Salmonellosis as a One Health–One Biofilm Challenge: Biofilm Formation by Salmonella and Alternative Eradication Strategies in the Post-Antibiotic Era

Abstract

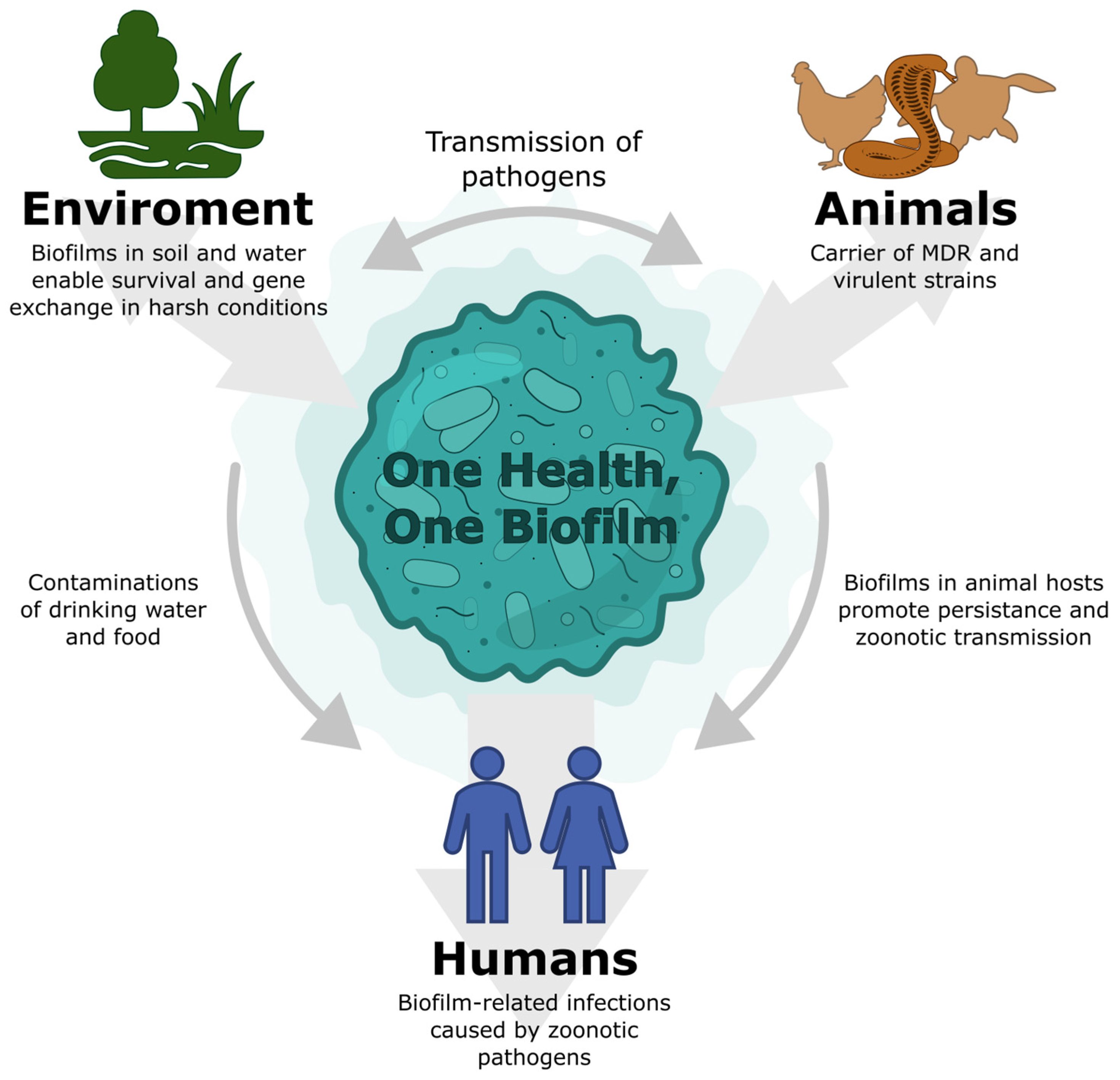

1. Introduction

2. Salmonella as a Zoonotic Pathogen

2.1. Salmonellosis

2.2. Reptile-Associated Salmonellosis

2.3. Drug Resistance in Salmonella enterica

2.4. Salmonella Virulence Factors

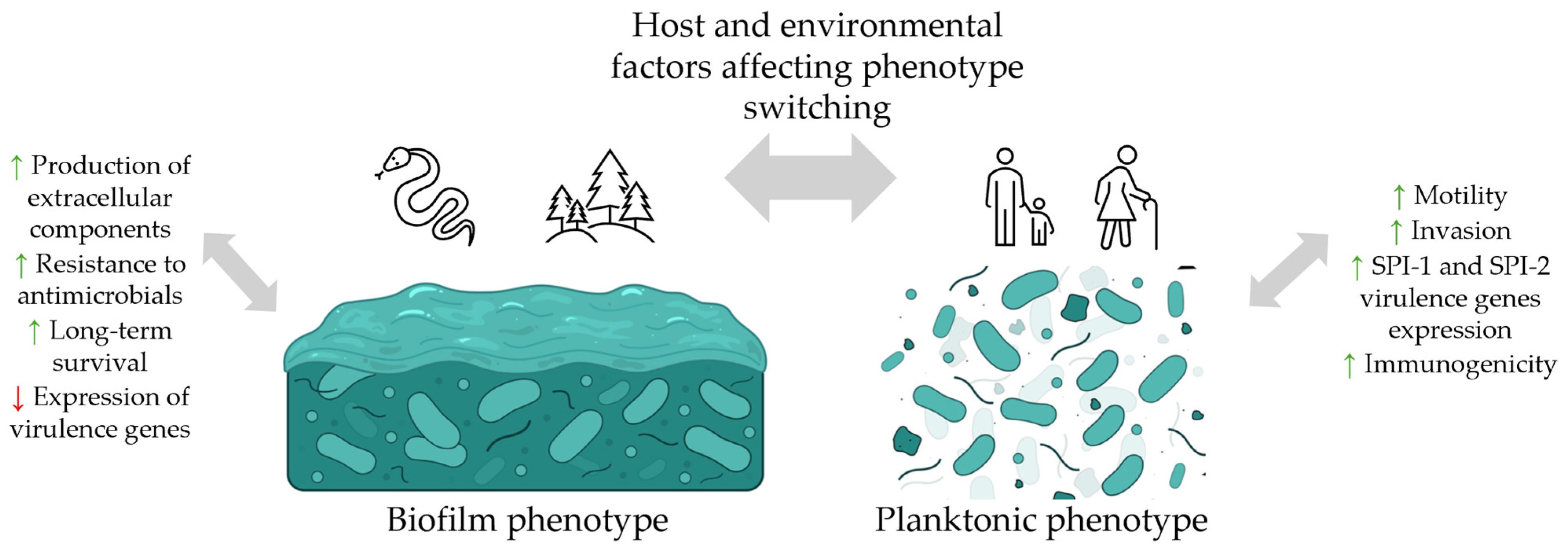

3. Biofilm Formation by Salmonella

3.1. Regulation of the Biofilm Development

3.2. Biofilm Metrix Composition

3.3. Experimental Techniques to Study Biofilm of Salmonella

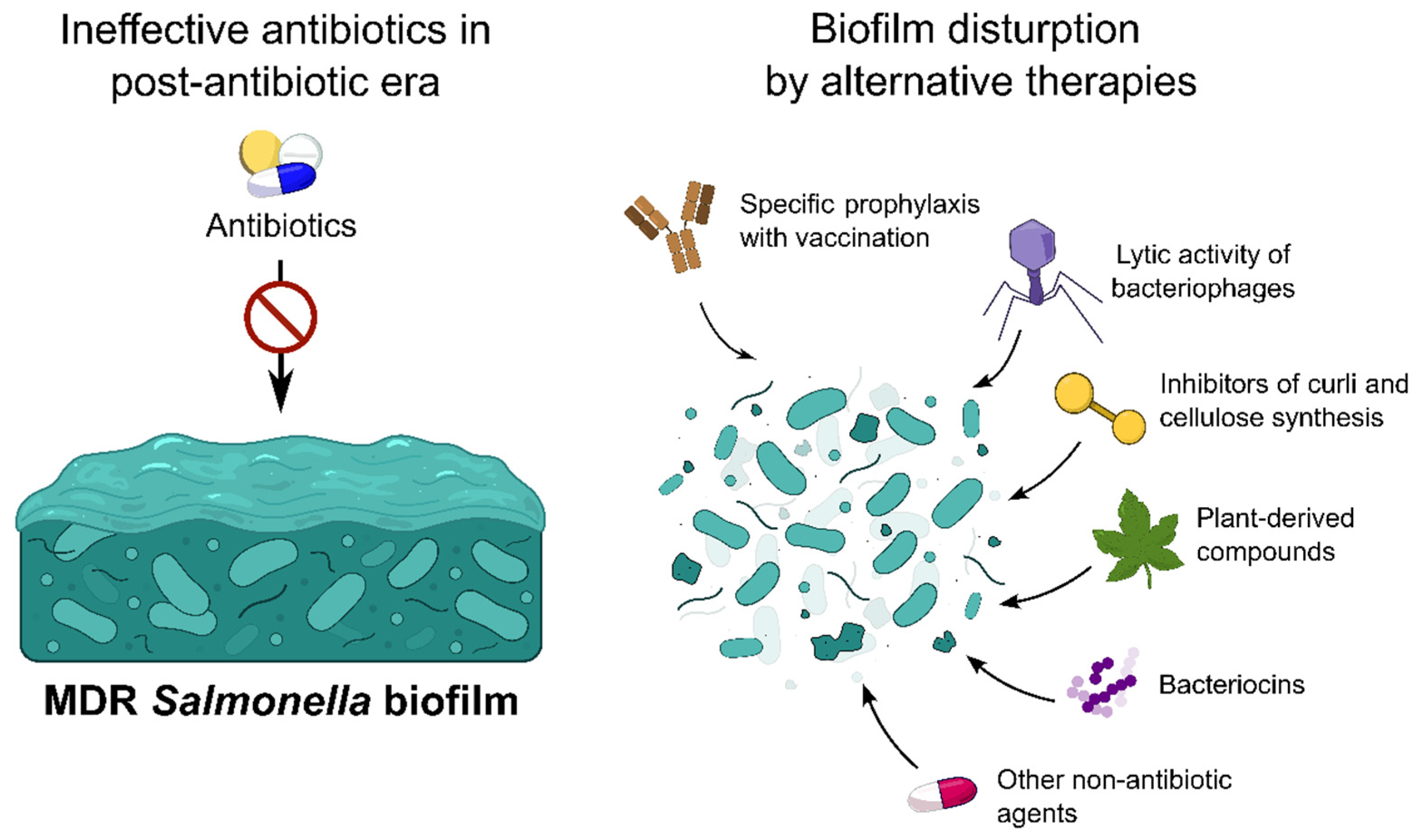

4. Methods for the Salmonella Biofilm Prevention and Eradication

4.1. Vaccination

4.2. Bacteriophages

| Phage | Activity | Serovar | Experimental Model | Parametrical Changes | EOP * | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lysSEP21 | Lytic | S. Enteritidis S. Typhimurium | In vitro and food ex vivo model | Biomass ↓ (≤60% in 5 h; in vitro) Viability ↓ (6–9 log10 in 5 h; in vitro) Viability ↓ (≤3 log10 CFU/mL in 9 days; in vivo) | ns | [130] |

| UPWr_S134 phage | Lytic | S. Enteritidis | In vitro and animal in vivo model | Biomass ↓ (≤54% in 4 h; in vitro) Viability ↓ (1–2 log10 CFU/mL in 9 days; in vivo) Biomass ↓ (≈60% in 24 h; in vitro) | ns | [128] |

| phage X5 | Lytic | S. Pullorum | In vitro and food ex vivo model | Viability ↓ (1.5 log10 CFU/mL in 24 h; in vitro) Viability ↓ (1–2.5 log10 CFU/mL in 24 h; ex vivo) | ns | [131] |

