1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) stands as a formidable global health challenge, ranking as the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [

1]. Its pathogenesis is often insidious, with a majority of patients presenting with advanced, inoperable disease, where therapeutic options have historically been limited and prognosis dismal [

2]. For decades, advanced HCC was considered a chemo-resistant malignancy, creating a pressing need for novel therapeutic strategies that could meaningfully improve patient survival.

The turn of the millennium heralded a new era in HCC management with the advent of molecularly targeted therapies. The development and subsequent approval of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, represented a paradigm shift, establishing the first systemic treatment proven to significantly improve overall survival in patients with advanced HCC and ending a long period of therapeutic stagnation [

3]. Sorafenib exerts its effects by targeting a constellation of serine-threonine and tyrosine kinases involved in tumor proliferation (Raf/MEK/ERK pathway) and angiogenesis (VEGFR, PDGFR), thereby impeding both tumor growth and its blood supply [

4].

This breakthrough cemented sorafenib’s position as a first-line standard of care, a status reaffirmed in contemporary international guidelines [

5,

6]. However, the initial optimism has been tempered by a stark clinical reality: the benefits of sorafenib are neither universal nor durable. A profound interpatient heterogeneity in treatment response is observed, with only a subset of patients deriving significant benefit, while the majority exhibit primary (innate) resistance or invariably develop acquired resistance within six months of therapy initiation [

3,

7]. This renders a significant proportion of patients susceptible to the drug’s toxicities and financial costs without any survival advantage, underscoring a critical, unresolved “black box” of sorafenib response dynamics.

This clinical enigma has fueled intensive research into the molecular drivers of sorafenib resistance. Beyond established mechanisms involving kinase rewiring and autophagy, the noncoding genome has emerged as a critical regulator of cancer pathogenesis and therapy response [

8]. Among these, long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with low protein-coding potential have been implicated as master regulators of gene expression, influencing virtually all hallmarks of cancer, including in HCC [

9].

Two lncRNAs, in particular, have garnered significant attention for their roles in HCC aggressiveness: Metastasis-Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1 (MALAT1) and Urothelial Carcinoma-Associated 1 (UCA1). Preclinical models have elucidated their oncogenic functions: MALAT1 promotes HCC cell proliferation, metastasis, and chemoresistance by modulating pathways such as miR-140 sponging and TLR4/NF-κB signaling [

10,

11], while UCA1 drives tumor growth and confers resistance to various agents by sequestering tumor-suppressive miRNAs, such as miR-216b and miR-138-5p [

12,

13]. Importantly, their clinical relevance is supported by growing evidence. For instance, Abdelsattar et al. (2025) recently demonstrated that both MALAT1 and UCA1 are highly elevated in the serum of HCC patients, showing diagnostic accuracy for distinguishing HCC from chronic HCV infection, and their high expression was strongly correlated with sorafenib resistance [

14].

Furthermore, high circulating UCA1 has been consistently correlated with aggressive tumor characteristics, including large tumor size, vascular invasion, and advanced TNM stage, and has been established as an independent prognostic factor for poor overall survival [

15]. Similarly, MALAT1 overexpression in tumor tissue has been identified as a powerful predictor of tumor recurrence after liver transplantation, particularly in patients exceeding the Milan criteria [

16]. These studies firmly position UCA1 and MALAT1 as prime candidates for biomarker development.

However, while their diagnostic and prognostic potential is becoming clear, a critical gap remains in translating these findings into a dynamic, clinically actionable framework for personalizing sorafenib therapy. The question of whether these lncRNAs can guide treatment decisions in real time, stratify patients at baseline, and provide an early, liquid biopsy-based signal of emerging resistance remains largely unexplored.

The emergence of lncRNAs as modulators of drug response represents a paradigm shift in oncology pharmacogenomics. Unlike protein-coding genes subject to post-transcriptional and post-translational regulation, lncRNAs can exert rapid, direct effects on cellular phenotypes through diverse mechanisms, including chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, post-transcriptional processing, and competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) activity [

8]. Their tissue-specific expression patterns and relative stability in circulation make them attractive candidates for liquid biopsy-based monitoring. Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing have revealed that lncRNA dysregulation is not merely a bystander effect of malignant transformation but an active driver of cancer hallmarks, including sustained proliferation, evasion of growth suppression, resistance to cell death, metabolic reprogramming, and, critically, resistance to targeted therapies [

9].

In the specific context of HCC, comprehensive profiling studies have identified dozens of aberrantly expressed lncRNAs associated with clinical outcomes. However, translation of these discoveries into clinical practice has been limited by several factors: (1) lack of prospective validation in well-defined therapeutic cohorts, (2) absence of standardized quantification methods suitable for clinical laboratories, and (3) insufficient evidence linking baseline expression to dynamic treatment response trajectories. Early diagnostic studies established that elevated circulating MALAT1 and UCA1 can distinguish HCC from cirrhosis with high accuracy (AUC > 0.90) [

14,

15], but their theragnostic potential—simultaneously predicting treatment benefit and guiding therapy selection—remained unexplored. The critical question is not merely whether these lncRNAs are elevated in HCC, but whether their levels before treatment initiation can identify patients destined to fail sorafenib, and whether changes during therapy provide early signals of emerging resistance, enabling timely therapeutic intervention.

Therefore, this prospective study was designed to comprehensively evaluate the theragnostic value of MALAT1 and UCA1 in a well-defined cohort of sorafenib-treated HCC patients. We hypothesize that a combined approach, utilizing baseline expression for prognostic stratification and serial monitoring for dynamic response assessment, can unlock the full potential of these lncRNAs to optimize treatment personalization, ultimately steering patients toward more effective therapeutic strategies and improving clinical outcomes.

3. Discussion

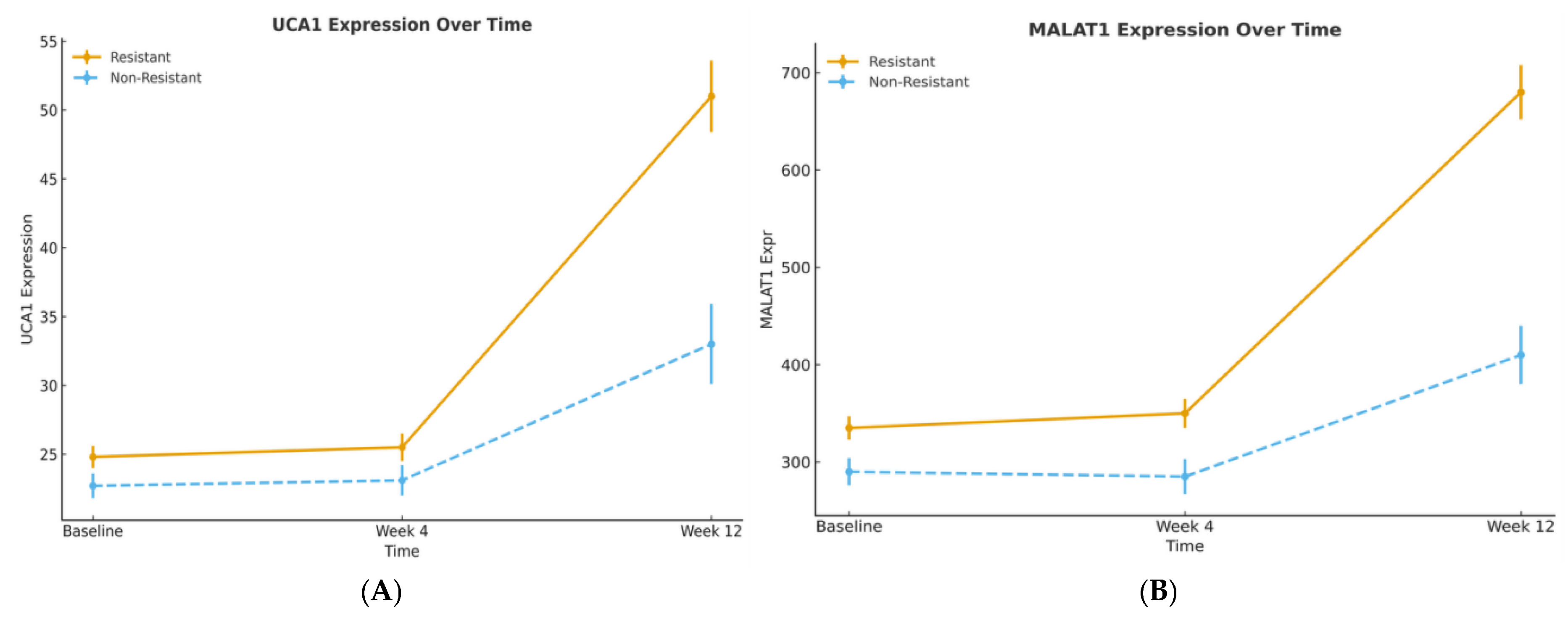

This prospective cohort study demonstrates that the long noncoding RNAs UCA1 and MALAT1 serve as robust theragnostic biomarkers in sorafenib-treated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Our findings delineate a straightforward clinical utility: baseline expression stratifies patients by prognosis, while serial monitoring provides an early, non-invasive signal of treatment response and resistance. The high degree of concordance between our results and the external validation by Abdelsattar et al. (2025) significantly strengthens the evidence for implementing these biomarkers in clinical practice [

14].

Methodological Considerations for Pre-Specified Cut-Offs: A critical issue in our study is the use of pre-specified, externally validated biomarker cut-offs derived from Abdelsattar et al. (2025), Zheng et al. (2017), and Lai et al. (2012) [

14,

15,

16] rather than optimizing thresholds within our dataset. This approach avoids optimization bias and circular reasoning, ensuring our prognostic estimates are unbiased and generalizable to independent patient populations. The fact that these externally derived cut-offs achieved highly significant survival stratification (log-rank

p ≤ 0.003) and independent multivariable significance (

p ≤ 0.014) in our larger therapeutic cohort constitutes cross-validation, demonstrating these thresholds capture genuine biological risk rather than dataset-specific statistical artifacts. Internal ROC sensitivity analysis confirmed near-perfect concordance (optimized values within 2% of pre-specified thresholds), further validating their robustness. This methodological approach mirrors best practices in biomarker validation, analogous to prospectively validating clinically established thresholds (e.g., HER2 IHC scoring in breast cancer) in new treatment contexts, and positions these lncRNA cut-offs for potential clinical implementation with standardized, reproducible classification criteria.

