Serum and Glucocorticoid-Inducible Kinase 1 (SGK1) in NSCLC Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The SGK Protein Family

3. Mouse Models to Elucidate SGK Protein Functions

4. SGK1 Expression

5. SGK1 Is a Predicted Target of microRNAs Relevant in NSCLC

6. SGK1 Is a Prognostic Factor in NSCLC

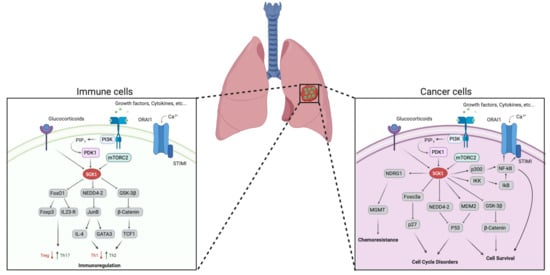

7. Potential Targeting of SGK1 in Combination with Chemotherapy to Treat NSCLC

8. Potential Targeting of SGK1 in Combination with Immune-Therapy to Treat NSCLC

9. SGK1 Inhibitors

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inamura, K. Lung Cancer: Understanding Its Molecular Pathology and the 2015 WHO Classification. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travis, W.D.; Brambilla, E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Yatabe, Y.; Austin, J.H.M.; Beasley, M.B.; Chirieac, L.R.; Dacic, S.; Duhig, E.; Flieder, D.B.; et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 1243–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, E.; Morbini, P.; Cancellieri, A.; Damiani, S.; Cavazza, A.; Comin, C.E. Adenocarcinoma classification: Patterns and prognosis. Pathologica 2018, 110, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J.; Cha, Y.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, A.; Kim, E.Y.; Chang, Y.S. Keratinization of Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma Is Associated with Poor Clinical Outcome. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. (Seoul) 2017, 80, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosi, G.; Barbareschi, M.; Cavazza, A.; Graziano, P.; Rossi, G.; Papotti, M. Large cell carcinoma of the lung: A tumor in search of an author. A clinically oriented critical reappraisal. Lung Cancer 2015, 87, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbst, R.S.; Morgensztern, D.; Boshoff, C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature 2018, 553, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Fillmore, C.M.; Hammerman, P.S.; Kim, C.F.; Wong, K.K. Non-small-cell lung cancers: A heterogeneous set of diseases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kwok-Shing Ng, P.; Kucherlapati, M.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y.; Tsang, Y.H.; de Velasco, G.; Jeong, K.J.; Akbani, R.; Hadjipanayis, A.; et al. A Pan-Cancer Proteogenomic Atlas of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway Alterations. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 820–832.e823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millis, S.Z.; Ikeda, S.; Reddy, S.; Gatalica, Z.; Kurzrock, R. Landscape of Phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase Pathway Alterations Across 19784 Diverse Solid Tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, K.M.; Barbie, D.A.; Davies, M.A.; Rabinovsky, R.; McNear, C.J.; Kim, J.J.; Hennessy, B.T.; Tseng, H.; Pochanard, P.; Kim, S.Y.; et al. AKT-independent signaling downstream of oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in human cancer. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castel, P.; Ellis, H.; Bago, R.; Toska, E.; Razavi, P.; Carmona, F.J.; Kannan, S.; Verma, C.S.; Dickler, M.; Chandarlapaty, S.; et al. PDK1-SGK1 Signaling Sustains AKT-Independent mTORC1 Activation and Confers Resistance to PI3Kalpha Inhibition. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, E.M.; Dry, H.; Cross, D.; Guichard, S.; Davies, B.R.; Alessi, D.R. Elevated SGK1 predicts resistance of breast cancer cells to Akt inhibitors. Biochem. J. 2013, 452, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matikas, A.; Mistriotis, D.; Georgoulias, V.; Kotsakis, A. Current and Future Approaches in the Management of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients With Resistance to EGFR TKIs. Clin. Lung Cancer 2015, 16, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.H.; Lu, J.J. Osimertinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cancer Lett. 2018, 420, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciuti, B.; De Giglio, A.; Mecca, C.; Arcuri, C.; Marini, S.; Metro, G.; Baglivo, S.; Sidoni, A.; Bellezza, G.; Crino, L.; et al. Precision medicine against ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer: Beyond crizotinib. Med. Oncol. 2018, 35, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, S.; Ashraf, Z.; Lee, K.; Latif, M. First macrocyclic 3(rd)-generation ALK inhibitor for treatment of ALK/ROS1 cancer: Clinical and designing strategy update of lorlatinib. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 134, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchard, D.; Smit, E.F.; Groen, H.J.M.; Mazieres, J.; Besse, B.; Helland, A.; Giannone, V.; D’Amelio, A.M., Jr.; Zhang, P.; Mookerjee, B.; et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously untreated BRAF(V600E)-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: An open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.A.; Hughes, B.G. Targeted therapy for non-small cell lung cancer: Current standards and the promise of the future. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2015, 4, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Peng, S.; Li, P.; Ma, L.; Gan, X. High expression of NEK2 promotes lung cancer progression and drug resistance and is regulated by mutant EGFR. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayatani, H.; Ohashi, K.; Ninomiya, K.; Makimoto, G.; Nishii, K.; Higo, H.; Watanabe, H.; Kano, H.; Kato, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; et al. Beneficial effect of erlotinib and trastuzumab emtansine combination in lung tumors harboring EGFR mutations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Sun, W.; Chen, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, J. Sustained Response to Crizotinib After Resistance to First-Line Alectinib Treatment in Two Patients With ALK-Rearranged NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, e150–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, L.; Doczi, R.; Vodicska, B.; Kormos, D.; Toth, L.; Takacs, I.; Varkondi, E.; Tihanyi, D.; Lakatos, D.; Dirner, A.; et al. Efficacy of Incremental Next-Generation ALK Inhibitor Treatment in Oncogene-Addicted, ALK-Positive, TP53-Mutant NSCLC. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Chen, H. Optimal Care for Patients with Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK)-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Review on the Role and Utility of ALK Inhibitors. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 6615–6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Park, S.; Jung, H.A.; Sun, J.M.; Lee, S.H.; Ahn, J.S.; Park, K.; Ahn, M.J. Evaluating entrectinib as a treatment option for non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Cohen, P. Activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated protein kinase by agonists that activate phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase is mediated by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) and PDK2. Biochem. J. 1999, 339, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Leong, M.L.; Buse, P.; Maiyar, A.C.; Firestone, G.L.; Hemmings, B.A. Serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK) is a target of the PI 3-kinase-stimulated signaling pathway. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 3024–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milburn, C.C.; Deak, M.; Kelly, S.M.; Price, N.C.; Alessi, D.R.; Van Aalten, D.M. Binding of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate to the pleckstrin homology domain of protein kinase B induces a conformational change. Biochem. J. 2003, 375, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Mieulet, V.; Lamb, R.F. mTORC2 is the hydrophobic motif kinase for SGK1. Biochem. J. 2008, 416, e19–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Martinez, J.M.; Alessi, D.R. mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) controls hydrophobic motif phosphorylation and activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1). Biochem. J. 2008, 416, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, R.M.; Kieloch, A.; Currie, R.A.; Deak, M.; Alessi, D.R. The PIF-binding pocket in PDK1 is essential for activation of S6K and SGK, but not PKB. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 4380–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, F.; Bohmer, C.; Palmada, M.; Seebohm, G.; Strutz-Seebohm, N.; Vallon, V. (Patho)physiological significance of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoforms. Physiol. Rev. 2006, 86, 1151–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loffing, J.; Flores, S.Y.; Staub, O. Sgk kinases and their role in epithelial transport. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2006, 68, 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salker, M.S.; Christian, M.; Steel, J.H.; Nautiyal, J.; Lavery, S.; Trew, G.; Webster, Z.; Al-Sabbagh, M.; Puchchakayala, G.; Foller, M.; et al. Deregulation of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1 in the endometrium causes reproductive failure. