Network Pharmacology and Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis of the Protective Mechanisms of Total Flavonoids from Chuju in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Preparation and Composition Analysis of TFCJ

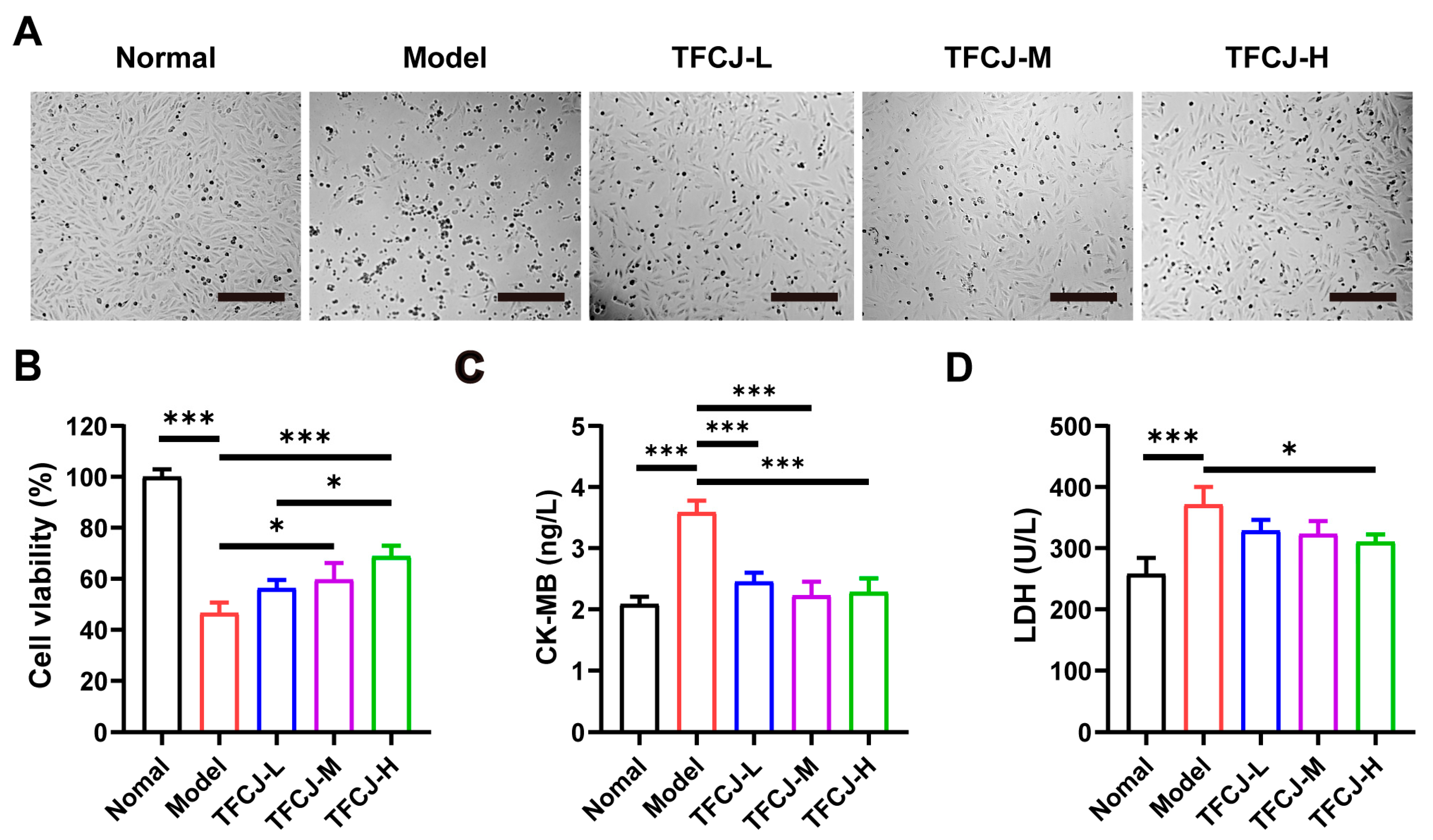

2.2. Effect of TFCJ on H/R-Induced Damage in H9c2 Cells

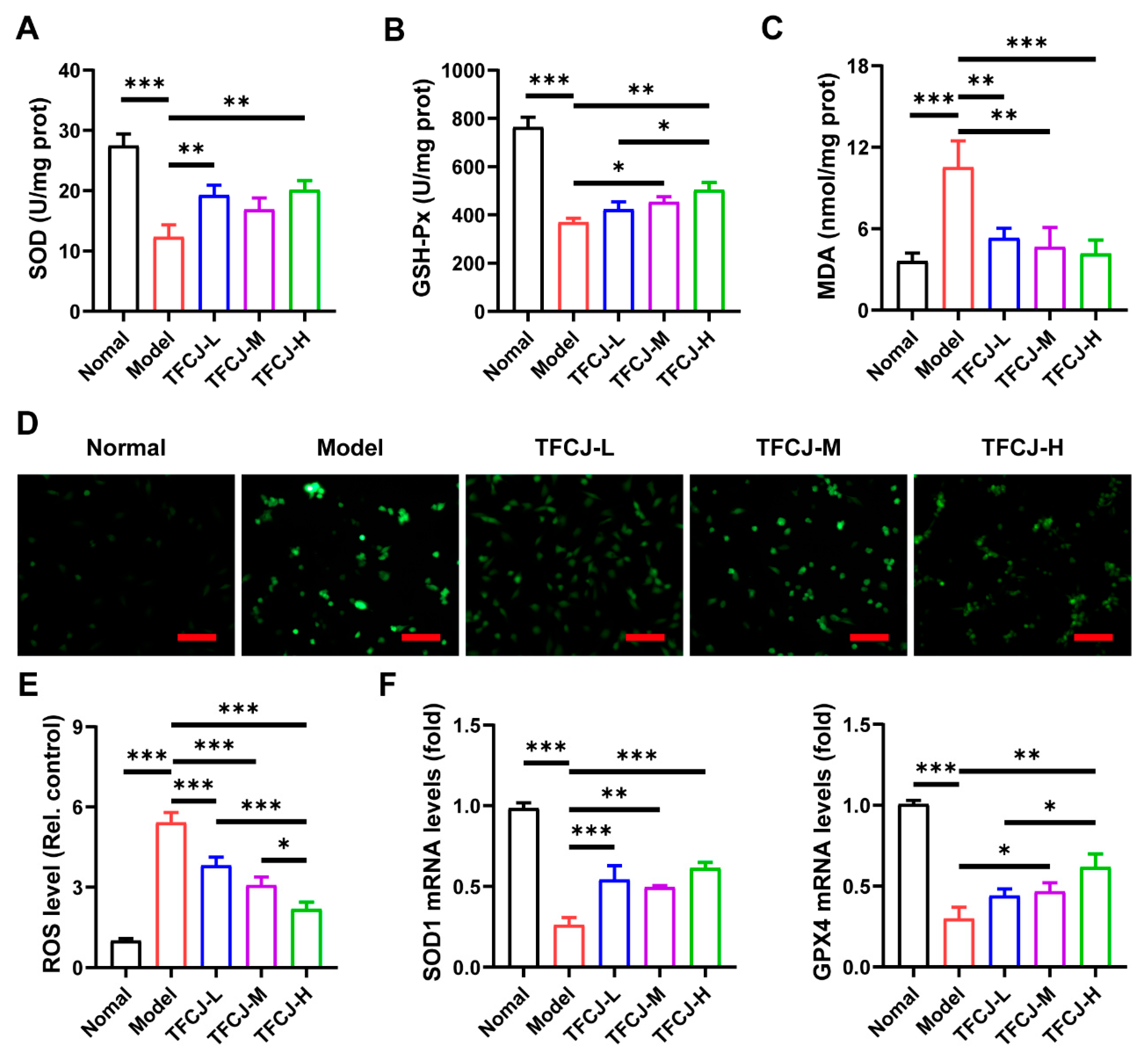