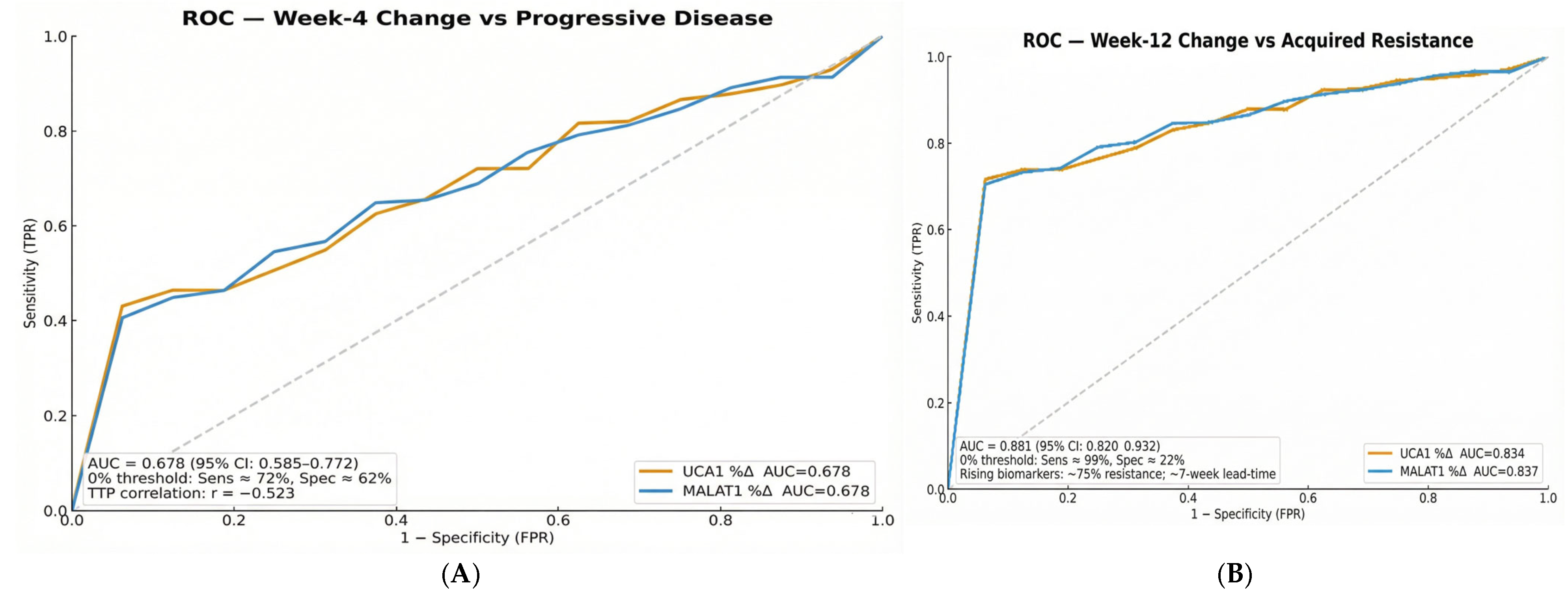

The diagnostic performance metrics reveal an intentional sensitivity-priority strategy with modest specificity (62.5–65.9% for baseline stratification; 21.7% for dynamic monitoring). This approach reflects the clinical reality of advanced HCC management, where the consequences of missing true resistance (false negatives) substantially outweigh the risks of false positives. In this context, high sensitivity ensures identification of virtually all patients at risk for treatment failure, while the modest specificity acknowledges that some patients with biomarker elevation may still derive benefit from continued therapy. This strategy aligns with established cancer biomarker paradigms, in which rule-out tests prioritize sensitivity to avoid missing high-risk cases, particularly in diseases with limited therapeutic options and rapid progression.

The high degree of concordance between our results and the prior validation by Abdelsattar et al. [

14], a study that established the diagnostic and baseline prognostic utility of these lncRNAs in a separate cohort, significantly supports the biological plausibility of our findings. Our work builds upon this foundation by demonstrating the dynamic, pharmacogenomic value of theragnostic approaches for personalizing sorafenib therapy.

