Results of an Exploratory Crossover Pharmacokinetic Study Evaluating a Natural Hemp Extract-Based Cosmetic Product: Comparison of Topical and Oral Routes of Administration †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. General Characteristics of Participants

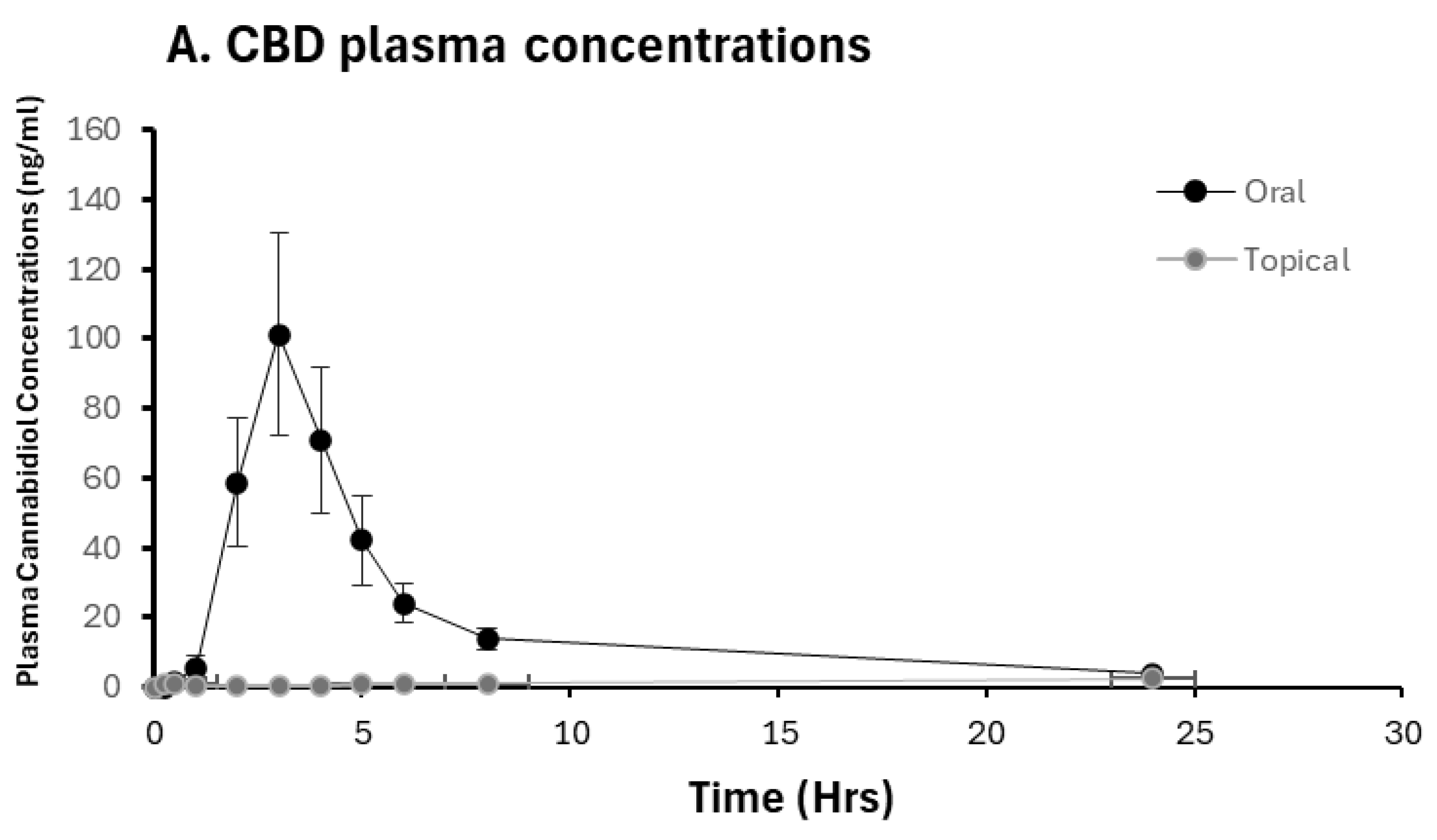

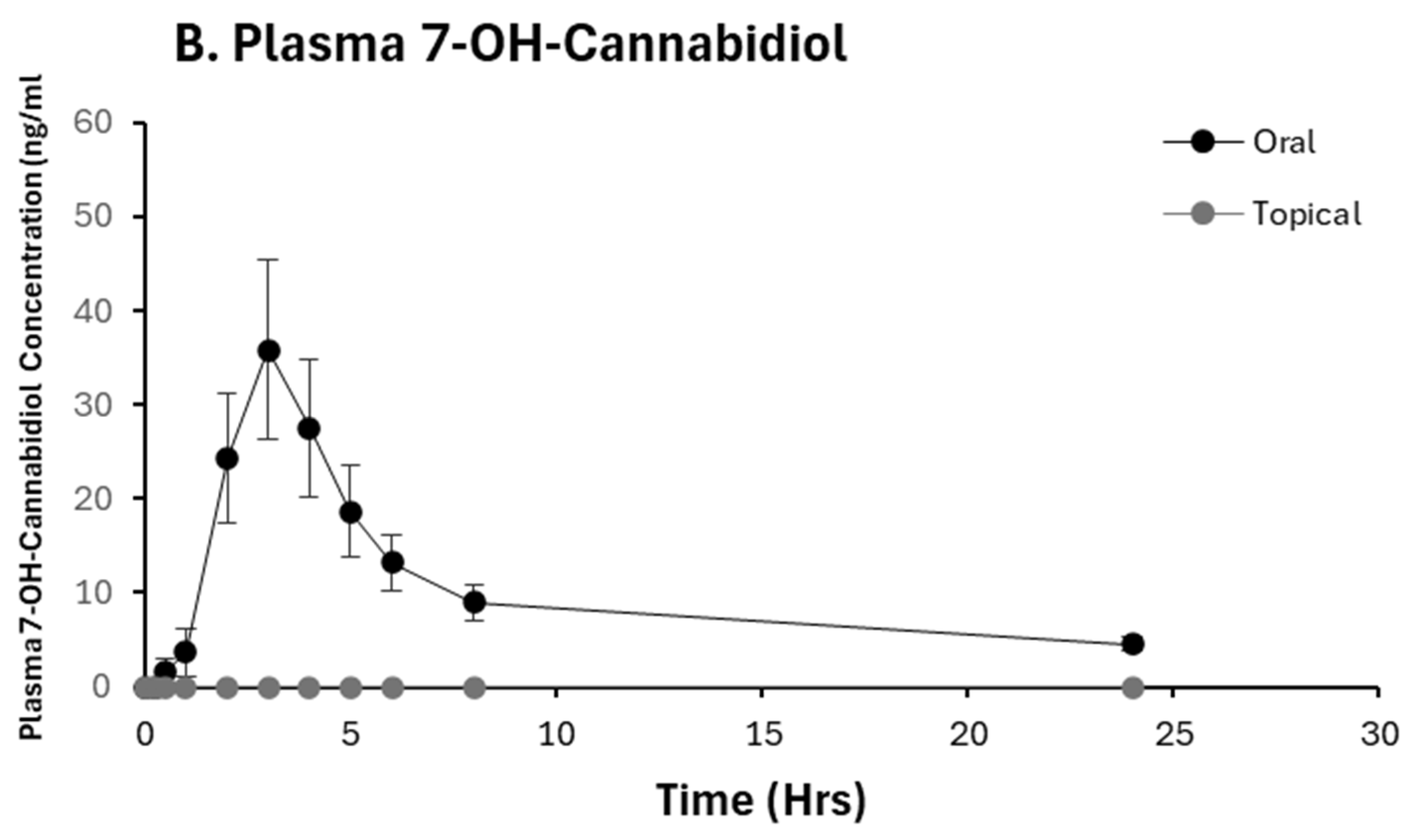

2.2. Pharmacokinetic Analysis of CBD and 7-OH-CBD

