In Situ Oil–Gas Separator Enabled Carrier-Free Photoacoustic Sensing of Acetylene

Highlights

- A real-time photoacoustic spectroscopy system, integrated with a custom-designed multilayer oil–gas separation membrane, was developed for sensitive acetylene detection in transformer oil.

- The proposed system demonstrates a rapid response and high accuracy in continuous, in situ monitoring of dissolved gases, outperforming conventional off-line methods.

- The new approach enables timely transformer fault diagnosis, enhancing the reliability and safety of power equipment.

- This work lays a foundation for future development of compact and efficient online dissolved gas analysis (DGA) solutions for industrial applications.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Design of the Proposed PAS System

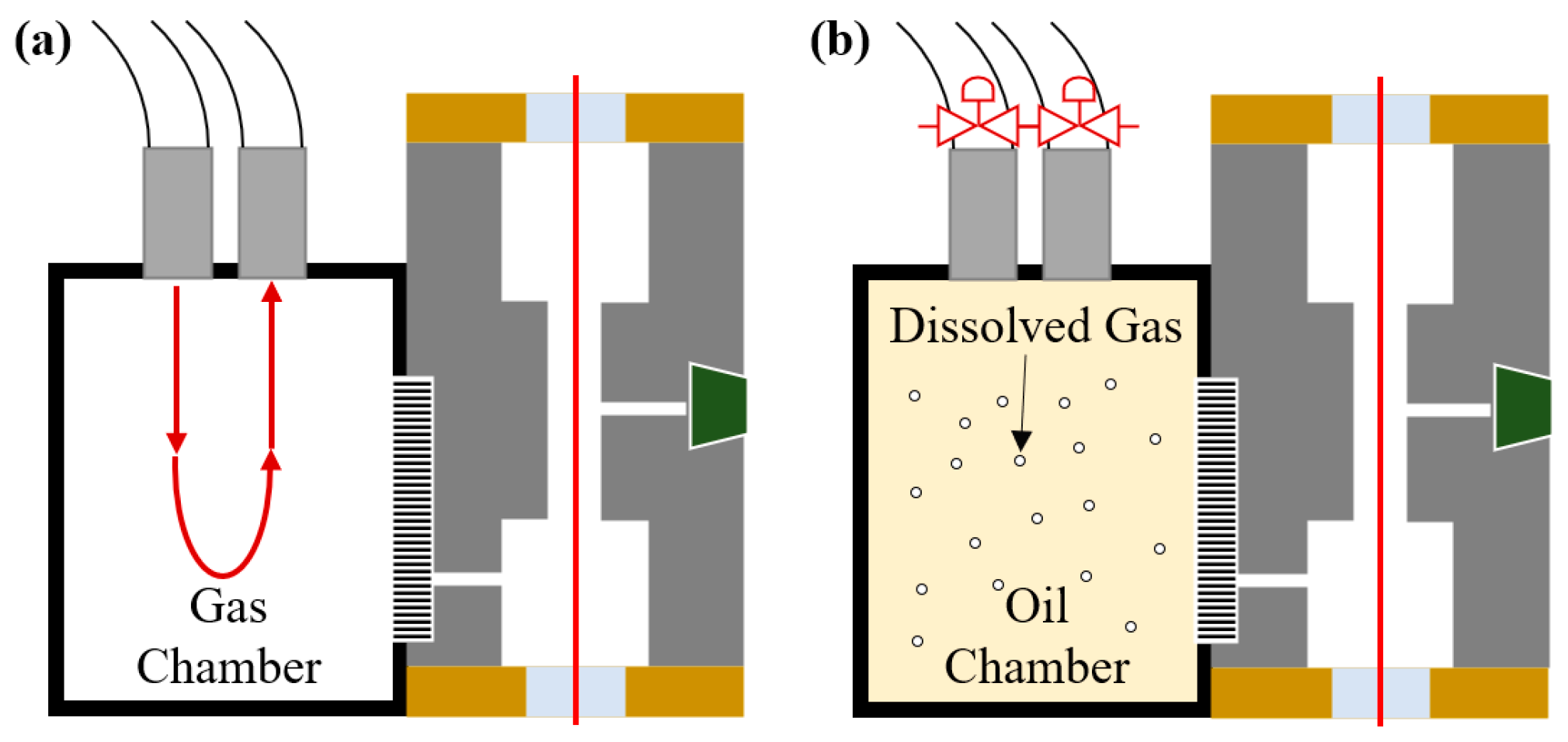

2.1. Concept of the System

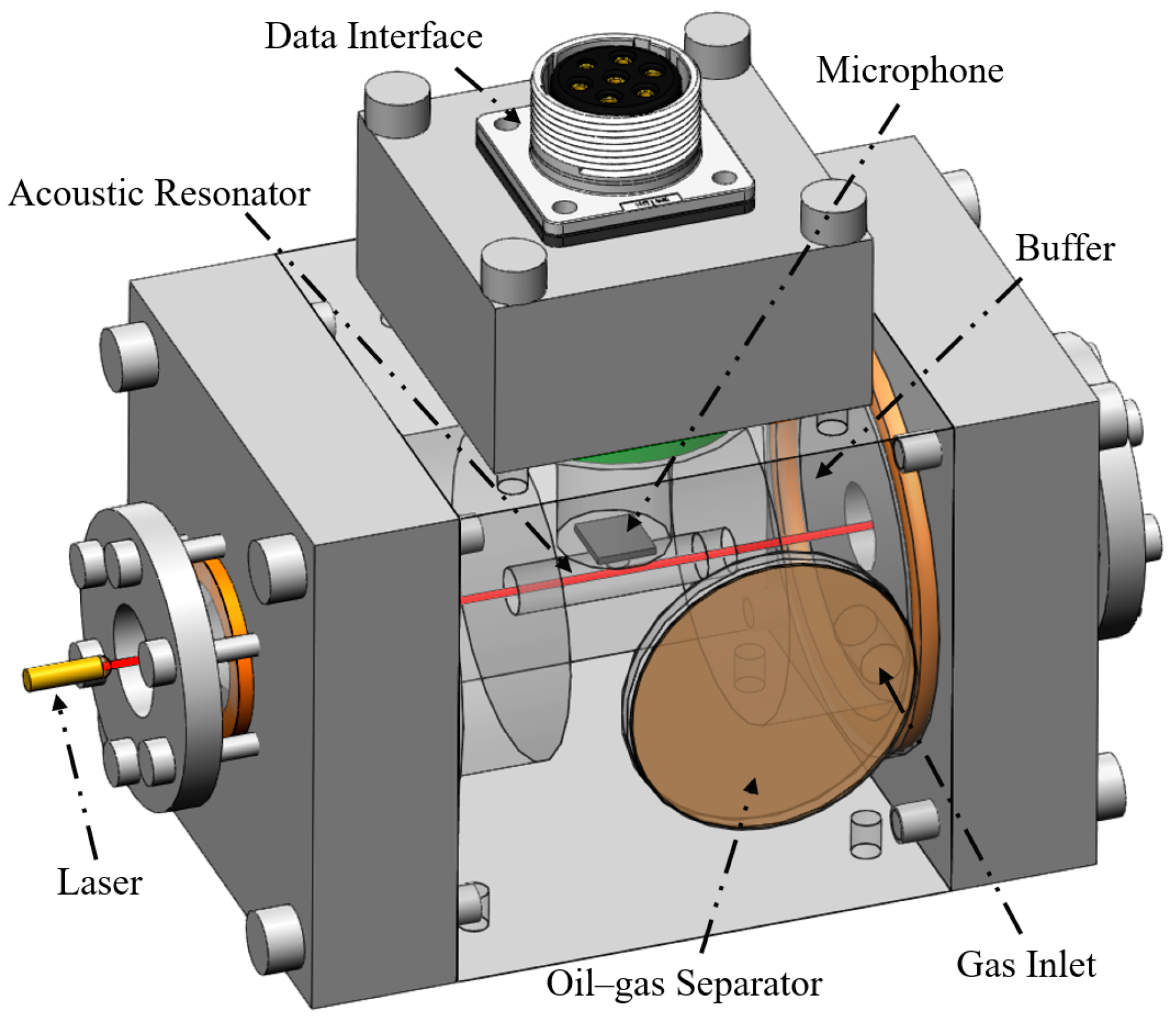

2.2. Modeling and Design of the PAS Cell

2.3. Design of the Oil–Gas Separator

