UHPLC–Q–Orbitrap–HRMS-Based Multilayer Mapping of the Pharmacodynamic Substance Basis and Mechanistic Landscape of Maizibizi Wan in Chronic Nonbacterial Prostatitis Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

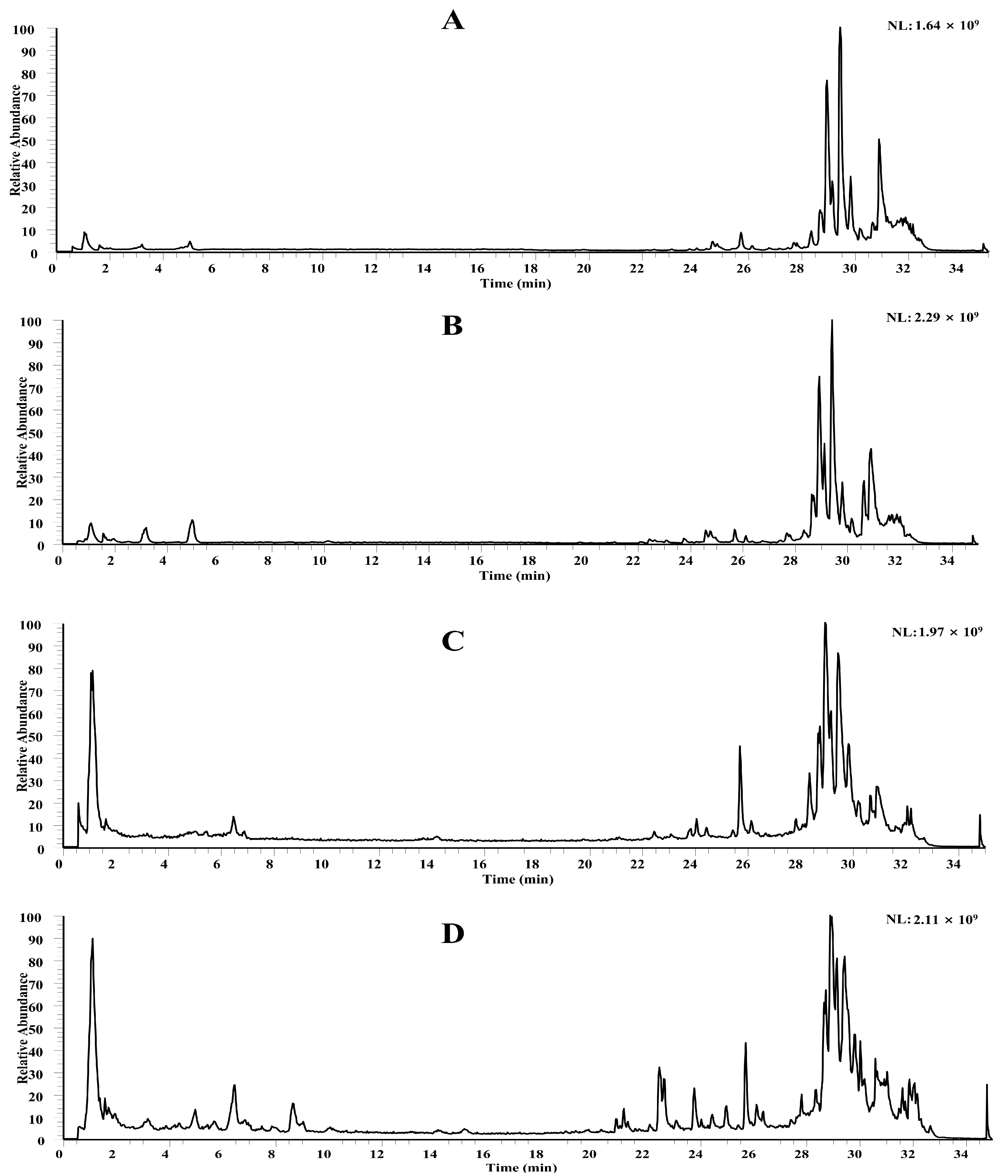

2.1. Chemical Profiling of MZBZ Based on LC-MS

2.1.1. Flavonoids

2.1.2. Organic Acids

2.1.3. Alkaloids

2.1.4. Other Compounds

2.2. Plasma-Exposed Prototypes and Metabolites

2.3. Network Pharmacology Highlights

2.3.1. Prediction of Targets for Blood-Absorbable Prototype Components of MZBZ

2.3.2. GO Functional and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Potential Targets for MZBZ Blood-Absorbable Prototype Components

2.3.3. Construction of the “MZBZ-Components-Disease-Targets-Pathways” Network

2.4. Docking of Key Components to Core Targets

2.5. In Vivo Validation

2.5.1. Effects of MZBZ on Pathological Changes in the CNP Rat Model

2.5.2. Effects of MZBZ on Changes in Serum Inflammatory Factors in CNP Rats

2.5.3. Effects of MZBZ on the Expression of Key Targets in Prostate Tissue

2.5.4. Effects of MZBZ on Proteomic Changes in Prostate Tissue of the Nonbacterial Prostatitis Rat Model

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals, Reagents, and Instruments

4.2. Ethics

4.3. Preparation of MZBZ and Reference Solutions

4.4. Serum Pharmacochemistry

4.4.1. Drug-Containing Serum

4.4.2. Plasma Processing

4.5. UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap-HRMS

4.6. Data Processing and GNPS

4.7. Network Pharmacology

4.7.1. Predicting Putative Anti-Inflammatory Targets

4.7.2. Network Construction and Enrichment Analysis

4.8. Molecular Docking

4.9. Experimental Validation

4.9.1. CNP Model and Treatment

4.9.2. Sample Collection and Histology

4.9.3. Immunohistochemistry

4.9.4. Cytokines and Western Blot

4.10. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKT | RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase. |

| BCL2 | B-cell lymphoma-2. |

| CP | Chronic prostatitis. |

| CNP | Chronic nonbacterial prostatitis. |

| COX2 | Cyclooxygenase-2. |

| ED | Erectile dysfunction. |

| GNPS | Global natural products social molecular networking. |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6. |

| IL-17 | Interleukin-17. |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. |

| MZBZ | Maizibizi Wan. |

| MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9. |

| NFK-B | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells. |

| TNF-a | Tumar necrosis factor a. |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor-beta 1. |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese medicine. |

