27,28,29].

Skewing may occur through various mechanisms [30], including changes in DNA methylation [31]. The methylation status of the androgen receptor is the gold standard method for determining the XCI pattern [32]. Ultra-deep methylation analyses could help to facilitate our understanding of disease predisposition in X-linked disorders, especially in females with Fabry disease [33], where disease onset and clinical phenotype are more variable [34,35]. Nevertheless, little emphasis has been put on how dysregulated methylation may contribute to disease phenotype in Fabry.

Aim of the Narrative Review

Given the clinical heterogeneity of Fabry disease and its association with DNA methylation, it would be essential to examine how changes in the Fabry epigenome influence the clinical profile of individuals. This notion is also shared by others who have suggested that DNA methylation may play a role in influencing the variability of the clinical phenotype in hemizygous and heterozygous Fabry disease [16]. Furthermore, because the clinical phenotype in Fabry disease individuals cannot be explained entirely by skewed XCI patterns, it would be sensible to consider other elements that could have a role, such as genetic modifiers of disease severity, as noted for other X-linked disorders [25,36,37]. The overarching aim of the present review was, therefore, to answer the following research question: What is the role of DNA methylation and genetic modifiers on the clinical phenotype in Fabry disease? To answer this question, the study reviewed the literature on methylation studies in Fabry disease. It had the following objectives:

- (I)

- To evaluate studies of DNA methylation in Fabry disease.

- (II)

- To perform a thematic analysis and identify themes that lead to a better understanding of clinical severity and disease prediction.

- (III)

- To determine whether areas emerging from the thematic analysis can be applied to other X-linked disorders.

2. Methods

2.1. Narrative Review Strategy

The structure of this narrative review was guided by a 12-step framework described in Kable et al. (2012) [38]. This framework is a step-by-step guide to undertake reviews and was recently adopted in a narrative review of communication abilities in RTT [39]. Considering this, the 12-step framework was used to improve the methodological rigour of the current review. In line with others [39], the current narrative review also adopted the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) [40]. The SANRA is a scale for the quality appraisal of narrative reviews. It has the following six items: (I) justification of the review’s importance, (II) aims of the review, (III) description of the search, (IV) supporting references, (V) scientific reasoning, and (VI) presentation of data. The SANRA can be used as a self-assessment measure to ensure the robustness and improve the quality of narrative reviews [40]. There are no consensus guidelines for conducting narrative reviews; however, the SANRA criteria have been employed previously to enhance the quality and reliability of a narrative review [39]. Similarly, to improve the robustness of the evidence synthesis, the method of this narrative review was assessed against the SANRA criteria. The SANRA evaluation of the study is presented in Supplementary Table S1.

While this current narrative review did not follow the guidelines adopted for comprehensive systematic reviews, it did utilise aspects from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [41] to screen and identify eligible articles as previously described [42]. The Embase, PubMed, and PsycINFO databases were searched in August 2025 with the age date filter restricted to the last 10 years (2015). Boolean operators and the truncation symbol (*) were used in the search. The ‘snowballing’ approach, which involves examining the reference sections of articles, was also used to identify any other relevant articles.

2.2. Search Terms

The following search terms were used:

((Fabry disease) OR (Fabry’s disease) OR (alpha-galactosidase A deficiency*) OR (Anderson-Fabry disease)) AND ((methylation) OR (DNA) OR (methylome) OR (epigenome) OR (epigenetic*) OR (Histone modification*)).

2.3. Population Characteristics

The database searches focused exclusively on studies performed in individuals with Fabry disease, specifically on methylation or aspects related to methylation, such as histone modification.

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria are as follows:

- ➢

- Peer-reviewed full-text articles in the English language.

- ➢

- Participants with a diagnosis of Fabry disease. This can also include studies performed on cell lines derived from individuals with Fabry.

- ➢

- The study included articles from 2015 to August 2025.

Exclusion criteria are as follows:

- ➢

- Studies performed exclusively using animal models.

- ➢

- Book chapters, conference abstracts, meta-analyses, preprints, protocols, and all types of review articles.

2.5. Extraction of Data

The following data were extracted from the eligible articles and documented in a table: sample size, study purpose, participant characteristics, methods used for assessing methylation, and summary of the key findings. Data extraction was performed by the lead author (J.S.). When the data had been extracted into a summary table, it was reviewed by the third author (U.R.). Any issues were resolved before the table of extracted data was finalised.

2.6. Thematic Analysis Procedure

Following data extraction, a thematic analysis was performed by the first author (J.S.). The thematic analysis framework was reviewed by another author (U.R.), and a consensus was reached before the framework was approved. The thematic analysis approach used the exemplar described in Naeem et al. (2023) [43], which followed a structured approach: (I) select statements, (II) choose keywords, (III) perform coding, and (IV) generate themes.

- (I)

- Selection of Statements

In this process, a grounded-theory approach was used as a recognised method for identifying themes directly from data [44]. Statements were extracted from the 20 studies with the aim of identifying keywords.

- (II)

- Keywords

This process enhances the methodical rigour of the thematic analysis, as the selection of keywords from statements improves the conceptualisation stage of the analysis [43]. Colour was used in the statements to select keywords that identified essential concepts from the studies, guided by the 6Rs selection of keywords of thematic analysis in complex datasets [43].

- (III)

- Inductive Coding

Coding was performed manually by J.S. to capture the essential attributes of the data relevant to the research question ‘What is the role of DNA methylation and genetic modifiers on the clinical phenotype in Fabry Disease?’ By examining the interconnection and patterns between the keywords, succinct words/terms (codes) were formulated and categorised to identify patterns in the data. This process of inductive coding is data-driven, allowing themes to emerge from the data [45].

- (IV)

- Generation of Themes

Codes were grouped into meaningful themes that linked the research question to the data. The 4Rs framework, consisting of ‘reciprocal, ‘recognisable’, ‘responsive’, and ‘resourceful’, as described in Naeem et al. (2023) [43], was used to assist in the identification of themes. The frequency of each theme was summarised in Microsoft Excel.

The thematic analysis framework used in this study to identify the themes is described in Supplementary Table S2.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

To cover as much of the literature as possible related to methylation, the words methylome, epigenome, epigenetic, and histone modification were added to make the search as expansive as possible. Following a search of three databases (Embase, PubMed, and PsycINFO), the titles and abstracts of 567 articles were screened. When assessed for eligibility, 549 records were excluded (425 from Embase, 121 from PubMed, and 3 from PsychINFO), and 18 articles met the eligibility criteria. An additional two articles were included following a ‘snowball’ search, and in total, 20 articles were included and analysed (Figure 1 and Table 1). Three studies were case reports that reported on Fabry patients with unique clinical presentations [46,47,48]. A severe phenotype was observed in a female with associated 10q26 deletion syndrome [46]. Males usually have a more severe presentation; however, a late-onset male patient with residual α-galactosidase activity but milder organ involvement was reported [47]. A further case identified a new pathogenic variant (c.270C>G [p.Cys90Trp]) in Fabry disease [48]. These cases highlight the clinical complexity of Fabry disease in hemizygous and heterozygous individuals. The sample size of other studies ranged from 4 [49] to 510 individuals [50]. Two studies used fibroblast or endothelial cell lines derived from individuals with Fabry disease to investigate autophagy [51] and DNA methylation patterns [52]. A range of assessment methods was used for evaluating XCI and DNA methylation patterns. These included studies that used the Human Androgen Receptor (HUMARA) test [53,54,55] to bisulfite treatment [46,52,56]. The FAbry STabilisation indEX (FASTEX) is a tool used to assess clinical severity in Fabry disease [57]. Two studies have assessed clinical severity using FASTEX [54,58]. Another used the Mainz Severity Score Index (MSSI) and the Fabry disease severity scoring system to assess changes in clinical severity [59].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the search.

