Abstract

Background/Objectives: Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has a long history and is known for its anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and immunoregulatory qualities. It has been extensively studied during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, to evaluate the relationship between TCM and the treatment of COVID-19, we conducted a meta-analysis. Methods: Our meta-analysis included 22 randomized clinical trials, which investigated the analyzed endpoints: time to recovery from fever, severity of dyspnea or breathlessness according on different scales, time to recovery for coughing, including dry and wet coughing, time to recovery for fatigue, changes in respiratory rate, length of hospitalization, hospital discharging rate, number of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, number of cases requiring any supplemental oxygenation, number of deaths among COVID-19 patients, conversion rate of SARS-CoV-2 tests on a particular day, and time to viral assay conversion. The relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and the mean difference or standardized mean difference with 95% CIs were calculated to compare the effect. A random effects model was used to calculate effect sizes. Results: We indicated a positive effect of TCM on different COVID-19 symptoms. TCM influences hospitalization duration, ICU admission, mortality, and time to viral assay conversion among COVID-19 patients. Moreover, TCM positively affects SARS-CoV-2 test conversion rates on particular days (RR = 1.21; 95% CI [1.10; 1.32]; p < 0.0001; I2 = 84%). Conclusions: TCM may potentially support the standard treatment of COVID-19. Nevertheless, the necessity for further randomized trials with a greater number of participants and in a wider range of countries remains apparent.

1. Introduction

One of the earliest civilizations in the world was the Chinese. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has undergone a long process of development through the accumulation of practical experience, and its theory is constantly being refined. Despite the fact that it is practiced in many countries and has been suggested to have great potential for improving people’s health and well-being, there are still questions about its effectiveness. It was believed that the TCM theory was difficult to prove using modern scientific methods [1]. TCM traditionally consists of a number of different herbs or compounds with known or unknown active ingredients, which can be used for a variety of medical indications and are tailored to a person’s symptoms. Over the course of China’s long history, TCM has proven itself to treat infectious diseases and has been used to treat pandemic and endemic diseases. For example, during the 2002–2003 SARS-CoV outbreak in China, the use of TCM resulted in shorter hospitalization, reduced side effects of steroid treatment, and relief of breathlessness and malaise. It has been demonstrated that TCM exerts antiviral properties against a range of viral strains, including influenza virus, herpes simplex virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and hepatitis B and C viruses, as well as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [2].

According to TCM, there are two ideological concepts that serve as fundamental tenets. The first is the notion of homeostasis, which emphasizes the integrity of the human body and underscores the symbiotic relationship between the human organism and its social and natural environment. The second is the concept of dynamic balance, which prioritizes movement within integrity. In addition, TCM has its own unique understanding of the human body as well as disorders of the human body [3]. Herbal Chinese medicine dates back to the discovery of “Ma Huang” (herba ephedrae) around 3000 BC, which among other things was used to treat respiratory disorders [4]. Among the 12,807 types of Chinese medical materials, there are 11,146 types of plant medicine, 1581 types of animal medicine, 5000 types of Chinese patent medicine, 80 types of mineral medicine, and more than one million prescriptions. In addition to herbal medicine, there is Acu-moxa therapy (“zhen jiu”), which includes several techniques aimed at stimulating acupuncture points located on the body along circulatory pathways or conduits. The most popular of these techniques are acupuncture and moxibustion [5].

TCM has been found to have anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and immunoregulatory properties [6]. Active ingredients in TCM formulations that are effective in treating COVID-19 were identified using network pharmacology analysis. For example, it has the ability to target Mpro (SARS-CoV-2 3CL hydrolase), the main protease for SARS-CoV-2, or ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2), the receptor for SARS-CoV-2, which may inhibit the development of COVID-19 [2,6]. In the context of the efforts to combat the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in China, TCM has been formally incorporated into the third to eighth editions of the diagnostic and treatment guidelines promulgated by the National Health Commission of China [2]. Therefore, we decided to conduct a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate the relationship between TCM and the treatment of COVID-19.

