Abstract

Pharmaceutical expenditures in ambulatory care rose rapidly in Europe in the 1990s and early 2000s. This was typically faster than other components of healthcare spending, leading to reforms to moderate future growth. A number of these centered on generic medicines with measures to lower reimbursed prices as well as enhance their prescribing and dispensing. The principal objective of this paper is to review additional measures that some European countries can adopt to further reduce reimbursed prices for generics. Secondly, potential approaches to address concerns with generics when they arise to maximize savings. Measures to enhance the prescribing of generics will also briefly be discussed. A narrative review of the extensive number of publications and associated references from the co-authors was conducted supplemented with known internal or web-based articles. In addition, health authority and health insurance databases, principally from 2001 to 2007, were analyzed to assess the impact of the various measures on price reductions for generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin vs. pre-patent loss prices, as well as overall efficiency in Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) and statin prescribing. The various initiatives generally resulted in considerable lowering of the prices of generics as well as specifically for generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin vs. pre-patent loss prices. At one stage in the UK, generic simvastatin was just 2% of the originator price. These measures also led to increased efficiency for PPI and statin prescribing with reimbursed expenditure for the PPIs and statins either falling or increasing at appreciably lower rates than increases in utilization. A number of strategies have also been introduced to address patient and physician concerns with generics to maximize savings. In conclusion, whilst recent reforms have been successful, European countries must continue learning from each other to fund increased volumes and new innovative drugs as resource pressures grow. Policies regarding generics and their subsequent impact on reimbursement and utilization of single sourced products will continue to play a key role to release valuable resources. However, there must continue to be strategies to address concerns with generics when they exist.

1. Introduction

Pharmaceutical expenditures have increased rapidly in recent years in Europe, typically rising at between 4% and 13% per annum [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. This is generally faster than other components of healthcare spending [6,10,11,12], similar to the US [13,14]. As a consequence, pharmaceutical expenditures in ambulatory care are now the largest or one of the largest cost components in this segment across a number of European countries [1,2,4,6,12]. In middle and lower income countries, expenditures on pharmaceuticals are also an appreciable component of expenditures, ranging from 20% to 60% of total spending on health [15].

European health authorities and health insurance organisations have instigated a number of reforms and initiatives in recent years to address this unsustainable growth. Many of the measures introduced have centred on policies surrounding generics, as they can provide high quality treatment [16] at lower costs, resulting in considerable savings [4,11,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

The various reforms and initiatives have led to lower reimbursed prices for generics and originators as well as interchangeable brands within pharmacologic or therapeutic classes [2,4,6,19,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. The reforms have also increased the first line prescribing and dispensing of generics where seen as standard treatment for the condition [1,4,6,11,12,17,19,27,28], the latter through, for instance, encouraging or mandating pharmacists to substitute less expensive generics in place of more expensive originators where pertinent, unless prohibited by physicians or health authorities [11,17,19,21,22,31]. Similar situations also occur in Asia. As an example, government physicians in Indonesia will soon be required to only prescribe generic drugs unless there are no generic alternatives available [32].

In 2006, generic medicines accounted for 42% of dispensed packs among 27 European countries, but only 18% of total pharmaceutical expenditures [33]. A recent analysis of 219 substances among the 27 Member States of the EU accounting for approximately 50% of prescription volumes calculated the market share of generics was approximately 30% at the end of the first year and 45% at the end of the second year [24]. Preferential co-payment policies for generics in the US among the insured population and seniors have also resulted in high utilisation of generics. As a result, generics account for approximately two thirds of prescriptions, but only 13% of costs [34,35].

There is appreciable variation in the utilisation of generics across Europe [36,37]. For example, there is still limited penetration of generics in Greece, accounting for only 11.6% of total pharmaceutical expenditures in 2006 [9]. There has also been appreciable differences in the reimbursed prices of generics across Europe [20,36,37], with prices of generics varying up to 36-fold across countries, depending on the molecule [20].

Pharmaceutical expenditures will continue to grow in Europe driven by demographic changes, rising patient expectations, stricter clinical targets and the continued launch of new premium priced drugs [10,24,38,39,40]. Consequently, further reforms are essential to maintain comprehensive and equitable healthcare in Europe without prohibitive increases in either taxes or health insurance premiums.

Key areas for learning for European countries include additional measures to further lower prices of multiple source products where pertinent. They also include measures to increase the prescribing and dispensing of generics [11,12,28,29]. There have though been concerns with the effectiveness and safety of generics [4,7,9,11,21,23,25,33,34,41,42,43,44,45], with some originator companies questioning the quality of generics as part of their marketing strategies to reduce post-patent loss sales erosion [24]. However concerns with generics generally only apply to a minority of situations [9,11,34,43]. This is endorsed by two recent comprehensive reviews comparing the outcomes between generics and originators for cardiovascular diseases and epilepsy [22,46]. The authors found no evidence in published trials that originator drugs had superior effectiveness and outcomes than different generic formulations. This included drugs with a narrow therapeutic index such as propafenone and warfarin [46]. Recent studies have also shown no increase in relapse rates with generic atypical antipsychotic drugs vs. originators apart from initial formulations of generic clozapine in the US [47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. There has also been concerns with confusion when patients are dispensed multiple branded generics each with different names, which can potentially lead to medication errors [11]. These issues must be addressed for health authorities and insurance companies to fully capitalise on future patent losses. This is especially important with estimated global sales of USD $100B per year over the next four years subject to patent losses [54].

Consequently, the principal objective of this paper is to review additional measures that European countries can adopt to further reduce reimbursed prices for multiple source products where pertinent. Secondly, review potential approaches that governments, health authorities and health insurance agencies could instigate to address any concerns with generics when they arise to maximise savings. Potential measures to further enhance the prescribing of generics will be briefly mentioned and discussed further in future papers as it is recognised this is equally important to enhance prescribing efficiency.

We hope this article will stimulate debate on future measures that could be introduced as payers struggle to provide comprehensive and equitable healthcare within finite budgets. The various initiatives may also be of interest to payers outside of Europe as well as to other key stakeholder groups.

2. Methodology

We conducted a narrative review of articles selected from the extensive number of publications and associated references from 17 co-authors concerned with generics. These were subsequently combined with published general reviews on generics as well as additional papers and articles known to the 17 co-authors concerned with initiatives to enhance prescribing efficiency such as web-based articles that had eluded the initial selection. Finally, a targeted literature review of English language papers was subsequently undertaken by one of the authors (B.G.) across chosen European countries where the initial approaches identified no pertinent peer reviewed publications. This involved searching PubMed, MEDLINE and EMBASE between 2000 and February 2010 using key words ‘generics’, ‘generic medicines’, ‘reforms’, ‘generic reforms’, ‘generic pricing’, ‘reference pricing’ and ‘generic substitution’ and the specific country. However, no additional papers were found for possible inclusion.