The studies exhibited heterogeneity across multiple domains. The design of the studies varied from case reports to cross-sectional and observational studies. While most studies included human subjects, some also utilised cell lines derived from individuals with Fabry disease [51,52]. Studies also demonstrated methodological variation when assessing clinical severity. The FASTEX score was used in two studies [54,58], while another used the MSSI and the Fabry disease severity scoring system [59]. Different research methods were used, including haplogroup typing of mitochondrial DNA [60] or sequencing and enzyme assays for phenotype classification [61]. Outcome heterogeneity was also evidenced from studies examining methylation status [62], telomere length [63], inflammatory gene expression [64], and XCI patterns [65,66].

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Source | N (Fabry) | Study Purpose | Sample Characteristics | Relevant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] Hossain et al. (2017) | 1 | Reports on a severe and unique clinical presentation of a female patient with Fabry disease |

|

|

| [47] Bae et al. (2020) | 1 | Case of a male Fabry patient with a de novo somatic mosaicism with mild symptoms but classic GLA variant |

|

|

| [48] Čerkauskaitė et al. (2019) | ¥ 4 | Identification of the novel GLA gene mutation in a female with Fabry disease |

|

|

| [49] Al-Obaide et al. (2022) | 4 | Investigating the cumulative effects of GLA mutation and BDP methylation on disease severity |

|

|

| [50] Sezer & Ceylaner (2021) | 510 | Genetic management algorithm for high-risk patients with Fabry disease |

|

|

| [51] Yanagisawa et al. (2019) | Ψ N/A | To assess whether GLA expression levels were associated with autophagy | Fibroblasts were obtained from a female patient severely affected with Fabry disease and two siblings (sisters) who had mild symptoms |

|

| [52] Shen et al. (2022) | N/A | Investigating whether dysregulated DNA methylation has a role in the development of Fabry disease | Endothelial cell line from a patient with Fabry disease (R112H mutation, aged 64 years) |

|

| [53] Iza et al. (2025) | 7 | To examine the relationship between methylation and clinical disease in females with Fabry disease |

|

|

| [54] Rossanti et al. (2021) | 9 | Examining whether the existence of skewed XCI in females with heterozygous pathogenic variants in the GLA gene affects the phenotype |

|

|

| [55] Juchniewicz et al. (2018) | 12 | Analyze XCI patterns and examine their role in disease manifestation in female patients with Fabry disease |

|

|

| [56] Hübner et al. (2015) | 9 | A retrospective investigation of DNA methylation of the promoter region of the calcitonin receptor gene in Fabry patients |

|

|

| [58] Hossain et al. (2019) | 36 | To evaluate 36 heterozygous Fabry disease females using methylation studies of the GLA gene |

|

|

| [59] Echevarria et al. (2016) | 56 | To further understand the role of XCI in the clinical presentation in heterozygous females with Fabry disease |

|

|

| [60] Simoncini et al. (2016) | 77 | To investigate whether genetic polymorphisms in the mitochondrial genome could behave as disease modifiers in patients with Fabry disease |

|

|

| [61] Pan et al. (2016) | 73 | Evaluation of genotype–phenotype relationships in Fabry disease patients |

|

|

| [62] Di Risi et al. (2022) | 5 | Investigating methylation profiles in Fabry patients |

|

|

| [63] Levstek et al. (2024) | 99 | Assessment of telomere length in patients with Fabry disease |

|

|

| [64] Fu et al. (2022) | 8 | Examination of apabetalone treatment on inflammatory burden in cells isolated from Fabry patients treated with ERT |

|

|

| [65] Wagenhäuser et al. (2022) | 154 | Association of XCI with clinical phenotype |

|

|

| [66] Řeboun et al. (2022) | 35 | To assess the impact of XCI on the phenotype of Fabry disease patients by examining pitfalls in XCI testing |

|

|

Notes: ¥ The clinical case presentation described a 49-year-old woman with suspected Fabry disease. Ψ Fibroblasts were derived from patients with Fabry disease. Abbreviations: BDP (bidirectional promoter); CpG (cytosine–guanine dinucleotide); DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid); DS3 (Fabry disease severity scoring system); ERT (enzyme replacement therapy); FASTEX (FAbry STabilisation indEX); GAL (α-galactosidase A); Gb3 (globotriaosylceramide); GLA (alpha-galactosidase A) gene; HUMARA (Human Androgen Receptor); MSSI (Mainz Severity Score Index); RNA (Ribonucleic Acid); SD (Standard Deviation); XCI (X—chromosome inactivation).

3.2. Thematic Analysis

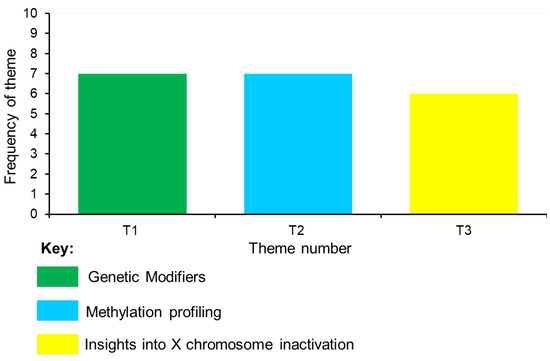

A thematic analysis was performed on the data from the 20 identified articles. This enabled the generation of meaningful themes from the extracted data. Selecting keywords derived from the data led to the identification of eightcodes and their interconnections: (1) disease expression and modifying factors, (2) molecular mediators, (3) methylation patterns, (4) genetic pathways for management, (5) biochemical pathology, (6) epigenetic regulation, (7) XCI patterns and mechanisms, and (8) clinical severity (Supplementary Table S2). These codes led to the emergence of three main themes: (I) ‘genetic modifiers’, (II) ‘methylation profiling’, and (III) ‘insights into X chromosome inactivation’. Themes 1 and 2 had the highest frequency, emerging from seven studies. Theme (III) had the lowest frequency, emerging from six studies (Figure 2). Each of the themes is described in the next section.

Figure 2.

Frequency of themes.

- Theme I: Genetic Modifiers

This theme emerged from seven studies that examined how methylation can influence disease severity. Fabry disease is thought to be associated with premature ageing [67]. One study investigated whether telomere length could have a role in predicting the clinical course of Fabry disease in 99 male and female individuals (mean age: 47.3 years) [63]. The study revealed no association between telomere length and disease stage. However, examination of telomere length may be more significant in early childhood and serve as a marker for monitoring disease progression during the initial stages of the disease [63]. In another study, the accumulative effects of bidirectional promoter (BDP) methylation levels alongside GLA mutations were associated with disease outcomes in Fabry individuals [49]. The BDP has regions susceptible to DNA methylation, which has a vital role in the expression of GLA loci. The authors demonstrated that DNA methylation of the BDP potentially caused by sphingolipids can influence disease manifestations. This study supports the premise that Fabry disease may not be solely due to GLA pathogenic variants, and other genetic modifications could play an important role. Inflammatory burden is prominent in Fabry disease, and one study demonstrated that the inhibition of epigenetic reader proteins can counteract this inflammation in individuals on enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) [64]. De novo somatic mosaicism was suggested to be a disease modifier in a 34-year-old male patient with late-onset Fabry disease with a classical GLA mutation and mild organ involvement [47]. Late-onset male patients with residual α-galactosidase activity present later, usually with cardiac and renal organ involvement [68].

When evaluating the genotype–phenotype relationship in Fabry disease, other evidence has shown that while α-GAL A activity may be associated with clinical phenotypes in female patients, the authors found no association between α-GAL A activity and genotype–phenotype relationships in male patients [61]. This study showed that in males, ocular activity was statistically associated with α-GAL A activity but not with genotype or clinical phenotypes. The study also demonstrated phenotypic variation in males from the same family and suggested that other disease modifiers (non-genetic or genetic) could influence the clinical phenotype in males with Fabry disease. Somatic mosaicism has been reported as a disease modifier in males with Fabry disease [69].