2.3. CBD Bioavailability

2.4. Adverse Events

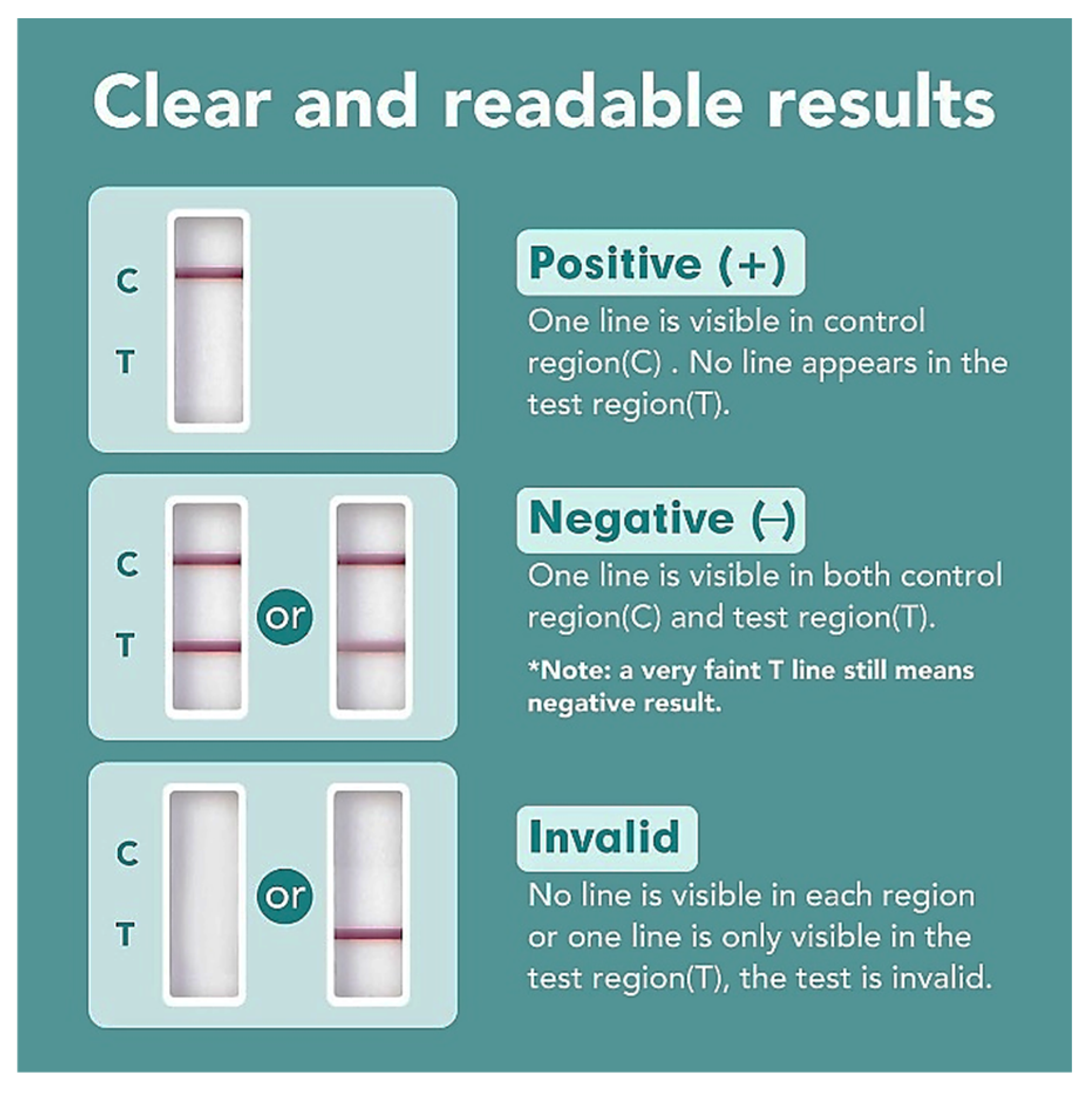

2.5. Urine Sample THC Testing

2.6. THC Test Strip Cross-Reactivity with CBD and Its Metabolites

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Product

4.2. Participants and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

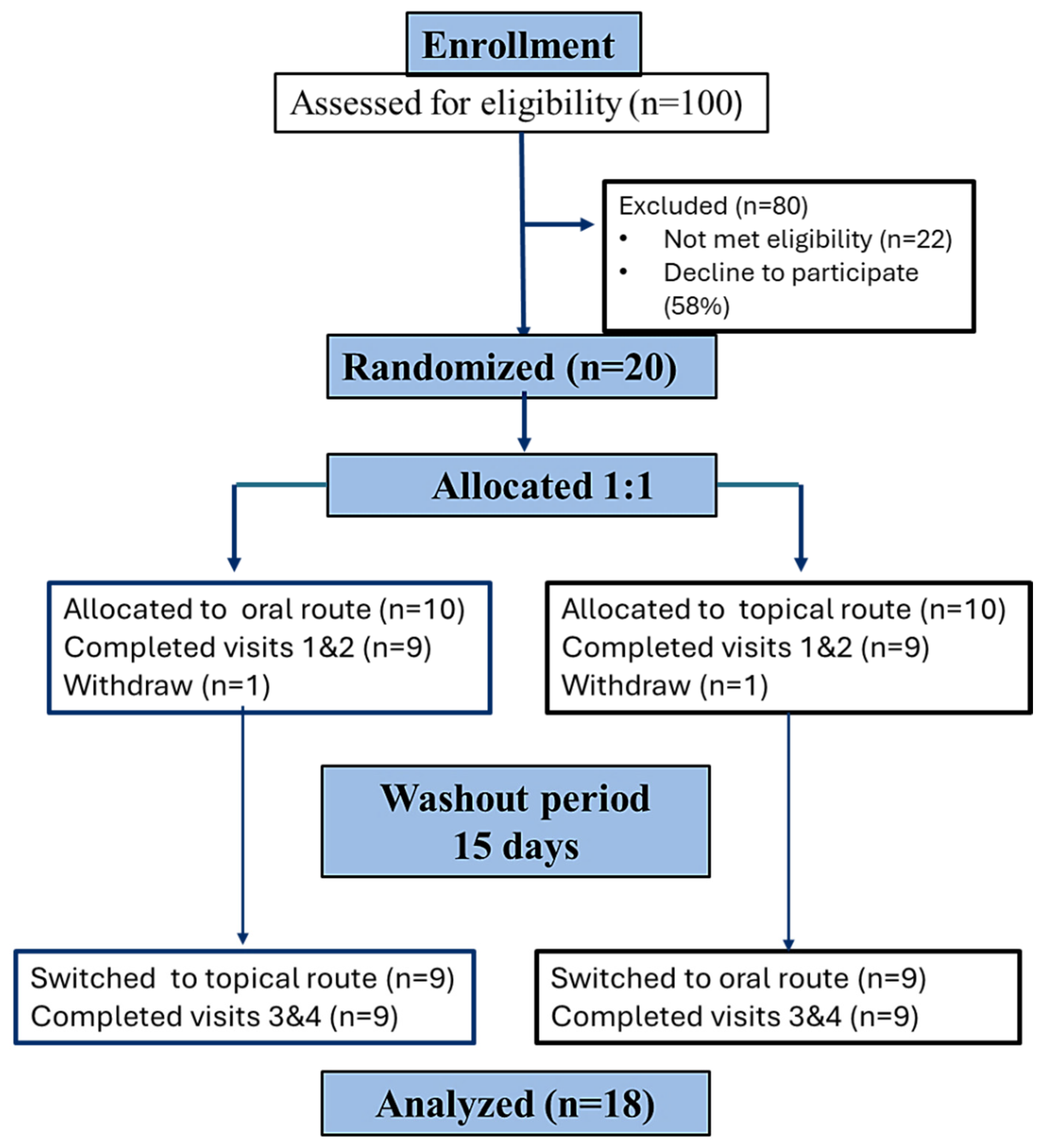

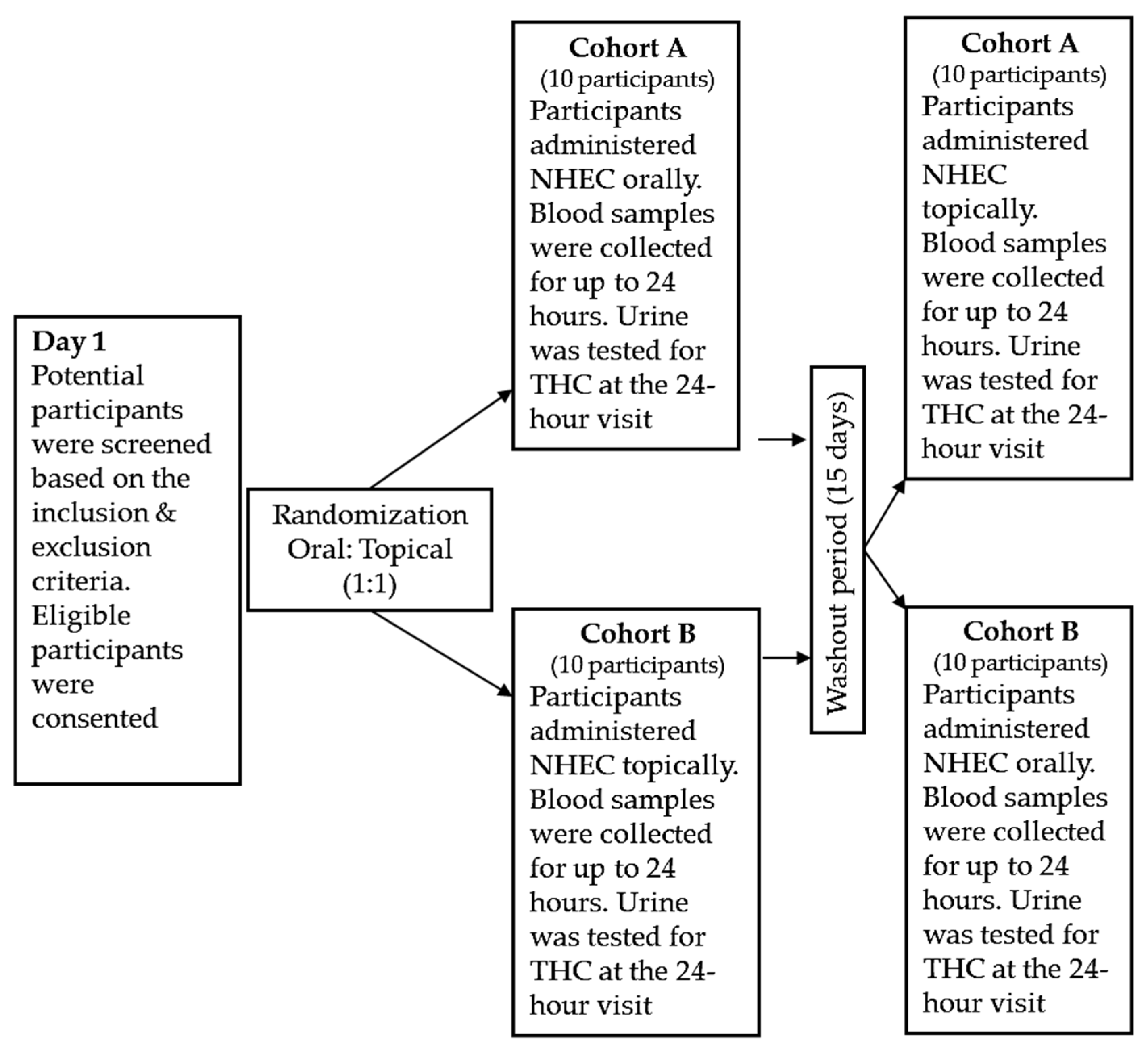

4.3. Study Design

4.4. Sample Size Rationale

4.5. Study Outcomes

4.6. Plasma Analysis for CDB, THC, and Their Metabolites

4.7. Pharmacokinetic Analysis

4.8. In Vitro Analysis of Cross-Reactivity of Cannabinoid Urine Test Strips with CBD and Its Metabolites

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MCT | medium-chain triglyceride |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CTSI | Center for Clinical & Translational Science |

| CBC | Complete Blood Count |

| LC-MS/MS | liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| COOH-THC | carboxy delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol |

| NHEC | natural hemp extract-based cosmetic |

| CBD | cannabidiol |

| THC | tetrahydrocannabinol |

| 7-OH-CBD | 7-hydroxy cannabidiol |

| Δ9-THC | delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol |

| Δ8-THC | delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol |

| 11-OH-THC | delta-11 tetrahydrocannabinol |

| CBN | cannabinol |

| Cmax | maximum plasma concentration |

| Tmax | maximum plasma concentration |

| AUC0–24 | area under the plasma concentration-time curve from zero to last measured concentration |

