Mapping Privacy Vulnerabilities in Local Area Network (LAN) Environments

Abstract

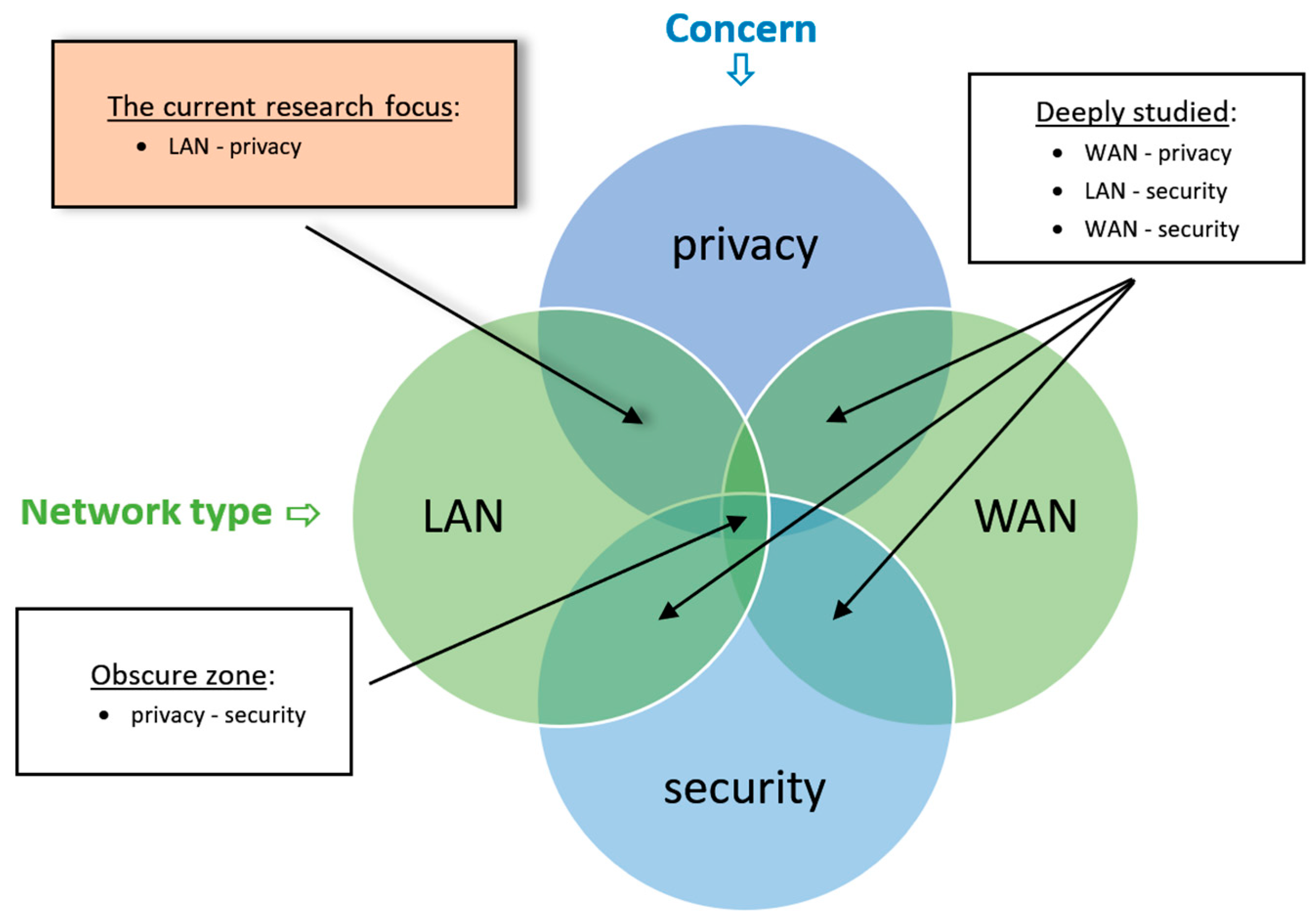

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

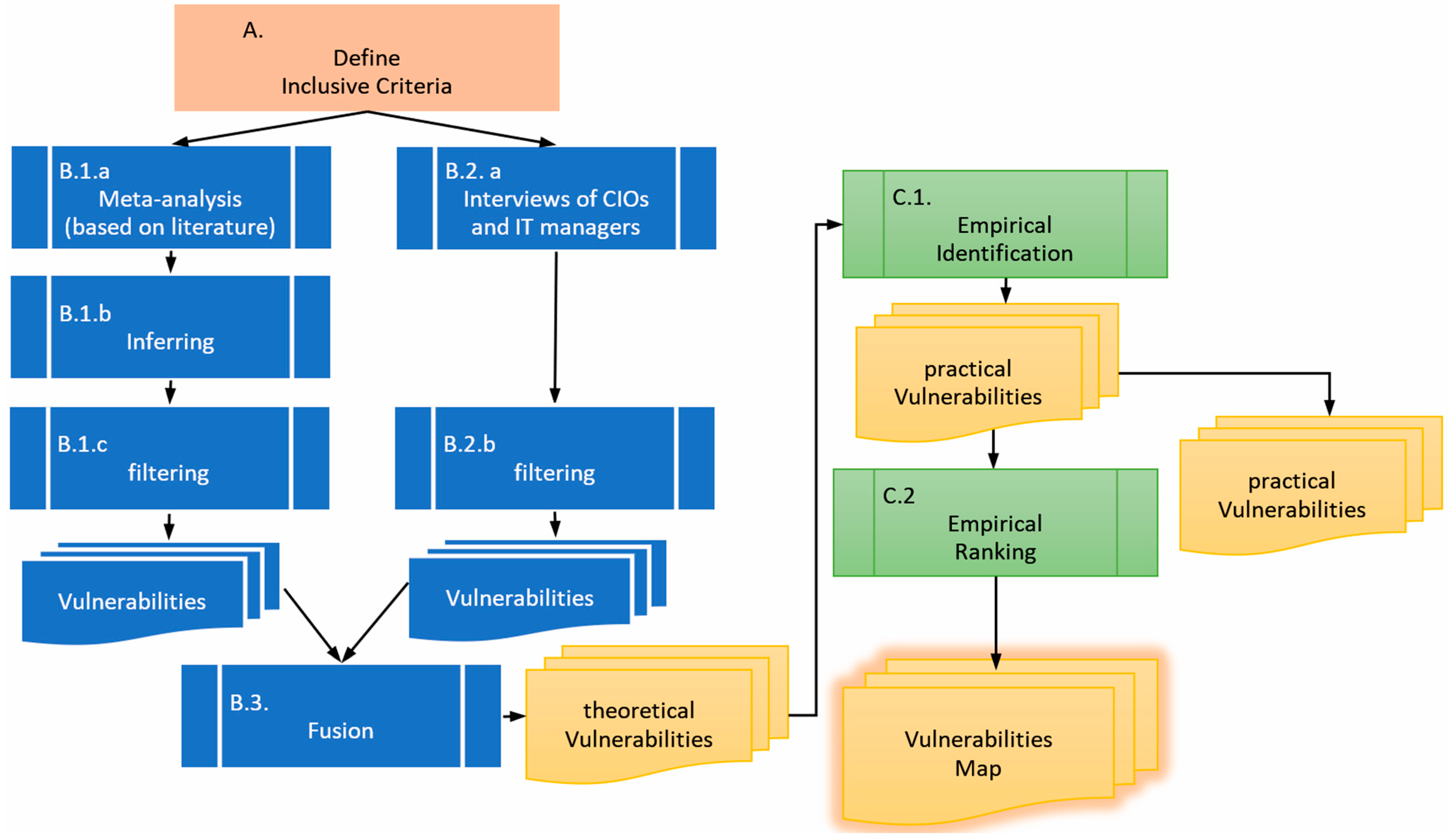

3. Methodology

3.1. The Vulnerability Inclusive Criteria

- a.

- LAN environment:

- b.

- Non-administrative rights:

- c.

- No hacking:

- d.

- No password breach:

3.2. Vulnerabilities’ Identification

- Interviews of CIOs (Chief Information Officer) and IT (Information Technology) experts on the subject of privacy risk, of which they are aware and/or that occur under their management. Since intuitively, when the term “privacy” is mentioned, the mind wanders to the Internet (the WAN). We expected that most of the vulnerabilities that they would raise would not fall within the criteria (especially criterion a); thus, the results needed to be filtered accordingly.

- Meta-analysis based on the relevant literature. Since the literature primarily does not deal directly with the current research problem, and in most cases security and privacy are confused, or “LAN” issues are actually Internet (WAN) issues, the criteria filter must be applied here as well. In the current research, the results are not averaged (like in most meta-analysis research) but cumulated.

3.3. Vulnerabilities Ranking

- Binary rank—for vulnerabilities that exist or not (without middle levels), a binary scale is defined. The ranking range is if the vulnerability does not exist and if it exists. For example, for the vulnerability of accessing the local DNS cache data, if they are not accessible, the vulnerability ranks is , and if they are accessible, the vulnerability ranks is .

- Multi-level rank—in vulnerabilities that have some level of threats, a multi-level discrete scale is defined. The ranking range may vary between different vulnerabilities according to the possible scenarios, where a value is assigned if the vulnerability does not exist and values greater than are assigned if it exists (the greater the value, the greater the vulnerability level). For example, for the vulnerability of accessing task manager data, if accessing the data is not possible the vulnerability rank is , if only open sessions are disclosed the vulnerability rank is , and if the entire list is disclosed the vulnerability rank is .