| KE04, KE06, KE15, KE17, KE26, KE24, KE23 | Lytic | S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis | In vitro | Biomass ↓ (≤70% in 24 h) | ≤3 | [132] |

| P22 | Lytic | S. Typhimurium | In vitro | Biomass ↓ (≤80% in 24 h) | ns | [129] |

| Epseptimavirus MSP1 phage | Lytic | S. Thompson | In vitro and food ex vivo model | Biomass ↓ (≤46.4% in 12 h; in vitro) Viability ↓ (≤3.5 log10 CFU/mL in 4 h; in vitro) Viability ↓ (≤5 log10 CFU/mL in 3–12 h; ex vivo) | 0.1–1 | [124] |

| UPF_BP1 and UPF_BP2 phages | Lytic | S. Gallinarum | In vitro | Activity against 78% of biofilm forming isolates and against 77% of MDR strains | ns | [122] |

| Jerseyvirus 4FS1 phage | Lytic and ECM depolymerization | S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, S. Abortusequi | In vitro | Biomass ↓ (≤75% in 2 h) | ≤1 | [127] |

| Agtrevirus phages | Lytic | S. Blockley | In vitro and animal ex vivo model | Biomass ↓ (≤35% in 48 h; in vitro) Viability ↓ (≤3 log10 CFU/mL in 48 h; in vitro) Viability ↓ (≤2.5 log10 CFU/mL in 48 h; ex vivo) | 1 | [126] |

| Phage cocktails | ||||||

| 4 phages cocktail | Lytic | S. enterica (I) | In vitro | Strain-dependent biomass ↓ (10–100% in 24 h; in vitro) | ≤1 for single phages | [134] |

| 3 phages cocktail | Lytic and ECM depolymerization | S. Infantis | In vitro | Condition-dependent viability ↓ (mostly 3–4 log10 CFU/mL in 4–8 h) | 1–1.46 | [84] |

| 3 phages cocktail | Lytic | S. Heidelberg | In vitro | Strain-dependent viability ↓ (≤90% in 7 days) | ns | [135] |

| 5 phages cocktail | Lytic | S. Typhimurium | In vitro | Biomass ↓ (≤63.6% in 24 h) | ns | [136] |