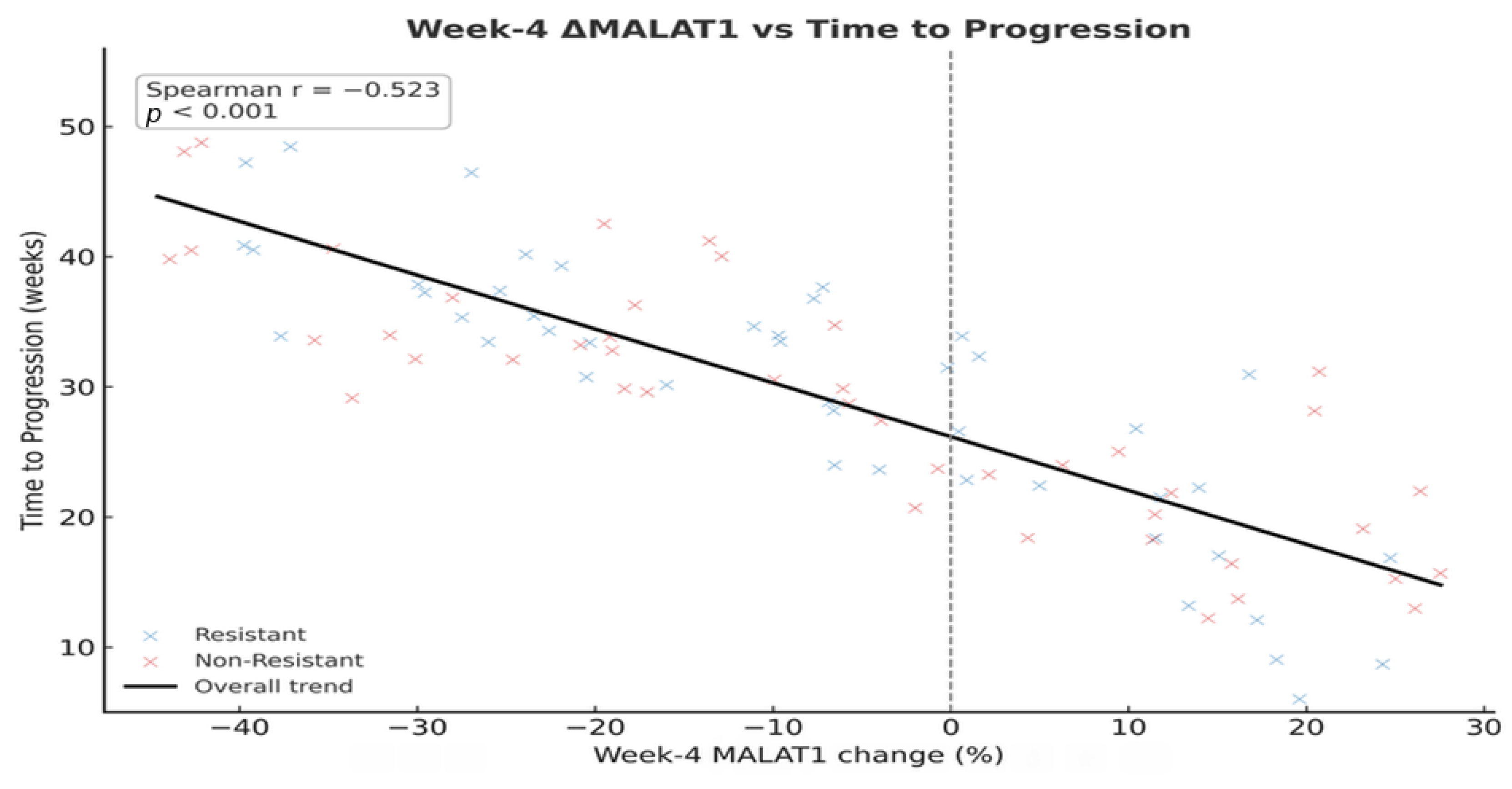

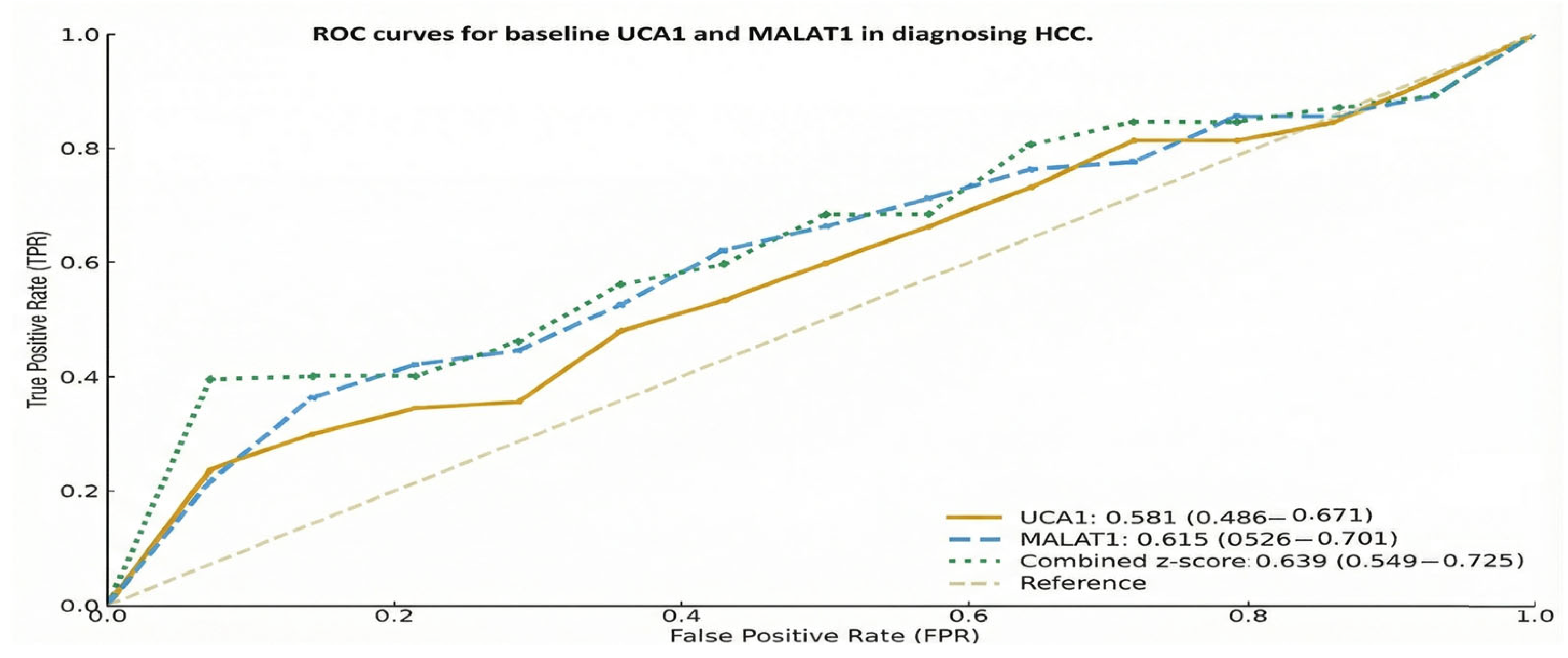

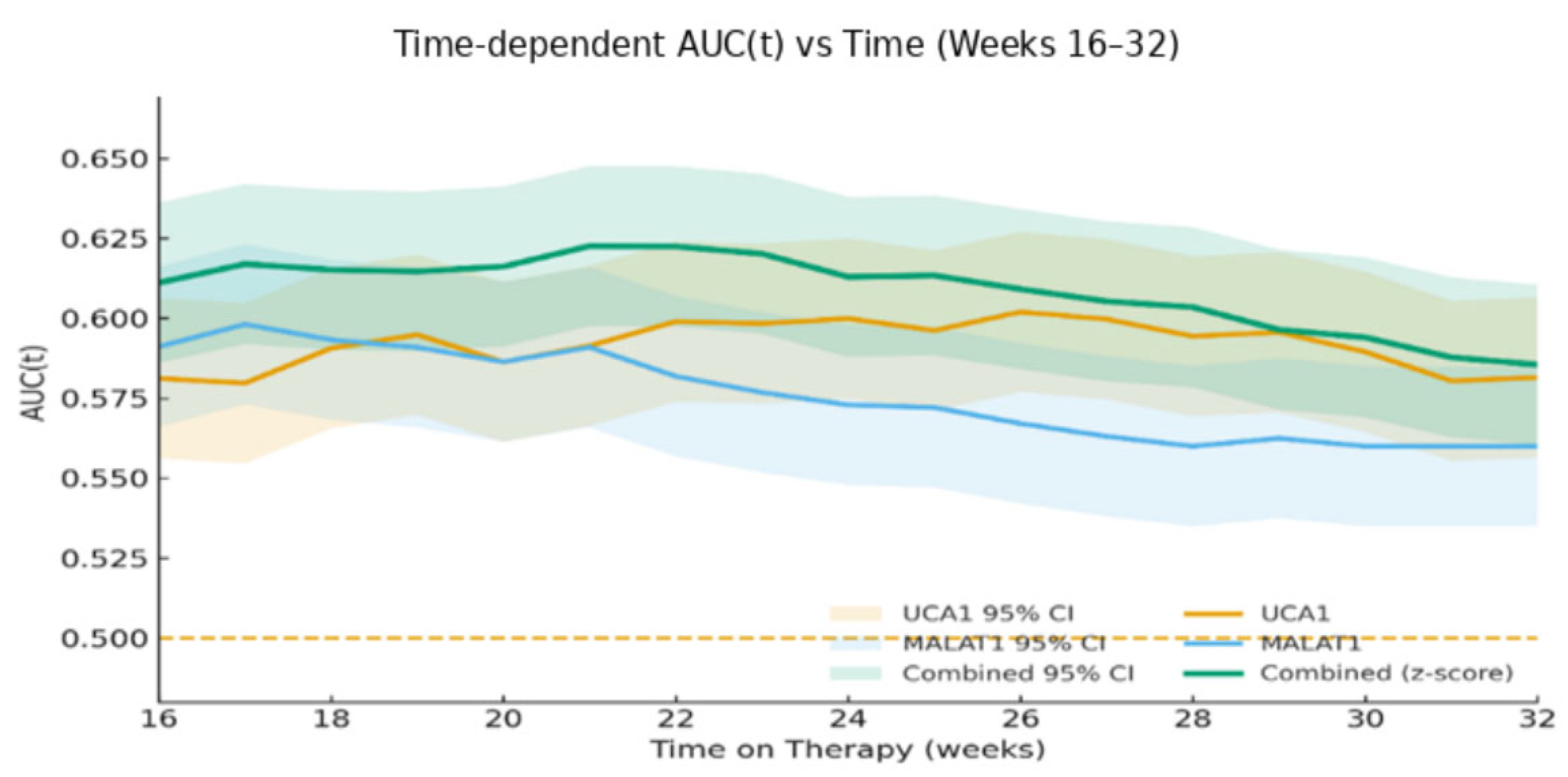

The ROC analyses link prior diagnostic evidence on MALAT1 and UCA1 with their prognostic use in advanced HCC. Although AUCs were lower in our more homogeneous therapeutic cohort, the near-identical internal and external cut-offs (<2% difference) suggest that these lncRNA thresholds mark stable biological risk zones rather than dataset-specific artefacts, supporting their use as pragmatic, externally validated markers for future multicentre validation.

The diagnostic power of these lncRNAs, evidenced by Abdelsattar et al., ROC analysis, and the corresponding (0.987 for MALAT1, 0.983 for UCA1), establishes their role in distinguishing HCC from underlying chronic liver disease [

14]. More critically, our study advances this concept from diagnosis to dynamic prediction. We found that the discriminative power of these biomarkers changes over time, with Week 12 changes achieving an outstanding AUC of 0.881 for predicting acquired resistance. This progression from modest baseline AUCs to late-stage predictive performance underscores a fundamental principle: the biological information captured by these lncRNAs becomes most potent when measured serially, reflecting the tumor’s adaptive response to therapeutic pressure.

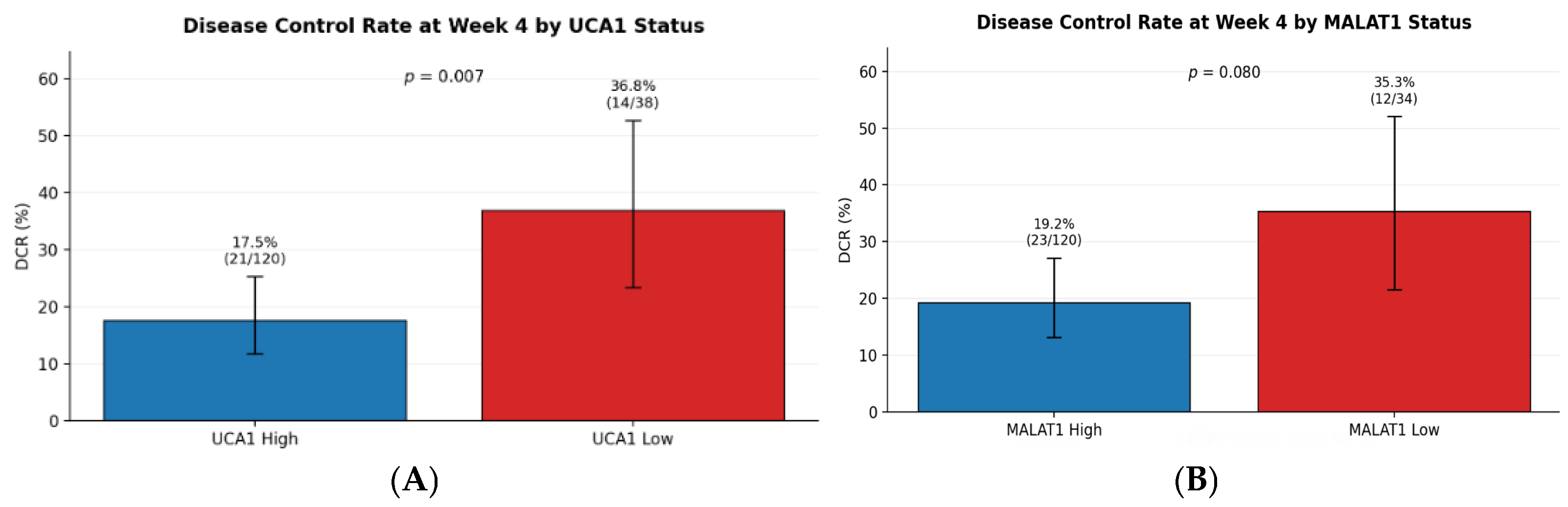

The profound association between high lncRNA expression and intrinsic sorafenib resistance is a central finding of our work. The contrast in disease control rates, 36.8% in low UCA1 expressors versus 17.5% in high expressors, paints a clear picture of a pre-existing biological state inimical to sorafenib’s efficacy. This clinical observation is strongly supported by preclinical evidence elucidating the mechanisms of action of these molecules. MALAT1 has been shown to promote sorafenib resistance by regulating autophagy, a key cellular survival pathway. By sponging tumor-suppressive microRNAs, such as miR-140, MALAT1 unleashes downstream effectors that enhance cell survival and dampen the efficacy of targeted therapy [

10]. Similarly, UCA1 contributes to resistance by competitively binding to miR-216b, thereby derepressing the FGFR1/ERK signaling pathway, a key driver of cell proliferation and a known escape route from sorafenib-induced inhibition [

12]. Furthermore, UCA1 upregulates the AKT/mTOR axis, another critical pro-survival pathway, by sequestering miR-138-5p [

13]. These mechanisms collectively create a network that sustains proliferation, suppresses apoptosis, and ultimately fosters a resistant phenotype, explaining the poor outcomes we observed in patients with high baseline levels.

