Trajectory Optimization of Airport Surface Guidance Operations for Unmanned Guidance Vehicles

Highlights

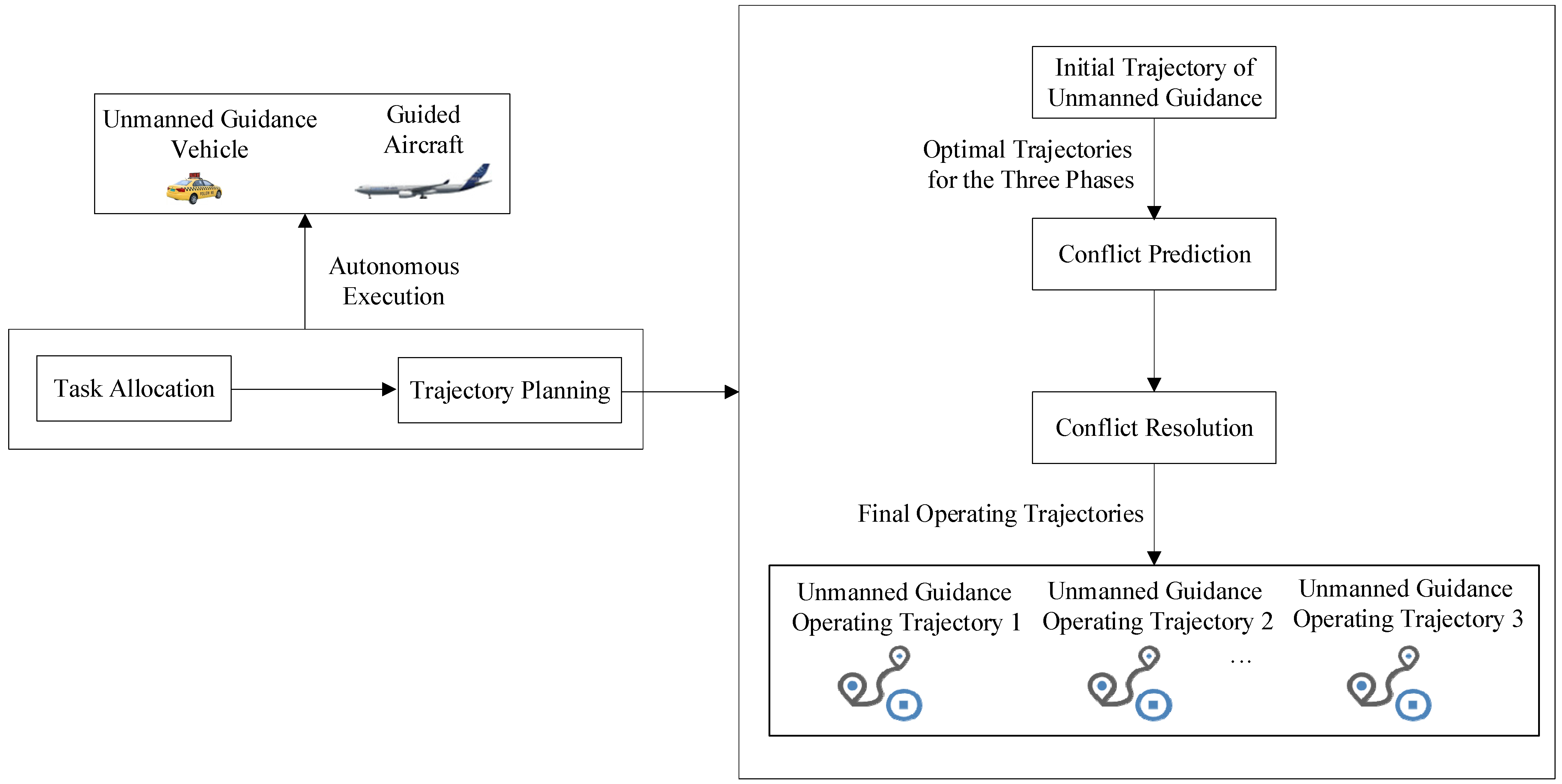

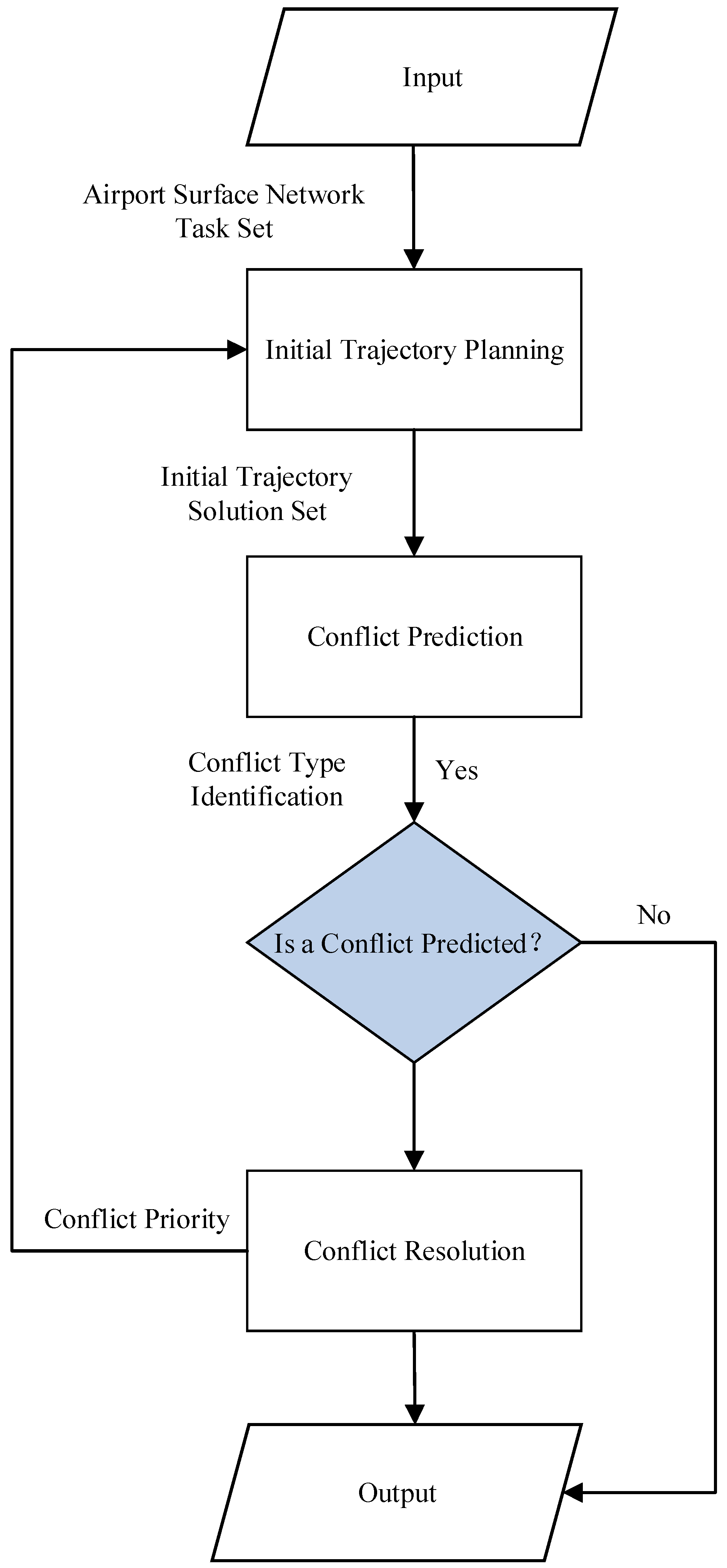

- A three-stage trajectory planning framework is proposed for airport surface unmanned guidance operations, which operates under operational safety constraints and integrates improved A* trajectory planning, time-window-based conflict prediction, and priority-driven conflict resolution.

- By incorporating speed-profile-based time calculation and spatiotemporal occupancy modeling of guidance vehicles and guidance units, the proposed method enables conflict-free trajectory generation while enhancing taxiing efficiency and reducing energy consumption.

- The results demonstrate that trajectory planning based on spatiotemporal state information—derived from speed profiles and time-window modeling—can effectively support safe and efficient unmanned guidance operations conducted by guidance vehicles and guidance units on airport surfaces.