References

- Magistro, G.; Wagenlehner, F.M.; Grabe, M.; Weidner, W.; Stief, C.G.; Nickel, J.C. Contemporary Management of Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontari, M.A. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in elderly men: Toward better understanding and treatment. Drugs Aging 2003, 20, 1111–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, J.N.; Lee, S.W.H.; Jeon, J.; Cheah, P.Y.; Liong, M.L.; Riley, D.E. Epidemiology of prostatitis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2008, 31, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, J.O.H.N.N.; Ross, S.U.S.A.N.O.; Riley, D.O.N.A.L.D.E. Chronic prostatitis: Epidemiology and role of infection. Urology 2002, 60, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.Z.; Li, H.J.; Wang, Z.P.; Xing, J.P.; Hu, W.L.; Zhang, T.F.; Ge, W.W.; Hao, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.S.; Zhou, J.; et al. The prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in China. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of Ningmitai capsule on the treatment of chronic prostatitis in China. Medicine 2018, 97, e11840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yu, Q.; Wu, C.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, H.; Liao, M.; Li, T.; Chen, W.; et al. The prevalence of and risk factors for prostatitis-like symptoms and its relation to erectile dysfunction in Chinese men. Andrology 2015, 3, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, J.N. Classification, epidemiology and implications of chronic prostatitis in North America, Europe and Asia. Minerva Urol. E Nefrol. Ital. J. Urol. Nephrol. 2004, 56, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cyril, A.C.; Jan, R.K.; Radhakrishnan, R. Pain in chronic prostatitis and the role of ion channels: A brief overview. Br. J. Pain 2022, 16, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhong, W.; Luo, R.; Wen, H.; Ma, Z.; Qi, S.; Han, X.; Nie, W.; Chang, D.; Xu, R.; et al. Thermosensitive hydrogel with emodin-loaded triple-targeted nanoparticles for a rectal drug delivery system in the treatment of chronic non-bacterial prostatitis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.H.; Han, J.P.; Feng, J.Y.; Guo, K.; Du, F.; Chen, W.B.; Li, Y.Z. Dihydroartemisinin ameliorates chronic nonbacterial prostatitis and epithelial cellular inflammation by blocking the E2F7/HIF1α pathway. Inflamm. Res. Off. J. Eur. Histamine Res. Soc. 2022, 71, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontari, M.A. Etiologic theories of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2007, 8, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, J.V.; Turk, T.; Jung, J.H.; Xiao, Y.T.; Iakhno, S.; Tirapegui, F.I.; Garrote, V.; Vietto, V. Pharmacological interventions for treating chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, Cd012552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadtursun, N.; Paierhati, A.; Maihemuti, M.; Abulati, R.; Mutailifu, P.; Nuermaimaiti, M. Identification of Chemical Components of Maizibizi Wan and Study on its Mechanism of Intervention in a Rat Model of Non-Bacterial Prostatitis. Chin. J. Androl. 2025, 39, 10–23+56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tuerdi, W.; Maitusun, N.; Nasier, W.; Tuoheti, K.; DONG, J. Study of Maizibizi Wan on Non-Bacterial Prostatitis in Rats. Pharmacol. Clin. Chin. Mater. Medica 2017, 33, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bai, Q.X.; Zheng, X.X.; Hu, W.J.; Wang, S.; Tang, H.P.; Yu, A.Q.; Yang, B.Y.; Kuang, H.X. Smilax china L.: A review of its botany, ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, actual and potential applications. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 318, 116992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.Y.; Wei, B.Y.; Ma, J.Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.Y. Phytochemicals, Biological Activities, Molecular Mechanisms, and Future Prospects of Plantago asiatica L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 143–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbrouck, J.A.; Desgagné, M.; Comeau, C.; Bouarab, K.; Malouin, F.; Boudreault, P.L. The Therapeutic Value of Solanum Steroidal (Glyco)Alkaloids: A 10-Year Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Yu, D.; Tian, B.; Li, W.; Sun, Z. Research progress on the chemical components and pharmacological effects of Physalis alkekengi L. var. franchetii (Mast.) Makino. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bai, L.; Yi, K.; Pan, X. Research progress on chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Physalis alkekengi L.var. franchetii (Mast.) Makino. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2022, 34, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.D.; Hu, C.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Zhang, L.C. Main chemical constituents and mechanism of anti-tumor action of Solanum nigrum L. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, M.; Khan, M.S.; Amir, K.; Bi, J.B.; Asif, M.; Madni, A.; Kamboh, A.A.; Manzoor, Z.; Younas, U.; Chao, S. Lagenaria siceraria fruit: A review of its phytochemistry, pharmacology, and promising traditional uses. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 927361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabeza, M. Current Understanding of Androgen Signaling in Prostatitis and its Treatment: A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 4249–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, A.Q.; Yue, S.Y.; Niu, D.; Zhang, D.D.; Hou, B.B.; Zhang, L.; Liang, C.Z.; Du, H.X. The role of microbiota in the chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvis pain syndrome: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1488732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Yue, S.; Zhang, C.; Song, J.; Liang, H.; Liang, C.; Chen, X. NLRP3-mediated IL-1β in regulating the imbalance between Th17 and Treg in experimental autoimmune prostatitis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitomi, Y.; Nakamura, M. The Genetics of Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A GWAS and Post-GWAS Update. Genes 2023, 14, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Martín, M.I.; Sanchiz, Á.; Navasa, N. Interplay between the host genome, autoimmune disease and infection. Adv. Genet. 2025, 114, 101–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoc, E.M.; Villain, C.; Chrétien, B.; Benbrika, S.; Heraudeau, M.; Lafont, C.; Béchade, C.; Lobbedez, T.; Lelong-Boulouard, V.; Dolladille, C. Association between antidepressant drugs and falls in older adults: A mediation analysis in the World Health Organization’s pharmacovigilance database. Therapie 2025, 80, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Greenland, J.C.; Williams-Gray, C.H. Clinical Trial Highlights: Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Agents. J. Park. Dis. 2024, 14, 1283–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Ka, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, W. Research progress on pharmacokinetics, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of kaempferol. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 152, 114387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sharma, R.; Garg, N. Withania somnifera—A magic plant targeting multiple pathways in cancer related inflammation. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2022, 101, 154137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kian, M.; Mirzavand, S.; Sharifzadeh, S.; Kalantari, T.; Ashrafmansouri, M.; Nasri, F. Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Therapy in Parasitic Infections: Are Anti-parasitic Drugs Combined with MSCs More Effective? Acta Parasitol. 2022, 67, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.H.; Wu, C.S.; Chiou, S.H.; Chang, C.H.; Liao, H.J. Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Exosomes as a Novel Anti-Inflammatory Agent and the Current Therapeutic Targets for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efeoglu, C.; Taskin, S.; Selcuk, O.; Celik, B.; Tumkaya, E.; Ece, A.; Sari, H.; Seferoglu, Z.; Ayaz, F.; Nural, Y. Synthesis, anti-inflammatory activity, inverse molecular docking, and acid dissociation constants of new naphthoquinone-thiazole hybrids. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2023, 95, 117510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.K.; Raja, S.; Mahapatra, S.; Nagabhushanam, K.; Majeed, M. Synthesis and Evaluation of the Anti-Oxidant Capacity of Curcumin Glucuronides, the Major Curcumin Metabolites. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 750–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, U.M.; Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, S.; Gao, R. Isorhamnetin inhibited the proliferation and metastasis of androgen-independent prostate cancer cells by targeting the mitochondrion-dependent intrinsic apoptotic and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20192826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, D.; Zhou, G.; Li, J.; Su, B.; Guo, H. Ursolic acid activates the apoptosis of prostate cancer via ROCK/PTEN mediated mitochondrial translocation of cofilin-1. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 3202–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiki, T.; Naiki-Ito, A.; Murakami, A.; Kato, H.; Sugiyama, Y.; Kawai, T.; Kato, S.; Etani, T.; Nagai, T.; Shimizu, N.; et al. Preliminary Evidence on Safety and Clinical Efficacy of Luteolin for Patients With Prostate Cancer Under Active Surveillance. Prostate Cancer 2025, 2025, 8165686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryilmaz, I.E.; Colakoglu Bergel, C.; Arioz, B.; Huriyet, N.; Cecener, G.; Egeli, U. Luteolin induces oxidative stress and apoptosis via dysregulating the cytoprotective Nrf2-Keap1-Cul3 redox signaling in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 52, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Esquivias, F.; Guzmán-Flores, J.M.; Pech-Santiago, E.O.; Guerrero-Barrera, A.L.; Delgadillo-Aguirre, C.K.; Anaya-Esparza, L.M. Therapeutic Role of Quercetin in Prostate Cancer: A Study of Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Dynamics Simulation. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 83, 3153–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.F.; Schaeffer, A.J.; Done, J.; Wong, L.; Bell-Cohn, A.; Roman, K.; Cashy, J.; Ohlhausen, M.; Thumbikat, P. IL17 Mediates Pelvic Pain in Experimental Autoimmune Prostatitis (EAP). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Q.J.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wang, Y.M.; Zhu, G.Q.; Song, N.H.; Wang, Z.J.; Chen, J.H.; Xia, J.D. Upregulated expression of NMDA receptor in the paraventricular nucleus shortens ejaculation latency in rats with experimental autoimmune prostatitis. Andrology 2021, 9, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Feng, R.; Meng, T.; Peng, W.; Song, J.; Ma, W.; Xu, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; et al. CXCR4 regulates macrophage M1 polarization by altering glycolysis to promote prostate fibrosis. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2024, 22, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Identification | tR/min | MS Fragment | m/z | Formula | Ion Type | Error/ppm | Classification | Resource |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gluconic acid | 0.96 | 177(5), 129(29), 75(100) | 195.0511 | C6H12O7 | [M−H]− | 0.46 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 2 | Proline | 1.01 | 87(3), 70(100) | 116.0707 | C5H9NO2 | [M+H]+ | 0.26 | Other | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 3 | Citric acid | 1.09 | 111(100), 87(56), 85(32), 57(9) | 191.0201 | C6H8O7 | [M−H]− | 1.45 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 4 | Malic acid | 1.17 | 115(19), 85(43), 71(56) | 133.0142 | C4H6O5 | [M−H]− | 1.75 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 5 | Methylmalonic acid or isomer | 1.70 | 73(100) | 117.0196 | C4H6O4 | [M−H]− | 1.75 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 6 | Galloyl hexoside | 2.00 | 169(100), 125(62) | 331.0679 | C13H16O10 | [M−H]− | 4.07 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 7 | Furoic acid | 2.33 | 67(81) | 111.0091 | C5H4O3 | [M−H]− | 2.03 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 8 | Citric acid methyl ester | 2.34 | 143(10), 111(100), 87(47) | 205.0357 | C7H10O7 | [M−H]− | 1.38 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 9 | Dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside or isomer | 2.67 | 153(100), 109(7) | 315.0731 | C13H16O9 | [M−H]− | 4.22 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 10 | Phenylalanine | 2.97 | 149(3), 120(100), 103(10) | 166.0862 | C9H11NO2 | [M+H]+ | 1.11 | Alkaloid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 11 | Methylmalonic acid or isomer | 3.30 | 87(100) | 131.0352 | C5H8O4 | [M−H]− | 2.36 | Organic acid | [16,17] |