3.4. List of Vulnerabilities

3.5. The Privacy Impact

4. The Empirical Study

4.1. Empirical Study Environment

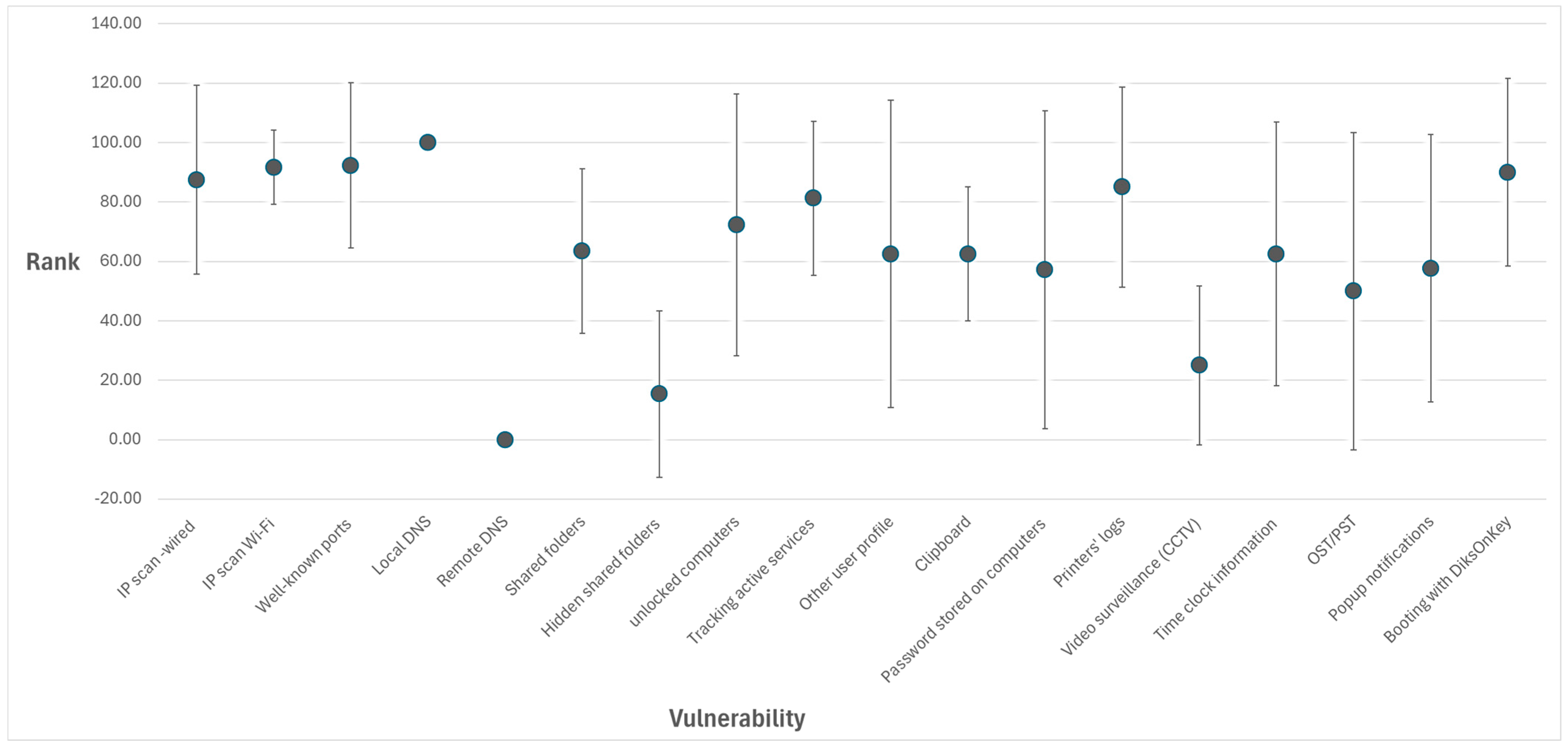

4.2. Results

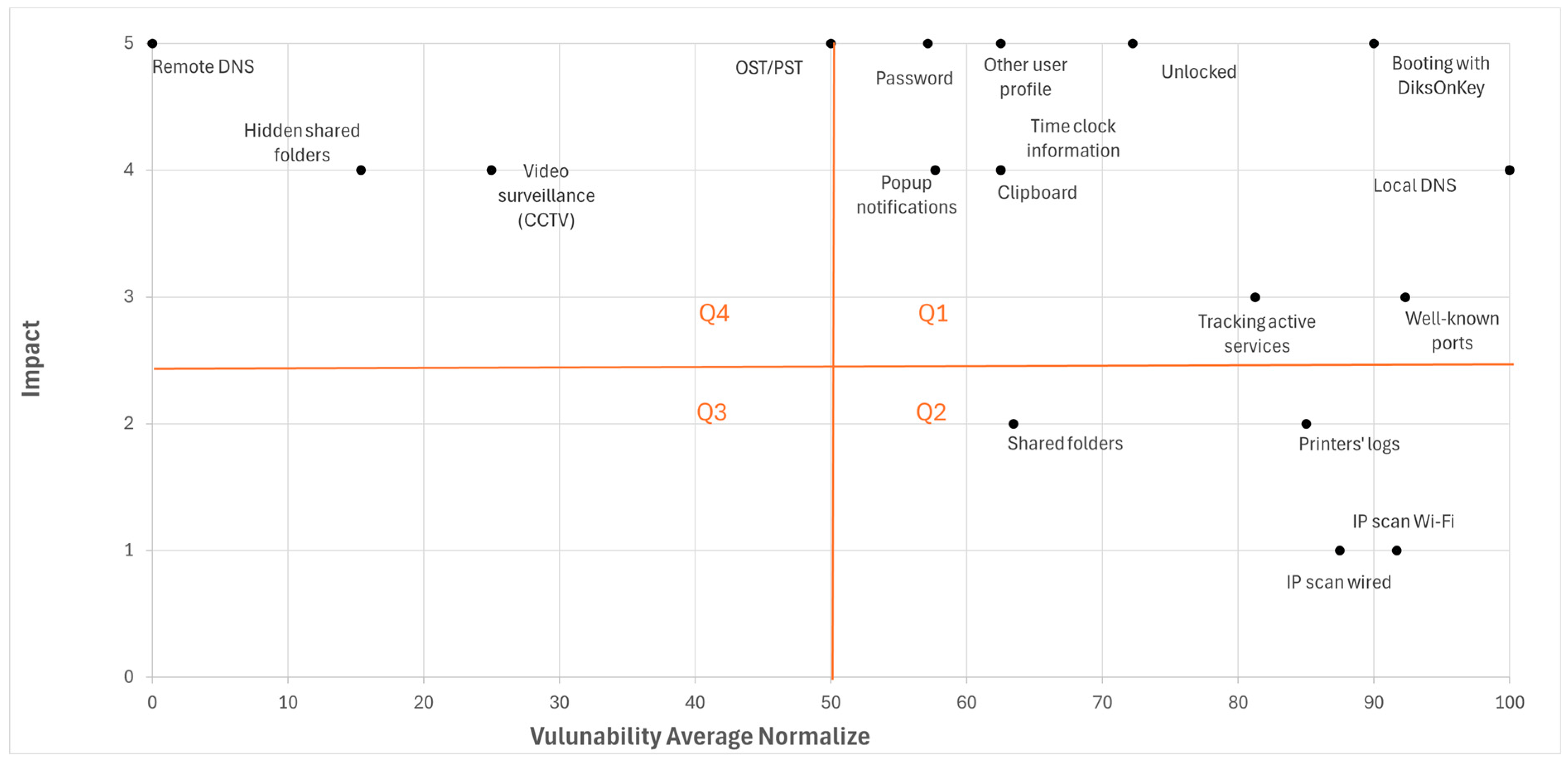

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jin, H.; Luo, Y.; Li, P.; Mathew, J. A review of secure and privacy-preserving medical data sharing. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 61656–61669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, L.; Yin, G.; Li, L.; Zhao, H. A survey on security and privacy issues in Internet-of-Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, X.; Desai, B.C. Data on the move and Issues of Privacy and security: Dangers of the web. In Proceedings of the 20th International Database Engineering & Applications Symposium, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–13 July 2016; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Preibusch, S. Guide to measuring privacy concern: Review of survey and observational instruments. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2013, 71, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD privacy Guidlines. 2013. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/digital/privacy/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Oechtering, T. Calculated Privacy: Tech Meets Law & Law Meets Tech. FIU Law Rev. 2023, 17, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, P.; Von dem Bussche, A. The eu General Data Protection Regulation (gdpr); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- University of South Florida. What is a Network. 2013. Available online: https://fcit.usf.edu/network/chap1/chap1.htm (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Sheng, O.R.L.; Lee, H. Data allocation design in computer networks: LAN versus MAN versus WAN. Ann. Oper. Res. 1992, 36, 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, G. Local Area Network. In Data Communications Networking Devices: Operation, Utilization and LAN and WAN Internetworking; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 269–345. [Google Scholar]

- David, J. LAN security standards. Comput. Secur. 1992, 11, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, W. Software-defined wide area networks (sd-wans): A survey. Electronics 2024, 13, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearley, A. IEEE 802.3 Ethernet Working Group. 2025. Available online: https://www.ieee802.org/3/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Stacey, R. Ieee802.11—Wireless Local Area Networks. 2025. Available online: https://www.ieee802.org/11/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Comer, D.E. Local Area Networks. In The Internet Book: Everything You Need to Know About Computer Networking and How the INTERNET Works, 5th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- AWS, What’s the Difference between LAN and WAN? 2024. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/compare/the-difference-between-lan-and-wan/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Held, G. Wide Area Network. In Data Communications Networking Devices: Operation, Utilization and LAN and WAN Internetworking; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 171–264. [Google Scholar]