2. Results

2.1. Search Results

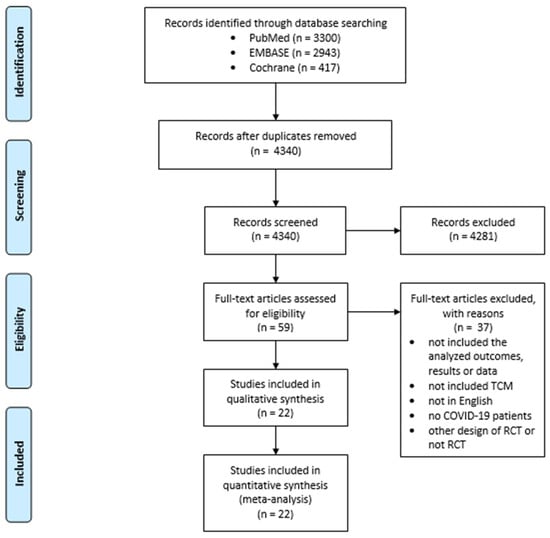

The literature search yielded a total of 4340 articles, subsequent to the removal of duplicates (Figure 1). During the first screening process, 4281 articles were excluded on the basis of their categorization as meta-analyses, systematic reviews, literature reviews, editorial letters, in vitro studies, studies on animals, case reports, and observational studies. Furthermore, articles written in languages other than English were excluded. Following the full-text screening, 22 articles were deemed eligible for meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Selection of studies for meta-analysis.

All included studies are randomized controlled trials with control groups, investigating the effect of TCM in COVID-19 treatment, which were carried out in China [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], except one study from Iran [28]. Three studies had placebos in the control group [21,22,26], and one study had a compound pholcodine oral solution in the control group [20]. Most of the studies had standard treatment in the control group and standard treatment with TCM in the experimental group [7,8,9,10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,23,24,25,27,28]. In the study by Yu et al. [11], we considered the group that received Paxlovid (300 mg of Nirmatrelvir plus 100 mg of Ritonavir) as the control group, and the other 2 groups as experimental. Two studies included pediatric patients [20,24]. The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1, while Table S1 shows the detailed description and formulas of TCM in the included studies.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of included studies.

2.2. Quality Evaluation

The risk of bias was determined for 22 included studies. Ten of the studies have a high risk of bias, while twelve indicate low risk. Figure S1 shows the summary of the risk of bias assessment.

2.3. Effect of TCM on Systemic and Respiratory Symptoms of COVID-19 and Changes in Respiratory Rate

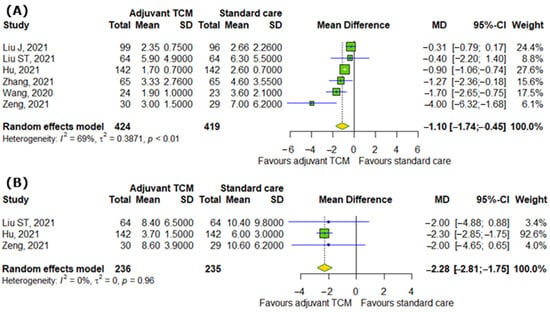

We analyzed the effect of TCM on symptoms of COVID-19 and changes in respiratory rate. Our analyzed showed the significant differences between interventional and control groups in systemic symptoms, such as time to recovery of fever (MD = −1.1; 95% CI [−1.74; −0.45]; p = 0.0009; I2 = 69%) and time to recovery for fatigue (MD = −2.28; 95% CI [−2.81; −1.75]; p < 0.0001; I2 = 0%), as represented in Figure 2A,B.

Figure 2.

In comparison to standard COVID-19 treatment, the addition of traditional Chinese medicine to standard COVID-19 treatment affects systemic symptoms of COVID-19 by reducing (A) time to recovery from fever and (B) time to recovery from fatigue [8,9,13,16,17,25].