2.3. Effects of TFCJ on Oxidative Damage in H9c2 Cells

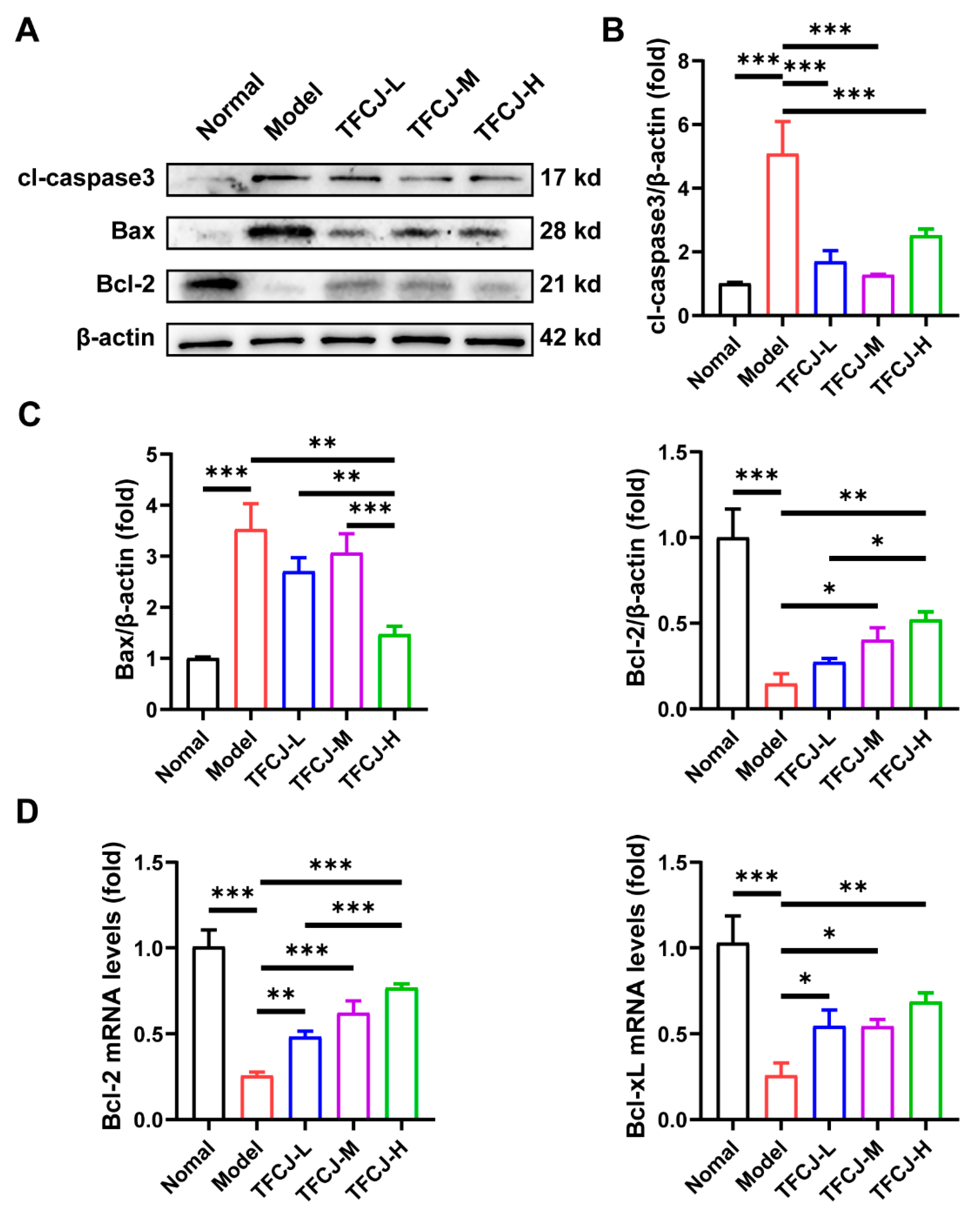

2.4. Effect of TFCJ on the Expression of Apoptotic Proteins in H9c2 Cells

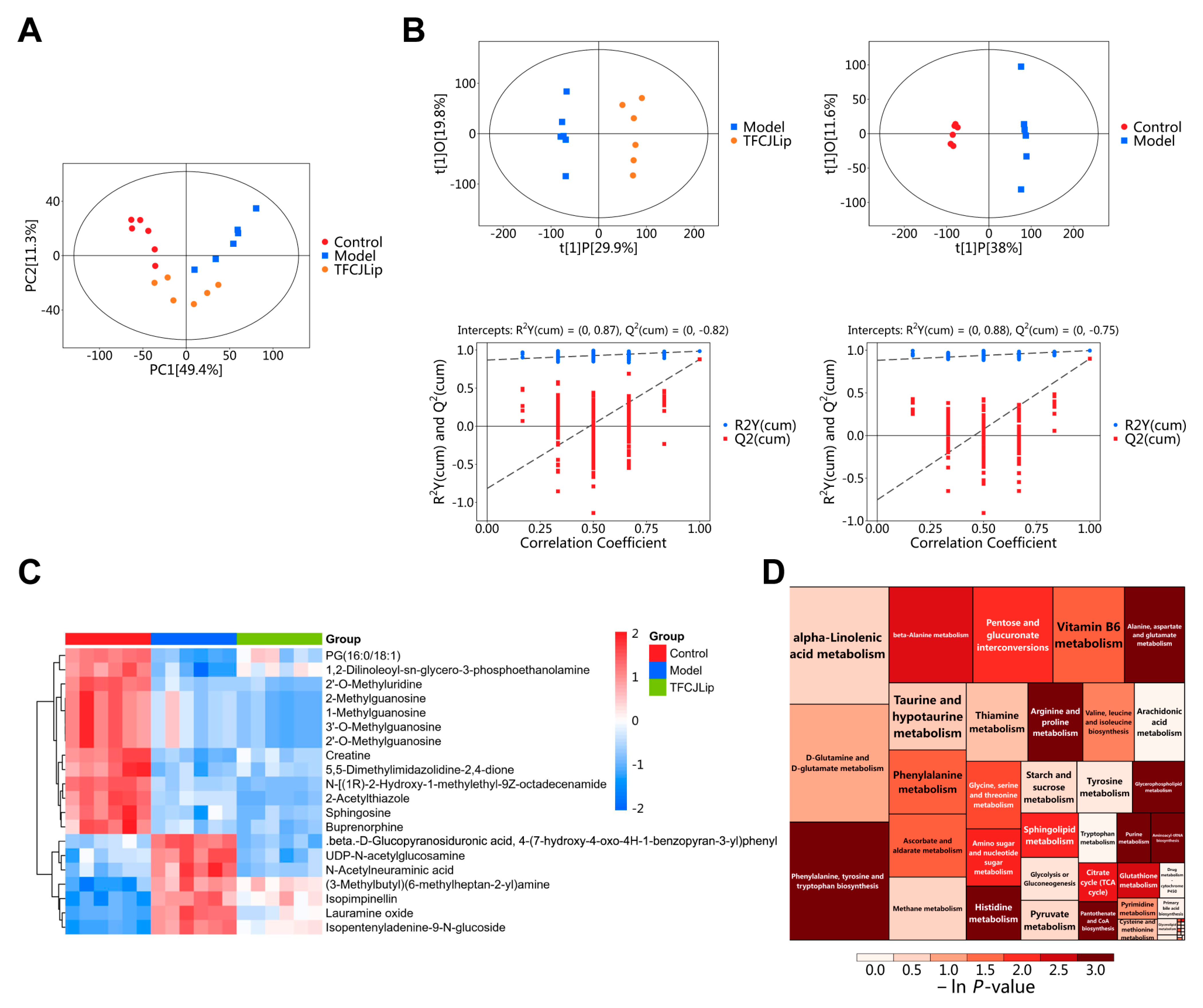

2.5. Metabolomic Analysis

2.5.1. PCA and OPLS-DA Analysis

2.5.2. Screening of Differential Metabolites

2.5.3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Differential Metabolites