4.3. Plant-Based Compounds

4.4. Microbial and Host Peptides

4.5. Fatty Acids

4.6. Synthetic and Semi-Synthetic Compounds

| Category | Substance | Strain | Effect | Antimicrobial Values | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant-based compounds | Cinnamon essential oil | S. Thompson | Disrupting biofilm integrity | 0.62 μL/mL | [160] |

| Cinnamon star anise essential oil | 25 μL/mL | ||||

| Clove oil, Eugenol | EHEC model | Inhibition of curli fimbriae production | 0.005% | [140] | |

| Nano-garlic emulsion | S. Typhimurium, S. Infantis, S. Kentucky, S. Molade | Inhibition of biofilm formation by downregulating csg genes | 12.5–25 μg/mL | [141] | |

| Diosmin | S. Typhimurium | Reduction in biofilm formation | 0.5–2 mg/mL; | [142] | |

| Frulic acid | S. Enteritidis | Inhibition of motility, biofilm biomass, and EPS production | 1.0 mg/mL | [143] | |

| P-coumaric acid | 0.25–0.5 mg/mL | [143] | |||

| Antimicrobial peptides | Enterocin AS-48 (Enterococcus) | Salmonella spp. | Reduction in biofilm and cell grown inhibition | Synergism with antimicrobials; 25–50 mg/L | [147] |

| DF01 (Lactobacillus) | S. Typhimurium | Inhibition of biofilm production | ns | [161] | |

| K10, HW01 (Pediococcus) | Reduction in biofilm on stainless steel and in meat | 1.0 mg/mL | [162] | ||

| Bovine lactoferrin and lactoferrin-derived peptides | Reduction in biofilm | 1 ≥ 10 µM | [148] | ||

| Fatty Acids | Caproic acid, Acetic acid, Isobutyric acid, Valeric acid and others | S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis | Eradication of biofilm and planktonic cells | Dependent of compound tested | [151] |

| Propionate and Butyrate | S. Typhimurium | Eradication of biofilm | 2 mg/mL | [152] | |

| Caprylic acid nano-emulsion | S. Enteritidis | ≤0.4% | [153] | ||

| Synthetic and semi-synthetic compounds | FN075, BibC6 | E. coli model | Attenuated virulence in a mouse model of urinary tract infection with UPEC model | ≥1.0 mM | [156] |

| Modified ring-fused 2-pyridone | Inhibition of csgA gene and curli production in vitro | 50 mM | [157] | ||

