Abstract

Coronaviruses represent a significant class of viruses that affect both animals and humans. Their replication cycle is strongly associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which, upon virus invasion, triggers ER stress responses. The activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) within infected cells is performed from three transmembrane receptors, IRE1, PERK, and ATF6, and results in a reduction in protein production, a boost in the ER’s ability to fold proteins properly, and the initiation of ER-associated degradation (ERAD) to remove misfolded or unfolded proteins. However, in cases of prolonged and severe ER stress, the UPR can also instigate apoptotic cell death and inflammation. Herein, we discuss the ER-triggered host responses after coronavirus infection, as well as the pharmaceutical targeting of the UPR as a potential antiviral strategy.

Keywords:

unfolded protein response; IRE1; ATF6; PERK; ER stress; coronavirus; CoV; pharmacological inhibition 1. Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a membrane organelle that expands throughout the cytoplasm of the eukaryotic cell. The ER plays a crucial role in essential cellular functions, including protein folding, lipid and sterol synthesis, the metabolism of carbohydrates, and calcium storage [1]. Various factors such as hypoxia, glucose deprivation, acidosis, altered calcium levels, metabolic imbalances, infections, and inflammation can disrupt the ER function, mainly protein folding [2,3]. This disruption leads to changes in the ER’s capacity to mitigate the need for proper protein folding and results in the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins, a condition called ER stress. ER stress triggers the activation of the adaptive or survival unfolded protein response (UPR) system to counteract this stress [4]. However, the excessive activation of the UPR mechanism (proapoptotic UPR) can lead to adverse effects for the cell, such as apoptosis [3,5].

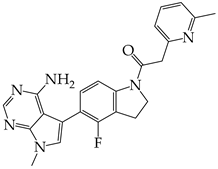

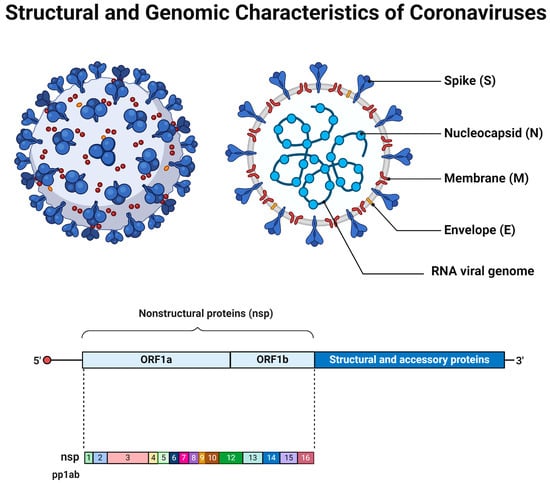

Coronaviruses are enveloped viruses of a spherical or pleiotropic shape, with a diameter between 80 and 150 nm [6]. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses has classified coronaviruses into the Order of Nidovirales, Family of Coronaviridae, and Subfamily of Orthocoronavirinae. They can be further divided into four genera: alpha (α-), beta (β-), gamma (γ-), and delta (δ-) coronaviruses [7,8]. While alpha- and betacoronaviruses primarily infect mammals, gamma- and deltacoronaviruses infect a wider range of animals, with aves being the most common host. It seems that these viruses can infect a variety of species, including humans. Notably, seven—two alpha and five beta—coronaviruses, known as the HCoV class, can infect humans and cause mild to moderate respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms [9,10]. The additional three members (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS-CoV) have been associated with severe respiratory distress conditions, causing epidemic and/or pandemic healthcare crises [11,12,13]. In accordance with human coronaviruses, animal-infecting CoVs can cause either respiratory or enteric symptoms [14,15]. Coronaviruses possess a single-stranded positive-sense RNA molecule [(+)ssRNA] varying in size from 26 to 32 kb [16,17]. Their genomic RNA can be directly translated by infected cells to produce the structural viral proteins, spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins, that contribute to the virions’ formation and shaping. Also, it encodes the non-structural proteins (NSPs) and/or accessory proteins that enhance the virus’s replication and thus virulence [18,19,20] (Figure 1). Their genomic features appear to be critical for understanding the viral infectivity and transmission dynamics, but the natural accumulation of mutations over time due to error-prone replication, the lack of proofreading mechanisms, adaptation to the host cellular environment, and cross-species transmission result in genetic diversity regarding the coronaviruses [21,22,23].

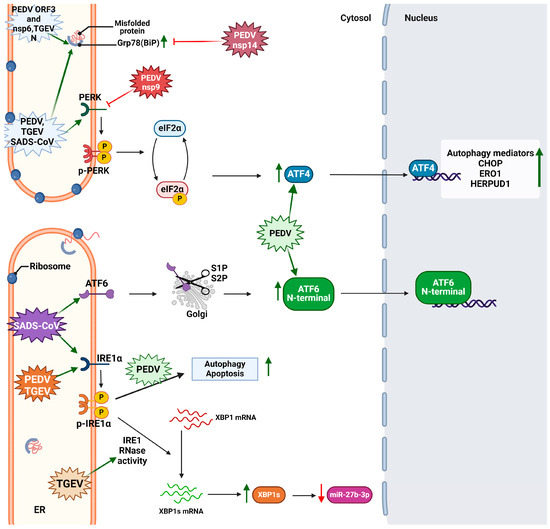

Figure 1.

The general structural and genomic characteristics of the members of coronavirus family. Adapted from “Human Coronavirus Structure” and “Genome organization of SARS-CoV” by BioRender.com. Retrieved from https://app.biorender.com/biorender-templates (accessed on 28 March 2024).

The translation of viral proteins is strongly associated with the ER, and, upon viral infection and replication, the host cells induce a UPR [24]. For example, SARS-CoV-2 alters the structure of the ER to create replication sites, leading to ER stress and UPR activation [25]. In addition, swine coronaviruses like porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) can induce ER rearrangement and provoke ER stress [26]. Herein, we summarize the latest data concerning the crosstalk between coronavirus infection and UPR signaling, as well as the potential of therapeutically targeting the UPR against coronavirus infections.