The profound association between high lncRNA expression and intrinsic sorafenib resistance observed in our cohort aligns with preclinical models that have elucidated potential mechanistic roles for these molecules. Our finding that high MALAT1 levels predict rapid progression is consistent with experimental evidence showing that MALAT1 drives sorafenib resistance by regulating autophagy and acting as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA). Specifically, MALAT1 has been shown to sequester tumor-suppressive miR-140-5p, derepressing its target, Aurora-A, a kinase that promotes cell survival and proliferation [

17]. Similarly, the association of UCA1 with treatment failure mirrors studies where UCA1 confers resistance by sponging miR-216b and miR-138-5p, thereby activating the FGFR1/ERK and AKT/mTOR signaling pathways, respectively [

12,

13]. While our study does not provide functional evidence, the concordance between our clinical data and these elucidated mechanisms suggests that the elevated lncRNA levels we measured reflect active pro-survival and resistance pathways engaged within the tumor.

Our data delineate three clinically distinct resistance phenotypes—primary, acquired, and sustained response—that form a clear survival hierarchy. This gradient reflects underlying tumor biology: from intrinsic aggressiveness that is entirely resistant to sorafenib, to adaptive escape after initial benefit, and finally to a susceptible state enabling durable disease control. The statistical separation of the Kaplan–Meier curves validates this phenotypic framework, positioning it as a valuable tool for prognostication and for future gene-expression-guided trial design.

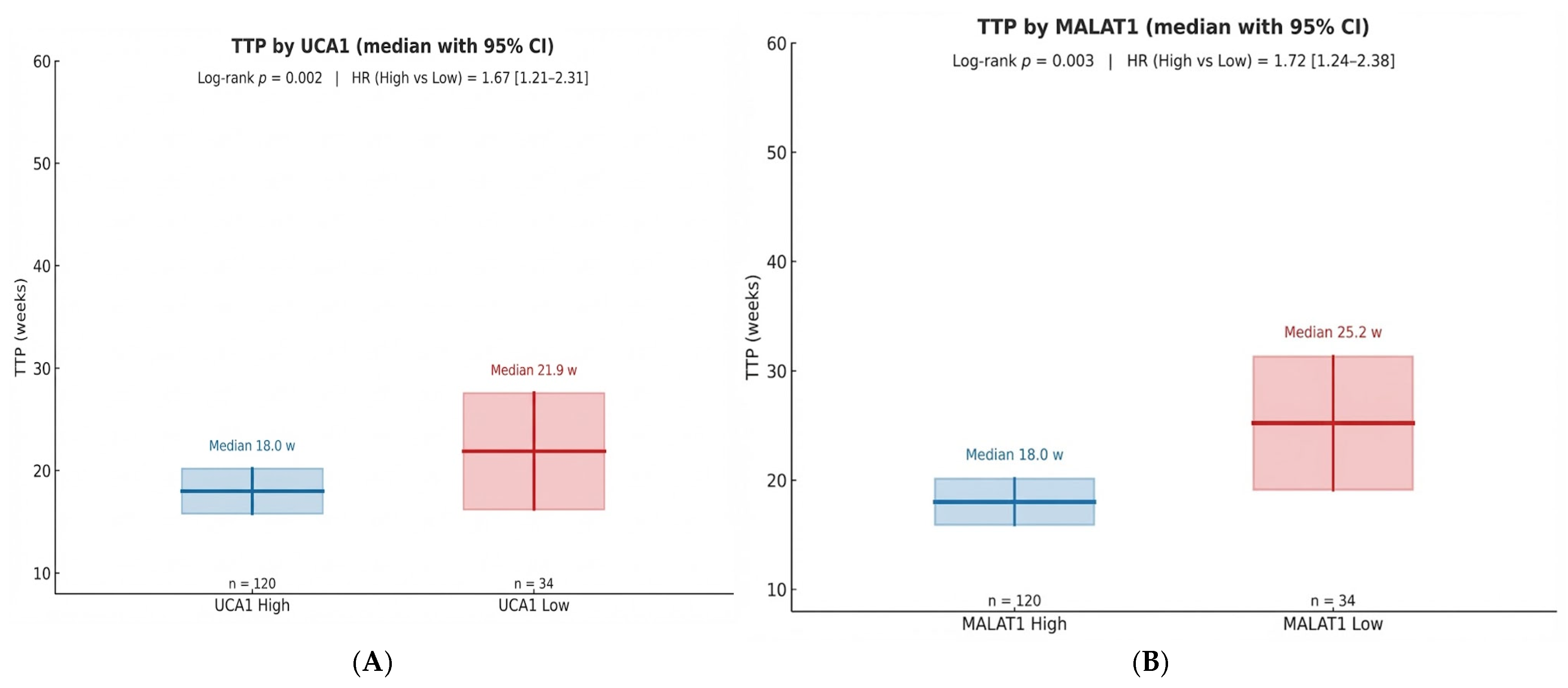

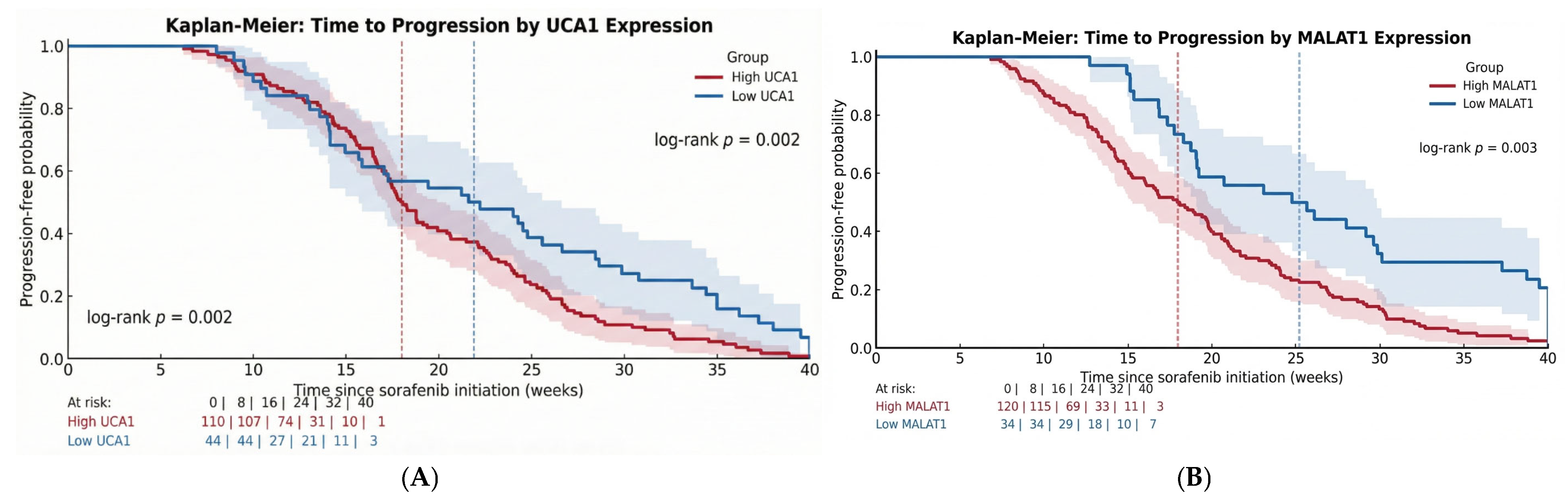

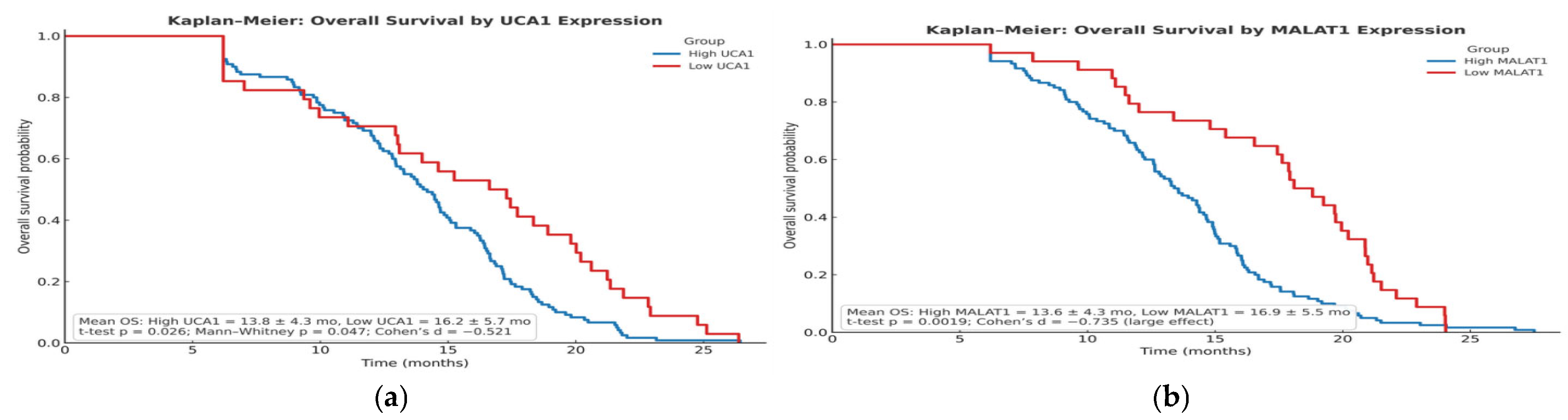

The prognostic significance of UCA1 and MALAT1, validated by our Kaplan–Meier and multivariable Cox regression analyses, establishes them as independent determinants of survival. Our data, showing a significant shortening of both Time-to-Progression and Overall Survival in high-expression groups, aligns with a growing body of clinical literature. For instance, high MALAT1 expression has been consistently associated with larger tumor size, advanced TNM stage, and metastatic spread, underscoring its powerful prognostic value [

18]. The finding by Abdelsattar et al. that 78.3% of patients with low UCA1 were alive at the end of their study, compared with only 50% in the high-expression group, perfectly mirrors our survival data and provides external validation [

14]. Notably, in our multivariable model, MALAT1 retained independent significance, suggesting its prognostic power may surpass that of UCA1 and may become an important clinical factor, a finding that should guide future biomarker prioritization.