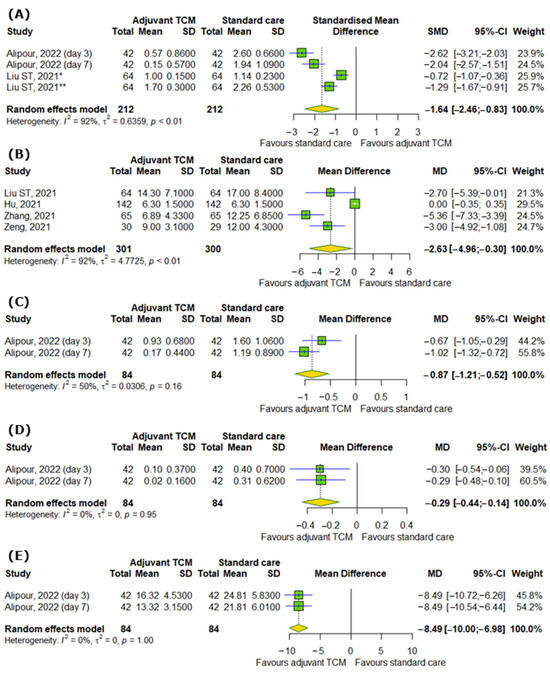

In the case of respiratory symptoms, there were also significant differences between interventional and control groups, for example, the severity of dyspnea or breathlessness according to different scales (SMD = −1.64; 95% CI [−2.46; −0.83]; p < 0.0001; I2 = 92%); time to recovery for coughing (MD = −2.63; 95% CI [−4.96; −0.3]; p = 0.0272; I2 = 92%), including dry (MD = −0.87; 95% CI [−1.21; −0.52]; p < 0.0001; I2 = 50%) and wet coughing (MD = −0.29; 95% CI [−0.44; −0.14]; p = 0.0001; I2 = 0%); and changes in respiratory rate (MD = −8.49; 95% CI [−10.0; −6.98]; p < 0.0001; I2 = 0%), as represented in Figure 3A–E.

Figure 3.

In comparison to standard COVID-19 treatment, the addition of traditional Chinese medicine to standard COVID-19 treatment affects respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 by reducing (A) the severity of dyspnea or breathlessness according to different scales, (B) time to recovery for coughing, including (C) dry and (D) wet coughing, and (E) respiratory rate [28]. * Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale; ** modified Borg dyspnea scale.

2.4. Effect of TCM on COVID-19 Hospitalization

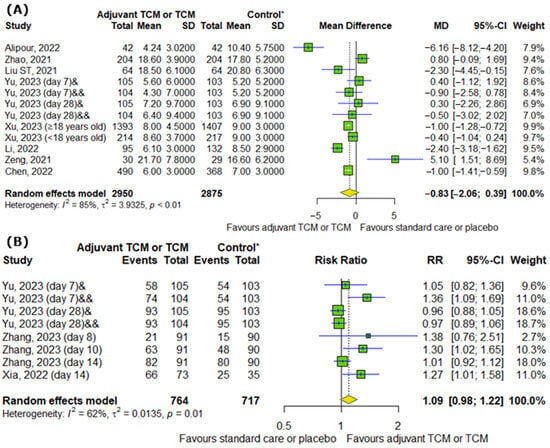

We analyzed the effect of TCM on COVID-19 hospitalization. Figure 4A showed that there are no differences between experimental and control groups in hospitalization duration (MD = −0.83; 95% CI [−2.06; 0.39]; p = 0.1827; I2 = 85%). Moreover, TCM did not significantly influence the discharge rates of hospitalized patients on particular days (RR = 1.09; 95% CI [0.98; 1.22]; p = 0.0962; I2 = 62%), as shown in Figure 4B.

Figure 4.

In comparison to standard COVID-19 treatment or placebo, the addition of traditional Chinese medicine to standard COVID-19 treatment or only TCM does not affect (A) COVID-19 hospitalization duration and (B) the discharge rates of COVID-19 patients on particular days [7,9,11,15,18,22,23,25,26,28]. * standard care or placebo; & Huashi Baidu; && Huashi Baidu and Paxlovid.

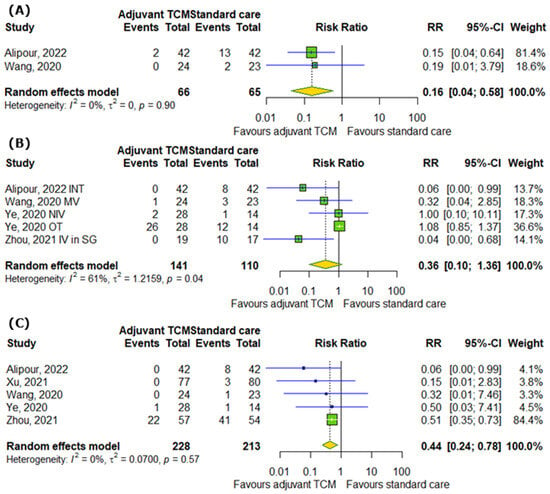

2.5. Effect of TCM on Number of ICU Admissions, Number of Cases Requiring Any Supplemental Oxygenation and Number of Deaths Among COVID-19 Patients

When it comes to the influence of TCM on the number of ICU admissions, the number of cases requiring any supplemental oxygenation, and the number of deaths among COVID-19 patients, our analysis demonstrated that TCM can reduce the risk of ICU admission by 84% (RR = 0.16; 95% CI [0.04; 0.58]; p = 0.0053; I2 = 0%) and the risk of death by 56% (RR = 0.44; 95% CI [0.24; 0.78]; p = 0.0052; I2 = 0%), but non-significantly reduces the risk of requiring any supplemental oxygenation (RR = 0.36; 95% CI [0.1; 1.36]; p = 0.1318; I2 = 61%) (Figure 5A–C).

