Mapping the Vaginal Metabolic Profile in Dysbiosis, Persistent Human Papillomavirus Infection, and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

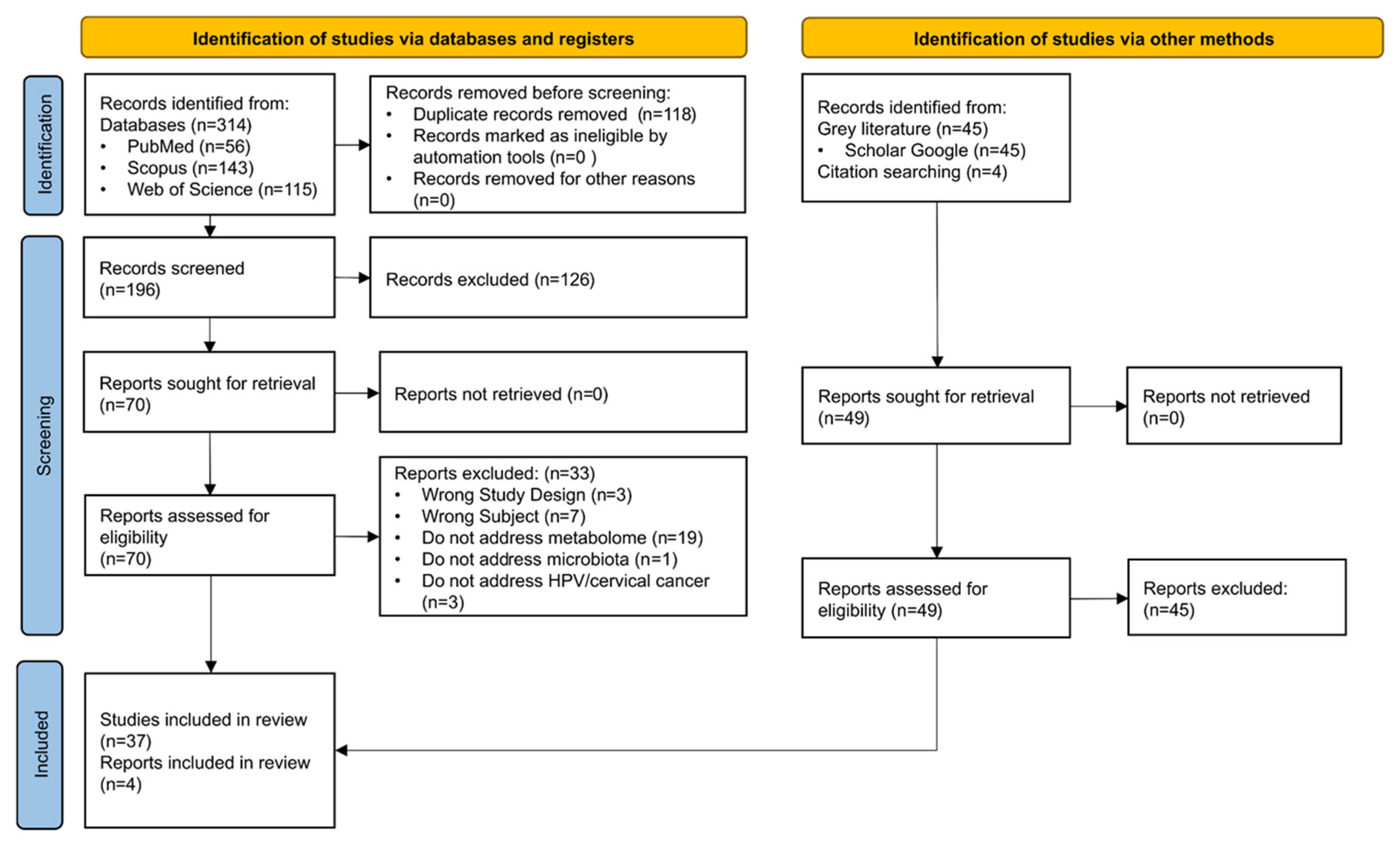

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Microbial Diversity and Composition