| 12 | Protocatechuic acid | 3.39 | 109(13) | 153.0197 | C7H6O4 | [M−H]− | 2.28 | Organic acid | [16,17] |

| 13 | Dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside or isomer | 3.45 | 153(100), 109(64) | 315.0725 | C13H16O9 | [M−H]− | 4.41 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 14 | Vanillic acid | 3.80 | 152(100), 123(26), 108(48) | 167.0353 | C8H8O4 | [M−H]− | 0.29 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 15 | Geniposidic acid | 3.90 | 211(32), 193(8), 167(22), 149(51), 123(100) | 373.1135 | C16H22O10 | [M−H]− | −0.26 | Organic acid | [16,17] |

| 16 | Gentisic acid | 4.08 | 109(100) | 153.0197 | C7H6O4 | [M−H]− | 0.7 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 17 | Kojic acid | 4.45 | 97(3), 69(10) | 143.0338 | C6H6O4 | [M+H]+ | −1.47 | Organic acid | [16,20] |

| 18 | Caffeoylquinic acid–hexoside or isomer | 4.52 | 353(16), 191(100), 179(13), 135(14) | 515.1422 | C22H28O14 | [M−H]− | 2.24 | Organic acid | [20] |

| 19 | Tryptophan | 4.85 | 188(100), 146(95), 144(21), 132(10), 118(41) | 205.0968 | C11H11NO2 | [M+H]+ | −1.52 | Other | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 20 | caffeoylquinic acid–hexoside or isomer | 5.59 | 353(12), 191(100), 179(10), 135(12) | 515.1414 | C22H28O14 | [M−H]− | 3.66 | Organic acid | [20,21] |

| 21 | Ferulic acid–hexoside or isomer | 5.87 | 193(100), 178(13), 149(23), 134(80) | 355.1042 | C16H20O9 | [M−H]− | 3.24 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 22 | Caffeoylquinic acid–hexoside or isomer | 6.14 | 353(12), 191(100), 179(16), 135(20) | 515.1415 | C22H28O14 | [M−H]− | 2.47 | Organic acid | [20,21] |

| 23 | Scopoletin | 6.29 | 178(21), 133(34) | 193.0492 | C10H8O4 | [M+H]+ | −2.04 | Phenylpropanoids | [20] |

| 24 | Methylquinoline | 6.39 | 117(4), 103(3) | 144.0806 | C9H8NO | [M+H]+ | −1.57 | Alkaloid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 25 | Solanigrine A or isomer | 6.50 | 930(27), 912(100), 894(12), 85(12) | 930.4670 | C45H71NO19 | [M+H]+ | −2.44 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 26 | Quercetin–dihexoside or isomer | 6.62 | 463(43), 301(38), 299(100), 271(47), 243(5), 151(7), 121(6) | 625.1420 | C27H30O17 | [M−H]− | 1.23 | Flavonoid | [20] |

| 27 | Vanillin or isomer | 6.62 | 136(2), 109(19) | 151.0404 | C8H8O3 | [M−H]− | 0.22 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 28 | Procyanidin B2 | 6.73 | 577(5), 451(10), 425(17), 407(46), 289(67), 255(7), 161(22), 125(100) | 577.1362 | C30H26O12 | [M−H]− | 1.54 | Flavonoid | [16] |

| 29 | Esculetin | 6.79 | 149(4), 133(27), 105(15), 89(2) | 177.0194 | C9H6O4 | [M−H]− | 0.19 | Phenylpropanoids | [16,17,18,19,20]. |

| 30 | CQA–hexoside or isomer | 7.06 | 353(4), 191(100), 179(4), 135(3) | 515.1416 | C22H28O14 | [M−H]− | 4.02 | Organic acid | [20,21] |

| 31 | Ferulic acid–hexoside or isomer | 7.17 | 193(100), 178(33), 149(16), 134(55) | 355.1039 | C16H20O9 | [M−H]− | 2.75 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 32 | Sibiricose A1 | 7.37 | 323(3), 285(13), 223(100), 205(93), 190(88), 175(26), 164(19), 149(23) | 547.1679 | C23H32O15 | [M−H]− | 1.83 | Other | [20] |

| 33 | Cryptochlorogenic acid | 7.37 | 191(52), 179(67), 173(100), 135(71), 93(27), 85(9) | 353.0882 | C16H18O9 | [M−H]− | 0.92 | Organic acid | [20,21] |

| 34 | Pyranamide C | 7.44 | 472(100), 310(15), 220(37), 163(54), 145(5) | 472.2431 | C25H33N3O6 | [M+H]+ | −0.75 | Alkaloid | [20] |

| 35 | Syringic acid | 7.44 | 155(19), 140(100), 125(12) | 197.0459 | C9H10O5 | [M−H]− | 1.16 | Organic acid | [16] |

| 36 | Kaempferol 3-(2G-glucosylrutinnoside)-7-glucoside | 7.70 | 917(8), 771(100), 429(5), 285(23), 284(47), 255(37), 227(15), 151(5) | 917.2592 | C39H50O25 | [M−H]− | 2.59 | Flavonoid | [21,22] |

| 37 | Quercetin 3-(2G-glucosylrutinoside) | 7.74 | 771(95), 300(100), 271(66), 255(37), 243(14), 179(5), 151(7) | 771.2006 | C33H40O21 | [M−H]− | 1.93 | Flavonoid | [17,21] |

| 38 | Okanin–dihexose or isomer | 8.22 | 611(5), 449(75), 287(82), 151(100), 135(53), 107(18) | 611.1630 | C27H32O16 | [M−H]− | 1.97 | Flavonoid | [20] |

| 39 | Parmosidone G | 8.27 | 473(3), 411(36), 381(20), 351(45), 309(54), 163(44), 145(100), 119(36) | 507.1281 | C27H24O10 | [M−H]− | −3.06 | Other | [21] |

| 40 | Theogallin | 8.36 | 343(5), 281(3), 197(14), 145(100), 119(67) | 343.0677 | C14H16O10 | [M−H]− | 1.89 | Organic acid | [16] |

| 41 | Cinchonain IIa | 8.38 | 739(41), 587(32), 449(21), 435(10), 339(30), 289(51), 177(100), 161(24), 137(27) | 739.1690 | C39H32O15 | [M−H]− | 2.84 | Other | [16] |

| 42 | Luteolin–dihexoside or isomer | 8.52 | 447(100), 285(90), 284(37), 151(2), 133(2) | 609.1473 | C27H30O16 | [M−H]− | 3.72 | Flavonoid | [20] |

| 43 | Apigenin–dihexoside | 8.53 | 595(5), 433(31), 271(100), 153(4) | 595.1643 | C27H30O15 | [M+H]+ | −2.53 | Flavonoid | [20] |