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1509–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikamp, E.B.; Patel, C.H.; Collins, S.; Waickman, A.; Oh, M.H.; Sun, I.H.; Illei, P.; Sharma, A.; Naray-Fejes-Toth, A.; Fejes-Toth, G.; et al. The AGC kinase SGK1 regulates TH1 and TH2 differentiation downstream of the mTORC2 complex. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tournier, C.; Davis, R.J.; Flavell, R.A. Regulation of IL-4 expression by the transcription factor JunB during T helper cell differentiation. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yu, J.; Xia, T.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, B.; Guo, Y.; Deng, J.; Deng, Y.; Chen, S.; et al. Hepatic serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated protein kinase 1 (SGK1) regulates insulin sensitivity in mice via extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2). Biochem. J. 2014, 464, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Goel-Bhattacharya, S.; Sengupta, S.; Cochran, B.H. A Large-Scale RNAi Screen Identifies SGK1 as a Key Survival Kinase for GBM Stem Cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Stournaras, C. Serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase, metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and tumor growth. Hormones (Athens) 2013, 12, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Leng, T.; Yang, T.; Zeng, Z.; Ueki, T.; Xiong, Z.G. Role of serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinases in stroke. J. Neurochem. 2016, 138, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Gorlach, A.; Vallon, V. Targeting SGK1 in diabetes. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2009, 13, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerli, U.M.; Ullrich, K.; Stuhmer, T.; Holien, T.; Kochert, K.; Holt, R.U.; Bruland, O.; Chatterjee, M.; Nogai, H.; Lenz, G.; et al. Serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1) is a prominent target gene of the transcriptional response to cytokines in multiple myeloma and supports the growth of myeloma cells. Oncogene 2011, 30, 3198–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlacchio, A.; Ranieri, M.; Brave, M.; Arciuch, V.A.; Forde, T.; De Martino, D.; Anderson, K.E.; Hawkins, P.; Di Cristofano, A. SGK1 Is a Critical Component of an AKT-Independent Pathway Essential for PI3K-Mediated Tumor Development and Maintenance. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6914–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhem, A.; Yamada, S.D.; Fleming, G.F.; Delgado, B.; Brickley, D.R.; Wu, W.; Kocherginsky, M.; Conzen, S.D. Administration of glucocorticoids to ovarian cancer patients is associated with expression of the anti-apoptotic genes SGK1 and MKP1/DUSP1 in ovarian tissues. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3196–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Cohen, P. Regulation and physiological roles of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase isoforms. Sci. STKE 2001, 2001, re17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firestone, G.L.; Giampaolo, J.R.; O’Keeffe, B.A. Stimulus-dependent regulation of serum and glucocorticoid inducible protein kinase (SGK) transcription, subcellular localization and enzymatic activity. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Deak, M.; Morrice, N.; Cohen, P. Characterization of the structure and regulation of two novel isoforms of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase. Biochem. J. 1999, 344 Pt 1, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestro, I.; Boya, P.; Martinez, A. Serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1, a new therapeutic target for autophagy modulation in chronic diseases. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2020, 24, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bago, R.; Malik, N.; Munson, M.J.; Prescott, A.R.; Davies, P.; Sommer, E.; Shpiro, N.; Ward, R.; Cross, D.; Ganley, I.G.; et al. Characterization of VPS34-IN1, a selective inhibitor of Vps34, reveals that the phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate-binding SGK3 protein kinase is a downstream target of class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem. J. 2014, 463, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, M.F.; Alvarez de la Rosa, D.; Alvarez, J.A.; Canessa, C.M. Multiple translational isoforms give functional specificity to serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 2072–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusz, A.M.; Brickley, D.R.; Pew, T.; Conzen, S.D. A novel N-terminal hydrophobic motif mediates constitutive degradation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase-1 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 2913–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belova, L.; Sharma, S.; Brickley, D.R.; Nicolarsen, J.R.; Patterson, C.; Conzen, S.D. Ubiquitin-proteasome degradation of serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase-1 (SGK-1) is mediated by the chaperone-dependent E3 ligase CHIP. Biochem. J. 2006, 400, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raikwar, N.S.; Snyder, P.M.; Thomas, C.P. An evolutionarily conserved N-terminal Sgk1 variant with enhanced stability and improved function. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2008, 295, F1440–F1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arteaga, M.F.; Coric, T.; Straub, C.; Canessa, C.M. A brain-specific SGK1 splice isoform regulates expression of ASIC1 in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 4459–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Fernandez, R.; Avila, J.; Arteaga, M.F.; Canessa, C.M.; Martin-Vasallo, P. The neuronal-specific SGK1.1 (SGK1_v2) kinase as a transcriptional modulator of BAG4, Brox, and PPP1CB genes expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 7462–7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulff, P.; Vallon, V.; Huang, D.Y.; Volkl, H.; Yu, F.; Richter, K.; Jansen, M.; Schlunz, M.; Klingel, K.; Loffing, J.; et al. Impaired renal Na(+) retention in the sgk1-knockout mouse. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 1263–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Y.; Wulff, P.; Volkl, H.; Loffing, J.; Richter, K.; Kuhl, D.; Lang, F.; Vallon, V. Impaired regulation of renal K+ elimination in the sgk1-knockout mouse. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandulache, D.; Grahammer, F.; Artunc, F.; Henke, G.; Hussain, A.; Nasir, O.; Mack, A.; Friedrich, B.; Vallon, V.; Wulff, P.; et al. Renal Ca2+ handling in sgk1 knockout mice. Pflug. Arch. 2006, 452, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Y.; Boini, K.M.; Friedrich, B.; Metzger, M.; Just, L.; Osswald, H.; Wulff, P.; Kuhl, D.; Vallon, V.; Lang, F. Blunted hypertensive effect of combined fructose and high-salt diet in gene-targeted mice lacking functional serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006, 290, R935–R944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Y.; Boini, K.M.; Osswald, H.; Friedrich, B.; Artunc, F.; Ullrich, S.; Rajamanickam, J.; Palmada, M.; Wulff, P.; Kuhl, D.; et al. Resistance of mice lacking the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1 against salt-sensitive hypertension induced by a high-fat diet. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2006, 291, F1264–F1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallon, V.; Huang, D.Y.; Grahammer, F.; Wyatt, A.W.; Osswald, H.; Wulff, P.; Kuhl, D.; Lang, F. SGK1 as a determinant of kidney function and salt intake in response to mineralocorticoid excess. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 289, R395–R401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahammer, F.; Henke, G.; Sandu, C.; Rexhepaj, R.; Hussain, A.; Friedrich, B.; Risler, T.; Metzger, M.; Just, L.; Skutella, T.; et al. Intestinal function of gene-targeted mice lacking serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2006, 290, G1114–G1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boini, K.M.; Hennige, A.M.; Huang, D.Y.; Friedrich, B.; Palmada, M.; Boehmer, C.; Grahammer, F.; Artunc, F.; Ullrich, S.; Avram, D.; et al. Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 mediates salt sensitivity of glucose tolerance. Diabetes 2006, 55, 2059–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, E.M.; Kraemer, B.F.; Borst, O.; Munzer, P.; Schonberger, T.; Schmidt, C.; Leibrock, C.; Towhid, S.T.; Seizer, P.; Kuhl, D.; et al. SGK1 sensitivity of platelet migration. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 30, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, J.A.; Feng, Y.; Dawson, K.; Behne, M.J.; Yu, B.; Wang, J.; Wyatt, A.W.; Henke, G.; Grahammer, F.; Mauro, T.M.; et al. Targeted disruption of the protein kinase SGK3/CISK impairs postnatal hair follicle development. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 4278–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, U.E.; Wolfer, D.P.; Grahammer, F.; Strutz-Seebohm, N.; Seebohm, G.; Lipp, H.P.; McCormick, J.A.; Hellweg, R.; Dawson, K.; Wang, J.; et al. Reduced locomotion in the serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase 3 knock out mouse. Behav. Brain Res. 2006, 167, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahammer, F.; Artunc, F.; Sandulache, D.; Rexhepaj, R.; Friedrich, B.; Risler, T.; McCormick, J.A.; Dawson, K.; Wang, J.; Pearce, D.; et al. Renal function of gene-targeted mice lacking both SGK1 and SGK3. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006, 290, R945–R950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnackenberg, C.; Costell, M.H.; Bernard, R.E.; Minuti, K.K.; Grygielko, E.T.; Parsons, M.J.; Laping, N.J.; Duddy, G. Compensatory role for Sgk2 mediated sodium reabsorption during salt deprivation in Sgk1 knockout mice. FASEB J. 2007, 21, A508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, M.A.; Pearson, R.B.; Hannan, R.D.; Sheppard, K.E. AKT-independent PI3-K signaling in cancer—Emerging role for SGK3. Cancer Manag. Res. 2013, 5, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, M.K.; Goya, L.; Ge, Y.; Maiyar, A.C.; Firestone, G.L. Characterization of sgk, a novel member of the serine/threonine protein kinase gene family which is transcriptionally induced by glucocorticoids and serum. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993, 13, 2031–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Wang, J.; Pearce, D. Regulation of epithelial ion transport by aldosterone through changes in gene expression. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2004, 217, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, H.; Nishida, E. The ERK MAP kinase pathway mediates induction of SGK (serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase) by growth factors. Genes Cells 2001, 6, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Li, J.; Sun, F.; Zhou, H.; Yang, J.; Yang, C. The functional duality of SGK1 in the regulation of hyperglycemia. Endocr. Connect. 2020, 9, R187–R194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, M.; Tapping, R.I.; Chao, T.H.; Lo, J.F.; King, C.C.; Yang, Y.; Lee, J.D. BMK1 mediates growth factor-induced cell proliferation through direct cellular activation of serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 8631–8634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Yamagiwa, Y.; Taffetani, S.; Han, J.; Patel, T. IL-6 activates serum and glucocorticoid kinase via p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2005, 289, C971–C981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Jang, Y.; You-Ten, A.I.; Okada, H.; Liepa, J.; Wakeham, A.; Zaugg, K.; Mak, T.W. p53-dependent inhibition of FKHRL1 in response to DNA damage through protein kinase SGK1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14057–14062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baban, B.; Liu, J.Y.; Mozaffari, M.S. SGK-1 regulates inflammation and cell death in the ischemic-reperfused heart: Pressure-related effects. Am. J. Hypertens. 2014, 27, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, R.; Menniti, M.; Agosti, V.; Boito, R.; Costa, N.; Bond, H.M.; Barbieri, V.; Tagliaferri, P.; Venuta, S.; Perrotti, N. IL-2 signals through Sgk1 and inhibits proliferation and apoptosis in kidney cancer cells. J. Mol. Med. 2007, 85, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, R.T.; Birnboim, H.C. Expression of serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase (sgk) mRNA is up-regulated by GM-CSF and other proinflammatory mediators in human granulocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000, 67, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Bhargava, A.; Mastroberardino, L.; Meijer, O.C.; Wang, J.; Buse, P.; Firestone, G.L.; Verrey, F.; Pearce, D. Epithelial sodium channel regulated by aldosterone-induced protein sgk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 2514–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldegger, S.; Klingel, K.; Barth, P.; Sauter, M.; Rfer, M.L.; Kandolf, R.; Lang, F. h-sgk serine-threonine protein kinase gene as transcriptional target of transforming growth factor beta in human intestine. Gastroenterology 1999, 116, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.S.; Sharma, S.C.; Falender, A.E.; Lo, Y.H. Expression of FKHR, FKHRL1, and AFX genes in the rodent ovary: Evidence for regulation by IGF-I, estrogen, and the gonadotropins. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002, 16, 580–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alliston, T.N.; Gonzalez-Robayna, I.J.; Buse, P.; Firestone, G.L.; Richards, J.S. Expression and localization of serum/glucocorticoid-induced kinase in the rat ovary: Relation to follicular growth and differentiation. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotti, N.; He, R.A.; Phillips, S.A.; Haft, C.R.; Taylor, S.I. Activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase (Sgk) by cyclic AMP and insulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 9406–9412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldegger, S.; Barth, P.; Raber, G.; Lang, F. Cloning and characterization of a putative human serine/threonine protein kinase transcriptionally modified during anisotonic and isotonic alterations of cell volume. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 4440–4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, M.L.; Maiyar, A.C.; Kim, B.; O’Keeffe, B.A.; Firestone, G.L. Expression of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible protein kinase, Sgk, is a cell survival response to multiple types of environmental stress stimuli in mammary epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 5871–5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imaizumi, K.; Tsuda, M.; Wanaka, A.; Tohyama, M.; Takagi, T. Differential expression of sgk mRNA, a member of the Ser/Thr protein kinase gene family, in rat brain after CNS injury. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1994, 26, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillon, S.; Klingel, K.; Warntges, S.; Sauter, M.; Gabrysch, S.; Pestel, S.; Tanneur, V.; Waldegger, S.; Zipfel, A.; Viebahn, R.; et al. Expression of the serine/threonine kinase hSGK1 in chronic viral hepatitis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2002, 12, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.M.; Leong, M.L.; Kim, B.; Wang, E.; Park, J.; Hemmings, B.A.; Firestone, G.L. Hyperosmotic stress stimulates promoter activity and regulates cellular utilization of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible protein kinase (Sgk) by a p38 MAPK-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 25262–25272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Klingel, K.; Wagner, C.A.; Stegen, C.; Warntges, S.; Friedrich, B.; Lanzendorfer, M.; Melzig, J.; Moschen, I.; Steuer, S.; et al. Deranged transcriptional regulation of cell-volume-sensitive kinase hSGK in diabetic nephropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 8157–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, M.F.; Wang, L.; Ravid, T.; Hochstrasser, M.; Canessa, C.M. An amphipathic helix targets serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 to the endoplasmic reticulum-associated ubiquitin-conjugation machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11178–11183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiemuth, D.; Lott, J.S.; Ly, K.; Ke, Y.; Teesdale-Spittle, P.; Snyder, P.M.; McDonald, F.J. Interaction of serum- and glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 (SGK1) with the WW-domains of Nedd4-2 is required for epithelial sodium channel regulation. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, C.; Sinha, I.; Garty, H. Characterization of the interactions between Nedd4-2, ENaC, and sgk-1 using surface plasmon resonance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2003, 1612, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickley, D.R.; Mikosz, C.A.; Hagan, C.R.; Conzen, S.D. Ubiquitin modification of serum and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase-1 (SGK-1). J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 43064–43070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Snyder, P.M. Nedd4-2 phosphorylation induces serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase (SGK) ubiquitination and degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 4518–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.; Wan, L.; Inuzuka, H.; Berg, A.H.; Tseng, A.; Zhai, B.; Shaik, S.; Bennett, E.; Tron, A.E.; Gasser, J.A.; et al. Rictor forms a complex with Cullin-1 to promote SGK1 ubiquitination and destruction. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.; Wan, L.; Wei, W. Phosphorylation of Rictor at Thr1135 impairs the Rictor/Cullin-1 complex to ubiquitinate SGK1. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, R.; Wang, J.; Melters, D.; Pearce, D. Glucocorticoid-induced Leucine zipper 1 stimulates the epithelial sodium channel by regulating serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 stability and subcellular localization. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 39905–39913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luginbuhl, J.; Sivaraman, D.M.; Shin, J.W. The essentiality of non-coding RNAs in cell reprogramming. Noncoding RNA Res. 2017, 2, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.L.; Tsai, Y.M.; Lien, C.T.; Kuo, P.L.; Hung, A.J. The Roles of MicroRNA in Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Fei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, C.; Li, F.R. Tissue microRNAs in non-small cell lung cancer detected with a new kind of liquid bead array detection system. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.; Shen, J.; Leng, Q.; Qin, M.; Zhan, M.; Jiang, F. MicroRNA-based biomarkers for diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Thorac. Cancer 2020, 11, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Zhan, Y.; Feng, J.; Luo, J.; Fan, S. MicroRNAs associated with therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Yang, G.; Xiong, G.; Cao, Z.; Zheng, S.; You, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y. miR-497 expression, function and clinical application in cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 55900–55911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.Y.; Wang, Y.; An, Z.J.; Shi, C.G.; Zhu, G.A.; Wang, B.; Lu, M.Y.; Pan, C.K.; Chen, P. Downregulation of miR-497 promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis by targeting HDGF in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 435, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Lu, J.; Wang, W.; Shi, C.; Han, B.; Yao, M. Role of miR-497 in VEGF-A-mediated cancer cell growth and invasion in non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 70, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Liu, B.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, C.; Jiang, Y. miR-497 and miR-34a retard lung cancer growth by co-inhibiting cyclin E1 (CCNE1). Oncotarget 2015, 6, 13149–13163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Sardo, F.; Strano, S.; Blandino, G. YAP and TAZ in Lung Cancer: Oncogenic Role and Clinical Targeting. Cancers 2018, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ma, R.; Yue, J.; Li, N.; Li, Z.; Qi, D. MiR-497 Suppresses YAP1 and Inhibits Tumor Growth in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 37, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ji, X.B.; Wang, L.H.; Qiu, J.G.; Zhou, F.M.; Liu, W.J.; Wan, D.D.; Lin, M.C.; Liu, L.Z.; Zhang, J.Y.; et al. Regulation of MicroRNA-497-Targeting AKT2 Influences Tumor Growth and Chemoresistance to Cisplatin in Lung Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, G.A.; Dumitru, C.D.; Shimizu, M.; Bichi, R.; Zupo, S.; Noch, E.; Aldler, H.; Rattan, S.; Keating, M.; Rai, K.; et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15524–15529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.R.; Li, H.J.; Li, T.T.; Zhao, Y.F.; Liu, Z.K.; Li, X.R. Prognostic Value of MicroRNA-15a in Human Cancers: A Meta-Analysis and Bioinformatics. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 2063823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandi, N.; Vassella, E. miR-34a and miR-15a/16 are co-regulated in non-small cell lung cancer and control cell cycle progression in a synergistic and Rb-dependent manner. Mol. Cancer 2011, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Hou, J.; Li, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Wei, J.; Song, D.; Hu, T.; Wu, Q.; Yang, J.Y.; Cai, J.C. miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p Negatively Regulate Twist1 to Repress Gastric Cancer Cell Invasion and Metastasis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 13, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, J.Y.; Yang, P.C. The EMT regulator slug and lung carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 2011, 32, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, S.; Güney, S.; Temiz, E.; Petrovic, N.; Gunes, S. Significance of miR-15a-5p and CNKSR3 as Novel Prognostic Biomarkers in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 1695–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xu, Z.; Ou, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J. The miR-15a/16 gene cluster in human cancer: A systematic review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 5496–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozok Çetintaş, V.; Tetik Vardarlı, A.; Düzgün, Z.; Tezcanlı Kaymaz, B.; Açıkgöz, E.; Aktuğ, H.; Kosova Can, B.; Gündüz, C.; Eroğlu, Z. miR-15a enhances the anticancer effects of cisplatin in the resistant non-small cell lung cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yin, B.; Yu, P.; Duan, X.; Liao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. SGK1 inhibition induces autophagy-dependent apoptosis via the mTOR-Foxo3a pathway. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 1139–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Yang, G.; Cao, Z.; Shen, K.; Zheng, L.; Xiao, J.; You, L.; Zhang, T. The prospect of serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 (SGK1) in cancer therapy: A rising star. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920940946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braicu, C.; Gulei, D.; Cojocneanu, R.; Raduly, L.; Jurj, A.; Knutsen, E.; Calin, G.A.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. miR-181a/b therapy in lung cancer: Reality or myth? Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y. Down-regulation of microRNA-181b is a potential prognostic marker of non-small cell lung cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2013, 209, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Ye, B.; Yang, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhao, H. MicroRNA-181 functions as a tumor suppressor in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by targeting Bcl-2. Tumour Biol. 2015, 36, 3381–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Meng, Q.; Jing, H.; Lu, H.; Yang, Y.; Cai, L.; Zhao, Y. MiR-181b regulates cisplatin chemosensitivity and metastasis by targeting TGFbetaR1/Smad signaling pathway in NSCLC. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Xie, F.; Gao, A.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Z.; Hu, Q.; Huang, W.; Huang, Q.; Lin, B.; et al. SOX2 regulates multiple malignant processes of breast cancer development through the SOX2/miR-181a-5p, miR-30e-5p/TUSC3 axis. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, D.; Li, P.; Wang, L.; Qiao, B.; Qin, X.; Li, L.; Wang, Y. MicroRNA-181a-5p Impedes IL-17-Induced Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer Proliferation and Migration through Targeting VCAM-1. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 42, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Fei, S.; Chen, D.; Cai, X.; Liu, L.; Lin, B.; Su, H.; Zhao, L.; et al. Evaluation of Tumor-Derived Exosomal miRNA as Potential Diagnostic Biomarkers for Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Using Next-Generation Sequencing. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5311–5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Zeng, X.; Zhao, L.; Wei, Q.; Yu, L.; Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Shan, F.; Wei, M. miR-181a Induces Macrophage Polarized to M2 Phenotype and Promotes M2 Macrophage-mediated Tumor Cell Metastasis by Targeting KLF6 and C/EBPalpha. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2016, 5, e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Du, J.; Zhu, G. SGK1 Mediates Hypoxic Pulmonary Hypertension through Promoting Macrophage Infiltration and Activation. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 2019, 2019, 3013765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Ma, S.; Dong, R.; Meng, W.; Ying, M.; Weng, Q.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Fang, Q.; et al. Tumor hypoxia enhances Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer metastasis by selectively promoting macrophage M2 polarization through the activation of ERK signaling. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 9664–9677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusai, K.; Wagner, B.; Roos, M.; Schmaderer, C.; Strobl, M.; Boini, K.M.; Grenz, A.; Kuhl, D.; Heemann, U.; Lang, F.; et al. The serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 in hypoxic renal injury. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 24, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matschke, J.; Wiebeck, E.; Hurst, S.; Rudner, J.; Jendrossek, V. Role of SGK1 for fatty acid uptake, cell survival and radioresistance of NCI-H460 lung cancer cells exposed to acute or chronic cycling severe hypoxia. Radiat. Oncol. 2016, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Chang, J.; Qiu, X.; Wang, E. Hsa-miR-125a-3p and hsa-miR-125a-5p are downregulated in non-small cell lung cancer and have inverse effects on invasion and migration of lung cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Sun, S.; Shi, J.; Cao, F.; Han, X.; Chen, Z. MicroRNA-125a-5p plays a role as a tumor suppressor in lung carcinoma cells by directly targeting STAT3. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidu, S.; Shi, L.; Magee, P.; Middleton, J.D.; Lagana, A.; Sahoo, S.; Leong, H.S.; Galvin, M.; Frese, K.; Dive, C.; et al. PDGFR-modulated miR-23b cluster and miR-125a-5p suppress lung tumorigenesis by targeting multiple components of KRAS and NF-kB pathways. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Huang, H.; Cui, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, Y. IFN-gamma promoted exosomes from mesenchymal stem cells to attenuate colitis via miR-125a and miR-125b. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, T.; Long, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. Identification and characterization of miR-96, a potential biomarker of NSCLC, through bioinformatic analysis. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Pu, X.; Wang, Q.; Cao, J.; Xu, F.; Xu, L.I.; Li, K. miR-96 induces cisplatin chemoresistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells by downregulating SAMD9. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhao, H.; Li, S. miR-96 promotes invasion and metastasis by targeting GPC3 in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 9081–9086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Hu, Y.; Ding, L.; Qi, P.; Wang, J.; Lu, S.; Li, Y. MiR-183-5p is required for non-small cell lung cancer progression by repressing PTEN. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, H.; Su, Y.; Kong, J.; Yu, H.; Qian, B. Up-regulation of microRNA-183-3p is a potent prognostic marker for lung adenocarcinoma of female non-smokers. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2014, 16, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Zhou, K.; Zha, Y.; Chen, D.; He, J.; Ma, H.; Liu, X.; Le, H.; Zhang, Y. Diagnostic Value of Serum miR-182, miR-183, miR-210, and miR-126 Levels in Patients with Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirono, T.; Jingushi, K.; Nagata, T.; Sato, M.; Minami, K.; Aoki, M.; Takeda, A.H.; Umehara, T.; Egawa, H.; Nakatsuji, Y.; et al. MicroRNA-130b functions as an oncomiRNA in non-small cell lung cancer by targeting tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Dong, J.; Li, S.; Xia, W.; Su, X.; Qin, X.; Chen, Y.; Ding, H.; Li, H.; Huang, A.; et al. An alternative microRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation of GADD45A by p53 in human non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Hu, L.; Li, X.; Geng, J.; Dai, M.; Bai, X. MicroRNA-130b promotes lung cancer progression via PPARgamma/VEGF-A/BCL-2-mediated suppression of apoptosis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zang, W.; Wang, H.; Chu, H.; Li, P.; Li, M.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, G. Downregulation of microRNA-182 inhibits cell growth and invasion by targeting programmed cell death 4 in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Tumour Biol. 2014, 35, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yu, L.; Dong, H.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y. MiR-182 enhances radioresistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells by regulating FOXO3. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2019, 46, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Liu, Y.H.; Wang, L.L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.H.; Qu, J.F.; Wang, S.F. MiR-182 promotes cell proliferation by suppressing FBXW7 and FBXW11 in non-small cell lung cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ren, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Chen, J. [Methylation Status of miR-182 Promoter in Lung Cancer Cell Lines]. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi 2015, 18, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, B.; Cui, F.; He, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, M. Hypoxia-induced microRNA-301b regulates apoptosis by targeting Bim in lung cancer. Cell Prolif. 2016, 49, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.K.; Zang, Q.L.; Li, G.X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.Z. Increased expression of microRNA-301a in nonsmall-cell lung cancer and its clinical significance. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2016, 12, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashita, Y.; Osada, H.; Tatematsu, Y.; Yamada, H.; Yanagisawa, K.; Tomida, S.; Yatabe, Y.; Kawahara, K.; Sekido, Y.; Takahashi, T. A polycistronic microRNA cluster, miR-17-92, is overexpressed in human lung cancers and enhances cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 9628–9632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Li, S. Detection of circulating exosomal miR-17-5p serves as a novel non-invasive diagnostic marker for non-small cell lung cancer patients. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Liu, X.; Han, L.; Shen, H.; Liu, L.; Shu, Y. Up-regulation of miR-9 expression as a poor prognostic biomarker in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2014, 16, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Wang, W.; Ding, W.; Zhang, L. MiR-9 is involved in TGF-beta1-induced lung cancer cell invasion and adhesion by targeting SOX7. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 2000–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.N.; Wang, Y.B.; Wang, W. TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer cells involves upregulation of miR-9 and downregulation of its target, E-cadherin. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2017, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, L.; Ma, Z.; Sun, G.; Luo, X.; Li, M.; Zhai, S.; Li, P.; Wang, X. Oncogenic miR-9 is a target of erlotinib in NSCLCs. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Lin, Q.; Qin, X.; Ruan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Lin, Z.; Su, Y.; Jian, Z. Serum and glucocorticoid kinase 1 promoted the growth and migration of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Gene 2016, 576, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbruzzese, C.; Mattarocci, S.; Pizzuti, L.; Mileo, A.M.; Visca, P.; Antoniani, B.; Alessandrini, G.; Facciolo, F.; Amato, R.; D’Antona, L.; et al. Determination of SGK1 mRNA in non-small cell lung cancer samples underlines high expression in squamous cell carcinomas. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 31, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Lv, W.; Li, Z.; Han, W. SGK1 protein expression is a prognostic factor of lung adenocarcinoma that regulates cell proliferation and survival. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019, 12, 391–408. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Shen, Q.; Xie, H.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, G.; Zhang, C.; Mohammed, A.; Wu, Y.; Ni, S.; Zhou, X. Serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1) is a predictor of poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer, and its dynamic pattern following treatment with SGK1 inhibitor and gamma-ray irradiation was elucidated. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 39, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, P.L. Warburg, me and Hexokinase 2: Multiple discoveries of key molecular events underlying one of cancers’ most common phenotypes, the “Warburg Effect”, i.e., elevated glycolysis in the presence of oxygen. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2007, 39, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennell, D.A.; Summers, Y.; Cadranel, J.; Benepal, T.; Christoph, D.C.; Lal, R.; Das, M.; Maxwell, F.; Visseren-Grul, C.; Ferry, D. Cisplatin in the modern era: The backbone of first-line chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 44, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.C.; Pennell, N.A. Early Use of Systemic Corticosteroids in Patients with Advanced NSCLC Treated with Nivolumab. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018, 13, 1771–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotow, J.; Bivona, T.G. Understanding and targeting resistance mechanisms in NSCLC. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Liu, K.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhou, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, T.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Cui, D.; et al. NDRG1 disruption alleviates cisplatin/sodium glycididazole-induced DNA damage response and apoptosis in ERCC1-defective lung cancer cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 100, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, F.; Nicassio, F.; Di Fiore, P.P. Unbiased vs. biased approaches to the identification of cancer signatures: The case of lung cancer. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, A.; Park, J.; Tran, H.; Hu, L.S.; Hemmings, B.A.; Greenberg, M.E. Protein kinase SGK mediates survival signals by phosphorylating the forkhead transcription factor FKHRL1 (FOXO3a). Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 952–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, T.; Wang, J.; Lin, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Levine, A.J.; Hu, W. Chronic restraint stress attenuates p53 function and promotes tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7013–7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasna, J.; Hague, F.; Rodat-Despoix, L.; Geerts, D.; Leroy, C.; Tulasne, D.; Ouadid-Ahidouch, H.; Kischel, P. Orai3 calcium channel and resistance to chemotherapy in breast cancer cells: The p53 connection. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jia, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; He, H.; Lin, Y.; Hu, L. Association of constitutive nuclear factor-kappaB activation with aggressive aspects and poor prognosis in cervical cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2009, 19, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karin, M.; Greten, F.R. NF-kappaB: Linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, D.; Guo, Z.; Gao, Z.; Deng, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.; Guo, C. Potential biomarkers involving IKK/RelA signal in early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Bai, L.; Liang, X.; Zhuang, J.; Lin, Y. Blockage of NF-kappaB by IKKbeta- or RelA-siRNA rather than the NF-kappaB super-suppressor IkappaBalpha mutant potentiates adriamycin-induced cytotoxicity in lung cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 105, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ju, W.; Renouard, J.; Aden, J.; Belinsky, S.A.; Lin, Y. 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin synergistically potentiates tumor necrosis factor-induced lung cancer cell death by blocking the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Lin, Y. Sensitization of TNF-induced cytotoxicity in lung cancer cells by concurrent suppression of the NF-kappaB and Akt pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 355, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, C.; Toi, M. Nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitors as sensitizers to anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.R.; Broad, R.M.; Comeau, L.D.; Parsons, S.J.; Mayo, M.W. Inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB chemosensitizes non-small cell lung cancer through cytochrome c release and caspase activation. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002, 123, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denlinger, C.E.; Rundall, B.K.; Jones, D.R. Modulation of antiapoptotic cell signaling pathways in non-small cell lung cancer: The role of NF-kappaB. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2004, 16, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.M.; Tergaonkar, V. NFkappaB signaling in carcinogenesis and as a potential molecular target for cancer therapy. Apoptosis 2009, 14, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, D.J.; Su, C.C.; Ma, Y.L.; Lee, E.H. SGK1 phosphorylation of IkappaB Kinase alpha and p300 Up-regulates NF-kappaB activity and increases N-Methyl-d-aspartate receptor NR2A and NR2B expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 4073–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karin, M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature 2006, 441, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitvogel, L.; Apetoh, L.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Kroemer, G. Immunological aspects of cancer chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nencioni, A.; Grunebach, F.; Patrone, F.; Ballestrero, A.; Brossart, P. Proteasome inhibitors: Antitumor effects and beyond. Leukemia 2007, 21, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera, C.; Hoya-Arias, R.; Haegeman, G.; Espinosa, L.; Bigas, A. Recruitment of IkappaBalpha to the hes1 promoter is associated with transcriptional repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 16537–16542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Bai, L.; Lin, Y. NF-kappaB in lung cancer, a carcinogenesis mediator and a prevention and therapy target. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2011, 16, 1172–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.H.; Pan, S.H.; Chang, W.H.; Hong, Q.S.; Chen, J.J.; Yu, S.L. PARVA promotes metastasis by modulating ILK signalling pathway in lung adenocarcinoma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhu, H.; Liao, Y.; Wu, W.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Wu, Y.; Sun, F.; Lin, H.W. Inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway reverses multi-drug resistance and EMT in Oct4(+)/Nanog(+) NSCLC cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 127, 110225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, J.; Jaromi, L.; Kvell, K.; Miskei, G.; Pongracz, J.E. WNT signaling—Lung cancer is no exception. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.Y.; Ng, C.S.H.; Yang, S.L.; Wang, S.; Zou, C.; Dong, Y.; Du, J.; Long, X.; et al. FOXP3 promotes tumor growth and metastasis by activating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and EMT in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; He, J.; Pan, Y.; Hao, F.; Xie, L.; Li, Q.; Qiu, X.; Wang, E. Inhibition of cytoplasmic GSK-3beta increases cisplatin resistance through activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in A549/DDP cells. Cancer Lett. 2013, 336, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Wang, J. beta-Catenin signaling pathway regulates cisplatin resistance in lung adenocarcinoma cells by upregulating Bcl-xl. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 2543–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, L.; Theodorescu, D. Determinants of Resistance to Checkpoint Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luke, J.J.; Bao, R.; Sweis, R.F.; Spranger, S.; Gajewski, T.F. WNT/β-catenin Pathway Activation Correlates with Immune Exclusion across Human Cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3074–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Shumilina, E. Regulation of ion channels by the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Ryu, P.D.; Lee, S.Y. Anti-proliferative effect of Kv1.3 blockers in A549 human lung adenocarcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 651, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gao, B.; Xiong, Q.J.; Wang, Y.C.; Huang, D.K.; Wu, W.N. Acid-sensing ion channels contribute to the effect of extracellular acidosis on proliferation and migration of A549 cells. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317705750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.H.; Dinudom, A.; Sanchez-Perez, A.; Kumar, S.; Cook, D.I. Akt mediates the effect of insulin on epithelial sodium channels by inhibiting Nedd4-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 29866–29873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.Y.; Zhong, L.X.; Feng, M.; Wang, J.F.; Liu, D.B.; Xiong, J.P. Over-expression of Orai1 mediates cell proliferation and associates with poor prognosis in human non-small cell lung carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 5080–5088. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, C.; Zeng, B.; Li, R.; Li, Z.; Fu, Q.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Dong, S.; Lai, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Knockdown of STIM1 expression inhibits non-small-cell lung cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in nude mouse xenografts. Bioengineered 2019, 10, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Xu, L.; Lin, D.; Cai, S.; Zou, F. The apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer induced by cisplatin through modulation of STIM1. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2013, 65, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualdani, R.; de Clippele, M.; Ratbi, I.; Gailly, P.; Tajeddine, N. Store-Operated Calcium Entry Contributes to Cisplatin-Induced Cell Death in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Cancers 2019, 11, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Liu, S.; Gallolu Kankanamalage, S.; Borromeo, M.D.; Girard, L.; Gazdar, A.F.; Minna, J.D.; Johnson, J.E.; Cobb, M.H. The Epithelial Sodium Channel (alphaENaC) Is a Downstream Therapeutic Target of ASCL1 in Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Tumors. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 11, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Manochakian, R.; James, L.; Azzouqa, A.G.; Shi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, K.; Lou, Y. Emerging therapeutic agents for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, C.; Dattilo, V.; D’Antona, L.; Menniti, M.; Bianco, C.; Ortuso, F.; Alcaro, S.; Schenone, S.; Perrotti, N.; Amato, R. SGK1, the New Player in the Game of Resistance: Chemo-Radio Molecular Target and Strategy for Inhibition. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 39, 1863–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Zhang, Z.H.; Wu, P.; Li, L.; Huang, J.M. Preliminary study of apoptotic inhibition and its molecular mechanism of dexamethasone on cisplatin-induced human lung adenocarcinoma cell line SPCA/I. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2013, 44, 902–906. [Google Scholar]