Figure 5.

In comparison to standard COVID-19 treatment, the addition of traditional Chinese medicine to standard COVID-19 treatment improves (A) the number of ICU admissions, does not affect (B) the number of cases requiring any supplemental oxygenation, and decreases (C) the number of deaths among COVID-19 patients [14,17,19,27,28]. INT—intubation; MV—mechanical ventilation; NIV—non-invasive ventilation; OT—oxygen therapy; IV in SG—an invasive ventilator in the severe group.

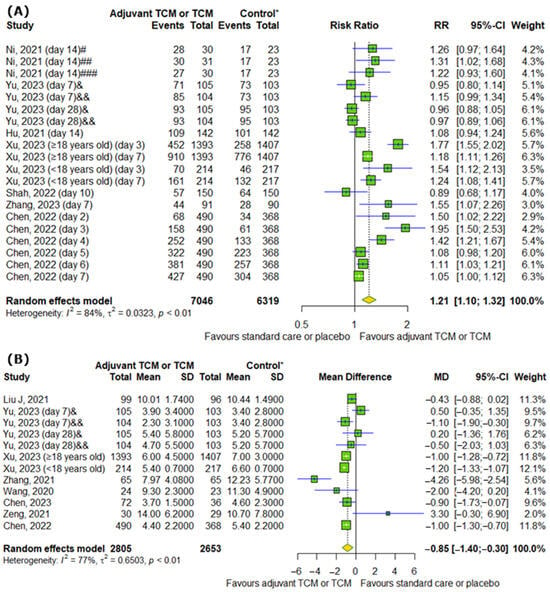

2.6. Effect of TCM on Conversion Rate of SARS-CoV-2 Tests on Particular Days and Time to Viral Assay Conversion

Interestingly, TCM positively affects the conversion rate of SARS-CoV-2 tests on particular days (RR = 1.21; 95% CI [1.10; 1.32]; p < 0.0001; I2 = 84%) (Figure 6A). Moreover, we detected differences between analyzed groups in time to viral assay conversion (MD = −0.85; 95% CI [−1.4; −0.3]; p = 0.0025; I2 = 77%) (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

In comparison to standard COVID-19 treatment or placebo, the addition of traditional Chinese medicine to standard COVID-19 treatment or only TCM affects SARS-CoV-2 tests by increasing (A) the conversion rate of SARS-CoV-2 tests on particular days and by reducing (B) the time to viral assay conversion [8,10,11,13,15,16,17,20,21,23,25,26]. * standard care or placebo; # low-dose group; ## middle-dose group; ### high-dose group; & Huashi Baidu; && Huashi Baidu and Paxlovid.

2.7. Publication Bias

Figure S2 shows the funnel plots for all investigated outcomes, such as time to recovery from fever, severity of dyspnea or breathlessness according to different scales, time to recovery for coughing, including dry and wet coughing, time to recovery for fatigue, changes in respiratory rate, length of hospitalization, hospital discharging rate, number of ICU admissions, number of cases requiring any supplemental oxygenation, number of deaths among COVID-19 patients, conversion rate of SARS-CoV-2 test on particular days, and time to viral assay conversion. Additionally, we performed Peters’ regression test and Egger’s regression test to calculate publication biases for these outcomes. The results showed that there was no evidence of publication bias for the association between TCM and time to recovery from fever (p = 0.5081), time to recovery for coughing (p = 0.0874), length of hospitalization (p = 0.8311), hospital discharging rate (p = 0.5634), number of cases requiring any supplemental oxygenation (p = 0.7809), number of deaths (p = 0.8462), conversion rate of SARS-CoV-2 tests on particular days (p = 0.3513), and time to viral assay conversion (p = 0.2534). However, publication bias can occur between TCM and severity of dyspnea or breathlessness according to different scales (p = 0.0343) and time to recovery for fatigue (p = 0.0340). Tests for other outcomes could not be calculated because too few studies were included.

3. Discussion

We have carried out a meta-analysis of data collected from 22 randomized clinical trials and demonstrated a positive effect of TCM on COVID-19 symptoms, namely time to recovery from fever, severity of dyspnea or breathlessness according to different scales, time to recovery for coughing, including dry and wet coughing, time to recovery for fatigue, and changes in respiratory rate. Moreover, TCM influences hospitalization duration, ICU admission, mortality, and time to viral assay conversion among COVID-19 patients. Interestingly, TCM positively affected the conversion rate of SARS-CoV-2 tests on particular days. However, TCM did not significantly affect the discharge rates of hospitalized patients on particular days or the requirement of any type of supplemental oxygenation among participants. Of note, our data are consistent with data provided by researchers carrying out similar studies.