- The proposed framework provides a practical decision-support framework for intelligent airport surface operations, supporting the deployment of electric unmanned guidance vehicles contributing to low-carbon and high-efficiency airport ground movement management.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Analysis

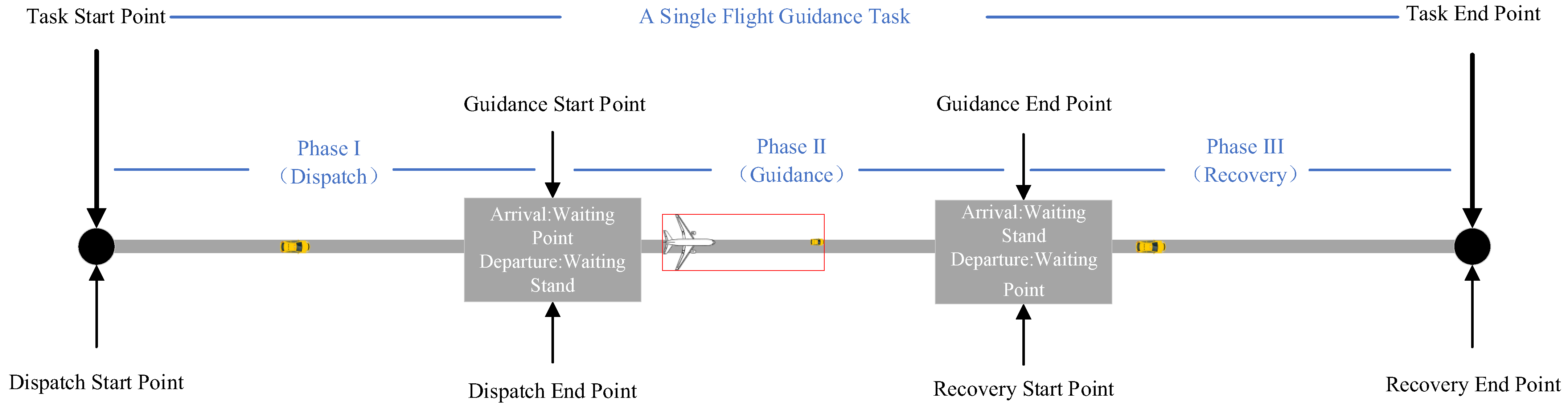

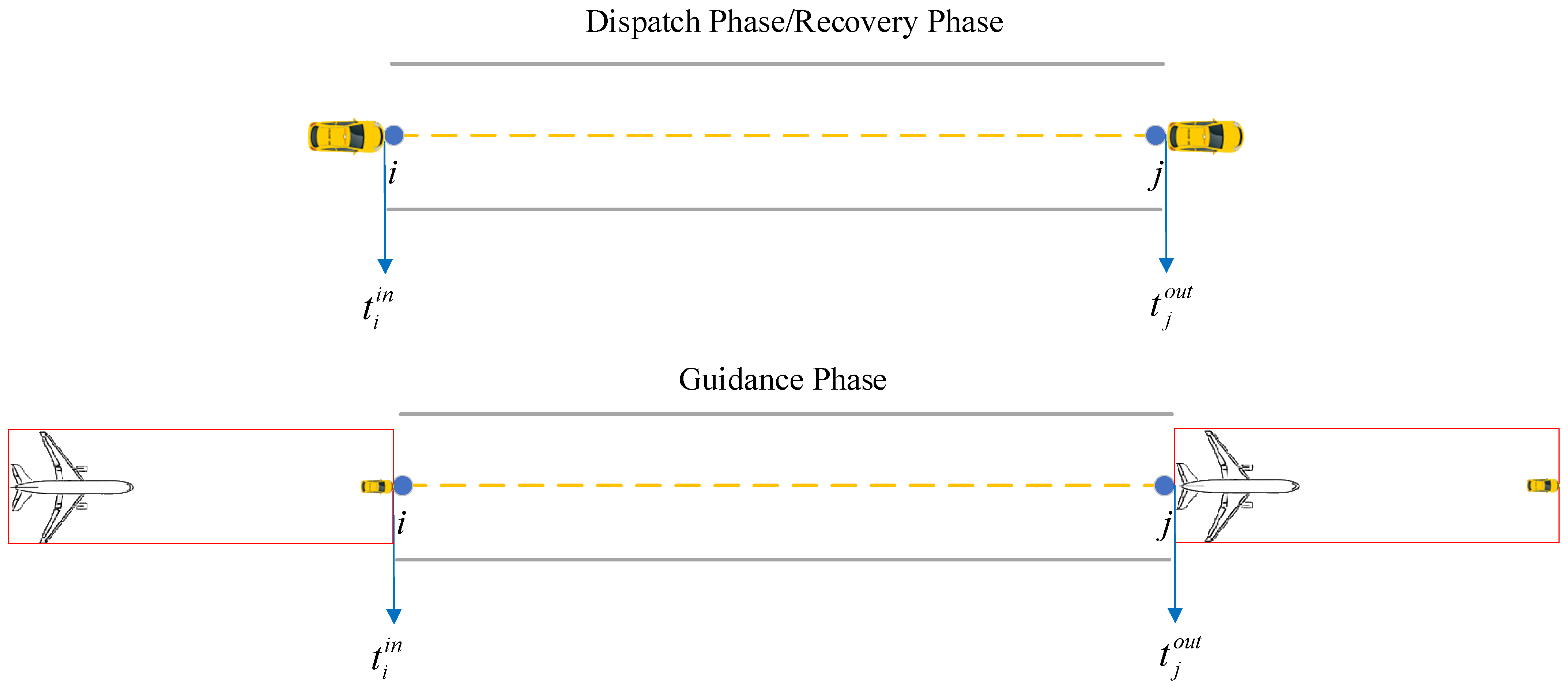

- During the dispatch and recovery phases, the unmanned guidance vehicle operates entirely within the airport surface taxiway network.

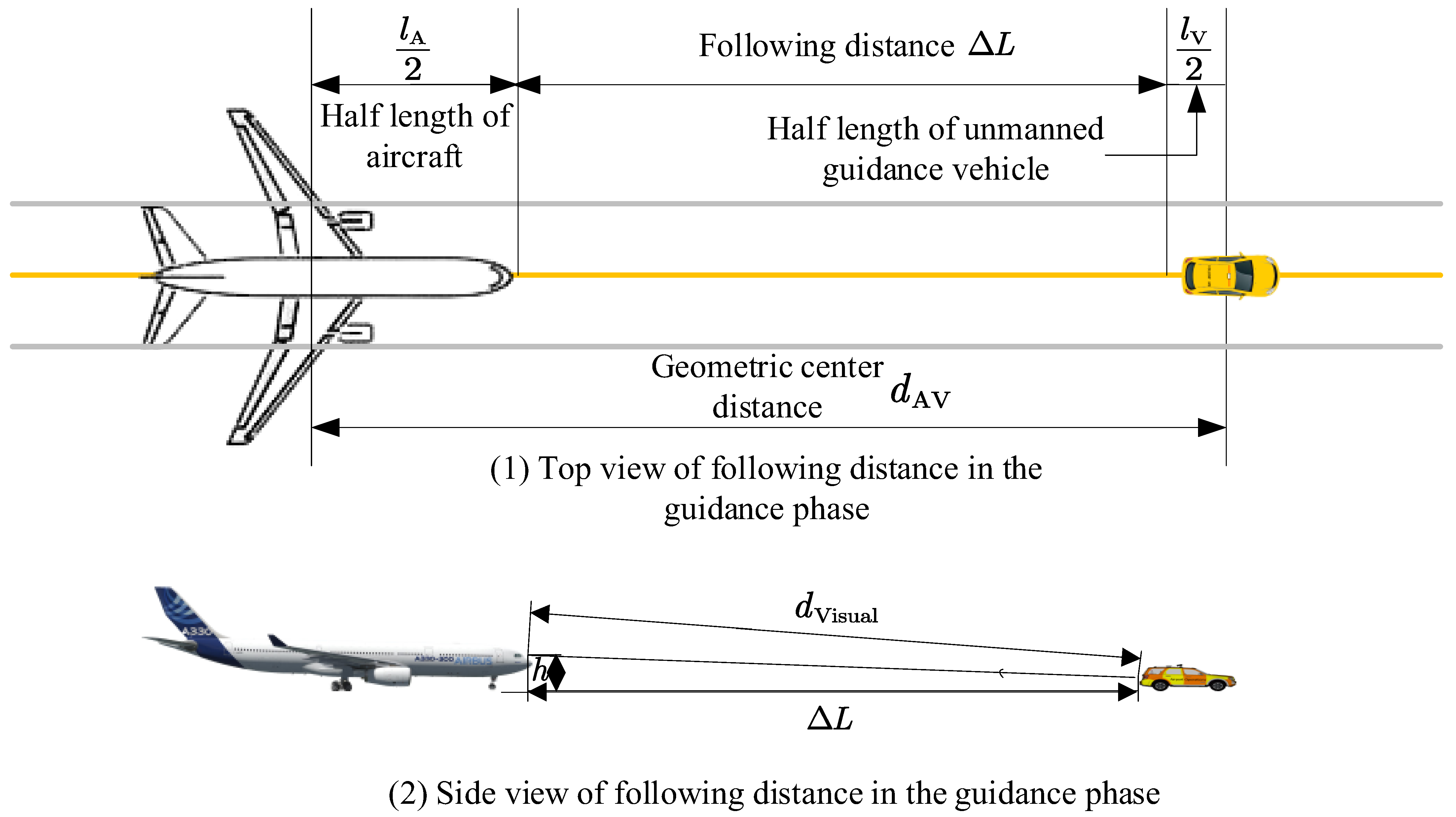

- During the guidance phase, the unmanned guidance vehicle and the guided aircraft are regarded as a single kinematic entity, hereinafter referred to as the “Guidance Unit.” Accordingly, the airport surface trajectory planning for unmanned guidance primarily aims to assign appropriate unmanned guidance vehicles to arriving and departing flights within a given time horizon, and to determine the corresponding travel routes and the passage times at key waypoints for each unmanned guidance vehicle or guidance unit, so as to ensure the minimum taxiing time and conflict-free surface operations.