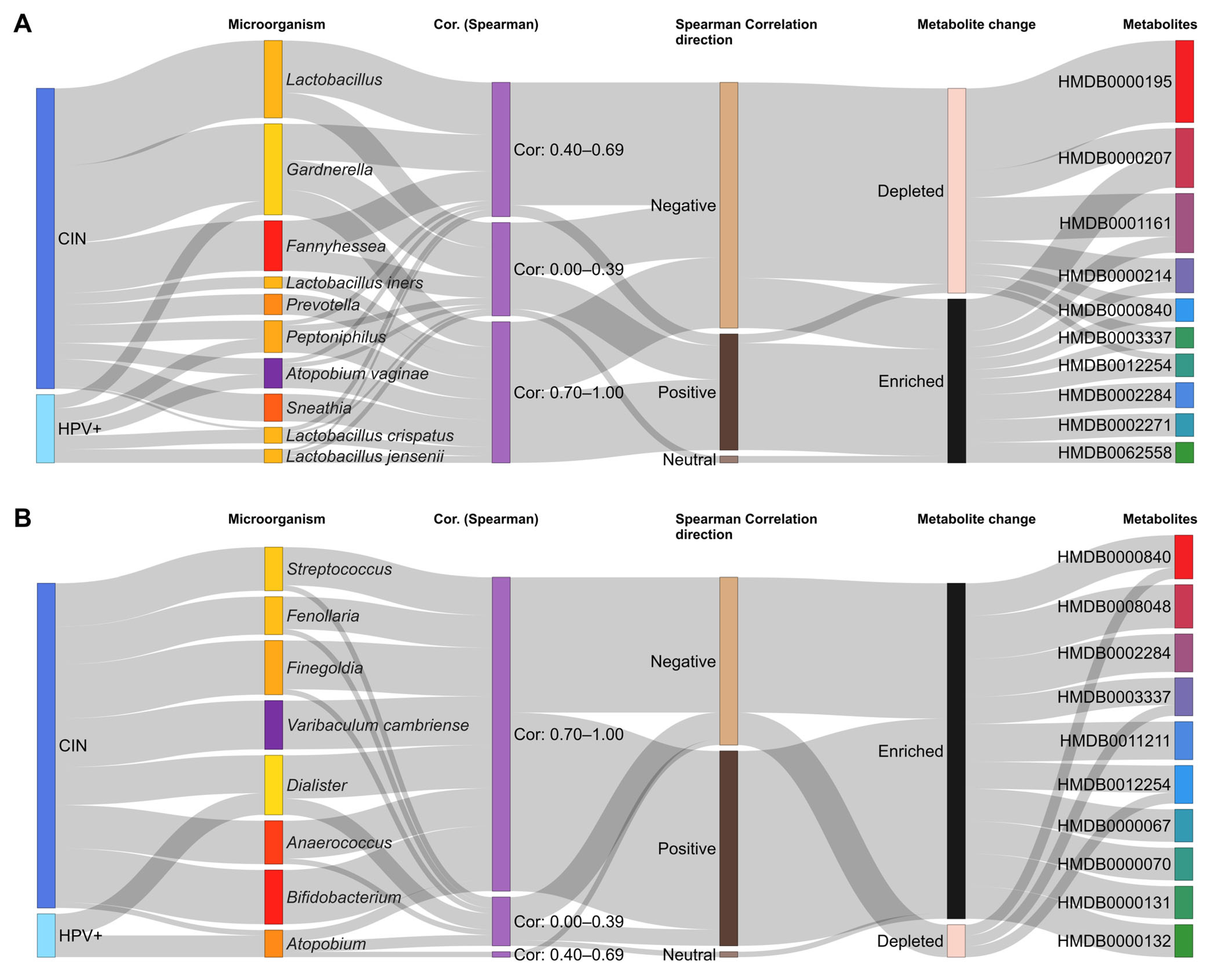

3.3. Metabolomics, Functions, and Correlations with Microorganisms

3.4. In Vitro Studies

3.5. Biomarkers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Query | Search Strategy | Records Identified in Databases | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | #1 | ((Dysbiosis [MH] OR dysbios * [TIAB] OR disbios * [TIAB] OR Dys-symbios * [TIAB] OR “Dys symbiosis” [TIAB] OR Dysbacterios * [TIAB] OR Disbacterios * [TIAB] OR Microbiota [MH] OR microbiota * [TIAB] OR Microbial [TIAB] OR Microbiome * [TIAB] OR Lactobacillus [MH] OR Lactobac * [TIAB]) AND vagin * [TIAB]) OR “Vaginal Diseases” [MH] | 36,041 | 56 |

| #2 | Alphapapillomavirus [MH] OR Alphapapillomavirus * [TIAB] OR HPV [TIAB] OR “Human Papillomavirus *” [TIAB] OR “Papillomavirus E7 Proteins” [MH] | 69,515 | ||

| #3 | “Metabolism” [MH] OR Metabolom * [TIAB] OR Metabolit * [TIAB] OR Metabolic [STIAB] OR “lactic acid” [MH] OR “Hydrogen peroxide” [TIAB] OR “Hydrogen peroxid *” [TIAB] OR metalloprotein * [TIAB] OR sialidase [TIAB] OR “reactive oxygen species” [TIAB] OR “Aromatic amines” OR putrescine [TW] OR cadaverine [TW] OR propionate [TIAB] OR triacylglycerol [TIAB] OR acetoacetate [TIAB] OR Trimethylamine * [TIAB] | 3,796,575 | ||

| SCOPUS | #1 | TITLE-ABS-KEY (((dysbios * OR disbios * OR Dys-symbios * OR “Dys symbiosis” OR Dysbacterios * OR Disbacterios * OR microbiota * OR Microbial OR Microbiome * OR Lactobac *) AND vagin *) OR “Vaginal Diseases”) | 17,035 | 143 |

| #2 | TITLE-ABS-KEY (Alphapapillomavirus * OR HPV OR “Human Papillomavirus *” OR “Papillomavirus E7 Proteins”) | 82,849 | ||

| #3 | TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Metabolism” OR Metabolom * OR Metabolit * OR Metabolic OR “lactic acid” OR “Hydrogen peroxid *” OR metalloprotein * OR sialidase OR “reactive oxygen species” OR “Aromatic amines” OR putrescine OR cadaverine OR propionate OR triacylglycerol OR acetoacetate OR Trimethylamine * OR proteoma OR protein OR enzyme OR bacteriocin) | 6,142,866 | ||

| Web of Science | #1 | (dysbios * OR disbios * OR Dys-symbios * OR “Dys symbiosis” OR Dysbacterios * OR Disbacterios * OR microbiota * OR Microbial OR Microbiome * OR Lactobac *) AND vagin *) OR (“Vaginal Diseases”) | 9546 | 115 |

| #2 | (Alphapapillomavirus * OR HPV OR “Human Papillomavirus*” OR “Papillomavirus E7 Proteins”) | 91,229 | ||

| #3 | (“Metabolism” OR Metabolom * OR Metabolit * OR Metabolic OR “lactic acid” OR “Hydrogen peroxid *” OR metalloprotein * OR sialidase OR “reactive oxygen species” OR “Aromatic amines” OR putrescine OR cadaverine OR propionate OR triacylglycerol OR acetoacetate OR Trimethylamine * OR proteoma OR protein OR enzyme OR bacteriocin) | 3,362,413 |

| Exclusion Criteria | Number of Studies | References |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women | 15 | Borgogna et al., 2020 [42], Li et al., 2024 [59], Liu et al., 2024 [79], Zhang et al., 2024 [61], Li et al., 2024 [63], Lin et al., 2022 [64], Cheng et al., 2024 [62], De Magalhães et al., 2022 [58], Xu et al., 2022 [65], Bokulich et al., 2022 [25], Shi et al., 2024 [75], Feng et al., 2023 [67], Qulu et al., 2023 [83], Dai et al., 2025 [77], Zhao et al., 2025 [68]. |

| Lactating women | 4 | Borgogna et al., 2020 [42], Li et al., 2024 [63], Zhang et al., 2024 [61], Kamble et al., 2022 [56]. |

| Acute or chronic disease | 2 | Borgogna et al., 2020 [42], Qulu et al., 2023 [83]. |

| Antibiotic use in the last 30 days | 16 | Borgogna et al., 2020 [42], Cheng et al., 2024 [38], Li et al., 2024 [59], Liu et al., 2024 [79], Sun et al., 2023 [78], De Magalhães et al., 2022 [58], Choi et al., 2006 [84], Fan et al., 2021 [52], Shi et al., 2024 [75], Feng et al., 2023 [67], Zhaoxi et al., 2021 [81], Kamble et al., 2022 [56], Qulu et al., 2023 [83], Dai et al., 2024 [70], Zhao et al., 2025 [68] |

| Alcohol or drug dependence | 1 | Borgogna et al., 2020 [42] |

| Hormonal therapy | 6 | Cheng et al., 2024 [38], Liu et al., 2024 [79], Fan et al., 2021 [52], Shi et al., 2024 [75], Dai et al., 2025 [77], Zhao et al., 2025 [68] |

| Cervical carcinoma | 5 | Cheng et al., 2024 [62], Li et al., 2024 [59], Li et al., 2024 [63], Choi et al., 2006 [84], Kamble et al., 2022 [56] |

| Vaginal douching within 48 h | 9 | Cheng et al., 2024 [38], Li et al., 2024 [59], Sun et al., 2023 [78], Ou et al., 2024 [57], Li et al., 2020 [80], Choi et al., 2006 [84], Fan et al., 2021 [52], Zhaoxi et al., 2021 [81], Dai et al., 2025 [77] |

