Paternal Finasteride Treatment Can Influence the Testicular Transcriptome Profile of Male Offspring—Preliminary Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.1.1. The Parental Generation

2.1.2. The Filial Generation

2.2. Microarrays Analysis

2.2.1. RNA Isolation

2.2.2. Affymetrix GeneChip Microarray and Data Analysis

3. Results

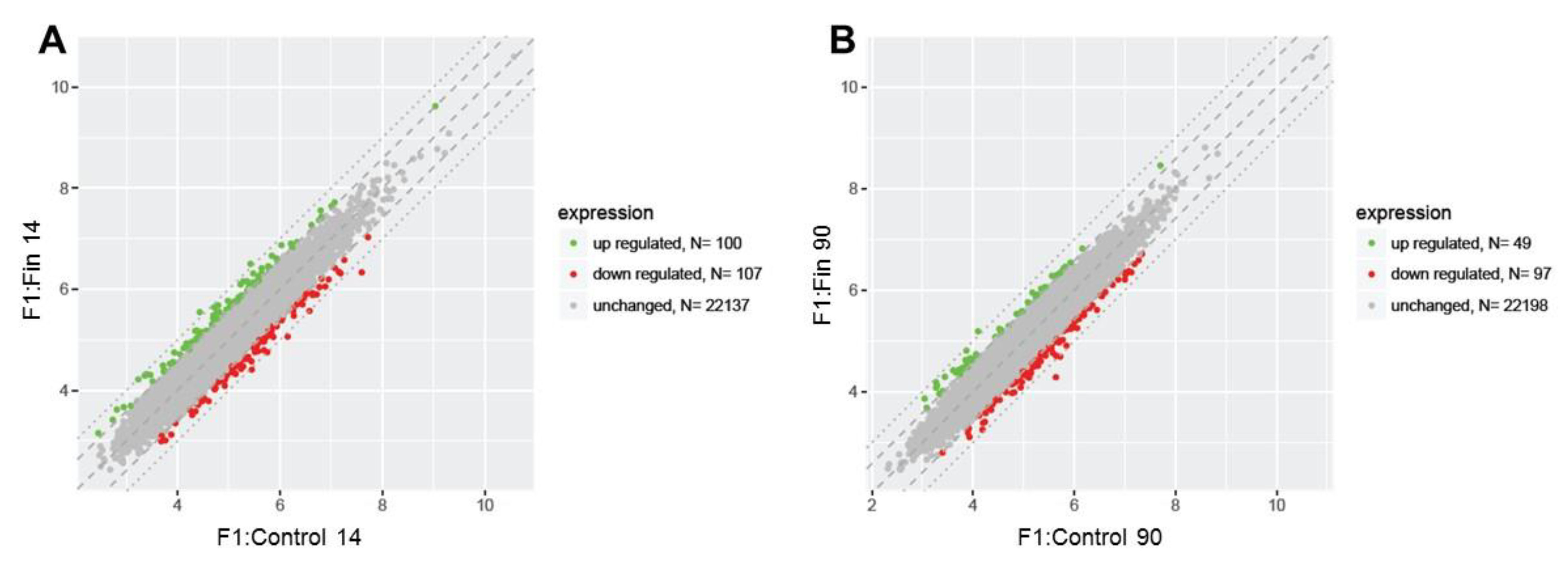

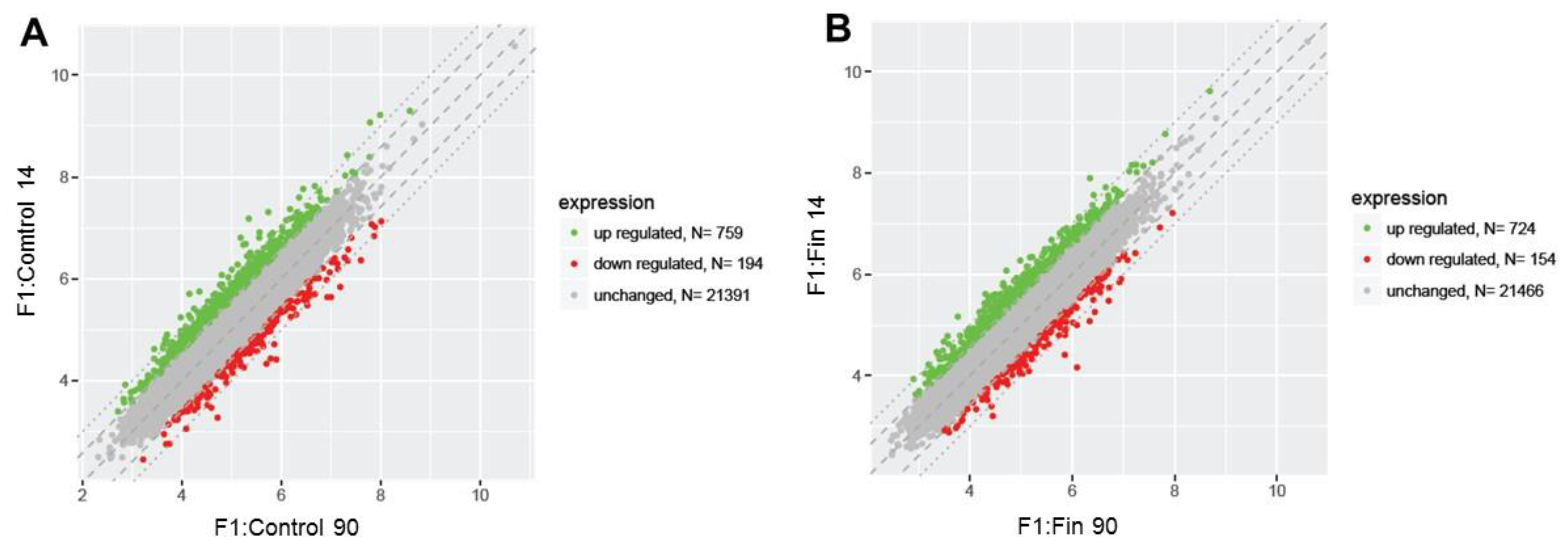

3.1. Differential Gene Expression Profiles

3.2. List of the Top 10 Changed Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patrão, M.T.C.C.; Silva, E.; Avellar, M.C.W. Androgens and the male reproductive tract: An overview of classical roles and current perspectives. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2009, 53, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.L.; Auchus, R.J. The Molecular Biology, Biochemistry, and Physiology of Human Steroidogenesis and Its Disorders. Endocr. Rev. 2011, 32, 81–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratis, K.; O’Donnell, L.; Ooi, G.T.; McLachlan, R.I.; Robertson, D.M. Enzyme assay for 5α-reductase Type 2 activity in the presence of 5α-reductase Type 1 activity in rat testis. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000, 75, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, B.W.; Levy, M.A.; Holt, D.A. Inhibitor of steroid 5-reductase in benign prostatic hyperplasia, male pat-tern baldness and acne. Trends Pharm. Sci. 1989, 10, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Li, F.; Ando, M.; Fujisawa, M. Finasteride-associated male infertility. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1786.e9–1786.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, K.D. The Finasteride Male Pattern Hair Loss Group Study. Long term (5-year) multinational experience with finas-teride 1 mg in the treatment of men with androgenic alopecia. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2002, 12, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.K.; Charrette, A. The efficacy and safety of 5α-reductase inhibitors in androgenetic alopecia: A network meta-analysis and benefit–risk assessment of finasteride and dutasteride. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2013, 25, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Takeda, A. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of finasteride 1 mg in 3177 Japanese men with androge-netic alopecia. J Dermatol. 2012, 39, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gur, S.; Kadowitz, P.J.; Hellstrom, W.J. Effects of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors on erectile function, sexual desire and ejaculation. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2012, 12, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzer, C.A.; Jacobs, A.R.; Iqbal, F. Persistent Sexual, Emotional, and Cognitive Impairment Post-Finasteride. Am. J. Men’s Health 2014, 9, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amory, J.K.; Wang, C.; Swerdloff, R.S.; Anawalt, B.D.; Matsumoto, A.M.; Bremner, W.J.; Walker, S.E.; Haber-er, L.J.; Clark, R.V. The effect of 5a-re¬ductase inhibition with dutasteride and finasteride on semen parameters and serum hormones in healthy men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 1659–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Binsaleh, S.; Lo, K.; Järvi, K. Propecia-induced spermatogenic failure: A report of two cases. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 90, 849.e17–849.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwig, M.S.; Kolukula, S. Persistent Sexual Side Effects of Finasteride for Male Pattern Hair Loss. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 1747–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwig, M.S. Depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts among former users of finasteride with persistent sexual side effects. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 1220–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, H.Y.V.; Zini, A. Finasteride-induced secondary infertility associated with sperm DNA damage. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 2125.e13–2125.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şalvarci, A.; Istanbulluoglu, O. Secondary infertility due to use of low-dose finasteride. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2012, 45, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collodel, G.; Scapigliati, G.; Moretti, E. Spermatozoa and Chronic Treatment with Finasteride: A TEM and FISH Study. Arch. Androl. 