3. Unmanned Guidance Unit

4. Mathematical Description of the Unmanned Guidance Trajectory Planning Problem

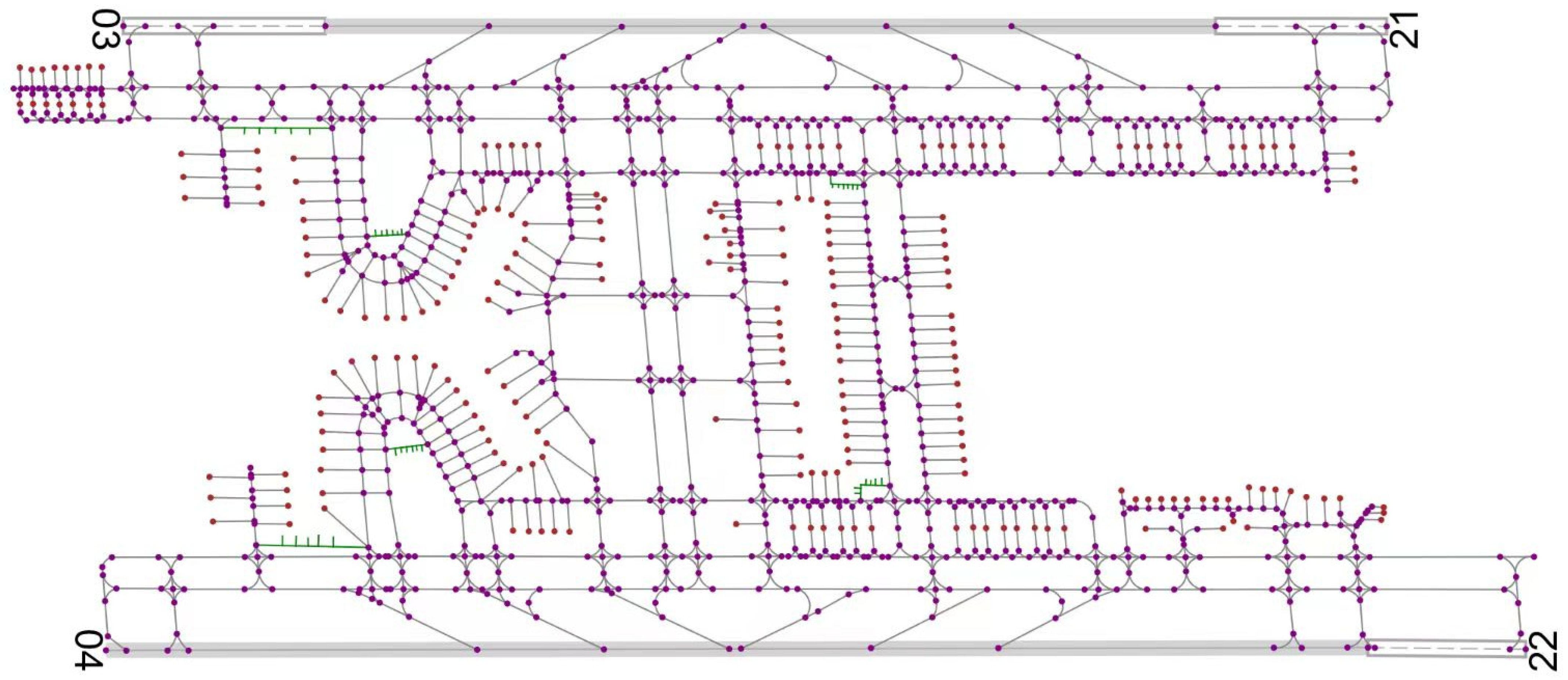

4.1. Airport Runway and Taxiway Network

4.2. Description of the Unmanned Guidance Process

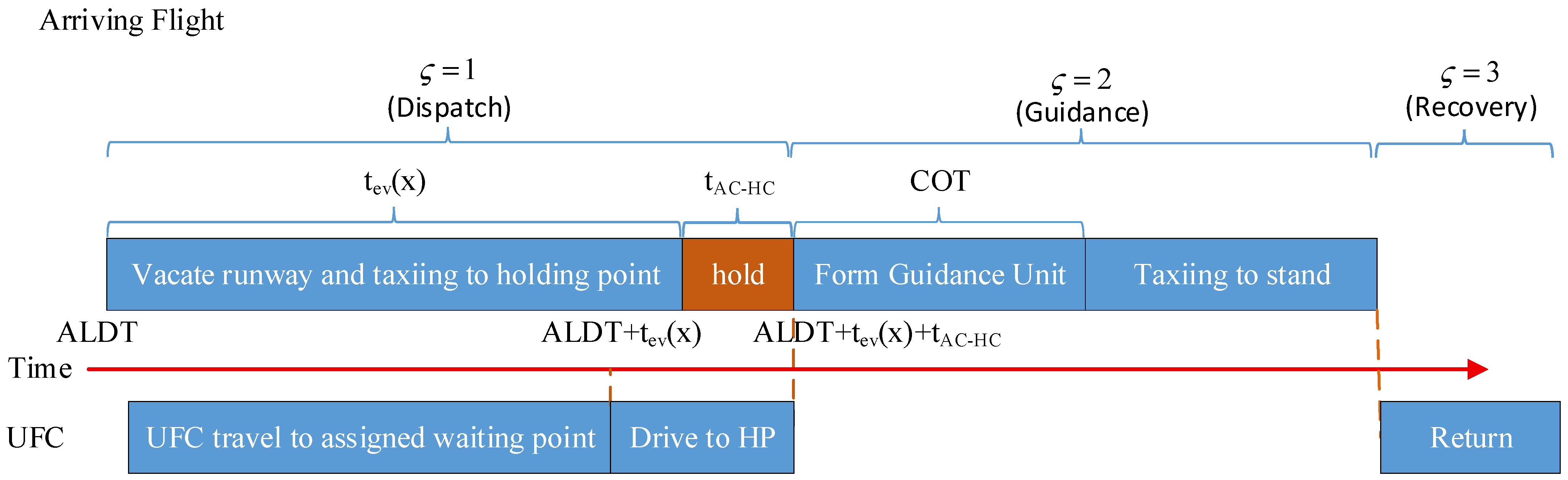

4.2.1. Guidance Process for Arriving Flights

4.2.2. Guidance Process for Departing Flights

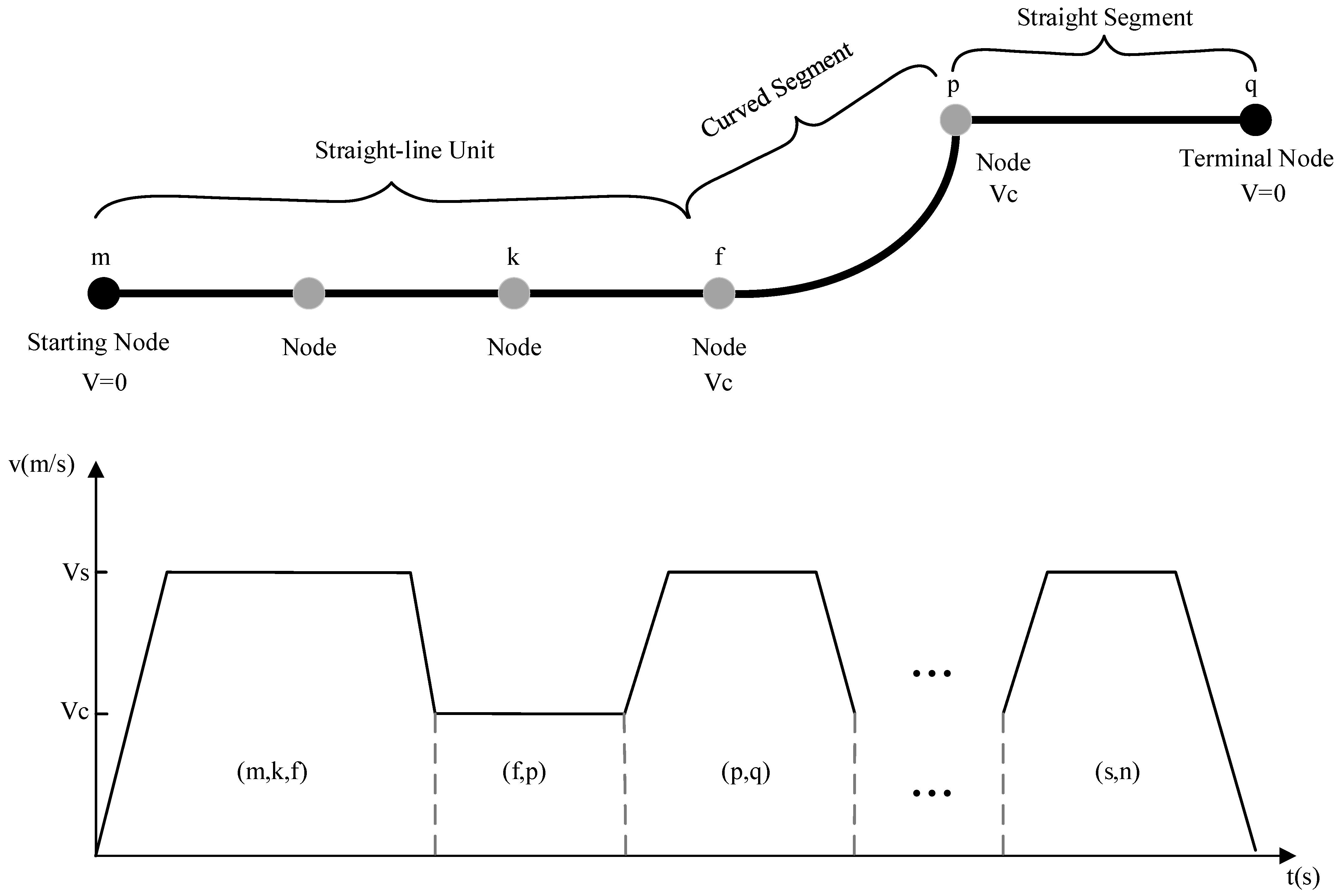

4.3. Speed Profile Design for Unmanned Guidance Operations

| Algorithm 1 Speed profile computation for unmanned guidance unit |

| Input: Path of segments , ; Segment parameters (length , , , , , , ); Output: Speed profile set for curves. do then ; ; Formula (2); ←Formula (1); Formula (3); ←Formula (4); ; ; then ←constant value; ; 12: end if 13: end for 14: return complete speed profile for all segments. |

4.4. Energy Consumption Model for Unmanned Guidance

5. Trajectory Planning Model for Unmanned Guidance

| Algorithm 2 Trajectory planning for unmanned guidance |

| Input: ; —set of assigned unmanned guidance; Segment parameters (length , , , , , , ); Time-window and clearance parameters Heuristic function and penalty weights of the improved A*. Output: —conflict-free trajectories with time windows. do 2: invoke Algorithm 3 to generate the initial path of using the speed-profile model 5: end for 6: repeat 7: invoke Conflict-Prediction Algorithm 4, Algorithm 5 and Algorithm 6 then 10: invoke Algorithm 7 11: end if |

5.1. Optimization Objectives

- 1.

