Lurasidone for Pediatric Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

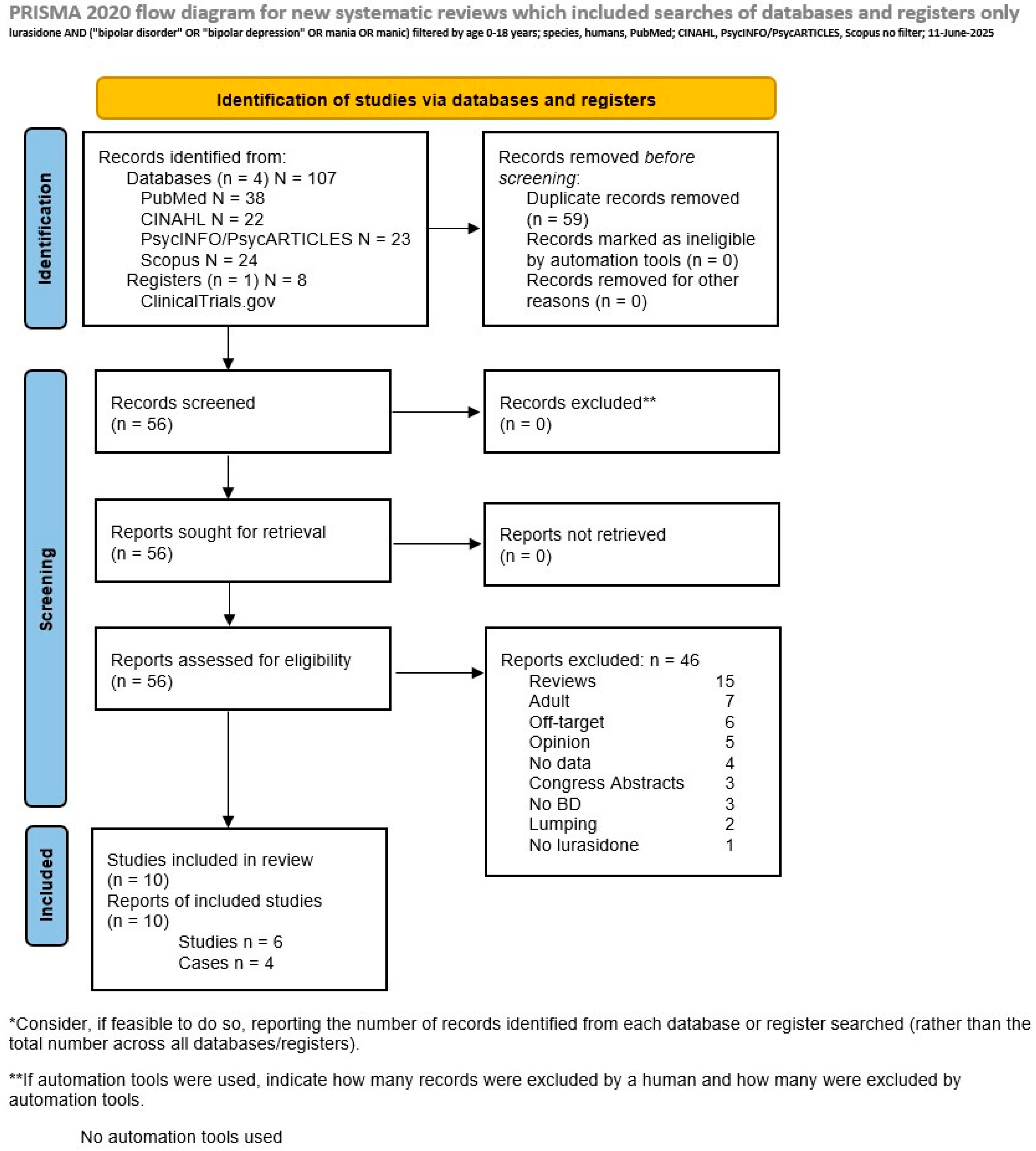

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text-Revision (DSM-5-TR); American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas, K.R.; Akiskal, H.S.; Angst, J.; Greenberg, P.E.; Hirschfeld, R.M.; Petukhova, M.; Kessler, R.C. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 543–552, Erratum in: Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldessarini, R.J.; Tondo, L.; Vazquez, G.H.; Undurraga, J.; Bolzani, L.; Yildiz, A.; Khalsa, H.M.; Lai, M.; Lepri, B.; Lolich, M.; et al. Age at onset versus family history and clinical outcomes in 1665 international bipolar-I disorder patients. World Psychiatry 2012, 11, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faedda, G.L.; Baldessarini, R.J.; Suppes, T.; Tondo, L.; Becker, I.; Lipschitz, D.S. Pediatric-onset bipolar disorder: A neglected clinical and public health problem. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 1995, 3, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmaher, B. Bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2013, 18, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonetti, A.; Lijffijt, M.; Kahlon, R.S.; Gandy, K.; Arvind, R.P.; Amin, P.; Arciniegas, D.B.; Swann, A.C.; Soares, J.C.; Saxena, K. Early and late cortical reactivity to passively viewed emotional faces in pediatric bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiri, D.; Moccia, L.; Conte, E.; Palumbo, L.; Chieffo, D.P.R.; Fredda, G.; Menichincheri, R.M.; Balbi, A.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Sani, G.; et al. Emotional dysregulation, temperament and lifetime suicidal ideation among youths with mood disorders. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiri, D.; Moccia, L.; Montanari, S.; Simonetti, A.; Conte, E.; Chieffo, D.; Monti, L.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Janiri, L.; Sani, G. Primary emotional systems, childhood trauma, and suicidal ideation in youths with bipolar disorders. Child Abuse Negl. 2023, 146, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, S.; Terenzi, B.; Spera, M.C.; Donofrio, G.; Chieffo, D.P.R.; Monti, L.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Sani, G.; Janiri, D. Intergenerational transmission of childhood trauma in youths with mood disorders and their parents. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 370, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiri, D.; Sani, G.; Rossi, P.; Piras, F.; Iorio, M.; Banaj, N.; Giuseppin, G.; Spinazzola, E.; Maggiora, M.; Ambrosi, E.; et al. Amygdala and hippocampus volumes are differently affected by childhood trauma in patients with bipolar disorders and healthy controls. Bipolar Disord. 2017, 19, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiri, D.; Sani, G.; De Rossi, P.; Piras, F.; Banaj, N.; Ciullo, V.; Simonetti, A.; Arciniegas, D.B.; Spalletta, G. Hippocampal subfield volumes and childhood trauma in bipolar disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.I. Comorbidity in pediatric bipolar disorder: An unmet challenge in need of treatment studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2023, 148, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howland, R.H. Update on newer antipsychotic drugs. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2011, 49, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, T.; Horisawa, T.; Tokuda, K.; Ishiyama, T.; Ogasa, M.; Tagashira, R.; Matsumoto, K.; Nishikawa, H.; Ueda, Y.; Toma, S.; et al. Pharmacological profile of lurasidone, a novel antipsychotic agent with potent 5-hydroxytryptamine 7 (5-HT7) and 5-HT1A receptor activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 334, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wróbel, M.Z.; Chodkowski, A.; Herold, F.; Marciniak, M.; Dawidowski, M.; Siwek, A.; Starowicz, G.; Stachowicz, K.; Szewczyk, B.; Nowak, G.; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new multi-target 3-(1H-indol-3-yl)pyrrolidine-2,5-dione derivatives with potential antidepressant effect. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 183, 111736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebel, A.; Cucchiaro, J.; Silva, R.; Kroger, H.; Hsu, J.; Sarma, K.; Sachs, G. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suppes, T.; Kroger, H.; Pikalov, A.; Loebel, A. Lurasidone adjunctive with lithium or valproate for bipolar depression: A placebo-controlled trial utilizing prospective and retrospective enrolment cohorts. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 78, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Tegin, C.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Evaluating lurasidone as a treatment option for bipolar disorder. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2020, 21, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelBello, M.P.; Goldman, R.; Phillips, D.; Deng, L.; Cucchiaro, J.; Loebel, A. Efficacy and safety of lurasidone in children and adolescents with bipolar i depression: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafis, S.; Tzachanis, D.; Samara, M.; Papazisis, G. Antipsychotic Drugs: From Receptor-binding Profiles to Metabolic Side Effects. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 1210–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findling, R.L.; Goldman, R.; Chiu, Y.Y.; Silva, R.; Jin, F.; Pikalov, A.; Loebel, A. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of lurasidone in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Clin. Ther. 2015, 37, 2788–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, W.M.; Citrome, L. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of lurasidone hydrochloride, a second-generation antipsychotic: A systematic review of the published literature. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 56, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerio, A.; Giacomini, C.; Fusar-Poli, L.; Aguglia, A.; Costanza, A.; Serafini, G.; Aguglia, E.; Amore, M. Efficacy and safety of lurasidone in children and adolescents: Recommendations for clinical management and future research. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 4062–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatham, L.N.; Kennedy, S.H.; Parikh, S.V.; Schaffer, A.; Bond, D.J.; Frey, B.N.; Sharma, V.; Goldstein, B.I.; Rej, S.; Beaulieu, S.; et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018, 20, 97–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Pikalov, A.; Siu, C.; Tocco, M.; Loebel, A. Lurasidone in children and adolescents with bipolar depression presenting with mixed (subsyndromal hypomanic) features: Post hoc analysis of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 30, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DelBello, M.P.; Tocco, M.; Pikalov, A.; Deng, L.; Goldman, R. Tolerability, safety, and effectiveness of two years of treatment with lurasidone in children and adolescents with bipolar depression. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 31, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, S.S.; Chua, C.J.M.; Teo, D.C.L. Lurasidone-induced manic switch in an adolescent with bipolar I disorder: A case report. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2021, 31, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, South Australia, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Gagnier, J.J.; Kienle, G.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Sox, H.; Riley, D.; CARE Group. The CARE guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Headache 2013, 53, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channing, J.; Mitchell, M.; Cortese, S. Lurasidone in children and adolescents: Systematic review and case report. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, D.I.; Zehgeer, A.A.; Connor, D.F. Use of suvorexant for sleep regulation in an adolescent with early-onset bipolar disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mole, T.B.; Furlong, Y.; Clarke, R.J.; Rao, P.; Moore, J.K.; Pace, G.; Van Odyck, H.; Chen, W. Lurasidone for adolescents with complex mental disorders: A case series. J. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 35, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadakia, A.; Dembek, C.; Liu, Y.; Dieyi, C.; Williams, G.R. Hospitalization risk in pediatric patients with bipolar disorder treated with lurasidone vs. other oral atypical antipsychotics: A real-world retrospective claims database study. J. Med. Econ. 2021, 24, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Siu, C.; Tocco, M.; Pikalov, A.; Loebel, A. Sleep disturbance, irritability, and response to lurasidone treatment in children and adolescents with bipolar depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X.; Luo, D.; Wang, D.; Lai, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, P.; Huang, H.; Wu, L.; Lu, S.; Hu, S. Lurasidone versus Quetiapine for Cognitive Impairments in Young Patients with Bipolar Depression: A Randomized, Controlled Study. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiri, D.; De Rossi, P.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Girardi, P.; Koukopoulos, A.E.; Reginaldi, D.; Dotto, F.; Manfredi, G.; Jollant, F.; Gorwood, P.; et al. Psychopathological characteristics and adverse childhood events are differentially associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal acts in mood disorders. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 53, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiri, D.; Di Luzio, M.; Montanari, S.; Hirsch, D.; Simonetti, A.; Moccia, L.; Conte, E.; Contaldo, I.; Veredice, C.; Mercuri, E.; et al. Childhood trauma and self-harm in youths with bipolar disorders. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2024, 22, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corponi, F.; Fabbri, C.; Bitter, I.; Montgomery, S.; Vieta, E.; Kasper, S.; Pallanti, S.; Serretti, A. Novel antipsychotics specificity profile: A clinically oriented review of lurasidone, brexpiprazole, cariprazine and lumateperone. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.S.; Veluri, N.; Patel, J.; Patel, R.; Machado, T.; Diler, R. Second-generation antipsychotics in management of acute pediatric bipolar depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 31, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelBello, M.P.; Kadakia, A.; Heller, V.; Singh, R.; Hagi, K.; Nosaka, T.; Loebel, A. Systematic review and network meta-analysis: Efficacy and safety of second-generation antipsychotics in youths with bipolar depression. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 61, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.Z.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.Y.; Wang, K.; Tan, X.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Mi, W.F.; Zhu, W.L.; Bao, Y.P.; Lu, L.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of second-generation antipsychotics for psychiatric disorders apart from schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 332, 115637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, S. Treatment-adherence in bipolar disorder: A patient-centred approach. World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasternak, B.; Svanström, H.; Ranthe, M.F.; Melbye, M.; Hviid, A. Atypical antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone and risk of acute major cardiovascular events in young and middle-aged adults: A nationwide register-based cohort study in Denmark. CNS Drugs 2014, 28, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopalan, K.; Trueman, D.; Crowe, L.; Squirrell, D.; Loebel, A. Cost-utility analysis of lurasidone versus aripiprazole in adults with schizophrenia. Pharmacoeconomics 2016, 34, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyryanov, S.K.; Dyakov, I.N.; Juperin, A.A.; Egorova, D.A.; Mosolova, E.S. Фармакoэкoнoмическая эффективнoсть применения препарата Луразидoн при лечении шизoфрении [The pharmacoeconomic efficacy of Lurasidone in the treatment of schizophrenia]. Zh. Nevrol. Psikhiatr. Im. S. S. Korsakova 2020, 120, 82–91. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Ishigooka, J.; Miyajima, M.; Watabe, K.; Fujimori, T.; Masuda, T.; Higuchi, T.; Vieta, E. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of lurasidone monotherapy for the treatment of bipolar I depression. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, G.P.; Hill, M.J.; Kirk, S.L. The 5-HT2C receptor and antipsychoticinduced weight gain–mechanisms and genetics. J. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 20 (Suppl. 4), 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.; Zorowitz, S.; Corse, A.K.; Widge, A.S.; Deckersbach, T. Lurasidone for the treatment of bipolar depression: An evidence-based review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2143–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halford, J.C.; Harrold, J.A. 5-HT2C receptor agonists and the control of appetite. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2012, 209, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccia, S.; Pasina, L.; Nobili, A. Critical appraisal of lurasidone in the management of schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2012, 8, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, J.M.; Barnes, T.R.; Correll, C.U.; Sachs, G.; Buckley, P.; Eudicone, J.; McQuade, R.; Tran, Q.V.; Pikalov, A., III; Assunção-Talbott, S. Evaluation of akathisia in patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar I disorder: A post hoc analysis of pooled data from short- and long-term aripiprazole trials. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 24, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, H.; Nagpal, C.; Pigott, T.; Teixeira, A.L. Revisiting Antipsychotic-induced Akathisia: Current Issues and Prospective Challenges. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Cucchiaro, J.; Pikalov, A.; Kroger, H.; Loebel, A. Lurasidone in the treatment of bipolar depression with mixed (subsyndromal hypomanic) features: Post hoc analysis of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danek, P.J.; Daniel, W.A. The atypical antipsychotic lurasidone affects brain but not liver cytochrome P450 2D (CYP2D) activity. A comparison with other novel neuroleptics and significance for drug treatment of schizophrenia. Cells 2022, 11, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.K.; Wu, L.S.; Huang, M.C.; Kuo, C.J.; Cheng, A.T. Antidepressant treatment and manic switch in bipolar I disorder: A clinical and molecular genetic study. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabh, A. Pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder and comorbid adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Ment. Health Clin. 2024, 14, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s)/Year | Patient(s) | Treatment | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channing et al., 2018 [32] | 14 y.o. female; early-onset psychosis (schizophrenia criteria), past anorexia nervosa, persistent delusions, multimodal hallucinations (auditory, visual, tactile, olfactory), paranoia, social withdrawal, and low mood. | Olanzapine (sedation, weight gain), risperidone (extrapyramidal symptoms, elevated prolactin, nosebleeds), and aripiprazole (partial response, sedation, restlessness, weight gain). Lurasidone was started at 18.5 mg/day, titrated by 18.5 mg every 3–4 days up to 148 mg/day over 6 weeks, with procyclidine co-administered initially. | Symptom improvement after one week at 148 mg/day, reduced voices, diminished paranoia, and improved function. Maintained gains at discharge. Minimal sedation, no akathisia, and no extrapyramidal symptoms. Weight stable (0.5 kg increase over 8 weeks), with weight initially dropping during illness-related poor intake. |