2007, 53, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Post-Finasteride Syndrome Foundation. Global Public Health Advisory–US National Institutes of Health Recognises Post-Finasteride Syndrome. 2015. Available online: us5.campaign-archive2.com/?u=644fb8b633594fee188a85091&id=9cea0753a4&e=5459eb9419 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- National Institutes of Health Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. Adverse Events of 5-Alpha-Reductase Inhibitors. 2015. Available online: http://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/gard/12407/post-finasteride-syndrome/resources/1 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Prahalada, S.; Tarantal, A.F.; Harris, G.S.; Ellsworth, K.P.; Clarke, A.P.; Skiles, G.L.; MacKenzie, K.I.; Kruk, L.F.; Ablin, D.S.; Cukierski, M.A.; et al. Effects of finasteride, a type 2 5-alpha reductase inhibitor, on fetal development in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Teratology 1997, 55, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, C.J.; Barlow, N.J.; Turner, K.J.; Wallace, D.G.; Foster, P.M.D. Effects of in Utero Exposure to Finasteride on Androgen-Dependent Reproductive Development in the Male Rat. Toxicol. Sci. 2003, 74, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Martinelli, M.; Luppi, S.; Bello, L.L.; De Santis, M.; Skerk, K.; Zito, G. Finasteride and fertility: Case report and review of the literature. J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD 2012, 11, 1511–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, K.H.; Shin, J.; Hong, S.C.; Han, J.Y.; Lee, E.H.; Lee, J.S.; Oh, M.J.; Kim, H.J. Pregnancy Outcomes with Paternal Exposure to Finasteride, a Synthetic 5-Alpha-Reductase Inhibitor: A Case Series. J. Clin. Toxicol. 2015, 5, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolasa-Wolosiuk, A.; Misiakiewicz-Has, K.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I.; Gutowska, I.; Wiszniewska, B. Androgen levels and apoptosis in the testis during postnatal development of finasteride-treated male rat offspring. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2015, 53, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebensperger, L.A. Strategies and counterstrategies to infanticide in mammals. Biol. Rev. 2007, 73, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K.P.; Foster, W.G. Key Developments in Endocrine Disrupter Research and Human Health. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2008, 11, 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowin, P.A.; Foster, P.M.D.; Risbridger, G.P. Endocrine disruption in the male. In Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals. From Basic Research to Clinical Pratice; Gore, A.C., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lettieri, G.; D’Agostino, G.; Mele, E.; Cardito, C.; Esposito, R.; Cimmino, A.; Giarra, A.; Trifuoggi, M.; Raimondo, S.; Notari, T.; et al. Discovery of the Involvement in DNA Oxidative Damage of Human Sperm Nuclear Basic Proteins of Healthy Young Men Living in Polluted Areas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettieri, G.; Marra, F.; Moriello, C.; Prisco, M.; Notari, T.; Trifuoggi, M.; Giarra, A.; Bosco, L.; Montano, L.; Piscopo, M. Molecular Alterations in Spermatozoa of a Family Case Living in the Land of Fires. A First Look at Possible Transgenerational Effects of Pollutants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, K.; Warita, K.; Tanida, T.; Sugawara, T.; Kitagawa, H.; Hoshi, N. Dose Paternal Exposure to 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-Dioxin (TCDD) affect the Sex Ratio of Offspring? J. Veter. Med. Sci. 2007, 69, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocarelli, P.; Gerthoux, P.M.; Ferrari, E.; Patterson, D.G.; Kieszak, S.M.; Brambilla, P.; Vincoli, N.; Signorini, S.; Tramacere, P.; Carreri, V.; et al. Paternal concentrations of dioxin and sex ratio of offspring. Lancet 2000, 355, 1858–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.J.; Amirova, Z.; Carrier, G. Sex ratios of children of Russian pesticide producers exposed to dioxin. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, A699–A701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anway, M.D.; Memon, M.A.; Uzumcu, M.; Skinner, M.K. Transgenerational Effect of the Endocrine Disruptor Vinclozolin on Male Spermatogenesis. J. Androl. 