In terms of the general efficiency of TCM as a supplementary treatment alongside conventional drugs, most of the studies are univocal. A number of studies report a positive effect of TCM. A network meta-analysis showed that the Maxing Shigan decoction in combination with conventional treatment was more successful in COVID-19 treatment than the conventional treatment [29]. Another study showed that a combination of Chinese herbal medicine and conventional anti-COVID-19 treatment resulted in improvements in multiple parameters related to lungs, fever, COVID-19 severity, and antiviral immune response, in comparison to conventional treatment alone [30]. Similar results were obtained by a number of authors as the addition of varying forms of herbal TCM treatment alleviated COVID-19 symptoms including cough, fever, and fatigue, as well as hampered progression of the disease [31,32,33,34]. On the other hand, some authors reported that subsequent implementation of TCM and conventional treatment improves therapy efficiency and chest CT results, and decreases disease severity, but lacks impacts on COVID-19-associated fever [35]. Interestingly, some authors report that despite some evidence of benefits of TCM in COVID-19 treatment accompanied by relative safety of this approach is apparent. However, the analyzed studies may be affected by a high risk of bias, and include too-small numbers of participants in order to be clinically relevant, and more reliable studies are required to draw a conclusion [36,37].

More evidence of the potentially beneficial effects of TCM in COVID-19 patients can be found in observational studies. In a multicenter, prospective observational study, Hua et al. [38] showed that a kumquat decoction containing kumquat, jiegeng (Platycodonis radix) and two other Chinese herbs was correlated with faster cough relief in comparison to the control group. In a group with moderate COVID-19, without cough and dyspnea symptoms, administration of a Chinese herbal decoction—a mixture of 11 herbs—resulted in quicker viral clearance, measured by negative PCR test results [39]. Furthermore, the efficiency of some TCM approaches has been shown in a number of studies conducted in severely and critically ill COVID-19 patients based on systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies [40]. Administration of Shenhuang Granule, which comprises Panax ginseng C. A. Mey, Rheum palmatum L. stem, Sargentodoxa cuneata stem, Taraxacum mongolicum, Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata, and Whitmania pigra, in addition to the standard therapy, decreased mortality, the time patients spent in the ICU, and the need for mechanical ventilation, as observed in an observational study in 118 people [41]. In a retrospective cohort study, reduced COVID-19 mortality was also observed by another group of researchers who treated severely and critically ill COVID-19 patients with a TCM decoction, where 94 people were selected for both groups [42]. To date, obtained results may suggest that the administration of TCM might be beneficial, regardless of COVID-19 severity, although due to the high probability of bias in randomization processes and small test populations, the results may not be reliable, and further research on the topic is required [40].

Unfortunately, our meta-analysis has some limitations. Firstly, the studies analyzed used different types of TCM, but due to the small number of included studies, they were analyzed together, as it was not possible to perform subgroup analyses. This may have affected the interpretation of the results and the high heterogeneity of the analyses. Secondly, only one study was conducted outside China, which may have affected the bias of the results. Thirdly, the study included participants with varying degrees of COVID-19 severity, which may also affect the heterogeneity of the analyzed data. In addition, the herbs used in TCM could potentially interact with standard COVID-19 therapy, which could affect treatment. All of this could have affected the interpretation of the results. Taking into consideration the abovementioned results of our study, data presented by other authors of meta-analyses, and finally observational studies, the efficiency of TCM looks promising in the treatment of COVID-19. Moreover, by integrating TCM with standard medicine, the treatment period can be shortened, thereby leading to a reduction in healthcare costs for patients. Despite that, we believe, similarly to many other authors, that further research on the topic is required. The conclusion may be supported by recommendations of the WHO that originated from the “WHO Expert Meeting on Evaluation of TCM in the Treatment of COVID-19” [43], where the experts considered up-to-date evidence on the efficiency of TCM in COVID-19 management. The experts highlighted the need for further research, including improving the analysis of data already collected and, most importantly, the need for new, reliable clinical trials. The experts stated that well-planned studies that include properly assessed key factors such as sample size, randomization, and blinding are required. Notably, the trials should be based on the worldwide cooperation of WHO Member States, including hospitals outside of China.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Search Strategy

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [44]. Databases such as PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched. Literature published until 5 April 2024 was included. The following keywords were used: “Traditional Chinese medicine”, “acupuncture”, “moxibustion”, “cupping”, “tai chi”, “Chinese herbal medicine”, “COVID-19”, “coronavirus infection”, and “SARS-CoV-2”. The detailed search steps are shown in Table S2.