| AUC0-inf | AUC from time zero to infinity |

| T1/2 | terminal (elimination) half-life |

| CL/F | apparent clearance |

References

- Farinon, B.; Molinari, R.; Costantini, L.; Merendino, N. The seed of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.): Nutritional Quality and Potential Functionality for Human Health and Nutrition. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Responds to Three GRAS Notices for Hemp Seed-Derived Ingredients for Use in Human Food. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/hfp-constituent-updates/fda-responds-three-gras-notices-hemp-seed-derived-ingredients-use-human-food#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Food%20and%20Drug,different%20hemp%20seed%2Dderived%20ingredients (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- VanDolah, H.J.; Bauer, B.A.; Mauck, K.F. Clinicians’ Guide to Cannabidiol and Hemp Oils. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 1840–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Government Information. Agricultural Act of 2014. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-113hr2642enr/pdf/BILLS-113hr2642enr.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Conaway, M. Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ334/PLAW-115publ334.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Blessing, E.M.; Steenkamp, M.M.; Manzanares, J.; Marmar, C.R. Cannabidiol as a Potential Treatment for Anxiety Disorders. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, J.Y.; Wang, P.Y.; Peng, Y.C. Therapeutic potential of cannabidiol (CBD) in anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 339, 116049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, V.; Reddy, D.S. Cannabidiol Therapy for Refractory Epilepsy and Seizure Disorders. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1264, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, E.H.; Lee, J.H. Cannabinoids and Their Receptors in Skin Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzumi, A.; Yoshizaki-Ogawa, A.; Fukasawa, T.; Sato, S.; Yoshizaki, A. The Potential Role of Cannabidiol in Cosmetic Dermatology: A Literature Review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2024, 25, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiginton, K. Will CBD Cause Me to Fail a Drug Test? Available online: https://www.webmd.com/cannabinoids/features/cbd-drug-tests (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Noe, D.A. Parameter Estimation and Reporting in Noncompartmental Analysis of Clinical Pharmacokinetic Data. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2020, 9, S5–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, A.; Lindgren, J.E.; Andersson, S.; Agurell, S.; Gillespie, H.; Hollister, L.E. Single-dose kinetics of deuterium-labelled cannabidiol in man after smoking and intravenous administration. Biomed. Environ. Mass Spectrom. 1986, 13, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malave, B.; Vrooman, B. Vasovagal Reactions during Interventional Pain Management Procedures: A Review of Pathophysiology, Incidence, Risk Factors, Prevention, and Management. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, S.A.; Stone, N.L.; Yates, A.S.; O’Sullivan, S.E. A Systematic Review on the Pharmacokinetics of Cannabidiol in Humans. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiume, M.M.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; Snyder, P.W.; et al. Amended Safety Assessment of Triglycerides as Used in Cosmetics; Cosmetic Ingredient Review: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.cir-safety.org/sites/default/files/trygly122017FAR.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Watanabe, S.; Tsujino, S. Applications of Medium-Chain Triglycerides in Foods. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 802805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Kraft, K.; Rusch, L.; Fein, M.; Leone-Bay, A. Improved Bioavailability with Dry Powder Cannabidiol Inhalation: A Phase 1 Clinical Study. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110, 3946–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.; Gidal, B.; Blakey, G.; Tayo, B.; Morrison, G. A Phase I, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Single Ascending Dose, Multiple Dose, and Food Effect Trial of the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of Highly Purified Cannabidiol in Healthy Subjects. CNS Drugs 2018, 32, 1053–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadi, G.; Zhu, Z.; Crowley, H.D.; Moulin, M.; Dey, R.; Lewis, E.D.; Evans, M. Examining the Systemic Bioavailability of Cannabidiol and Tetrahydrocannabinol from a Novel Transdermal Delivery System in Healthy Adults: A Single-Arm, Open-Label, Exploratory Study. Adv. Ther. 2023, 40, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolli, A.R.; Hoeng, J. Cannabidiol Bioavailability Is Nonmonotonic with a Long Terminal Elimination Half-Life: A Pharmacokinetic Modeling-Based Analysis. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2025, 10, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perucca, E.; Bialer, M. Critical Aspects Affecting Cannabidiol Oral Bioavailability and Metabolic Elimination, and Related Clinical Implications. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crockett, J.; Critchley, D.; Tayo, B.; Berwaerts, J.; Morrison, G. A phase 1, randomized, pharmacokinetic trial of the effect of different meal compositions, whole milk, and alcohol on cannabidiol exposure and safety in healthy subjects. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saals, B.A.D.F.; De Bie, T.H.; Osmanoglou, E.; van de Laar, T.; Tuin, A.W.; van Orten-Luiten, A.C.B.; Witkamp, R.F. A high-fat meal significantly impacts the bioavailability and biphasic absorption of cannabidiol (CBD) from a CBD-rich extract in men and women. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, A.K.; Karanam, A.; Marino, S.E.; Barkley, C.M.; Remmel, R.P.; Roslawski, M.; Gramling-Aden, M.; Leppik, I.E. Food effect on pharmacokinetics of cannabidiol oral capsules in adult patients with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia 2019, 60, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, R.D.; Akanji, T.; Li, H.; Shen, J.; Allababidi, S.; Seeram, N.P.; Bertin, M.J.; Ma, H. Evaluations of Skin Permeability of Cannabidiol and Its Topical Formulations by Skin Membrane-Based Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay and Franz Cell Diffusion Assay. Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2022, 5, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchcomb, A.L.; Valiveti, S.; Hammell, D.C.; Ramsey, D.R. Human skin permeation of Delta8-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and cannabinol. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2004, 56, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junaid, M.S.A.; Tijani, A.O.; Puri, A.; Banga, A.K. In vitro percutaneous absorption studies of cannabidiol using human skin: Exploring the effect of drug concentration, chemical enhancers, and essential oils. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 616, 121540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golombek, P.; Müller, M.; Barthlott, I.; Sproll, C.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Conversion of Cannabidiol (CBD) into Psychotropic Cannabinoids Including Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): A Controversy in the Scientific Literature. Toxics 2020, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimori, S. Gastric acid level of humans must decrease in the future. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 6706–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). M13A Bioequivalencefor Immediate-Release Solid Oral Dosage Forms Questions and Answers Guidance for Industry. 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/183189/download (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Statistical Approaches to Establishing Bioequivalence. 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/70958/download (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on the Investigation of Bioequivalence. 2010. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-investigation-bioequivalence-rev1_en.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Anderson, D.J.; Freeman, T.S.; Caldwell, K.S.; Hoggard, L.R.; Reilly, C.A.; Rower, J.E. Analysis of seven selected cannabinoids in human plasma highlighting matrix and solution stability assessments. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2025, bkaf087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity/race | |