Examination of the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) in 77 individuals with Fabry disease (35 male and 42 female) revealed that specific variants in mtDNA were more prevalent in individuals with Fabry disease when compared to neurotypical controls [60]. In particular, the study showed a disproportionate distribution of haplogroups H and I and cluster HV in individuals with Fabry disease. However, there was no association with gender, age of onset, or organ involvement. Nevertheless, the authors suggested that mtDNA haplogroups may have an important role in regulating oxidative stress in Fabry disease and warrant further investigation. Finally, a retrospective investigation of DNA methylation in the promoter region of the calcitonin receptor gene suggested that aberrant methylation of this gene could potentially serve as an epigenetic biomarker in individuals with Fabry disease on ERT [56].

- Summary of Theme

From a clinical perspective, this theme highlights some important points. Reduction in telomere length has been associated with ageing [70]. A previous study has shown that telomere length is reduced in males with Fabry disease [67]. However, when viewed together with other studies, it appears that telomere length is not a reliable indicator of disease progression but may be more important during earlier disease stages [63]. Methylation of the BDP underscores the notion that Fabry disease may be influenced beyond pathogenic GLA variants. Mitochondrial DNA variants underscore the need for further research into the role of dysregulation in the mitochondrial epigenome in the pathogenesis of Fabry disease [60]. More recent evidence has shown that mitochondrial-related microRNAs (mitomiRs) are impaired in individuals with Fabry disease [71]. In biological samples derived from 63 individuals (mean age: 37 years, males: 45.6%), this study demonstrates that dysregulation in mitomiRs can affect oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial metabolism, and mitochondrial apoptosis, highlighting the essential role of mitomiRs as potential disease biomarkers in Fabry disease. When taken together, these findings suggest a critical role for mitochondrial dysregulation in the pathophysiology of Fabry disease [60,71]. In individuals on ERT, the inhibition of epigenetic reader proteins can reduce the inflammatory burden. Methylation at −78,504 CpG of the calcitonin receptor gene indicates its role as a modifier of pain suppression in Fabry disease [56]. However, the role of epigenetic reader proteins and −78,504 CpG methylation would also need to be validated in individuals pre-ERT to further substantiate their role as genetic modifiers of Fabry disease.

- Theme II: Methylation Profiling

Methylation profiling emerged from seven studies describing evidence of gene methylation and its potential association with clinical severity in Fabry disease. Using DNA methylome analysis, the methylation status of approximately 850,000 CpG sites was investigated in five males with Fabry disease with identical GLA variants [62]. This study showed that certain genes were hypermethylated in males with Fabry disease, particularly the zinc finger protein gene (ZFP57), which plays a role in methylation at imprinting regions. This proof-of-concept study suggests that the episignatures of specific genes in Fabry disease could help better understand how methylation affects Fabry disease severity. In a study using endothelial cell lines derived from a 64-year-old male with Fabry disease, 15 signaling pathways were identified that could be more prone to methylation, alongside 21 genes with differential methylation profiles [52]. Decreased methylation was associated with the upregulation of two genes, namely, collagen type IV alpha 1 (COL4A1) and alpha 2 (COL4A2) genes [52]. Interestingly, this study showed that methionine levels were also increased in both human and animal tissues, which adds weight to the premise for a dysregulated methionine cycle in Fabry disease. Dysregulated methylation patterns could be crucial in predicting disease progression, particularly during early stages of diagnosis. Others have proposed a genetic algorithm that could facilitate early diagnosis, reaffirming the importance of early disease detection [50].

Methylation studies of the GLA gene can also provide insights into the disease. In 36 heterozygous females with Fabry disease, methylation-sensitive regions within the GLA gene were identified [58]. It would also be important to probe other areas of the GLA gene, especially when novel mutations emerge. One study identified a novel mutation (c.270C>G [p. Cys90Trp]) in the GLA gene [48] with predominant cardiac involvement. It would be helpful to examine the episignatures of this novel mutation in Fabry disease to determine whether methylation could predict the evolution of Fabry disease, particularly in cases of predominant cardiac involvement. This could be more important in males with Fabry disease who have a higher frequency of cardiovascular events, such as left ventricular hypertrophy, than females (53% versus 33%) [72]. Dysregulated methylation of the GLA gene was also shown to be associated with impairment of autophagy in Fabry disease [51]. The study showed that autophagy was abnormal in a female individual with severe disease, whereas the two sisters, who had mild symptoms, exhibited normal autophagic flux. Methylation profiling can reveal additional insights into disease trajectory, with methylation of the GLA gene associated with disease severity [46]. In this study, the affected female was found to have complete methylation of the non-mutated allele that contributed to early disease onset and a severe phenotype, in comparison to her sisters, whose alleles were non-methylated. When viewed all together, these studies show that methylation profiling could provide valuable insights into disease evolution and severity.

- Summary of Theme

The evidence from the themes strongly supports a role for methylation profiling as a biomarker for disease severity. Methylation changes in genes such as COL4A, GLA, and ZFP57 allow for the development of Fabry-specific episignatures. In other disorders, such as childhood-onset dystonia and Kabuki syndrome type 1, abnormal methylation profiles in the lysine methyl transferase 2B (KMT2B) gene can improve diagnostic accuracy [73]. In Fabry disease, abnormal DNA methylation patterns (episignatures) could help (I) to risk-stratify individuals depending on organ involvement, i.e., cardiac, renal, or (II) complement genetic testing, especially in heterozygous females or those with novel variants. However, further research in larger sample sizes would be required for a role of episignatures in improving diagnosis in Fabry disease. A recent evaluation of 16 episignatures in 10 neurodevelopmental disorders demonstrated that in the diagnostic setting, some episignatures may perform better than others [74]. The authors proposed that it would be prudent to examine regions that may escape from signatures [74]. This could have clinical relevance for Fabry disease because some genes may also escape XCI [30,75], leading to variability in episignatures. Theme I revealed that mitochondria are essential players in the pathophysiology of Fabry disease. In this theme, a study showed that abnormal methylation of the GLA gene can disrupt autophagy in Fabry disease [51]. Autophagy helps to remove dysfunctional mitochondria [76]. When viewed together, dysregulated autophagy and impaired mitochondrial homeostasis may synergistically contribute to disease severity. Dysregulated autophagy can lead to the poor clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria, and this may cause further cellular injury.

- Theme III: Insights into X chromosome inactivation

Like most other lysosomal storage diseases, Fabry disease has incomplete genotype–phenotype correlations. Not only has clinical variability been noted for individuals within the same family, but it has also been noted for those from unrelated families with the same pathogenic variant [77]. Studies investigating XCI emerged from six studies. In one study, no correlation was found between XCI and clinical severity scores in females with Fabry disease [53], and the notion that XCI patterns cannot completely explain clinical severity in Fabry disease was also demonstrated by others [54,55]. However, one study from this review showed that XCI may explain the clinical variability in females with Fabry disease [59]. Others have suggested that XCI patterns have limited use in understanding disease severity in females with Fabry disease, especially when examining XCI in biological samples unaffected by disease [65]. This aspect was also considered in another study, which suggested that tissue-specific and age-related XCI patterns are important factors when interpreting studies of XCI in Fabry disease [66]. This work also recommends using a variety of XCI assays to help minimise potential bias in the interpretation of XCI studies in Fabry disease.

- Summary of Theme

The findings from this theme illustrate the complexity of unravelling the clinical variability in Fabry disease. The results from XCI studies are inconsistent, and sampling bias in assays used to measure XCI patterns in blood or buccal tissue may be a contributing factor to this inconsistency. Patterns in blood or buccal tissue may not necessarily reflect the XCI patterns in organs affected in Fabry disease. To circumvent this issue, transcriptome and exome sequencing data from blood offer another method to accurately measure XCI status and skewing [78]. Although new methods may help further our understanding of the complex interplay between XCI and clinical variability in Fabry disease, they still may not offer a complete explanation. While XCI may play a role in explaining some of the variability, it is likely that other epigenetic factors also significantly influence disease manifestations in individuals.