3. Fabrication and Implementation

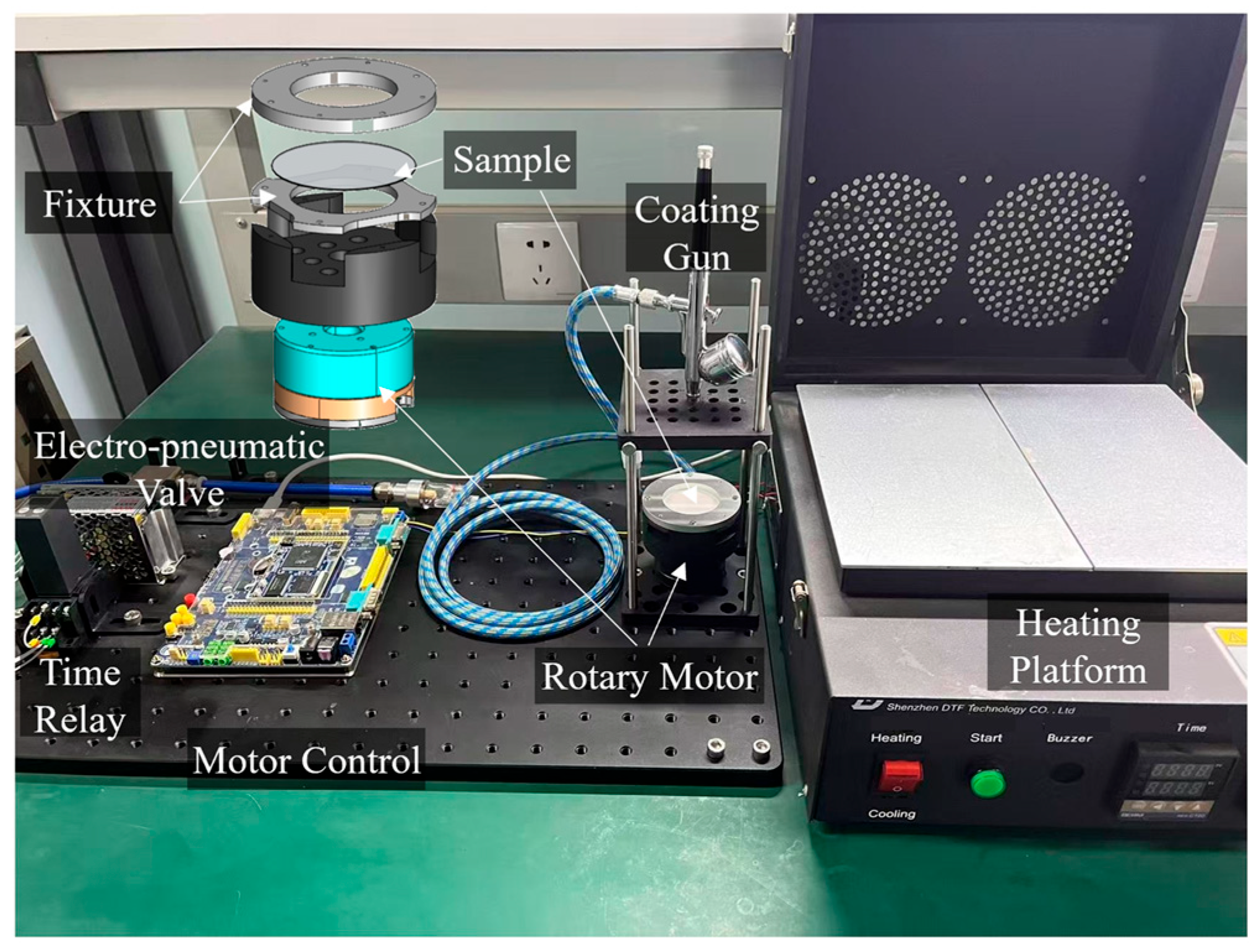

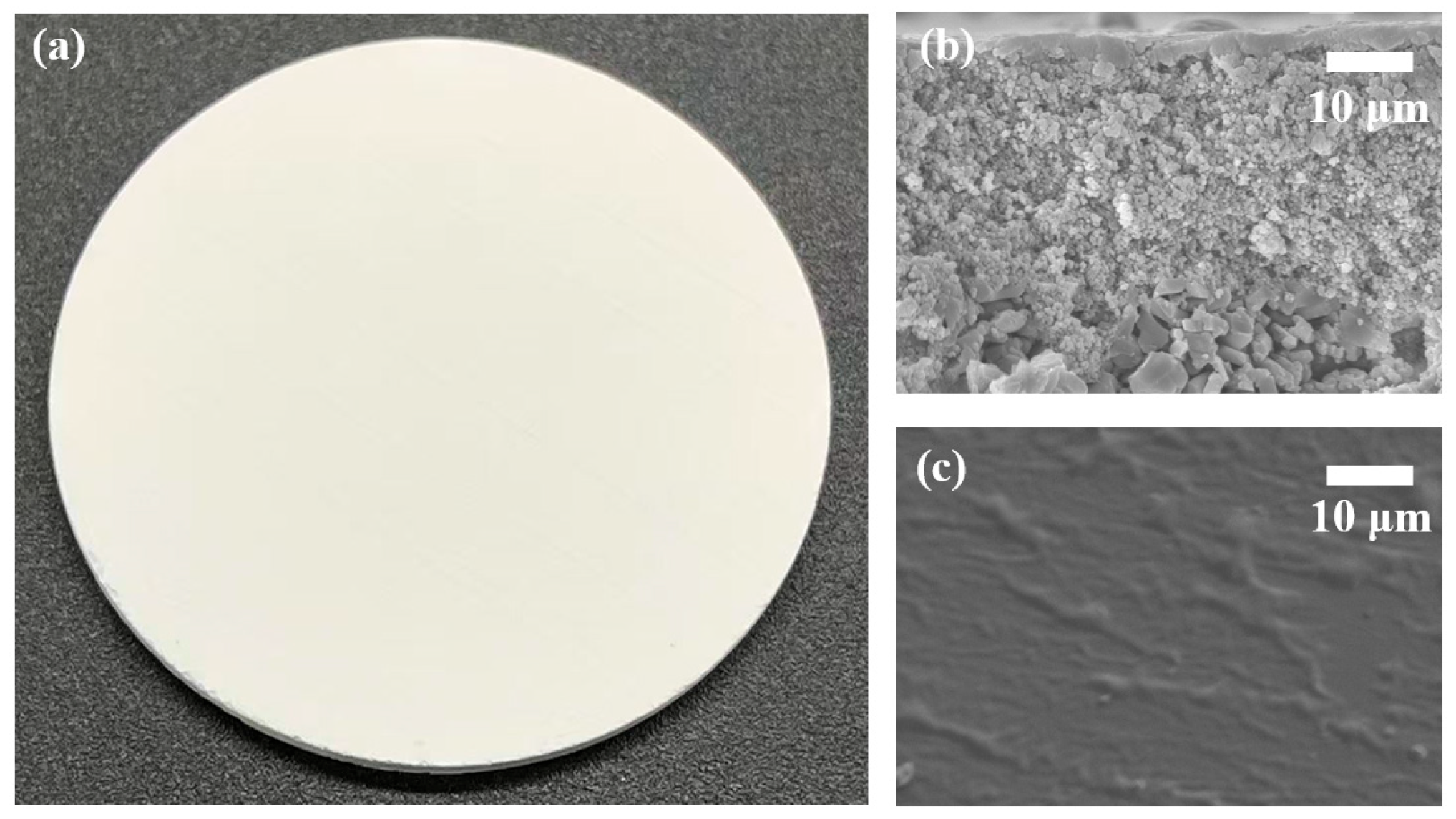

3.1. Fabrication of the Separator

3.2. Implementation of the PAS System

4. Results

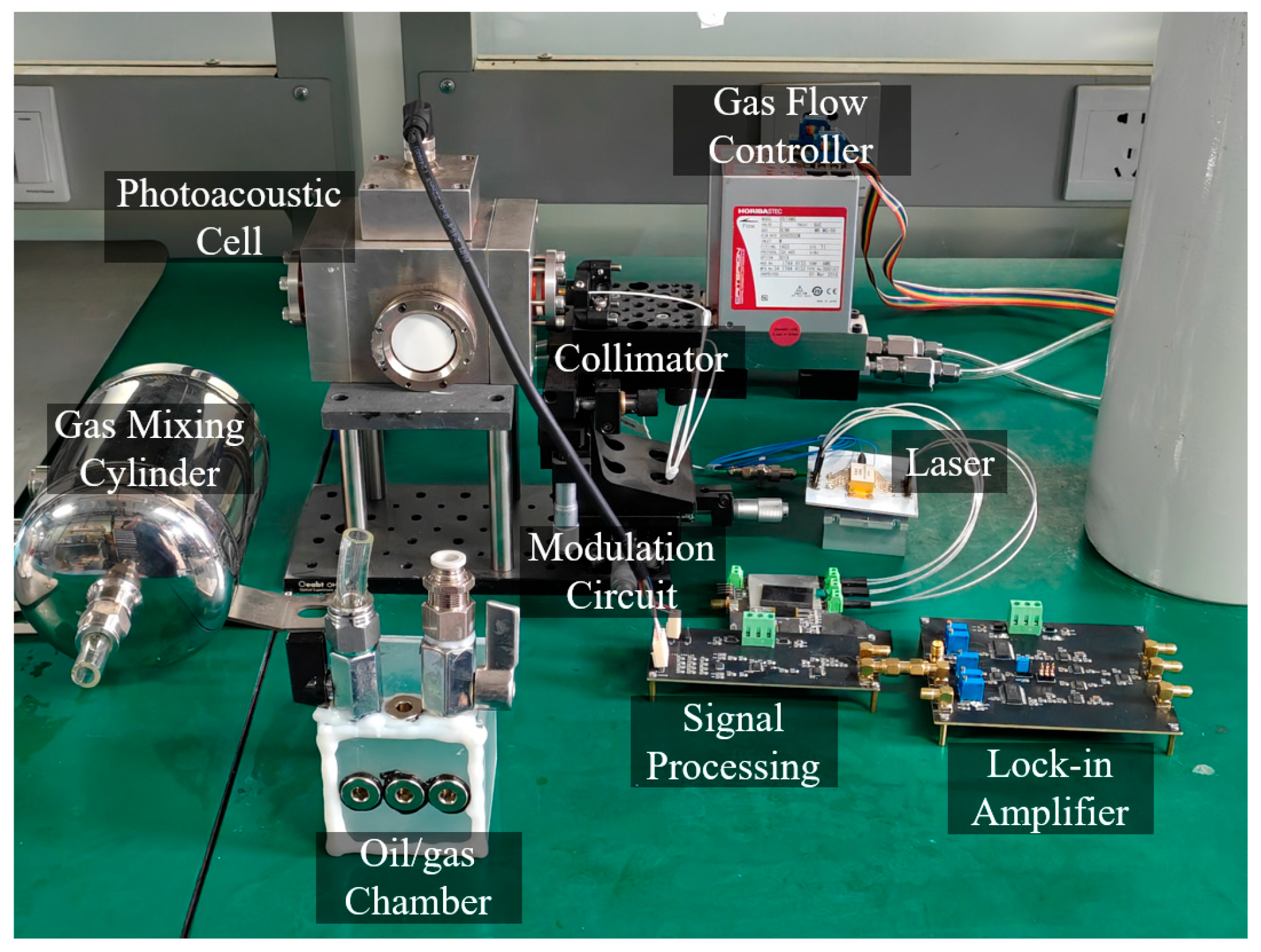

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Eigenfrequency of the PAS Cell