The same methodological approach was adopted when collating and reviewing papers that discuss reference pricing in a class, as well as different approaches adopted by health authorities to address patient and physician concerns with generics.

There has been no review of the quality of the papers included in this paper using for instance criteria developed by the Cochrane Collaboration [55]. This is because some of the references are from non-peer reviewed journals, internal health authority documents or web based articles. Nevertheless they have been included as they were typically written by payers or their advisers, which are the principal intended audience for this paper. Table 1A in the Appendix contains the definitions used in this paper.

The generics and classes chosen for more in-depth analysis were generic omeprazole and the Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)—Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) A02BC [56], and generic simvastatin and the HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins)—ATC group C10AA [56]. These two classes and products were chosen as:

- They are both high volume prescribing areas in ambulatory care;

- They contain a mixture of generics, originators and single sourced products in a class;

- They are typically the subject of initiatives within countries to enhance efficiency.

The price reductions for generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin were computed by comparing reimbursed prices per Defined Daily Dose (DDDs) in 2007 or later with originator prices in 2001 or before. These dates were chosen as generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin were typically launched after 2001 among Western European countries.

Only health authority or health insurance databases were used for the analyses in order to provide data on actual reimbursed payments for the various products in each of the two classes [36]. The sources of the administrative databases (covering all the patient population unless stated) included:

- Austria—Data Warehouse of the Federation of Austrian Social Insurance Institutions—HVB (98% of the population);

- England—Information Centre for Health and Social Care;

- Estonia—Estonian Health Insurance Fund;

- France—Medic'am database (CNAM-TS for salaried personnel covering 75% of the population);

- Germany—GAMSI-Database, the GKV Arzneimittel Schnell-Information covering all prescriptions paid by the Social Health Insurance Funds (approximately 90% of the population);

- Italy—OsMed database;

- Lithuania—Electronic database of the National Health Insurance Fund;

- Poland—National Health Fund database;

- Portugal—INFARMED (NHS) database covering approximately 75% of the population;

- Serbia—Republic of Serbia’s Health Insurance Fund database;

- Scotland—Prescribing Information System (PIS) from NHS National Services Scotland Corporate Warehouse;

- Spain—DMART (Catalan Health Service) database;

- Sweden—Apoteket AB (National Corporation of Swedish Pharmacies – monopoly up to 1 January 2010).

The concepts of ATC classification and DDDs were developed to facilitate comparisons in drug utilisation between countries [57,58]. The first comprehensive list of DDDs was first published in Norway in 1975, and has developed since then [59]. As a result, DDDs are now an internationally accepted method for comparing drug utilisation across countries especially where there are different pack sizes and possibly tablet strengths [59,60,61]. 2010 DDDs were used in line with recent recommendations [61].

There has been no allowance for inflation as we wanted to compute the actual impact of different policies on reimbursed prices/DDD of generics vs. originators over time based on the local currency. In addition, expenditure figures for the PPIs and statins are presented as percentage reductions or increases rather than actual changes in reimbursed prices or changes in overall reimbursed expenditure. This is because the extent of co-payments, wholesaler and pharmacy margins as well as taxes varies considerably across Europe. As a result, making direct expenditure comparisons difficult.

Finally, details of the reforms regarding the pricing policies for generics as well as interchangeable products in a class were taken from published sources and verified by the co-authors; alternatively, provided directly by the co-authors.

Sixteen European countries and regions have been included in this paper. These countries are: Austria, Estonia, France, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Poland, Serbia, Spain (Catalonia), Sweden, Turkey and the United Kingdom (England and Scotland). The countries were chosen to reflect differences in geography, epidemiology, financing of healthcare, available resources for healthcare, approaches to the pricing of generics, originators and single sourced products, as well as measures to enhance the prescribing of generics.

Where possible, expenditure figures have been quoted in Euros. Current exchange rates are €1 = 1.3 US$, 1.33 CAN$, 7.84 NOK, 9.63 SEK, 0.86 GB£ (3 May 2010).

We accept there are limitations with the study design. These include no linking of the indications and the actual doses prescribed to calculate Prescribed Daily Doses (PDD) [62], and reimbursed expenditure/PDD, as there was no access to prescribing databases. They also include the fact that no impact studies were undertaken as health authorities and health insurance agencies typically implemented a number of strategies between 2001 and 2007 to enhance prescribing efficiency making such analyses difficult to perform. In addition, most countries provided data on their total population.

3. Results

3.1. Pricing policies for generics and originals (general) and their impact

The chosen European countries have either instigated prescriptive pricing approaches for the molecule (generics and originators), let market forces drive down prices, or instigated a mixture of the two (Table 1). Table A1 (see Appendix) contains the definitions. Typically across Europe, market forces or mixed approaches appear to be the most popular methods to reduce the prices of generics [16,19,30]. Details of the different approaches are contained in Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4.

Table 1.

Different pricing approaches for generics and originators among exemplar European countries.

| Pricing approaches | Countries |

|---|---|

| Prescriptive pricing | France, Netherlands, Norway, Turkey |

| Market forces | Germany, Poland, Spain*, Sweden, United Kingdom |

| Mixed approach | Austria, Estonia, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Serbia |

*Spain is considering a prescriptive pricing policy for the first generic to accelerate access [63].

In Austria, the various initiatives surrounding generics and originator drugs have reduced the growth rate in ambulatory care pharmaceutical expenditure to between just under 2% to 6% per year from a baseline of 4% to 13% per year in the late 1990s and early 2000 [6]. In Catalonia, generics now account for 30% of the prescriptions by volume, helped by recent policies [12]. This is higher than a number of other regions in Spain.

In the United Kingdom (Table A3), the introduction of the ‘Manufacturer’ and ‘Wholesaler’ scheme in 2005 to increase transparency in the cost of goods, pricing of generics and discounts given to community pharmacists, led to an average 32.4% reduction in generic prices the first full year of introduction [64,65,66]. This led to a reduction of 2% in total pharmaceutical expenditure in the England and Wales the first full year following the introduction compared with the previous year [64,65]. At one stage, the reimbursed price of generic simvastatin was just 2% of the originator price [5]. The reimbursed price of generic risperidone was also just 2% of the originator price 29 months after its availability in December 2007—10% after six months [26]. Both provide examples to other European countries on potential prices for multiple source products. In addition in 2008, savings through increased prescribing efficiency were calculated at £364M in England alone [67]. This was enhanced by high International non-proprietary name (INN) prescribing currently at over 83% of overall prescriptions, rising to over 99% for certain generics [25,27,68].

