Molecular Interaction and Biological Activity of Fatty Acids and Sterols: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach Against Haemonchus contortus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. ADMET Analysis

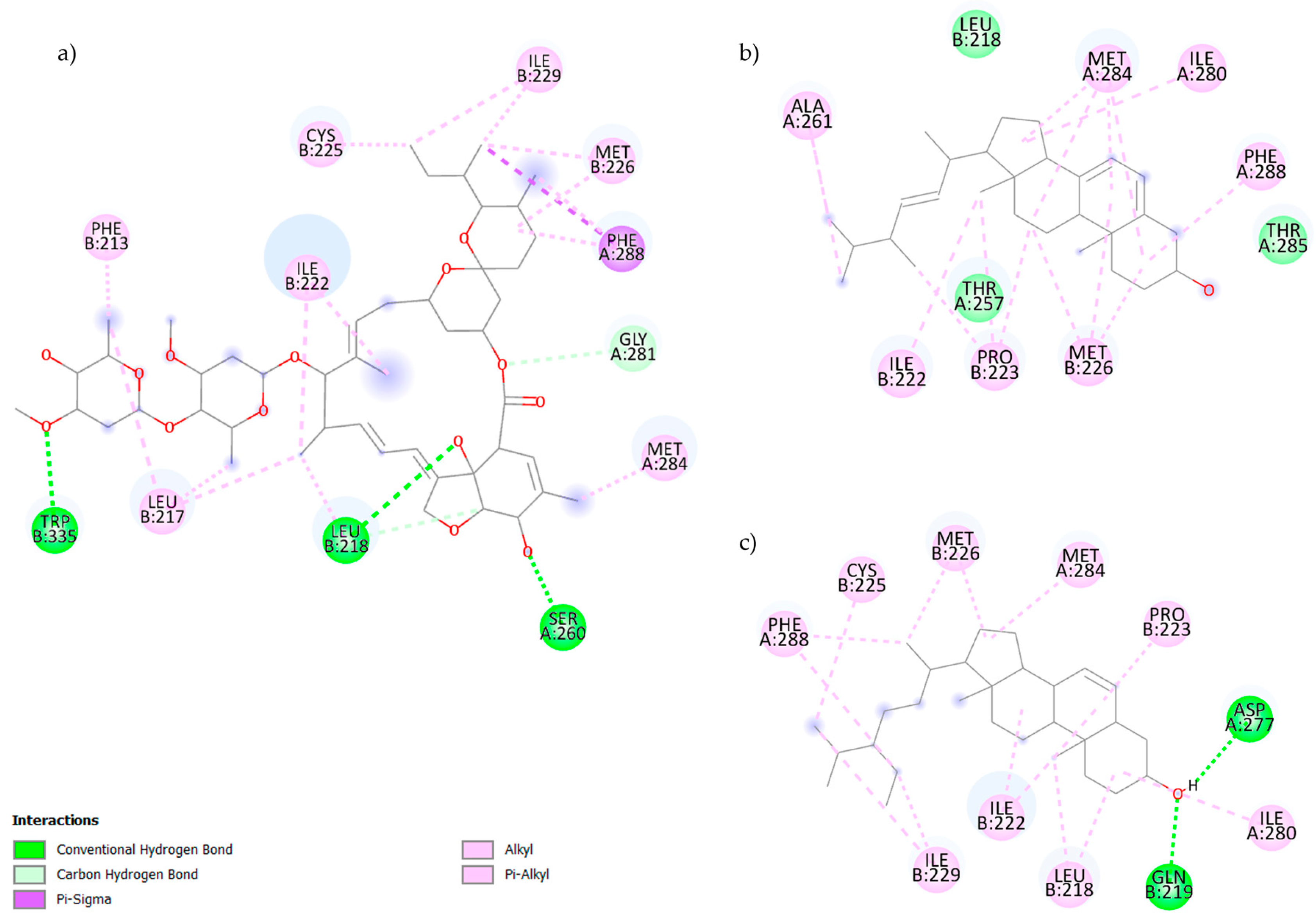

2.2. Molecular Docking

2.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

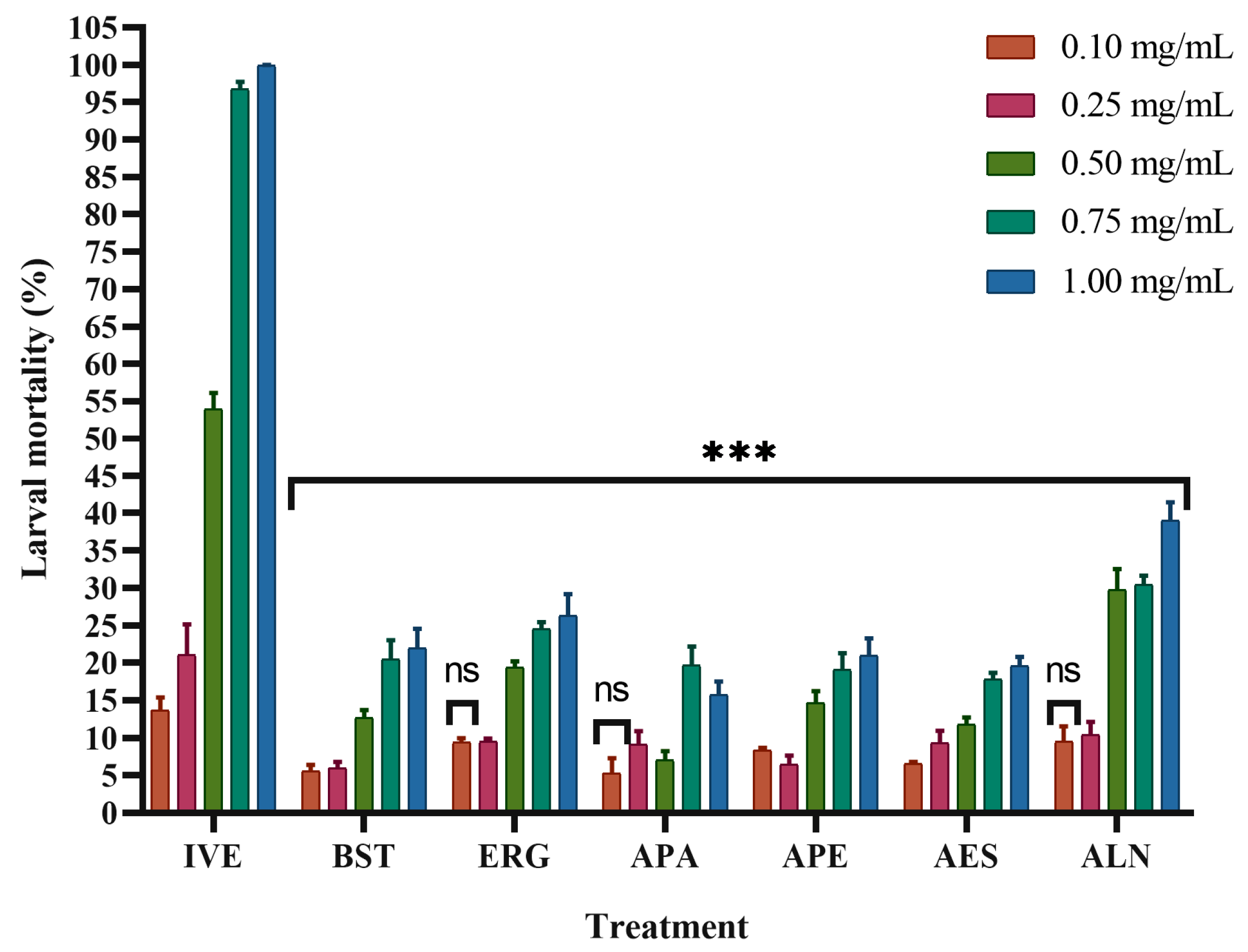

2.4. In Vitro Mortality Test

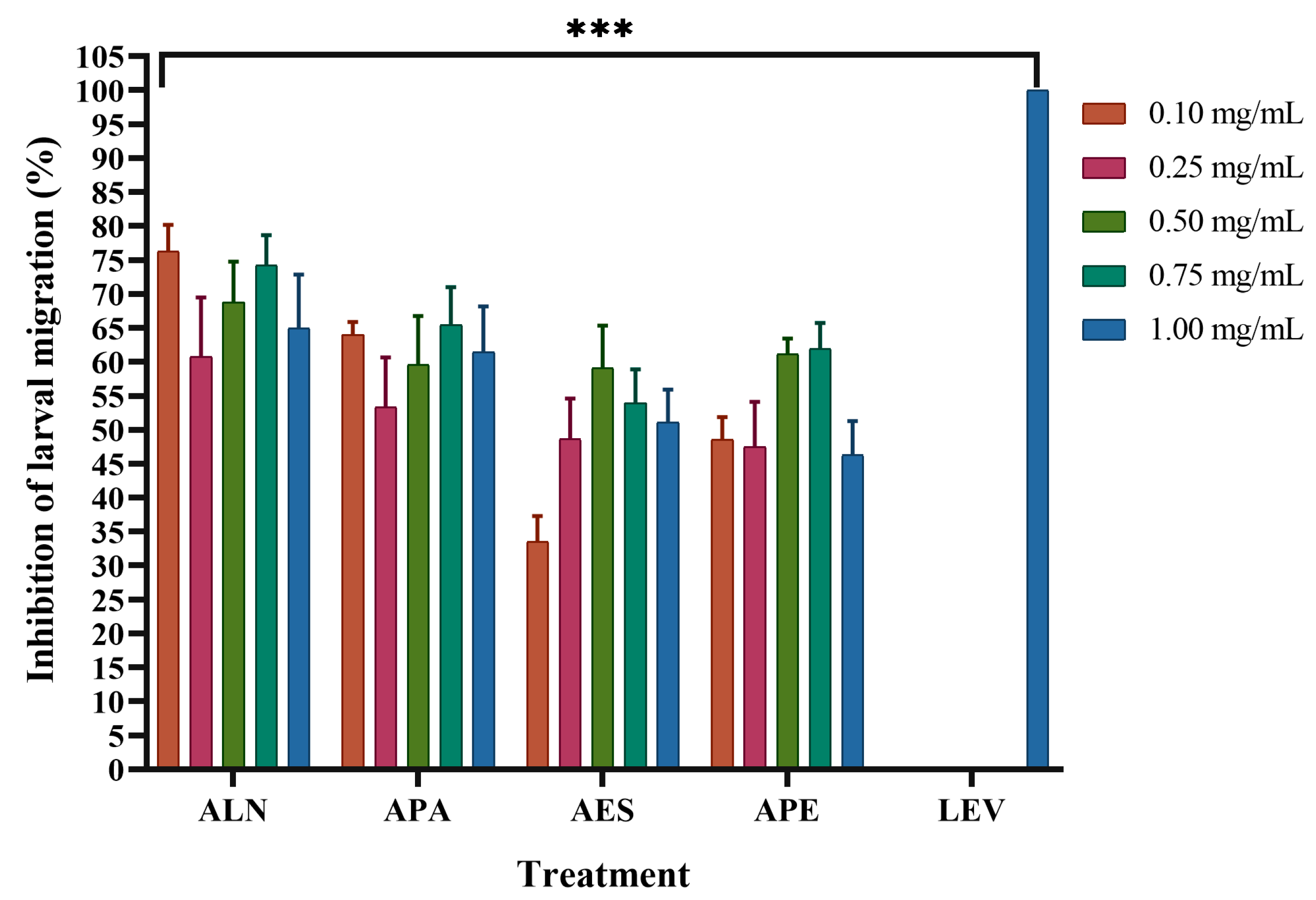

2.5. Larval Migration Test

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. ADMET Analysis

4.2. In Silico Analysis

4.2.1. Obtaining Molecular Structures

4.2.2. Structural Optimization with Avogadro

4.2.3. Preparation of H. contortus Proteins

4.2.4. Molecular Docking

4.2.5. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

4.3. In Vitro Assays

4.3.1. Commercial Compounds