| Sexually transmitted infection (STI) | 5 | Cheng et al., 2024 [38], Ou et al., 2024 [57], Lin et al., 2022 [64], Shi et al., 2024 [75], Kamble et al., 2022 [56] |

| Sexual activity in the past 72 h | 10 | Cheng et al., 2024 [38], Li et al., 2024 [59], Ou et al., 2024 [57], Li et al., 2020 [80], Lin et al., 2022 [64], De Magalhães et al., 2022 [58], Shi et al., 2024 [75], Feng et al., 2023 [67], Dai et al., 2025 [77], Zhao et al., 2025 [68] |

| Severe immune disease | 12 | Li et al., 2024 [63], Liu et al., 2024 [79], Li et al., 2024 [59], Sun et al., 2023, Lin et al., 2022 [64], Cheng et al., 2024 [38], Fan et al., 2021 [52], Dai et al., 2024 [70], Feng et al., 2023 [67], Zhaoxi et al., 2021 [81], Qulu et al., 2023 [83], Dai et al., 2025 [77] |

| History of spontaneous abortion | 2 | Liu et al., 2024 [79], Zhang et al., 2024 [61] |

| Menopause | 1 | Liu et al., 2024 [79]. |

| Menstrual period | 3 | Zhang et al., 2024 [61], Ou et al., 2024 [57], Feng et al., 2023 [67]. |

| Hysterectomy | 4 | Zhang et al., 2024 [61], Shi et al., 2024 [75], Feng et al., 2023 [67], Zhao et al., 2025 [68]. |

| Vaccinated against HPV | 3 | Zhang et al., 2024 [61], Li et al., 2024 [63], Feng et al., 2023 [67] |

| Malignant diseases | 2 | Li et al., 2024 [63], Shi et al., 2024 [75] |

| Multiple sexual partners | 1 | Li et al., 2024 [63] |

| HIV infection | 3 | Ou et al., 2024 [57], Dai et al., 2024 [70], Zhao et al., 2025 [68] |

| Vaginal lubricant or cream | 5 | Ou et al., 2024 [57], De Magalhães et al., 2022 [58], Dai et al., 2024 [70], Feng et al., 2023 [67], Zhao et al., 2025 [68] |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 1 | Ou et al., 2024 [57] |

| Endocrine disorders | 1 | Fan et al., 2021 [52] |

| Chemotherapy/ radiotherapy | 2 | Fan et al., 2021 [52], Zhao et al., 2025 [68]. |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.; Gersh, M.; Skovronsky, G.; Moss, C. The Future of Cervical Cancer Screening. Int. J. Womens Health 2024, 16, 1715–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkwabong, E.; Badjan, I.L.B.; Sando, Z. Pap smear accuracy for the diagnosis of cervical precancerous lesions. Trop. Dr. 2019, 49, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Regional Implementation Framework for Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem 2021–2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, B.; Guo, J.; Sheng, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhao, Y. Human Papillomavirus-Negative Cervical Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, e606335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, N. Research progress on human papillomavirus-negative cervical cancer: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e39957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Chung, Y.; Rhee, S.; Kim, T.H. Untold story of human cervical cancers: HPV-negative cervical cancer. BMB Rep. 2022, 55, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimple, S.; Mishra, G. Cancer cervix: Epidemiology and disease burden. Cytojournal 2022, 19, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Rowley, J.; Alemany, L.; Arbyn, M.; Giuliano, A.R.; Markowitz, L.E.; Broutet, N.; Taylor, M. Global and regional estimates of genital human papillomavirus prevalence among men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, 1345–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynor, D.; Martin, C.M.; White, C.; Reynolds, S.; D’Arcy, T.; O’Leary, J.J.; Lyng, F.M. Raman Spectroscopy of Liquid-Based Cervical Smear Samples as a Triage to Stratify Women Who Are HPV-Positive on Screening. Cancers 2021, 13, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, L.L.; Richtmann, R. HPV vaccination programs in LMIC: Is it time to optimize schedules and recommendations? J. Pediatr. 2023, 99, S57–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liang, H.; Yan, Y.; Bian, R.; Huang, W.; Zhang, X.; Nie, J. Distribution of HPV types among women with HPV-related diseases and exploration of lineages and variants of HPV 52 and 58 among HPV-infected patients in China: A systematic literature review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, e2343192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudula, A.; Rouzi, N.; Xu, L.; Yang, Y.; Hasimu, A. Tissue-based metabolomics reveals potential biomarkers for cervical carcinoma and HPV infection. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 2020, 20, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faktor, J.; Henek, T.; Hernychova, L.; Singh, A.; Vojtesek, B.; Polom, J.; Bhatia, R.; Polom, K.; Cuschieri, K.; Cruickshank, M.; et al. Metaproteomic analysis from cervical biopsies and cytologies identifies protein-aceous biomarkers representing both human and microbial species. Talanta 2024, 278, e126460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platz-Christensen, J.J.; Sundstrom, E.; Larsson, P.G. Bacterial vaginosis and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1994, 73, 586–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maarsingh, J.D.; Łaniewski, P.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. Immunometabolic and potential tumor-promoting changes in 3D cervical cell models infected with bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, e725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, M.; Qin, L.; Wan, B.; Wang, H. A meta-analysis of the relationship between vaginal microecology, human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2019, 14, e2019. [Google Scholar]