- Melotte, V.; Qu, X.; Ongenaert, M.; van Criekinge, W.; de Bruine, A.P.; Baldwin, H.S.; van Engeland, M. The N-myc downstream regulated gene (NDRG) family: Diverse functions, multiple applications. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 4153–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, M.; Blaes, J.; Pusch, S.; Sahm, F.; Czabanka, M.; Luger, S.; Bunse, L.; Solecki, G.; Eichwald, V.; Jugold, M.; et al. mTOR target NDRG1 confers MGMT-dependent resistance to alkylating chemotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, V.; Suo, C.; Orear, C.; van den Oord, J.; Balogh, Z.; Guegan, J.; Job, B.; Meurice, G.; Ripoche, H.; Calza, S.; et al. Integrated molecular portrait of non-small cell lung cancers. BMC Med. Genom. 2013, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, E. Increased NDRG1 expression is associated with advanced T stages and poor vascularization in non-small cell lung cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. POR 2012, 18, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Kawahara, A.; Hattori, S.; Taira, T.; Tsurutani, J.; Watari, K.; Shibata, T.; Murakami, Y.; Takamori, S.; Ono, M.; et al. NDRG1/Cap43/Drg-1 may predict tumor angiogenesis and poor outcome in patients with lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2012, 7, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Q.; Jiao, X.; Kuang, F.; Hou, B.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, W.; Sun, G.; Ba, Y.; Yu, D.; Wang, D.; et al. FoxO3a inhibiting expression of EPS8 to prevent progression of NSCLC: A new negative loop of EGFR signaling. EBioMedicine 2019, 40, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Guo, N.; Zhang, N.; Miao, Z.; Guo, X.; Peng, N.; Zhang, R.; Miao, Y. Association of ZEB1 and FOXO3a protein with invasion/metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2017, 10, 11308–11316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mikse, O.R.; Blake, D.C., Jr.; Jones, N.R.; Sun, Y.W.; Amin, S.; Gallagher, C.J.; Lazarus, P.; Weisz, J.; Herzog, C.R. FOXO3 encodes a carcinogen-activated transcription factor frequently deleted in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 6205–6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reppert, S.; Boross, I.; Koslowski, M.; Tureci, O.; Koch, S.; Lehr, H.A.; Finotto, S. A role for T-bet-mediated tumour immune surveillance in anti-IL-17A treatment of lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenbaugh, A.; Sharma, S.; Dubinett, S.M.; Wei, S.H.; Aranda, R.; Cheroutre, H.; Fowell, D.J.; Binder, S.; Tsao, B.; Locksley, R.M.; et al. Altered immune responses in interleukin 10 transgenic mice. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 2101–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.J.; Levy, D.E.; Johnstone, R.W.; Clarke, C.J. IFNgamma signaling-does it mean JAK-STAT? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008, 19, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hage, F.; Vergnon, I.; Grunenwald, D.; Soria, J.C.; Chouaib, S.; Mami-Chouaib, F. Generation of diverse mutated tumor antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in a lung cancer patient with long survival. Oncol. Rep. 2005, 14, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dennis, K.L.; Blatner, N.R.; Gounari, F.; Khazaie, K. Current status of interleukin-10 and regulatory T-cells in cancer. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2013, 25, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geginat, J.; Larghi, P.; Paroni, M.; Nizzoli, G.; Penatti, A.; Pagani, M.; Gagliani, N.; Meroni, P.; Abrignani, S.; Flavell, R.A. The light and the dark sides of Interleukin-10 in immune-mediated diseases and cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016, 30, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherwinski, H.M.; Schumacher, J.H.; Brown, K.D.; Mosmann, T.R. Two types of mouse helper T cell clone. III. Further differences in lymphokine synthesis between Th1 and Th2 clones revealed by RNA hybridization, functionally monospecific bioassays, and monoclonal antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 1987, 166, 1229–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, R.M.; Rutitzky, L.I.; Urban, J.F., Jr.; Stadecker, M.J.; Gause, W.C. Protective immune mechanisms in helminth infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neurath, M.F.; Finotto, S. The emerging role of T cell cytokines in non-small cell lung cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2012, 23, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannarile, L.; Fallarino, F.; Agostini, M.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Mazzon, E.; Vacca, C.; Genovese, T.; Migliorati, G.; Ayroldi, E.; Riccardi, C. Increased GILZ expression in transgenic mice up-regulates Th-2 lymphokines. Blood 2006, 107, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Duan, M.C.; Han, W.; Jin, P.W.; Wei, Y.P.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, L.M.; Li, J.C. Disturbed Th17/Treg Balance in Patients with Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Inflammation 2015, 38, 2156–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, A.P.; Johansson, M.; Ruffell, B.; Yagui-Beltran, A.; Lau, J.; Jablons, D.M.; Coussens, L.M. Tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells inhibit endogenous cytotoxic T cell responses to lung adenocarcinoma. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, Z.Y.; Sun, B.; Wang, G.Y.; Fu, Z.; Liu, Y.M.; Kong, Q.F.; Wang, J.H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.Y.; et al. Effects of IL-17A on the occurrence of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 12, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, C.; Yosef, N.; Thalhamer, T.; Zhu, C.; Xiao, S.; Kishi, Y.; Regev, A.; Kuchroo, V.K. Induction of pathogenic TH17 cells by inducible salt-sensing kinase SGK1. Nature 2013, 496, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Ghilardi, N.; Xie, M.H.; de Sauvage, F.J.; Gurney, A.L. Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 1910–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, S.; Thalhamer, T.; Madi, A.; Han, T.; Kuchroo, V. SGK1 Governs the Reciprocal Development of Th17 and Regulatory T Cells. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, E.M.; Williams, C.B. The T(reg)/Th17 cell balance: A new paradigm for autoimmunity. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 65, 26R–31R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, E.A.; Ng, K.W.; Kung, S.H.; Conway, E.M.; Martinez, V.D.; Halvorsen, E.C.; Rowbotham, D.A.; Vucic, E.A.; Plumb, A.W.; Becker-Santos, D.D.; et al. Emerging roles of T helper 17 and regulatory T cells in lung cancer progression and metastasis. Mol. Cancer 2016, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knochelmann, H.M.; Dwyer, C.J.; Bailey, S.R.; Amaya, S.M.; Elston, D.M.; Mazza-McCrann, J.M.; Paulos, C.M. When worlds collide: Th17 and Treg cells in cancer and autoimmunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 15, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, M.C.; Zhong, X.N.; Liu, G.N.; Wei, J.R. The Treg/Th17 paradigm in lung cancer. J. Immunol. Res. 2014, 2014, 730380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherk, A.B.; Frigo, D.E.; Schnackenberg, C.G.; Bray, J.D.; Laping, N.J.; Trizna, W.; Hammond, M.; Patterson, J.R.; Thompson, S.K.; Kazmin, D.; et al. Development of a small-molecule serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase-1 antagonist and its evaluation as a prostate cancer therapeutic. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 7475–7483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, J.; Meyer, T.; Wade, W.; Lingardo, L.; Batova, A.; Alton, G.; Pallai, P. Drug-like inhibitors of SGK1: Discovery and optimization of low molecular weight fragment leads. In Proceedings of the AACR 107th Annual Meeting 2016, New Orleans, LA, USA, 16–20 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mansley, M.K.; Wilson, S.M. Effects of nominally selective inhibitors of the kinases PI3K, SGK1 and PKB on the insulin-dependent control of epithelial Na+ absorption. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 161, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, T.F.; Boini, K.M.; Beier, N.; Scholz, W.; Fuchss, T.; Lang, F. EMD638683, a novel SGK inhibitor with antihypertensive potency. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 28, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuso, F.; Amato, R.; Artese, A.; D’Antona, L.; Costa, G.; Talarico, C.; Gigliotti, F.; Bianco, C.; Trapasso, F.; Schenone, S.; et al. In silico identification and biological evaluation of novel selective serum/glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 inhibitors based on the pyrazolo-pyrimidine scaffold. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 1828–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halland, N.; Schmidt, F.; Weiss, T.; Saas, J.; Li, Z.; Czech, J.; Dreyer, M.; Hofmeister, A.; Mertsch, K.; Dietz, U.; et al. Discovery of N-[4-(1H-Pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazin-6-yl)-phenyl]-sulfonamides as Highly Active and Selective SGK1 Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toska, E.; Castel, P.; Chhangawala, S.; Arruabarrena-Aristorena, A.; Chan, C.; Hristidis, V.C.; Cocco, E.; Sallaku, M.; Xu, G.; Park, J.; et al. PI3K Inhibition Activates SGK1 via a Feedback Loop to Promote Chromatin-Based Regulation of ER-Dependent Gene Expression. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 294–306.e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Lan, C.; Zhou, J.; Fu, W.; Long, X.; An, Y.; Jiao, G.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; et al. Development of a new analog of SGK1 inhibitor and its evaluation as a therapeutic molecule of colorectal cancer. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 2256–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezzerides, V.J.; Zhang, A.; Xiao, L.; Simonson, B.; Khedkar, S.A.; Baba, S.; Ottaviano, F.; Lynch, S.; Hessler, K.; Rigby, A.C.; et al. Inhibition of serum and glucocorticoid regulated kinase-1 as novel therapy for cardiac arrhythmia disorders. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Stimuli | Regulators of SGK1 | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | IL-2 | [78] |