2.6. Results of the Network Pharmacology Analysis

2.6.1. Prediction of Active Components and Targets of TFCJ

2.6.2. Subsubsection Collection of Targets for the Prevention and Treatment of MIRI by TFCJ

2.6.3. Construction of the PPI Network

2.6.4. Establishment of the “Drug-Component-Disease-Target” Network

2.6.5. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

2.7. Results of Molecular Docking

2.8. Integrated Analysis of Metabolomics and Network Pharmacology

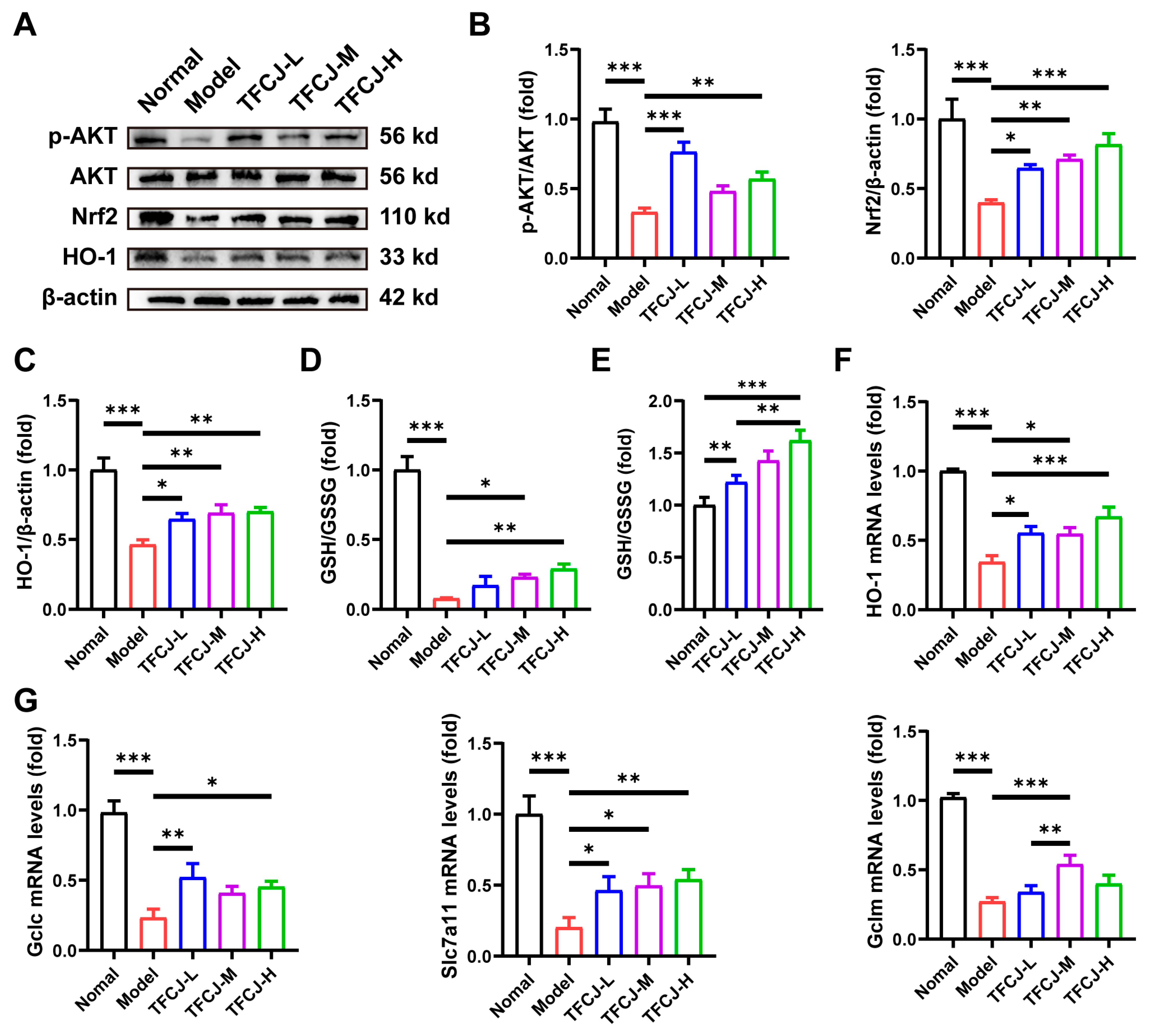

2.9. TFCJ Upregulates the Levels of Antioxidant Genes and GSH in H9c2 Cells by Activating AKT-Nrf2

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cells and Reagents

4.2. Preparation and Content Determination of TFCJ

4.3. Grouping and Model Establishment

4.4. Cell Viability Assay

4.5. Measurement of Cellular CK-MB and LDH Levels

4.6. Measurement of Cellular SOD, MDA, GSH-Px, and GSH Levels

4.7. Detection of ROS

4.8. qPCR

4.9. Western Blotting

4.10. Metabolomics Analysis

4.10.1. Metabolomics Sample Preparation

4.10.2. LC-MS/MS

4.10.3. Data Analysis and Statistical Processing

4.11. Network Pharmacology Analysis

4.12. Molecular Docking

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MIRI | Myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury |

| TFCJ | Total flavonoids of Chuju |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione peroxidase |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| CK-MB | Creatine kinase isoenzymes |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis |

References

- Sagris, M.; Apostolos, A.; Theofilis, P.; Ktenopoulos, N.; Katsaros, O.; Tsalamandris, S.; Tsioufis, K.; Toutouzas, K.; Tousoulis, D. Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: Unraveling Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Emerging Prevention Strategies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Allen, N.B.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Bansal, N.; Beaton, A.Z.; et al. 2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025, 151, e41–e660. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Yan, F.; Luan, F.; Chai, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.W.; Chen, Z.L.; Xu, D.Q.; Tang, Y.P. The pathological mechanisms and potential therapeutic drugs for myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Phytomedicine 2024, 129, 155649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, B.; Fu, Q.; Li, J. Advances in Chinese herbal medicine in modulating mitochondria to treat myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: A narrative review. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2025, 15, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y.; Daniyal, M.; Jian, Y.; Peng, C.; Shen, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, W. The flower head of Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat. (Juhua): A paradigm of flowers serving as Chinese dietary herbal medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 261, 113043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Xu, X.; Xia, D. Chemical Components, Pharmacological Effects of Chrysanthemum morifolium’Chuju’and Predictive Analysis on Its Quality Markers. Trad. Chin. Drug Res. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 36, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Ma, W.; Li, N.; Wang, K.-J. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Flavonoids from the Flowers of Chuju, a Medical Cultivar of Chrysanthemum Morifolim Ramat. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2018, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, H.; Jiang, H.H.; Mao, B.B.; Yu, H. Total Flavonoids of Chuju Decrease Oxidative Stress and Cell Apoptosis in Ischemic Stroke Rats: Network and Experimental Analyses. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 772401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, W.; Hao, C.; Feiyue, L.; Hao, Y. Effects of Total Flavonoids of Chuju on Focal Cerebral Ischemia-reperfusion Injury in Rats. J. Anhui Sci. Technol. Univ. 2021, 35, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Xiao, X.; Liu, H.; Zhou, J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, X. Effect of Total Flavonoids from Dendranthema morifolium (Ramat) Tzvel. cv. Chuju Flowers on Myocardial Ischemia Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Food Sci. 2012, 33, 283–286. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Li, T.; Wang, M.; Fang, W.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Yu, H. Study on Antioxidant Effects of Compatibility of Total Flavonoids and Polysaccharides from Chuzhou Chrysanthemum in Vivo and in Vitro. J. Anhui Sci. Technol. Univ. 2020, 34, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Guan, Y.; Du, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xie, H.; Lu, K.; Kang, J.; Jin, P. Exploiting omic-based approaches to decipher Traditional Chinese Medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Che, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X. Application of multi-omics in the study of traditional Chinese medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1431862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mao, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. Advancing Traditional Chinese Medicine Research through Network Pharmacology: Strategies for Target Identification, Mechanism Elucidation and Innovative Therapeutic Applications. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2025, 53, 2021–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, F.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Chai, K.; Liu, J.; Lei, H.; Lu, P.; et al. Network pharmacology: A crucial approach in traditional Chinese medicine research. Chin. Med. 2025, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Xiao, L.; Zheng, L.; Du, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhou, J.; Xiang, J.; Hou, J.; Wang, X.; Fang, J. An integration of UPLC-DAD/ESI-Q-TOF MS, GC-MS, and PCA analysis for quality evaluation and identification of cultivars of Chrysanthemi Flos (Juhua). Phytomedicine 2019, 59, 152803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netala, V.R.; Hou, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Teertam, S.K. Cardiovascular Biomarkers: Tools for Precision Diagnosis and Prognosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Wang, Q.; Ma, J.; Zeng, Y.E. Hypoxia-induced reactive oxygen species in organ and tissue fibrosis. Biocell 2023, 47, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Chen, C.; Yang, S.; Lin, M.; Long, J.; Yao, J.; Lin, Y.; Yi, F.; et al. Targeting oxidative stress as a preventive and therapeutic approach for cardiovascular disease. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, H.; Du, F.; Zeng, X.; Guo, C. Nrf2 for a key member of redox regulation: A novel insight against myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injuries. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Xiao, J.H. The Keap1-Nrf2 System: A Mediator between Oxidative Stress and Aging. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6635460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaiahgari, S.; Yerrapureddy, A.; Hassoun, P.M.; Garcia, J.G.; Birukov, K.G.; Reddy, S.P. EGFR-activated signaling and actin remodeling regulate cyclic stretch-induced NRF2-ARE activation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2007, 36, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niture, S.K.; Jaiswal, A.K. Nrf2 protein up-regulates antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 and prevents cellular apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 9873–9886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, T.; Hallis, S.P.; Kwak, M.K. Hypoxia, oxidative stress, and the interplay of HIFs and NRF2 signaling in cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, P.; Zhong, J.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; Chen, C. HIF-1alpha in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Shang, P.; Li, D. Luteolin: A Flavonoid that Has Multiple Cardio-Protective Effects and Its Molecular Mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Liu, A.; Li, L.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X. Robinin decreases myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via Nrf2 anti-oxidative effects mediated by Akt/GSK3beta/Fyn in hypercholesterolemic rats. J. Mol. Histol. 2025, 56, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, J.; Kang, P.; Shi, C.; Qian, S. Quercetin Inhibits Pyroptosis in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy through the Nrf2 Pathway. J. Diabetes Res. 2022, 2022, 9723632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou-Siafis, S.K.; Tsiftsoglou, A.S. The Key Role of GSH in Keeping the Redox Balance in Mammalian Cells: Mechanisms and Significance of GSH in Detoxification via Formation of Conjugates. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Ru, X.; Wen, T. NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ajam, A.; Huang, J.; Yeh, Y.S.; Razani, B. Glutamine-glutamate imbalance in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 3, 1377–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitzer, L. Biosynthesis of Glutamate, Aspartate, Asparagine, L-Alanine, and D-Alanine. EcoSal Plus 2004, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, P.; Xiao, D.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, W.; Ding, L.; Dong, H.; Wei, C.; et al. Paeoniflorin alleviates AngII-induced cardiac hypertrophy in H9c2 cells by regulating oxidative stress and Nrf2 signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Kan, C.; Zhang, K.; Sheng, S.; Qiu, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hou, N.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X. Glycerophospholipid and Sphingosine-1-phosphate Metabolism in Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2025, 18, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Lei, H.; Cai, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhu, P.; He, Q.; Zhao, M. The Nrf-2/HO-1 Signaling Axis: A Ray of Hope in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2020, 5695723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N.K.; Fitzgerald, H.K.; Dunne, A. Regulation of inflammation by the antioxidant haem oxygenase 1. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Du, J.; Shi, H.; Wang, S.; Yan, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, Z.; Mu, Y.; Qian, C.; et al. Adiponectin suppresses tumor growth of nasopharyngeal carcinoma through activating AMPK signaling pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Compounds | Formula | mz |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eriodictyol 7-rhamnoside | C21H22O10 | 433.11 |