2. The Unfolded Protein Response

The role of the UPR is to counteract the ER stress, and it serves three main purposes: adaptive response, feedback control, and cell fate. In its adaptive role, the UPR seeks to alleviate endoplasmic reticulum ER stress and restore the ER equilibrium [27]. Upon the successful mitigation of stress, feedback mechanisms deactivate the UPR signaling pathways [28]. During the adaptive response, it retains proteostasis by reducing protein synthesis, increasing membrane lipid biosynthesis and ER membrane activity, and inducing the expression of ER-luminal chaperones and the components of the ER-associated degradation machinery (ERAD) [29]. Also, the ER export is regulated, and, currently, studies have proven that it is contingent upon the condition of the folding machinery and the internal environment within the stressed ER [30]. Nevertheless, the prolonged and excessive activation of the UPR may eventually induce cell death through apoptosis and autophagy [31].

The crucial role of the UPR is obvious not only in health but also in diseases. The malfunctioning of the UPR has been associated with diverse diseases including cancer [32], cardiovascular diseases [33], and neurogenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease [34]. Furthermore, the growing evidence regarding the role of the UPR in the immunological response supports its implication in infections and inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [35].

During viral infections, the UPR is used as machinery to defend the host cell. However, many viruses like Zika virus, coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV-2 [36], and herpesviruses [37] have managed to hijack this system and induce massive protein expression and viral replication [38]. Positive-stranded RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 also recruit the UPR to induce ER membrane rearrangements and to favor the synthesis of the viral membrane [36].

2.1. Activation of the UPR Sensors and Signal Transduction

The UPR signals through three different transmembrane receptors, inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), protein kinase R (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6). These receptors consist of three domains, the luminal, the transmembrane, and the cytosolic domain. They act as sensors by detecting the unfolded protein levels through their luminal domains and convey this information to cytosolic effector pathways through their respective cytoplasmic domains, resulting in the downregulation of protein translation and increased removal of misfolded or unfolded proteins [39,40].

2.1.1. The IRE1 Signaling

IRE1 and PERK exhibit common activation ways. The receptors can directly be activated upon interaction with the misfolded proteins or upon dissociation from immunoglobulin-binding protein (BiP), otherwise known as glucose-regulated protein 78 (Grp78) [41]. IRE1’s structure is highly conserved through species, and two isoforms exist: IRE1a and IRE1b [42]. IRE1β functions as a dominant-negative inhibitor of IRE1a in different cell types like epithelial cells, while IREa is the main signal transducer [43].

The direct activation model proposes that unfolded proteins bind to a hydrophobic groove located in the N-terminal domain and permits the oligomerization and autophosphorylation of the IRE1 receptors [44]. However, the main activation pathway is through BiP, a chaperonin that holds a dual and crucial role in the ER function. In normal conditions, BiP is bound via the ERdj4/DNAJB9 into the luminal domain of IRE1 and supresses the activation of the UPR. Upon the accumulation of misfolded or unfolded proteins, the latter bind to BiP, disassociating from the receptor and enabling trans-autophosphorylation and oligomerization [40].

After the oligomerization of more than four monomers, the active C-terminal domain displays dual activity as it encompasses a kinase domain and an endoribonuclease domain. The kinase domain binds ATP and transphosphorylates the other monomers so as to activate the RNAase domain. This splices an intron of the x-box binding protein 1 XBP1 mRNA non-canonically, which then acts as a transcriptional factor and promotes the viability, expansion, and differentiation of cells [45,46]. The main target genes of XBP1s are the ER chaperones (Dnajb9, Dnajb11, Pdia3, and Dnajc3), the ERAD components (Edem1, Herpud1, and Hrd1), the folding enzymes, and the ER translocon (Sec61a1). Also, cell-specific genes are expressed [47]. The IRE-Xbp1 pathway is significant in various diseases, like metabolic conditions involving glucose and lipid metabolism, tumorigenesis, and cancer metastasis [48].