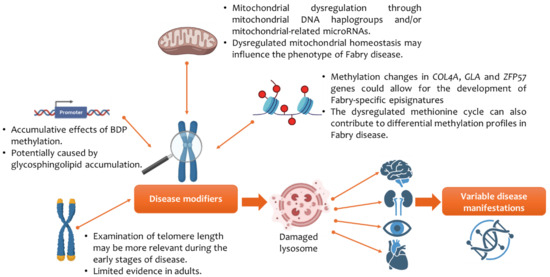

4. Discussion

According to the literature, this is the first narrative review and thematic analysis of studies examining methylation in Fabry disease. Three themes emerged that can help further our understanding of the clinical manifestations of Fabry disease. The thematic analysis showed that (I) telomere length, especially in early disease stages, (II) BDP methylation by sphingolipids, (III) epigenetic reader proteins, (III) mtDNA haplogroups H and I and cluster HV, and (IV) DNA methylation of the promoter region of the calcitonin receptor gene in individuals on ERT could potentially function as molecular mediators of clinical variability in Fabry disease and is summarised in Figure 3. Although these molecular mediators play a role in influencing the clinical phenotype in Fabry disease, the findings are associative in nature and should be interpreted with caution. Given the small and heterogeneous cohorts, the lack of replication of studies, and variability in methods, the translational evidence of the findings should be tempered, and we are unable to confirm whether one molecular mediator is more important than the other in driving clinical variability. Further research in multicentre, longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes would be needed to confirm whether molecular mediators, such as genetic modifiers and/or DNA methylation, could be used as reliable clinical epigenetic biomarkers in individuals with Fabry disease. The findings from this review can be broadly categorised into three levels: (I) findings with relatively solid support, (II) emerging hypotheses, and (III) gaps in the literature. These are discussed in the next section.

Figure 3.

Epigenetics and its impact on clinical variability in Fabry disease. Abbreviations: alpha-galactosidase A (GLA); bidirectional promoter (BDP); collagen type IV alpha gene (COL4A); zinc finger protein gene (ZFP57). Figure created using images from BioRender (https://biorender.com/).

4.1. Genetic Modifiers

When viewed broadly across the epigenetic landscape of Fabry disease severity, genetic modifiers could play a role as disease biomarkers.

4.1.1. Findings with Relatively Solid Support

Evidence shows that specific biomarkers and clinical tools can be used to assist in the diagnosis and stratification of Fabry disease in males. For example, the Fabry Outcome Survey (FOS) [34] and Fabry Registry [79] disease registries could help risk-stratify individuals with Fabry disease and improve prognosis. Levels of α-GAL A are essential in determining the pathogenicity of a variant in males, and levels of plasma lyso-Gb3 are a helpful diagnostic biomarker in males [35]. Interestingly, our analysis also revealed a potentially higher inflammatory burden in individuals with Fabry disease [64]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines have been implicated in the pathophysiology of Fabry disease, reinforcing the role of inflammation in this condition [80,81,82]. Evidence has shown that peripheral blood mononuclear cells in individuals with Fabry disease have increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [83]. In Fabry disease, glycolipid deposits in lysozymes trigger chronic inflammation, leading to progressive organ damage [82].

4.1.2. Emerging Hypothesis

The review showed a promising yet preliminary hypothesis for understanding how genetic modifiers influence Fabry disease. While plasma lyso-Gb3 is helpful in diagnosing hemizygous males, its ability to detect disease burden in heterozygous females and those with non-classical GLA variants [35] is questionable. Normal levels of plasma lyso-Gb3 could be considered in later-onset forms [17]; however, plasma lyso-Gb3 might not be able to accurately distinguish between early- and later-onset forms of Fabry disease in a newborn screening study [84]. In non-classic and female individuals, lyso-Gb3 should be viewed together with other diagnostic and monitoring tools [85].

Methylation at site 78,504 CpG in the promoter region of the calcitonin receptor gene could potentially serve as an epigenetic biomarker for individuals with more severe Fabry disease [56]. However, the small sample size in this study precludes the drawing of meaningful inferences. Methylated lyso-Gb3 isoforms could help identify individuals with later-onset variants [86]. However, greater emphasis needs to be placed on longitudinal, multicentre studies before DNA methylation of the promoter region of the calcitonin receptor gene and/or methylated lyso-Gb3 isoforms can be considered clinically relevant.

While there are biomarkers for Fabry disease [87], the biochemical biomarkers for detecting Fabry disease in heterozygous females are limited [84,85]. In this context, genetic modifiers may be more relevant in heterozygous females, who present later than males, with variable disease severity [88]. Genetic modifiers could, therefore, have an increasingly important role in modifying the clinical presentation in females with the same GLA pathogenic variant. Preliminary evidence from a proteomics-based analysis has revealed a role for interleukin 7 (IL-7) in stratifying individuals, especially those with the non-classical form [80]. However, further studies in a larger cohort are needed to determine whether a proteomic signature can be clinically utilised as a diagnostic tool in Fabry disease. Profiling mitochondrial dysregulation through mitochondrial DNA haplogroups in 77 individuals with Fabry disease provides preliminary evidence for mitochondrial genetic variation in disease variability [60]. The study of mitomiRs further opens new avenues for profiling metabolic processes in Fabry disease [69] but may also help to identify metabolic mechanisms underpinning other lysosomal storage disorders [89].

4.1.3. Gaps in the Literature

The present review showed that studies on reliable biochemical biomarkers for detecting and monitoring disease progression in heterozygous females are still lacking [84,85]. Furthermore, the value of plasma lyso-GB3 in (I) diagnosing non-classical and female patients and (II) differentiating between disease severity or onset remains unclear. The literature also indicates that while epigenetic modifiers and inflammatory markers show promise, studies validating epigenetic and inflammatory markers, such as CpG methylation IL-7, for routine clinical testing are lacking. A targeted research approach is required to address these gaps, especially for heterozygous individuals.

4.2. Differential Methylation Profiles

The thematic analysis also revealed that specific genes exhibit differential methylated profiles in males with Fabry disease [52,62].

4.2.1. Findings with Relatively Solid Support

In Fabry disease, evidence from the FOS has shown that the incidence of cerebrovascular events ranges from 11.1 to 25% in males and from 15.7 to 21% in females [34,90,91], with these events more frequently occurring at a younger age in males [91]. The vasculopathy in Fabry disease is due to the deleterious impact of lyso-Gb3 on blood vessels and its interaction with the nitric oxide pathway [92,93]. A recent single-centre study has evaluated the cardiac phenotypes in 42 individuals with Fabry disease [94]. This study showed that even at early disease stages, cardiac abnormalities are present, and those with classical variants had a statistically elevated risk of experiencing an adverse cardiovascular event. The authors suggest that genotypes modulate functional cardiac remodelling in Fabry disease [94].

4.2.2. Emerging Hypothesis

In the current study, preliminary evidence suggests that decreased methylation of COL4A1 and COL4A2 may play a role in disrupting blood vessel architecture and contribute to vasculopathy in individuals with Fabry disease [52]. These genes are responsible for maintaining basement membranes and are involved in a range of multi-organ disorders, including cerebrovascular pathologies [95]. A broad spectrum of cerebrovascular manifestations has been identified in those with COL4A1 and COL4A2 pathogenic variants [96]. Genome-wide methylation profiling in five male individuals with Fabry disease also revealed differential methylation profiles [62]. This proof-of-concept study suggests that episignatures could be used as diagnostic markers. While these results are promising and suggest that specific genes are differentially methylated in Fabry disease, the findings should be interpreted with caution. One study was conducted using endothelial cell models derived from a male individual with Fabry disease and does not entirely capture the complexity of the disease [52]. Moreover, the small sample size in studies limits their ability to identify specific episignatures that can reliably discriminate between individuals with Fabry disease [62].