In France (Table A4), overall annual savings from the instigation of the new pricing system for generics, combined with various measures to enhance the prescribing and dispensing of generics, was calculated at €1B in 2007 [4]. This was up from €500M in 2005 [4]. In 2008, additional savings were estimated at €905mn and €1bn in 2009 [69,70]. The savings in 2007 included compulsory price cuts as well as savings from the launch of new generics, which were estimated at €340M alone in 2006 [4]. These measures helped reduce the rate of increase in ambulatory care pharmaceutical expenditure in France in recent years to between 1% to 6% per annum [4]. This was considerably lower than annual rate of increase in hospital pharmaceutical expenditure, which was approximately 20% per annum during the same period [4].

In Sweden, prices of generics fell by 40% by the end of 2005 compared with 2002 following the instigation of compulsory generic substitution. The reimbursement agency (TLV) subsequently estimated total savings from the various measures, including compulsory generic substitution, to be €700M (>SEK6.97B) from 2002 to the end of 2005 [11]. Savings are likely to be greater in recent years with reimbursed prices for high volume ambulatory care generics in 2008 at between 4% to 13% of pre-patent originator prices, i.e. price reductions of 87% to 96% [11]. The various combined measures led to ambulatory care expenditure on non-specialised drugs actually stabilising in Stockholm County Council in recent years [11], with the overall increase in ambulatory care pharmaceutical expenditure across Sweden limited to just 1% to 3% per annum between 2003 and 2006 [5]. This compares with an average rate of 10% per year during the 1990s and early 2000s [5].

A recent ecological study conducted in Stockholm (Sweden) showed no significant differences in surrogate outcomes for hypertension, diabetes or hypercholesterolaemia whether physicians adhered to guidelines including generic simvastatin, metformin or glibenclamide or chose to ignore the recommendations and prescribe drugs such as single sourced atorvastatin [71]. However there was an appreciable difference in expenditure [71].

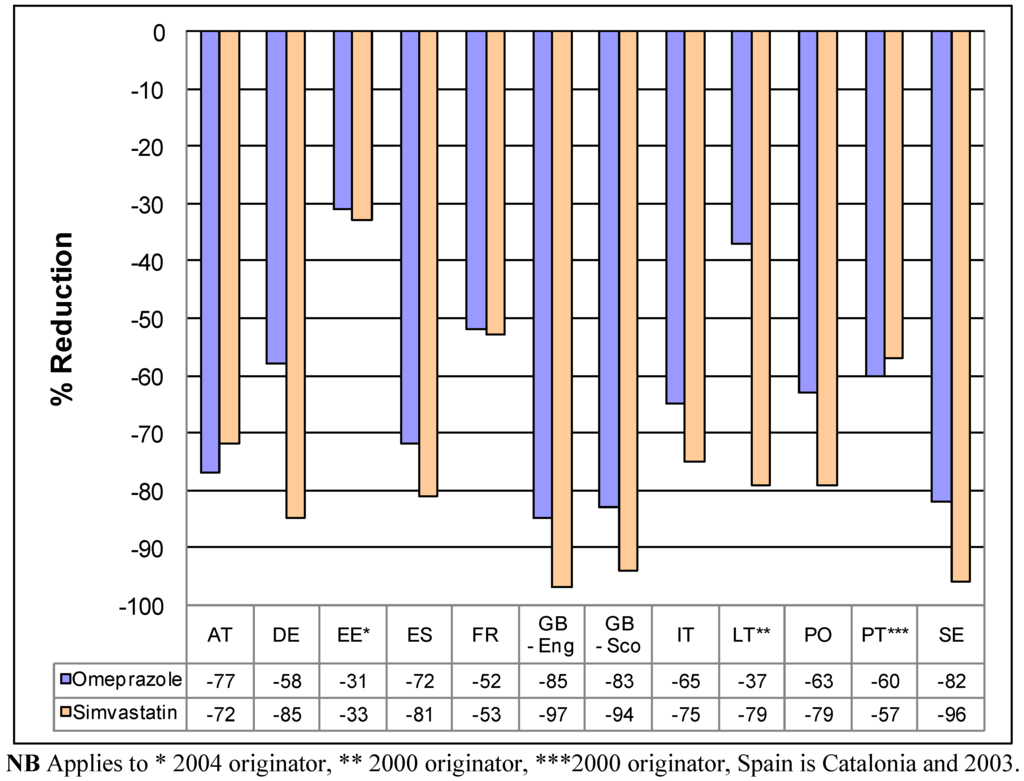

3.3. Impact of pricing policies on reimbursed prices of generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin

Figure 1 depicts the impact of the different pricing approaches on reimbursed prices/DDD of generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin in 2007 compared with originator prices principally in 2001 in selected European countries. Not every country contained in Table 1 was able to provide data; however the majority were.

There were price reductions of 16% to 20% in Serbia when reimbursed prices/DDD for generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin respectively in 2009 compared with 2004 prices. It was impossible though to compare generic prices in 2009 with originator prices in 2004 as neither originator was reimbursed in 2004.

The patents for omeprazole and simvastatin in Italy expired in 2007. Already though in 2008, expenditure for simvastatin fell by 31% despite utilisation increasing by 17% and expenditure for omeprazole fell by 24% despite utilisation increasing by 22% [72].

Figure 1.

Percentage reduction in reimbursed expenditure for generic omeprazole and generic simvastatin in 2007 vs. 2001originator prices (unless stated) in exemplar countries.

Table 2 contains details of the overall impact of generic policies on utilisation and reimbursed expenditure in these two target disease areas.

Studies undertaken in the UK have demonstrated that patients can be successfully switched from atorvastatin to generic simvastatin without compromising care [73,74] whilst saving an estimated £2B over five years [75]. Substantial savings were also demonstrated in the Netherlands with active switching from atorvastatin to generic simvastatin [76].

Table 2.