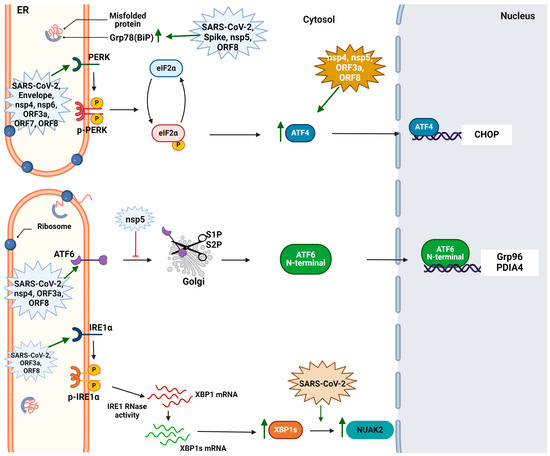

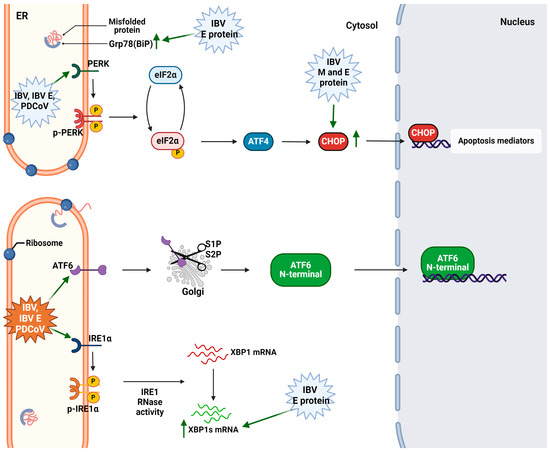

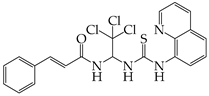

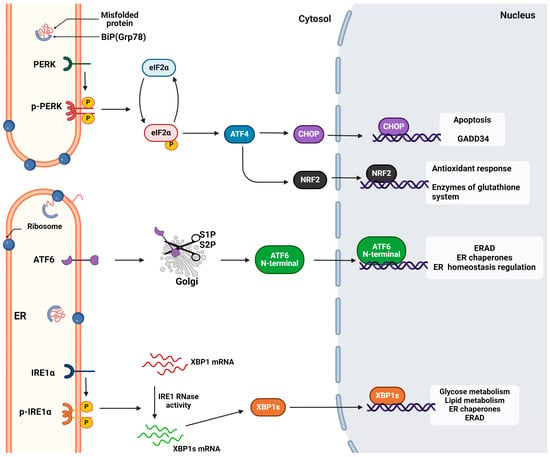

IRE1 also interacts with TRAF2 to initiate the inflammatory response and activate the protein kinases associated with cellular apoptosis, particularly apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1). This activation subsequently triggers the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) [2]. In severe stress conditions, the active RNAse activates the regulated IRE1-Dependent Decay RIDD branch. This cleaves mRNAs that encode mainly ER proteins and secondly cytosolic and nucleus-related proteins, leading to cell death [49] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The unfolded protein response mechanism. The activation and the signal transduction of the three (ATF6, IRE1, and PERK) sensors of UPR. Each respective pathway activates the transcription of a specific pool of genes to relieve ER stress and maintain ER and cell homeostasis. However, extended activation of UPR can lead to apoptosis or other pathological conditions. Retrieved from https://app.biorender.com/biorender-templates (accessed on 28 March 2024). Adapted from “Intracellular Layout—Endoplasmic Reticulum Signaling to Nucleus” by BioRender.com (accessed on 24 April 2024).

2.1.2. The PERK Signaling

The PERK branch is the most significant pathway for the host antiviral response. PERK shares a common activation pathway with IRE1 as its activation relies mainly upon the disassociation of BiP. In response to misfolded proteins, BiP is released and PERK multimerizes and is trans-autophosphorylated. The phosphorylated cytosolic domain acts as a kinase and phosphorylates the alpha subunit of the eukaryotic initiation factor eIF2 (eIF2a) specifically at Ser51. The phosphorylated eIF2a induces the expression of the bZip transcription factor 4 (ATF4), which regulates redox equilibrium, amino acid metabolism, and autophagy [50].

In the proapoptotic UPR, ATF4 interacts and subsequently activates CCAAT/enhancer binding homologous protein (CHOP) [51]. CHOP acts as a proapoptotic factor and upregulates the expression of growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible protein (GADD34), which plays a role in the dephosphorylation of elF2a, facilitating stress recovery. However, CHOP can also act as a pro-apoptotic factor by triggering caspase 8 via the death receptor 5 [5]. Also, the phosphorylated eIF2a suppresses the transcription of most mRNAs by inhibiting the exchange of GDP with GTP in the preinitiation translation complex. Noteworthily, eIF2a increases the transcription of ATF4 to promote cell death [3].

Except the regulation of cell survival and death, PERK has been linked with the direct activation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a transcription factor implicated in the oxidative response [52]. This factor regulates the expression of the genes responsible for the glutathione system and ROS elimination. Indirectly, as reported by Sarcinelli et al., PERK upregulates ATF4 and the latter upregulates the Nrf2 transcript [53] (Figure 2).

2.1.3. The ATF6 Signaling

ATF6 acts as a pro-survival branch, and its activation relies on the dissociation of BiP and exposure of the Golgi-targeting sequence. Thus, the receptor is translocated to the Golgi apparatus, and, after cleavage at sites 1 and 2, the active ATF6(N) fragment moves to the nucleus and binds to the ER stress response element (ERSE) I or II [54,55]. As a transcription factor, it upregulates the genes that encode ER chaperones Grp78 and Grp94, as well as ΧΒP1 [28]. Also, it has been reported that, except proteotoxic stress, ATF6 activation and translocation to the nucleus are mediated by the biosynthetic molecules, dihydrosphingosine and dihydroceramide, which bind directly to sequence motif VXXFIXXNY of the luminal domain [56].

The ATF6 branch is crucial for the retention of organelle homeostasis and ER capacity and in physiological development; it regulates osteogenesis, chondrogenesis, and neurogenesis. Its role has also been reported in diseases like cardiac hypertrophy [57] and ischemia [58]. The role of the ATF6 branch has also been investigated in viral infections and reported various responses [59] (Figure 2).

2.2. UPR Crosstalk with Other Pathways

The UPR is closely related to ERAD. This machinery comprises three stages: the recognition, reverse translocation, and degradation of misfolded proteins. During the selective recognition of substrates from chaperonins, the primary obstacle for the ERAD system is differentiating misfolded proteins from properly folded ones, a task made more difficult by the wide variety of secretory proteins [60]. After recognition, the proteins are reversely translocated through translocation channels, like Sec61, ERAD-L, and ERAD-M [61]. In this process, PERK and IRE1 crosstalk, and, specifically, PERK exerts an activation action on recognition, translocation, and degradation, while IRE1 impacts the translocation through the ER components and translocon upregulation [62].

ER stress has been extensively studied as a trigger of autophagy, a cellular process responsible for the degradation of malfunctioning organelles or protein aggregates. In this process, the three branches of the UPR cooperate and induce the formation of autophagosomes. However, the PERK--eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP cascade has a significant role in the expression of the ATG and LC3 genes [60,63]. Also, the IRE1a-XBP1 axis triggers the expression of Beclin-1, a protein that initiates autophagy [64]. A specific type of autophagy for the destruction of damaged mitochondria, mitophagy, has been reported to be initiated via the activation of ATF4 [65].

There is an interconnection between the signaling pathways of UPR, autophagy and oxidative stress response. Normally, the ER during protein synthesis produces excess amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and its redox state is closely controlled [52]. To maintain redox homeostasis, a closed loop is triggered. PERK forms a complex with endoplasmic reticulum oxidase 1 (ERO1a), a protein activated from the PERK--eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP axis. ERO1a is responsible for the oxidation of reduced PDI and consequently disulfide bond formation [66].

5. Conclusions

ER stress is a key component of the host response after a viral infection. The activation of the UPR is necessary to retain cellular homeostasis not only in the physiological conditions but also in diseases. The research conducted over the last decade has demonstrated that coronavirus replication leads to ER stress and initiates the UPR within infected cells. The potential of coronaviruses to infect both people and animals, along with the lack of an authorized treatment for severe cases, pose threats to public health, veterinary care, and the financial system. These factors, along with the rapid transmission, have rendered the development of new therapeutic approaches crucial. So far, there is little evidence regarding the potential use of UPR inhibitors in combating coronavirus infection, and most of the studies have focused on the in vitro testing of commercial inhibitors. Further preclinical testing and clinical trials will shed light on the potential use of UPR inhibitors as antiviral drugs. Due to the conserved nature of UPR signaling, it is important to investigate novel UPR inhibitors and their potential use as antiviral drugs. Also, limited data have been reported concerning the exact mechanism by which the virus activates the UPR and further triggers cellular responses such as redox homeostasis. Some questions that should be answered regard the possible antagonism of coronaviral proteins with BiPs upon binding to UPR transducers, the disruption of protein homeostasis, and the implications regarding pathological conditions like Ca2+ efflux and ROS accumulation. Further research regarding their interaction with the innate immune system is needed to clarify the virus pathogenesis. In this context, the investigation of the crosstalk between chronic UPR induction and long COVID symptoms could be addressed.