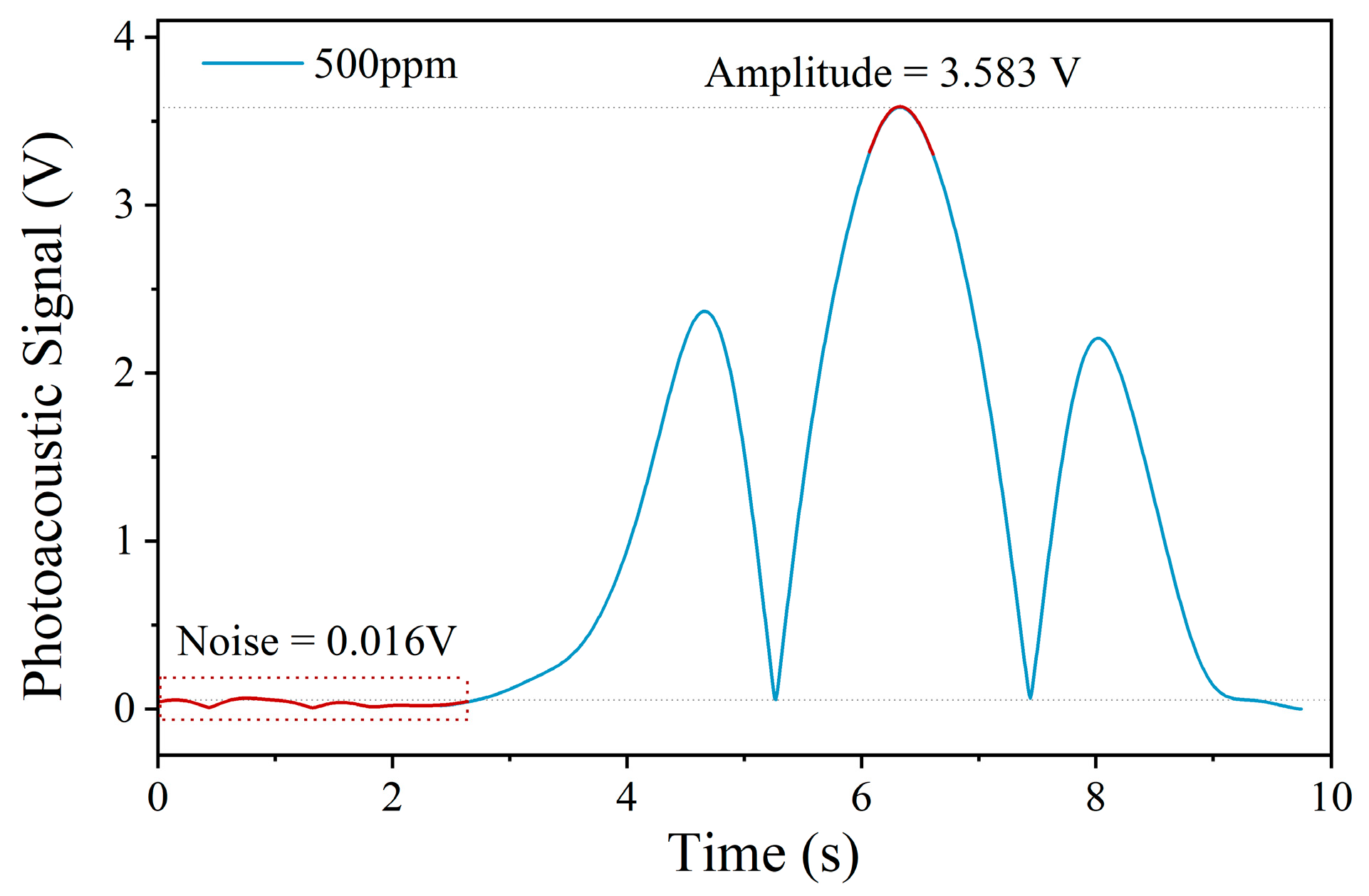

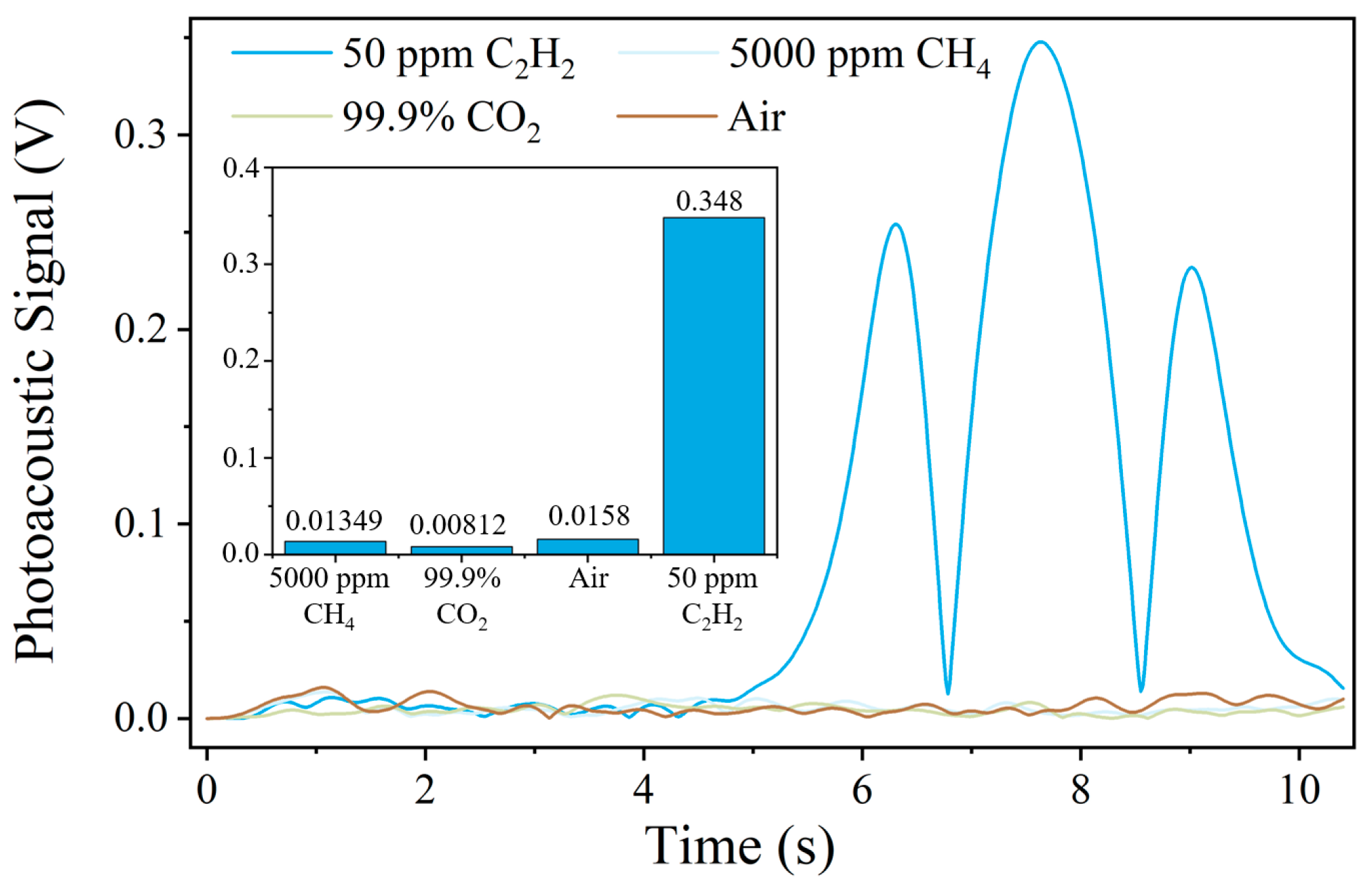

4.3. Sensitivity of the PAS System

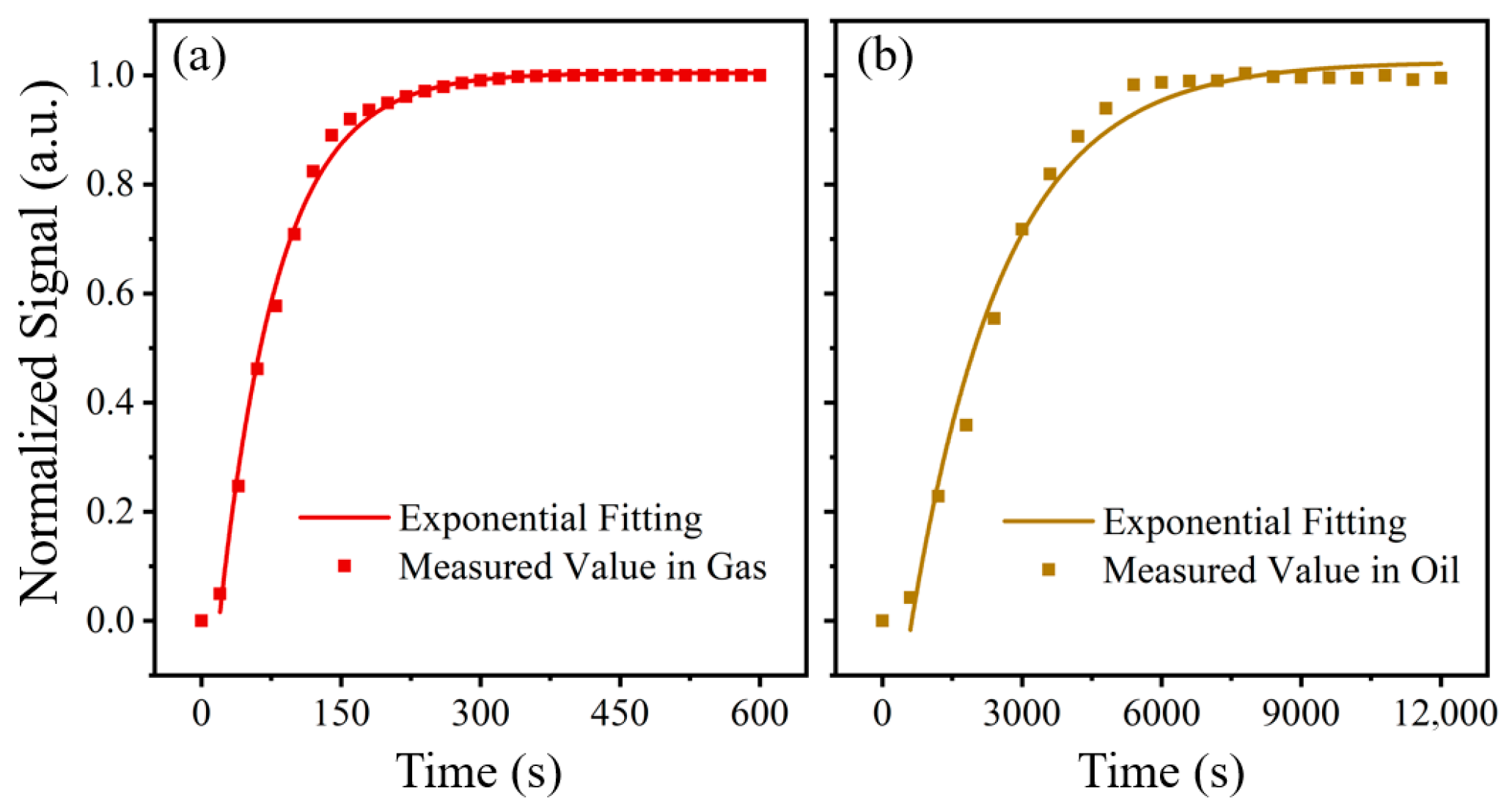

4.4. Response Time of the System

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DGA | Dissolved gas analysis |

| PAS | Photoacoustic spectroscopy |

| DDS | Direct digital synthesis |

| NTC | Negative temperature coefficient |

| FWHM | Full width at half maxima |

References

- Rojas, F.; Jerez, C.; Hackl, C.M.; Kalmbach, O.; Pereda, J.; Lillo, J. Faults in modular multilevel cascade converters—Part II: Fault tolerance, fault detection and diagnosis, and system reconfiguration. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2022, 3, 594–614. [Google Scholar]

- Hrishikesan, V.; Kumar, C. Operation of meshed hybrid microgrid during adverse grid conditions with storage integrated smart transformer. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2021, 2, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, F.F.; Hassan, M.A.; Azmy, A.M.; Atiya, E.G. Graphical shape in Cartesian plane based on dissolved gas analysis for power transformer incipient faults discrimination. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2024, 32, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Littler, T.; Liu, X. Gaussian process multi-class classification for transformer fault diagnosis using dissolved gas analysis. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2021, 28, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Li, X.; Feng, Y.; Yang, H.; Lv, W. Investigation on micro-mechanism of palm oil as natural ester insulating oil for overheating thermal fault analysis of transformers. High Volt. 2022, 7, 812–824. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Fei, R.; Shang, J. Effect of aging degree on partial discharge degradation of oil-paper insulation. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2022, 28, 2099–2107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Du, L.; Jiang, T.; Cai, N.; Song, R.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Experimental study on the transition process from partial discharge to arc discharge of oil–paper insulation based on fibre-optic sensors. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2023, 17, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, F.; Sun, Q.; Bin, F.; Ding, J.; Ye, H. SOFC detector for portable gas chromatography: High-sensitivity detection of dissolved gases in transformer oil. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2017, 24, 2854–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Mu, H.; Zhang, G.; Lin, H.; Shao, X. A Review of Gas Generation Mechanisms and Optical Detection Techniques for Mineral Oil. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2024, 31, 2874–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Gu, F.; Dai, W.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J. Research on NDIR three-component gas sensor and its compensation technology. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 186, 108835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Qi, H.; Zhao, X.; Guo, M.; An, R.; Chen, K. Multi-pass absorption enhanced photoacoustic spectrometer based on combined light sources for dissolved gas analysis in oil. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2022, 159, 107221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Cui, F.; Wang, A. A comparative study on the detection of transformer insulating oil by photoacoustic spectroscopy and gas chromatography. In Proceedings of the The 3rd International Conference on Optoelectronic Information and Functional Materials (OIFM 2024), Wuhan, China, 19–21 April 2024; pp. 392–396. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Hu, M.; Yao, L.; Xu, Z.; Deng, H.; Kan, R. Frequency-domain detection for frequency-division multiplexing QEPAS. Sensors 2022, 22, 4030. [Google Scholar]