Emerging evidence also suggests that a dysregulated methionine cycle may also contribute to differential methylation profiles in individuals with Fabry disease [52], and this mirrors the findings in other X-linked disorders [25,97]. When viewed together, differential methylation of COL4A1 and COL4A2 genes suggests an association with cerebrovascular vulnerability in males with Fabry disease. This, coupled with a dysregulation in the methionine cycle, allows further insight into how methylation can affect disease manifestations in Fabry disease and draws parallels with other X-linked disorders.

4.2.3. Gaps in the Literature

Further research is needed to better understand the epigenetic landscape of Fabry disease. Most notably, evidence suggesting a causal relationship between altered methylation of COL4A1 and COL4A2 genes and cerebrovascular pathologies in Fabry disease remains to be firmly established. Unlike some other X-linked disorders, the role of a dysregulated methionine cycle in Fabry disease is still underexplored. The lack of data also extends to gender-specific epigenetic mechanisms, especially the literature on the epigenetic mechanisms in heterozygous females, where disease patterns are more variable. While differential methylation profiles in Fabry disease are a promising area of research, longitudinal studies are needed to assess whether modifying methylation profiles could help to improve clinical outcomes in Fabry disease.

4.3. X Chromosome Inactivation

4.3.1. Findings with Relatively Solid Support

In Fabry disease, evidence from studies on XCI in females with Fabry disease varied. There were inconsistent results regarding the influence of XCI on clinical manifestations [53,54,55,59]. The heterogeneous clinical picture in females often leads to misdiagnosis. Indeed, about 25% of individuals in the FOS were misdiagnosed [34]. Misdiagnosis can also lead to delays in initiating disease-modifying therapies, which is a crucial aspect because evidence has shown that timely intervention using ERT can lower the risk to organs, regardless of the disease type [98]. In heterozygous females with Fabry disease, XCI may play a role in clinical variability.

4.3.2. Emerging Hypothesis

Variability in XCI patterns is influenced by age-related changes in XCI and tissue-specific organ manifestations [66]. Methodological differences in the assessment of XCI could influence the outcome of studies [75]. Approaches such as ultra-deep DNA methylation analyses have been proposed as promising tools to facilitate diagnosis in females with Fabry disease [33,75], and this could theoretically optimise the time for treatment initiation with disease-modifying treatments, such as ERT and chaperone therapies [99], before irreversible organ damage occurs. Other factors implicated in clinical variability may be attributed to the number of genes that escape XCI [30,75], which lead to differences at the cellular level even within the same tissue [16]. This phenomenon adds another layer to phenotypic variability in Fabry disease. However, this hypothesis remains preliminary and would require further investigation before the clinical significance of genes escaping XCI can be established.

4.3.3. Gaps in the Literature

Despite insights into XCI, gaps remain in understanding the precise role of XCI in the clinical variability in Fabry disease. The purported mechanisms of (I) age-related changes, (II) tissue-specific mechanisms, and (III) XCI escape have not been fully elucidated. Inconsistencies across studies also underscore the need for research into standardised methods to assess XCI patterns accurately, and while ultra-deep methylation shows promise, this technique has not been validated in individuals with Fabry disease.

4.4. Limitations

The lead author (J.S.) performed the narrative review; however, the review was not undertaken blindly, as preliminary discussions with the third author (U.R.) addressed key issues and concepts. These included unmet needs, especially relating to genetic modifiers, in female individuals with Fabry disease. The SANRA scale was used as a self-assessment tool to evaluate the quality of the review. Higher scores indicate better quality, with a maximum of 12. This review was prepared in accordance with the SANRA framework, and the self-assessment score is presented in Supplementary Table S1. Another limitation is the interpretative nature of thematic analysis. Colour coding of words/terms that led to the emergence of themes was performed manually by the lead author. This process partly followed the method of conducting a thematic analysis used in a previous study by the first author, which examined autonomic dysregulation in another X-linked disorder, RTT [100]. However, in this study, the thematic analysis was performed by a single author (J.S.), increasing the risk of bias that could have unintentionally influenced the identification of themes. This limitation in the thematic analysis can affect the generalisability of the findings. However, to reduce the bias, the data extraction and thematic framework were reviewed by another author (U.R.), and any disagreements were resolved before data extraction, and the thematic framework was finalised. The following strategies were also employed to minimise interpretive bias: (I) adopting a structured framework for the thematic analysis as described [43], (II) using 6Rs to avoid the drift of keywords and terms, (III) employing the principles of 4Rs to assist in the identification of themes, (IV) using inductive coding and a data-driven approach to allow themes to emerge naturally, and (V) having the thematic framework reviewed by another author (U.R.) to ensure consistency of keywords and codes.

In summary, while the use of the SANRA assessment and structured framework for thematic analysis strengthened the methodological rigour of the review, the absence of independent data extraction can introduce bias. However, the third author (U.R.) reviewed the data extraction and thematic framework. Disagreements were resolved before finalising the thematic framework. Inter-coder statistics were not performed. However, as mentioned previously, this does not necessarily undermine the validity of the coding [101]. The limitations of the underlying literature were also clearly acknowledged, including small and heterogeneous cohorts, lack of replication, and variability in methods. Despite these constraints, the review collected and organised a fragmented and limited body of evidence on an emerging topic in Fabry disease.

4.5. Future Directions

Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms have been adopted to address medical issues in individuals with Fabry disease [102]. These range from supporting diagnosis using electronic health records to a better understanding of organ-specific disease progression [102]. Promoter-level transcriptome analysis alongside artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms was employed to identify the chimerin 1 (CHN1) gene as a potential biomarker for cardiac issues in 15 male individuals with Fabry disease [103]. However, this finding would need to be replicated in a larger sample to assess whether this biomarker could be used in clinical settings. In this view, future studies of epigenetics could utilise AI methodologies to enhance our understanding of Fabry disease.

5. Conclusions

The combined narrative review and thematic analysis revealed important insights into the epigenetic mechanisms of Fabry disease. This mapping exercise may help to inform health professionals and researchers working in Fabry disease. Robust longitudinal and multicentre studies would be essential before any proposed epigenetic biomarker can be considered clinically reliable and adopted into standard care. Ultimately, the goal of unravelling epigenetic mechanisms is to facilitate the diagnosis and management of Fabry disease, especially at early stages before symptoms become entrenched and irreversible organ damage occurs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cimb47100855/s1.

Author Contributions

U.R. and J.S. conceived and designed the study. J.S. performed the data extraction. J.S. and U.R. reviewed the data extraction and themes. J.S. wrote drafts. J.S. and U.R. prepared the final manuscript. J.S., P.S., and U.R. reviewed the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this narrative review was derived from articles openly available in the Embase, PsycINFO (https://www.ovid.com/), and PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) databases.

Conflicts of Interest

J.S. was previously a Trial Research Methodologist on the Sarizotan Clinical Trial (Protocol Number Sarizotan/001/II/2015; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02790034) and previously was a Research Manager for the Anavex Life Sciences Corp. clinical trial (Protocol Number ANAVEX2-73-RS-002). J.S. also advises for Reverse Rett. P.S. was a Principal Investigator (PI) on the following trials: Sarizotan (Protocol Number Sarizotan/001/II/2015), GW Pharma (Protocol Number GWND18064), and Anavex Life Sciences Corp. (Protocol Numbers ANAVEX2-73-RS-002 and ANAVEX2-73-RS-003). He has also been on the advisory board and received funding from Acadia Pharmaceuticals. P.S. is also the co-inventor of the HealthTrackerTM platform, where he is a shareholder and its Chief Executive Officer. U.R. has no conflicts related to this manuscript. Outside of the manuscript, U.R. has received honoraria for lectures/advisory boards from Amicus, Chiesi, Sanofi, and Takeda and institutional research grants from Amicus, Chiesi, Denali, IntraBio, and Takeda.