Author Contributions

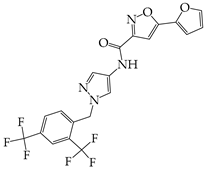

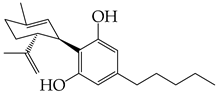

P.K. and M.P. contributed equally to writing the original draft. P.K., M.P. and E.P. provided the study material for the review. All authors (P.K., M.P., E.P. and T.C.-P.) participated in the editing and the revision of the manuscript. Figures and chemical structures were created by P.K. using Biorender.com (Accessed on 28 March 2024 and 24 April 2024) or ChemDraw software (ChemDraw® Ultra, Version 8.0). Supervision: T.C.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Perkins, H.T.; Allan, V. Intertwined and Finely Balanced: Endoplasmic Reticulum Morphology, Dynamics, Function, and Diseases. Cells 2021, 10, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, K.R.; Riaz, T.A.; Kim, H.-R.; Chae, H.-J. The Aftermath of the Interplay between the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response and Redox Signaling. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, A.; Schröder, M. The Unfolded Protein Response: An Overview. Biology 2021, 10, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Shi, C.; He, M.; Xiong, S.; Xia, X. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress: Molecular Mechanism and Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radanović, T.; Ernst, R. The Unfolded Protein Response as a Guardian of the Secretory Pathway. Cells 2021, 10, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.S.; Liu, D.X. Similarities and Dissimilarities of COVID-19 and Other Coronavirus Diseases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 75, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Tian, E.-K.; He, B.; Tian, L.; Han, R.; Wang, S.; Xiang, Q.; Zhang, S.; El Arnaout, T.; Cheng, W. Overview of Lethal Human Coronaviruses. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chathappady House, N.N.; Palissery, S.; Sebastian, H. Corona Viruses: A Review on SARS, MERS and COVID-19. Microbiol. Insights 2021, 14, 117863612110024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Liu, Z.; Chen, D. Human Coronaviruses: Origin, Host and Receptor. J. Clin. Virol. 2022, 155, 105246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.-G.; Xie, Q.-X.; Lao, H.-L.; Lv, Z.-Y. Human Coronaviruses and Therapeutic Drug Discovery. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, W.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, S.; Han, J.; Wu, Q. A Comparative Overview of COVID-19, MERS and SARS: Review Article. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chams, N.; Chams, S.; Badran, R.; Shams, A.; Araji, A.; Raad, M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Stroberg, E.; Duval, E.J.; Barton, L.M.; et al. COVID-19: A Multidisciplinary Review. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollarasouli, F.; Zare-Shehneh, N.; Ghaedi, M. A Review on Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Current Progress, Clinical Features and Bioanalytical Diagnostic Methods. Microchim. Acta 2022, 189, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, G.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhou, C.; Kong, W.; Su, J.; Li, G.; Si, H.; Ou, C. Which Strain of the Avian Coronavirus Vaccine Will Become the Prevalent One in China Next? Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1139089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Wang, Q.; Kenney, S.P.; Jung, K.; Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J. Porcine Deltacoronaviruses: Origin, Evolution, Cross-Species Transmission and Zoonotic Potential. Pathogens 2022, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassar, A.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Amin, F.G.; Magdy, M.; Elgharib, A.M.; Azzam, E.B.; Nasser, F.; Yousry, K.; Shamkh, I.M.; Mahdy, S.M.; et al. A Review of Human Coronaviruses’ Receptors: The Host-Cell Targets for the Crown Bearing Viruses. Molecules 2021, 26, 6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renu, K.; Prasanna, P.L.; Valsala Gopalakrishnan, A. Coronaviruses Pathogenesis, Comorbidities and Multi-Organ Damage—A Review. Life Sci. 2020, 255, 117839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabaan, A.A.; Alenazy, M.F.; Alshehri, A.A.; Alshahrani, M.A.; Al-Subaie, M.F.; Alrasheed, H.A.; Al Kaabi, N.A.; Thakur, N.; Bouafia, N.A.; Alissa, M.; et al. An Updated Review on Pathogenic Coronaviruses (CoVs) amid the Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Variants: A Look into the Repercussions and Possible Solutions. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 1870–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V’kovski, P.; Kratzel, A.; Steiner, S.; Stalder, H.; Thiel, V. Coronavirus Biology and Replication: Implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, Y.; Wang, K.; Qiu, S.; Lu, K.; Liu, Y. Comparing the Nucleocapsid Proteins of Human Coronaviruses: Structure, Immunoregulation, Vaccine, and Targeted Drug. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 761173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Ahmad Farouk, I.; Lal, S.K. COVID-19: A Review on the Novel Coronavirus Disease Evolution, Transmission, Detection, Control and Prevention. Viruses 2021, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Wan, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, F. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant: Recent Progress and Future Perspectives. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouresmaieli, M.; Ekrami, E.; Akbari, A.; Noorbakhsh, N.; Moghadam, N.B.; Mamoudifard, M. A Comprehensive Review on Efficient Approaches for Combating Coronaviruses. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadowaki, H.; Nishitoh, H. Signaling Pathways from the Endoplasmic Reticulum and Their Roles in Disease. Genes 2013, 4, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.; Cerikan, B.; Stahl, Y.; Kopp, K.; Magg, V.; Acosta-Rivero, N.; Kim, H.; Klein, K.; Funaya, C.; Haselmann, U.; et al. Enhanced SARS-CoV-2 Entry via UPR-Dependent AMPK-Related Kinase NUAK2. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 2559–2577.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-M.; Burrough, E. The Effects of Swine Coronaviruses on ER Stress, Autophagy, Apoptosis, and Alterations in Cell Morphology. Pathogens 2022, 11, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almanza, A.; Carlesso, A.; Chintha, C.; Creedican, S.; Doultsinos, D.; Leuzzi, B.; Luís, A.; McCarthy, N.; Montibeller, L.; More, S.; et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signalling—From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 241–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillary, R.F.; FitzGerald, U. A Lifetime of Stress: ATF6 in Development and Homeostasis. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 25, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, R. Emerging Role of the Unfolded Protein Response in ER Membrane Homeostasis. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 1-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, A. Effect of the Unfolded Protein Response on ER Protein Export: A Potential New Mechanism to Relieve ER Stress. Cell Stress Chaperones 2018, 23, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Lindholm, D.; Ren, J.; Pratico, D. ER Stress and UPR in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms, Pathogenesis, Treatments. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebeaupin, C.; Yong, J.; Kaufman, R.J. The Impact of the ER Unfolded Protein Response on Cancer Initiation and Progression: Therapeutic Implications. In HSF1 and Molecular Chaperones in Biology and Cancer; Mendillo, M.L., Pincus, D., Scherz-Shouval, R., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1243, pp. 113–131. ISBN 978-3-030-40203-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Bi, Y.; Sowers, J.R.; Hetz, C.; Zhang, Y. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Unfolded Protein Response in Cardiovascular Diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 499–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.S.; Tewari, D.; Sharma, G.; Kabir, M.T.; Barreto, G.E.; Bin-Jumah, M.N.; Perveen, A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Ashraf, G.M. Molecular Mechanisms of ER Stress and UPR in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 2902–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Song, N.