4.3.2. Haemonchus contortus Donor Animal

4.3.3. Obtaining Infective Larvae Without Sheaths

4.3.4. Larval Mortality Test

4.3.5. Larval Migration Test

4.3.6. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Besier, R.B.; Kahn, L.P.; Sargison, N.D.; van Wyk, J.A. The Pathophysiology, Ecology and Epidemiology of Haemonchus contortus Infection in Small Ruminants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 93, ISBN 9780128103951. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Katsarou, E.I.; Papadopoulos, E. Haemonchosis: A challenging parasitic infection of sheep and goats. Animals 2021, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fissiha, W.; Kinde, M.Z. Anthelmintic resistance and its mechanism: A review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 5403–5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politi, F.A.S.; Bueno, R.V.; Zeoly, L.A.; Fantatto, R.R.; de Oliveira Eloy, J.; Chorilli, M.; Furlan, M. Anthelmintic activity of a nanoformulation based on thiophenes identified in Tagetes patula L. (Asteraceae) against the small ruminant nematode Haemonchus contortus. Acta Trop. 2021, 219, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vineer, H.R.; Morgan, E.R.; Hertzberg, H.; Bartley, D.J.; Bosco, A.; Charlier, J.; Rinaldi, L. Increasing importance of anthelmintic resistance in European livestock: Creation and meta-analysis of an open database. Parasite 2020, 27, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotze, A.C.; Prichard, R.K. Anthelmintic resistance in Haemonchus contortus. In Advances in Parasitology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 93, pp. 397–428. [Google Scholar]