| 44 | Taxifolin–hexoside or isomer | 8.56 | 465(70), 303(77), 285(75), 179(15), 151(14), 125(100) | 465.1046 | C21H22O12 | [M−H]− | 1.71 | Flavonoid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 45 | Feruloylquinic acid or isomer | 8.62 | 191(100), 173(10), 134(12), 93(29) | 367.1041 | C17H20O9 | [M−H]− | 3.32 | Organic acid | [20,21] |

| 46 | Vanillin or isomer | 8.73 | 136(100), 108(7) | 151.0403 | C8H8O3 | [M−H]− | 0.29 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 47 | Quercetin–dihexoside or isomer | 8.80 | 463(100), 301(84), 300(66), 299(7), 271(34), 255(13), 243(5), 151(23) | 625.1421 | C27H30O17 | [M−H]− | 3.46 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 48 | Alternatain D | 8.93 | 319(25), 233(73), 173(42), 163(21), 145(32), 119(24) | 379.1043 | C18H20O9 | [M−H]− | 2.25 | Other | [21] |

| 49 | Kaempferol–dihexoside or isomer | 9.01 | 447(9), 285(16), 284(20), 283(94), 255(49), 151(4) | 609.1476 | C27H30O16 | [M−H]− | 4.22 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 50 | Solanigrine A or isomer | 9.02 | 930(100), 912(12), 894(13), 85(10) | 930.4671 | C45H71NO19 | [M+H]+ | −2.37 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 51 | Okanin–dihexose or isomer | 9.24 | 449(80), 287(68), 151(100), 135(71), 107(15) | 611.1628 | C27H32O16 | [M−H]− | 1.67 | Flavonoid | [20] |

| 52 | Quercetin–dihexoside or isomer | 9.36 | 303(100), 229(4), 127(2) | 627.1539 | C27H30O17 | [M+H]+ | −2.72 | Flavonoid | [21,22] |

| 53 | Solanigroside Q or isomer | 9.46 | 916(100), 898(15), 880(6), 85(13) | 916.4881 | C45H73NO18 | [M+H]+ | −2.12 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 54 | Taxifolin or isomer | 9.56 | 305(99), 287(29), 259(77), 231(58), 213(11), 153(100), 149(72), 123(67) | 305.0649 | C15H12O7 | [M+H]+ | −2.2 | Flavonoid | [16] |

| 55 | Plantagoside | 9.59 | 465(100), 303(68), 297(51), 166(54), 153(51), 135(82) | 465.1046 | C21H22O12 | [M−H]− | 1.64 | Flavonoid | [16,17,21,22] |

| 56 | Suberic acid | 9.67 | 111(100), 83(13) | 173.0821 | C8H14O4 | [M−H]− | 1.04 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 57 | Rimocidin | 9.71 | 768(100), 750(14), 732(18), 85(10) | 768.4151 | C39H61NO14 | [M+H]+ | −1.8 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 58 | Solanigrine A or isomer | 9.71 | 930(100), 912(12), 894(11), 85(12) | 930.4673 | C45H71NO19 | [M+H]+ | −2.17 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 59 | Quercetin–deoxyhexosie–hexoside or isomer | 9.74 | 301(18), 300(100), 271(50), 179(2), 151(6) | 609.1473 | C27H30O16 | [M−H]− | 3.82 | Flavonoid | [19,21] |

| 60 | Feruloylquinic acid or isomer | 9.91 | 191(100), 173(10), 135(100) | 367.104 | C17H20O9 | [M−H]− | 3.47 | Organic acid | [19,21] |

| 61 | Cinchonain IIb | 9.96 | 739(25), 587(30), 449(17), 435(12), 339(32), 289(43), 177(100), 161(26), 137(18) | 739.1684 | C39H32O15 | [M−H]− | 1.88 | Other | [16] |

| 62 | Kaempferol–dihexoside or isomer | 10.01 | 609(15), 447(95), 285(100), 284(28), 255(8), 151(2), 133(3) | 609.1469 | C27H30O16 | [M−H]− | 0.94 | Flavonoid | [19,20,21] |

| 63 | Luteolin–dihexoside or isomer | 10.04 | 447(100), 285(100), 284(27), 255(8), 151(3), 133(2) | 609.1468 | C27H30O16 | [M−H]− | 2.12 | Flavonoid | [20] |

| 64 | Solanigroside Q or isomer | 10.10 | 916(100), 898(14), 880(17), 85(8) | 916.4885 | C45H73NO18 | [M+H]+ | −1.71 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 65 | Solanigrine A or isomer | 10.31 | 930(100), 912(22), 894(10), 85(14) | 930.4667 | C45H71NO19 | [M+H]+ | −2.83 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 66 | Isovitexin 2″-O-feruloyl-glucoside-4′-O-glucoside | 10.44 | 929(14), 769(75), 315(100), 314(49), 300(32), 299(30), 271(22), 243(12) | 931.2543 | C43H48O23 | [M−H]− | 3.19 | Flavonoid | [21] |

| 67 | Taxifolin–hexoside or isomer | 10.49 | 465(46), 303(24), 151(100), 107(12) | 465.1044 | C21H22O12 | [M−H]− | 1.17 | Flavonoid | [20] |

| 68 | Ferulic acid or isomer | 10.52 | 178(66), 149(23), 134(100) | 193.0509 | C10H10O4 | [M−H]− | 0.76 | Organic acid | [20,22] |

| 69 | Feruloyloctopamine or isomer | 10.55 | 328(6), 311(19), 310(100), 161(91), 133(61) | 328.1198 | C18H19NO5 | [M−H]− | 2.42 | Alkaloid | [20,21] |

| 70 | Kaempferol–dihexoside or isomer | 10.56 | 447(100), 285(44), 284(67), 255(52), 227(29), 151(5) | 609.1475 | C27H30O16 | [M−H]− | 4.12 | Flavonoid | [21] |

| 71 | Sophoraflavonloside | 10.58 | 609(100), 447(10), 285(39), 284(60), 255(50), 227(29), 151(5), 135(3) | 609.1476 | C27H30O16 | [M−H]− | 2.17 | Flavonoid | [20,21] |

| 72 | Luteolin-7-O-glucoside | 10.59 | 285(100), 284(59), 151(5), 133(9) | 447.0942 | C21H20O11 | [M−H]− | 4.51 | Flavonoid | [16,22] |

| 73 | Solanigroside Q or isomer | 10.71 | 916(100), 898(12), 880(17), 85(7) | 916.4883 | C45H73NO18 | [M+H]+ | −1.86 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 74 | Coumaric acid hexoside or isomer | 10.84 | 163(100), 135(17), 117(7), 97(14) | 325.0908 | C15H16O7 | [M+H]+ | −2.24 | Phenylpropanoids | [20] |

| 75 | Quercetin-deoxyhexosie–hexoside or isomer | 10.86 | 301(41), 300(74), 271(39), 179(4), 151(19) | 609.1472 | C27H30O16 | [M−H]− | 3.62 | Flavonoid | [21,22] |

| 76 | Solanigrine B or isomer | 10.91 | 914(100), 897(6), 896(12), 878(13), 85(12) | 914.4734 | C45H71NO18 | [M+H]+ | −1.1 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 77 | Plantamajoside isomer | 10.96 | 639(44), 477(16), 179(2), 161(100), 135(12), 133(26) | 639.1940 | C29H36O16 | [M−H]− | 1.42 | Phenylethanoid glycoside | [20] |

| 78 | Sinaticin | 11.14 | 435(21), 393(11), 325(62), 313(62), 283(14), 163(29), 123(100) | 435.1064 | C24H18O8 | [M+H]+ | −2.37 | Flavonoid | [16] |

| 79 | Rutin | 11.20 | 609(100), 301(36), 300(77), 271(48), 255(23), 243(8), 179(5), 151(12), 107(4) | 609.1472 | C27H30O16 | [M−H]− | 1.54 | Flavonoid | [19] |

| 80 | Solanigrine B or isomer | 11.29 | 914(100), 897(5), 896(13), 878(13), 85(10) | 914.4726 | C45H71NO18 | [M+H]+ | −1.97 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 81 | Sinensin | 11.33 | 341(36), 287(87), 217(11), 189(19), 151(100), 135(71), 107(15) | 449.1095 | C21H22O11 | [M−H]− | 1.09 | Flavonoid | [19,20] |