2006, 27, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolasa, A.; Marchlewicz, M.; Wenda-Różewicka, L.; Wiszniewska, B. DHT deficiency perturbs the integrity of the rat seminiferous epithelium by disrupting tight and adherens junctions. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2011, 49, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashby, J.; Tinwell, H.; Odum, J.; Lefevre, P. Natural variability and the influence of concurrent control values on the detection and interpretation of low-dose or weak endocrine toxicities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Kearbey, J.D.; Nair, V.A.; Chung, K.; Parlow, A.F.; Miller, D.D.; Dalton, J.T. Comparison of the pharmacological effects of a novel selective androgen receptor modulator, the 5alpha-reductase inhibitor finasteride, and the anti-androgen hydroxyl flutamide in intact rats: New approach for benign prostate hyperplasia. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 5420–5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clermont, Y.; Perey, B. Quantitative study of the cell population of the seminiferous tubules in immature rats. Am. J. Anat. 1957, 100, 241–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Enquist, L.; Dulac, C. Olfactory Inputs to Hypothalamic Neurons Controlling Reproduction and Fertility. Cell 2005, 123, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opatova, P. Peak fertility. In Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behaviour; Jennifer Vonk, J., Shackelford, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spehr, M.; Schwane, K.; Riffell, J.A.; Zimmer, R.K.; Hatt, H. Odorant receptors and olfactory-like signaling mechanisms in mammalian sperm. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2006, 250, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, M.; Libert, F.; Schurmans, S.; Schiffmann, S.; Lefort, A.; Eggerickx, D.; Ledent, C.; Mollereau, C.; Gérard, C.; Perret, J.; et al. Expression of members of the putative olfactory receptor gene family in mammalian germ cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 1992, 355, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderhaeghen, P.; Schurmans, S.; Vassart, G.; Parmentier, M. Olfactory receptors are displayed on dog mature sperm cells. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 123, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Rogers, M.; Tian, H.; Zou, D.-J.; Liu, J.; Ma, M.; Shepherd, G.M.; Firestein, S.J. High-throughput microarray detection of olfactory receptor gene expression in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14168–14173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderhaeghen, P.; Schurmans, S.; Vassart, G.; Parmentier, M. Specific Repertoire of Olfactory Receptor Genes in the Male Germ Cells of Several Mammalian Species. Genomics 1997, 39, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spehr, M.; Gisselmann, G.; Poplawski, A.; Riffell, J.A.; Wetzel, C.H.; Zimmer, R.K.; Hatt, H. Identification of a Testicular Odorant Receptor Mediating Human Sperm Chemotaxis. Science 2003, 299, 2054–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviano, G.; Zuccarello, D.; Menegazzo, M.; Perilli, L.; Marioni, G.; Frigo, A.C.; Staffieri, A.; Foresta, C. Human olfactory sensitivity for bourgeonal and male infertility: A preliminary investigation. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2013, 270, 3079–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djahanbakhch, O.; Ezzati, M.; Saridogan, E. Physiology and pathophysiology of tubal transport: Ciliary beat and muscular contractility, relevance to tubal infertility, recent research, and future directions. In The Fallopian Tube in Infertility and IVF Practice; Bahathiq, A.O.S., Tan, S.L., Ledger, W.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.; Bahat, A.; Gakamsky, A.; Girsh, E.; Katz, N.; Giojalas, L.; Tur-Kaspa, I.; Eisenbach, M. Human sperm chemotaxis: Both the oocyte and its surrounding cumulus cells secrete sperm chemoattractants. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spehr, M.; Schwane, K.; Riffell, J.A.; Barbour, J.; Zimmer, R.K.; Neuhaus, E.; Hatt, H. Particulate Adenylate Cyclase Plays a Key Role in Human Sperm Olfactory Receptor-mediated Chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 40194–40203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R. Physiology of the Graafian Follicle and Ovulation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 1–397. [Google Scholar]