-J.; Riesenberg, B.P.; Li, Z. The Emerging Roles of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Balancing Immunity and Tolerance in Health and Diseases: Mechanisms and Opportunities. Front. Immunol. 2020, 10, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prestes, E.B.; Bruno, J.C.P.; Travassos, L.H.; Carneiro, L.A.M. The Unfolded Protein Response and Autophagy on the Crossroads of Coronaviruses Infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 668034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, B.P.; McCormick, C. Herpesviruses and the Unfolded Protein Response. Viruses 2019, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirone, M. ER Stress, UPR Activation and the Inflammatory Response to Viral Infection. Viruses 2021, 13, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta-Alvear, D.; Karagöz, G.E.; Fröhlich, F.; Li, H.; Walther, T.C.; Walter, P. The Unfolded Protein Response and Endoplasmic Reticulum Protein Targeting Machineries Converge on the Stress Sensor IRE1. eLife 2018, 7, e43036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C.J.; Kopp, M.C.; Larburu, N.; Nowak, P.R.; Ali, M.M.U. Structure and Molecular Mechanism of ER Stress Signaling by the Unfolded Protein Response Signal Activator IRE1. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.M.; Abdelmalek, D.H.; Elfiky, A.A. GRP78: A Cell’s Response to Stress. Life Sci. 2019, 226, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, M.; Agrawal, N.; Chandra, R.; Dhawan, G. Targeting Unfolded Protein Response: A New Horizon for Disease Control. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2021, 23, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grey, M.J.; Cloots, E.; Simpson, M.S.; LeDuc, N.; Serebrenik, Y.V.; De Luca, H.; De Sutter, D.; Luong, P.; Thiagarajah, J.R.; Paton, A.W.; et al. IRE1β Negatively Regulates IRE1α Signaling in Response to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e201904048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siwecka, N.; Rozpędek-Kamińska, W.; Wawrzynkiewicz, A.; Pytel, D.; Diehl, J.A.; Majsterek, I. The Structure, Activation and Signaling of IRE1 and Its Role in Determining Cell Fate. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, F.; Doroudgar, S. IRE1/XBP1 and Endoplasmic Reticulum Signaling—From Basic to Translational Research for Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2022, 28, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, B.G.; Finnie, J.W. The Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Cell Survival and Death. J. Comp. Pathol. 2020, 181, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-M.; Kang, T.-I.; So, J.-S. Roles of XBP1s in Transcriptional Regulation of Target Genes. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, S. The Molecular Mechanism and Functional Diversity of UPR Signaling Sensor IRE1. Life Sci. 2021, 265, 118740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottens, F.; Efstathiou, S.; Hoppe, T. Cutting through the Stress: RNA Decay Pathways at the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Trends Cell Biol. 2023, S0962892423002362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetz, C.; Zhang, K.; Kaufman, R.J. Mechanism, Regulation and Functions of the Unfolded Protein Response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shacham, T.; Patel, C.; Lederkremer, G.Z. PERK Pathway and Neurodegenerative Disease: To Inhibit or to Activate? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, G.; Logue, S.E. Unfolding the Interactions between Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarcinelli, C.; Dragic, H.; Piecyk, M.; Barbet, V.; Duret, C.; Barthelaix, A.; Ferraro-Peyret, C.; Fauvre, J.; Renno, T.; Chaveroux, C.; et al. ATF4-Dependent NRF2 Transcriptional Regulation Promotes Antioxidant Protection during Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Cancers 2020, 12, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, O.B.V.; Pierre, A.S.; Pringle, M.A.; Tungkum, W.; Cao, Z.; Fleming, B.; Bulleid, N.J. Activation of the UPR Sensor ATF6α Is Regulated by Its Redox-Dependent Dimerization and ER Retention by ERp18. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2122657119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ziel, A.M.; Scheper, W. The UPR in Neurodegenerative Disease: Not Just an Inside Job. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, A.B.; Roberts, L.S.; Chandra, V.; Rivera, I.G.; Nomura, D.K.; Forbes, D.J.; Niwa, M. The UPR Activator ATF6 Responds to Proteotoxic and Lipotoxic Stress by Distinct Mechanisms. Dev. Cell 2018, 46, 327–343.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, C.; Aghajani, M.; Alcock, C.D.; Blackwood, E.A.; Sandmann, C.; Herzog, N.; Groß, J.; Plate, L.; Wiseman, R.L.; Kaufman, R.J.; et al. ATF6 Protects against Protein Misfolding during Cardiac Hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2024, 189, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glembotski, C.C.; Rosarda, J.D.; Wiseman, R.L. Proteostasis and Beyond: ATF6 in Ischemic Disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2019, 25, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yu, H.; Ding, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Fu, R. Molecular Mechanism of ATF6 in Unfolded Protein Response and Its Role in Disease. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T. Integrated Signaling System under Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Eukaryotic Microorganisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 4805–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Siggel, M.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Mi, W.; Svetlov, V.; Nudler, E.; Liao, M.; Hummer, G.; Rapoport, T.A. Structural Basis of ER-Associated Protein Degradation Mediated by the Hrd1 Ubiquitin Ligase Complex. Science 2020, 368, eaaz2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Qi, L. Quality Control in the Endoplasmic Reticulum: Crosstalk between ERAD and UPR Pathways. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2018, 43, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, K.I. Crosstalk between Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response and Autophagy in Human Diseases. Anim. Cells Syst. 2023, 27, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.-D.; Qin, Z.-H. Beclin 1, Bcl-2 and Autophagy. In Autophagy: Biology and Diseases: Basic Science; Qin, Z.-H., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 109–126. ISBN 978-981-15-0602-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dlamini, M.B.; Gao, Z.; Hasenbilige; Jiang, L.; Geng, C.; Li, Q.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, J. The Crosstalk between Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Promoted ATF4-Mediated Mitophagy Induced by Hexavalent Chromium. Environ. Toxicol. 2021, 36, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shergalis, A.G.; Hu, S.; Bankhead, A.; Neamati, N. Role of the ERO1-PDI Interaction in Oxidative Protein Folding and Disease. Pharmacol. Amp Ther. 2020, 210, 107525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compton, S.R. Overview of Coronaviruses in Veterinary Medicine. Comp. Med. 2021, 71, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, G.; Lee, D.; Shin, S.; Lim, J.; Won, H.; Eo, Y.; Kim, C.-H.; Lee, C. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus: An Update Overview of Virus Epidemiology, Vaccines, and Control Strategies in South Korea. J. Vet. Sci. 2023, 24, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Yuan, H.; Pang, D.; Ouyang, H. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus: An Updated Overview of Virus Epidemiology, Virulence Variation Patterns and Virus–Host Interactions. Viruses 2022, 14, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Jin, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, X. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Infections Induce Autophagy in Vero Cells via ROS-Dependent Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress through PERK and IRE1 Pathways. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 253, 108959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, W.; Gan, S.; Du, J.; Zhou, X.; Fang, W.; Wang, X.; Song, H. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Activates PERK-ROS Axis to Benefit Its Replication in Vero E6 Cells. Vet. Res. 2023, 54, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