| 82 | Solanigrine D or isomer | 11.34 | 754(100), 736(15), 718(19), 85(8) | 754.4364 | C39H63NO13 | [M+H]+ | −1.08 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 83 | Hyperoside | 11.38 | 301(100), 300(20), 271(2), 255(2), 151(32), 107(9) | 463.0891 | C21H20O12 | [M−H]− | 4.27 | Flavonoid | [20,22] |

| 84 | Ferulic acid or isomer | 11.41 | 178(26), 149(11), 134(100) | 193.0508 | C10H10O4 | [M−H]− | 1.08 | Organic acid | [19,21] |

| 85 | Procyanidin B4 | 11.49 | 577(7), 451(11), 425(17), 407(37), 289(49), 161(23), 151(10), 125(100) | 577.1361 | C30H26O12 | [M−H]− | 1.29 | Flavonoid | [16] |

| 86 | Solanigroside Q or isomer | 11.50 | 916(100), 898(3), 85(15) | 916.4872 | C45H73NO18 | [M+H]+ | −3.12 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 87 | Astilbin or isomer | 11.55 | 303(18), 285(40), 179(20), 151(100), 125(24), 107(20) | 449.1095 | C21H22O11 | [M−H]− | 3.62 | Flavonoid | [16] |

| 88 | Isorhamnetin–dihexoside | 11.68 | 639(100), 315(36), 314(31), 300(19), 299(33), 285(6), 271(26), 255(10), 243(20), 151(3) | 639.1580 | C28H32O17 | [M−H]− | 1.77 | Flavonoid | [21] |

| 89 | Sinapinic acid | 11.73 | 208(36), 193(26), 164(56), 149(100), 121(32) | 223.0615 | C11H12O5 | [M−H]− | 1.41 | Organic acid | [21] |

| 90 | Quercetin–hexoside or isomer | 11.89 | 463(69), 301(53), 300(100), 271(70), 255(31), 243(15), 179(5), 151(21) | 463.0894 | C21H20O12 | [M−H]− | 2.15 | Flavonoid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 91 | Luteolin–dihexoside or isomer | 11.89 | 447(2), 285(100), 284(12), 151(4), 133(4) | 609.1464 | C27H30O16 | [M−H]− | 2.31 | Flavonoid | [19] |

| 92 | Luteolin–pentoside–hexoside | 12.03 | 285(77), 284(38), 151(4), 133(3) | 579.1368 | C26H28O15 | [M−H]− | 1.01 | Flavonoid | [19,22] |

| 93 | Quercetagetin 7-methyl ether 3-neohesperidoside | 12.09 | 639(86), 315(100), 314(24), 300(34), 299(29), 285(6), 271(40), 255(15), 243(20), 227(5) | 639.1581 | C28H32O17 | [M−H]− | 2.05 | Flavonoid | [16,21] |

| 94 | Astilbin or isomer | 12.13 | 303(14), 285(86), 179(14), 151(100), 125(20), 107(18) | 449.1091 | C21H22O11 | [M−H]− | 2.87 | Flavonoid | [16,22] |

| 95 | Luteolin–hexoside | 12.17 | 285(100), 284(39), 179(9), 151(65), 133(4) | 447.0936 | C21H20O11 | [M−H]− | 3.22 | Flavonoid | [19,20] |

| 96 | Coumaric acid hexoside or isomer | 12.52 | 163(100), 135(16), 117(7), 97(16) | 325.0909 | C15H16O7 | [M+H]+ | −2.53 | Phenylpropanoids | [20] |

| 97 | Feruloyloctopamine or isomer | 12.54 | 328(4), 311(19), 310(100), 161(89), 133(63) | 328.1196 | C18H19NO5 | [M−H]− | 1.53 | Alkaloid | [20,21] |

| 98 | Luteolin–dexoyhexoside–hexoside | 12.64 | 447(2), 285(63), 284(44), 151(3), 133(3) | 593.1522 | C27H30O15 | [M−H]− | 3.48 | Flavonoid | [20] |

| 99 | Isoacteoside | 12.73 | 461(9), 179(3), 161(100), 133(31), 113(12) | 623.1995 | C29H36O15 | [M−H]− | 2.21 | Phenylpropanoids | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 100 | Hydroxybenzoic acid | 12.82 | 93(100) | 137.0247 | C7H6O3 | [M−H]− | 2.08 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 101 | Solanigrine K | 13.14 | 940(7), 899(43), 898(100), 753(19), 752(52), 163(10), 113(15), 101(19) | 940.4922 | C47H75NO18 | [M−H]− | 1.12 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 102 | Solanigrine D or isomer | 13.14 | 754(100), 736(15), 718(19), 85(9) | 754.4358 | C39H63NO13 | [M+H]+ | −1.89 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 103 | Plantamajoside isomer | 13.18 | 639(49), 447(27), 179(30), 161(100), 135(22), 133(34) | 639.1942 | C29H36O16 | [M−H]− | 1.81 | Phenylethanoid glycoside | [20] |

| 104 | 3, 4-dimethoxyphenyl-acrylamide | 13.27 | 344(5), 177(100), 151(7), 145(41), 117(17) | 344.1484 | C19H21NO5 | [M+H]+ | −2.63 | Alkaloid | [20] |

| 105 | Verbascoside | 13.60 | 461(6), 179(2), 161(100), 133(30), 113(12) | 623.1990 | C29H36O15 | [M−H]− | 1.43 | Phenylpropanoids | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 106 | Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | 13.76 | 285(68), 284(52), 255(43), 227(26), 151(4) | 593.1523 | C27H30O15 | [M−H]− | 3.79 | Flavonoid | [19,22] |

| 107 | Astilbin or isomer | 13.79 | 303(17), 285(51), 179(15), 151(100), 125(66), 107(19) | 449.1099 | C21H22O11 | [M−H]− | 3.57 | Flavonoid | [16] |

| 108 | Isorhamnetin–dexoyhexoside–hexoside | 14.18 | 623(100), 461(6), 161(65), 135(10), 133(23), 113(10) | 623.1633 | C28H32O16 | [M−H]− | 2.13 | Flavonoid | [21] |

| 109 | 4, 5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | 14.24 | 353(83), 191(100), 179(62), 135(69) | 515.1204 | C25H24O12 | [M−H]− | 1.67 | Organic acid | [17,21] |

| 110 | Coumaric acid hexoside or isomer | 14.26 | 163(100), 135(17), 117(10), 97(3) | 325.0908 | C15H16O7 | [M+H]+ | −2.81 | Phenylpropanoids | [20] |

| 111 | Skimmin | 14.50 | 325(100), 307(16), 163(100), 145(11), 135(19), 117(9) | 325.0908 | C15H16O8 | [M+H]+ | −3.1 | Phenylpropanoids | [20] |

| 112 | Isosctoside or isomer | 14.50 | 623(100), 461(8), 179(3), 161(80), 135(17), 133(23), 113(15) | 623.1989 | C29H36O15 | [M−H]− | 1.22 | Organic acid | [16,20] |

| 113 | Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | 14.51 | 285(48), 284(69), 151(8) | 447.0943 | C21H20O11 | [M−H]− | 2.31 | Flavonoid | [20,22] |

| 114 | Solanigrine D or isomer | 14.57 | 754(100), 736(4), 430(9), 85(13) | 754.4355 | C39H63NO13 | [M+H]+ | −2.3 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 115 | Trifolin | 14.65 | 447(100), 301(80), 300(91), 285(21), 271(49), 255(49), 243(11), 179(14), 151(48), 107(10) | 447.0946 | C21H20O11 | [M−H]− | 2.93 | Flavonoid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 116 | Taxifolin or isomer | 14.68 | 305(7), 287(11), 259(38), 231(32), 213(9), 153(100), 149(37), 123(33) | 305.0647 | C15H12O7 | [M+H]+ | −2.01 | Flavonoid | [16] |