| 2 | Luteolin 6-C-glucoside 8-C-arabinoside | C27H30O16 | 609.16 |

| 3 | Quercetin 3-O-malonylglucoside | C24H22O15 | 551.1 |

| 4 | Kaempferol 3-glucuronide | C21H18O12 | 461.08 |

| 5 | Rutin | C27H30O16 | 609.16 |

| 6 | quercetin 3-O-glucuronide | C21H18O13 | 479.08 |

| 7 | Eriodictyol | C15H12O6 | 289.07 |

| 8 | quercetin | C15H10O7 | 303.05 |

| 9 | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside | C21H21O11 | 450.11 |

| 10 | Luteolin 7-glucoside | C21H20O11 | 447.1 |

| 11 | Quercetin 3-(6′′-malonyl-glucoside) | C24H22O15 | 551.1 |

| 12 | Diosmetin-7-O-rutinoside | C28H32O15 | 609.17 |

| 13 | Diosmetin | C16H12O6 | 301.07 |

| 14 | Isorhamnetin | C16H12O7 | 317.07 |

| 15 | Apigenin | C15H10O5 | 269.05 |

| 16 | Linarin | C28H32O14 | 593.18 |

| 17 | Luteolin | C15H10O6 | 287.05 |

| 18 | Acacetin | C16H12O5 | 285.07 |

| 19 | Wogonoside | C22H20O11 | 461.11 |

| 20 | D-Phenylalanine | C9H11NO2 | 166.08504 |

| 21 | Tricin | C17H14O7 | 331.08014 |

| 22 | Pachypodol | C18H16O8 | 361.0894 |

| 23 | Nerolidol | C15H26O | 205.19019 |

| 24 | Artemitin | C20H20O8 | 389.1181 |

| 25 | Parthenolide | C15H20O3 | 231.13742 |

| 26 | Phthalic acid | C8H6O4 | 149.02257 |

| 27 | Quinic acid | C7H12O6 | 191.05876 |

| 28 | 5-Caffeoylquinic acid | C16H18O9 | 353.09726 |

| 29 | Spiraeoside | C21H20O12 | 301.03964 |

| 30 | 5,7,3′,4′-Tetrahydroxy-6,8-dimethoxyflavone | C17H14O8 | 345.06622 |

| 31 | Idoxanthin | C40H54O4 | 597.37714 |

| 32 | Skullcapflavone II | C19H18O8 | 373.0985 |

| Pathway Name | p | −log (p) | FDR | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 0.0018256 | 6.3059 | 0.14787 | 0.12245 |

| Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis | 0.0080153 | 4.8264 | 0.23773 | 1 |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 0.011065 | 4.5039 | 0.23773 | 0.18802 |

| Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 0.013826 | 4.2812 | 0.23773 | 0.63637 |

| Glutathione metabolism | 0.014675 | 4.2216 | 0.23773 | 0.04007 |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.024055 | 3.7274 | 0.32475 | 0.17407 |

| Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | 0.042584 | 3.1563 | 0.43117 | 0.4 |

| Phenylalanine metabolism | 0.042584 | 3.1563 | 0.43117 | 0.40741 |

| Ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis | 0.10925 | 2.2141 | 0.98326 | 0 |

| beta-Alanine metabolism | 0.15942 | 1.8362 | 1 | 0.22222 |

| Compound | Molecule Formula | Compound | Molecule Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acacetin | C16H12O5 | Eriodictyol | C15H12O6 |

| Apigenin | C15H10O5 | Luteolin | C15H10O6 |

| Acacipetalin | C11H17NO6 | Quercetin | C15H10O7 |

| Artemetin | C20H20O8 | Spinacetin | C17H14O8 |

| Axillarin | C17H14O8 | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 |

| Cirsiliol | C17H14O7 | Chryseriol | C16H12O6 |

| Chrysosplenol D | C18H16O8 | Naringenin | C15H12O5 |

| Diosmetin | C16H12O6 | Isorhamnetin | C16H12O7 |

| Eupatilin | C18H16O7 | Eupatorin | C18H16O7 |

| Compound | Gene | Binding Energy/kcal/mol | Compound | Gene | Binding Energy/kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacetin | PTGS2 | −9.30 | Luteolin | PTGS2 | −9.50 |

| AKT1 | −9.40 | AKT1 | −7.20 | ||

| EGFR | −9.10 | EGFR | −8.90 | ||

| GAPDH | −8.40 | GAPDH | −8.90 | ||

| BCL2 | −7.20 | BCL2 | −7.30 | ||

| Naringenin | PTGS2 | −9.30 | Apigenin | PTGS2 | −9.00 |

| AKT1 | −7.10 | AKT1 | −7.20 | ||

| EGFR | −8.90 | EGFR | −8.90 | ||

| GAPDH | −9.00 | GAPDH | −9.00 | ||

| BCL2 | −7.00 | BCL2 | −7.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shi, G.; Meng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Yu, H. Network Pharmacology and Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis of the Protective Mechanisms of Total Flavonoids from Chuju in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010068

Shi G, Meng H, Zhang Z, Zhang G, Li Y, Yu H. Network Pharmacology and Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis of the Protective Mechanisms of Total Flavonoids from Chuju in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Gaocheng, Huihui Meng, Zongmeng Zhang, Guanglei Zhang, Yanran Li, and Hao Yu. 2026. "Network Pharmacology and Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis of the Protective Mechanisms of Total Flavonoids from Chuju in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010068

APA StyleShi, G., Meng, H., Zhang, Z., Zhang, G., Li, Y., & Yu, H. (2026). Network Pharmacology and Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis of the Protective Mechanisms of Total Flavonoids from Chuju in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010068