- Muzny, C.A.; Cerca, N.; Elnaggar, J.H.; Taylor, C.M.; Sobel, J.D.; Van Der Pol, B. State of the Art for Diagnosis of Bacterial Vaginosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e0083722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usyk, M.; Zolnik, C.P.; Castle, P.E.; Porras, C.; Herrero, R.; Gradissimo, A.; Gonzalez, P.; Safaeian, M.; Schiffman, M.; Burk, R.D.; et al. Cervicovaginal microbiome and natural history of HPV in a longitudinal study. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Song, Y.-M.; Lee, K.; Han, M.J.; Sung, J.; Ko, G. Association of the Vaginal Microbiota with Human Papillomavirus Infection in a Korean Twin Cohort. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Qi, X. Vaginal microecology and its role in human papillomavirus infection and human papillomavirus associated cervical lesions. APMIS 2023, 132, 928–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frąszczak, K.; Barczyński, B.; Kondracka, A. Does Lactobacillus Exert a Protective Effect on the Development of Cervical and Endometrial Cancer in Women? Cancers 2022, 14, 4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audirac-Chalifour, A.; Torres-Poveda, K.; Bahena-Román, M.; Téllez-Sosa, J.; Martínez-Barnetche, J.; Cortina-Ceballos, B.; López-Estrada, G.; Delgado-Romero, K.; I Burguete-García, A.; Cantú, D.; et al. Cervical Microbiome and Cytokine Profile at Various Stages of Cervical Cancer: A Pilot Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-J.; Song, J.-H.; Yu, C.-X.; Wang, F.; Wang, P.-C.; Meng, J.-W. Difference in vaginal microecology, local immunity and HPV infection among childbearing-age women with different degrees of cervical lesions in Inner Mongolia. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Łaniewski, P.; Adamov, A.; Chase, D.M.; Caporaso, J.G.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. Multi-omics data integration reveals metabolome as the top predictor of the cervicovaginal microenvironment. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1009876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; MacIntyre, D.A.; Ntritsos, G.; Smith, A.; Tsilidis, K.K.; Marchesi, J.R.; Bennett, P.R.; Moscicki, A.-B.; Kyrgiou, M. The vaginal microbiota associates with the regression of untreated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 lesions. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.A.; Yang, E.J.; Kim, N.R.; Hong, S.R.; Lee, J.-H.; Hwang, C.-S.; Shim, S.-H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, T.J. Changes of vaginal microbiota during cervical carcinogenesis in women with human papillomavirus infection. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Li, Q.; Wan, Z.; OuYang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Exploring the Association Between Cervical Microbiota and HR-HPV Infection Based on 16S rRNA Gene and Metagenomic Sequencing. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 922554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, G. Lactobacilli-mediated control of vaginal cancer through specific reactive oxygen species interaction. Med. Hypotheses 2001, 57, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borella, F.; Carosso, A.R.; Cosma, S.; Preti, M.; Collemi, G.; Cassoni, P.; Bertero, L.; Benedetto, C. Gut Microbiota and Gynecological Cancers: A Summary of Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Future Directions. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 987–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanheira, C.P.; Sallas, M.L.; Nunes, R.A.L.; Lorenzi, N.P.C.; Termini, L. Microbiome and Cervical Cancer. Pathobiology 2020, 88, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Du, H.; Li, S.; Wu, R. Cervicovaginal Microbiome Factors in Clearance of Human Papillomavirus Infection. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 722639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, Z.E.; Łaniewski, P.; Thomas, N.; Roe, D.J.; Chase, D.M.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. Deciphering the complex interplay between microbiota, HPV, inflammation and cancer through cervicovaginal metabolic profiling. EBioMedicine 2019, 44, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Creek, D.J. Discovery and Validation of Clinical Biomarkers of Cancer: A Review Combining Metabolomics and Proteomics. Proteomics 2018, 19, e1700448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wu, Y.; Quan, L.; Yang, W.; Lang, J.; Tian, G.; Meng, B. Research of cervical microbiota alterations with human papillomavirus infection status and women age in Sanmenxia area of China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1004664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorna, N.; Romaguera, J.; Godoy-Vitorino, F. Cervicovaginal Microbiome and Urine Metabolome Paired Analysis Reveals Niche Partitioning of the Microbiota in Patients with Human Papilloma Virus Infections. Metabolites 2020, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zou, K.; Zou, L. Research progress of metabolomics in cervical cancer. Eur. J. Med Res. 2023, 28, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Luo, H.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Su, J. Correlation between Indicators of Vaginal Microbiota and Human Papillomavirus Infection: A Retrospective Study. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 51, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, N.; Zheng, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Song, L.; Lyu, Y.; et al. Vaginal micro-environment disorder promotes malignant prognosis of low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A prospective community cohort study in Shanxi Province, China. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 2738–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Yang, W.; Yan, R.; Chi, J.; Xia, Q.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, P. Co-evolution of vaginal microbiome and cervical cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Xie, X.; Lu, W. The Alterations of Vaginal Microbiome in HPV16 Infection as Identified by Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgogna, J.; Shardell, M.D.; Santori, E.; Nelson, T.; Rath, J.; Glover, E.; Ravel, J.; Gravitt, P.; Yeoman, C.; Brotman, R. The vaginal metabolome and microbiota of cervical HPV-positive and HPV-negative women: A cross-sectional analysis. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 127, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yu, H.; Gao, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Ma, X.; Dong, M.; Li, B.; Bai, J.; et al. Leveraging 16S rRNA data to uncover vaginal microbial signatures in women with cervical cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1024723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: North Adelaide, Australia, 2024; Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355862497/10.+Scoping+reviews (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, T.; Rasband, W. ImageJ User Guide. USA: National Institutes of Health 2011. Available online: https://imagej.net/ij/docs/guide/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawar, K.; Aranha, C. Lactobacilli metabolites restore E-cadherin and suppress MMP9 in cervical cancer cells. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 3, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Q.; Wu, Y.; Li, M.; An, F.; Yao, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Yuan, J.; Jiang, K.; Li, W.; et al. Lactobacillus spp. create a protective micro-ecological environment through regulating the core fucosylation of vaginal epithelial cells against cervical cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motevaseli, E.; Shirzad, M.; Akrami, S.M.; Mousavi, A.-S.; Mirsalehian, A.; Modarressi, M.H. Normal and tumour cervical cells respond differently to vaginal lactobacilli, independent of pH and lactate. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013, 62, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, S.; Tanturli, M.; Mattiuz, G.; Antonelli, A.; Baccani, I.; Bonaiuto, C.; Baldi, S.; Nannini, G.; Menicatti, M.; Bartolucci, G.; et al. Vaginal Lactobacilli and Vaginal Dysbiosis-Associated Bacteria Differently Affect Cervical Epithelial and Immune Homeostasis and Anti-Viral Defenses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.-D.; Xu, D.-J.; Wang, B.-Y.; Yan, D.-H.; Lv, Z.; Su, J.-R. Inhibitory Effect of Vaginal Lactobacillus Supernatants on Cervical Cancer Cells. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2017, 10, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, A.; Naik, S.; Talathi, M.; Jadhav, D.; Pingale, S.; Kaul-Ghanekar, R. Cervicovaginal microbiota isolated from healthy women exhibit probiotic properties and antimicrobial activity against pathogens isolated from cervical cancer patients. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Kang, Y.; Medlegeh; Fu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W. An analysis of the vaginal microbiota and cervicovaginal metabolomics in cervical lesions and cervical carcinoma. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Magalhães, C.C.B.; Linhares, I.M.; Masullo, L.F.; Eleutério, R.M.N.; Witkin, S.S.; Eleutério, J. Comparative measurement of D- and L-lactic acid isomers in vaginal secretions: Association with high-grade cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 305, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Wang, C.B.; Meng, J.B.; Wang, H.B.; Jin, H.B. Investigation of the relationship between the changes in vaginal microecological enzymes and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Medicine 2024, 103, e37068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Shui, Y.; Qian, Y. A Crosstalk Analysis of high-risk human papillomavirus, microbiota and vaginal metabolome in cervicovaginal microenvironment. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 194, 106826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, D.; Huang, R.; Deng, X.; Li, M.; Du, F.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. HPV-associated cervicovaginal microbiome and host metabolome characteristics. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Yan, C.; Yang, Y.; Hong, F.; Du, J. Exploring the Clinical Signatures of Cervical Dysplasia Patients and Their Association With Vaginal Microbiota. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jin, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, H.; Gong, S.; Jiang, L. Reconnoitering correlation between human papillomavirus infection-induced vaginal microecological abnormality and squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) progression. BMC Women’s Health 2024, 24, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Dong, B.; Xue, H.; Lei, H.; Lu, Y.; Wei, X.; Sun, P. Changes of the vaginal microbiota in HPV infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A cross-sectional analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, L.; Xu, F.; Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, D.; Chen, Y.; et al. Microbiome-metabolome analysis reveals cervical lesion alterations. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2022, 54, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhao, S.; Shan, J.; Ren, Q. Metabolomic and microbiota profiles in cervicovaginal lavage fluid of women with high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Hou, Y.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.-Y.; Li, P.-P.; Guo, Y.; An, R.-F. Correlation analysis of vaginal microecology and different types of human papillomavirus infection: A study conducted at a hospital in northwest China. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1138507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, H.; Lv, A.; Zhang, S.; Hui, Y.; Qi, W.; Zhao, H.; Miao, M.; Wang, Y.; Yin, Y.; et al. Vaginal Microbiome and Metabolome Profiles Among HPV Positive and HPV Negative Women Based on Stratification of Vaginitis. J. Med. Virol. 2025, 97, e70385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, N.R.; Mancilla, V.; Łaniewski, P.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. Immunometabolic Contributions of Atopobiaceae Family Members in Human Papillomavirus Infection, Cervical Dysplasia, and Cancer. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 232, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Du, H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Hou, J.; Guo, C.; Yang, Q.; Li, C.; Xie, S.; et al. Metabolic profiles outperform the microbiota in assessing the response of vaginal microenvironments to the changed state of HPV infection. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-J.; Miao, J.-R.; Wu, Q.; Yu, C.-X.; Mu, L.; Song, J.-H. Correlation between HPV-negative cervical lesions and cervical microenvironment. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 59, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.C.; Song, J.H. The correlation between vaginal microecological changes and HPV outcome in patients with cervical lesions in the Inner Mongolia area of China. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 10, 5711–5720. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, S.; Ji, A.; Zhang, C.; Shi, S. Correlation between Vaginal Microecological Status and Prognosis of CIN Patients with High-Risk HPV Infection. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 3620232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Zeng, D.; Chen, W.; Li, F.; Zhong, H.; Fu, J.; Liu, H.; Ying, T.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; et al. Focused ultrasound: A novel therapy for improving vaginal microecology in patients with high-risk HPV infection. Int. J. Hyperth. 2023, 40, 2211276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Dong, X.Y.; Yimingjiang, M.W.L.D.; Ma, W.M.; Ma, Z.P.; Pang, X.L.; Zhang, W. The association between human papillomavirus infection, vaginal microecology, and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women from Xinjiang, China. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2024, 50, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Rajendra, W.; Valluru, L. Evaluation of Microbial Enzymes in Normal and Abnormal Cervicovaginal Fluids of Cervical Dysplasia: A Case Control Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 716346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xu, R.; Guo, C.; Hou, J.; Wu, D.; Li, C.; Du, H.; Wu, R. The inferred modulation of correlated vaginal microbiota and metabolome by cervical differentially expressed genes across distinct CIN grades. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Sun, L.; Li, L.; Xu, W. The Immunomodulation Role of Vaginal Microenvironment On Human Papillomavirus Infection. Galen Med J. 2023, 12, e2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-M.; Zhang, F.; Cai, H.-Y.; Lv, Y.-M.; Pi, M.-Y. Cross-Sectional Study on the Correlation Between Vaginal Microecology and High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infection: Establishment of a Clinical Prediction Model. Int. J. Women’s Health 2024, 16, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ding, L.; Gao, T.; Lyu, Y.; Wang, M.; Song, L.; Li, X.; Gao, W.; Han, Y.; Jia, H.; et al. Association between Vaginal Micro-environment Disorder and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia in a Community Based Population in China. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Sun, B.; Zhang, D. Human papillomavirus genotyping and vaginal microbial metabolites in 276 patients with atypical cervical squamous cells and the clinical effect of nano-silver after loop electrosurgical excision procedure. Mater. Express 2021, 11, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venancio, P.A.; Consolaro, M.E.L.; Derchain, S.F.; Boccardo, E.; Villa, L.L.; Maria-Engler, S.S.; Campa, A.; Discacciati, M.G. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase expression in HPV infection, SILs, and cervical cancer. Cancer Cytopathol. 2019, 127, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qulu, W.; Mtshali, A.; Osman, F.; Ndlela, N.; Ntuli, L.; Mzobe, G.; Naicker, N.; Garrett, N.; Rompalo, A.; Mindel, A.; et al. High-risk human papillomavirus prevalence among South African women diagnosed with other STIs and BV. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, S.M.; Oh, J.S. Hydrogen Peroxide Producing Lactobacilli in Women with Cervical Neoplasia. Cancer Res. Treat. 2006, 38, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, N.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Han, L. Vaginal colonization of Lactobacilli: Mechanism and function. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 198, 107141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.P.; Reddi, V. Significance of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2023, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ma, Y.; Li, R.; Chen, X.; Wan, L.; Zhao, W. Associations of Cervicovaginal Lactobacilli With High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infection, Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizhan, D.; Ukybassova, T.; Bapayeva, G.; Aimagambetova, G.; Kongrtay, K.; Kamzayeva, N.; Terzic, M. Cervicovaginal Microbiome: Physiology, Age-Related Changes, and Protective Role Against Human Papillomavirus Infection. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimena, S.; Davis, J.; Fichorova, R.N.; Feldman, S. The vaginal microbiome: A complex milieu affecting risk of human papillomavirus persistence and cervical cancer. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2022, 46, 100877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudela, E.; Liskova, A.; Samec, M.; Koklesova, L.; Holubekova, V.; Rokos, T.; Kozubik, E.; Pribulova, T.; Zhai, K.; Busselberg, D.; et al. The interplay between the vaginal microbiome and innate immunity in the focus of predictive, preventive, and personalized medical approach to combat HPV-induced cervical cancer. EPMA J. 2021, 12, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; MacIntyre, D.A.; Marchesi, J.R.; Lee, Y.S.; Bennett, P.R.; Kyrgiou, M. The vaginal microbiota, human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: What do we know and where are we going next? Microbiome 2016, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paola, M.; Sani, C.; Clemente, A.M.; Iossa, A.; Perissi, E.; Castronovo, G.; Tanturli, M.; Rivero, D.; Cozzolino, F.; Cavalieri, D.; et al. Characterization of cervico-vaginal microbiota in women developing persistent high-risk Human Papillomavirus infection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Vodstrcil, L.; Hocking, J.S.; Law, M.; Walker, S.; Tabrizi, S.N.; Fairley, C.K.; Bradshaw, C.S. Hormonal Contraception Is Associated with a Reduced Risk of Bacterial Vaginosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, F.; Birse, K.; Hasselrot, K.; Noël-Romas, L.; Introini, A.; Wefer, H.; Seifert, M.; Engstrand, L.; Tjernlund, A.; Broliden, K.; et al. The vaginal microbiome amplifies sex hormone-associated cyclic changes in cervicovaginal inflammation and epithelial barrier disruption. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2018, 80, e12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendharkar, S.; Skafte-Holm, A.; Simsek, G.; Haahr, T. Lactobacilli and Their Probiotic Effects in the Vagina of Reproductive Age Women. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- France, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Brown, S.; Ma, B.; Ravel, J. Towards a deeper understanding of the vaginal microbiota. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraf, V.S.; Sheikh, S.A.; Ahmad, A.; Gillevet, P.M.; Bokhari, H.; Javed, S. Vaginal microbiome: Normalcy vs. dysbiosis. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 3793–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, H.; Bauer, G. Lactobacilli enhance reactive oxygen species-dependent apoptosis-inducing signaling. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaneechoutte, M. The human vaginal microbial community. Res. Microbiol. 2017, 168, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S.; Soltani, A.; Hashemy, S.I. Oxidative stress in cervical cancer pathogenesis and resistance to therapy. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 120, 6868–6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despot, A.; Fureš, R.; Despot, A.-M.; Mikuš, M.; Zlopaša, G.; D’aMato, A.; Chiantera, V.; Serra, P.; Etrusco, A.; Laganà, A.S. Reactive oxygen species within the vaginal space: An additional promoter of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and uterine cervical cancer development? Open Med. 2023, 18, 20230826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachedjian, G.; O’hAnlon, D.E.; Ravel, J. The implausible “in vivo” role of hydrogen peroxide as an antimicrobial factor produced by vaginal microbiota. Microbiome 2018, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Dong, Y.; Bai, J.; Li, H.; Ma, X.; Li, B.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Qi, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. Interactions between microbiota and cervical epithelial, immune, and mucus barrier. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1124591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Qian, Q. Lactic Acid: No Longer an Inert and End-Product of Glycolysis. Physiology 2017, 32, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Da, M.; Zhang, W.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, C.; Han, S. Role of Lactobacillus in cervical cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearps, A.; Tyssen, D.; Srbinovski, D.; Bayigga, L.; Diaz, D.J.D.; Aldunate, M.; Cone, R.; Gugasyan, R.; Anderson, D.; Tachedjian, G. Vaginal lactic acid elicits an anti-inflammatory response from human cervicovaginal epithelial cells and inhibits production of pro-inflammatory mediators associated with HIV acquisition. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 1480–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torcia, M.G. Interplay among Vaginal Microbiome, Immune Response and Sexually Transmitted Viral Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Läsche, M.; Urban, H.; Gallwas, J.; Gründker, C. HPV and Other Microbiota; Who’s Good and Who’s Bad: Effects of the Microbial Environment on the Development of Cervical Cancer—A Non-Systematic Review. Cells 2021, 10, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, B.; Cruciani, F.; Picone, G.; Parolin, C.; Donders, G.; Laghi, L. Vaginal microbiome and metabolome highlight specific signatures of bacterial vaginosis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challa, A.; Maras, J.S.; Nagpal, S.; Tripathi, G.; Taneja, B.; Kachhawa, G.; Sood, S.; Dhawan, B.; Acharya, P.; Upadhyay, A.D.; et al. Multi-omics analysis identifies potential microbial and metabolite diagnostic biomarkers of bacterial vaginosis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 1152–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Xia, B.; Wang, W.; Cheng, J.; Yin, M.; Xie, H.; Li, J.; Ma, L.; Yang, C.; Li, A.; et al. A Comprehensive Analysis of Metabolomics and Transcriptomics in Cervical Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.; Nam, A.; Settle, C.; Overton, M.; Giddens, M.; Richardson, K.P.; Piver, R.; Mysona, D.P.; Rungruang, B.; Ghamande, S.; et al. Serum Proteomic Signatures in Cervical Cancer: Current Status and Future Directions. Cancers 2024, 16, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Wu, J.; Duan, Z.; Luo, M.; Jia, Y. Vaginal metabolic profiling reveals biomarkers characteristics of high-risk HPV infection and cervical lesions. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2025, 51, e70035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Yun, K.; Mun, S.; Chung, W.-H.; Choi, S.-Y.; Nam, Y.-D.; Lim, M.Y.; Hong, C.P.; Park, C.; Ahn, Y.J.; et al. The effect of taxonomic classification by full-length 16S rRNA sequencing with a synthetic long-read technology. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morsli, M.; Gimenez, E.; Magnan, C.; Salipante, F.; Huberlant, S.; Letouzey, V.; Lavigne, J.-P. The association between lifestyle factors and the composition of the vaginal microbiota: A review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 43, 1869–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amabebe, E.; Tatiparthy, M.; Kammala, A.K.; Richardson, L.S.; Taylor, B.D.; Sharma, S.; Menon, R. Vaginal pharmacomicrobiomics modulates risk of persistent and recurrent bacterial vaginosis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, H.; Merchant, M.; Haque, M.M.; Mande, S.S. Crosstalk Between Female Gonadal Hormones and Vaginal Microbiota Across Various Phases of Women’s Gynecological Lifecycle. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeer, S.; Ahannach, S.; Gehrmann, T.; Wittouck, S.; Eilers, T.; Oerlemans, E.; Condori, S.; Dillen, J.; Spacova, I.; Donck, L.V.; et al. A citizen-science-enabled catalogue of the vaginal microbiome and associated factors. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 2183–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.D.; Acharya, K.D.; Zhu, J.E.; Deveney, C.M.; Walther-Antonio, M.R.S.; Tetel, M.J.; Chia, N. Daily Vaginal Microbiota Fluctuations Associated with Natural Hormonal Cycle, Contraceptives, Diet, and Exercise. mSphere 2020, 5, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Omics Approach | Sample Size | HPV (−), (n) | HPV (+), (n) | Cytology/ Histology Performed | Bacterial Taxa or Strains Associated with HPV-Positive Contexts | Significant Metabolites (HPV/Lesions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faktor et al., 2024 [14] | Scotland, Poland and Czech Republic | Cross sectional | Omics | 6 | 0 | 1 | YES | ↑ Lactobacillus iners, L. crispatus, Prevotella, Gardnerella, Sneathia, Fusobacterium, Helicobacter | ↓ Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, ↓ Pyruvate kinase (HPV+) |