4.2. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

Inclusion criteria included only articles written in English of RCTs examining the efficacy of TCM only or in addition to COVID-19 treatment compared to placebo or standard care in the treatment of COVID-19. Articles should have been published before 5 April 2024 and included the following endpoints: time to recovery from fever, severity of dyspnea or breathlessness according to different scales, time to recovery for coughing, including dry and wet coughing, time to recovery for fatigue, changes in respiratory rate, length of hospitalization, hospital discharging rate, number of ICU admissions, number of cases requiring any supplemental oxygenation, number of deaths among COVID-19 patients, conversion rate of SARS-CoV-2 tests on particular days, and time to viral assay conversion. Exclusion criteria were as follows: articles not written in English and not containing the endpoints.

Continuous data were converted into means (SD):

- If the data were presented as a median with quartiles [median (Q1, Q3)] or a median (range), the value was converted according to the method presented by Luo et al. [45] and Wan et al. [46] using available calculators without checking the skewness.

- If the data were presented as a mean (95% confidence intervals), the value was converted according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [47] using the formula

If the number of cases was a percentage, it was converted to whole numbers in accordance with rounding rules.

4.3. Quality Evaluation

The quality of trials was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials [48]. The following criteria were used: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias (assessing at 3 levels such as low, high, or unclear risk).

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of data was performed in R (version 4.2.2). To compare the effects of TCM on COVID-19 in the experimental group compared with the control group, the relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated for dichotomous outcomes, while mean differences or standardized mean differences with 95% CIs were calculated for continuous outcomes. A random effects model was utilized to calculate effect sizes. I2 statistics were employed to assess the heterogeneity among the studies: I2 < 40% may not be important; 30% < I2 < 60% means moderate heterogeneity; 50% < I2 < 90% means substantial heterogeneity; I2 > 75% means considerable heterogeneity [49]. To assess publication bias, funnel plots, Peters’ regression test (for dichotomous outcomes), and Egger’s regression test (for continuous outcomes) were used. The results of this meta-analysis were deemed to be statistically significant at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of our study suggest that traditional Chinese medicine may be beneficial when used in combination with conventional treatment for SARS-CoV-2. However, the lack of high-quality clinical trials, difficulties in standardizing the therapy, and possible drug interactions mean that its effectiveness remains uncertain. It should be noted that further randomized, controlled trials with larger sample sizes and from more countries are needed to provide more robust evidence to support this hypothesis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ph18030357/s1, Table S1: Detailed description and TCM formulas used in the included studies. Figure S1: Risk of bias of included studies. Figure S2: Funnel plots for the associations between traditional Chinese medicine and COVID-19. Table S2: Search strategy in PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.; methodology, M.S.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, R.P.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, R.P.; project administration, R.P.; funding acquisition, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Medical University of Lodz, grant number [503/0-149-03/503-01-001]. The APC was funded by the Medical University of Lodz.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TCM | Traditional Chinese medicine |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| RR | Relative risk |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