| Non-Hispanic, White | 13 (72.2%) |

| Hispanic, White | 1 (5.6%) |

| Non-Hispanic, Black | 2 (11.1%) |

| Asian | 2 (11.1%) |

| Gender | |

| Females | 13 (72.2%) |

| Age, mean ± SD | 29.8 ± 6.6 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 24.3 ± 3.2 |

| Pharmacokinetic Parameter | CBD | 7-OH-CBD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Topical | Oral | Topical | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 52.13 (3.31–820.30) | NC $ | 22.06 (2.17–224.27) | NC $ |

| Tmax (h) | 3.00 (2.00–8.00) | 24.00 (0.25–24.37) | 3.00 (2.00–24.00) | NC $ |

| T1/2 * (h) | 7.9 (3.93–29.70) | NC $ | 13.17 (6.24 -72.73) | NC $ |

| AUC0–24/(h·ng/mL) | 281 (35.45–2226.58) | 19 (2.42–149.14) | 166.77 (26.72–1040.96) | NC $ |

| AUC0–inf/(h·ng/mL) | 342.30 (225.64–510.27) | NC $ | 275.65 (51.60–1472.57) | NC $ |

| Cl/F (L/h) | 0.57 (0.09–3.52) | NC $ | 0.72 (0.13–3.84) | NC $ |

| Visit 1, n (%) * | Visit 3, n (%) * | Total THC Positivity, n (%) * |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (5.5%) | 6 (33.3%) | 7 (38.8%) |

| Sample Collection | Time of Blood Sample Collection * | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 15 min | 30 min | 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 4 h | 5 h | 6 h | 8 h | 24 h | |

| CBD and THC tests # | X @ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Clinical lab tests & | X | X | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jain, M.; Hudson, R.; Tarrell, A.; Green, D.J.; Clifford, J.J.; Watt, K.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Rower, J.E.; Yellepeddi, V.; Enioutina, E.Y. Results of an Exploratory Crossover Pharmacokinetic Study Evaluating a Natural Hemp Extract-Based Cosmetic Product: Comparison of Topical and Oral Routes of Administration. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19020231

Jain M, Hudson R, Tarrell A, Green DJ, Clifford JJ, Watt K, Mihalopoulos N, Rower JE, Yellepeddi V, Enioutina EY. Results of an Exploratory Crossover Pharmacokinetic Study Evaluating a Natural Hemp Extract-Based Cosmetic Product: Comparison of Topical and Oral Routes of Administration. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(2):231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19020231

Chicago/Turabian StyleJain, Manav, Rachel Hudson, Ariel Tarrell, Danielle J. Green, Jeffrey J. Clifford, Kevin Watt, Nicole Mihalopoulos, Joseph E. Rower, Venkata Yellepeddi, and Elena Y. Enioutina. 2026. "Results of an Exploratory Crossover Pharmacokinetic Study Evaluating a Natural Hemp Extract-Based Cosmetic Product: Comparison of Topical and Oral Routes of Administration" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 2: 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19020231

APA StyleJain, M., Hudson, R., Tarrell, A., Green, D. J., Clifford, J. J., Watt, K., Mihalopoulos, N., Rower, J. E., Yellepeddi, V., & Enioutina, E. Y. (2026). Results of an Exploratory Crossover Pharmacokinetic Study Evaluating a Natural Hemp Extract-Based Cosmetic Product: Comparison of Topical and Oral Routes of Administration. Pharmaceuticals, 19(2), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19020231