- Olaniyan, O.T.; Dare, A.; Okotie, G.E.; Adetunji, C.O.; Ibitoye, B.O.; Eweoya, O.; Dare, J.B.; Okoli, B.J. Ovarian odorant-like biomolecules in promoting chemotaxis behavior of spermatozoa olfactory receptors during migration, maturation, and fertilization. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2021, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karteris, E.; Zervou, S.; Pang, Y.; Dong, J.; Hillhouse, E.W.; Randeva, H.S. Progesterone signaling in human my-ometrium through two novel membrane G protein-coupled receptors: Potential role in functional progesterone withdrawal at term. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Ho, P.; Yeung, W.S. Effects of human follicular fluid on the capacitation and motility of human spermatozoa. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 73, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviano, G.; Zuccarello, D.; Frasson, G.; Scarpa, B.; Nardello, E.; Foresta, C. Olfactory sensitivity and sexual desire in young adult and elderly men: An introductory investigation. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2013, 27, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottaviano, G.; Marioni, G.; Frasson, G.; Zuccarello, D.; Marchese-Ragona, R.; Staffieri, C. Olfactory threshold for bourgeonal and sexual desire in young adult males. Med. Hypotheses 2015, 84, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, T.M.; Sehgal, P.D.; Johnson, K.A.; Pier, T.; Bruskewitz, R.C.; Ricke, W.A.; Huang, W. Finasteride treat-ment alters tissue specific androgen receptor expression in prostate tissues. Prostate 2014, 74, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Loreto, C.; La Marra, F.; Mazzon, G.; Belgrano, E.; Trombetta, C.; Cauci, S. Immunohistochemical Evaluation of Androgen Receptor and Nerve Structure Density in Human Prepuce from Patients with Persistent Sexual Side Effects after Finasteride Use for Androgenetic Alopecia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchin, E.; De Mattia, E.; Mazzon, G.; Cauci, S.; Trombetta, C.; Toffoli, G. A Pharmacogenetic Survey of Androgen Receptor (CAG)N and (GGN)N Polymorphisms in Patients Experiencing Long Term Side Effects after Finasteride Discontinuation. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2014, 29, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cauci, S.; Chiriacò, G.; Cecchin, E.; Toffoli, G.; Xodo, S.; Stinco, G.; Trombetta, C. Androgen Receptor (AR) Gene (CAG)n and (GGN)n Length Polymorphisms and Symptoms in Young Males With Long-Lasting Adverse Effects After Finasteride Use Against Androgenic Alopecia. Sex. Med. 2017, 5, e61–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kur, P.; Kolasa-Wołosiuk, A.; Grabowska, M.; Kram, A.; Tarnowski, M.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I.; Rzeszotek, S.; Piasecka, M.; Wiszniewska, B. The Postnatal Offspring of Finasteride-Treated Male Rats Shows Hyperglycaemia, Elevated Hepatic Glycogen Storage and Altered GLUT2, IR, and AR Expression in the Liver. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traish, A.M. The Post-finasteride Syndrome: Clinical Manifestation of Drug-Induced Epigenetics Due to Endocrine Disruption. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2018, 10, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechis, S.K.; Otsetov, A.G.; Ge, R.; Olumi, A.F. Personalized Medicine for the Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. J. Urol. 2014, 192, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, R.K.; Sellamuthu, R. Receptors in spermatozoa: Are andrology they real? J. Androl. 2006, 27, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, L.; Smith, L.B. Androgen receptor roles in spermatogenesis and infertility. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 29, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Comparison Group | Gene Symbol | Gene/Pseudogene Name and Its Major Characteristic/Function | Entrez Gene ID | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1:Fin 14 vs. F1:Control 14 | Olfr365 | olfactory receptor 365; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8VFT2; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405932 | 2.16 |