- For a single guidance task , if it is performed by an unmanned guidance vehicle , the total task duration can be expressed as . For each individual guidance task, the optimization objective of the unmanned guidance vehicle trajectory planning is to minimize the maximum guidance duration, which can be formulated aswhere denotes the travel time of vehicle when performing guidance task from node to node ; indicates that vehicle is assigned to perform the guidance task from node to node ; otherwise, .

- 2.

- For a single guidance vehicle, if multiple guidance tasks forming a task chain , the optimization objective for minimizing the task guidance duration is to minimize the total completion time of all tasks in the chain [30].where denotes the travel time required between two consecutive guidance tasks. Each flight is associated with a single guidance task b∈B. Each guidance task is composed of three sequential phases, namely dispatch, guidance, and recovery.

- 3.

- For a single guidance task , the energy consumption of this task includes the energy consumed by the unmanned guidance vehicle and the guided aircraft forming the guidance unit. The optimization objective of unmanned guidance energy consumption is to minimize the maximum energy consumption during the guidance process.where represents the energy consumption of the vehicle when performing guidance task during the current phase, and represents the energy consumption of the guidance task from node to node during the current phase.

5.2. Constraints

- 4.

- During a single guidance task, each vertex in can be visited only once.

- 5.

- In a single guidance task, the starting node of each segment must be visited before its ending nodewhere denotes the service start time at node when performing task ; denotes the service start time at node when performing task .

- 6.

- In a single guidance task, the start time of the ending node of each segment shall be at least equal to the start time of its starting node plus the travel time from node to nodewhere is a sufficiently large constant.

- 7.

- The three phases of a guidance task are continuous, and the ending node of the current phase shall be the starting node of the next phase of the guidance task.where denotes the ending node of the dispatch phase, denotes the starting node of the guidance phase, denotes the ending node of the guidance phase, and denotes the starting node of the recovery phase.

6. Trajectory Planning Algorithm for Unmanned Guidance

6.1. Initial Trajectory Planning for Unmanned Guidance

6.1.1. Initial Trajectory Planning for Unmanned Guidance Based on the Improved A* Algorithm

6.1.2. Time Window Calculation

| Algorithm 3 Improved A* algorithm for unmanned guidance vehicle trajectory planning |

| Input: ; ); ; Heuristic and penalty weights ω in Formulas (19) and (20) Output: Optimal path . do with minimum Formula (19) do using Formula (22) using Formulas (19) and (20) 7: if time-window constraint violated then skip 9: end for from Open to Closed then break 12: end while 13: reconstruct and output the optimal trajectory with |