- Comer, D.E. Internet: Motivatin And Beginnings. In The Internet book: Everything you need to know about computer networking and How the Internet Works, 5th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Graydon, M.; Parks, L. ‘Connecting the unconnected’: A critical assessment of US satellite Internet services. Media Cult. Soc. 2020, 42, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furini, M.; Mirri, S.; Montangero, M.; Prandi, C. Privacy perception when using smartphone applications. Mob. Networks Appl. 2020, 25, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghareeb, M.S.; Almaayah, M. Cyber Security Risk Management for Threats in Wireless LAN: A Literature Review. STAP J. Secur. Risk Manag. 2025, 2025, 22–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadimpalli, A.V.; Sai, A.S.; Kamalesh, M.D. Analyzing and exploiting Network Attacks and Defenses via Wireshark and Metasploit. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Communication Systems (ICKECS), Chickballapur, India, 23–24 April 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chenthara, S.; Ahmed, K.; Wang, H.; Whittaker, F. Security and privacy-preserving challenges of e-health solutions in cloud computing. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 74361–74382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schaik, P.; Jansen, J.; Onibokun, J.; Camp, J.; Kusev, P. Security and privacy in online social networking: Risk perceptions and precautionary behaviour. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zheng, T.; Jin, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tian, Z. A Strategy-Making Method for PIoT PLC Honeypoint Defense Against Attacks Based on the Time-Delay Evolutionary Game. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 11528–11543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Wang, H.J.; Hu, Y.-C. Preserving location privacy in wireless LANs. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications and Services, Association for Computing Machinery, San Juan, PR, USA, 11–14 June 2007; pp. 246–257. [Google Scholar]

- Gruteser, M.; Grunwald, D. Enhancing location privacy in wireless LAN through disposable interface identifiers: A quantitative analysis. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Workshop on Wireless Mobile Applications and Services on WLAN Hotspots, San Diego, CA, USA, 19 September 2003; pp. 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, N.; Wang, X.O.; Cheng, W.; Mohapatra, P.; Seneviratne, A. Characterizing privacy leakage of public wifi networks for users on travel. In Proceedings of the 2013 Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM, Turin, Italy, 14–19 April 2013; IEEE: Taipei, Taiwan, 2013; pp. 2769–2777. [Google Scholar]

- Klasnja, P.; Consolvo, S.; Jung, J.; Greenstein, B.M.; LeGrand, L.; Powledge, P.; Wetherall, D. “When I am on Wi-Fi, I am fearless” privacy concerns & practices in eeryday Wi-Fi use. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 26 April–1 May 2009; pp. 1993–2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, W.; Peng, D.; Liu, Y.; Liao, X.; Jiang, H. Adversarial WiFi sensing for privacy preservation of human behaviors. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2019, 24, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomaraswamy, G.; Kumar, S.P.; Marhic, M.E. Fiber-optic LAN/WAN systems to support confidential communication. Comput. Secur. 1991, 10, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Privacy, J.W. The Workplace and the Internet. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 28, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhave, D.P.; Teo, L.H.; Dalal, R.S. Privacy at work: A review and a research agenda for a contested terrain. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 127–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNall, L.A.; Stanton, J.M. Private eyes are watching you: Reactions to location sensing technologies. J. Bus. Psychol. 2011, 26, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivack, A.J.; Askay, D.A.; Rogelberg, S.G. Contemporary physical workspaces: A review of current research, trends, and implications for future environmental psychology inquiry. In Environmental Psychology: New Developments; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; De Dear, R. Workspace satisfaction: The privacy-communication trade-off in open-plan offices. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaodong, D.; Quan, W.; Pengfei, Y.; Haijing, Z.; Yuyan, H.; Haitao, W.; Zhongbin, P. Security system for internal network printing. In Proceedings of the 2012 Eighth International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Security, Guangzhou, China, 17–18 November 2012; IEEE: Taipei, Taiwan, 2013; pp. 596–600. [Google Scholar]

- Tymchenko, O.; Havrysh, B.; Khamula, O.; Lysenko, S.; Havrysh, K. Risks of Loss of Personal Data in the Process of Sending and Printing Documents. In CITRisk; CEUR-WS.org: Kherson, Ukraine, 2020; pp. 373–384. [Google Scholar]