| Plasma treated water | S. Typhimurium | Reduction in biofilm | 25% | [158] |

4.7. Limitations of Alternative Methods Fighting Against Salmonella Biofilms

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rahman, M.T.; Sobur, M.A.; Islam, M.S.; Ievy, S.; Hossain, M.J.; El Zowalaty, M.E.; Rahman, A.T.; Ashour, H.M. Zoonotic Diseases: Etiology, Impact, and Control. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Faramarzi, A.; Norouzi, S.; Dehdarirad, H.; Aghlmand, S.; Yusefzadeh, H.; Javan-Noughabi, J. The global economic burden of COVID-19 disease: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About Zoonotic Diseases [Internet]; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/about/about-zoonotic-diseases.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 and Antimicrobial Resistance. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 12 July 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/data-research/threats/COVID-19.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Couto, R.M.; Brandespim, D.F. A Review of the One Health Concept and Its Application as a Tool for Policy-Makers. Int. J. One Health 2020, 6, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Calva, E.; Maloy, S. One Health and Food-Borne Disease: Salmonella Transmission between Humans, Animals, and Plants. Microbiol. Spectr. 2014, 2, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, S.A.; Collignon, P.J. Antimicrobial Resistance: A One Health Perspective. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zinsstag, J.; Crump, L.; Schelling, E.; Hattendorf, J.; Maidane, Y.O.; Ali, K.O.; Muhummed, A.; Umer, A.A.; Aliyi, F.; Nooh, F.; et al. Climate change and One Health. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365, fny085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jacques, M.; Malouin, F. One Health-One Biofilm. Vet. Res. 2022, 53, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Issenhuth-Jeanjean, S.; Roggentin, P.; Mikoleit, M.; Guibourdenche, M.; de Pinna, E.; Nair, S.; Fields, P.I.; Weill, F.X. Supplement 2008–2010 (no. 48) to the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme. Res. Microbiol. 2014, 165, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimont, A.; Weill, F. Antigenic Formulae of the Salmonella Serovars, 9th ed.; Institute Pasteur: World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Reference and Research on Salmonella: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, B.; Książczyk, M.; Krzyżewska, E.; Rogala, K.; Kuczkowski, M.; Woźniak-Biel, A.; Korzekwa, K.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Ratajszczak, R.; Wieliczko, A.; et al. Comparison of the phylogenetic analysis of PFGE profiles and the characteristic of virulence genes in clinical and reptile associated Salmonella strains. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland, A.M.; Sandvik, L.M.; Skarstein, M.M.; Svendal, L.; Debenham, J.J. Prevalence of Salmonella serovars isolated from reptiles in Norwegian zoos. Acta Vet. Scand. 2020, 62, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając, M.; Wasyl, D.; Różycki, M.; Bilska-Zając, E.; Fafiński, Z.; Iwaniak, W.; Krajewska, M.; Hoszowski, A.; Konieczna, O.; Fafińska, P.; et al. Free-living snakes as a source and possible vector of Salmonella spp. and parasites. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2016, 62, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prud’homme, Y.; Burton, F.J.; McClave, C.; Calle, P.P. Prevalence, incidence and identification of Salmonella enterica from wild and captive grand cayman iguanas (Cyclura lewisi). J. Zoo. Wildl. Med. 2018, 49, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dróżdż, M.; Małaszczuk, M.; Paluch, E.; Pawlak, A. Zoonotic potential and prevalence of Salmonella serovars isolated from pets. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2021, 11, 1975530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoffmann, S.; White, A.E.; McQueen, R.B.; Ahn, J.W.; Gunn-Sandell, L.B.; Scallan Walter, E.J. Economic Burden of Foodborne Illnesses Acquired in the United States. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2025, 22, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarino, A.; Ashenazi, S.; Gendrel, D.; Lo Vecchio, A.; Shamir, R.; Szajewska, H. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe: Update 2014. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 59, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- EFSA and ECDC (European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). The European Union One Health 2020 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2021, 19, 6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaji, S.; Selvaraj, R.K.; Shanmugasundaram, R. Salmonella Infection in Poultry: A Review on the Pathogen and Control Strategies. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, L.; Procura, F.; Trejo, F.M.; Bueno, D.J.; Golowczyc, M.A. Biofilm Formation by Salmonella sp. in the Poultry Industry: Detection, Control and Eradication Strategies. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, L.; Buuck, S.; Eisenstein, T.; Cote, A.; McCormic, Z.D.; Kremer-Caldwell, S.; Kissler, B.; Forstner, M.; Sorenson, A.; Wise, M.E.; et al. Salmonella Outbreaks Associated with Not Ready-to-Eat Breaded, Stuffed Chicken Products—United States, 1998–2022. MMWR-Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stilz, C.R.; Cavallo, S.; Garman, K.; Dunn, J.R. Salmonella Enteritidis Outbreaks Associated with Egg-Producing Farms Not Regulated by Food and Drug Administration’s Egg Safety Rule. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2022, 19, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermudez-Aguirre, D.; Carter, J.; Niemira, B.A. An Investigation About the Historic Global Foodborne Outbreaks of Salmonella spp. in Eggs: From Hatcheries to Tables. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lowther, S.A.; Medus, C.; Scheftel, J.; Leano, F.; Jawahir, S.; Smith, K. Foodborne Outbreak of Salmonella Subspecies IV Infections Associated with Contamination from Bearded Dragons. Zoonoses Public Health 2011, 58, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, L.; Vercammen, F.; Bertrand, S.; Collard, J.M.; De Ceuster, S. Isolation of Salmonella from environmental samples collected in the reptile department of Antwerp Zoo using different selective methods. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 101, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otake, S.; Ajiki, J.; Yoshida, M.; Koriyama, T.; Kasai, M. Contact with a snake leading to testicular necrosis due to Salmonella Saintpaul infection. Pediatr. Int. 2021, 63, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasu, Y.; Kawago, Y. A case of testicular seminoma with testicular abscess caused by Salmonella saintpaul. Int. Cancer Conf. J. 2023, 12, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bruning, A.H.; Beld, M.V.; Laverge, J.; Welkers, M.R.A.; Kuil, S.D.; Bruisten, S.M.; van Dam, A.P.; Stam, A.J. Reptile-associated Salmonella urinary tract infection: A case report. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 105, 115889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paphitis, K.; Habrun, C.A.; Stapleton, G.S.; Reid, A.; Lee, C.; Majury, A.; Murphy, A.; McClinchey, H.; Corbeil, A.; Kearney, A.; et al. Salmonella Vitkin Outbreak Associated with Bearded Dragons, Canada and United States, 2020-2022. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Olariu, A.; Jain, S.; Gupta, A.K. Salmonella kingabwa meningitis in a neonate. BMJ Case Rep. 2012, 2012, bcr1020115032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mahajan, R.K.; Khan, S.A.; Chandel, D.S.; Kumar, N.; Hans, C.; Chaudhry, R. Fatal case of Salmonella enterica subsp. arizonae gastroenteritis in an infant with microcephaly. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 5830–5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schneider, L.; Ehlinger, M.; Stanchina, C.; Giacomelli, M.C.; Gicquel, P.; Karger, C.; Clavert, J.M. Salmonella enterica subsp. arizonae bone and joints sepsis. A case report and literature review. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2009, 95, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavrilovici, C.; Pânzaru, C.V.; Cozma, S.; Mârţu, C.; Lupu, V.V.; Ignat, A.; Miron, I.; Stârcea, M. Message from a turtle”: Otitis with Salmonella arizonae in children: Case report. Medicine 2017, 96, e8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Di Bella, S.; Capone, A.; Bordi, E.; Johnson, E.; Musso, M.; Topino, S.; Noto, P.; Petrosillo, N. Salmonella enterica ssp. arizonae infection in a 43-year-old Italian man with hypoglobulinemia: A case report and review of the literature. J. Med. Case Rep. 2011, 5, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kelly, J.; Hopkin, R.; Rimsza, M.E. Rattlesnake meat ingestion and Salmonella arizona infection in children: Case report and review of the literature. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1995, 14, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, A.; Małaszczuk, M.; Dróżdż, M.; Bury, S.; Kuczkowski, M.; Morka, K.; Cieniuch, G.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Wzorek, A.; Korzekwa, K.; et al. Virulence factors of Salmonella spp. isolated from free-living grass snakes Natrix natrix. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 16, e13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mokracka, J.; Krzymińska, S.; Ałtunin, D.; Wasyl, D.; Koczura, R.; Dudek, K.; Dudek, M.; Chyleńska, Z.A.; Ekner-Grzyb, A. In vitro virulence characteristics of rare serovars of Salmonella enterica isolated from sand lizards (Lacerta agilis L.). Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2018, 111, 1863–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McWhorter, A.; Owens, J.; Valcanis, M.; Olds, L.; Myers, C.; Smith, I.; Trott, D.; McLelland, D. In vitro invasiveness and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella enterica subspecies isolated from wild and captive reptiles. Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dégi, J.; Herman, V.; Radulov, I.; Morariu, F.; Florea, T.; Imre, K. Surveys on Pet-Reptile-Associated Multi-Drug-Resistant Salmonella spp. in the Timișoara Metropolitan Region-Western Romania. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Petano-Duque, J.M.; Rueda-García, V.; Rondón-Barragán, I.S. Virulence genes identification in Salmonella enterica isolates from humans, crocodiles, and poultry farms from two regions in Colombia. Vet. World 2023, 16, 2096–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chaudhari, R.; Singh, K.; Kodgire, P. Biochemical and molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Salmonella spp. Res. Microbiol. 2023, 174, 103985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Liao, X.P.; Liu, Y.H.; Sun, J. Efflux Pump Overexpression Contributes to Tigecycline Heteroresistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Sun, F.; Sun, D.; Wang, Z.; Jin, S.; Pan, Z.; Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Jiao, X. Multidrug resistance and prevalence of quinolone resistance genes of Salmonella enterica serotypes 4,[5],12:i:- in China. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 330, 108692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung The, H.; Pham, P.; Ha Thanh, T.; Phuong, L.V.K.; Yen, N.P.; Le, S.H.; Vu Thuy, D.; Chau, T.T.H.; Le Phuc, H.; Ngoc, N.M.; et al. Multidrug resistance plasmids underlie clonal expansions and international spread of Salmonella enterica serotype 1,4,[5],12:i:- ST34 in Southeast Asia. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mokgophi, T.M.; Gcebe, N.; Fasina, F.; Adesiyun, A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Salmonella Isolates on Chickens Processed and Retailed at Outlets of the Informal Market in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Pathogens 2021, 10, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, G.; Tang, W.; Song, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Zou, M. Antimicrobial resistance and genomic characteristics of Salmonella from broilers in Shandong Province. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1292401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ćwiek, K.; Korzekwa, K.; Tabiś, A.; Bania, J.; Bugla-Płoskońska, G.; Wieliczko, A. Antimicrobial Resistance and Biofilm Formation Capacity of Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis Strains Isolated from Poultry and Humans in Poland. Pathogens 2020, 9, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parvin, M.S.; Hasan, M.M.; Ali, M.Y.; Chowdhury, E.H.; Rahman, M.T.; Islam, M.T. Prevalence and Multidrug Resistance Pattern of Salmonella Carrying Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase in Frozen Chicken Meat in Bangladesh. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 2107–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holohan, N.; Wallat, M.; Hai Yen Luu, T.; Clark, E.; Truong, D.T.Q.; Xuan, S.D.; Vu, H.T.K.; Van Truong, D.; Tran Huy, H.; Nguyen-Viet, H.; et al. Analysis of Antimicrobial Resistance in Non-typhoidal Salmonella Collected from Pork Retail Outlets and Slaughterhouses in Vietnam Using Whole Genome Sequencing. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 816279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- González-Santamarina, B.; García-Soto, S.; Dang-Xuan, S.; Abdel-Glil, M.Y.; Meemken, D.; Fries, R.; Tomaso, H. Genomic Characterization of Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella Serovars Derby and Rissen from the Pig Value Chain in Vietnam. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 705044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naser, J.A.; Hossain, H.; Chowdhury, M.S.; Liza, N.A.; Lasker, R.M.; Rahman, A.; Haque, M.A.; Hossain, M.M.; Rahman, M.M. Exploring of spectrum beta lactamase producing multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovars in goat meat markets of Bangladesh. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2024, 25, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, W.; Xu, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, M.; Liang, J.; Wei, P. Investigation of biofilm formation and the associated genes in multidrug-resistant Salmonella pullorum in China (2018–2022). Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1248584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Manafi, L.; Aliakbarlu, J.; Dastmalchi Saei, H. Antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation ability of Salmonella serotypes isolated from beef, mutton, and meat contact surfaces at retail. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 2516–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xue, C.; Yan, J.; Li, X.; Zheng, X.; Dong, R.; Bai, J.; Su, Y.; et al. Analysis of antibiotic-induced drug resistance of Salmonella enteritidis and its biofilm formation mechanism. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 10254–10263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, P.; Song, X.; Zhang, H.; Ma, S.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Lv, R.; Liu, X.; Ma, S.; et al. Salmonella Typhimurium reprograms macrophage metabolism via T3SS effector SopE2 to promote intracellular replication and virulence. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pico-Rodríguez, J.T.; Martínez-Jarquín, H.; Gómez-Chávez, J.; Juárez-Ramírez, M.; Martínez-Chavarría, L.C. Effect of Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 and 2 (SPI-1 and SPI-2) deletion on intestinal colonization and systemic dissemination in chickens. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerny, O.; Holden, D.W. Salmonella SPI-2 type III secretion system-dependent inhibition of antigen presentation and T cell function. Immunol. Lett. 2019, 215, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, D.O.; Horstmann, J.A.; Giralt-Zúñiga, M.; Weber, W.; Kaganovitch, E.; Durairaj, A.C.; Klotzsch, E.; Strowig, T.; Erhardt, M. SPI-1 virulence gene expression modulates motility of Salmonella Typhimurium in a proton motive force- and adhesins-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eade, C.R.; Bogomolnaya, L.; Hung, C.C.; Betteken, M.I.; Adams, L.G.; Andrews-Polymenis, H.; Altier, C. Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 1 Is Expressed in the Chicken Intestine and Promotes Bacterial Proliferation. Infect. Immun. 2018, 87, e00503-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Figueira, R.; Holden, D.W. Functions of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2) type III secretion system effectors. Microbiology 2012, 158, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sia, C.M.; Pearson, J.S.; Howden, B.P.; Williamson, D.A.; Ingle, D.J. Salmonella pathogenicity islands in the genomic era. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, M.E.; Quick, L.N.; Ubol, N.; Shrom, S.; Dollahon, N.; Wilson, J.W. Characterization of Salmonella type III secretion hyper-activity which results in biofilm-like cell aggregation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giaouris, E.D.; Nychas, G.J. The adherence of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 to stainless steel: The importance of the air-liquid interface and nutrient availability. Food Microbiol. 2006, 23, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz-Méndez, A.M.; Lamas, A.; Vázquez, B.; Miranda, J.M.; Cepeda, A.; Franco, C.M. Effect of Food Residues in Biofilm Formation on Stainless Steel and Polystyrene Surfaces by Salmonella enterica Strains Isolated from Poultry Houses. Foods 2017, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hurrell, E.; Kucerova, E.; Loughlin, M.; Caubilla-Barron, J.; Forsythe, S.J. Biofilm formation on enteral feeding tubes by Cronobacter sakazakii, Salmonella serovars and other Enterobacteriaceae. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 136, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sholpan, A.; Lamas, A.; Cepeda, A.; Franco, C.M. Salmonella spp. Quorum Sensing: An Overview from Environmental Persistence to Host Cell Invasion. AIMS Microbiol. 2021, 7, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, K.; Nayak, S.R.; Bihary, A.; Sahoo, A.K.; Mohanty, K.C.; Palo, S.K.; Sahoo, D.; Pati, S.; Dash, P. Association of Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation with Salmonella Virulence: Story Beyond Gathering and Cross-Talk. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 5887–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karygianni, L.; Ren, Z.; Koo, H.; Thurnheer, T. Biofilm Matrixome: Extracellular Components in Structured Microbial Communities. Trends Microbiol. 2020, 28, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, B.; Ding, X.; Bin, P.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, G. Regulatory Mechanisms between Quorum Sensing and Virulence in Salmonella. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cai, Z.; Shao, X.; Zhang, W.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, C.; Schuster, S.C.; Yang, L.; Deng, X. Pleiotropic Effects of c-di-GMP Content in Pseudomonas syringae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e00152-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römling, U.; Bian, Z.; Hammar, M.; Sierralta, W.D.; Normark, S. Curli fibers are highly conserved between Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli with respect to operon structure and regulation. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tükel, C.; Raffatellu, M.; Humphries, A.D.; Wilson, R.P.; Andrews-Polymenis, H.L.; Gull, T.; Figueiredo, J.F.; Wong, M.H.; Michelsen, K.S.; Akçelik, M.; et al. CsgA is a pathogen-associated molecular pattern of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium that is recognized by Toll-like receptor 2. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 58, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhoite, S.; van Gerven, N.; Chapman, M.R.; Remaut, H. Curli Biogenesis: Bacterial Amyloid Assembly by the Type VIII Secretion Pathway. EcoSal Plus 2019, 8, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Latasa, C.; Echeverz, M.; García, B.; García-Ona, E.; Burgui, S.; Casares, N.; Hervás-Stubbs, S.; Lasarte, J.J.; Lasa, I.; Solano, C.; et al. Evaluation of a Salmonella Strain Lacking the Secondary Messenger C-di-GMP and RpoS as a Live Oral Vaccine. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jonas, K.; Tomenius, H.; Kader, A.; Normark, S.; Römling, U.; Belova, L.M.; Melefors, O. Roles of curli, cellulose and BapA in Salmonella biofilm morphology studied by atomic force microscopy. BMC Microbiol. 2007, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Römling, U.; Galperin, M.Y.; Gomelsky, M. Cyclic di-GMP: The first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Echarren, M.L.; Figueroa, N.R.; Vitor-Horen, L.; Pucciarelli, M.G.; García-Del Portillo, F.; Soncini, F.C. Balance between bacterial extracellular matrix production and intramacrophage proliferation by a Salmonella-specific SPI-2-encoded transcription factor. Mol. Microbiol. 2021, 116, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, M.H.; Lee, E.J.; Choi, J.; Groisman, E.A. Salmonella promotes virulence by repressing cellulose production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5183–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Römling, U. Characterization of the rdar morphotype, a multicellular behaviour in Enterobacteriaceae. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Torres-Boncompte, J.; Sanz-Zapata, M.; Garcia-Llorens, J.; Soriano, J.M.; Catalá-Gregori, P.; Sevilla-Navarro, S. In Vitro Insights into the Anti-Biofilm Potential of Salmonella Infantis Phages. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Musa, L.; Toppi, V.; Stefanetti, V.; Spata, N.; Rapi, M.C.; Grilli, G.; Addis, M.F.; Di Giacinto, G.; Franciosini, M.P.; Casagrande Proietti, P. High Biofilm-Forming Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella Infantis Strains from the Poultry Production Chain. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tulin, G.; Méndez, A.A.; Figueroa, N.R.; Smith, C.; Folmer, M.P.; Serra, D.; Wade, J.T.; Checa, S.K.; Soncini, F.C. Integration of BrfS into the biofilm-controlling cascade promotes sessile Salmonella growth at low temperatures. Biofilm 2025, 9, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Futoma-Kołoch, B.; Małaszczuk, M.; Korzekwa, K.; Steczkiewicz, M.; Gamian, A.; Bugla-Płoskońska, G. The Prolonged Treatment of Salmonella enterica Strains with Human Serum Effects in Phenotype Related to Virulence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Azeredo, J.; Azevedo, N.F.; Briandet, R.; Cerca, N.; Coenye, T.; Costa, A.R.; Desvaux, M.; Di Bonaventura, G.; Hébraud, M.; Jaglic, Z.; et al. Critical Review on Biofilm Methods. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 43, 313–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleaver, L.; Garnett, J.A. How to Study Biofilms: Technological Advancements in Clinical Biofilm Research. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1335389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Khan, S.A.; Walsh, L.J.; Ziora, Z.M.; Seneviratne, C.J. Classical and Modern Models for Biofilm Studies: A Comprehensive Review. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, D.; Liu, Z.; Dong, X.; Yan, S.; Zhu, L.; Cui, D.; Chen, L.; et al. Biofilm-Forming Ability of Salmonella enterica Strains of Different Serotypes Isolated from Multiple Sources in China. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 182, 106275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereno, M.; Ziech, R.; Druziani, J.; Pereira, J.; Bersot, L.d.S. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Biofilm Production by Salmonella spp. Strains Isolated from Frozen Poultry Carcasses. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Avic. 2017, 19, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiger, M.R.; González, J.F.; Gonzalez-Escobedo, G.; Kuck, H.; White, P.; Gunn, J.S. Pathoadaptive Alteration of Salmonella Biofilm Formation in Response to the Gallbladder Environment. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00774-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahıla, F.; Yaşa, İ.; Yalçın, H.T. Biofilm Formation by Salmonella enterica Strains. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivana, Č.; Marija, Š.; Jovanka, L.; Bojana, K.; Nevena, B.; Dubravka, M.; Ljiljana, S. Biofilm Forming Ability of Salmonella Enteritidis In Vitro. Acta Vet. 2015, 65, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Pal, D.; Kumar, A. Interrogating Salmonella Typhi Biofilm Formation and Dynamics to Understand Antimicrobial Resistance. Life Sci. 2024, 339, 122418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez-Moreno, A.; Gutiérrez-Lomelí, M.; Guerrero-Medina, P.J.; Avila-Novoa, M.G. Biofilm Formation by Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella spp. under Mono- and Dual-Species Conditions and Their Sensitivity to Cetrimonium Bromide, Peracetic Acid and Sodium Hypochlorite. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2018, 49, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yammine, J.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Karam, L.; Ismail, A.; Fadel, A.; Chihib, N.-E. Dynamic Salmonella Enteritidis Biofilms Development under Different Flow Conditions and Their Removal Using Nanoencapsulated Thymol. Biofilm 2022, 4, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Jyung, S.; Kang, D.-H. Comparative Study of Salmonella Typhimurium Biofilms and Their Resistance Depending on Cellulose Secretion and Maturation Temperatures. LWT 2022, 154, 112700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano-Félix, J.A.; Chaidez, C.; Mena, K.D.; Soto-Galindo, M.d.S.; Castro-del Campo, N. Characterization of Biofilm Formation by Salmonella enterica at the Air–Liquid Interface in Aquatic Environments. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Liang, Z.; He, S.; Chin, F.W.L.; Huang, D.; Hong, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, D. Salmonella Dry Surface Biofilm: Morphology, Single-Cell Landscape, and Sanitization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e01623-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Machado, C.; Capita, R.; Riesco-Peláez, F.; Alonso-Calleja, C. Visualization and Quantification of the Cellular and Extracellular Components of Salmonella Agona Biofilms at Different Stages of Development. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, C.; Erdoğan, İ.; Özdemir, K.; Akçelik, N.; Akçelik, M. Comparative Analysis of Biofilm Structures in Salmonella Typhimurium DMC4 Strain and Its dam and seqA Gene Mutants Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) and Raman Spectroscopy Methods. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2025, 56, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counihan, K.L.; Tilman, S.; Uknalis, J.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Niemira, B.A.; Bermudez-Aguirre, D. Attachment and Biofilm Formation of Eight Different Salmonella Serotypes on Three Food-Contact Surfaces at Different Temperatures. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Guragain, M.; Chitlapilly Dass, S.; Palanisamy, V.; Bosilevac, J.M. Impact of Intense Sanitization on Environmental Biofilm Communities and the Survival of Salmonella enterica at a Beef Processing Plant. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1338600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thames, H.T.; Pokhrel, D.; Willis, E.; Rivers, O.; Dinh, T.T.N.; Zhang, L.; Schilling, M.W.; Ramachandran, R.; White, S.; Sukumaran, A.T. Salmonella Biofilm Formation under Fluidic Shear Stress on Different Surface Materials. Foods 2023, 12, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Feng, J.; Ma, L.; de la Fuente Núñez, C.; Gölz, G.; Lu, X. Effects of Meat Juice on Biofilm Formation of Campylobacter and Salmonella. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 253, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, K.; Lin, R.; Xu, X.; Xu, F.; Lin, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Liao, M.; et al. High Levels of Antibiotic Resistance in MDR-Strong Biofilm-Forming Salmonella Typhimurium ST34 in Southern China. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Locke, S.R.; Vinayamohan, P.G.; Diaz-Campos, D.; Habing, G. Biofilm-forming Abilities of Salmonella Serovars Isolated from Clinically Ill Livestock at 48 and 168 h. J. Food Prot. 2025, 88, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, D.K.; Taneja, N.K.; Taneja, P.; Patel, P. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of multi-drug resistant, biofilm forming, human invasive strain of Salmonella Typhimurium SMC25 isolated from poultry meat in India. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 173, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, A.J.; Bijker, E.M. A Guide to Vaccinology: From Basic Principles to New Developments. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.A.G.; Afonina, I.; Kline, K.A. Eradicating Biofilm Infections: An Update on Current and Prospective Approaches. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 63, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micoli, F.; Bagnoli, F.; Rappuoli, R.; Serruto, D. The Role of Vaccines in Combatting Antimicrobial Resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Invasive Disease Collaborators. The global burden of non-typhoidal salmonella invasive disease: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1312–1324.