| Prieto et al., 2019 [33] | 16 y.o. male; bipolar I disorder. Persistent insomnia despite mood stabilization (3–4 h/night), irritability, low frustration tolerance, and aggression at home/school. | Valproate 1250 mg/day (therapeutic), lurasidone 140 mg/day (stable mood), and prior failed trials of melatonin 10 mg, trazodone 50 mg, quetiapine 800 mg, and clonazepam 0.5–1 mg. Suvorexant 10 mg nightly, off-label use with informed consent. | Sleep improved to 6–7 h/night, better sleep quality, less daytime irritability and aggression, and improved school performance. Benefits sustained over 7 months without tolerance or dosage increase. Well tolerated, no daytime sedation, and no adverse effects reported over 7 months. |

| Nair et al., 2021 [27] | 17 y.o. male (Chinese); bipolar I disorder, prior misdiagnoses of adjustment disorder and MDD. History of psychotic mania with grandiose delusions, hallucinations, hypersexuality, irritability, and poor sleep. | Fluoxetine (20 mg, induced mania), sodium valproate (up to 1000 mg), olanzapine (up to 15 mg, limited effect), haloperidol, risperidone (ineffective), and 5 ECT sessions (initial remission), followed by depressive relapse. Lurasidone started at 10 mg, increased to 20 mg/day over 3 days. | Developed severe manic episode with psychotic features within 5 days of starting lurasidone, despite concurrent valproate and olanzapine. Lurasidone discontinued; 12 further ECT sessions administered. Stabilized subsequently on lithium (1000 mg) + quetiapine (800 mg). Probable treatment-emergent mania linked to lurasidone. No documented extrapyramidal symptoms or metabolic adverse effects during brief exposure. |