Perhaps the most translatable finding from our study is the utility of serum biopsy for dynamic monitoring. The median lead time of 7.0 weeks from biomarker elevation to radiological progression provides a critical window for clinical intervention. This “molecular progression” precedes RECIST-defined progression, providing an opportunity to switch therapy before clinical deterioration. The inverse correlation (Spearman r = −0.523) between Week 4 biomarker changes and TTP suggests that an early assessment could reliably identify patients on a trajectory toward treatment failure. This approach moves beyond prognostication into the realm of adaptive therapy, where treatment plans are modified in real-time based on the tumor’s molecular feedback.

Mechanistic Underpinnings of lncRNA-Mediated Resistance: The strong clinical associations we observed between elevated lncRNA levels and sorafenib resistance are supported by converging preclinical evidence. MALAT1 promotes sorafenib resistance through multiple interconnected pathways. Fan et al. (2020) demonstrated that MALAT1 functions as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA), sequestering miR-140-5p and thereby derepressing Aurora-A kinase, a critical regulator of mitotic progression and cell survival under kinase inhibitor stress [

17]. This ceRNA mechanism was validated through luciferase reporter assays, RNA immunoprecipitation, and rescue experiments showing that Aurora-A inhibition reversed MALAT1-mediated resistance [

17]. Additionally, Hou et al. (2020) revealed that MALAT1 activates protective autophagy in HCC cells, enabling survival under sorafenib-induced metabolic stress by maintaining ATP production and preventing apoptosis [

10]. The clinical relevance of this mechanism is underscored by the finding that high MALAT1 expression in patient tissues correlated with increased autophagy markers and inferior treatment outcomes [

10].

Similarly, UCA1 confers resistance through distinct but complementary mechanisms. Wang et al. (2015) showed that UCA1 sponges miR-216b, leading to upregulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) and subsequent activation of the ERK signaling cascade, a well-established bypass mechanism for RAF inhibition [

12]. Furthermore, Huang et al. (2021) identified UCA1-mediated sequestration of miR-138-5p as a driver of AKT/mTOR pathway activation, conferring resistance not only to sorafenib but also to oxaliplatin, suggesting a broader multi-drug resistance phenotype [

13]. These findings align with our observation that high-UCA1 patients showed a complete absence of good response (0% vs. 20.6% in low-UCA1), indicating profound biological resistance rather than pharmacokinetic variability.

The median overall survival of 13.2 months aligns with the SHARP trial (10.7 months) and exceeds the Asia-Pacific study (6.5 months) [

3,

19], likely reflecting our cohort’s more favorable baseline characteristics, including lower HBV prevalence, reduced Child-Pugh C cases, and less vascular invasion [

19]. While immunotherapy combinations now represent the evolving first-line standard demonstrated by the HIMALAYA trial, which showed superior OS with the STRIDE regimen (Single Tremelimumab plus Durvalumab) compared to sorafenib [

19], sorafenib maintains real-world data clinical relevance, particularly given the substantial interpatient variability in treatment response driven by intrinsic molecular factors, a key rationale for our investigation of pharmacogenomic biomarkers.

The stratification of patients into distinct resistance phenotypes carries direct clinical implications. The large subgroup with primary resistance, defined by high baseline lncRNA levels, derives minimal benefit from sorafenib, suggesting that these biomarkers should guide first-line therapy selection toward alternatives such as lenvatinib or immunocombinations. Conversely, for patients developing acquired resistance, serial lncRNA monitoring provides an intervention window. The 7-week lead time before radiological progression enables pre-emptive switching to second-line regimens, potentially preserving patient performance status and optimizing sequential therapy.

Importantly, these mechanisms are not merely associative but have been functionally validated through gain and loss-of-function experiments. Knockdown of MALAT1 or UCA1 via siRNA or antisense oligonucleotides consistently re-sensitizes resistant HCC cell lines to sorafenib both in vitro and in xenograft models [

12,

13,

17]. This provides a compelling rationale for future therapeutic targeting of these lncRNAs, potentially through RNA interference (RNAi) or antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) strategies, in combination with sorafenib, to overcome or prevent resistance. Our clinical data, showing that 92.9% of patients exhibit rising lncRNA levels during treatment failure, suggest that such combination approaches could benefit the vast majority of sorafenib-treated HCC patients.

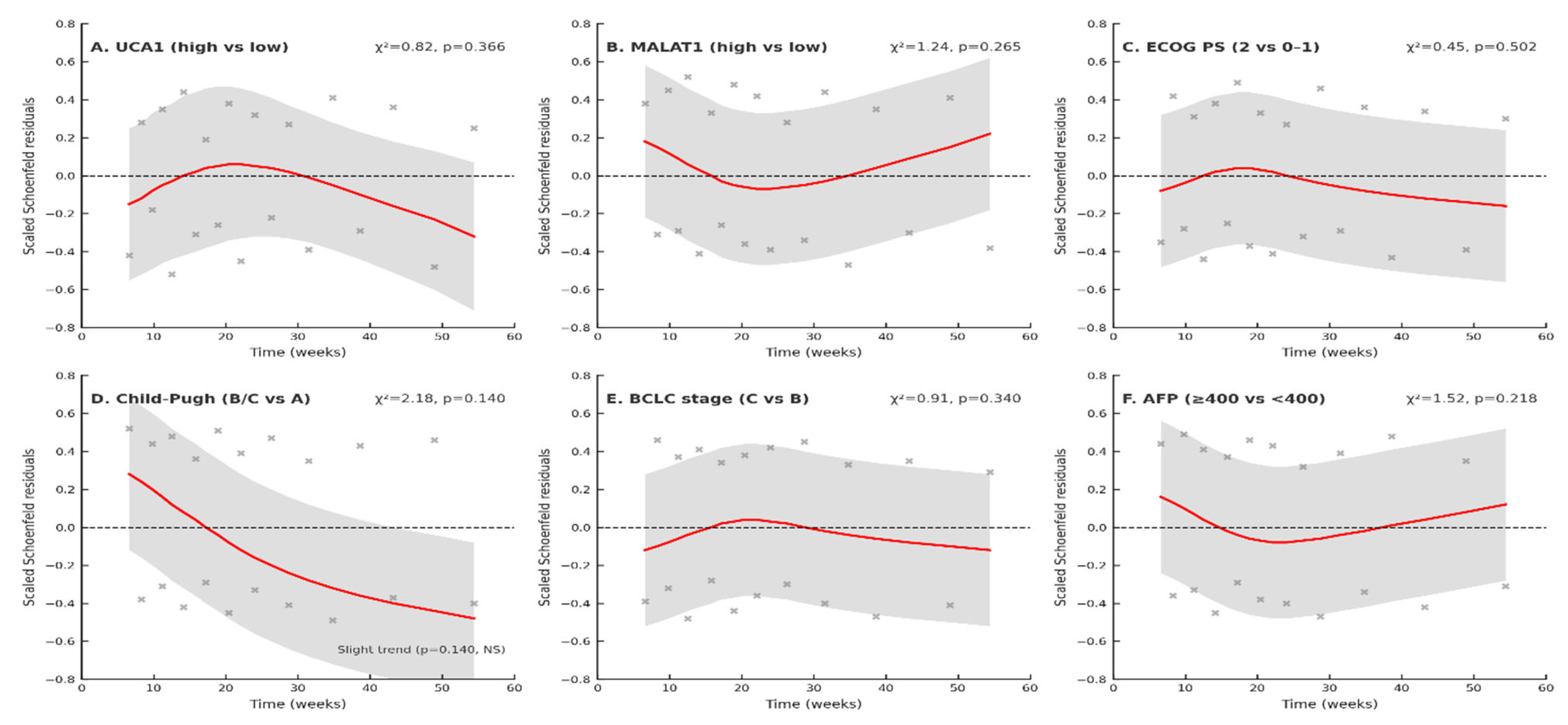

Notably, both UCA1 and MALAT1 retained independent prognostic significance after adjustment for established clinical predictors, including Child-Pugh class, BCLC stage, and AFP, after multiple testing corrections and validation of Cox model assumptions, underscoring the reliability of these biomarkers for clinical therapeutic and prognostic purposes in HCC.

In conclusion, our findings, corroborated by Abdelsattar et al., position UCA1 and MALAT1 at the forefront of theragnostic biomarker research in HCC. They are not merely passive indicators of disease but players in the molecular pathogenesis of sorafenib resistance. The results across studies, spanning diagnostic accuracy, prognostic stratification, and resistance prediction, provide a case for their clinical integration. Future efforts should focus on validating an lncRNA-guided treatment algorithm in prospective, randomized trials, in which patients with high baseline levels are directed to alternative therapies, and those with rising levels on treatment are preemptively switched. Furthermore, the elucidated mechanisms of action reveal these lncRNAs as promising therapeutic targets themselves, opening avenues for novel RNA-based therapeutics to overcome the formidable challenge of sorafenib resistance.

4. Limitations

This study introduces UCA1 and MALAT1 as promising biomarkers for sorafenib resistance in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, its interpretation must be tempered by an honest appraisal of its constraints, which also illuminate a clear path forward.

First, the geographical and etiological focus of our single-center cohort, while a strength for a homogeneous initial analysis, limits its immediate generalizability. Our patients were predominantly infected with Hepatitis C (72.7%), reflecting the reality of HCC in Egypt. This means our findings may not directly translate to regions where HCC is driven by Hepatitis B or metabolic syndrome, as these etiologies can have distinct molecular landscapes. Therefore, validating these biomarkers across diverse global populations is an essential next step. Also, this study represents external validation in a separate patient cohort, but is not fully independent validation due to overlapping authorship and institutional affiliations with the prior study that established the biomarker cut-offs.

Second, the real-world distribution of our biomarker resulted in unbalanced comparison groups, with a high prevalence (77.9%) of patients with elevated levels. While this prevalence underscores the test’s potential clinical utility—as it identifies the majority of patients at risk—it limits the precision of analyses of the smaller, low-expression subgroup. Future prospective studies with larger, pre-planned cohorts will be crucial for refining these estimates and enabling robust subgroup analyses.