Impact of the various measures on the utilisation and expenditure of PPIs and statins in exemplar countries in 2007 vs. 2001 unless stated.

| Country | Change in utilisation 2007 vs. 2001 | Change in expenditure 2007 vs. 2001 | Additional comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria—PPIs | 3.6 fold increase | 2.1 fold increase | Helped by voluntary price reductions for single sourced PPIs |

| Austria—statins | Approximately 2.4 fold increase | 3% decrease | Helped by prescribing restrictions for both atorvastatin and rosuvastatin |

| England—PPIs | 2.3 fold increase | 38% reduction | Helped by the introduction of the new pricing system as well a variety of measures to enhance the prescribing of generic omeprazole vs. other PPIs |

| England—statins | 5.1 fold increase | 20% increase | Helped by the introduction of the new pricing system as well a variety of measures to enhance the prescribing of low cost statins vs. single source statins |

| France—PPIs | 2.1 fold increase | 39% increase | Helped by initiatives to enhance the prescribing and dispensing of generics vs. originators |

| France—statins | 72% increase | 19% increase | Helped by initiatives to enhance the prescribing and dispensing of generics vs. originators |

| Germany—PPIs | 3.2 fold increase | 1.4 fold increase | Helped by the introduction of reference pricing for PPIs in 2003 |

| Germany—statins | 2.1 fold increase | 54% reduction | Helped by the introduction of reference pricing for statins in 2003 and the removal of atorvastatin from the normal reimbursed list |

| Lithuania—PPIs | 32.2 fold increase | 14.7 fold increase | 2007 vs. 2000 |

| Lithuania—statins | 6.1 fold increase | 1.9 fold increase | 2007 vs. 2000 |

| Poland—PPIs | Near doubling of the rate of increase in utilisation vs. expenditure | Helped by reference pricing for the PPIs | |

| Poland—statins | 4.5 fold difference in the rate of increase in utilisation vs. expenditure | Helped by reference pricing for the statins | |

| Portugal—PPIs | 3.8 fold increase | 2.3 fold increase | 2007 vs. 2000 |

| Portugal—statins | 5.3 fold increase | 2.9 fold increase | 2007 vs. 2000 |

| Scotland—PPIs | 2.3 fold increase | 52% reduction | As England |

| Scotland—statins | 4.9 fold increase | 16% increase | As England |

| Spain (Catalonia) —PPIs | 1.9 fold increase | 7.6% decrease | 2007 vs. 2003 |

| Spain (Catalonia)—statins | 86% increase | 4% decrease | 2007 vs. 2003 |

| Sweden—PPIs | 53% increase | 49% reduction | 2007 vs. 2000 |

| Sweden—statins | 3.2 fold increase | 39% reduction | 2007 vs. 2000 |

3.3. Reference pricing in a class

In addition to ongoing measures regarding generics and originators, just under half of the selected European countries have instigated reference pricing for products in a class (Table 3) especially where limited demand side measures to enhance the prescribing of generics [77]. This is different from reference pricing for originators and generics such as originator and generic omeprazole, i.e. reference pricing based on the molecule, as this applies to a class based either on pharmacological activity (ATC Level 4), such as all PPIs, all statins or all Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEIs), or all products within a therapeutic category (ATC Level 3). Examples of the latter include all atypical antispychotics to treat schizophrenia [53] or all drugs to treat hypertension. There is also voluntary reference pricing in Austria with the potential for prescribing restrictions if manufacturers are reluctant to lower their prices once generics are available in the class [6]. Details of the various schemes are included in Table A5.

Table 3.

Reference pricing in classes in exemplar countries.

| Country | Reference pricing in a class (pharmacologic or therapeutic) | Voluntary reference pricing |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | √ | |

| Germany | √ | |

| Italy | √ | |

| Poland | √ | |

| Serbia | Selected products in a class | |

| Sweden | PPIs only—still being debated in the courts. Restrictions and delistings in recent therapeutic area reviews as more complex disease areas | |

| Turkey | √ | |

| UK | Proposed by the Office of Fair Trading but rejected by the Department of Health |

This does not include external reference pricing especially for new products. Most European countries reference a number of other European countries when appraising potential reimbursed prices for new products. Prices are typically revised down if conditions change in the reference countries. This also does not include compulsory price cuts or any price: volume arrangements [78], which are in addition.

Reference pricing has also been introduced in other countries and regions outside of Europe. In 1997, reference pricing for ACEIs was introduced in British Columbia in Canada for patients aged 65 or older [13,14]. Patients have to cover the additional costs themselves for a more expensive product, which is similar to European countries. The reference price group contained three ACEIs, namely captopril, quinapril and ramipril. The other available ACEIs, benazepril, cilazapril, enalapril, fosinopril, and lisinopril, were subject to an additional co-payment of between CAN$2 to CAN$62 per month [13,14].

Evaluation of the scheme demonstrated that outcomes were not compromised in patients who were switched ACEIs. In addition, healthcare utilisation and associated costs outside of drug costs did not change following the reform, and patients did not discontinue their treatment as a result of the reform [13]. Drug cost savings were estimated at CAN$5.8 million the first year of introduction, some 6% of all cardiovascular drug expenditure among senior citizens in British Columbia [14].

3.4. Strategies to address concerns with generics when these occur

Health authorities and health insurance agencies have instigated a number of initiatives to address patient and physician concerns with the effectiveness and safety of generics when prescribing and dispensing them, including substitution, where these occur (Table 4) [1,2,3,4,6,7,11,25,27,43,79]. There have also been strategies in some European countries to reduce potential patient confusion when prescribed multiple branded generics.

Table 4.

Health Authority and Health Insurance approaches to address patient and physician concerns with generics including potential duplication.

| Key Stakeholder Groups | Activities |

|---|---|

| Physicians |

|

| Pharmacists |

|

| Patients |

|

Products currently excluded for substitution in Sweden include a number of anti-epileptic drugs, ciclosporin and warfarin. In Spain, non-substitutable products include carbamazapine, ciclosporin, digoxin, phenytoin, and vigabatrin. In the UK, the British National Formulary (BNF) as well as the National Prescribing Centre, have suggested that several drugs should only be prescribed by their brand name rather than by INN to enhance subsequent care as bioequivalence cannot be assumed. In addition, care with certain other products and preparations [25,64,65,80] is required including lithium, various opiods and carbamazepine.