References

- Liu, S.; Zhu, J.-J.; Li, J.-C. The Interpretation of Human Body in Traditional Chinese Medicine and Its Influence on the Characteristics of TCM Theory. Anat. Rec. 2021, 304, 2559–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Youn, J.Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Cai, H. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in the Treatment of COVID-19 and Other Viral Infections: Efficacies and Mechanisms. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 225, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.-P.; Jia, H.-W.; Xiao, C.; Lu, Q.-P. Theory of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Therapeutic Method of Diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 1854–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, L.C.; Machado, J.P.; Monteiro, F.J.; Greten, H.J. Understanding Traditional Chinese Medicine Therapeutics: An Overview of the Basics and Clinical Applications. Healthcare 2021, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Wang, S.; Shi, Y.; Ni, S.; Tang, M.; Xu, A. The Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Sci. 2021, 8, S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.-J.; Wan, S.-Y.; Gong, S.-S.; Liu, J.-C.; Li, F.; Kou, J.-P. Recent Advances of Traditional Chinese Medicine on the Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 18, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, L.; Yang, W.; Lv, W.; Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Dong, Y.; Shi, N.; Lu, C.; Li, Z.; et al. Chinese Medicine Formula Huashibaidu Granule Early Treatment for Mild COVID-19 Patients: An Unblinded, Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 696976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Lu, C.; Ruan, L.; Zhao, C.; Huo, R.; Shen, X.; Miao, Q.; Lv, W.; et al. Combination of Hua Shi Bai Du Granule (Q-14) and Standard Care in the Treatment of Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Single-Center, Open-Label, Randomized Controlled Trial. Phytomedicine 2021, 91, 153671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-T.; Zhan, C.; Ma, Y.-J.; Guo, C.-Y.; Chen, W.; Fang, X.-M.; Fang, L. Effect of Qigong Exercise and Acupressure Rehabilitation Program on Pulmonary Function and Respiratory Symptoms in Patients Hospitalized with Severe COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Integr. Med. Res. 2021, 10, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Wen, Z.; Hu, X.; Tang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, L.; Wu, L.; Wang, H.; Xu, C.; Xu, X.; et al. Effects of Shuanghuanglian Oral Liquids on Patients with COVID-19: A Randomized, Open-Label, Parallel-Controlled, Multicenter Clinical Trial. Front. Med. 2021, 15, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, B.; Lv, J.; Zhu, X.; Shang, B.; Xv, Y.; Tao, R.; Yang, Y.; Cong, J.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Huashi Baidu Granule plus Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir Combination Therapy in Patients with High-Risk Factors Infected with Omicron (B.1.1.529): A Multi-Arm Single-Center, Open-Label, Randomized Controlled Trial. Phytomedicine 2023, 120, 155025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, L.; Xu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Jiang, R.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Shang, H.; Lian, B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Lianhua Qingke Tablets in the Treatment of Mild and Common-Type COVID-19: A Randomized, Controlled, Multicenter Clinical Study. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 8733598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Guan, W.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Q.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Duan, Z.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Lianhuaqingwen Capsules, a Repurposed Chinese Herb, in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Multicenter, Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C.; Su, H.; Zhao, L.; Xue, L.; Hu, F.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Reduning Injection in the Treatment of COVID-19: A Randomized, Multicenter Clinical Study. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 5146–5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, S.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Jin, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, G.; Cao, M.; Sun, D.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Reyanning Mixture in Patients Infected with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant: A Prospective, Open-Label, Randomized Controlled Trial. Phytomedicine 2023, 108, 154514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, L.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, L.; Xu, Q.; Zou, X.; Ding, Y.; Tian, J.; Fan, J.; Fan, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Xiyanping Injection in the Treatment of COVID-19: A Multicenter, Prospective, Open-label and Randomized Controlled Trial. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 4401–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Jing, J.; Zhao, P.; Dong, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, G.; Niu, M.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, T.; et al. Exploring an Integrative Therapy for Treating COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 26, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, D.; Gao, X.; Ju, M.; Fang, H.; Yan, Z.; Qu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, L.; Weng, H.; et al. Ginger Supplement Significantly Reduced Length of Hospital Stay in Individuals with COVID-19. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 19, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y. Guideline-Based Chinese Herbal Medicine Treatment Plus Standard Care for Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 (G-CHAMPS): Evidence From China. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, S.; Chen, J.; Shen, S.; Wang, D.; Lin, J.; Dong, H.; Yin, Y.; et al. Huashi Baidu Granule in the Treatment of Pediatric Patients with Mild Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Single-Center, Open-Label, Parallel-Group Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1092748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.R.; Fatima, S.; Khan, S.N.; Ullah, S.; Himani, G.; Wan, K.; Lin, T.; Lau, J.Y.N.; Liu, Q.; Lam, D.S.C. Jinhua Qinggan Granules for Non-Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, and Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 928468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Lei, W.; Shen, J.; Lu, J.; Tao, T.; Cao, X.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J.; Shi, C. Oral Liushen Pill for Patients with COVID-19: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Pulm. Circ. 2023, 13, e12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, W.