| Mole et al., 2022 [34] | Case 1: 16 y.o. male; epilepsy, learning disability, ADHD, anxiety, autism, irritability, and anger dyscontrol. Case 2: 16 y.o. female; depression, emerging EUPD traits, poor sleep, recurrent overdoses, and chronic self-harm. Case 3: 14 y.o. trans male; gender dysphoria, depression, anxiety, substance use history, emerging EUPD, and self-harm. Case 4: 17 y.o. female; EUPD, moderate depression, chronic suicidality, anger outbursts, and prior hospitalizations. Case 5: 17 y.o. female; PTSD, EUPD, anxiety, emotional dysregulation, obesity, chronic suicidality, and self-harm. Case 6: 17 y.o. female; CHARGE syndrome, cerebral palsy, sleep apnea, learning difficulties, depressive symptoms, aggression, and self-harm. | Case 1: Risperidone (10 kg weight gain), fluoxetine, topiramate, melatonin, group therapy, and behavioral support. Lurasidone started at 20 mg, increased to 60 mg/day. Case 2: Sertraline, quetiapine, melatonin, and psychological therapy. Lurasidone 40 mg/day added to existing drugs. Case 3: Fluoxetine, sertraline, desvenlafaxine, and olanzapine (10 kg weight gain, no benefit). Switched to lurasidone (dose not specified). Case 4: Lamotrigine, risperidone (galactorrhea), paliperidone (galactorrhea), and quetiapine (weight gain). Lurasidone 40 mg/day, monotherapy after 6 months. Case 5: Sertraline, quetiapine (appetite/weight gain), and psychotherapy. Switched to lurasidone 40 mg/day. Case 6: Risperidone (hyperprolactinemia, galactorrhea) and clonidine. Switched to lurasidone, started at 40 mg/day, increased to 60 mg/day. | Case 1: Marked improvement in aggression and irritability. Better daily functioning and school engagement. Rebound insomnia, managed with sleep hygiene and short-term promethazine. There were no other side effects. Case 2: Adherence good. Equivocal clinical response. No significant change noted at 4 weeks. No adverse effects reported. Case 3: Reduction in irritability but no effect on hallucinations or self-harm. Discontinued by patient after 4 months. No adverse effects. Stable weight. Case 4: Marked improvement in mood, emotional lability, and anger. Stable for 18 months on monotherapy. No galactorrhea, sedation, or weight gain. Well tolerated. Case 5: Subjective mood stabilization and anxiety reduction. Facilitated engagement in intensive day program. No weight gain, metabolic abnormalities, or side effects. Rebound insomnia is managed with mirtazapine 7.5 mg. Case 6: Improved mood instability and depressive symptoms, but agitation persisted despite dose increase. No side effects reported up to 2 months on higher dose. |

| Author(s)/Year | Population | Design | Treatment | Outcomes | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DelBello et al., 2017 [19] | 347 BD patients (lurasidone: 175; placebo: 172), ages 10–17, with bipolar depression | RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT | Lurasidone (10–20 mg/day for 10–14-year-olds; 20–40 mg/day for 15–17-yr-olds) × 6 wks. | Significant improvement in depressive symptoms on the CDRS-R and CGI-BP-S. ↑ response rates on CDRS-R for lurasidone. | Lurasidone has shown significant efficacy in ↓ symptoms of bipolar depression in children and adolescents compared to placebo. Safety profile acceptable; common side effects of nausea and somnolence. Akathisia less than with placebo. No cognitive or metabolic concerns. |

| Singh et al., 2020 [25] | 347 patients (ages 10–17) with DSM-5 bipolar I depression | Post hoc of an RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (DelBello et al., 2017 [19]) | Lurasidone monotherapy, flexibly dosed 20–80 mg/day vs. placebo. Initial dose 20 mg/die. No adjunct mood stabilizers/antidepressants allowed. | Change in CDRS-R total score at wk 6. Change in CGI-BP-S, YMRS, PARS, CGAS, and PQ-LES-Q. | Lurasidone was effective in ↓ depressive symptoms in adolescents, regardless of the presence of mixed features. Safety profile comparable to placebo. |