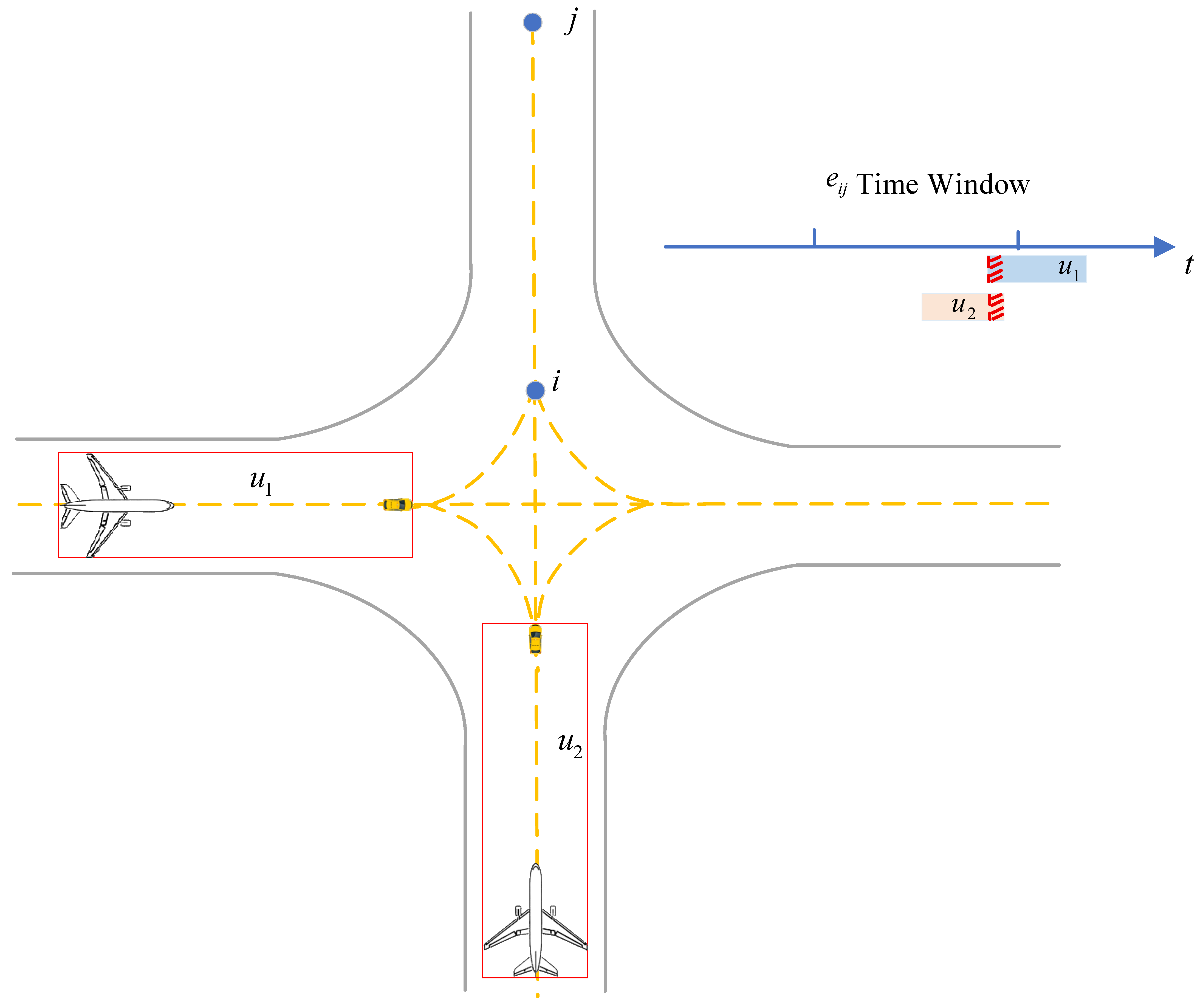

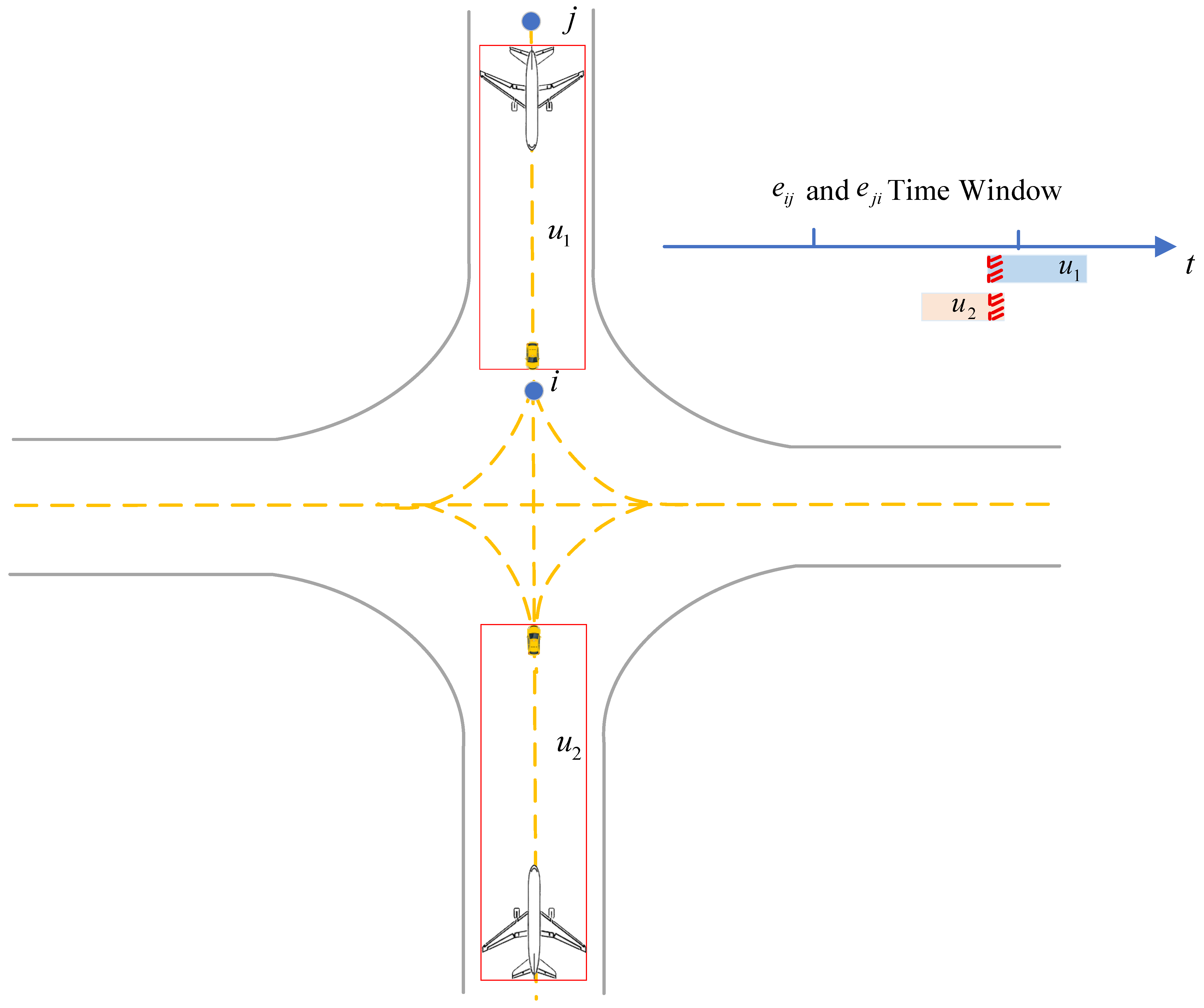

6.2. Conflict Prediction

- Crossing Conflict

| Algorithm 4 Crossing-Conflict Prediction for Unmanned Guidance |

| Input: —airport surface directed graph; —set of assigned unmanned guidance; . Output: —set of crossing conflicts. do 4: sort enter/leave events by time ascending do then insert 8: else remove from 10: end for 11: end for |

- 2.

- Head-on Conflict

| Algorithm 5 Head-on conflict prediction for unmanned guidance |

| Input: —airport surface directed graph; —set of assigned unmanned guidance; . Output: —set of head-on conflicts. do 4: sort events by time do according to enter/leave 9: end for 10: end for |

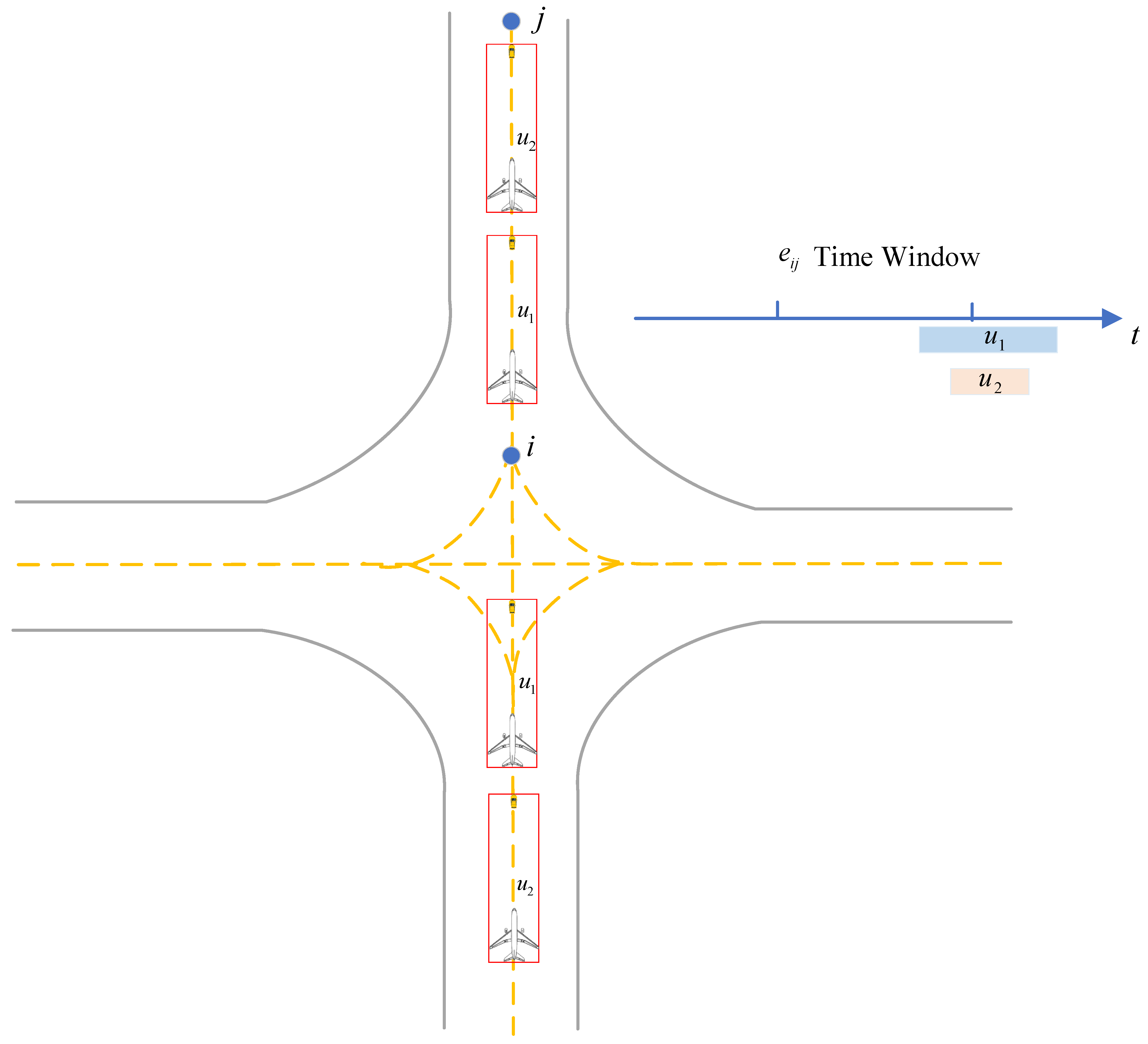

- 3.

- Overtaking Conflict

| Algorithm 6 Overtaking conflict detection for unmanned guidance |

| Input: —airport surface directed graph; —set of assigned unmanned guidance; . Output: —set of overtaking conflicts. do in the same direction. do then 9: end if 10: end for 11: end for |

6.3. Conflict Resolution

| Algorithm 7 Conflict resolution for unmanned guidance |

| Input: —initial trajectory set with edge-occupancy time —conflict set; —conflict unmanned guidance; Output: —conflict-free trajectory set. 1: sort by the start time in Formula (28) do 3: obtain unmanned guidance Uk and sort by Formula (28): trajectory unchanged 5: activate the corresponding conflict-penalty weight in Formula (29) do ←Formulas (20) and (21) 9: end for is resolved then remove it from 11: end for |