4. Discussion

We believe a number of conclusions can be drawn from these findings, as well as provide guidance for the future. These include the fact that the various pricing policies for generics (Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4) have resulted in appreciable decreases in the prices of generic omeprazole and simvastatin vs. originator prices pre patent loss or 2000/2001 (Figure 1) in the selected European countries. As a result, releasing considerable resources to help fund increased utilisation of PPIs and statins. Sometimes, this has been at reduced overall expenditure (Table 2). Alongside this, there have also been more general savings from the availability of generics, which can be considerable, e.g. France, Sweden and the UK [4,11,27,64,67]. These savings appear to be achieved without compromising care [22,46,52,53,71]. As a result, endorsing the instigation of the various supply and demand side initiatives surrounding generics as a necessary cost containment tool to address growing budgetary pressures.

Care though is needed in a minority of situations for health authorities and health insurance agencies to fully realise the resource benefits from the availability of generics. This includes for instance limiting or discouraging substitution for different formulations of lithium, ciclosporin, and opiods as well as certain products for the management of epilepsy. It also includes instigating prescribing databases in pharmacies, or other alternative measures, to reduce the possibility of duplication when patients are dispensed different branded generics each with different names.

We acknowledge that we have not discussed biosimilars. This is in view of the appreciable difference in effectiveness and safety data requirements for registration between oral generic small molecules and biosimilars, as well as the need for post marketing pharmacovigilance studies with biosimilars. This topic will though be discussed in future articles as biosimilars are becoming increasingly important with the biopharmaceutical market expected to grow by some 12 to 15% per year over the next few years [33,81].

As stated, further reforms are essential to ensure continued and comprehensive healthcare in Europe. Consequently, pharmaceutical companies need to appreciate and plan for significant price decreases once drugs lose their patent. This will increasingly become a pre-requisite to fund new premium priced innovative drugs. Otherwise, future patient care and commercial goals will be compromised. Likewise, physicians also need to fully appreciate the rationale behind ongoing reforms surrounding the availability of generics and work with them to fund increased volumes and new drugs within available resources.

Alongside this, European and other countries need to learn from each other. This is already happening for health reforms in general [82]. Future initiatives in some European countries could include measures to further lower prices of multiple sourced products where pertinent as well as accelerate reimbursement of generics with more frequent reviews of reimbursed prices. Austria and Norway provide examples of aggressive prescriptive pricing policies that can be introduced especially when taking into consideration their population sizes (Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4). Sweden, the UK, and more recently Lithuania, provide examples of additional measures that could be introduced to increase transparency in the pricing of generics linked with either high INN prescribing (Lithuania and the UK) or compulsory substitution unless concerns (Sweden). High INN prescribing is in line with recommendations from the WHO and International Society of Drug Bulletins [83]. Transparency with the pricing of generics is becoming increasingly important giving the extent of rebates and discounts that have, or still exist, to enhance the dispensing of particular generics [4,16,27,84]. As a result, demonstrate to health authorities the potential to further lower prices mindful though of the need to maintain a viable and sustainable market for generic manufacturers in Europe.

Compulsory generic substitution or INN prescribing is though not currently permitted in all European countries, and initiatives to increase the transparency for pricing generics is also not in operation across Europe. Possible approaches in these countries could include measures to lower or negate patient co-payment if particular branded generics are priced at a fixed percentage below the current reference price. This measure has been successfully applied in Germany. However, the potential impact will depend on the extent of the current co-payment per pack, and could be viewed as an alternative to more aggressive prescriptive pricing policies for generics.

Other measures to conserve valuable resources alongside pricing initiatives include policies to further enhance the prescribing of generics first line through for instance economic incentives, prescribing targets and/ or prescribing restrictions for single sourced products [4,11,12,27,75,85,86]. These measures will have a direct impact in further lowering prices where market forces are used to reduce prices post patent loss. These issues will be explored in future papers.

5. Conclusions

The availability of generics and their increasing utilisation, combined with strategies to lower their prices, has led to considerable savings across Europe. These savings enable European health authorities and health insurance companies to provide comprehensive and equitable healthcare within finite resources. Changing demographics and the continued launch of new premium price products mandate that European countries must continue to learn from each other to further enhance efficiency given the current wide variation in reimbursed prices and the wide variation in the utilisation of generics. Care though is needed in a minority of situations when prescribing or dispensing generics to ensure savings are maximised. This may mean prescribing the originator drug in a limited number of situations.

Different strategies are possible across Europe to enable European countries to further enhance efficiency in ambulatory care prescribing. However, possible additional measures will be country specific given the complexities surrounding prescribing in each country and the different circumstances

Acknowledgements

The majority of the authors are employed directly by health authorities or health insurance agencies or are advisers to these organisations. No author has any other relevant affiliation or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript, although Morten Andersen has received teaching grants from the Danish Association of Pharmaceutical Industries for providing education on pharmacoepidemiology. No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

We would like to acknowledge the help of INFARMED with providing the NHS data for Portugal, Helga Festoy (HF) from NoMA with critique details of the pricing policy for generics in Norway, and the NHS Information Centre in Leeds for the provision of the data for England.

Appendix

Table A1.

Definitions used in the paper.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Generics [1,2,22,25,46,87] |

|

| Originators | These are the brand products pre-patent loss as well as the continuing brand name after patent loss |

| Pricing approaches for generics |

|

Table A2.

Prescriptive pricing approaches for generics in selected European countries.

| Country | Pricing initiatives |

|---|---|

| France [4] |

|

| Netherlands [19,88] |

|

| Norway [43,89] |

|

| Turkey |

|

Table A3.

Market Forces approaches to the pricing of generics in selected European countries.

| Country | Pricing initiatives |

|---|---|

| Germany [26,90] |

|

| Poland [2] |

|

| Spain [12,63,91] |

|

| Sweden [5,11] |

|

| UK [24,25,26,27,29,64,65,66,68,84] |

|

Table A4.

Mixed approaches to the pricing of generics in exemplar European countries.

| Country | Pricing initiatives |

|---|---|

| Austria [6,86,92] |

|

| Estonia |

|

| Italy [93,94] |

|

| Lithuania |

|

| Portugal [1,3] |

|

| Serbia |

|

Table A5.

Countries with reference pricing for the class among the selected European countries and the impact where known.

| Country | Reference pricing initiatives and impact |

|---|---|

| Austria [6,86] |

|

| Germany [28,29] | Formula use for reference pricing in a class (e.g. PPIs and statins):

|

| Italy [29,95] |

|

| Poland [2,53] |

|

| Serbia |

|

| Sweden [5,11,29,96] |

|

| Turkey |

|

| UK (25,27,29,67,97,98) |

|

References

- Simoens, S. The Portuguese generic medicines market: A policy analysis. Pharm. Pract. 2009, 7, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Simoens, S. Developing competitive and sustainable Polish generic medicines market. Croat. Med. J. 2008, 50, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Teixeira, I.; Vieira, I. Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information Portugal; Vogler, S., Morak, S., Eds.; Gesundheit Österreich GmbH, Geschäftsbereich Österreichisches Bundesinstitut für Gesund-heitswesen / Austrian Health Institute (GÖG/ÖBIG): Vienna, Austria, 2008. Available online: http://ppri.oebig.at/Downloads/Results/Portugal_PPRI_2008.pdf/ (accessed on 2 March 2010).