| Olfr814 | olfactory receptor 814; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q7TRH4; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405135 | 2.11 | |

| Ugt2b5 | UPD glucuronosyltransferase 2 family, (UGT); increase lipophilic substrates water solubility. Glucuronidation of steroid hormones. Cellular response to glucocorticoid, growth hormone, testosterone stimulus; estrogen metabolic process (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P08542; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 266685 | 1.98 | |

| Olfr774 | olfactory receptor 774; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q7TRI5; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405233 | 1.91 | |

| Vmn1r211 | vomeronasal 1 receptor 211; G-protein-coupled receptor. Pheromone receptor activity, pheromone binding, response to pheromone (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8R266; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 494278 | 1.90 | |

| Olfr935 | olfactory receptor 935; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8VG16; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 288868 | 1.89 | |

| Olfr31 | olfactory receptor 31; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9Q3K2; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405403 | 1.85 | |

| Krtap19-9b | keratin associated protein 19-9B; hair keratin filaments are embedded in matrix, consisting of hair keratin-associated proteins (KRTAP), which are essential for the formation of a rigid and resistant hair shaft (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q99NG9; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 360626 | 1.83 | |

| Zfp874a | zinc finger protein 874a or regulator of sex-limitation candidate 15; DNA-binding transcription factor activity. Regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8BX23; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 286979 | 1.82 | |

| Glipr1l1 | GLI pathogenesis-related 1 like 1; binding of sperm to zona pellucida; a role in the binding between sperm and oocytes. Part of epididymosomes, membranous microvesicles which mediate the transfer of lipids and proteins to spermatozoa plasma membrane during epididymal maturation. Component of the CD9-positive microvesicles, found in the cauda region (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9DAG6; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 299783 | 1.80 | |

| Vmn2r23 | vomeronasal 2, receptor 23; G-protein-coupled receptor activity (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9PXI5; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 308303 | −1.78 | |

| Rln1 | relaxin 1; acts with estrogen to produce dilatation of the birth canal in many mammals. Hormone activity, signaling receptor binding. Modulation of G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway; developmental growth, mammary gland morphogenesis, negative regulation of apoptotic process, involved in nipple development, prostate gland growth, regulation of body fluid levels, regulation of cell population proliferation, regulation of nitric oxide-mediated signal transduction, spermatogenesis (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P01347; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 25616 | −1.78 | |

| Bod1 | biorientation of chromosomes in cell division 1; protein phosphatase inhibitor activity. Cell division, mitotic metaphase plate congression, mitotic sister chromatid biorientation and cohesion, centromeric, negative regulation of phosphoprotein phosphatase activity, protein localization to chromosome, centromeric region (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q6AYJ2, accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 287173 | −1.82 | |