7. Case Study

7.1. Case Design

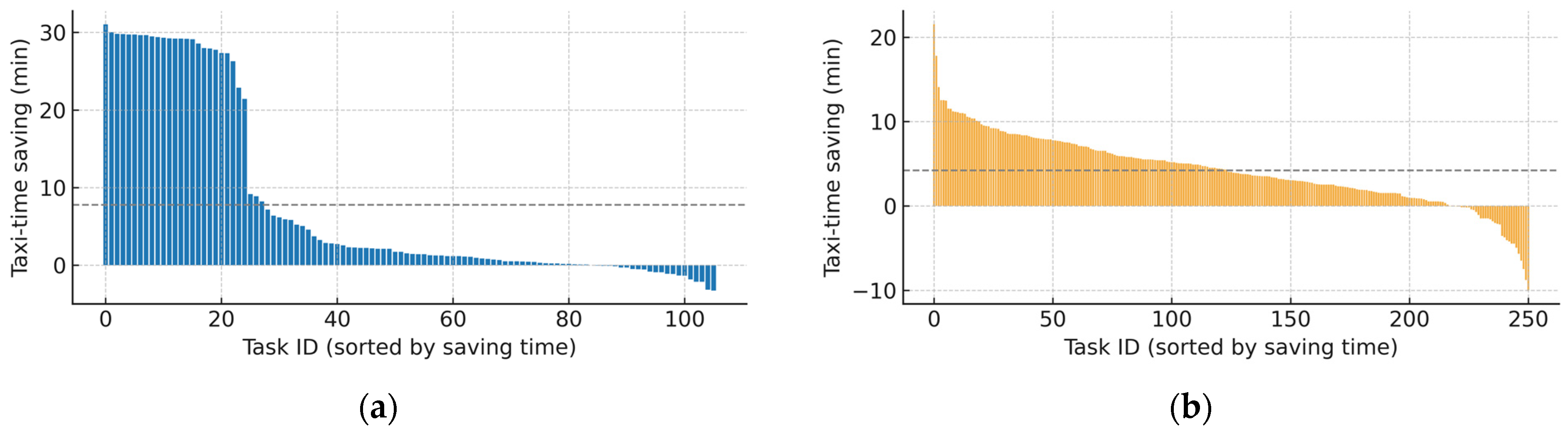

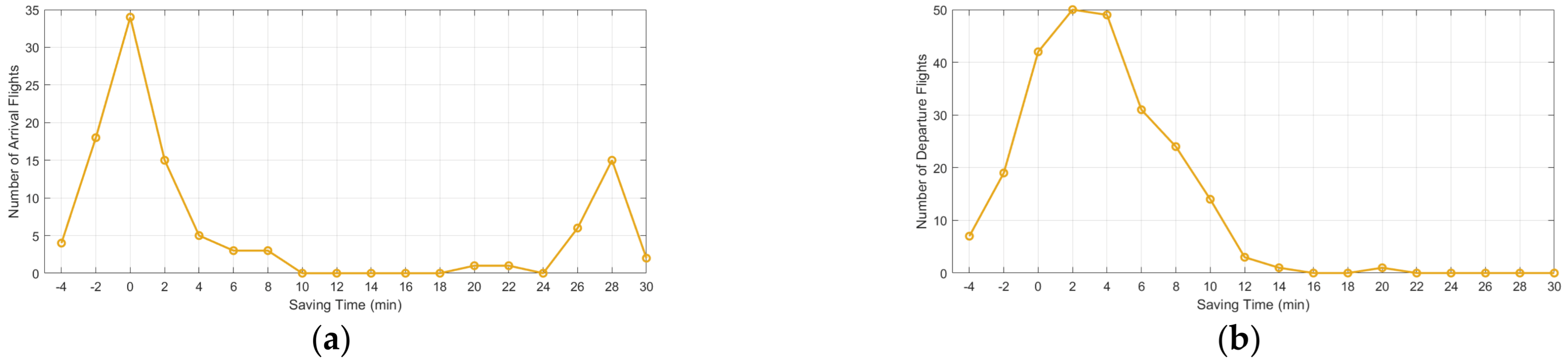

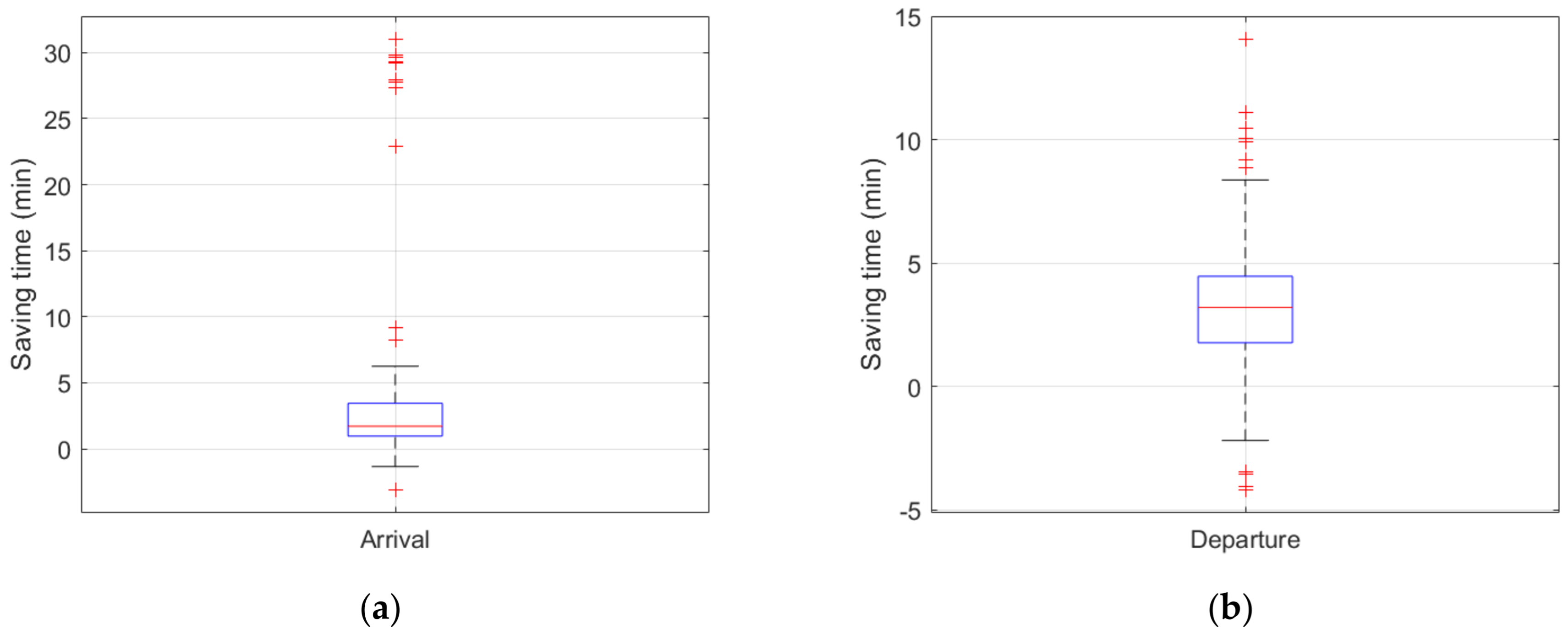

7.2. Analysis of Guidance Time Results

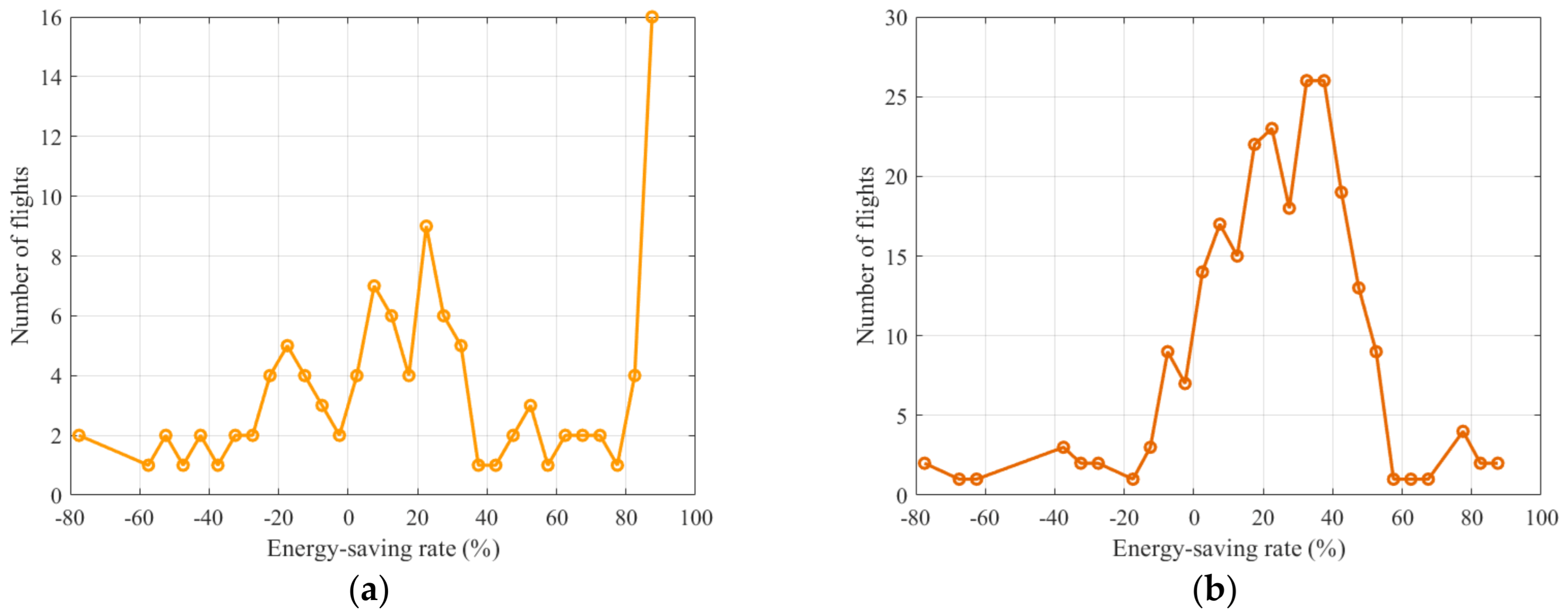

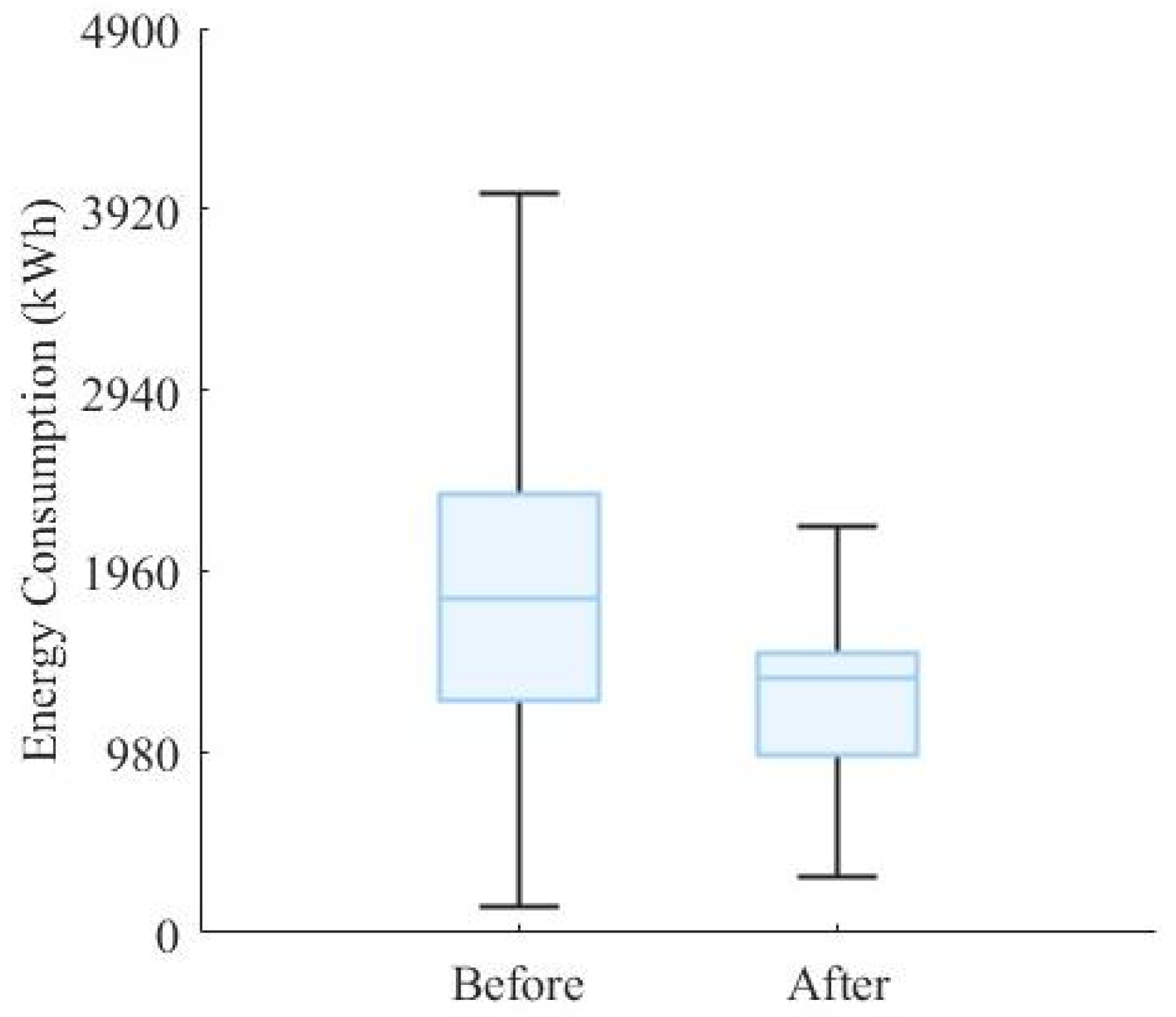

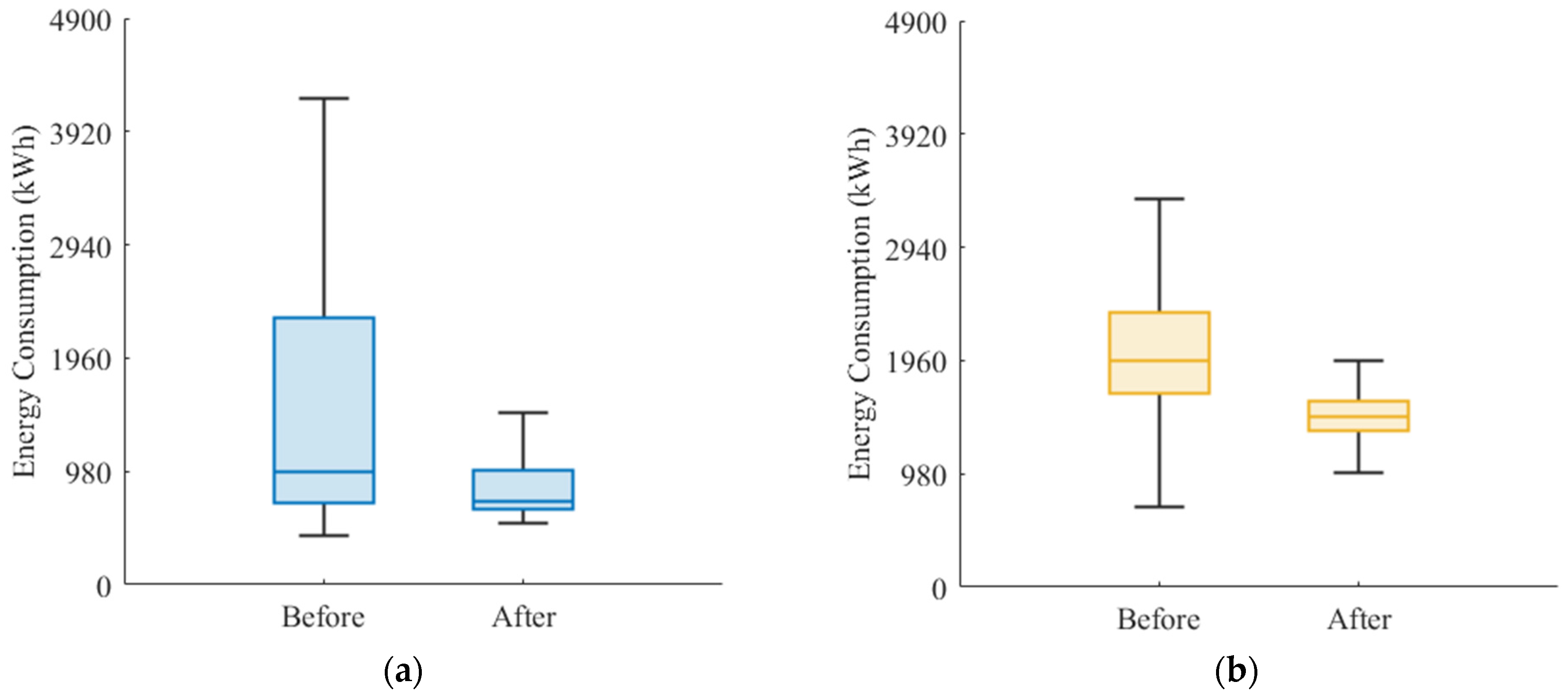

7.3. Energy Consumption Analysis

8. Conclusions

- For the problem of unmanned guidance trajectory planning and energy optimization on the airport surface, a speed profile model and an energy consumption model for unmanned guidance are proposed, enabling the joint optimization of both aspects; By incorporating the actual operational rules of unmanned guidance on the airport surface, the improved A* algorithm is employed to digitalize these operational constraints. Considering the three types of conflicts that may occur during unmanned guidance operations on the airport surface, conflicts are identified through time-window determination; furthermore, a task-priority-based conflict-resolution algorithm is designed.

- A case study is conducted based on a major airport in Southwest China. The results indicate that the improved A* trajectory planning algorithm substantially enhances the operational efficiency of airport surface guidance. With the introduction of unmanned guidance vehicles and the adoption of the proposed algorithm, guided taxiing effectively reduces both taxiing time and energy consumption, with 79% of arriving flights and 87% of departing flights achieving reductions in operational time. In terms of airport surface energy consumption, 71% of arriving flights and 85% of departing flights achieve reductions in energy consumption during the guidance phase. Overall, with the application of the proposed unmanned guidance trajectory-planning model, the total operational efficiency increases by 43.65%, and the total energy consumption during the guidance phase is reduced by 34.52%, thereby achieving coordinated optimization of operational efficiency and energy consumption.

- Future research may investigate trajectory planning strategies for scenarios in which flights experience delays or unmanned guidance vehicles encounter unexpected events, in order to enhance the robustness of the proposed algorithms and models.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| The runway–taxiway system network | — | |

| Set of runway entry, runway exit, and aircraft stand nodes | — | |

| Set of parking positions | — | |

| Set of waiting points near stands or runway exits | — | |

| Set of taxiway intersections | — | |

| Set of directed edges | — | |

| Set of runway edges | — | |

| Set of taxiway edges | — | |

| Set of stand- and waiting-point edges | — |

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| set of flights considered in the guidance operation | — | |

| set of guidance tasks | — | |

| set of guidance tasks for arriving aircraft | — | |

| set of guidance tasks for departing aircraft | — | |

| unmanned guidance (unmanned guidance vehicle and guidance unit) | — | |

| set of unmanned guidance vehicles | — | |

| for dispatch, guidance, and recovery) | — |

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| The starting node of the current phase | — | |

| The ending node of the current phase | — | |

| Time domain | — | |

| The starting time of the current phase |

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| The length of each edge in the network | ||

| The operating taxi speed adopted on each edge |

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Tuple representation of a guidance task | — |

References

- Yuan, D.; Zhu, X.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, Q. Integrated optimization of scheduling for unmanned follow-me cars on airport surface. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hong, S.; Zio, E.; Liu, J. Integrated fault estimation and fault-tolerant control for a flexible regional aircraft. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ding, M.; Wang, B.; Chen, Q. Conflict-free time-based trajectory planning for aircraft taxi automation with refined taxiway modeling. J. Adv. Transp. 2016, 50, 326–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ding, M.; Zuo, H. Improved approach for time-based taxi trajectory planning towards conflict-free, efficient and fluent airport ground movement. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 12, 1360–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zuo, H.; Wang, B.; Zeng, L.; Sun, Z. Zone control based aircraft ground movement trajectory optimization model. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2016, 38, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Pazhooh, S.F.; Shemirani, H.S. An Efficient Continuous-Time MILP for Integrated Aircraft Hangar Scheduling and Layout. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.02640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, X.; He, X. Vibration-theoretic approach to vulnerability analysis of nonlinear vehicle platoons. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 11334–11344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jiang, X. Research on taxiway path optimization based on conflict detection. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Brownlee, A.E.; Weiszer, M.; Woodward, J.R.; Mahfouf, M.; Chen, J. A chance-constrained programming model for airport ground movement optimisation with taxi time uncertainties. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 132, 103382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuge, J.; Liang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; Wu, J. Aircraft Ground Taxiing Deduction and Conflict Early Warning Method Based on Control Command Information. Transp. Res. Rec. 2024, 2678, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, D.; Chen, H.; Zhou, T. A conflict resolution strategy at a taxiway intersection by combining a Monte Carlo tree search with prior knowledge. Aerospace 2023, 10, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipp, T.; Boyd, S. Minimum-time speed optimisation over a fixed path. Int. J. Control 2014, 87, 1297–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ding, M.; Zuo, H.; Chen, J.; Weiszer, M.; Qian, X.; Burke, E.K. An online speed profile generation approach for efficient airport ground movement. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 93, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiszer, M.; Burke, E.K.; Chen, J. Multi-objective routing and scheduling for airport ground movement. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 119, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evertse, C.; Visser, H.G. Real-time airport surface movement planning: Minimizing aircraft emissions. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 79, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Sun, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, J.-C.; Zhang, H.-F.; Tsai, S. An empirical study on low emission taxiing path optimization of aircrafts on airport surfaces from the perspective of reducing carbon emissions. Energies 2019, 12, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhu, Q.; Qin, B.; Song, R.; Li, Z. UAV path planning based on third-party risk modeling. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Zhong, Y.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Y.; Jin, Y.; Du, X.; Tang, K.; Huang, T. Trajectory Planning for Unmanned Vehicles on Airport Apron Under Aircraft–Vehicle–Airfield Collaboration. Sensors 2024, 25, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L. Bi-objective optimization for electric vehicle scheduling under vehicle-to-grid integration. Inf. Sci. 2025, 723, 122649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wang, J. Globally energy-optimal speed planning for road vehicles on a given route. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 93, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Fajri, P.; Sabzehgar, R.; Harirchi, F. Autonomous Electric Vehicle Route Optimization Considering Regenerative Braking Dynamic Low-Speed Boundary. Algorithms 2023, 16, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiszer, M.; Chen, J.; Stewart, P. A real-time active routing approach via a database for airport surface movement. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2015, 58, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Sarker, A.; Shen, H. Velocity optimization of pure electric vehicles with traffic dynamics and driving safety considerations. ACM Trans. Internet Things 2021, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, H.; Konur, D.; Vaz, W.S.; Koylu, Ü.Ö. A realistic driving profile optimization for electric vehicles. In Proceedings of the IIE Annual Conference and Expo, Anaheim, CA, USA, 21–24 May 2016; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gulan, K.; Cotilla-Sanchez, E.; Cao, Y. Charging analysis of ground support vehicles in an electrified airport. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), Detroit, MI, USA, 19–21 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Z. Modeling and Optimization of Trip Level Energy Consumption and Charging Management for Connected Automated Electric Vehicles; Idaho National Lab (INL): Idaho Falls, ID, USA, 2019.