| 117 | Astilbin or isomer | 14.68 | 449(14), 303(17), 285(52), 255(11), 179(17), 151(100), 107(19) | 449.1093 | C21H22O11 | [M−H]− | 0.86 | Flavonoid | [16] |

| 118 | Quercetin–hexoside or isomer | 15.11 | 301(100), 300(5), 273(2), 179(17), 151(39), 107(10) | 463.0893 | C21H20O12 | [M−H]− | 3.22 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 119 | Homoesperetin–dexoyhexoside–hexoside | 15.16 | 623(75), 461(9), 179(3), 161(100), 135(14), 133(33), 113(14) | 623.1991 | C29H36O15 | [M−H]− | 1.53 | Flavonoid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 120 | Luteolin–hexoside | 15.20 | 285(100), 151(8), 133(8) | 447.0941 | C21H20O11 | [M−H]− | 4.24 | Flavonoid | [16,19,20] |

| 121 | Quercetin–hexoside or isomer | 15.26 | 463(5), 301(100), 300(5), 179(18), 151(48) | 463.0892 | C21H20O12 | [M−H]− | 1.77 | Flavonoid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 122 | Solanigrine D or isomer | 15.26 | 754(100), 574(25), 253(8) | 754.4360 | C39H63NO13 | [M+H]+ | −1.65 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 123 | Apigenin–hexoside | 15.31 | 268(100), 151(10) | 431.0991 | C21H20O10 | [M−H]− | 2.73 | Flavonoid | [19] |

| 124 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | 15.41 | 314(47), 285(23), 271(38), 243(43), 151(3) | 477.1046 | C22H22O12 | [M−H]− | 3.96 | Flavonoid | [20,21,22] |

| 125 | Apigetrin | 15.46 | 433(1), 271(100) | 433.1118 | C21H20O10 | [M+H]+ | −2.56 | Flavonoid | [19,20] |

| 126 | Cynaroside or isomer | 16.12 | 447(88), 285(40), 284(100), 151(45), 135(10) | 447.0945 | C21H20O11 | [M−H]− | 2.81 | Flavonoid | [20,22] |

| 127 | Homoplantaginin | 16.60 | 297(10), 283(54), 255(75) | 461.1098 | C22H22O11 | [M−H]− | 3.33 | Flavonoid | [20] |

| 128 | Calceolarioside B | 17.01 | 477(92), 337(28), 175(100), 161(84), 124(23), 123(31) | 477.1410 | C23H26O11 | [M−H]− | 1.64 | Phenylethanoid glycoside | [19,22] |

| 129 | Physalin G | 17.11 | 507(4), 497(11), 481(20), 463(18), 193(5)135(100) | 525.1774 | C28H30O10 | [M−H]− | 3.51 | Steroids | [20] |

| 130 | Luteolin–hexoside or isomer | 17.21 | 285(100), 151(7), 133(8) | 447.0938 | C21H20O11 | [M−H]− | 3.56 | Flavonoid | [16,20] |

| 131 | Trilobatin | 17.37 | 435(44), 420(100), 391(56), 389(57), 335(48), 272(29), 234(77), 206(47), 190(62), 179(39), 135(77) | 435.1304 | C21H24O10 | [M−H]− | 1.75 | Flavonoid | [16] |

| 132 | Luteolin–hexoside or isomer | 17.43 | 285(100), 284(5), 151(7), 133(8) | 447.0941 | C21H20O11 | [M−H]− | 1.41 | Flavonoid | [16,20] |

| 133 | Isorhamnetin–hexoside or isomer | 17.57 | 315(20), 314(55), 299(58), 285(8), 271(49), 151(5) | 477.1042 | C16H12O7 | [M−H]− | 3.01 | Flavonoid | [20,21,22] |

| 134 | Quercetin–hexoside or isomer | 17.63 | 463(41), 301(100), 300(5), 179(26), 151(52) | 463.0888 | C21H20O12 | [M−H]− | 0.95 | Flavonoid | [16,20,22] |

| 135 | Solanigrine B or isomer | 17.91 | 914(100), 897(6), 896(11), 85(13) | 914.4714 | C45H71NO18 | [M+H]+ | −3.3 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 136 | Naringenin–hexoside | 18.09 | 271(100), 151(94), 119(24), 107(22) | 433.1151 | C21H22O10 | [M−H]− | 3.01 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 137 | Solasonine | 18.43 | 866(11), 848(14), 114(4) | 884.4984 | C45H73NO16 | [M+H]+ | −2.04 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 138 | Favolon B | 18.84 | 575(100), 213(11), 157(6) | 575.3563 | C33H50O8 | [M+H]+ | −2.65 | Other | [21] |

| 139 | Genistin | 19.00 | 268(59), 239(66), 211(68) | 431.0988 | C21H20O10 | [M−H]− | 3.43 | Flavonoid | [20,22] |

| 140 | Apigenin 7-(6”-malonylglucoside) | 19.22 | 519(3), 271(100) | 519.1124 | C24H22O13 | [M+H]+ | −1.84 | Flavonoid | [20] |

| 141 | Eriodictyol | 19.30 | 177(3), 161(2), 151(86), 135(100), 107(17) | 287.0564 | C15H12O6 | [M−H]− | 1.12 | Flavonoid | [16,20,22] |

| 142 | Smilaxchinoside C | 19.50 | 901(40), 597(16), 415(46), 271(33), 253(16), 157(13), 145(29) | 901.4772 | C45H72O18 | [M+H]+ | −2.19 | Phenylpropanoids | [19] |

| 143 | Luteolin | 20.10 | 241(2), 199(3), 175(37), 151(13), 133(37) | 285.0408 | C15H10O6 | [M−H]− | 4.13 | Flavonoid | [16,20,22] |

| 144 | Solanine | 20.21 | 868(100), 850(8), 85(10) | 868.5028 | C45H73NO15 | [M+H]+ | −2.87 | Alkaloid | [21] |

| 145 | Quercetin | 20.21 | 301(100), 273(5), 179(28), 151(89), 121(26), 107(28) | 301.0341 | C15H10O7 | [M−H]− | −3.93 | Flavonoid | [21,22] |

| 146 | Peimine | 20.33 | 432(100), 414(11), 161(14) | 432.3462 | C27H45NO3 | [M+H]+ | −2.32 | Alkaloid | [19] |

| 147 | Smilaside B | 20.47 | 735(9), 675(7), 193(12), 175(100), 160(78), 132(21) | 735.2159 | C34H40O18 | [M−H]− | 2.3 | Phenylpropanoids | [16] |

| 148 | Physalin J | 20.58 | 497(14), 463(16), 341(35), 323(31), 149(25), 135(100), 121(13) | 525.1769 | C28H30O10 | [M−H]− | 2.69 | Steroids | [19] |

| 149 | Schidigerasponin A3 | 20.59 | 901(12), 739(25), 415(24), 271(61), 253(100), 157(21) | 901.4777 | C45H72O18 | [M+H]+ | −1.64 | Phenylpropanoids | [19] |

| 150 | Verruculin | 20.60 | 917(100), 755(9), 101(17) | 917.4761 | C47H66N8O11 | [M−H]− | −1.84 | Alkaloid | [19] |

| 151 | Trigoneoside Xb | 20.70 | 919(100), 757(11) | 919.4923 | C45H76O19 | [M−H]− | 1.56 | Steroids | [16,19] |

| 152 | Colisporifungin | 20.71 | 903(16), 741(80), 597(50), 255(100), 161(48) | 903.4934 | C47H66N8O10 | [M+H]+ | −4.56 | Alkaloid | [19] |

| 153 | Timosaponin A1 | 20.71 | 579(27), 417(48), 273(100), 255(33), 161(55), 147(15) | 579.3885 | C33H54O8 | [M+H]+ | −1.13 | Flavonoid | [19,21] |

| 154 | Quercetin–methyl | 20.93 | 300(100), 271(60), 255(26), 243(13), 227(3) | 315.0517 | C16H12O7 | [M−H]− | 1.56 | Flavonoid | [16,22] |