| Olfr633 | olfactory receptor 633; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8VF02; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 404844 | −1.83 | |

| Olfr1112 | olfactory receptor 1112; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/A2ATA0; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405559 | −1.86 | |

| Krt17 | keratin 17—type I keratin; formation and maintenance of various skin appendages (by modulating TNF-alpha, Akt/mTOR, immune response in skin). Involved in tissue repair, a marker of epithelial ‘stem cells’. Constituent of cytoskeleton, hair follicle morphogenesis, intermediate filament-based process, keratinization, morphogenesis of epithelium, positive regulation of cell growth, hair follicle development, and translation (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q6IFU8, accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 287702 | −1.99 | |

| Oas1g | 2-5 oligoadenylate synthetase 1G; defense response to viruses, innate immune response, negative regulation of viral genome replication, regulation of ribonuclease activity (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q5MYX1; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 100910735 | −2.01 | |

| Dsg1c | desmoglein 1 gamma; component of intercellular desmosome junctions. Involved in homophilic cell adhesion via plasma membrane adhesion molecules. Calcium ion binding, gamma-catenin binding (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q7TSF0; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 291755 | −2.06 | |

| Akr1c19 | aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C19; enzymatic activity, including steroid dehydrogenase activity. Involved in steroid metabolic process. 90% identity with NAD-preferring dehydrogenase for 17-β-hydroxysteroids and 9-hydroxyprostaglandins (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/D3ZEL2; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 307096 | −2.13 | |

| Gm4340 | predicted gene 4340; RNA binding (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/L7N2C4; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 100043292 | −2.40 | |

| F1:Fin 90 vs. F1:Control 90 | Vmn1r103 | vomeronasal 1 receptor 103; pheromone receptor activity, response to pheromones (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/K7N6X7; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 100312735 | 2.13 |

| Olfr1109 | olfactory receptor 1109; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/A2AT96; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405557 | 1.92 | |

| Olfr1212 | olfactory receptor 1212; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q7TR08; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405579 | 1.89 | |

| Chil3 | chitinase-like 3; binds chitin and heparin. Has chemotactic activity. May play a role in inflammation and allergies. Enzymatic activity, chitin catabolic process, inflammatory response, polysaccharide catabolic process (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O35744; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 295351 | 1.80 | |

| Olfr1173 | olfactory receptor 1173; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q7TR24; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 404329 | 1.79 | |

| Vmn1r210 | vomeronasal 1 receptor 210; pheromone receptor activity, response to pheromones (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8R274; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 286957 | 1.77 | |

| Gm15056 | predicted gene 15056; lack of information (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O88242; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 100504014 | 1.76 | |

| Tmem161a | transmembrane protein 161A; cellular response to oxidative stress, cellular response to UV, negative regulation of intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway in response to DNA damage, positive regulation of DNA repair, response to retinoic acid (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/B1WC35; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 364535 | 1.75 | |

| Wdr83os | WD repeat domain 83 opposite strand (preferred name protein: Asterix); component of the complex that facilitates multi-pass membrane proteins insertion into membranes, including ER. Involved in organization of the ER. Calcium ion homeostasis, ERAD pathway, ER overload response, post-embryonic development (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q5U2X6; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 288925 | 1.72 | |

| Vmn1r50 | vomeronasal 1 receptor 50; G-protein coupled receptor, putative pheromone receptor implicated in the regulation of social and reproductive behavior. Pheromone receptor activity, response to pheromone, sensory perception of chemical stimulus (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9EP51; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 494267 | 1.71 | |

| Hist1h2bn | histone cluster 1, H2bn; transcription regulation, DNA repair, DNA replication, and chromosomal stability. DNA binding, identical protein binding, protein heterodimerization activity. Antibacterial and antimicrobial immune response, defense response to Gram-positive bacterium, innate immune response in mucosa, nucleosome assembly (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P10853; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 291157 | −1.77 | |

| Ptms | parathymosin; mediate immune function by blocking the effect of prothymosin alpha. Enzyme inhibitor activity, zinc ion binding, immune system processes (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P04550; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 83801 | −1.77 | |

| Mrgpra6 | MAS-related GPR, member A6—orphan receptor; G-protein-coupled receptor activity. A receptor for some neuropeptides, which are analgesic in vivo. Regulate nociceptor function and/or development, the sensation/modulation of pain (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q91ZC6; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 381886 | −1.78 | |

| Ormdl3 | ORM1-like 3; cellular sphingolipid homeostasis, ceramide metabolic process, motor behavior, myelination, negative regulation of B cell apoptotic process, ceramide biosynthetic process, serine C-palmitoyltransferase activity; positive regulation of autophagy, protein localization to nucleus; regulation of ceramide biosynthetic process, smooth muscle contraction, sphingolipid and sphingomyelin biosynthetic process (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q6QI25; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 360618 | −1.79 | |