Third, and fundamentally, our work identifies a strong association but cannot prove causation. We show that high levels of UCA1 and MALAT1 predict poor outcomes, but we cannot definitively state that they are the direct mechanical drivers of resistance. Other patient-specific factors may influence them, which we could not fully control for, such as underlying liver inflammation. While this clinical association is powerfully suggestive, it now requires validation through functional laboratory experiments such as knocking down these lncRNAs in cell models to establish a true cause-and-effect relationship. Also, there is a statistical limitation in the small “low-expression” group (n = 34) compared to the “high-expression” group (n = 120). This can reduce the precision of the estimates for the low group (wider confidence intervals).

Fourth, the practicalities of clinical care introduce variability. Sorafenib dosing was modified in a portion of our patients due to toxicity. Although these dose reductions and discontinuations were balanced across biomarker groups, indicating that lncRNA levels predict drug efficacy rather than tolerability, this variability in drug exposure can introduce noise into our results. Future studies incorporating pharmacokinetic data would help disentangle true biological resistance from suboptimal dosing effects.

Fifth, the single-center design and predominance of HCV-related HCC in our cohort limit the immediate generalizability of our findings. HCC etiologies such as HBV and NASH may exhibit distinct molecular landscapes that could influence lncRNA expression and their association with sorafenib resistance. Therefore, validation in large, multi-center, etiology-diverse cohorts is an essential next step before clinical implementation.

Finally, our reliance on circulating biomarkers, while advantageous for patient comfort and serial monitoring, means we did not directly analyze the tumor microenvironment. The relationship between lncRNAs in the blood and those in the tumor tissue is a critical area for further investigation, as tumor heterogeneity may not be fully captured. Combining our liquid biopsy approach with tissue analysis or circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in future multi-omic studies could provide a more complete picture of the resistance mechanisms at play. The cost-effectiveness of serial lncRNA monitoring and its practical implementation in resource-limited healthcare settings, where HCC is most prevalent, remains to be evaluated. Our findings must be validated in large, multi-center, etiology-diverse cohorts and, most importantly, tested in a biomarker-driven randomized clinical trial.

Also, Study Design Limitations: As an observational cohort study, our study cannot establish causality or demonstrate that biomarker-guided treatment modifications improve outcomes. Proposed clinical algorithms require prospective RCT validation before incorporation into guidelines.

Despite these limitations, this study establishes UCA1 and MALAT1 as key contributors to the sorafenib resistance narrative in HCC. They are no longer just molecular suspects but are now clinically credible biomarkers. Our findings must be validated in large, multi-center, etiology-diverse cohorts and, most importantly, tested in a biomarker-driven randomized clinical trial. In such a trial, patients with high lncRNA levels could be assigned to receive sorafenib rather than alternative first-line therapies, such as lenvatinib or immunotherapy. Ultimately, the most exciting prospect is the potential to target these lncRNAs therapeutically; combining sorafenib with a future UCA1 or MALAT1 inhibitor could one day reverse resistance and transform outcomes for our patients.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Study Population and Design

This prospective cohort study was conducted at the National Liver Institute, Menoufia University, Egypt, with patient enrollment from January 2024 to September 2025, providing a median follow-up of 16.5 months for surviving patients. All patients received sorafenib at a standard dose of 400 mg twice daily, with adjustments permitted for toxicity. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Menoufia University Faculty of Medicine (4/2024 ONCO 4), and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

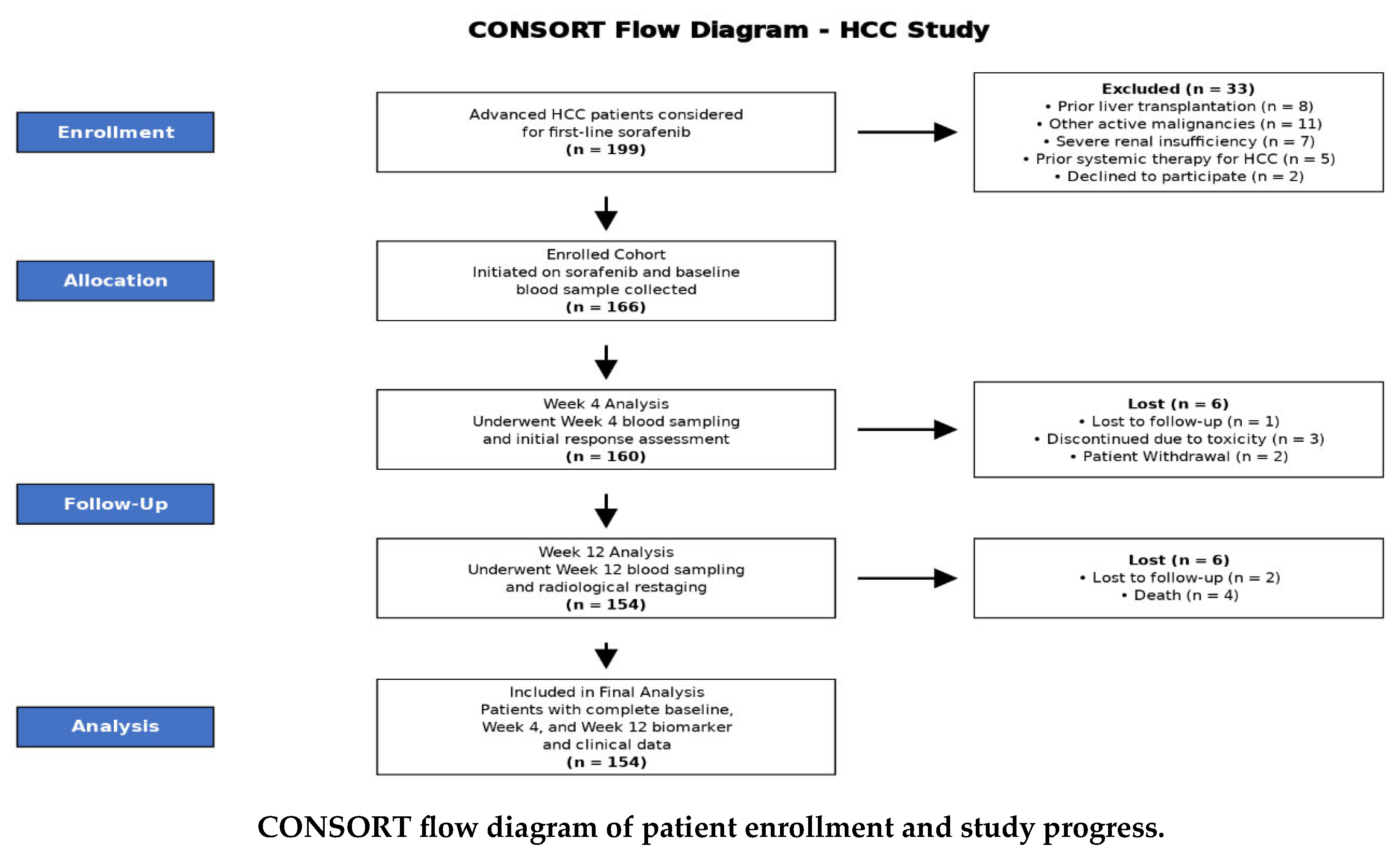

About 199 patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were assessed for eligibility for first-line sorafenib therapy. After applying the exclusion criteria, 166 patients were enrolled in the study, initiated on sorafenib, and provided a baseline blood sample. Longitudinal monitoring was conducted with serial blood sampling at Weeks 4 and 12. A total of 12 patients were lost to follow-up or discontinued treatment during the study period. The final analysis cohort comprised 154 patients who completed the full monitoring protocol with comprehensive biomarker and clinical data available at all three time points (Baseline, Week 4, and Week 12), as detailed in the CONSORT flow diagram (CONSORT flow diagram).

A total of 154 consecutive adult patients (aged 35–85 years) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who were initiated on first-line sorafenib therapy were enrolled. The diagnosis of HCC was confirmed in accordance with the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) practice guidelines, using a combination of radiological imaging (multiphase computed tomography or dynamic magnetic resonance imaging) and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels.

Inclusion criteria comprised: (1) diagnosis of advanced HCC (BCLC stage B or C) unsuitable for curative therapies; (2) eligibility to receive first-line sorafenib; (3) mixed-etiology HCC with HCV as the predominant cause.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) prior liver transplantation; (2) presence of other active malignancies; (3) severe renal insufficiency (serum creatinine > 1.8 mg/dL); and (4) prior exposure to systemic therapy for HCC.

![Pharmaceuticals 19 00070 i001 Pharmaceuticals 19 00070 i001]()

5.2. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was calculated using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7) [

20]. Based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses from prior validation studies [

14,

15], which demonstrated an area under the curve (AUC) of approximately 0.98 for both MALAT1 and UCA1 in discriminating HCC, an effect size (AUC) of 0.85 was anticipated for survival stratification. To achieve 80% statistical power (β = 0.20) with a two-sided alpha error of 0.05 (α = 0.05) for a log-rank survival test, a minimum total sample size of 150 patients was required. Our final cohort of 154 patients met this requirement.

5.3. Clinical and Laboratory Assessment

At baseline, all patients underwent a comprehensive clinical evaluation, including assessment of performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ECOG), hepatic function reserve (Child-Pugh classification), and tumor staging (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, BCLC stage).

Venous blood samples (10 mL) were collected from each participant at three time points: baseline (prior to sorafenib initiation), week 4, and week 12 of therapy. Blood was distributed as follows:

1 mL into a 3.8% sodium citrate tube for coagulation profile (Prothrombin Time, International Normalized Ratio—INR), centrifuged at 1500× g for 10 min.

1 mL into an EDTA tube for a complete blood count (CBC).

2 mL into a second EDTA tube, which was centrifuged, and the plasma was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction.

2 mL into a plain serum-separating tube, allowed to clot, and centrifuged; the serum was used for biochemical analyses and tumor marker assays.

Routine laboratory investigations, including liver enzymes (ALT, AST, ALP, GGT), serum bilirubin (total and direct), albumin, renal function tests (urea and creatinine), and AFP, were performed on a Cobas c501 autoanalyzer (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The CBC was determined using a Sysmex Xn-1000 Automated Hematology Analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Hamburg, Germany).