| 155 | Isorhamnetin or isomer | 21.05 | 315(100), 300(77), 271(6), 255(3), 243(3), 227(3), 151(20) | 317.0649 | C16H12O7 | [M+H]+ | −2.01 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 156 | Khasianine | 21.09 | 722(100), 704(9), 157(3), 85(10) | 722.4457 | C39H63NO11 | [M+H]+ | −2.28 | Alkaloid | [21,22] |

| 157 | Physalin E | 21.20 | 507(37), 497(31), 463(42), 193(18), 149(62), 135(100), 121(36) | 525.1774 | C28H30O10 | [M−H]− | 3.62 | Steroids | [19] |

| 158 | Naringenin | 21.47 | 151(70), 119(75), 107(26) | 271.0615 | C15H12O5 | [M−H]− | 1.1 | Flavonoid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 159 | Silybin B | 21.76 | 481(79), 453(25), 301(40), 179(29), 151(24), 125(100), 107(6) | 481.1150 | C25H22O10 | [M−H]− | 1.75 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 160 | Smilaside A | 21.76 | 777(8), 735(3), 193(11), 175(100), 160(83), 134(14), 132(23) | 777.2268 | C36H42O19 | [M−H]− | 2.64 | Phenylpropanoids | [16] |

| 161 | Apigenin | 21.76 | 151(12), 117(23), 107(7) | 269.0461 | C15H10O5 | [M−H]− | 1.65 | Flavonoid | [16,19] |

| 162 | Hesperetin | 21.85 | 286(10), 196(6), 164(37), 151(47), 134(26), 107(18) | 301.0724 | C16H14O6 | [M−H]− | −0.44 | Flavonoid | [16,20,22] |

| 163 | Smilaside G | 22.12 | 809(27), 633(28), 367(21), 175(71), 160(76), 145(100), 117(29) | 809.2316 | C40H42O18 | [M−H]− | 2.21 | Phenylpropanoids | [16] |

| 164 | Silybin | 22.29 | 481(63), 453(34), 301(7), 179(17), 151(15), 125(100) | 481.1151 | C25H22O10 | [M−H]− | 1.82 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 165 | Physalin A | 22.31 | 507(10), 497(7), 463(6), 193(11), 149(100), 121(70) | 525.1766 | C28H30O10 | [M−H]− | 2.12 | Steroids | [19] |

| 166 | Smilaside C | 22.33 | 839(22), 663(26), 193(10), 175(91), 160(100), 145(73), 132(28), 117(27) | 839.2422 | C41H44O19 | [M−H]− | 2.12 | Phenylpropanoids | [16] |

| 167 | Isorhamnetin or isomer | 22.53 | 315(51), 300(100), 271(53), 255(24), 243(13), 227(3), 151(2) | 317.0651 | C16H12O7 | [M+H]+ | −1.62 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 168 | Physalin N or isomer | 22.62 | 507(17), 479(14), 463(8), 193(6), 149(100), 121(68) | 525.1766 | C28H30O10 | [M−H]− | 2.12 | Steroids | [19] |

| 169 | Diosmetin | 22.68 | 284(100), 255(83), 227(59), 151(3) | 299.0566 | C16H12O6 | [M−H]− | 0.17 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 170 | Chrysomycin A | 22.83 | 507(20), 445(13), 419(30), 401(12), 375(19), 357(16), 331(13), 173(100), 157(55) | 507.1665 | C28H28O9 | [M−H]− | 0.56 | Other | [19] |

| 171 | Curtisian Q | 22.83 | 525(52), 507(42), 497(44), 481(16), 479(27), 193(12), 173(11), 149(100) | 561.1539 | C34H26O8 | [M−H]− | −2.88 | Phenylethanoid glycoside | [19] |

| 172 | Homodimericin A | 22.83 | 491(100), 419(7), 333(16), 197(11), 169(13), 155(74) | 491.1695 | C28H26O8 | [M+H]+ | −1.18 | Other | [19] |

| 173 | Smilaside E | 23.09 | 881(29), 821(7), 705(26), 175(100), 161(10), 160(92), 145(74), 132(29), 117(26) | 881.2532 | C43H46O20 | [M−H]− | 2.57 | Phenylpropanoids | [16] |

| 174 | Corchorifatty acid F | 23.22 | 327(33), 309(15), 201(24), 171(100), 137(27), 125(6) | 327.2165 | C18H32O5 | [M−H]− | −3.58 | Other | [19,21] |

| 175 | Aspermeroterpene B | 23.36 | 527(19), 447(23), 403(23), 323(38), 173(15), 149(100) | 527.1931 | C28H32O10 | [M−H]− | 1.48 | Other | [19] |

| 176 | Physalin N or isomer | 23.52 | 507(8), 479(10), 463(9), 193(11), 149(100), 121(98) | 525.1772 | C28H30O10 | [M−H]− | 3.28 | Steroids | [19] |

| 177 | Alldimycin C | 23.71 | 526(6), 509(100), 491(7), 171(11) | 544.2169 | C28H33NO10 | [M+H]+ | −1.48 | Alkaloid | [19] |

| 178 | Tetrahydroxy–dimethoxyflavone | 23.88 | 330(67), 315(5), 287(3), 151(20) | 345.0618 | C17H14O8 | [M−H]− | 3.86 | Flavonoid | [19] |

| 179 | Phylloflavanine | 24.28 | 177(80), 147(100), 145(40), 117(17) | 661.1902 | C35H32O13 | [M+H]+ | −2.09 | Flavonoid | [16] |

| 180 | Trihydroxy–octadecenoic acid | 24.51 | 201(10), 171(56), 127(8) | 329.2337 | C18H34O5 | [M−H]− | 0.99 | Other | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 181 | Arjungenin | 24.56 | 503(100), 401(3) | 503.3389 | C30H48O6 | [M−H]− | 2.21 | Other | [17] |

| 182 | Chrysin | 25.12 | 209(3), 143(5), 107(3) | 253.0511 | C15H10O4 | [M−H]− | 1.45 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 183 | Galangin | 25.53 | 213(3), 169(3) | 269.0461 | C15H10O5 | [M−H]− | 1.87 | Flavonoid | [22] |

| 184 | Licanic acid | 26.38 | 275(100), 257(23), 229(19) | 293.2121 | C18H28O3 | [M−H]− | 3.42 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 185 | Isoorientin 2″-O-(E)-p-coumarate | 26.73 | 549(8), 209(58), 425(17), 121(100) | 593.1314 | C30H26O13 | [M−H]− | 2.26 | Flavonoid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| 186 | Kamlolenic acid | 27.47 | 277(44), 259(3) | 295.226 | C18H30O3 | [M+H]+ | 3.42 | Organic acid | [22] |

| 187 | Ganoleucoin K | 29.05 | 391(32), 279(26), 255(94), 197(100), 152(50), 107(9) | 671.3070 | C36H48O12 | [M−H]− | −0.48 | Other | [19] |

| 188 | Eleostearic acid | 29.37 | 123(11), 109(22), 95(65), 81(87), 67(100) | 279.2310 | C18H30O2 | [M+H]+ | −2.77 | Organic acid | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| No. | Transformations | tR/min | Parent Aglycone | Formula | m/z | Adduct Ion | Error/ppm | MS/MS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | / | 4.17 | Geniposidic acid | C16H22O10 | 373.1147 | [M−H]− | 1.87 | 211(34), 193(5), 167(24), 149(53), 123(100) |

| P2 | / | 4.66 | Catechol | C6H6O2 | 109.0297 | [M−H]− | 1.71 | 91(3), 67(12) |

| M1 | Glucuronide Conjugation | 4.97 | Taxifolin | C21H20O13 | 479.0843 | [M−H]− | 4.741 | 303(100), 285(79), 125(87) |

| M2 | Glucuronide Conjugation | 5.94 | Taxifolin | C21H20O13 | 479.0841 | [M−H]− | 4.43 | 303(100), 285(8), 125(92) |

| P3 | / | 5.99 | 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O4 | 153.0197 | [M−H]− | 2.48 | 109(100), 108(84) |

| P4 | / | 6.44 | Neochlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | 353.0882 | [M−H]− | 1.72 | 191(100), 179(4), 173(5), 135(8) |

| M3 | Hydration, Glucuronide Conjugation | 6.54 | Apigenin | C21H20O12 | 463.0893 | [M−H]− | 4.79 | 287(100), 259(44), 243(10), 125(61) |