- Fathy, A.; Sabry, Y.M.; Hunter, I.W.; Khalil, D.; Bourouina, T. Direct absorption and photoacoustic spectroscopy for gas sensing and analysis: A critical review. Laser Photonics Rev. 2022, 16, 2100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, K.; Zhao, J.; Qi, H.; Zhao, X.; Ma, F.; Han, X.; Guo, M.; An, R. High-sensitivity dynamic analysis of dissolved gas in oil based on differential photoacoustic cell. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 161, 107394. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; An, R.; Li, C.; Kang, Y.; Ma, F.; Zhao, X.; Guo, M.; Qi, H.; Zhao, J. Detection of ultra-low concentration acetylene gas dissolved in oil based on fiber-optic photoacoustic sensing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 154, 108299. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Huang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Luo, W.; Hu, Q.; Xiao, C. Study on a novel PTFE membrane with regular geometric pore structures fabricated by near-field electrospinning, and its applications. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 603, 118014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, X.; Feng, J.; Chang, Y.; Cao, F. Design and optimization of a novel porous plate oil–gas separator. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; He, Z.; Liu, S.; Huang, J. Research on New Oil-Gas Separation Technology for Transformerse. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Energy, Power and Electrical Engineering (EPEE), Wuhan, China, 15–17 September 2023; pp. 410–415. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, T.; Sun, H.; Long, Y.; Chen, W.; Wan, F. In-situ Raman Spectroscopy Detection of Dissolved Gases in Transformer Oil Based on Oil-gas Separation Membrane. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC), Chongqing, China, 28–30 November 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Ye, X.; Wang, H.; Yin, S.; Chen, G.; Huang, B.; Yang, P.; Wang, F. A New Gas Logging Method Based on Semipermeable Film Degasser and Infrared Spectrum. Petrophys.-SPWLA J. Form. Eval. Reserv. Descr. 2024, 65, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, C.; Zhu, M.; Chen, K. Miniature mid-infrared photoacoustic gas sensor for detecting dissolved carbon dioxide in seawater. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 405, 135370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Guo, M.; Yang, B.; Jin, F.; Wang, G.; Ma, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, B.; Deng, H.; Gong, Z. Highly sensitive optical fiber photoacoustic sensor for in situ detection of dissolved gas in oil. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yoon, H.W.; Paul, D.R.; Freeman, B.D. Gas transport properties of PDMS-coated reverse osmosis membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 604, 118009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabarov, S.; Huseynov, R.; Ayyubova, G.S.; Trukhanov, S.; Trukhanov, A.; Aliyev, Y.; Thabethe, T.T.; Mauyey, B.; Kuterbekov, K.; Kaminski, G. Evaluation of structural characteristics BaFe (12-x) InxO19 hexaferrite compounds at high temperatures. Solid State Commun. 2024, 386, 115529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabarov, S.; Nabiyeva, A.K.; Samadov, S.; Abiyev, A.; Sidorin, A.; Trung, N.; Orlov, O.; Mauyey, B.; Trukhanov, S.; Trukhanov, A. Study defects formation mechanism in La1-xBaxMnO3 perovskite manganite by positron annihilation lifetime and Doppler broadening spectroscopy. Solid State Ion. 2024, 414, 116640. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Li, K.; Liao, Z.; Xie, X.; Zhang, G. Influence of oil status on membrane-based gas–oil separation in DGA. Sensors 2022, 22, 3629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.-C.; Chen, C.; Lin, J.Y. Teflon AF2400 hollow fiber membrane contactor for dissolved gas-in-oil extraction: Mass transfer characteristics. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 16795–16804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Hua, M.; He, Y.; Zhu, P.; Lu, H.; Li, Y. Sensitivity Enhancement of a Miniaturized Non-resonant Photoacoustic Spectroscopy CO2 Sensor. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Hussam, A.; Weber, S.-G. Properties and transport behavior of perfluorotripentylamine (FC-70)-doped amorphous teflon AF2400 films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 17867–17879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansena, J.-C.; Friessb, K.; Drioli, E. Organic vapour transport in glassy perfluoropolymer membranes: A simple semi-quantitative approach to analyze clustering phenomena by time lag measurements. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 367, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ma, F.; Sun, C.; Qi, H.; Han, X.; Guo, M.; Chen, K. In-situ detection of dissolved C2H2/CH4 with frequency-division-multiplexed fiber-optic photoacoustic sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 435, 137651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, Q.; Jin, Y.; Meng, Y.; Shen, L.; Zhu, X.; Gao, H.; Chen, C. Novel omniphobic Teflon/PAI composite membrane prepared by vacuum-assisted dip-coating strategy for dissolved gases separation from transformer oil. Coatings 2025, 15, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Thickness | Separator Material | Diffusion Mode | Response Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [20] | N/A | Teflon AF2400 membrane | Without oil pump | 720 min |

| [23] | 12.5 μm | Commercially available FEP film | Without oil pump | 144 min |

| [32] | 30 μm | Commercially available FEP film | Without oil pump | 378 min |

| [33] | 1.1 μm | Teflon/PAI composite membrane | With oil pump | 120 min |

| This work | 3 μm | Custom-fabricated AF2400-coated ceramic membrane | Without oil pump | 72.5 min |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dou, W.; Sun, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Tao, K.; Li, Y. In Situ Oil–Gas Separator Enabled Carrier-Free Photoacoustic Sensing of Acetylene. Sensors 2026, 26, 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030946

Dou W, Sun X, Gao Y, Wang S, Tao K, Li Y. In Situ Oil–Gas Separator Enabled Carrier-Free Photoacoustic Sensing of Acetylene. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):946. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030946

Chicago/Turabian StyleDou, Weitao, Xitong Sun, Yanping Gao, Shudong Wang, Kai Tao, and Yunjia Li. 2026. "In Situ Oil–Gas Separator Enabled Carrier-Free Photoacoustic Sensing of Acetylene" Sensors 26, no. 3: 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030946

APA StyleDou, W., Sun, X., Gao, Y., Wang, S., Tao, K., & Li, Y. (2026). In Situ Oil–Gas Separator Enabled Carrier-Free Photoacoustic Sensing of Acetylene. Sensors, 26(3), 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030946