References

- Migeon, B.R. Why females are mosaics, X-chromosome inactivation, and sex differences in disease. Gend. Med. 2007, 4, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Theunissen, T.W. Modeling X-chromosome inactivation and reactivation during human development. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2023, 82, 102096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, M.F. Gene action in the X-chromosome of the mouse (Mus musculus L.). Nature 1961, 190, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Luo, J.; Yu, H.; Rattner, A.; Mo, A.; Wang, Y.; Smallwood, P.M.; Erlanger, B.; Wheelan, S.J.; Nathans, J. Cellular resolution maps of X chromosome inactivation: Implications for neural development, function, and disease. Neuron 2014, 81, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert Finestra, T.; Gribnau, J. X chromosome inactivation: Silencing, topology and reactivation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017, 46, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobyns, W.B.; Filauro, A.; Tomson, B.N.; Chan, A.S.; Ho, A.W.; Ting, N.T.; Oosterwijk, J.C.; Ober, C. Inheritance of most X-linked traits is not dominant or recessive, just X-linked. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2004, 129, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puck, J.M.; Nussbaum, R.L.; Conley, M.E. Carrier detection in X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency based on patterns of X chromosome inactivation. J. Clin. Investig. 1987, 79, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolduc, V.; Chagnon, P.; Provost, S.; Dubé, M.P.; Belisle, C.; Gingras, M.; Mollica, L.; Busque, L. No evidence that skewing of X chromosome inactivation patterns is transmitted to offspring in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos-Landgraf, J.M.; Cottle, A.; Plenge, R.M.; Friez, M.; Schwartz, C.E.; Longshore, J.; Willard, H.F. X chromosome-inactivation patterns of 1005 phenotypically unaffected females. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 79, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posynick, B.J.; Brown, C.J. Escape From X-Chromosome Inactivation: An Evolutionary Perspective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy, A.K.; Benke, T.A.; Marsh, E.D.; Neul, J.L. Rett syndrome: The natural history study journey. Ann. Child Neurol. Soc. 2024, 2, 189–205, Erratum in Ann. Child Neurol. Soc. 2025, 3, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Butler, K.M.; Abidi, F.; Gass, J.; Beisang, A.; Feyma, T.; Ryther, R.C.; Standridge, S.; Heydemann, P.; Jones, M.; et al. Analysis of X-inactivation status in a Rett syndrome natural history study cohort. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2022, 10, e1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiol, C.; Vidal, S.; Pascual-Alonso, A.; Blasco, L.; Brandi, N.; Pacheco, P.; Gerotina, E.; O’callaghan, M.; Pineda, M.; Armstrong, J. Rett Working Group. X chromosome inactivation does not necessarily determine the severity of the phenotype in Rett syndrome patients. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, H.; Evans, J.; Leonard, H.; Colvin, L.; Ravine, D.; Christodoulou, J.; Williamson, S.; Charman, T.; Bailey, M.E.S.; Sampson, J.; et al. Correlation between clinical severity in patients with Rett syndrome with a p.R168X or p.T158M MECP2 mutation, and the direction and degree of skewing of X-chromosome inactivation. J. Med. Genet. 2007, 44, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, J.K.; Fang, X.; Caylor, R.C.; Skinner, S.A.; Friez, M.J.; Percy, A.K.; Neul, J.L. Normalized Clinical Severity Scores Reveal a Correlation between X Chromosome Inactivation and Disease Severity in Rett Syndrome. Genes 2024, 15, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Risi, T.; Vinciguerra, R.; Cuomo, M.; Della Monica, R.; Riccio, E.; Cocozza, S.; Imbriaco, M.; Duro, G.; Pisani, A.; Chiariotti, L. DNA methylation impact on Fabry disease. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, D.P.; Levade, T.; Hachulla, E.; Knebelmann, B.; Lacombe, D. Challenging the traditional approach for interpreting genetic variants: Lessons from Fabry disease. Clin. Genet. 2022, 101, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, D.P. Fabry disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciapuoti, M.; Bertoldi, G.; Caputo, I.; Driussi, G.; Carraro, G.; Calò, L.A. Oxidative stress and its role in Fabry disease. J. Nephrol. 2024, 37, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoncini, C.; Torri, S.; Montano, V.; Chico, L.; Gruosso, F.; Tuttolomondo, A.; Pinto, A.; Simonetta, I.; Cianci, V.; Salviati, A.; et al. Oxidative stress biomarkers in Fabry disease: Is there a room for them? J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 3741–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortelazzo, A.; De Felice, C.; Guerranti, R.; Signorini, C.; Leoncini, S.; Pecorelli, A.; Zollo, G.; Landi, C.; Valacchi, G.; Ciccoli, L.; et al. Subclinical inflammatory status in Rett syndrome. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 480980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, W.A.; Percy, A.K.; Neul, J.L.; Cobb, S.R.; Pozzo-Miller, L.; Issar, J.K.; Ben-Zeev, B.; Vignoli, A.; Kaufmann, W.E. Rett syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, A.T.; Jensen, T.S. Neurological manifestations in Fabry’s disease. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2007, 3, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neul, J.L.; Kaufmann, W.E.; Glaze, D.G.; Christodoulou, J.; Clarke, A.J.; Bahi-Buisson, N.; Leonard, H.; Bailey, M.E.S.; Schanen, N.C.; Zappella, M.; et al. RettSearch Consortium. Rett syndrome: Revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 68, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Wilkins, G.; Goodman-Vincent, E.; Chishti, S.; Bonilla Guerrero, R.; McFadden, L.; Zahavi, Z.; Santosh, P. Co-Occurring Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase (MTHFR) rs1801133 and rs1801131 Genotypes as Associative Genetic Modifiers of Clinical Severity in Rett Syndrome. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artuso, R.; Papa, F.T.; Grillo, E.; Mucciolo, M.; Yasui, D.H.; Dunaway, K.W.; Disciglio, V.; A Mencarelli, M.; Pollazzon, M.; Zappella, M.; et al. Investigation of modifier genes within copy number variations in Rett syndrome. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 56, 508–515, Erratum in J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 57, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Whitfield, T.W.; Bell, G.W.; Guo, R.; Flamier, A.; Young, R.A.; Jaenisch, R. Exploring the complexity of MECP2 function in Rett syndrome. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2025, 26, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, R.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Huang, H.; Weng, J.; Tan, H.; Guo, T.; Wang, M.; Xie, J. The epigenetic modification of DNA methylation in neurological diseases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1401962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuu, Y.M.; Roberts, C.T.; Rastegar, M. MeCP2 Is an Epigenetic Factor That Links DNA Methylation with Brain Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Robinson, W.P. The causes and consequences of random and non-random X chromosome inactivation in humans. Clin. Genet. 2000, 58, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, A.J.; Stathaki, E.; Migliavacca, E.; Brahmachary, M.; Montgomery, S.B.; Dupre, Y.; Antonarakis, S.E. DNA methylation profiles of human active and inactive X chromosomes. Genome Res. 2011, 21, 1592–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, B.; Gonçalves, A.; Sousa, V.; Maia, N.; Marques, I.; Vale-Fernandes, E.; Santos, R.; Nogueira, A.J.A.; Jorge, P. Use of the FMR1 Gene Methylation Status to Assess the X-Chromosome Inactivation Pattern: A Stepwise Analysis. Genes 2022, 13, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Riso, G.; Cuomo, M.; Di Risi, T.; Della Monica, R.; Buonaiuto, M.; Costabile, D.; Pisani, A.; Cocozza, S.; Chiariotti, L. Ultra-Deep DNA Methylation Analysis of X-Linked Genes: GLA and AR as Model Genes. Genes 2020, 11, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, M.; Ramaswami, U.; Hernberg-Ståhl, E.; Hughes, D.A.; Kampmann, C.; Mehta, A.B.; Nicholls, K.; Niu, D.-M.; Pintos-Morell, G.; Reisin, R.; et al. Twenty years of the Fabry Outcome Survey (FOS): Insights, achievements, and lessons learned from a global patient registry. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenders, M.; Hennermann, J.B.; Kurschat, C.; Rolfs, A.; Canaan-Kühl, S.; Sommer, C.; Üçeyler, N.; Kampmann, C.; Karabul, N.; Giese, A.-K.; et al. Multicenter Female Fabry Study (MFFS)—Clinical survey on current treatment of females with Fabry disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2016, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palakuzhiyil, S.V.; Christopher, R.; Chandra, S.R. Deciphering the modifiers for phenotypic variability of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. World J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 11, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Deng, X.; Disteche, C.M. X-factors in human disease: Impact of gene content and dosage regulation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 30, R285–R295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kable, A.K.; Pich, J.; Maslin-Prothero, S.E. A structured approach to documenting a search strategy for publication: A 12 step guideline for authors. Nurse Educ. Today 2012, 32, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voniati, L.; Papadopoulos, A.; Ziavra, N.; Tafiadis, D. Communication Abilities, Assessment Procedures, and Intervention Approaches in Rett Syndrome: A Narrative Review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Santosh, P. Molecular Insights into Neurological Regression with a Focus on Rett Syndrome-A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, Z. The Essential Guide to Doing Your Research Project, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Yanagisawa, H.; Miyajima, T.; Wu, C.; Takamura, A.; Akiyama, K.; Itagaki, R.; Eto, K.; Iwamoto, T.; Yokoi, T.; et al. The severe clinical phenotype for a heterozygous Fabry female patient correlates to the methylation of non-mutated allele associated with chromosome 10q26 deletion syndrome. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 120, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.H.; Choi, J.M.; Ki, C.S.; Ma, S.K.; Yoo, H.W.; Kim, S.W. A late-onset male Fabry disease patient with somatic mosaicism of a classical GLA mutation: A case report. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 4926–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čerkauskaitė, A.; Čerkauskienė, R.; Miglinas, M.; Laurinavičius, A.; Ding, C.; Rolfs, A.; Vencevičienė, L.; Barysienė, J.; Kazėnaitė, E.; Sadauskienė, E. Genotype-Phenotype Correlation in a New Fabry-Disease-Causing Mutation. Medicina 2019, 55, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaide, M.A.; Al-Obaidi, I.I.; Vasylyeva, T.L. The potential consequences of bidirectional promoter methylation on GLA and HNRNPH2 expression in Fabry disease phenotypes in a family of patients carrying a GLA deletion variant. Biomed. Rep. 2022, 17, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, O.; Ceylaner, S. Genetic Management Algorithm in High-Risk Fabry Disease Cases; Especially in Female Indexes with Mutations. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2021, 21, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, H.; Hossain, M.A.; Miyajima, T.; Nagao, K.; Miyashita, T.; Eto, Y. Dysregulated DNA methylation of GLA gene was associated with dysfunction of autophagy. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 126, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.S.; Balaji, U.; Shigeyasu, K.; Okugawa, Y.; Jabbarzadeh-Tabrizi, S.; Day, T.S.; Arning, E.; Marshall, J.; Cheng, S.H.; Gu, J.; et al. Dysregulated DNA methylation in the pathogenesis of Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2022, 33, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iza, S.N.; Lagos, S.O.; Yunis, J.J. DNA Methylation Analysis and Phenotype Severity in Fabry Disease. J. Inborn Errors Metab. Screen. 