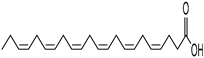

- Suo, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Fan, G.; Zhu, M.; Fan, B.; Yang, X.; Li, B. DHA and EPA Inhibit Porcine Coronavirus Replication by Alleviating ER Stress. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e01209-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-M.; Gabler, N.K.; Burrough, E.R. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Infection Induces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Unfolded Protein Response in Jejunal Epithelial Cells of Weaned Pigs. Vet. Pathol. 2022, 59, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Shi, X.; Yan, Y.; Yang, N.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q. GRAMD4 Regulates PEDV-Induced Cell Apoptosis Inhibiting Virus Replication via the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Pathway. Vet. Microbiol. 2023, 279, 109666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ma, M.; Shi, X.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, N.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q. The Novel Nsp9-Interacting Host Factor H2BE Promotes PEDV Replication by Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Apoptosis. Vet. Res. 2023, 54, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Ren, J.; Yang, G.; Jiang, C.; Dong, L.; Sun, Q.; Hu, Y.; Li, W.; He, Q. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus and Its Nsp14 Suppress ER Stress Induced GRP78. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Xu, J.; Duan, X.; Xu, X.; Li, P.; Cheng, L.; Zheng, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus ORF3 Protein Causes Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress to Facilitate Autophagy. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 235, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Ouyang, H.; Yuan, H.; Pang, D. Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus: An Update Review and Perspective. Viruses 2023, 15, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Knutson, T.P.; Rossow, S.; Saif, L.J.; Marthaler, D.G. Decline of Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus and Its Complex Evolutionary Relationship with Porcine Respiratory Coronavirus in the United States. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, D.; Yan, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Su, M.; Sun, D. Isolation and Characterization of a Porcine Transmissible Gastroenteritis Coronavirus in Northeast China. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 611721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, M.; Fu, F.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Feng, L.; Liu, P. The PERK Arm of the Unfolded Protein Response Negatively Regulates Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus Replication by Suppressing Protein Translation and Promoting Type I Interferon Production. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e00431-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xue, M.; Wu, P.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Wu, G.; Liu, P.; Wang, K.; Xu, W.; Feng, L. Coronavirus Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus Antagonizes the Antiviral Effect of the microRNA miR-27b via the IRE1 Pathway. Sci. China Life Sci. 2022, 65, 1413–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Chang, R.; Tong, D.; Xu, X. Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus N Protein Causes Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, up-Regulates Interleukin-8 Expression and Its Subcellular Localization in the Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cell. Res. Vet. Sci. 2018, 119, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpa, F.; Sanna, D.; Azzena, I.; Cossu, P.; Giovanetti, M.; Benvenuto, D.; Coradduzza, E.; Alexiev, I.; Casu, M.; Fiori, P.L.; et al. Update on the Phylodynamics of SADS-CoV. Life 2021, 11, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.; Zhou, L.; Shi, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D.; Feng, T.; Zeng, M.; Chen, J.; et al. Autophagy Is Induced by Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus through the Cellular IRE1-JNK-Beclin 1 Signaling Pathway after an Interaction of Viral Membrane-Associated Papain-like Protease and GRP78. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, J.; Zhou, C.; Chen, B.; Fang, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L. A Review of SARS-CoV2: Compared with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 628370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesheh, M.M.; Hosseini, P.; Soltani, S.; Zandi, M. An Overview on the Seven Pathogenic Human Coronaviruses. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zeng, X.; He, B.; Cheng, W. Structural Biology of SARS-CoV-2: Open the Door for Novel Therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaban, M.S.; Müller, C.; Mayr-Buro, C.; Weiser, H.; Meier-Soelch, J.; Albert, B.V.; Weber, A.; Linne, U.; Hain, T.; Babayev, I.; et al. Multi-Level Inhibition of Coronavirus Replication by Chemical ER Stress. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.-J.; Ha, D.P.; Machida, K.; Lee, A.S. The Stress-Inducible ER Chaperone GRP78/BiP Is Upregulated during SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Acts as a pro-Viral Protein. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puzyrenko, A.; Jacobs, E.R.; Sun, Y.; Felix, J.C.; Sheinin, Y.; Ge, L.; Lai, S.; Dai, Q.; Gantner, B.N.; Nanchal, R.; et al. Pneumocytes Are Distinguished by Highly Elevated Expression of the ER Stress Biomarker GRP78, a Co-Receptor for SARS-CoV-2, in COVID-19 Autopsies. Cell Stress Chaperones 2021, 26, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Castillo, V.; Espinoza, C.R.; Tindle, C.; Fonseca, A.G.; Dan, J.M.; Katkar, G.D.; Das, S.; Sahoo, D.; Ghosh, P. COVID-19 Lung Disease Shares Driver AT2 Cytopathic Features with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. eBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.U.G.; Bojkova, D.; Shumliakivska, M.; Luxán, G.; Nicin, L.; Aslan, G.S.; Milting, H.; Kandler, J.D.; Dendorfer, A.; Heumueller, A.W.; et al. Increased Susceptibility of Human Endothelial Cells to Infections by SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2021, 116, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wen, Y.-Z.; Huang, Z.-L.; Shen, X.; Wang, J.-H.; Luo, Y.-H.; Chen, W.-X.; Lun, Z.-R.; Li, H.-B.; Qu, L.-H.