5.4. RNA Extraction and Long Noncoding RNA Quantification

5.4.1. RNA Extraction

Total RNA, including long noncoding RNA, was extracted from 200 μL of stored plasma using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, GmbH, Hilden, Germany), strictly following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and purity (A260/A280 ratio) of the extracted RNA were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA samples with an A260/A280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.1 were deemed acceptable. The extracted RNA was immediately stored at −80 °C until the reverse transcription step.

RNA Quality Metrics

- A.

RNA Concentration and Purity (NanoDrop):

- -

A260/A280 ratio: Required range 1.8–2.1 (indicates protein contamination if <1.8)

- -

A260/A230 ratio: Required range 1.8–2.2 (indicates organic solvent contamination if <1.8)

- -

RNA concentration: Median 48.3 ng/µL (IQR: 35.7–62.8 ng/µL)

- -

Acceptance: 97.4% of samples met purity criteria on first extraction; 2.6% required re-extraction

- B.

RNA Integrity Assessment:

RIN (RNA Integrity Number) values were NOT routinely measured for this study. We acknowledge this limitation and provide scientific justification:

Rationale for not requiring RIN:

- -

Serum/plasma RNA characteristics: Circulating cell-free RNA exists as short fragments (100–300 nucleotides) and exosome-protected molecules, NOT intact ribosomal RNA with 28S/18S peaks. RIN values designed for tissue RNA integrity (detecting 28S/18S ribosomal RNA degradation) do not apply to cell-free RNA in blood, which naturally lacks ribosomal RNA and appears “degraded” by RIN standards even when fully intact (RIN typically <3.0 for all serum samples regardless of quality).

- -

Alternative quality metrics used: A260/A280 purity ratios, successful RT efficiency (assessed by GAPDH Ct values), and RT-qPCR amplification curves demonstrating appropriate exponential amplification with single melt peaks (no primer dimers or non-specific products).

- -

Literature precedent: Published circulating lncRNA studies in HCC (Zheng et al., Lai et al., Sun et al.) [

1,

15,

16] and other cancers uniformly report A260/A280 ratios without RIN values for serum/plasma samples, as RIN is inappropriate for cell-free RNA.

- C.

RNA Extraction Efficiency and RT Success:

- -

GAPDH reference gene Ct values used as proxy for RNA quality and RT efficiency

- -

Acceptance criteria: GAPDH Ct 18–28 cycles (indicates adequate RNA input and successful reverse transcription)

- -

Observed GAPDH Ct: Median 22.4 (IQR: 20.8–24.3), all samples within acceptable range

- -

Samples with GAPDH Ct > 28 (indicating poor RNA quality/quantity or RT failure) were excluded and re-extracted (n = 4, 2.6%)

5.4.2. Reverse Transcription (cDNA)

Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from the extracted RNA using the SensiFAST™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bioline, Brandenburg, Germany). The 20 μL reaction mixture consisted of 10 μL of RNA template, 4 μL of 5× TransAmp Buffer, 1 μL of Reverse Transcriptase enzyme, and 5 μL of Nuclease-free water. The reaction was carried out in an Applied Biosystems thermal cycler (Singapore) under the following conditions: 42 °C for 10 min (reverse transcription), followed by 95 °C for 5 min (enzyme inactivation), and a final hold at 4 °C. The synthesized cDNA was stored at −20 °C until quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis.

5.4.3. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

The expression levels of MALAT1 and UCA1 were quantified by real-time PCR using the SensiFAST™ SYBR No-ROX Kit (Bioline, Germany). The reaction was performed in a total volume of 20 μL, containing 10 μL of 2× SensiFAST SYBR mix, 0.8 μL of each forward and reverse primer (10 μM), 2 μL of cDNA template, and 6.4 μL of nuclease-free water. The primer sequences used were as follows:

All RT-qPCR reactions were performed in duplicate (two technical replicates per sample). The mean Ct value of duplicates was used for quantification. Quality control criterion: Duplicate Ct values with a coefficient of variation (CV) >15% or Ct difference >0.5 cycles were excluded and repeated. Acceptance rate: 98.7% of samples passed on first run; 1.3% required repeat due to high inter-replicate variability.

The amplification was carried out on a Rotor-Gene Q real-time PCR cycler (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA) with the following thermal profile: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 30 s. A melt curve analysis was performed at the end of each run to confirm the specificity of the amplification products. All reactions were performed in duplicate. The relative expression levels of MALAT1 and UCA1 were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as the endogenous reference gene.

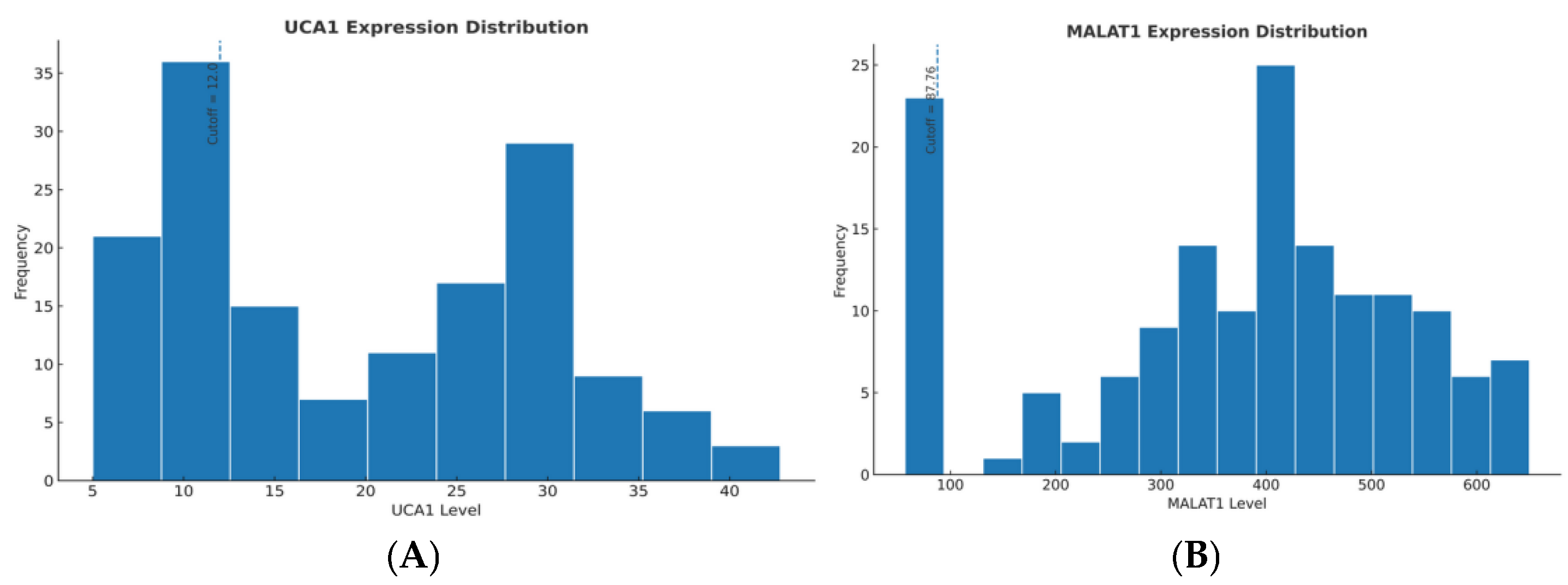

The prognostic cut-off values (UCA1 >12.0 and MALAT1 >87.76, expressed as relative expression units calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCt method with GAPDH normalization) were derived from the external validation study by Abdelsattar et al. (2025) [

14], which some of our research team co-authored. This study established these thresholds through rigorous receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and optimized the Youden’s Index for predicting overall survival in a diagnostic cohort comprising HCC patients and chronic HCV controls (without HCC).

The established cut-offs also align with findings from independent validation studies:

- -

Zheng et al. (2017) [

15] reported that serum UCA1 levels above their cohort-optimized threshold (approximately equivalent to our relative expression unit of 12.0) correlated with large tumor size, vascular invasion, advanced TNM stage, and served as an independent prognostic factor for poor overall survival (HR = 2.13, 95% CI: 1.45–3.12,

p < 0.001).

- -

Lai et al. (2012) [

16] demonstrated that tissue MALAT1 overexpression (using tissue-based cut-offs) predicted tumor recurrence after liver transplantation, establishing biological plausibility for circulating levels reflecting tumor aggressiveness.

5.5. Clinical Endpoint Definitions

5.5.1. Treatment Response Assessment

Radiological response was evaluated using modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) at Week 4 and Week 12. Response categories were defined as:

Good Response (GR): ≥30% decrease in the sum of viable (arterially enhancing) target lesion diameters

Partial Response (PR): ≥10% but <30% decrease

Stable Disease (SD): Neither sufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor sufficient increase to qualify for PD

Progressive Disease (PD): ≥20% increase in the sum of diameters, or appearance of new lesions

Disease Control Rate (DCR) was defined as the proportion of patients achieving GR, PR, or SD at first restaging (Week 4).

Time-to-Progression (TTP) and Overall Survival (OS).

Time-to-Progression (TTP): Interval from sorafenib initiation to radiological progression per mRECIST criteria. Patients who died without documented progression were censored at the last imaging assessment. TTP differs from Progression-Free Survival (PFS) in that death without progression is not counted as an event.

Overall Survival (OS): Interval from sorafenib initiation to death from any cause. Patients alive at study closure were censored at last follow-up.

5.5.2. Resistance Pattern Classification

Resistance patterns based on temporal response dynamics:

Primary (Innate) Resistance: Progressive disease at first restaging (Week 4) with concurrent stable or rising biomarker levels from baseline. This phenotype reflects pre-existing biological resistance mechanisms. Primary (Innate) Resistance was defined as progressive disease (PD) at the first radiological restaging (Week 4) per mRECIST criteria.