| Spin2d | spindlin family, member 2D; methylated histone binding. Regulates cell cycle, transcription, DNA-templated, gamete generation (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/B1B0R2; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 100504429 | −1.81 | |

| Olfr1383 | olfactory receptor 1383; olfactory receptor, odorant binding. G-protein-coupled receptor, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q7TQT2; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 287232 | −1.91 | |

| Supt4a | suppressor of Ty 4A; regulates mRNA processing and transcription elongation, chromatin organization, mRNA processing, elongation, negative and positive regulation of transcription (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P63271; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 20922 | −1.91 | |

| Gm5132 | predicted gene 5132; DNA binding, protein heterodimerization activity. Chromatin silencing (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/L7MU04; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 333452 | −1.91 | |

| Rex2 | RNA Exonuclease 2 Homolog; 3′-to-5′ exonuclease specific for small single-stranded RNA and DNA oligomers. DNA repair, replication, and recombination, RNA processing, and degradation. Resistance of cells to UV-C-induced cell death. A role in cellular nucleotide recycling (https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=REXO2; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 104444 | −2.04 | |

| AF067061 | cDNA sequence AF0670; lack of information (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O70616; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 236546 | −2.55 | |

| F1:Control 90 vs. F1:Control 14 | Bod1 | biorientation of chromosomes in cell division 1; DNA binding, protein phosphatase 2A binding, protein phosphatase inhibitor activity, cellular response to DNA damage stimulus, DNA repair, negative regulation of phosphoprotein phosphatase activity, replication fork processing (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/E9Q6J5; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 287173 | 3.57 |

| AY358078 | cDNA sequence AY358078 (HN1-like protein); lack of information (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q6UY53; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 278676 | 3.09 | |

| Gm8995 | predicted gene 8995; lack of information (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8C9P2; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 668139 | 2.97 | |

| Klk1b5 | Kallikrein 1-related peptidase b5; enzymatic activity, acting on carbon–nitrogen (but not peptide) bonds, proteolysis, regulation of systemic arterial blood pressure, zymogen activation (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P15945; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 16622 | 2.94 | |

| Idi2 | isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase 2; enzymatic activity, metal ion binding, cholesterol biosynthetic process, isopentenyl diphosphate biosynthetic process, isopentenyl diphosphate metabolic process, negative regulation of cholesterol biosynthetic process (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8BFZ6; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 502143 | 2.70 | |

| Olfr1259 | olfactory receptor 1259; G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor, odorant binding, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8VEZ1; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 300581 | 2.64 | |

| Krt17 | keratin 17; described above. | 287702 | 2.64 | |

| Olfr331 | olfactory receptor 331; G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor, odorant binding, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q5NC44; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405033 | 2.55 | |

| Snora5c | small nucleolar RNA (snoRNAs), H/ACA box 5C; involved in RNA processing (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/677796; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | * | 2.50 | |

| C1rb | complement component 1, r subcomponent B; complement activation, classical pathway, innate immune response, zymogen activation, calcium ion binding, identical protein binding, serine-type endopeptidase activity (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8CFG9; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 667277 | 2.43 | |

| Trbj1-6 | T cell receptor beta joining 1-6; participates in the antigen recognition. Initiates three major signaling pathways, the calcium, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase, and the nuclear factor NF-kappa-B (NF-kB) pathways (https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=TRBJ1-6; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 100125253 | −2.18 | |

| Vmn1r211 | vomeronasal 1 receptor 211; described above. | 171277 | −2.21 | |

| Vmn2r99 | vomeronasal 2, receptor 99; G-protein-coupled receptor activity (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/H3BK37; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 680992 | −2.36 | |

| Gm10503 | predicted gene 10503; lack of information (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q3UUQ9; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 100038436 | −2.44 | |

| Rpl35 | ribosomal protein L35; component of the large ribosomal subunit. mRNA binding, ribonucleoprotein complex binding, structural constituent of ribosome, cellular response to UV-B, maturation of transcript, translation (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P17078; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 296709 | −2.54 | |

| Olfr365 | olfactory receptor 365; G-protein-coupled receptor activity. Olfactory receptor, odorant binding, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8VFT2; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405932 | −2.55 | |

| Apol9a | apolipoprotein L 9a; lipid binding and transport, lipoprotein metabolic process (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q5XIB6; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 503164 | −2.57 | |

| Ssxb2 | synovial sarcoma, X member B, breakpoint 2. A modulator of transcription, DNA-templated (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8C5Z3; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 387132 | −2.58 | |

| Gm5592 | predicted gene 5592; lack of information (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q3V0A6; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 434172 | −2.72 | |