| IL-6 | [75] | |

| Colony-Stimulating Factor 2 | [79] | |

| TNF-α | [79] | |

| Growth Factors | Glucocorticoids | [70] |

| Mineralocorticoids | [80] | |

| FGF | [72] | |

| Serum | [70] | |

| TGF-β | [81] | |

| PDGF | [72] | |

| FSH | [82] | |

| LH | [83] | |

| Insulin | [84] | |

| IGF1 | [26] | |

| Cellular stress | Osmotic stress | [85] |

| Heat-shock | [86] | |

| UV | [86] | |

| Ischemic injury | [87] | |

| Hepatitis | [88] | |

| Sorbitol | [89] | |

| Hydrogen peroxide | [47] | |

| Neuronal injury | [87] | |

| High Glucose | [90] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guerriero, I.; Monaco, G.; Coppola, V.; Orlacchio, A. Serum and Glucocorticoid-Inducible Kinase 1 (SGK1) in NSCLC Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13110413

Guerriero I, Monaco G, Coppola V, Orlacchio A. Serum and Glucocorticoid-Inducible Kinase 1 (SGK1) in NSCLC Therapy. Pharmaceuticals. 2020; 13(11):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13110413

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuerriero, Ilaria, Gianni Monaco, Vincenzo Coppola, and Arturo Orlacchio. 2020. "Serum and Glucocorticoid-Inducible Kinase 1 (SGK1) in NSCLC Therapy" Pharmaceuticals 13, no. 11: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13110413

APA StyleGuerriero, I., Monaco, G., Coppola, V., & Orlacchio, A. (2020). Serum and Glucocorticoid-Inducible Kinase 1 (SGK1) in NSCLC Therapy. Pharmaceuticals, 13(11), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13110413