- Qi, R.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Jin, H.; Han, Y.-Y. QMOEA: A Q-learning-based multiobjective evolutionary algorithm for solving time-dependent green vehicle routing problems with time windows. Inf. Sci. 2022, 608, 178–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoleris, T.; Gupta, G.; Kistler, M. Detailed estimation of fuel consumption and emissions during aircraft taxi operations at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2011, 16, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, R.; Batra, A. Assessing the environmental impact of aircraft taxiing technologies. In Proceedings of the 32nd Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences, Shanghai, China, 6–10 September 2021; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, F.; Brito, M.; Louro, P.; Gama, S. Genetic Algorithm Optimization of Sales Routes with Time and Workload Objectives. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Liang, J.; He, D. Unmanned ground vehicle path planning based on improved DRL algorithm. Electronics 2024, 13, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afriyie, I. Advancing Unmanned Ground Vehicle Path Planning with Quantified Map Uncertainty. Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoseiri, K.; Ghannadpour, S.F. Multi-objective vehicle routing problem with time windows using goal programming and genetic algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2010, 10, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrochers, M.; Desrosiers, J.; Solomon, M. A new optimization algorithm for the vehicle routing problem with time windows. Oper. Res. 1992, 40, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałasz, B.; Waluś, K.J.; Warguła, Ł. The determination of the rolling resistance coefficient of a passenger vehicle with the use of selected road tests methods. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 254, 04006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hucho, W.H. (Ed.) Aerodynamics of Road Vehicles: From Fluid Mechanics to Vehicle Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- EUROCONTROL. European Airline Delay Cost Reference Values; EUROCONTROL Experimental Centre: Brétigny-sur-Orge, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. Bi-objective optimization strategy of energy consumption and shift shock based driving cycle-aware bias coefficients for a novel dual-motor electric vehicle. Energy 2022, 249, 123596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulik, B.; Kaur, S.; Ijaz, M. Optimized Energy Consumption of Electric Vehicles with Driving Pattern Recognition for Real Driving Scenarios. Algorithms 2025, 18, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, K.; Roling, P.; Mouli, G.R.C.; Atasoy, B. The impact of transitioning to electric Ground Support Equipment on the fleet capacity and energy demand at airports. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 21, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, H.; Balakrishnan, H. Estimation of aircraft taxi fuel burn using flight data recorder archives. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2012, 17, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Robby, K.; Rane, J.; Das, A.; Podkaminer, K.; Borlaug, B. Hourly Load Profile Dataset for Electric Airport Ground Support Equipment in the United States; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2025.

- Jarry, G.; Very, P.; Dalmau, R.; Delahaye, D.; Houdant, A. On the Detection of Aircraft Single Engine Taxi using Deep Learning Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.07727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Meaning | Unit | Default Value | Recommended Range | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight of reverse-driving conflict cost | — | 100 | 80–150 | Penalty for reversing or wrong-way driving paths | Model assumption | |

| Weight of turning conflict cost | — | 20 | 10–30 | Penalty for frequent sharp turns or continuous turning | Model assumption | |

| Weight of crossing conflict cost | — | 20 | 10–30 | Penalty to discourage paths passing through busy intersections | Model assumption | |

| Weight of head-on conflict cost | — | 40 | 30–60 | Increased penalty for head-on lane-occupying paths | Model assumption | |

| Weight of overtaking conflict cost | — | 20 | 10–30 | Penalty to prevent same-direction overtaking and maintain a safety following distance | Model assumption | |

| Buffer time between nodes/segments | s | 5 | 3–10 | Safety buffer for time-window propagation | Derived from speed profile and motion constraints | |

| Departure time of the unmanned guidance vehicle from a node | s | 15 | — | Used for time-window calculation | Computed value | |

| Equivalent mass of the unmanned guidance vehicle | kg | 1500 | 1200–1800 | Constant term used in the kinetic-energy component | Typical engineering value | |

| Gravitational acceleration | m·s−2 | 9.81 | — | Constant | Standard constant | |

| Rolling resistance coefficient of the unmanned guidance vehicle | — | 0.015 | 0.01–0.02 | Smooth asphalt/cement pavement | Literature-based [35] | |

| Rolling resistance coefficient of the Follow-Me vehicle | — | 0.018 | 0.016–0.020 | Smooth asphalt/cement pavement | Literature-based [35] | |

| Air density | kg·m−3 | 1.225 | 1.1–1.3 | Sea level, 15 °C | Standard constant | |

| Aerodynamic drag coefficient x frontal area of the unmanned guidance vehicle | m2 | 0.80 | 0.7–1.2 | Determined by vehicle body shape | Literature-based [36] | |

| Aerodynamic drag coefficient x frontal area of the Follow-Me vehicle | m2 | 0.90 | 0.80–0.95 | Determined by vehicle body shape | Literature-based [36] | |

| Transmission efficiency of the unmanned guidance vehicle | — | 0.90 | 0.85–0.95 | Electric drivetrain efficiency | Typical engineering value | |

| Transmission efficiency of the Follow-Me vehicle | — | 0.25 | 0.20–0.30 | Fuel drivetrain efficiency | Typical engineering value | |

| Lower heating value of aviation kerosene | MJ·kg−1 | 43.0 | 42.8–43.3 | Used to convert fuel mass flow rate into energy consumption | Standard fuel property | |

| Fuel burn rate during taxiing (narrow-body aircraft) | kg·s−1 | 0.195 | 0.15–0.25 | Narrowbody | Literature-based [37] | |

| Fuel burn rate during taxiing (wide-body aircraft) | kg·s−1 | 0.430 | 0.35–0.50 | Widebody | Literature-based [37] | |

| Fuel burn rate during taxiing (regional aircraft) | kg·s−1 | 0.137 | 0.10–0.18 | Regional | Literature-based [37] |

| Flight Number | Arrival/Departure Type | Arrival/Departure Time | Stand Arrival/Pushback Time | Runway Used | Aircraft Type | Stand Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HO1017 | Arrival | 00:03 | 00:11 | 22 | A321 | 142 |

| GJ8872 | Arrival | 00:08 | 00:19 | 22 | 3NEO | 168 |

| KY8348 | Arrival | 00:00 | 00:25 | 22 | B737 | 159 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| BK2898 | Departure | 23:19 | 23:30 | 21 | B738 | 156 |

| MU9951 | Departure | 23:21 | 23:33 | 22 | B738 | 123 |

| CF9017 | Departure | 23:59 | 00:12 | 22 | B738 | 724 |

| Phase Type | Dispatch Phase | Guidance Phase | Recovery Phase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrival/Departure | ||||

| Arrival | 332.2574 min (5.54 h) | 587.7280 min (9.80 h) | 474.8694 min (7.914 h) | |

| Departure | 679.9318 min (11.33 h) | 2518.5314 min (41.98 h) | 1716.8740 min (28.614 h) | |

| Total | 1012.1892 min (16.87 h) | 3106.2631 min (51.78 h) | 2191.7434 min (36.53 h) | |

| Scenario | Number of Tasks | Conflict Resolution Success Rate | Average Operation Time Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (full day) | 357 | 100% | 43.65% |

| Peak (11:00–12:00) | 27 | 100% | 27.26% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, T.; Wang, K.; Tang, K.; Yuan, D.; Zhu, X. Trajectory Optimization of Airport Surface Guidance Operations for Unmanned Guidance Vehicles. Sensors 2026, 26, 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030931

Sun T, Wang K, Tang K, Yuan D, Zhu X. Trajectory Optimization of Airport Surface Guidance Operations for Unmanned Guidance Vehicles. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):931. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030931

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Tianping, Kai Wang, Ke Tang, Dezhou Yuan, and Xinping Zhu. 2026. "Trajectory Optimization of Airport Surface Guidance Operations for Unmanned Guidance Vehicles" Sensors 26, no. 3: 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030931

APA StyleSun, T., Wang, K., Tang, K., Yuan, D., & Zhu, X. (2026). Trajectory Optimization of Airport Surface Guidance Operations for Unmanned Guidance Vehicles. Sensors, 26(3), 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030931