- Sermet, C.; Andrieu, V.; Godman, B.; Van Ganse, E.; Haycox, A.; Reynier, J.P. Ongoing pharmaceutical reforms in France; considerations for other countries and implications for key stakeholder groups in France. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2010, 8, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wettermark, B.; Godman, B.; Andersson, K.; Gustafsson, L.L.; Haycox, A.; Bertele, V. Recent national and regional drug reforms in Sweden—Implications for pharmaceutical companies in Europe. Pharmacoeconomics 2008, 26, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Godman, B.; Bucsics, A.; Burkhardt, T.; Haycox, A.; Seyfried, H.; Wieninger, P. Insight into recent reforms and initiatives in Austria; implications for key stakeholders. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2008, 8, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Heikkilä, R.; Mäntyselkä, P.; Hartikainen-Herranen, K.; Ahonen, R. Customers’ and physicians’ opinions of experiences with generic substitution during the first year in Finland. Health Policy 2007, 82, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Orzella, L.; Chini, F.; Rossi, P.; Borgia, P. Physician and patient characteristics associated with prescriptions and cost of drugs in the Lazio region of Italy. Health Policy 2010, 95, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Tsiantou, V.; Zavras, D.; Kousoulakou, H.; Geitona, M.; Kyriopoulos, J. Generic medicines: Greek physicians’ perceptions and prescribing policies. J. Clin. Pharm. Therapeut. 2009, 34, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Garattini, L.; Motterlini, N.; Cornago, D. Prices and distribution margins of in-patent drugs in pharmacy: A comparison in seven European countries. Health Policy 2008, 85, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Godman, B.; Wettermark, B.; Hoffman, M.; Andersson, K.; Haycox, A.; Gustafsson, L.L. Multifaceted national and regional drug reforms and initiatives in ambulatory care in Sweden; Global relevance. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2009, 9, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Comma, A.; Zara, C.; Godman, B.; Augusti, A.; Diogene, E.; Wettermark, B.; Haycox, A. Policies to enhance the efficiency of prescribing in the Spanish Catalan Region: Impact and future direction. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2009, 9, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Schneeweiss, S.; Walker, A.; Glynn, R.; Maclure, M.; Dortmuth, C.; Soumerai, S. Outcomes of reference pricing for angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors. NEJM 2002, 346, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Schneeweiss, S.; Dortmuth, C.; Grootendorst, P.; Soumerai, S.; Maclure, M. Net Health Plan Savings From Reference Pricing for Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors in Elderly British Columbia Residents. Med. Care 2004, 42, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Cameron, A.; Ewen, M.; Ross-Degnan, D.; Ball, D.; Laing, R. Medicine prices, availability and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: A secondary analysis. Lancet 2009, 273, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Simoens, S. Generic medicine pricing in Europe: Current issues and future perspective. Jpn. Med. Econom. 2008, 11, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeley, E.; Kanavos, P. Generic medicines from a societal perspective: Savings for health care systems. Eurohealth 2008, 14, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Seeley, E. Maximising the benefits from generic competition. Euro. Observ. 2008, 10, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Simoens, S. Trends in generic prescribing and dispensing in Europe. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 1, 497–503. [Google Scholar]

- Simoens, S. International comparison of generic medicine prices. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2007, 23, 2647–2654. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiras, M.; Alves, N.; Marcelino, D.; Cortes, M.; Weinman, J.; Horne, R. Assessing lay beliefs about generic medicines: Development of the generic medicines scale. Psychol. Health Med. 2009, 14, 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Kesselheim, A.; Stedman, M.; Bubrick, E.; Gagne, J.; Misono, A.; Lee, J.; Brookhardt, A.; Avron, J.; Shrank, W. Seisure outcomes following the use of generic vs. brand-name antiepileptic drugs. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs 2010, 70, 605–621. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, G.; Hassali, M.; Shafie, A.; Awaisu, A. A survey exploring knowledge and perceptions of general practitioners towards the use of generic medicines in the northern state of Malaysia. Health Policy 2010, 95, 229–325. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission—Executive Summary of the Pharmaceutical Sector Inquiry Report. Reference EU Commission report. 8 July 2009. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/pharmaceuticals/inquiry/communication_en.pdf/ (accessed on 30 May 2010).

- Ferner, R.; Lenney, W.; Marriott, J. Controversy over generic substitution. BMJ 2010, 340, 1341–1343. [Google Scholar]

- Price falls are following a familiar pattern. Generics Bull. 2010. Available online: http://www.-wavedata.co.uk/btn/generics%20bulletin/0000-60%20Price%20falls%20are%20following-%20a%20familiar%20pattern%2028%20May%202010.pdf/ (Accessed on 24 June 2010).

- McGinn, D.; Godman, B.; Lonsdale, J.; Way, R.; Wettermark, B.; Haycox, A. Initiatives to enhance the efficiency of statin and proton pump inhibitor prescribing in the UK: Impact and implications. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2010, 10, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Godman, B.; Schwabe, U.; Selke, G.; Wettermark, B. Update of recent reforms in Germany to enhance the quality and efficiency of prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors and lipid-lowering drugs. Pharmacoeconomics 2009, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Godman, B.; Haycox, A.; Schwabe, U.; Joppi, R.; Garattini, S. Having your cake and eating it: Office of Fair Trading proposal for funding new drugs to benefit patients and innovative companies. Pharmacoeconomics 2008, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, G. The European generic pharmaceutical market in review: 2006 and beyond. Jpn. Gener. Med. 2006, 4, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiras, M.; Marcelion, D.; Cortes, M. People’s views on the level of agreement of generic medicines for different illneses. Pharm. World Sci. 2008, 30, 590–594. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, B. Indonesian doctors are told to prescribe more generic drugs to reduce escalating health costs. BMJ 2010, 340, c349. [Google Scholar]

- Simoens, S. Interchangeability of off-patent medicines: A pharmacoeconomic perspective. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2008, 8, 519–521. [Google Scholar]

- Shrank, W.; Cox, E.; Fischer, M.; Mehta, J.; Choudry, N. Patients’ perception of generic medications. Health Affair 2009, 28, 546–556. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, H.; Shrank, W. Increasing generic drug us in Medicare Part D: The role of government. JAGS 2007, 55, 1108–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Godman, B.; Wettermark, B. Impact of reforms to enhance the quality and efficiency of statin prescribing across 20 European countries. In The 9th Congress of the European Association for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Edinburgh, Scotland, 12–15 July 2009; pp. 65–69.