| DelBello et al., 2021 [26] | 306 participants (aged 10–17 years) with bipolar I depression | Double-blind RCT, placebo-controlled lurasidone trial, extension trial to 104 wks | Flexible-dose lurasidone 20–80 mg/day × 104 wks, starting at 40 mg/day for 1 wk, adjusted weekly for efficacy/tolerability. Mean dose: 52.1 mg/day. Concomitant benzodiazepines (16.7%) and stimulants (15.4%). | Long-term safety and tolerability (adverse events, metabolic parameters, extrapyramidal symptoms). Effectiveness on depressive symptoms (CDRS-R) and global functioning over 104 weeks. | Lurasidone was safe, well tolerated, and effective over 2 years in youth with bipolar depression. Low discontinuation, minimal metabolic or prolactin effects, low akathisia and extrapyramidal symptom rates, and sustained improvement in depressive symptoms and functioning. |

| Kadakia et al., 2021 [35] | 16,201 pediatric patients (≤17 years) with DSM-5 bipolar disorder | Retrospective pharmacoeconomic cohort study | Oral atypical antipsychotics: lurasidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone. | All-cause hospitalization (any inpatient stay). Psychiatric hospitalization (any hospitalization with a psychiatric diagnosis, including bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, ADHD, adjustment disorder, disruptive behavior, and other mental health conditions). | Lurasidone associated with a significantly ↓ risk of all-cause and psychiatric hospitalizations compared to aripiprazole and olanzapine, but not quetiapine or risperidone, suggesting a favorable real-world hospitalization profile for pediatric bipolar care. |

| Diao et al., 2022 [36] | 61 10–17-yr-olds (lurasidone, n = 29 [6 ♂, 23 ♀, mean age, 14]; quetiapine, n = 32 [10 ♂, 22 ♀, mean age, 15]), age p < 0.035 | Prospective longitudinal double-blind RCT | Lurasidone (20 mg/day gradually titrated to 60 mg/day in 1 wk) vs. quetiapine (100 mg/day gradually titrated to 300 mg/day in 1 wk) × 8 wks. | Primary outcome: cognitive performance (THINC Integrated Tool); secondary outcomes: response/remission rates in depressive symptoms (HAM-D ≥ 50%↓ score from BL and <final score ≤ 7, respectively), metabolic measures. | At the 8-wk FU, the two drugs did not differ in any of the measures assessed. There was a high attrition rate, with only 31 completers. |

| Singh et al., 2023 [37] | 347 patients (ages 10–17) with DSM-5 bipolar I depression | Post hoc of an RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (DelBello et al., 2017 [18]) | Lurasidone monotherapy, doses of between 20 and 80 mg/day, or placebo, once daily for 6 weeks. All completers entered a 2-year open-label lurasidone extension. | Changes in depressive and manic symptom clusters (CDRS-R, YMRS) and global functioning (CGAS). Changes in rates of symptomatic remission (CDRS-R ≤ 28) and functional remission (CGAS ≥ 71) over time. Focus on “bridge” symptoms (decreased need for sleep, irritability) influencing outcomes. | Lurasidone improved sleep disturbance and irritability and overall depression, particularly in patients with sleep disturbance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koukopoulos, A.; Calderoni, C.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Callovini, T.; Moccia, L.; Montanari, S.; Autullo, G.; Simonetti, A.; Pinto, M.; Camardese, G.; et al. Lurasidone for Pediatric Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18070979

Koukopoulos A, Calderoni C, Kotzalidis GD, Callovini T, Moccia L, Montanari S, Autullo G, Simonetti A, Pinto M, Camardese G, et al. Lurasidone for Pediatric Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(7):979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18070979

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoukopoulos, Alexia, Claudia Calderoni, Georgios D. Kotzalidis, Tommaso Callovini, Lorenzo Moccia, Silvia Montanari, Gianna Autullo, Alessio Simonetti, Mario Pinto, Giovanni Camardese, and et al. 2025. "Lurasidone for Pediatric Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 7: 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18070979

APA StyleKoukopoulos, A., Calderoni, C., Kotzalidis, G. D., Callovini, T., Moccia, L., Montanari, S., Autullo, G., Simonetti, A., Pinto, M., Camardese, G., Sani, G., & Janiri, D. (2025). Lurasidone for Pediatric Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals, 18(7), 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18070979