- Chen, W.H.; Barnes, R.S.; Sikorski, M.J.; Datar, R.; Sukhavasi, R.; Liang, Y.; Rapaka, R.R.; Pasetti, M.F.; Sztein, M.B.; Wahid, R.; et al. A Combination Typhoid and Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Polysaccharide Conjugate Vaccine in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase 1 Trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 4256–4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanumunthadu, B.; Demissie, T.; Greenland, M.; Skidmore, P.; Tanha, K.; Crocker-Buque, T.; Owino, N.; Sciré, A.S.; Crispino, C.; De Simone, D.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella (iNTS)-GMMA vaccine: A first-in-human, randomised, dose escalation trial. eBioMedicine 2025, 119, 105903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loera-Muro, A.; Guerrero-Barrera, A.; Tremblay, D.N.; Hathroubi, S.; Angulo, C. Bacterial biofilm-derived antigens: A new strategy for vaccine development against infectious diseases. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CARB-X. CARB-X Funds Clarametyx Biosciences to Develop Anti-Biofilm Vaccine. 7 January 2025. Available online: https://carb-x.org/carb-x-news/carb-x-funds-clarametyx-biosciences-to-develop-anti-biofilm-vaccine/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Jia, H.J.; Jia, P.P.; Yin, S.; Bu, L.K.; Yang, G.; Pei, D.S. Engineering bacteriophages for enhanced host range and efficacy: Insights from bacteriophage-bacteria interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1172635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mirski, T.; Lidia, M.; Nakonieczna, A.; Gryko, R. Bacteriophages, phage endolysins and antimicrobial peptides—The possibilities for their common use to combat infections and in the design of new drugs. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2019, 26, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.Y.; Nang, S.C.; Chan, H.K.; Li, J. Novel antimicrobial agents for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 187, 114378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, N.N.; Pottker, E.S.; Webber, B.; Borges, K.A.; Duarte, S.C.; Levandowski, R.; Ruschel, L.R.; Rodrigues, L.B. Effect of two lytic bacteriophages against multidrug-resistant and biofilm-forming Salmonella Gallinarum from poultry. Br. Poult. Sci. 2020, 61, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaglan, A.B.; Verma, R.; Vashisth, M.; Virmani, N.; Bera, B.C.; Vaid, R.K.; Anand, T. A novel lytic phage infecting MDR Salmonella enterica and its application as effective food biocontrol. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1387830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Cho, E.; Park, H.; Jeon, B.; Ryu, S. Characterization of the lytic phage MSP1 for the inhibition of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovars Thompson and its biofilm. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 385, 110010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, C.; Wei, B.; Cui, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Xu, Y. Isolation, characterization and comparison of lytic Epseptimavirus phages targeting Salmonella. Food Res. Int. 2021, 147, 110480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, H.J.; Giri, S.S.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, S.B.; Park, S.C. Bacteriophage as an alternative to prevent reptile-associated Salmonella transmission. Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, S.; Ren, H.; Zou, L.; Ma, J.; Liu, W. Characterization of a Salmonella abortus equi phage 4FS1 and its depolymerase. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1496684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Korzeniowski, P.; Śliwka, P.; Kuczkowski, M.; Mišić, D.; Milcarz, A.; Kuźmińska-Bajor, M. Bacteriophage Cocktail Can Effectively Control Salmonella Biofilm in Poultry Housing. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 901770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yüksel, F.N.; Buzrul, S.; Akçelik, M.; Akçelik, N. Inhibition and eradication of Salmonella Typhimurium biofilm using P22 bacteriophage, EDTA and nisin. Biofouling 2018, 34, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taj, M.I.; Guan, P.; Ding, Y.; Zheng, X.; Kong, W.; Wang, X. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of novel phage endolysin lysSEP21 against dual-species biofilm of Salmonella and Escherichia coli and its application in food preservation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 441, 111337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Sun, X.; Lu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ling, X.; Xu, Y.; Liang, R.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; et al. Salmonella Phage vB_SpuM_X5: A Novel Approach to Reducing Salmonella Biofilms with Implications for Food Safety. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugo, M.; Musyoki, A.; Makumi, A. Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages with lytic activity against multidrug-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella from Nairobi City county, Kenya. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jung, L.; Ding, T.; Ahn, J. Evaluation of lytic bacteriophages for control of multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2017, 16, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.M.; Pereira, G.N.; Durli Junior, I.; Teixeira, G.M.; Bertozzi, M.M.; Verri, W.A., Jr.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Nakazato, G. Comparative analysis of effectiveness for phage cocktail development against multiple Salmonella serovars and its biofilm control activity. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gong, C.; Jiang, X. Application of bacteriophages to reduce Salmonella attachment and biofilms on hard surfaces. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 1838–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Var, I.; Al-Matar, M.; Heshmati, B.; Albarri, O. Bacteriophage Cocktail Can Effectively Control Salmonella Biofilm on Gallstone and Tooth Surfaces. Curr. Drug Targets 2023, 24, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouine, N.; El Ghachtouli, N.; El Abed, S.; Ibnsouda Koraichi, S. A Comprehensive Review on Medicinal Plant Extracts as Antibacterial Agents: Factors, Mechanism Insights and Future Prospects. Sci. Afr. 2024, 26, e02395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enioutina, E.Y.; Teng, L.; Fateeva, T.V.; Brown, J.C.S.; Job, K.M.; Bortnikova, V.V.; Krepkova, L.V.; Gubarev, M.I.; Sherwin, C.M.T. Phytotherapy as an Alternative to Conventional Antimicrobials: Combating Microbial Resistance. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 10, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fydrych, D.; Jeziurska, J.; Wełna, J.; Kwiecińska-Piróg, J. Potential Use of Selected Natural Compounds with Anti-Biofilm Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.G.; Lee, J.H.; Gwon, G.; Kim, S.I.; Park, J.G.; Lee, J. Essential Oils and Eugenols Inhibit Biofilm Formation and the Virulence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Demerdash, A.S.; Orady, R.M.; Matter, A.A.; Ebrahem, A.F. An Alternative Approach Using Nano-garlic Emulsion and its Synergy with Antibiotics for Controlling Biofilm-Producing Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella in Chicken. Indian J. Microbiol. 2023, 63, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Narimisa, N.; Khoshbayan, A.; Gharaghani, S.; Razavi, S.; Jazi, F.M. Inhibitory effects of nafcillin and diosmin on biofilm formation by Salmonella Typhimurium. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.G.; Hu, H.X.; Chen, J.Y.; Xue, Y.S.; Kodirkhonov, B.; Han, B.Z. Comparative study on inhibitory effects of ferulic acid and p-coumaric acid on Salmonella Enteritidis biofilm formation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 38, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Wang, Q.; Ren, K.; Xu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Rao, Z.; Zhang, X. A Review of Antimicrobial Peptides: Structure, Mechanism of Action, and Molecular Optimization Strategies. Fermentation 2024, 10, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, B.H.; Gaynord, J.; Rowe, S.M.; Deingruber, T.; Spring, D.R. The Multifaceted Nature of Antimicrobial Peptides: Current Synthetic Chemistry Approaches and Future Directions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 7820–7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.Y.; Khanum, R. Antimicrobial Peptides as Potential Anti-Biofilm Agents against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2017, 50, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande Burgos, M.J.; Lucas López, R.; López Aguayo, M.C.; Pérez Pulido, R.; Gálvez, A. Inhibition of planktonic and sessile Salmonella enterica cells by combinations of enterocin AS-48, polymyxin B and biocides. Food Control 2013, 30, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Zamudio, U.A.; Canizalez-Roman, A.; Flores-Villaseñor, H.; Bolscher, J.G.M.; Nazmi, K.; Leon-Sicairos, C.; Acosta-Smith, E.; Quintero-Martínez, L.E.; León-Sicairos, N. Effect of bovine lactoferrin and lactoferrin-derived peptides on planktonic cells and abiotic surface biofilms of Salmonella enterica. J. Dairy Res. 2025, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, B.K.; Jackman, J.A.; Valle-González, E.R.; Cho, N.-J. Antibacterial Free Fatty Acids and Monoglycerides: Biological Activities, Experimental Testing, and Therapeutic Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.H.; Cámara, M.; He, Y.W. The DSF Family of Quorum Sensing Signals: Diversity, Biosynthesis, and Turnover. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.