| Zheng et al., 2019 [24] | China | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 532 | 154 | 378 | YES | ↑ BV, Trichomonas vaginalis, Chlamydia spp. ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↓ H2O2, ↑ Sialidase, ↑ GUS, ↑ GADP (HPV+/Lesions) |

| Bokulich et al., 2022 [25] | USA | Cross sectional | Multi- omics | 72 | 18 | 54 | YES | ↑ Prevotella bivia, Peptoniphilus, Streptococcus anginosus, Atopobium vaginae, Sneathia sanguinegens, Veillonellales, Finegoldia, Mobiluncus ↓ Lactobacillus crispatus, L. iners | ↑ 3-Hydroxybutyrate, ↑ Deoxycarnitine, ↑ Pipecolate (HPV+/ICC); ↓ Maltopentaose |

| Chorna et al., 2020 [36] | Puerto Rico | Cross sectional | Multi- omics | 19 | 8 | 11 | NR | ↑ Lactobacillus sp., Atopobium vaginae, Gardnerella, Shuttleworthia ↓ Lactobacillus iners, Megasphaera | ↑ Acetate, ↑ Proline, ↑ Threonine (HPV+); ↑ Succinate (HPV−) |

| Cheng et al., 2024 [38] | CSO b | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 5.099 | 4.463 | 636 | NR | ↑ BV, clue cells↓ Lactobacillus (in the normal microbiota) | ↑ Sialidase (HPV+) |

| Liu et al., 2024 [39] | China | Prospective study | Non- omics | 466 | 326 | 140 | YES | ↑ BV-associated profile, ↓ Lactobacillus spp. (inferred) | ↑ GUS, ↑ LE, ↑ SNA (significant only in HR-HPV+ women with CIN1) |

| Borgogna et al., 2020 [42] | USA | Cross sectional | Multi- omics | 39 | 13 | 26 | NR | ↑ Gardnerella vaginalis, Eggerthella, Atopobium (≠A. vaginae), Dialister spp., Gemella ↓ Bifidobacteriaceae, Atopobium vaginae | ↑ Putrescine, ↑ Ethanolamine, ↓ GSH, ↓ Choline phosphate, ↑ N-acetyl-cadaverine (HPV+) |

| Pawar et al., 2022 [51] | India | Experimental in vitro | Non- omics | NA | NA | NA | NA | Lactobacillus vaginalis and L. salivarius—lowest IC50 **** on HPV16+ (SiHa) and HPV18+ (HeLa) cell lines | ↑ L-lactic acid, ↑ H2O2, ↑ E-cadherin, ↓ MMP9 (HPV+ CC) |

| Fan et al., 2021 [52] | China | Experimental in vitro/in vivo | Multi- omics | 119 | 9 | 110 | YES | Protective: Lactobacillus iners—↓ proliferation and migration of cervical cancer cells | ↓ Lactate (in vivo); ↑ Core fucosylation (Lactate-induced in vitro, HPV+, cervical cancer) |

| Motevaseli et al., 2013 [53] | Iran | Experimental in vitro | Non- omics | NA | NA | NA | NA | Protective: Lactobacillus crispatus, L. gasseri—↓ proliferation of cervical cancer cells, ↓ apoptosis | ↓ Caspase-3 activity (in HeLa, HPV18+) |

| Nicolò et al., 2021 [54] | Italy | Experimental in vitro | Non- omics | NA | NA | NA | NA | Protective: L. gasseri, L. jensenii, L. crispatus Detrimental: G. vaginalis, A. vaginae, P. bivia, M. micronuciformis | ↑ Butyrate e valerate, ↓ Acetate |

| Wang et al., 2018 [55] | China | Experimental in vitro | Non-omics | NA | NA | NA | NA | Protective: L. crispatus, L. jensenii, L. gasseri—↓ proliferation of cervical cancer cells, | ↓ HPV16 E6/E7, ↓ CDK2, ↓ Cyclin A, ↑ p21, ↓ cell viability (HPV16+) |

| Kamble et al., 2022 [56] | India | Experimental in vitro | Omics | 53 | NR | NR | YES | Protective: Lactobacillus gasseri, L. fermentum, L. delbrueckii, Enterococcus faecium—antimicrobial activity against pathogens isolated from LSIL, HSIL, and ICC patients | None (no significant association with HPV or lesions) |

| Ou et al., 2024 [57] | China | Cross sectional | Multi- omics | 100 | NR | NR | YES | ↑ Gardnerella, Prevotella, Streptococcus, Atopobium ↓ Lactobacillus crispatus | ↑ N,N′-Diacetylbenzidine, ↑ Oxidized glutathione (CC); ↑ Valyl-glutamate (CC); ↑ 4-Hydroxydebrisoquine (lCIN3) |

| de Magalhães et al., 2021 [58] | Brazil | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 78 | 78 | NR | YES | ↑ Lactobacillus iners | ↑ L-lactic acid (HSIL) |

| Li et al., 2024 [59] | China | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 1.281 | 772 | 509 | NR | ↑ BV ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↑ Prolyl aminopeptidase (HPV+) ↑ Acetylglucosaminidase (HPV+) |

| Yang et al., 2024 [60] | China | Cross sectional | Multi- omics | 26 | 9 | 17 | NR | ↑ Prevotella, Sneathia, Atopobium, Bifidobacteriaceae ↓ Lactobacillus | ↑ 5′-O-Methylmelledonal, ↑ DG(9D3/11M3/0:0), ↑ Glutaminylglutamine, ↑ 2,4-Diisopropyl-3-methylphenol (HPV16+); ↑ Calonectrin, ↑ Longifolonine, ↑ N-Benzylphthalimide (HPV18+) |

| Zhang et al., 2024 [61] | China | Cross sectional | Multi- omics | 42 | 17 | 25 | NR | ↑ Sneathia amnii, Gardnerella, Atopobium, Mycoplasma, Ureaplasma parvum, Veillonella montpellierensis, Aerococcus christensenii ↓ Lactobacillus, Lactobacillus iners | ↑ 9,10-DiHOME, ↑ α-linolenic acid, ↑ ethylparaben, ↑ glycocholic acid, ↑ prostaglandin F3α, ↑ pipecolic acid, ↓ S-lactoylglutathione, ↓ 3-methylcrotonylglycine (HPV+) |

| Cheng et al., 2024 [62] | China | Cross sectional | Omics | 254 | 58 | 196 | YES | ↑ Burkholderiaceae, Acinetobacter, Streptococcus, Dialister, Anaerococcus ↓ Lactobacillus crispatus, Pelomonas, Ochrobactrum | ↓ H2O2 (HPV+, CIN, CC) |

| Li et al. 2024 [63] | China | Longitudinal Prospective | Non- omics | 1.281 | 898 | 383 | NR | ↑ G. vaginalis, yeasts (Candida spp.); ↓ L. acidophilus | ↑ GUS; ↑ SNA, ↑ LE (HPV+) |

| Lin et al., 2022 [64] | China | Cross sectional | Omics | 448 | 310 | 138 | YES | ↑ Gardnerella, Prevotella ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↑ Sialidase (HPV+, CIN+) |

| Xu et al., 2022 [65] | China | Cross sectional | Omics | 40 | 10 | 30 | YES | ↑ Prevotella, Gardnerella, Aquabacterium ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↑ Lipids (CC); ↓ Lipids (LSIL, HSIL) |