- Godman, B.; Wettermark, B. Trends in consumption and expenditure of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in 20 European countries. In The 9th Congress of the European Association for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Edinburgh, Scotland, 12–15 July 2009; pp. 71–75.

- Garattini, S.; Bertele, V.; Godman, B.; Haycox, A.; Wettermark, B.; Gustafsson, L.L. Enhancing the rational use of new medicines across European healthcare systems—A Position Paper. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 64, 1137–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.; Emanuel, E. Tier 4 drugs and the fraying of the social compact. NEJM 2008, 359, 333–335. [Google Scholar]

- Wettermark, B.; Persson, M.E.; Wilking, N.; Kalin, M.; Korkmaz, S.; Hjemdahl, P.; Godman, B.; Petzold, M.; Gustafsson, L.L. Forecasting drug utilization and expenditure in a metropolitan health region. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shrank, W.; Cadarette, S.; Cox, E.; Fischer, M.; Metha, J.; Brookhardt, A.; Avron, J.; Choudry, N. Is there a relationship between patient beliefs or communication about generic drugs and medication utilization? Med. Care 2009, 47, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kanavos, P. Generic policies: Rhetoric vs. reality. Euro. Observ. 2008, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kjoenniksen, I.; Lindbaek, M.; Grannas, A. Patients’ attitudes towards and experiences of generic drug substitution in Norway. Pharm. World Sci. 2006, 28, 284–289. [Google Scholar]

- Himmel, W.; Simmenroth-Nayada, A.; Niebling, W.; Ledig, T.; Jansen, R.D.; Kochen, M.M.; Gleiter, C.H.; Hummers-Pradier, E. What do primary care patients think about generic drugs? J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 43, 472–479. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney, M. Generic drugs: Protest group was not quite what it seemed. BMJ 2010, 340, c1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesselheim, A.; Misoni, A.; Lee, J.; Stedman, M.; Brookhardt, M.; Choudry, N.; Shrank, W. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease—A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2008, 300, 2514–2526. [Google Scholar]

- Mofsen, R.; Balter, J. Case reports of the reemergence of psychotic symptoms after conversion from brand-name clozapine to a generic formulation. Clin. Ther. 2001, 23, 1720–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, C.A.; Mascarenas, C.; Timmerman, I. Increasing psychosis in a patient switched from Clozaril to generic clozapine. Am. J. Psychiat. 2006, 163, 746. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, D.J.; Taylor, S.; Goldman, M.; Barry, K.; Blow, F.; Milner, K.K. Clinical equivalence of generic clozapine. Community Ment. HealthJ. 2005, 41, 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Alessi-Severini, S.; Honcharik, P.L.; Simpson, K.D.; Eleff, M.K.; Collins, D.M. Evaluation of an interchangeability switch in patients treated with clozapine: A retrospective review. J. Clin. Psychiat. 2006, 67, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Paton, C. Generic clozapine: Outcomes after switching. Br. J. Psychiat. 2006, 89, 184–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bazire, S.; Burton, V. Generic clozapine in schizophrenia: What is all the fuss about? Pharm. J. 2004, 173, 720–721. [Google Scholar]

- Araszkiewicz, A.A.; Szabert, K.; Godman, B.; Wladysiuk, M.; Barbui, C.; Haycox, A. Generic olanzapine: Health authority opportunity or nightmare? Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2008, 8, 549–555. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, A. Balancing Big Pharma’s books. BMJ 2008, 336, 418–419. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, H.; Austvoll-Dahlgren, A.; Aaserud, M.; Oxman, A.D.; Ramsay, C.; Vernby, Å.; Kösters, J.P. Pharmaceutical policies: Effects of financial incentives for prescribers (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 3. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Guidelines for ATC Classification and DDD Assignment 2009; WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology: Oslo, Norway, 2009. Available online: www.whocc.no/ (accessed on 15 January 2010).

- Studies in Drug Utilization—Methods and Applications; Bergman, U.; Gimsson, A.; Wahba, A.; Westerholm, B. (Eds.) World Health Organization Regional Publications: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1979.

- World Health Organisation (WHO). The Selection of Essential Drugs; Technical Report Series No. 615; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Introduction to Drug Utilisation Research; WHO International Working Group for Drug Statistics Methodology, WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Utilization Research and Clinical Pharmacological Services: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. Available online: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/ quality_safety/ safety_ efficacy/ Drug%20utilization%20research.pdf/ (accessed on 30 January 2010).

- Walley, T.; Folino-Gallo, P.; Schwabe, U.; Van Ganse, E. Variations and increase in use of statins across Europe: Data from administrative databases. BMJ 2004, 328, 385–386. [Google Scholar]

- Vlahović-Palcevski, V.; Gantumur, M.; Radoševic, N.; Palčevski, C.; Vander Stichele, R. Coping with changes in the Defined Daily Dose in a longitudinal drug consumption database. Pharm. World Sci. 2010, 32, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Walley, T.; Folino-Gallo, P.; Stephens, P.; Van Ganse, E. Trends in prescribing and utilisation of statins and other lipid lowering drugs across Europe 1997–2003. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 60, 543–551. [Google Scholar]

- Germed. Una Peticion Historica. 7 December 2009. Available online: http://www.germed.es/71220092.htm/ (accessed on 10 June 2010).

- Chaplin, S.; Duerden, M. When Brands Are Best—Brand vs. Generic Prescribing; Wiley Interface Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Duerden, M. Making sense of drug pricing. In Prescriber Supplement; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2006; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Fair Trading (UK). The Pharmaceutical Price Regulation System: An OFT Study. Annexe A: Market for Prescription Pharmaceuticals in the NHS; The Office of Fair Trading: London, UK, 2007. Available online: http://www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/reports/comp_policy/oft885a.pdf/ (Accessed Mar 3 2010).