| LOC102638448 | 40S ribosomal protein S7-like; lack of information (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/?query=LOC102638448&sort=score; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 102638448 | −2.80 | |

| F1:Fin 90 vs. F1:Fin 14 | Snora5c | small nucleolar RNA, H/ACA box 5C; Described above (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/677796; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | * | 2.93 |

| 5430402E10Rik | RIKEN cDNA 5430402E10 (odorant-binding protein 2); odorant binding, small molecule binding (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9D3N5; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 71351 | 2.63 | |

| Apol7b | apolipoprotein L 7b; lipid binding and transport, lipoprotein metabolic process (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/B1AQP7; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 278679 | 2.56 | |

| Vmn2r3 | vomeronasal 2, receptor 3; G-protein-coupled receptor activity, olfactory receptor activity (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/H3BJ88; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 502213 | 2.47 | |

| Igkv1-110 | immunoglobulin kappa variable 1-110; immune response (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/A0A0B4J1I0; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 381777 | 2.44 | |

| Olfr1253 | olfactory receptor 1253; G-protein-coupled receptor activity. Olfactory receptor, odorant binding, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/A2AUA2; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405091 | 2.32 | |

| 9030025P20Rik | RIKEN cDNA 9030025P20 gene; lack of information (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q3TV04; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 100041574 | 2.27 | |

| Gsdmc2 | gasdermin C2; constitutes the precursor of the pore-forming protein that causes membrane permeabilization and pyroptosis, binds to membrane lipids. Defense response to bacterium, intestinal epithelial cell development (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q2KHK6; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 331063 | 2.26 | |

| Cpq | carboxypeptidase Q; enzymatic activity, liberation of thyroxine hormone, metal ion binding, peptide catabolic process, proteolysis, tissue regeneration (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q6IRK9; accesse date: 24 June 2021) | 58952 | 2.25 | |

| LOC102642621 | uncharacterized LOC10264262; lack of information (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/?query=LOC102642621&sort=score; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | * | 2.23 | |

| Cyp2d9 | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily d, polypeptide 9; enzymatic activity. Oxidation, heme, iron ion binding, steroid hydroxylase activity, arachidonic acid metabolic process, exogenous drug catabolic process, organic acid metabolic process, xenobiotic metabolic process (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P11714; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 266684 | −2.08 | |

| Rln1 | relaxin 1; described above (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P01347; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 25616 | −2.10 | |

| Gm10503 | predicted gene 10503; described above (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q3UUQ9; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 100038436 | −2.11 | |

| Olfr890 | olfactory receptor 890; G-protein-coupled receptor activity. Olfactory receptor, odorant binding, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q7TRD9; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 405511 | −2.14 | |

| Gm9805 | predicted gene 9805; lack of information (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O88242; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 100534296 | −2.28 | |

| Olfr1251 | olfactory receptor 1251; G-protein-coupled receptor activity. Olfactory receptor, odorant binding, olfactory receptor activity. Sensory perception of smell (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q7TQZ3; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 300576 | −2.36 | |

| Gm5592 | predicted gene 5592; described above (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q3V0A6; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 434172 | −2.38 | |

| Zfp455 | zinc finger protein 455; regulation of transcription (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/G3V9J4; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 286979 | −2.41 | |

| Dsg1c | desmoglein 1 gamma. described above (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q7TSF0; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 291755 | −2.73 | |

| LOC102638448 | 40S ribosomal protein S7-like; described above (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/?query=LOC102638448&sort=score; accesse date: 24 June 2021). | 102638448 | −3.82 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kolasa, A.; Rogińska, D.; Rzeszotek, S.; Machaliński, B.; Wiszniewska, B. Paternal Finasteride Treatment Can Influence the Testicular Transcriptome Profile of Male Offspring—Preliminary Study. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 43, 868-886. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb43020062

Kolasa A, Rogińska D, Rzeszotek S, Machaliński B, Wiszniewska B. Paternal Finasteride Treatment Can Influence the Testicular Transcriptome Profile of Male Offspring—Preliminary Study. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2021; 43(2):868-886. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb43020062

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolasa, Agnieszka, Dorota Rogińska, Sylwia Rzeszotek, Bogusław Machaliński, and Barbara Wiszniewska. 2021. "Paternal Finasteride Treatment Can Influence the Testicular Transcriptome Profile of Male Offspring—Preliminary Study" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 43, no. 2: 868-886. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb43020062

APA StyleKolasa, A., Rogińska, D., Rzeszotek, S., Machaliński, B., & Wiszniewska, B. (2021). Paternal Finasteride Treatment Can Influence the Testicular Transcriptome Profile of Male Offspring—Preliminary Study. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 43(2), 868-886. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb43020062