| P5 | / | 6.70 | Cryptochlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | 353.0885 | [M−H]− | 1.88 | 191(62), 179(68), 173(100), 135(78), 93(8), 85(12) |

| M4 | Oxidation, Glucournid Conjugation | 6.87 | Hesperetin | C22H22O13 | 493.1000 | [M−H]− | 4.75 | 317(100), 289(35) |

| P6 | / | 7.17 | Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 179.0354 | [M−H]− | 2.13 | 135(100) |

| M5 | Hydration, Glucuronide Conjugation | 7.23 | Apigenin | C21H20O12 | 463.0894 | [M−H]− | 4.94 | 287(100), 259(39), 243(11), 125(59) |

| M6 | Oxidation, Glucournid Conjugation | 7.51 | Hesperetin | C22H22O13 | 493.1000 | [M−H]− | 4.63 | 317(100), 289(33) |

| M7 | Oxidation, Glucournid Conjugation | 8.27 | Hesperetin | C22H22O13 | 493.0998 | [M−H]− | 4.37 | 317(100), 289(41) |

| M8 | Sulfation | 9.04 | Taxifolin | C11H12O5 | 383.0081 | [M−H]− | −3.09 | 383(14), 339(100), 231(25) |

| M9 | Sulfation | 11.02 | Isorhamnetin | C16H12O10S | 395.0085 | [M−H]− | 4.4 | 315(100), 300(28), 151(28) |

| P8 | / | 12.04 | Quercetin–hexoside | C21H20O12 | 463.0897 | [M−H]− | 3.28 | 301(59), 300(83), 271(49), 151(13) |

| P9 | / | 12.40 | Astilbin or isomer | C21H22O11 | 449.1103 | [M−H]− | 2.98 | 303(18), 285(48), 179(15), 151(100), 125(20), 107(17) |

| P9 | / | 12.42 | Baicalein 6-glucuronide | C21H18O11 | 445.0787 | [M−H]− | 2.40 | 269(100), 175(3), 113(15), 97(29) |

| P10 | / | 13.09 | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | 137.0247 | [M−H]− | 2.19 | 93(100) |

| P11 | / | 14.65 | Homoesperetin 7-rutinoside | C29H36O15 | 623.1998 | [M−H]− | 2.60 | 580(10), 402(9), 161(100), 133(28) |

| P12 | / | 14.81 | Astilbin or isomer | C21H22O11 | 449.1101 | [M−H]− | 2.70 | 303(21), 285(64), 179(21), 151(100), 125(27), 107(22) |

| M10 | Glucournide Conjugation | 16.39 | isorhamnetin | C22H20O13 | 491.0844 | [M−H]− | 4.75 | 315(100), 300(73), 271(16), 151(8) |

| P13 | / | 16.60 | Dihydrokaempferide 3-glucuronide | C22H22O12 | 477.1050 | [M−H]− | 2.30 | 301(100), 175(22), 151(44), 134(15), 113(47) |

| M11 | Glucournide Conjugation | 17.31 | isorhamnetin | C22H20O13 | 491.0844 | [M−H]− | 4.75 | 315(94), 300(100), 271(4), 151(16) |

| M12 | Glucournide Conjugation | 18.85 | isorhamnetin | C22H20O13 | 491.0840 | [M−H]− | 4.06 | 315(100), 300(92), 271(21), 151(20) |

| M13 | Sulfation | 19.55 | Luteolin | C15H10O9S | 364.9979 | [M−H]− | 1.61 | 285(100), 257(7), 229(2), 151(17), 133(5) |

| P14 | / | 19.61 | Engeletin | C21H22O10 | 433.1151 | [M−H]− | 2.51 | 257(100), 242(4), 175(30), 113(71), 85(33) |

| M14 | Sulfation | 19.62 | Quercetin | C15H10O10S | 380.9931 | [M−H]− | 2.39 | 301(100), 179(20), 151(53), 107(14) |

| M15 | Sulfation | 19.78 | Isorhamnetin | C16H12O10S | 395.0087 | [M−H]− | 4.95 | 315(100), 300(25), 151(34) |

| M16 | Glucournide Conjugation | 20.09 | isorhamnetin | C22H20O13 | 491.0844 | [M−H]− | 4.81 | 315(100), 300(12), 271(22) |

| M17 | Sulfation | 20.09 | Isorhamnetin | C16H12O10S | 395.0085 | [M−H]− | 4.55 | 315(100), 300(61), 151(17) |

| P15 | / | 20.35 | Luteolin | C15H10O6 | 285.0411 | [M−H]− | 2.36 | 241(2), 199(4), 175(4), 151(8), 133(27) |

| P16 | / | 20.60 | Baicalein 6-glucuronide | C21H18O11 | 445.0787 | [M−H]− | 2.40 | 269(100), 175(3), 113(15), 97(29) |

| P17 | / | 27.91 | 12,27-dihydroxy-solasodine | C27H43NO4 | 446.3251 | [M+H]+ | −3.03 | 271(3), 133(3), 119(9), 85(60) |

| P18 | / | 32.16 | Ursolic acid | C30H48O3 | 455.3545 | [M−H]− | 3.09 | 407(2), 255(3), 219(1), 145(2) |

| Group | IL-6 (pg/mL) | IL-17 (pg/mL) | TNF-α (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 33.40 ± 6.42 | 18.85 ± 5.77 | 98.72 ± 11.8 |

| Model | 102.0 ± 11.6 *** | 82.23 ± 12.1 *** | 248.5 ± 44.2 *** |

| MZBZ | 77.71 ± 9.31 ΔΔ | 64.13 ± 9.89 Δ | 184.6 ± 18.7 ΔΔ |

| Group | p-p65/p65 | p-akt/akt | TGF-β1/Actin | COX2/Actin | Bcl2/Atin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 1.02 ± 0.14 | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 0.93 ± 0.06 |

| Model | 1.17 ± 0.08 *** | 1.33 ± 0.16 *** | 6.28 ± 0.55 *** | 5.28 ± 0.55 *** | 0.25 ± 0.55 *** |

| MZBZ | 0.47 ± 0.07 ΔΔΔ | 0.72 ± 0.06 ΔΔΔ | 2.10 ± 0.52 ΔΔΔ | 2.50 ± 0.29 ΔΔ | 0.63 ± 0.07 ΔΔ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maihemuti, M.; Nuermaimaiti, M.; Maimaitiming, W.; Paierhati, A.; Ji, H.; Abduwaki, M.; Yang, X.; Mohammadtursun, N. UHPLC–Q–Orbitrap–HRMS-Based Multilayer Mapping of the Pharmacodynamic Substance Basis and Mechanistic Landscape of Maizibizi Wan in Chronic Nonbacterial Prostatitis Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010153

Maihemuti M, Nuermaimaiti M, Maimaitiming W, Paierhati A, Ji H, Abduwaki M, Yang X, Mohammadtursun N. UHPLC–Q–Orbitrap–HRMS-Based Multilayer Mapping of the Pharmacodynamic Substance Basis and Mechanistic Landscape of Maizibizi Wan in Chronic Nonbacterial Prostatitis Therapy. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010153

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaihemuti, Maimaitiming, Muaitaer Nuermaimaiti, Wuermaitihan Maimaitiming, Alimujiang Paierhati, Hailong Ji, Muhammatjan Abduwaki, Xinzhou Yang, and Nabijan Mohammadtursun. 2026. "UHPLC–Q–Orbitrap–HRMS-Based Multilayer Mapping of the Pharmacodynamic Substance Basis and Mechanistic Landscape of Maizibizi Wan in Chronic Nonbacterial Prostatitis Therapy" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010153

APA StyleMaihemuti, M., Nuermaimaiti, M., Maimaitiming, W., Paierhati, A., Ji, H., Abduwaki, M., Yang, X., & Mohammadtursun, N. (2026). UHPLC–Q–Orbitrap–HRMS-Based Multilayer Mapping of the Pharmacodynamic Substance Basis and Mechanistic Landscape of Maizibizi Wan in Chronic Nonbacterial Prostatitis Therapy. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010153