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Causes a Significant Stress Response Mediated by Small RNAs in the Blood of COVID-19 Patients. Mol. Ther.—Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echavarría-Consuegra, L.; Cook, G.M.; Busnadiego, I.; Lefèvre, C.; Keep, S.; Brown, K.; Doyle, N.; Dowgier, G.; Franaszek, K.; Moore, N.A.; et al. Manipulation of the Unfolded Protein Response: A Pharmacological Strategy against Coronavirus Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.C.; Renner, D.M.; Silva, D.; Yang, D.; Parenti, N.A.; Medina, K.M.; Nicolaescu, V.; Gula, H.; Drayman, N.; Valdespino, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Diverges from Other Betacoronaviruses in Only Partially Activating the IRE1α/XBP1 Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Pathway in Human Lung-Derived Cells. mBio 2022, 13, e02415-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolini, D.; Stabile, A.M.; Vacca, C.; Pistilli, A.; Rende, M.; Gioiello, A.; Cruciani, G.; Galli, F. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and NF-kB Activation in SARS-CoV-2 Infected Cells and Their Response to Antiviral Therapy. IUBMB Life 2022, 74, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, J.M.; Den Hartigh, A.B.; Jackson, S.M.; Tronco, A.R.; Fink, S.L. The Unfolded Protein Response Components IRE1α and XBP1 Promote Human Coronavirus Infection. mBio 2023, 14, e00540-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramaniam, A.; Tedbury, P.R.; Mwangi, S.M.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Merlin, D.; Gracz, A.D.; He, P.; Sarafianos, S.G.; Srinivasan, S. SARS-CoV-2 Induces Epithelial-Enteric Neuronal Crosstalk Stimulating VIP Release. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamberger, C.; Pankow, S.; Martínez-Bartolomé, S.; Diedrich, J.K.; Park, R.S.K.; Yates, J.R. Analysis of the Tropism of SARS-CoV-2 Based on the Host Interactome of the Spike Protein. J. Proteome Res. 2023, 22, 3742–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waisner, H.; Grieshaber, B.; Saud, R.; Henke, W.; Stephens, E.B.; Kalamvoki, M. SARS-CoV-2 Harnesses Host Translational Shutoff and Autophagy To Optimize Virus Yields: The Role of the Envelope (E) Protein. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e03707-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasy, K.M.; Davies, J.P.; Plate, L. Comparative Host Interactomes of the SARS-CoV-2 Nonstructural Protein 3 and Human Coronavirus Homologs. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2021, 20, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.P.; Sivadas, A.; Keller, K.R.; Roman, B.K.; Wojcikiewicz, R.J.H.; Plate, L. Expression of SARS-CoV-2 Nonstructural Proteins 3 and 4 Can Tune the Unfolded Protein Response in Cell Culture. J. Proteome Res. 2024, 23, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; He, S.; Deng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Sun, J.; Zhao, W.; Guo, Y.; Yin, Z.; Li, D.; et al. Comprehensive Insights into the Catalytic Mechanism of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome 3C-Like Protease and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome 3C-Like Protease. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5871–5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, P.; Fan, W.; Ma, X.; Lin, R.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jia, X.; Bi, Y.; Feng, X.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Nonstructural Protein 6 Triggers Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Autophagy to Degrade STING1. Autophagy 2023, 19, 3113–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.; Yu, X.; Zhou, C. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a Induces Incomplete Autophagy via the Unfolded Protein Response. Viruses 2021, 13, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keramidas, P.; Papachristou, E.; Papi, R.M.; Mantsou, A.; Choli-Papadopoulou, T. Inhibition of PERK Kinase, an Orchestrator of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), Significantly Reduces Apoptosis and Inflammation of Lung Epithelial Cells Triggered by SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a Protein. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Pan, T.; Long, X.; Sun, Q.; Wang, P.-H.; Li, X.; Kuang, E. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a Induces RETREG1/FAM134B-Dependent Reticulophagy and Triggers Sequential ER Stress and Inflammatory Responses during SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Autophagy 2022, 18, 2576–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruner, H.N.; Zhang, Y.; Shariati, K.; Yiv, N.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hejtmancik, J.F.; McManus, M.T.; Tharp, K.; Ku, G. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3A Interacts with the Clic-like Chloride Channel-1 ( CLCC1 ) and Triggers an Unfolded Protein Response. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Cruz-Cosme, R.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Tang, Q.; Zhao, R.Y. Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a Elicits Heightened Cytopathic Effects despite Robust ER-Associated Degradation. mBio 2024, 15, e03030-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Fu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, F.; Rao, J.; Xiao, X.; Sun, X.; Jin, H.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Ubiquitination of SARS-CoV-2 ORF7a Prevents Cell Death Induced by Recruiting BclXL To Activate ER Stress. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e01509-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiu, Z.; Feng, N.; Sun, W.; Li, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF8 Protein Induces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-like Responses and Facilitates Virus Replication by Triggering Calnexin: An Unbiased Study. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e00011-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, F.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF8 Reshapes the ER through Forming Mixed Disulfides with ER Oxidoreductases. Redox Biol. 2022, 54, 102388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, J.; Li, L.; Lv, X.; Gao, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, A.; Jiang, T. Integrated Interactome and Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Key Host Factors Critical for SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Virol. Sin. 2023, 38, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, F.; Dzakah, E.E.; Wang, H.; Tang, S. The ORF8 Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Induced Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Mediated Immune Evasion by Antagonizing Production of Interferon Beta. Virus Res. 2021, 296, 198350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Cai, K.; Li, J.