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, J.; Huang, M.; Li, Q.; Duan, C.; Li, Z.; Fan, C.; Zou, Y.; Xu, B.; et al. Randomized Controlled Study of a Diagnosis and Treatment Plan for Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019 That Integrates Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2022, 42, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, S.; Jin, G.; Wu, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Peng, W.; Zhang, W.; Sun, D.; Fang, B. Reyanning Mixture on Asymptomatic or Mild SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children and Adolescents: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2023, 29, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Yuan, Z.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Ye, R.; Cheng, J. Therapeutic Effects of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Maxingshigan-Weijing Decoction) on COVID-19: An Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial. Integr. Med. Res. 2021, 10, 100782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Geng, P.; Shen, J.; Liangpunsakul, S.; Lyu, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Dong, C.; et al. Traditional Chinese Medicine JingYinGuBiao Formula Therapy Improves the Negative Conversion Rate of SARS-CoV2 in Patients with Mild COVID-19. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5641–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Feng, J.; Xie, Q.; Huang, T.; Xu, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, W.; Sun, S.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; et al. Traditional Chinese Medicine Shenhuang Granule in Patients with Severe/Critical COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Multicenter Trial. Phytomedicine 2021, 89, 153612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alipour, R.; Jamalimoghadamsiahkali, S.; Karimi, M.; Asadi, A.; Ghaem, H.; Adel-Mehraban, M.S.; Kazemi, A.H. Acupuncture or Cupping plus Standard Care versus Standard Care in Moderate to Severe COVID-19 Patients: An Assessor-Blinded, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Integr. Med. Res. 2022, 11, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Lin, Y.; He, F.; Jin, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, T.; Wu, C.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X. Identification of Active Compounds of Traditional Chinese Medicine Derived from Maxing Shigan Decoction for COVID-19 Treatment: A Meta-Analysis and in Silico Study. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2023, 21, 871–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Shi, L.; Cao, W.; Zuo, B.; Zhou, A. Add-on Effect of Chinese Herbal Medicine in the Treatment of Mild to Moderate COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jiang, Y.; Yue, B.; Luan, L. Use of Traditional Chinese Medicine as an Adjunctive Treatment for COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e26641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.Y.; Gu, S.; Alemi, S.F. Chinese Herbal Medicine for COVID-19: Current Evidence with Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 18, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Xie, R.; Pakhale, S.; Krewski, D.; Cameron, D.W.; Wen, S.W. The Effects of Traditional Chinese Medicine as an Auxiliary Treatment for COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2021, 27, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Xu, N.; Zhou, Y.; Song, J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, R. Contribution of Traditional Chinese Medicine Combined with Conventional Western Medicine Treatment for the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), Current Evidence with Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 5992–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Guan, H.; Xin, W.; Yang, B.-C. A Meta-Analysis of 13 Randomized Trials on Traditional Chinese Medicine as Adjunctive Therapy for COVID-19: Novel Insights into Lianhua Qingwen. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 4133610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Greenhalgh, T.; Wardle, J. Chinese Herbal Medicine (“3 Medicines and 3 Formulations”) for COVID-19: Rapid Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2022, 28, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Li, M.; Tian, C.; Lai, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, J.; Shi, N.; Zhao, H.; Yang, K.; Shang, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Chinese Herbal Medicine for Treating Mild or Moderate COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials and Observational Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 988237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Q.; Tang, L.; Shui, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Xu, X.; Yang, C.; Gao, W.; Liao, G.; Liu, Q.; et al. Effectiveness of Kumquat Decoction for the Improvement of Cough Caused by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variants, a Multicentre, Prospective Observational Study. Phytomedicine 2023, 120, 155008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Gao, X.; Liu, M. Benefits from Shortening Viral Shedding by Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment for Moderate COVID-19: An Observational Study. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 7179050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, J.; Shi, N.; Li, L.; Yang, K.; et al. Role of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Treating Severe or Critical COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Observational Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 926189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Fang, B.; Zhou, D.; Wang, J.; Zou, D.; Yu, G.; Fen, Y.; Peng, D.; Hu, J.; Zhan, D. Clinical Effect of Traditional Chinese Medicine Shenhuang Granule in Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19: A Single-Centered, Retrospective, Observational Study. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.-G.; An, X.-D.; Xie, P.; Jiang, B.; Tian, J.-X.; Yang, Q.; Li, X.-Y.; Luo, M.; Liu, P.; Zhao, S.-H.; et al. Traditional Chinese Medicine Decoctions Significantly Reduce the Mortality in Severe and Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2021, 49, 1063–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Expert Meeting on Evaluation of Traditional Chinese Medicine in the Treatment of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-expert-meeting-on-evaluation-of-traditional-chinese-medicine-in-the-treatment-of-covid-19 (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Wan, X.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Optimally Estimating the Sample Mean from the Sample Size, Median, Mid-Range, and/or Mid-Quartile Range. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2018, 27, 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Estimating the Sample Mean and Standard Deviation from the Sample Size, Median, Range and/or Interquartile Range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 6.4 (Updated August 2023); Cochrane: London, UK, 2023.

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, J.J.; Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G. Analysing Data and Undertaking Meta-Analyses. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Higgins, J.P., Green, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2008; pp. 243–296. ISBN 978-0-470-71218-4. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).