- Lukusa, J. A security model for mitigating multifunction network printers vulnerabilities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Internet, Cyber Security and Information Systems, Gaborone, Botswana, 18–20 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z. Breaking BLE MAC Address Randomization with Allowlist-Based Side Channels and its Countermeasure. ACM Trans. Priv. Secur. 2025, 28, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, W.; Ding, Z. Detecting malicious DoH traffic: Leveraging small sample analysis and adversarial networks for detection. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2024, 84, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AWS What is DNS? 2024. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/route53/what-is-dns/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Van Der Toorn, O.; Müller, M.; Dickinson, S.; Hesselman, C.; Sperotto, A.; van Rijswijk-Deij, R. Addressing the challenges of modern DNS a comprehensive tutorial. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2022, 45, 100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klei, A. Cross layer attacks and how to use them (for DNS cache poisoning, device tracking and more. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, San Francisco, CA, USA, 23–27 May 2021; IEEE: Taipei, Taiwan, 2021; pp. 1179–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Vitalii, T.; Anna, B.; Kateryna, H.; Hrebeniuk, D. Method of building dynamic multi-hop VPN chains for ensuring security of terminal access systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Problems of Infocommunications. Science and Technology (PIC S&T), Kharkiv, Ukraine, 6–9 October 2020; IEEE: Taipei, Taiwan, 2020; pp. 613–618. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P. Security and privacy protection in cloud computing: Discussions and challenges. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2020, 160, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipner, S.; Howard, M. Inside the Windows Security Push: A Twenty-Year Retrospective. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2023, 21, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.; Hassell, J. Storage Management. In Outlook 2007: Beyond the Manual; Apress: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Reddit, Why Is It Not “Best Practice” to Have OSTs on a Terminal Server? 2014. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/sysadmin/comments/20bgcw/comment/cg22m01/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Domingues, P.; Andrade, L.; Frade, M. A Digital Forensic View of Windows 10 Notifications. Forensic Sci. 2022, 2, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, S.A.K.A.; Nirwan, R.; Bhowmik, C.; Jain, N.A.O. Biometric Based Attendance System with Machine Learning Integrated Face Modelling and Recognition. In Advancement of Intelligent Computational Methods and Technologies; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Liu, J.; Dong, T.; Pei, Q.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y. Eyes see hazy while algorithms recognize who you are. ACM Trans. Priv. Secur. 2024, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.; Tham, T.L. Workplace biometrics: Protecting employee privacy one fingerprint at a time. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2020, 43, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahu, E.; Wache, H.; Piangerelli, M. Secure and Decentralized Hybrid Multi-Face Recognition for IoT Applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenvica, How to Connect an ZKTeco Device to Software. 2022. Available online: https://lenvica.com/how-to-connect-an-zkteco-time-attendance-device-to-attendhrm/#alphanumeric (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Farik, M.; Ali, A. Analysis of default passwords in routers against brute-force attack. Int. J. Technol. Enhanc. Emerg. Eng. Res. 2015, 4, 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- Paneda, X.G.; Melendi, D.; Corcoba, V.; Panda, A.G.; Garcia, R.; Garcia, D. Forensic Analysis of File Exfiltrations Using AnyDesk, TeamViewer and Chrome Remote Desktop. Electronics 2024, 13, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-Uson, J.A.M.E.; Morat’o, D.; Izal, M. Protocol-agnostic method for monitoring interactivity time in remote desktop services. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 19107–19135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; You, J.; Xu, T. Risk Analysis of Digital Twin Project Operation Based on Improved FMEA Method. Systems 2025, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Kim, H.; Kang, C. Efficiency Analysis of the Integrated Application of Hazard Operability (HAZOP) and Job Safety Analysis (JSA) Compared to HAZOP Alone for Preventing Fire and Explosions in Chemical Plants. Processes 2025, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, R.; Chakhchoukh, Y.; Johnson, B.; Le Blanc, K.; Smidts, C. A Modular Dynamic Probabilistic Risk Assessment Framework for Electric Grid Cybersecurity. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obono, O.; Tawo, B.P. mproving security in a virtual local area network. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2022, 100, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Anjum, I.; Sokal, J.; Rehman, H.R.; Weintraub, B.; Leba, E.; Enck, W.; Nita-Rotaru, C.; Reaves, B. MSNetViews: Geographically distributed management of enterprise network security policy. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM Symposium on Access Control Models and Technologies, Trento, Italy, 7–9 June 2023; pp. 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Harkin, D.; Panagiotopoulos, V. Regulating Tools for Hacking: Limitations, Challenges and Possibilities. Policy Internet 2025, 17, 700004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, D.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H. A survey: When moving target defense meets game theory. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2023, 48, 10054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Sulaiman, R.B. Cyber Risk Management in the Internet of Things: Frameworks, Models, and Best Practices. STAP J. Secur. Risk Manag. 2024, 1, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odella, F. Privacy Awareness and the Networking Generation. In Censorship, Surveillance, and Privacy: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 1309–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Vold, K.; Whittlestone, J. Privacy, Autonomy, and Personalised Targeting: Rethinking How Personal Data is Used. In Report on Data, Privacy, and the Individual in the Digital Age; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, T.; Daniel, J.S. Nothing to Hide: The False Tradeoff between Privacy and Security; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2011; Volume 46. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K.; Ross, A.; Pankanti, S. Biometrics: A tool for information security. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2006, 2, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onumadu, P.; Abroshan, H. Near-Field Communication (NFC) Cyber Threats and Mitigation Solutions in Payment Transactions: A Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, F.; Gatzert, N.; Gruner, P. Cyber risk management in SMEs: Insights from industry surveys. J. Risk Financ. 2021, 22, 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vulnerability | Explanation | Privacy Implications | Ranking Range | Materialization Access Platform | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IP scan over a wired network | A simple scan of the LAN using an available utility can reveal devices that are currently connected. The information may include the IP address, computer name, device type, MAC address, and device status. Scanning the subnet mask can reveal devices currently connected to other VLANs. | It is possible to deduce if a user is connected and available. In other words, if an individual is absent or is working. | {0, 1, 2, 3, 4} 0 no threat 1 only the IP address is revealed 2 IP address and device name are revealed 3 the entire host’s details are revealed 4 hosts from other VLANs are also revealed | Any host in the LAN |