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, R.; Xiao, H.; Xu, C.; Hu, B.; Qin, Y.; Ding, B. Coronavirus Subverts ER-Phagy by Hijacking FAM134B and ATL3 into P62 Condensates to Facilitate Viral Replication. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuiyan, M.S.A.; Sarker, S.; Amin, Z.; Rodrigues, K.F.; Saallah, S.; Shaarani, S.M.; Siddiquee, S. Infectious Bronchitis Virus (Gammacoronavirus) in Poultry: Genomic Architecture, Post-Translational Modifications, and Structural Motifs. Poultry 2023, 2, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, X.; Yin, Z. Current Knowledge on Infectious Bronchitis Virus Non-Structural Proteins: The Bearer for Achieving Immune Evasion Function. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 820625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G. Key Aspects of Coronavirus Avian Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Pathogens 2023, 12, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinteros, J.; Noormohammadi, A.; Lee, S.; Browning, G.; Diaz-Méndez, A. Genomics and Pathogenesis of the Avian Coronavirus Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Aust. Vet. J. 2022, 100, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.S.; Liu, D.X. The ER Stress Sensor IRE1 and MAP Kinase ERK Modulate Autophagy Induction in Cells Infected with Coronavirus Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Virology 2019, 533, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.C.; Li, S.; Yuan, L.X.; Chen, R.A.; Liu, D.X.; Fung, T.S. Induction of the Proinflammatory Chemokine Interleukin-8 Is Regulated by Integrated Stress Response and AP-1 Family Proteins Activated during Coronavirus Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.Q.; Fang, S.; Yuan, Q.; Huang, M.; Chen, R.A.; Fung, T.S.; Liu, D.X. N-Linked Glycosylation of the Membrane Protein Ectodomain Regulates Infectious Bronchitis Virus-Induced ER Stress Response, Apoptosis and Pathogenesis. Virology 2019, 531, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Yuan, L.; Dai, G.; Chen, R.A.; Liu, D.X.; Fung, T.S. Regulation of the ER Stress Response by the Ion Channel Activity of the Infectious Bronchitis Coronavirus Envelope Protein Modulates Virion Release, Apoptosis, Viral Fitness, and Pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-R.; Park, J.; Lee, K.-K.; Jeoung, H.-Y.; Lyoo, Y.S.; Park, S.-C.; Park, C.-K. Genetic Characterization and Evolution of Porcine Deltacoronavirus Isolated in the Republic of Korea in 2022. Pathogens 2023, 12, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, C. An Updated Review of Porcine Deltacoronavirus in Terms of Prevalence, Pathogenicity, Pathogenesis and Antiviral Strategy. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 811187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, P.; Tian, L.; Zhang, H.; Xia, S.; Ding, T.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, J.; Ren, J.; Fang, L.; Xiao, S. Induction and Modulation of the Unfolded Protein Response during Porcine Deltacoronavirus Infection. Vet. Microbiol. 2022, 271, 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureda, A.; Alizadeh, J.; Nabavi, S.F.; Berindan-Neagoe, I.; Cismaru, C.A.; Jeandet, P.; Łos, M.J.; Clementi, E.; Nabavi, S.M.; Ghavami, S. Endoplasmic Reticulum as a Potential Therapeutic Target for Covid-19 Infection Management? Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 882, 173288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, A.C.; Mitchell, H.D.; Gralinski, L.E.; Kyle, J.E.; Burnum-Johnson, K.E.; Lam, M.; Fulcher, M.L.; West, A.; Smith, R.D.; Randell, S.H.; et al. Unfolded Protein Response Inhibition Reduces Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-Induced Acute Lung Injury. mBio 2021, 12, e01572-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, H.; Shuai, H.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wen, L.; Huang, X.; Hu, B.; Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Yoon, C.; et al. Targeting Highly Pathogenic Coronavirus-Induced Apoptosis Reduces Viral Pathogenesis and Disease Severity. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf8577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Li, Z.; Xu, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, R.; Lu, H.; Lan, Y.; Zhao, K.; He, H.; et al. The PERK/PKR-eIF2α Pathway Negatively Regulates Porcine Hemagglutinating Encephalomyelitis Virus Replication by Attenuating Global Protein Translation and Facilitating Stress Granule Formation. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e01695-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhande, A.S.; Devarajan, P.V. A Review on Possible Mechanistic Insights of Nitazoxanide for Repurposing in COVID-19. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 891, 173748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.C.; Yang, D.; Nicolaescu, V.; Best, T.J.; Gula, H.; Saxena, D.; Gabbard, J.D.; Chen, S.-N.; Ohtsuki, T.; Friesen, J.B.; et al. Cannabidiol Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Replication through Induction of the Host ER Stress and Innate Immune Responses. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabi6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pringle, E.S.; Duguay, B.A.; Bui-Marinos, M.P.; Mulloy, R.P.; Landreth, S.L.; Desireddy, K.S.; Dolliver, S.M.; Ying, S.; Caddell, T.; Tooley, T.H.; et al. Thiopurines Inhibit Coronavirus Spike Protein Processing and Incorporation into Progeny Virions. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, D.P.; Shin, W.-J.; Hernandez, J.C.; Neamati, N.; Dubeau, L.; Machida, K.; Lee, A.S. GRP78 Inhibitor YUM70 Suppresses SARS-CoV-2 Viral Entry, Spike Protein Production and Ameliorates Lung Damage. Viruses 2023, 15, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Czinn, S.J.; Reiter, R.J.; Blanchard, T.G. Crosstalk between Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Anti-Viral Activities: A Novel Therapeutic Target for COVID-19. Life Sci. 2020, 255, 117842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).