-S.; Bambace, M.F.; Andersen, E.B.; Meyer, R.L.; Schwab, C. Environmental pH and Compound Structure Affect the Activity of Short-Chain Carboxylic Acids against Planktonic Growth, Biofilm Formation, and Eradication of the Food Pathogen Salmonella enterica. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0165824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, W.; Qin, N.; Ren, X.; Xia, X. Propionate and Butyrate Inhibit Biofilm Formation of Salmonella Typhimurium Grown in Laboratory Media and Food Models. Foods 2022, 11, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, T.; Shah, C.; Zhu, C.; Upadhyaya, I.; Upadhyay, A. Carvacrol and Caprylic Acid Nanoemulsions as Natural Sanitizers for Controlling Salmonella Enteritidis Biofilms on Stainless Steel Surfaces. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojković, D.; Petrović, J.; Carević, T.; Soković, M.; Liaras, K. Synthetic and Semisynthetic Compounds as Antibacterials Targeting Virulence Traits in Resistant Strains: A Narrative Updated Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimann, D.; Kohnhäuser, D.; Kohnhäuser, A.J.; Brönstrup, M. Antibacterials with Novel Chemical Scaffolds in Clinical Development. Drugs 2025, 85, 293–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegelski, L.; Pinkner, J.; Hammer, N.; Cusumano, C.K.; Hung, C.S.; Chorell, E.; Aberg, V.; Walker, J.N.; Seed, P.C.; Almqvist, F.; et al. Small-molecule inhibitors target Escherichia coli amyloid biogenesis and biofilm formation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, E.K.; Bengtsson, C.; Evans, M.L.; Chorell, E.; Sellstedt, M.; Lindgren, A.E.; Hufnagel, D.A.; Bhattacharya, M.; Tessier, P.M.; Wittung-Stafshede, P.; et al. Modulation of Curli Assembly and Pellicle Biofilm Formation by Chemical and Protein Chaperones. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdo, A.; McWhorter, A.; Hasse, D.; Schmitt-John, T.; Richter, K. Efficacy of Plasma-Treated Water against Salmonella Typhimurium: Antibacterial Activity, Inhibition of Invasion, and Biofilm Disruption. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nové, M.; Kincses, A.; Szalontai, B.; Rácz, B.; Blair, J.M.A.; González-Prádena, A.; Benito-Lama, M.; Domínguez-Álvarez, E.; Spengler, G. Biofilm Eradication by Symmetrical Selenoesters for Food-Borne Pathogens. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Gong, Y.; Yuan, B.; Mo, Z.; Tang, H.; Tao, J.; Xu, Z. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of star anise-cinnamon essential oil against multidrug-resistant Salmonella Thompson. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 14, 1463551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, N.-N.; Kim, W.J.; Kang, S.S. Anti-biofilm effect of crude bacteriocin derived from Lactobacillus brevis DF01 on Escherichia coli and Salmonella Typhimurium. Food Control 2019, 98, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.Y.; Kang, S.S. Inhibitory effect of bacteriocin produced by Pediococcus acidilactici on the biofilm formation of Salmonella Typhimurium. Food Control 2020, 117, 107361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.; Price-Whelan, A.; Dietrich, L.E.P. Gradients and Consequences of Heterogeneity in Biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.M.; Flechtner, A.D.; La Perle, K.M.; Gunn, J.S. Visualization of Extracellular Matrix Components within Sectioned Salmonella Biofilms on the Surface of Human Gallstones. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, K.; Nguyen, T.L.; Roberfroid, S.; Schoofs, G.; Verhoeven, T.; De Coster, D.; Vanderleyden, J.; De Keersmaecker, S.C. Gene Expression Analysis of Monospecies Salmonella Typhimurium Biofilms Using Differential Fluorescence Induction. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 84, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vice, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chitlapilly Dass, S.; Wang, R. Microscopic Analysis of Temperature Effects on Surface Colonization and Biofilm Morphology of Salmonella enterica. Foods 2025, 14, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V.C.; Patel, S.K.S.; Lee, J.K. Bacterial Biofilm Inhibitors: An Overview. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 115389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, J.E.; Hahn, M.M.; D’Souza, S.J.; Vasicek, E.M.; Sandala, J.L.; Gunn, J.S.; McLachlan, J.B. Salmonella Biofilm Formation, Chronic Infection, and Immunity Within the Intestine and Hepatobiliary Tract. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 10, 624622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shrestha, N.; Préat, V.; Beloqui, A. An Overview of In Vitro, Ex Vivo and In Vivo Models for Studying the Transport of Drugs across Intestinal Barriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 175, 113795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiardes, S.; Christodoulou, C. Orally Administered Drugs and Their Complicated Relationship with Our Gastrointestinal Tract. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stillhart, C.; Vučićević, K.; Augustijns, P.; Basit, A.W.; Batchelor, H.; Flanagan, T.R.; Gesquiere, I.; Greupink, R.; Keszthelyi, D.; Koskinen, M.; et al. Impact of Gastrointestinal Physiology on Drug Absorption in Special Populations—An UNGAP Review. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 147, 105280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodyra-Stefaniak, K.; Miernikiewicz, P.; Drapała, J.; Drab, M.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Lecion, D.; Kaźmierczak, Z.; Beta, W.; Majewska, J.; Harhala, M.; et al. Mammalian Host-Versus-Phage Immune Response Determines Phage Fate In Vivo. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D. Phage–Host–Immune System Dynamics in Bacteriophage Therapy: Basic Principles and Mathematical Models. Transl. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 31, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kungwani, N.A.; Panda, J.; Mishra, A.K.; Chavda, N.; Shukla, S.; Vikhe, K.; Sharma, G.; Mohanta, Y.K.; Sharifi-Rad, M. Combating Bacterial Biofilms and Related Drug Resistance: Role of Phyto-Derived Adjuvant and Nanomaterials. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 195, 106874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Powers, Z.M.; Kao, C.Y. Defeating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria: Exploring Alternative Therapies for a Post-Antibiotic Era. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyżek, P. Challenges and Limitations of Anti-Quorum Sensing Therapies. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V.C.; Wood, T.K.; Kumar, P. Evolution of Resistance to Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors. Microb. Ecol. 2014, 68, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seukep, A.J.; Nembu, N.E.; Mbuntcha, H.G.; Kuete, V. Bacterial Drug Resistance towards Natural Products. In Advances in Botanical Research; Kuete, V., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; Volume 106, pp. 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oechslin, F. Resistance Development to Bacteriophages Occurring during Bacteriophage Therapy. Viruses 2018, 10, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouvier, F.; Brunel, J.M.; Pagès, J.M.; Vergalli, J. Efflux-Mediated Resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: Recent Advances and Ongoing Challenges to Inhibit Bacterial Efflux Pumps. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, W.; Yang, J.; Gao, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Yuan, X.; Sun, B.; Yang, J.; et al. Mechanisms of Outer Membrane Vesicles in Bacterial Drug Resistance: Insights and Implications. Biochimie 2025, 238, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, X.; Guo, L.; Bao, Z.; Xian, M.; Zhao, G. Efflux Pumps and Porins Enhance Bacterial Tolerance to Phenolic Compounds by Inhibiting Hydroxyl Radical Generation. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bołoz, A.; Lannoy, V.; Olszak, T.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Augustyniak, D. Interplay Between Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles and Phages: Receptors, Mechanisms, and Implications. Viruses 2025, 17, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punchihewage-Don, A.J.; Ranaweera, P.N.; Parveen, S. Defense Mechanisms of Salmonella against Antibiotics: A Review. Front. Antibiot. 2024, 3, 1448796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppi, V.; Scattini, G.; Musa, L.; Stefanetti, V.; Pascucci, L.; Chiaradia, E.; Tognoloni, A.; Giovagnoli, S.; Franciosini, M.P.; Branciari, R.; et al. Evaluation of β-Lactamase Enzyme Activity in Outer Membrane Vesicles (OMVs) Isolated from Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) Salmonella Infantis Strains. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Małaszczuk, M.; Pawlak, A.; Krzyżek, P. Salmonellosis as a One Health–One Biofilm Challenge: Biofilm Formation by Salmonella and Alternative Eradication Strategies in the Post-Antibiotic Era. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010061

Małaszczuk M, Pawlak A, Krzyżek P. Salmonellosis as a One Health–One Biofilm Challenge: Biofilm Formation by Salmonella and Alternative Eradication Strategies in the Post-Antibiotic Era. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleMałaszczuk, Michał, Aleksandra Pawlak, and Paweł Krzyżek. 2026. "Salmonellosis as a One Health–One Biofilm Challenge: Biofilm Formation by Salmonella and Alternative Eradication Strategies in the Post-Antibiotic Era" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010061

APA StyleMałaszczuk, M., Pawlak, A., & Krzyżek, P. (2026). Salmonellosis as a One Health–One Biofilm Challenge: Biofilm Formation by Salmonella and Alternative Eradication Strategies in the Post-Antibiotic Era. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010061