| Shen et al., 2025 [66] | China | Cross sectional | Multi- omics | 156 | 0 | 156 | YES | ↑ Atopobium, Sneathia, Pseudomonas ↓ Streptococcus | ↑ N-methylalanine, ↑ phenylacetaldehyde, ↑ glucose-6-phosphate, ↓ Sucrose, ↑ DL-p-hydroxylphenyllactic acid, ↑ guanine (HSIL/HPV+) |

| Feng et al., 2023 [67] | China | Cross sectional | Non-omics | 2.358 | 1.880 | 478 | NR | ↑ BV, Trichomonas vaginalis ↓ Candida spp. (VVC) | ↑ SNA (HPV other subtypes) |

| Zhao et al., 2025 [68] | China | Case–control | Multi-omics | 164 | 123 | 41 | NR | ↑ Lactobacillus iners, Mycoplasma (HPV+ with vaginitis) ↑ Gardnerella, Mycoplasma, Ureaplasma (HPV+ without vaginitis) | ↑ methionyl-alanine, ↓ lipids (HPV+) |

| Jimenez et al., 2024 [69] | USA | Cross sectional | Multi- omics | 99 | 20 | 31 | YES | Protective: Lactobacillus gasseri, L. jensenii—↓ migration and proliferation, ↑ apoptosis | ↑ 2-HG, ↑ 4-hidroxibutirato, ↓ Isobutyrilcarnitine, ↓ Histidine (HPV+/Lesions) |

| Daí et al., 2024 [70] | China | Prospective study | Multi- omics | 65 | 0 | 65 | YES | ↑ Prevotella, Streptococcus ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↑ Glycerophospholipids (MetaG10); ↓ Amino acids and peptides (MetaG1, MetaG5) after HPV+ CIN treatment |

| Zheng et al., 2020 [71] | China | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 532 | 154 | 378 | YES | ↑ BV, VVC, TV; ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↑ Sialidase, ↑ GUS (HPV+) |

| Wang et al., 2017 [72] | China | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 531 | 176 | 363 | YES | ↑ BV-associated microecology; ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↓ H2O2, ↑ SNA, ↑ LE, ↑ GUS, ↑ GADP (associated with CIN and persistent HPV infection) |

| Zhang et al., 2022 [73] | China | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 420 | 140 | 280 | NR | ↑ BV, VVC, TV; ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↓ H2O2, ↑ Sialidase, ↑ LE (HPV+) |

| Tao et al., 2023 [74] | China | Cross sectional | Non-omics | 169 | 0 | 169 | YES | ↑ BV-associated profile; ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↑ LE, ↓ SNA, ↓ H2O2, (HPV+ improvement after focused ultrasound) |

| Shi et al., 2024 [75] | China | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 11.540 | 8.043 | 3 | YES | ↑ BV-associated microecology ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↓ H2O2, ↑ LE (CIN) |

| Dasari et al., 2014 [76] | India | Case control | Non- omics | 109 | NR | 19 | YES | ↑ BV, Trichomonas vaginalis, Candida spp.; ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↑ Mucinase, ↑ Sialidase, ↑ Protease (CIN III/NCIS/ICC) |

| Dai et al., 2025 [77] | China | Cross sectional | Multi-omics | 43 | 0 | 43 | YES | ↑ Gardnerella, Atopobium, Sneathia, Dialister ↓ Lactobacillus crispatus | ↑ Capric acid, ↑Oleic acid, ↑ Inosine, ↑ DL.3 (4-hydroxyphenyl)lactic acid; ↓ Lactate (LSIL/HSIL/HPV+) |

| Sun et al., 2023 [78] | China | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 512 | 300 | 300 | YES | ↑ G. vaginalis, yeasts (Candida spp.); ↓ L. acidophilus | ↑ Proline aminopeptidase, ↑ LE, ↑ Catalase (HPV+) |

| Liu et al., 2024 [79] | China | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 2.000 | 1.759 | 241 | NR | ↑ BV, AV (aerobic vaginitis); ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↑GUS; ↑ SNA, ↑ LE (HPV+) |

| Li et al., 2020 [80] | China | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 1.019 | 839 | 180 | YES | ↑ BV-associated profile ↓ Lactobacillus spp. | ↓ H2O2, ↑ GUS, ↑ SNA, ↑ LE (HPV16+/CIN) |

| Lu et al., 2021 [81] | China | Cross sectional and clinical trial | Non-omics | 276 | 120 | 156 | YES | ↑ BV-associated profile); ↓ Lactobacillus spp. (inferred) | ↓ H2O2, ↑ GUS, ↑ acetilglucosaminidase, ↑ SNA (CIN/HPV+) |

| Venancio et al., 2019 [82] | Brazil | Experimental in vitro/vivo | Non-omics | 165 | 96 | 69 | YES | Gram-stained bacterioscopy indicates presence of BV, Candida spp., and Actinomyces in HPV+ samples | ↑ IDO (squamous cells, leukocytes—HPV+ HSIL/CC); ↑ TDO (stromal leukocytes—HPV16+) |

| Qulu et al., 2023 [83] | South Africa. | Cross sectional | Non-omics | 243 | 160 | 83 | NR | ↑ BV-associated profile; ↓ Lactobacillus spp. (inferred) | ↑ MMP-10 (CIN) |

| Choi et al., 2006 [84] | Korea | Cross sectional | Non- omics | 1.138 | 54 | 96 | YES | No significant association between Lactobacillus spp. and HPV+ | None (no significant association with HPV or lesions) |

| Total/Summary | NA | NA | NA | 31,494 | 20,383 | 9299 | 7582 (CIN I: 1860; CINII/III:1918; CIS:28; CC:325 | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Machado, E.P.; Junkert, A.M.; Lazo, R.E.L.; Fernandes, I.d.C.; Tonin, F.S.; Ferreira, L.M.; Borba, H.H.L.; Pontarolo, R. Mapping the Vaginal Metabolic Profile in Dysbiosis, Persistent Human Papillomavirus Infection, and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010042

Machado EP, Junkert AM, Lazo REL, Fernandes IdC, Tonin FS, Ferreira LM, Borba HHL, Pontarolo R. Mapping the Vaginal Metabolic Profile in Dysbiosis, Persistent Human Papillomavirus Infection, and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleMachado, Ednéia Peres, Allan Michael Junkert, Raul Edison Luna Lazo, Idonilton da Conceição Fernandes, Fernanda Stumpf Tonin, Luana Mota Ferreira, Helena Hiemisch Lobo Borba, and Roberto Pontarolo. 2026. "Mapping the Vaginal Metabolic Profile in Dysbiosis, Persistent Human Papillomavirus Infection, and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Scoping Review" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010042

APA StyleMachado, E. P., Junkert, A. M., Lazo, R. E. L., Fernandes, I. d. C., Tonin, F. S., Ferreira, L. M., Borba, H. H. L., & Pontarolo, R. (2026). Mapping the Vaginal Metabolic Profile in Dysbiosis, Persistent Human Papillomavirus Infection, and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010042