| 2 | IP scan over Wi-Fi | A simple scan of the Wi-Fi network using an available utility can reveal currently connected devices, including private devices such as smartphones and notebooks. The information may include IP address, computer name, device type, MAC address, and device status. | It is possible to deduce if a user is connected and available. If MAC randomization is applied, the user can still be tracked within a specific network, but the information cannot be crossed between networks. Moreover, in a wide area Wi-Fi network that includes access points, the location of the user may be disclosed. | {0, 1, 2, 3, 4} 0 no threat 1 only IP address is exposed 2 IP address and device name are exposed 3 the entire host’s details are exposed 4 hosts from other VLANs are also exposed | Any host in the LAN |

| 3 | Well-known ports | By mapping the open ports on the LAN, it is possible to identify which applications and services are active on a specific device. | It is possible to disclose activities that the user is conducting, e.g., file sharing, remote access, and printing. (Moreover, knowing the open ports may be useful to carry out cyber-attacks that may compromise privacy; but this does not fall within the inclusion criteria of this research). | {0, 1} 0 no threat 1 threat exists | Any host in the LAN |

| 4 | Local DNS data | By accessing the local DNS data, it is possible to intercept DNS request contact. This attack can be launched only from the specific PC. | When a user is browsing the Internet, the DNS requests may be of interest to another user who has access to this computer, thus disclosing the first user’s browsing history. | {0, 1} 0 no threat 1 threat exists | The local host |

| 5 | Remote DNS data | By accessing the DNS server data, namely the DC DNS or the router DNS, it is possible to intercept DNS request contact. This attack can be launched in all the LANs. | When all the users browse the Internet, the DNS requests may be of interest to another user who connects to the same LAN, thus disclosing all the users’ browsing history on this LAN. | {0, 1} 0 no threat 1 threat exists | Any host in the LAN |

| 6 | Shared folders | By using a network discovery tool (which is publicly available even as a built-in Windows feature), it is possible to discover all the devices on the LAN with open share folders. The user actively initiates the sharing (the information includes the computers’ names and sharing names). Thus, unless permissions are limited, there is access to these folders’ content. | It is possible to access shared files which may contain sensitive data. | {0, 1, 2, 3, 4} 0 no threat 1 list of folders and/or files is enabled 2 folder and files read (open files) is enabled. 3 folder and files write/edit is enabled. 4 the user is granted full control permission | Any host in the LAN |

| 7 | Hidden shared folders | Accessing Microsoft default hidden shared folders that were created by the operating system as part of the system architecture (e.g., \C$, \ADMIN$, \IPC$) enables the user to access these folders’ content and even content on the entire disk. | Sensitive data on shared folders or even on the entire disk may be disclosed. | {0, 1, 2, 3, 4} 0 no threat 1 list of folders and/or files is enabled 2 folder and files read (open files) is enabled. 3 folder and files write/edit is enabled. 4 the user is granted full control | Any host in the LAN |

| 8 | Unlocked computers | When a computer is not locked, other users have access, at times by only a slight move of the mouse (in many cases, users rely on the auto-lock mechanism, in which case, until the auto-lock activates vulnerability exists). | It is possible to access all the data that the last user had permission to access. | {0, 1, 2} 0 no threat 1 the screen is black, but the computer is not password protected when the mouse is slightly moved 2 the screen is on. | The local host |

| 9 | Tracking active users’ Windows services | Opening the Task Manager on a local PC or a terminal server allows all of the applications and services currently running on the PC to be viewed (even those used by other users). | The list of all applications and services that currently run (used) can be disclosed. | {0, 1, 2} 0 no threat 1 only the open session is disclosed 2 the entire list is disclosed | The local host |

| 10 | Other user’s profile | Opening the user’s folder on a local disk displays the list of all users that are logged on to the PC. Opening the user’s folder enables access to all the user’s profiles. | The user profile includes Desktop, My Documents, pictures and more. | {0, 1} 0 no threat 1 threat exists | The local host |

| 11 | Clipboard | By pasting from the clipboard, the last object copied can be disclosed. If the Windows clipboard history is enabled, a list of the last copied objects can be disclosed. The clipboard may preserve its contents even after the user is changed. | The clipboard can contain sensitive text, pictures, passwords, and other objects. | {0, 1, 2} 0 no threat 1 clipboard data is available if the user is still logged on 2 clipboard data is available even after the user is changed | The local host |

| 12 | Password stored on shared workstations computers | Accessing the password manager on Google Chrome or Microsoft Edge discloses all the passwords stored in the profile (other third-party software may also be vulnerable). | Sensitive information, for example, on private sections of websites, can be disclosed. | {0, 1} 0 no threat 1 threat exists | The local host |

| 13 | Printer log | By browsing the printer IP address, it is possible to access the printer management portal and view the print job log. | The log may contain sensitive data such as the name of the user and names of files that were printed. | {0, 1, 2} 0 no threat 1 the default password enables access 2 no password is needed | Any host in the LAN |