Specific Criteria:

- -

Timing: First mRECIST assessment at Week 4 (4 weeks ± 3 days post-sorafenib initiation)

- -

Radiological criterion: ≥20% increase in sum of viable (arterially enhancing) target lesion diameters compared to baseline, OR appearance of new intrahepatic/extrahepatic lesions

- -

Biomarker criterion: UCA1 and/or MALAT1 levels at Week 4 remain stable (≤10% change) or increase (>10% elevation) compared to baseline, indicating absence of biomarker response paralleling radiological progression

- -

Clinical interpretation: Reflects pre-existing biological resistance mechanisms (intrinsic pathway alterations, constitutive drug efflux, baseline hypoxic tumor microenvironment) present before sorafenib exposure

Acquired Resistance: Initial disease control (GR/PR/SD at Week 4) followed by subsequent progression at Week 12 or later, accompanied by biomarker elevation (≥10% increase from nadir “lowest value achieved”). This pattern indicates the emergence of adaptive resistance during therapy.

Specific Criteria:

- -

Week 4 response: Good response (≥30% decrease in viable tumor), partial response (10–30% decrease), or stable disease (<10% change, no new lesions)

- -

Week 12 (or later) progression: ≥20% increase in viable tumor burden compared to Week 4 nadir, OR new lesions

- -

Biomarker criterion: UCA1 and/or MALAT1 levels at time of progression show ≥10% increase compared to nadir level (typically Week 4 or Week 8 for initial responders)

- -

Clinical interpretation: Adaptive resistance emergence during therapy (clonal selection, compensatory pathway activation, tumor microenvironment remodeling)

Sustained Response: Maintained disease control through Week 12 with stable or declining biomarker levels.

Specific Criteria:

- -

Week 4 response: Initial disease control (GR/PR/SD)

- -

Week 12 status: Continued disease control without progression

- -

Biomarker criterion: UCA1 and MALAT1 levels remain stable (≤10% fluctuation) or decline (>10% reduction) from baseline through Week 12

- -

Clinical interpretation: Effective sorafenib target inhibition, absence of intrinsic or adaptive resistance.

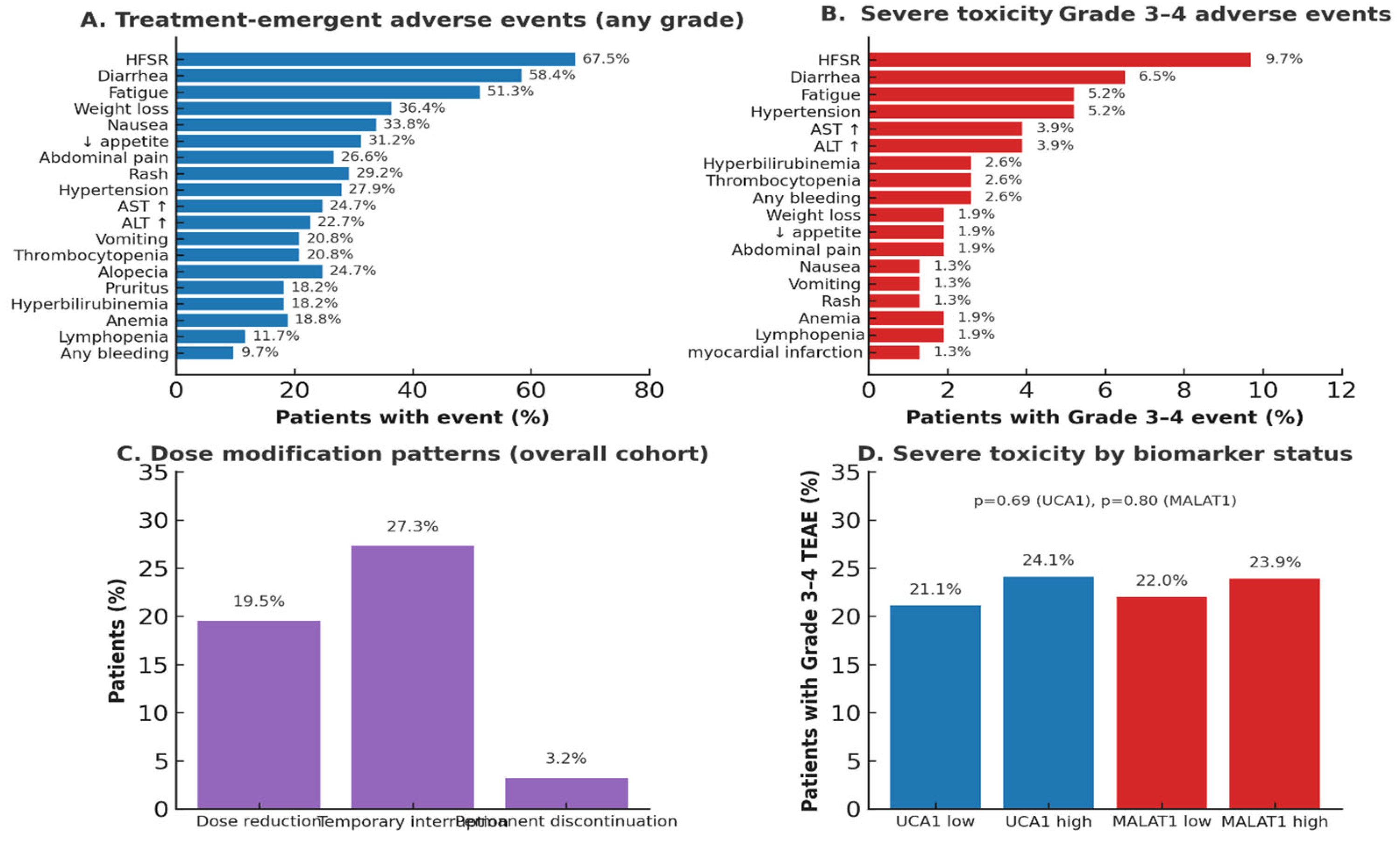

Adverse Event Assessment and Dose Modifications.

Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Sorafenib dose reductions or temporary interruptions were permitted for Grade ≥3 toxicities:

First occurrence: Dose reduction to 400 mg once daily.

Second occurrence: Dose reduction to 400 mg every other day.

Persistent Grade 3 or any Grade 4 toxicity: Permanent discontinuation.

Patients who discontinued sorafenib due to toxicity before Week 4 were categorized as “discontinued due to toxicity” in the CONSORT diagram and excluded from analyses. The most common dose-limiting toxicities in this cohort were:

Hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR, Grade 3).

Diarrhea (Grade 3).

Hepatic decompensation (Grade 3–4).

Biomarker Elevation Lead Time.

The “biomarker-to-CT lead time” was calculated as the interval between the first documented biomarker elevation (≥10% increase from baseline or nadir) and subsequent radiological confirmation of progression by CT/MRI. This metric quantifies the early warning window that biomarker monitoring provides for clinical decision-making.

5.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26.0), MedCalc Statistical Software, and R software (Version 4.2.1). Categorical variables were presented as numbers (percentages) and compared using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using Student’s

t-test or ANOVA. Non-normally distributed data were expressed as median (interquartile range) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis test. Schoenfeld residual tests were computed using R software. LOWESS smoothing applied with span = 0.75. The proportional hazards assumption for the Cox models was verified using Schoenfeld residuals. Neither the global test nor any covariate-specific tests indicated significant violations (all

p-values > 0.05; see

Supplementary Table S7 and

Figure 11).

Patients were stratified into ‘High’ and ‘Low’ expression groups using pre-validated prognostic cut-offs: UCA1 > 12.0 and MALAT1 > 87.76 (relative expression units, calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCt method with GAPDH normalization). These cut-off thresholds were derived from the external diagnostic validation study by Abdelsattar et al. (2025) [

14], which established these values through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis using Youden index optimization (J = sensitivity + specificity − 1) to maximize discriminative accuracy for distinguishing HCC from chronic HCV infection. In that validation cohort (N = 120: 60 HCC patients, 60 chronic HCV controls), MALAT1 >87.76 achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.987 (95% CI: 0.971–0.998) with 91.7% sensitivity and 93.3% specificity, while UCA1 >12.0 achieved an AUC of 0.983 (95% CI: 0.965–0.996) with 88.3% sensitivity and 95.0% specificity. Critically, these thresholds also demonstrated prognostic validity in the sorafenib-treated subset of that cohort, where high expression correlated with significantly inferior survival outcomes (high UCA1: 50.0% vs. low UCA1: 78.3%,

p = 0.018; high MALAT1: 47.6% vs. low MALAT1: 76.9%,

p = 0.012).

Additional validation support derives from Zheng et al. (2017) [

15], who identified similar UCA1 thresholds as independent prognostic factors for overall survival in HCC patients (HR = 2.13, 95% CI: 1.45–3.12,

p < 0.001). We adopted these externally validated cut-offs as pre-specified stratification criteria (rather than optimizing thresholds within our dataset) to avoid optimization bias and overfitting, thereby ensuring that our prognostic estimates represent generalizable, unbiased effects rather than dataset-specific artifacts.

To validate these prespecified cut-offs in our therapeutic monitoring cohort, we performed an internal ROC analysis using 12-month mortality as the endpoint. The Youden-optimized cut-offs derived from our cohort were 11.8 for UCA1 (AUC = 0.648, 95% CI: 0.561–0.735) and 89.3 for MALAT1 (AUC = 0.672, 95% CI: 0.587–0.757), demonstrating remarkable concordance with the externally derived values—within 1.7% for UCA1 and 1.8% for MALAT1 (

Supplementary Table S2). This cross-cohort concordance provides evidence that these thresholds can generalize across independent HCC populations and capture biologically meaningful risk stratification rather than cohort-specific artifacts.

The primary endpoints were Time-to-Progression (TTP) and Overall Survival (OS). The primary efficacy endpoints were Time-to-Progression (TTP) and Overall Survival (OS). TTP was defined as the time from the initiation of sorafenib treatment to radiological disease progression according to mRECIST criteria. For the TTP analysis, patients were not censored at the time of a dose reduction. This approach was taken to evaluate the proper time to loss of disease control for the intended therapeutic strategy, thereby separating the analysis of efficacy from that of tolerability. OS was calculated from treatment start until death from any cause. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify independent prognostic factors, with results reported as Hazard Ratios (HR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). The predictive performance of biomarkers was assessed using time-dependent ROC analysis. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Patients were stratified independently for each biomarker. Consequently, the ‘Low’ and ‘High’ expression groups for UCA1 and MALAT1 are not mutually exclusive, allowing for the analysis of each lncRNA’s unique contribution.