2025, 13, e20230007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossanti, R.; Nozu, K.; Fukunaga, A.; Nagano, C.; Horinouchi, T.; Yamamura, T.; Sakakibara, N.; Minamikawa, S.; Ishiko, S.; Aoto, Y.; et al. X-chromosome inactivation patterns in females with Fabry disease examined by both ultra-deep RNA sequencing and methylation-dependent assay. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2021, 25, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juchniewicz, P.; Kloska, A.; Tylki-Szymańska, A.; Jakóbkiewicz-Banecka, J.; Węgrzyn, G.; Moskot, M.; Gabig-Cimińska, M.; Piotrowska, E. Female Fabry disease patients and X-chromosome inactivation. Gene 2018, 641, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, A.; Metz, T.; Schanzer, A.; Greber-Platzer, S.; Item, C.B. Aberrant DNA methylation of calcitonin receptor in Fabry patients treated with enzyme replacement therapy. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignani, R.; Pieruzzi, F.; Berri, F.; Burlina, A.; Chinea, B.; Gallieni, M.; Pieroni, M.; Salviati, A.; Spada, M. FAbry STabilization indEX (FASTEX): An innovative tool for the assessment of clinical stabilization in Fabry disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2016, 9, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Wu, C.; Yanagisawa, H.; Miyajima, T.; Akiyama, K.; Eto, Y. Future clinical and biochemical predictions of Fabry disease in females by methylation studies of the GLA gene. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2019, 20, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echevarria, L.; Benistan, K.; Toussaint, A.; Dubourg, O.; Hagege, A.A.; Eladari, D.; Jabbour, F.; Beldjord, C.; De Mazancourt, P.; Germain, D.P. X-chromosome inactivation in female patients with Fabry disease. Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoncini, C.; Chico, L.; Concolino, D.; Sestito, S.; Fancellu, L.; Boadu, W.; Sechi, G.; Feliciani, C.; Gnarra, M.; Zampetti, A.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups may influence Fabry disease phenotype. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 629, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ren, H.; Shen, P.; Wang, W.; Xu, Y.; Ni, L.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; et al. Genotype: A Crucial but Not Unique Factor Affecting the Clinical Phenotypes in Fabry Disease. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Risi, T.; Cuomo, M.; Vinciguerra, R.; Ferraro, S.; Della Monica, R.; Costabile, D.; Buonaiuto, M.; Trio, F.; Capoluongo, E.; Visconti, R.; et al. Methylome Profiling in Fabry Disease in Clinical Practice: A Proof of Concept. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levstek, T.; Breznik, N.; Vujkovac, B.; Nowak, A.; Trebušak Podkrajšek, K. Dynamics of Leukocyte Telomere Length in Patients with Fabry Disease. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Wasiak, S.; Tsujikawa, L.M.; Rakai, B.D.; Stotz, S.C.; Wong, N.C.W.; Johansson, J.O.; Sweeney, M.; Mohan, C.M.; Khan, A.; et al. Inhibition of epigenetic reader proteins by apabetalone counters inflammation in activated innate immune cells from Fabry disease patients receiving enzyme replacement therapy. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2022, 10, e00949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagenhäuser, L.; Rickert, V.; Sommer, C.; Wanner, C.; Nordbeck, P.; Rost, S.; Üçeyler, N. X-chromosomal inactivation patterns in women with Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2022, 10, e2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Řeboun, M.; Sikora, J.; Magner, M.; Wiederlechnerová, H.; Černá, A.; Poupětová, H.; Štorkánova, G.; Mušálková, D.; Dostálová, G.; Goláň, L.; et al. Pitfalls of X-chromosome inactivation testing in females with Fabry disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2022, 188, 1979–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokan Vujkovac, A.; Novaković, S.; Vujkovac, B.; Števanec, M.; Škerl, P.; Šabovič, M. Aging in Fabry Disease: Role of Telomere Length, Telomerase Activity, and Kidney Disease. Nephron 2020, 144, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignani, R.; Berti, G.M.; Vischini, G.; Di Costanzo, R.; Ciurli, F.; Fabbrizio, B.; Pasquinelli, G.; La Manna, G.; Capelli, I. The Fabry Nephropathy in Patients with N215S Variant. Nephron 2025, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Orsborne, C.; Eden, J.; Wallace, A.; Church, H.J.; Tylee, K.; Deepak, S.; Cassidy, C.; Woolfson, P.; Miller, C.; et al. Mosaic Fabry Disease in a Male Presenting as Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Cardiogenetics 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, J.; Fiordelisi, A.; Sorriento, D.; Cerasuolo, F.; Buonaiuto, A.; Avvisato, R.; Pisani, A.; Varzideh, F.; Riccio, E.; Santulli, G.; et al. Mitochondrial microRNAs Are Dysregulated in Patients with Fabry Disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2023, 384, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, R.; Santoro, C.; Mandoli, G.E.; Cuomo, V.; Sorrentino, R.; La Mura, L.; Pastore, M.C.; Bandera, F.; D’ascenzi, F.; Malagoli, A.; et al. Cardiac Imaging in Anderson-Fabry Disease: Past, Present and Future. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Ochoa, E.; Barwick, K.; Cif, L.; Rodger, F.; Docquier, F.; Pérez-Dueñas, B.; Clark, G.; Martin, E.; Banka, S.; et al. Comparison of methylation episignatures in KMT2B- and KMT2D-related human disorders. Epigenomics 2022, 14, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husson, T.; Lecoquierre, F.; Nicolas, G.; Richard, A.C.; Afenjar, A.; Audebert-Bellanger, S.; Badens, C.; Bilan, F.; Bizaoui, V.; Boland, A.; et al. Episignatures in practice: Independent evaluation of published episignatures for the molecular diagnostics of ten neurodevelopmental disorders. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 32, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, E.; Linhart, A.; Deegan, P.; Jurcut, R.; Pisani, A.; Torra, R.; Feldt-Rasmussen, U. Clinical management of female patients with Fabry disease based on expert consensus. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, A.; Schaller, K.; Belche, V.; Cybulla, M.; Grünert, S.C.; Moers, N.; Sass, J.O.; Kaech, A.; Hannibal, L.; Spiekerkoetter, U. Defective lysosomal storage in Fabry disease modifies mitochondrial structure, metabolism and turnover in renal epithelial cells. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2021, 44, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Sidransky, E.; Tayebi, N. The role of epigenetics in lysosomal storage disorders: Uncharted territory. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 122, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadra, N.; Schultz-Rogers, L.E.; Chanana, P.; Cousin, M.A.; Macke, E.L.; Ferrer, A.; Pinto E Vairo, F.; Olson, R.J.; Oliver, G.R.; Mulvihill, L.A.; et al. Identification of skewed X chromosome inactivation using exome and transcriptome sequencing in patients with suspected rare genetic disease. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, C.; Ortiz, A.; Wilcox, W.R.; Hopkin, R.J.; Johnson, J.; Ponce, E.; Ebels, J.T.; Batista, J.L.; Maski, M.; Politei, J.M.; et al. Global reach of over 20 years of experience in the patient-centered Fabry Registry: Advancement of Fabry disease expertise and dissemination of real-world evidence to the Fabry community. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 139, 107603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebani, A.; Mauhin, W.; Abily-Donval, L.; Lesueur, C.; Berger, M.G.; Nadjar, Y.; Berger, J.; Benveniste, O.; Lamari, F.; Laforêt, P.; et al. A Proteomics-Based Analysis Reveals Predictive Biological Patterns in Fabry Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebani, A.; Barbey, F.; Dormond, O.; Ducatez, F.; Marret, S.; Nowak, A.; Bekri, S. Deep next-generation proteomics and network analysis reveal systemic and tissue-specific patterns in Fabry disease. Transl. Res. 2023, 258, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenfeld, P.; Feriozzi, S. Contribution of inflammatory pathways to Fabry disease pathogenesis. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 122, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francesco, P.N.; Mucci, J.M.; Ceci, R.; Fossati, C.A.; Rozenfeld, P.A. Fabry disease peripheral blood immune cells release inflammatory cytokines: Role of globotriaosylceramide. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2013, 109, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gragnaniello, V.; Burlina, A.P.; Commone, A.; Gueraldi, D.; Puma, A. Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease: Current Status of Knowledge. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2023, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaswami, U.; West, M.L.; Tylee, K.; Castillon, G.; Braun, A.; Ren, M.; Doobaree, I.U.; Howitt, H.; Nowak, A. The use and performance of lyso-Gb3 for the diagnosis and monitoring of Fabry disease: A systematic literature review. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2025, 145, 109110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaoui, M.; Boutin, M.; Lavoie, P.; Auray-Blais, C. Tandem mass spectrometry multiplex analysis of methylated and non-methylated urinary Gb3 isoforms in Fabry disease patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 2016, 452, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burlina, A.; Brand, E.; Hughes, D.; Kantola, I.; Krämer, J.; Nowak, A.; Tøndel, C.; Wanner, C.; Spada, M. An expert consensus on the recommendations for the use of biomarkers in Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 139, 107585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkin, R.J.; Laney, D.; Kazemi, S.; Walter, A. Fabry disease in females: Organ involvement and clinical outcomes compared with the general population. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepien, K.M.; Roncaroli, F.; Turton, N.; Hendriksz, C.J.; Roberts, M.; Heaton, R.A.; Hargreaves, I. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Lysosomal Storage Disorders: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Ginsberg, L.; FOS Investigators. Natural history of the cerebrovascular complications of Fabry disease. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 2005, 94, 24–27; discussion 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Clarke, J.T.; Giugliani, R.; Elliott, P.; Linhart, A.; Beck, M.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; FOS Investigators. Natural course of Fabry disease: Changing pattern of causes of death in FOS—Fabry Outcome Survey. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 46, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Martínez, D.; León-Cejas, L.; Reisin, R. Cerebrovascular disorders and Fabry disease. Rare Dis. Orphan Drugs J. 2024, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, S.M.; Twickler, T.B.; Aerts, J.M.; Linthorst, G.E.; Wijburg, F.A.; Hollak, C.E. Vasculopathy in patients with Fabry disease: Current controversies and research directions. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010, 99, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro, D.C.; Di Salvo, S.; Rodolico, M.S.; Losi, V.; Capodanno, D.; Monte, I.P. Cardiac Phenotypes in Fabry Disease: Genetic Variability and Clinical Severity Staging Correlation in a Reference Center Cohort. Genes 2025, 16, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, D.S.; Labelle-Dumais, C.; Gould, D.B. COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations and disease: Insights into pathogenic mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, R97–R110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guey S and Hervé, D. Main features of COL4A1-COL4A2 related cerebral microangiopathies. Cereb. Circ. Cogn. Behav. 2022, 3, 100140. [Google Scholar]