- Charlier, J.; Bartley, D.J.; Sotiraki, S.; Martínez-Valladares, M.; Claerebout, E.; Samson-Himmelstjerna, G.; Thamsborg, S.M.; Hoste, H.; Morgan, E.R.; Rinaldi, L. Anthelmintic resistance in rumiants: Challenges and solutions. In Advances in Parasitology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 115, pp. 171–227. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Ruan, W.; Deng, Y.; Gao, Y. Potential antagonistic effects of nine natural fatty acids against Meloidogyne incognita. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 11631–11637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Alegría, J.A.; Sánchez-Vázquez, J.E.; González-Cortazar, M.; Zamilpa, A.; López-Arellano, M.E.; Cuevas-Padilla, E.J.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L. The edible mushroom Pleurotus djamor produces metabolites with lethal activity against the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.K.; Das, R.; Mai, A.H.; De Borggraeve, W.M.; Luyten, W. Nematicidal activity of Holigarna caustica fruit is due to linoleic acid. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; D’Apolito, O.; Garofalo, D.; Paglia, G.; Russo, A.D. Profiling of acylcarnitines and sterols from dried blood or plasma spot by APTDCI tandem mass spectrometry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2011, 1811, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meco López, J.F.; Pascual, F.V.; Alberichc, R.S. La utilización de los esteroles vegetales en la práctica clínica: De la química a la clínica. Clín. Investig. Arterioscler. 2016, 28, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak, M.; Dipankar, G.; Prashanth, D.; Asha, M.K.; Amit, A.; Venkataraman, B.V. Tribulosin and β-sitosterol-D-glucoside, the anthelmintic principles of Tribulus terrestris. Phytomedicine 2002, 9, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanelli, F.; Mattellini, M.; Fichi, G.; Flamini, G.; Perrucci, S. In vitro anthelmintic activity of four plant-derived compounds against sheep gastrointestinal nematodes. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Alegría, J.A.; Sánchez, J.E.; González-Cortazar, M.; Von Son-de Fernex, E.; González-Garduño, R.; Mendoza-de Gives, P.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L. In Vitro nematicidal activity of commercial fatty acids and β-sitosterol against Haemonchus contortus. J. Helminthol. 2020, 94, e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, V.; Jagannathan, S.; Wolstenholme, A.J. Distribution of glutamate-gated chloride channel subunits in the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003, 462, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbs, R.E.; Gouaux, E. Principles of activation and permeation in an anion-selective Cys-loop receptor. Nature 2011, 474, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouic, P.J. The role of phytosterols and phytosterolins in immune modulation: A review of the past 10 years. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2001, 4, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Azorsa, R.; Cruz-Santiago, H.; Cid del Prado-Vera, I.; Ramirez-Mares, M.V.; Gutiérrez-Ortiz, M.d.R.; Santos-Sánchez, N.F.; Salas-Coronado, R.; Villanueva-Cañongo, C.; Lira-de León, K.I.; Hernández-Carlos, B. Chemical Characterization of Plant Extracts and Evaluation of their Nematicidal and Phytotoxic Potential. Molecules 2021, 26, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, H.L.; Gaylord, E.A.; Doering, T.L. Ergosterol distribution controls surface structure formation and fungal pathogenicity. mBio 2023, 14, e01353-e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, S.; Moudgil, M.; Mandal, S.K. Rational drug design. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 625, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desany, B.; Zhang, Z. Bioinformatics and cancer target discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2004, 9, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynagh, T.; Lynch, J.W. Molecular mechanisms of Cys-loop ion channel receptor modulation by ivermectin. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2012, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, M.; Mayer, A.; Anke, H.; Sterner, O. Fatty acids and other compounds with nematicidal activity from cultures of Basidiomycetes. Planta Med. 1994, 60, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.L.; Meyers, D.M.; Dullum, C.J.; Feitelson, J.S. Nematicidal activity of fatty acid esters on soybean cyst and root-knot nematodes. J. Nematol. 1997, 29, 677–684. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Kipanga, P.; Mai, A.H.; Dhondt, I.; Braeckman, B.P.; De Borggraeve, W.; Luyten, W. Bioassay-guided isolation of three anthelmintic compounds from Warburgia ugandensis and the mechanism of action of polygodial. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018, 48, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.R.; Brooks, C.L., III; Mackerell, A.D., Jr.; Nilsson, L.; Petrella, R.J.; Roux, B.; Won, Y.; Archontis, G.; Bartels, C.; Boresch, S. CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 1545–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cheng, X.; Jo, S.; MacKerell, A.D.; Klauda, J.B.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI input generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM simulations. Biophys. J. 2016, 110, 641a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High-performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism. SoftwareX 2015, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páll, S.; Abraham, M.J.; Kutzner, C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. Tackling exascale software challenges with GROMACS. In Solving Software Challenges for Exascale; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pronk, S.; Páll, S.; Schulz, R.; Larsson, P.; Bjelkmar, P.; Apostolov, R.; Shirts, M.R.; Smith, J.C.; Kasson, P.M.; van der Spoel, D. GROMACS 4.5: A high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.; Kutzner, C.; Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-Pérez, J.I.; Torres-Acosta, J.F.J.; Sandoval-Castro, C.A.; Castañeda-Ramírez, G.S.; Vilarem, G.; Mathieu, C.; Hoste, H. Susceptibility of Haemonchus contortus isolates to acetone: Water extracts of polyphenol-rich plants. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 240, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Acosta, J.F.J.; Chan-Pérez, I.; López-Arellano, M.E.; Rosado-Aguilar, J.A.; Soberanes-Céspedes, N.; Neri-Orantes, S.; Alonso-Díaz, M.A.; Martínez-Ibáñez, F.; Osorio-Miranda, J. Diagnóstico de resistencia a los antiparasitarios en rumiantes. In Técnicas Para el Diagnóstico de Parásitos con Importancia en Salud Pública y Veterinaria; Rodríguez-Vivas, R.I., Ed.; AMPAVE–CONASA: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2015; pp. 355–403. [Google Scholar]