- Coombes, R. GPs saved £400m in 2008 by increasing use of generic drugs. BMJ 2009, 338, 1230. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D.; Ferner, R. New drugs for old: disinvestment and NICE. BMJ 2010, 340, 690–692. [Google Scholar]

- Consultez l'accord national sur les génériques et ses avenants. Available online: http://www.ameli.fr/professionnels-de-sante/pharmaciens/votre-convention/textes/accord-national-sur-les-generiques/index.php (Accessed 28 June 2010).

- Médicaments génériques: plus d’1 milliard d’euros d’économie en 2009. Available online: http://www.ameli.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/documents/CP_generiques_nov_09_vdef.pdf/ (Accessed 28 June 2010).

- Norman, C.; Zarrinkoub, R.; Hasselström, J.; Godman, B.; Granath, F.; Wettermark, B. Potential savings without compromising the quality of care. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2009, 63, 1320–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Osmed Database Reports 2007 and 2008. Available online: http://www.agenziafarmaco.it/it/content/rapporti-osmed-luso-dei-farmaci-italia/ (Accessed 24 May 2010).

- Usher-Smith, J.A.; Ramsbottom, T.; Pearmain, H.; Kirby, M. Evaluation of the cost savings and clinical outcomes of switching patients from atorvastatin to simvastatin and losartan to candersartan in a Primary care setting. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007, 61, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Usher-Smith, J.; Ramsbottom, T.; Pearmain, H.; Kirby, M. Evaluation of the clinical outcomes of switching patients from atorvastatin to simvastatin and losartan to candesartan in a primary care setting: 2 years on. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2008, 62, 480–484. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.; Bogle, R. Switching statins - Using generic simvastatin as first line could save £2bn over five years in England. BMJ 2006, 332, 1344–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Gumbs, P.; Verschuren, W.; Souverein, P.; Mantel-Tuwisse, A.; de Wit, A.; de Boer, A.; Klungel, K. Society already achieves economic benefits from generic substitution but fails to do the same for therapeutic substitution. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 64, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wettermark, B.; Godman, B.; Jacobsson, B.; Haaijer-Ruskamp, F. Soft regulations in pharmaceutical policymaking - an overview of current approaches and their consequences. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2009, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Adamski, J.; Godman, B.; Ofierska-Sujkowska, G.; Osinska, B.; Herholz, H.; Wendykowska, K.; Laius, O.; Jan, S.; Sermet, C.; Zara, C.; Kalaba, M.; Gustafsson, R.; Garuolienè, K.; Haycox, A.; Garattini, S.; Gustafsson, L.L. Review of risk sharing schemes for pharmaceuticals: considerations, critical evaluation and recommendations for European payers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Versantvoort, C.; Maliepaard, M.; Lekkerkerker, F. Generics: what is the role of authorities. Neth. J. Med. 2008, 66, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- British National Formulary. Available online: http://bnf.org/bnf/index.htm/ (Accessed 3 March 2010).

- Simoens, S. Health economics of market access for biopharmaceuticals and biosimilars. J. Med. Econom. 2009, 12, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Toth, F. Healthcare policies over the last 20 years: reforms and counter-reforms. Health Policy 2010, 95, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, C.; Vandevelde, F. Use of International Nonproprietary names (INN) among members. ISDB Newsletter 2006, 20, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kanavos, P. Do generics offer significant savings to the UK National Health Service? Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2007, 23, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Wettermark, B.; Pehrsson, A.; Juhasz-Haverinen, M.; Veg, A.; Edlert, M.; Törnwall-Bergendahl, G.; Almkvist, H.; Godman, B.; Granath, F.; Bergman, U. Financial incentives linked to self-assessment of prescribing patterns – a new approach for quality improvement of drug prescribing in primary care. Qual. Primary Care 2009, 17, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Godman, B.; Burkhardt, T.; Bucsics, A.; Wettermark, B.; Wieninger, P. Impact of recent reforms in Austria on utilisation and expenditure of PPIs and lipid lowering drugs; implications for the future. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2009, 9, 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2004/27/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31st March 2004 amending Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use. Official J. Eu. 2006, L 136, 34–57.

- Puig-Junoy, J. Politicas de fomento de la competencia en precios en el mercado de genericos: leccines de la experiencia europea. Gac. Sanit. 2010, 24, 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Festoy, H.; Sveen, K.; Yu, L.-M.; Gjonnes, L.; Gregersen, T. Norway – Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information. October 2008. Available online: http://ppri.oebig.at/Downloads/Results/Norway_PPRI_2008.pdf/ (Accessed 3 June 2010).

- Schreyögg, J.; Henke, K.-D.; Busse, R. Managing Pharmaceutical Regulation in Germany. Discussion Paper; Technische Universität Berlin, Fakultät Wirtschaft und Management: Berlin, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Antoňanzas, F.; Oliba, J.; Pinillos, M.; Juàrez, C. Economic aspects of the new Spanish laws on pharmaceutical preparations. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2007, 8, 297–300. [Google Scholar]

- Godman, B.; Bucsics, A.; Burkhardt, T.; Schmitzer, M.; Wettermark, B.; Wieninger, P. Initiatives to enhance renin-angiotensin prescribing efficiency in Austria: impact and implications for other countries. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2010, 10, 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Garattini, L.; Ghislandi, S. Off-patent drugs in Italy: a short sighted view? Eur. J. Health Econ. 2006, 7, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ghislandi, S.; Krulichova, I.; Garattini, L. Pharmaceutical policy in Italy: towards a structural change? Health Policy 2005, 72, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rocchi, F.; Addis, A.; Martini, N. Current national initiatives about drug policies and cost control in Europe: the Italy example. J. Ambulatory Care Manage. 2004, 27, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wessling, A.; Lundin, D. The Review of Drugs against Disease Caused by Acid Stomach – a Summary; Pharmaceuticals Benefits Board: Solna, Sweeden, 2006. Available online: http://www.tlv.se/Upload/Genomgangen/summary-stomach-acid.pdf/ (Accessed 5 May 2010).

- Taylor, L. New UK PPRS includes 3.9% price cut, flexible pricing and generic substitution. 20 November 2008. Available online: http://www.eatg.org/eatg/Global-HIV-News/Access-to-treatment/New-UK-PPRS-includes-3.9-price-cut-flexible-pricing-and-generic-substitution/ (Accessed 3 May 2010).

- Anonymous. Better Care Better Value Indicator. Low cost PPI prescribing. Available online: http://www.productivity.nhs.uk/Def_IncreasingLowCostPPIPrescribing.aspx/ (Accessed 3 May 2010).

© 2010 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).