- Linnebank, M.; Kemp, S.; Wanders, R.J.; Kleijer, W.J.; van der Sterre, M.L.; Gartner, J.; Fliessbach, K.; Semmler, A.; Sokolowski, P.; Kohler, W.; et al. Methionine metabolism and phenotypic variability in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Neurology 2006, 66, 442–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.; Linhart, A.; Gurevich, A.; Kalampoki, V.; Jazukeviciene, D.; Feriozzi, S.; FOS Study Group. Prompt Agalsidase Alfa Therapy Initiation is Associated with Improved Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in a Fabry Outcome Survey Analysis. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2021, 15, 3561–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidemann, F.; Jovanovic, A.; Herrmann, K.; Vardarli, I. Chaperone Therapy in Fabry Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Lanzarini, E.; Santosh, P. Autonomic dysfunction and sudden death in patients with Rett syndrome: A systematic review. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020, 45, 150–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Manginas, A.; Wilkins, G.; Santosh, P. A Comprehensive Analysis Examining the Role of Genetic Influences on Psychotropic Medication Response in Children. Genes 2025, 16, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, D.P.; Gruson, D.; Malcles, M.; Garcelon, N. Applying artificial intelligence to rare diseases: A literature review highlighting lessons from Fabry disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Nakata, N.; Izuka, S.; Hongo, K.; Nishikawa, M. Using artificial intelligence and promoter-level transcriptome analysis to identify a biomarker as a possible prognostic predictor of cardiac complications in male patients with Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2024, 41, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]