- Páez-León, S.Y.; Carrillo-Morales, M.; Gómez-Rodríguez, O.; López-Guillén, G.; Castañeda-Ramírez, G.S.; Hernández-Núñez, E.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L. Nematicidal activity of leaf extract of Moringa oleifera against Haemonchus contortus and Nacobbus aberrans. J. Helminthol. 2022, 96, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeler, J.; Küttler, U.; El-Abdellati, A.; Stafford, K.; Rydzik, A.; Varady, M.; Kenyon, F.; Coles, G.; Höglund, J.; Jackson, F.; et al. Standardization of the larval migration inhibition test for detecting resistance to ivermectin in ruminant nematodes. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 174, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Rotatable Links | H Acceptors | H Donors | Bioavailability | Synthetic Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APA | 256.42 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 0.85 | 2.31 |

| APE | 242.40 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 0.85 | 2.20 |

| AES | 284.48 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 0.85 | 2.54 |

| ALN | 280.45 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 0.85 | 2.54 |

| BST | 414.71 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.55 | 6.30 |

| ERG | 396.65 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.55 | 6.58 |

| Compound | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| Ivermectin (IVE) | −13.57 |

| Ergosterol (ERG) | −10.25 |

| β-sitosterol (BST) | −10.18 |

| Linoleic acid (ALN) | −4.59 |

| Palmitic acid (APA) | −4.47 |

| Pentadecanoic acid (APE) | −4.36 |

| Stearic acid (AES) | −4.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Páez-León, S.Y.; Cardoso-Taketa, A.; Madariaga-Mazón, A.; Morales-Martínez, A.; Torres-Acosta, J.F.d.J.; Mancilla-Montelongo, G.; Hernández-Velázquez, V.M.; Navarrete-Vázquez, G.; Villegas, E.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L. Molecular Interaction and Biological Activity of Fatty Acids and Sterols: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach Against Haemonchus contortus. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010140

Páez-León SY, Cardoso-Taketa A, Madariaga-Mazón A, Morales-Martínez A, Torres-Acosta JFdJ, Mancilla-Montelongo G, Hernández-Velázquez VM, Navarrete-Vázquez G, Villegas E, Aguilar-Marcelino L. Molecular Interaction and Biological Activity of Fatty Acids and Sterols: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach Against Haemonchus contortus. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010140

Chicago/Turabian StylePáez-León, Susan Yaracet, Alexandre Cardoso-Taketa, Abraham Madariaga-Mazón, Adriana Morales-Martínez, Juan Felipe de Jesús Torres-Acosta, Gabriela Mancilla-Montelongo, Víctor Manuel Hernández-Velázquez, Gabriel Navarrete-Vázquez, Elba Villegas, and Liliana Aguilar-Marcelino. 2026. "Molecular Interaction and Biological Activity of Fatty Acids and Sterols: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach Against Haemonchus contortus" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010140

APA StylePáez-León, S. Y., Cardoso-Taketa, A., Madariaga-Mazón, A., Morales-Martínez, A., Torres-Acosta, J. F. d. J., Mancilla-Montelongo, G., Hernández-Velázquez, V. M., Navarrete-Vázquez, G., Villegas, E., & Aguilar-Marcelino, L. (2026). Molecular Interaction and Biological Activity of Fatty Acids and Sterols: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach Against Haemonchus contortus. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010140