| 14 | Video surveillance (CCTV) | A LAN mapping can discover NVR/DVR devices that are currently connected, and the video stream and even the recording may be accessed by means of the default password. | Live broadcasts and recordings may contain sensitive data. | {0, 1, 2} 0 no threat 1 the default password enables access 2 no password is needed | Any host in the LAN |

| 15 | Time clock information | A LAN mapping can expose the time clock that is currently connected, and by using a free utility that can be downloaded from the manufacturer’s website, it is possible to access the clock’s database. | The time clock contains sensitive data about the present and past workers. | {0, 1, 2} 0 no threat 1 the default password enables access 2 no password is needed | Any host in the LAN |

| 16 | OST/PST (Microsoft outlook data files) | Searching for OST or PST file extensions on the local disk or on shared folders can disclose other users’ email data. | Personal email data may contain sensitive data, including email contacts, address book, and attached files. | {0, 1} 0 no threat 1 threat exists | The local host |

| 17 | Popup notifications when screen locked | When the computer is locked notifications can still pop up on the screen. | Personal data such as massages can be disclosed. | {0, 1, 2} 0 no threat 1 only title is disclosed 2 the entire message is exposed | The local host |

| 18 | Booting the computer with an external source | Booting the computer from an external source such as a DiskOnKey or a CD, can disclose the entire data that is stored on the hard disk (unless encrypted). | The hard disk may contain sensitive data. | {0, 1, 2} 0 no threat 1 it is possible to boot from an external source, but additional actions are required (e.g., driver installation) 2 it is possible to boot from an external source without any additional requirements | The local host |

| Organization Number | Organization’s LAN | Organization Type | LAN Environment Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | Educational institution | A lecturer’s computer is installed in the classroom and students’ computers are installed in the Lab classes. All of these computers are connected to a domain. Logging into a computer is via a local profile. |

| A | 2 | Educational institution | There is free Wi-Fi throughout the campus. |

| B | 1 | Nuclear Pharmacy | Workstations are shared between users of the organization’s QC (Quality Control) stations and the production station. Every user connects to their own AD (Active Directory—Microsoft’s proprietary directory service that enables management pf permissions and access to network resources). All workstations have more than one user profile and are connected by a wired LAN. |

| B | 2 | Nuclear Pharmacy | Workstations are installed in the product and QC areas. Some of the workstations’ login process is personal, while others are based on generic user names. |

| B | 3 | Nuclear Pharmacy | There are Wi-Fi access points with visible SSIDs (Service Set Identifier—the name of the Wi-Fi network) and passwords throughout the factory. |

| C | Factory | There is a DC (Domain Controller—a server that is responsible for managing the network and identity security requests) server with shared folders and two ERP servers (two different software). All of the workstations are connected to an AD, and the users access the ERP application by means of personal user accounts. | |

| D | Hotel chain | Servers are hosted in Google farm. The DC, application servers, and four Terminal servers share the same LAN with a roaming profile (the user profile is stored on a shared folder and by applying roaming, this information is shared on the four servers). Each Hotel is connected to the servers by a site2site VPN, where most stations are part of the domain. Some users have personal accounts, others like house-keeping and reception use functional accounts. | |

| E | Factory | A local network with a DC, ERP server, and a Terminal server. All users are connected through a local Workstation to an AD and run a Terminal server client from the desktop. Only the engineering department works locally with a CAD (Computer Aided Design) software. | |

| F | International trade agency (import and export) | A local network with a shared NAS and P2P architecture. Each user has their own profile, while some of the PCs contain profiles of more than one user. Some users have a profile on more than one PC. | |

| G | Mechanical equipment trading (wholesale and retail) | There is a site2site connection between the head office and two branch offices. DC and ERP are available for all users, where remote users are connected via the terminal server and head office users are connected via a LAN. | |

| H | Home environment | Home LAN with a few workstations (each with its own profile), laptops (belonging to the homeowner’s workplace), cell phones, a network printer, and IoT cameras. | |

| I | Public Wi-Fi in a coffee shop | A coffee shop with free Wi-Fi, accessible by customers with laptops and cell phones. | |

| J | Educational institution | A LAN that includes classroom PCs in an academic campus, which are mainly used for presentations. The computers are connected by wire, have a free shared profile, and have no domain definitions. |

| Vulnerability | Ranking Range | LAN Environment | Normalized Average per Vulnerability | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2 | B1 | B2 | B3 | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | |||

| IP scan-wired | {0, 1, 2, 3, 4} | 100 (4) | N/A | 100 (4) | 0 (0) | N/A | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 75 (3) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | N/A | 100 (4) | 88% |

| IP scan Wi-Fi | {0, 1, 2, 3, 4} | N/A | 100 (4) | N/A | N/A | 75 (3) | 100 (4) | 75 (3) | 75 (3) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | N/A | 92% |

| Well-known ports | {0, 1} | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 92% |

| Local DNS | {0, 1} | 100 (1) | N/A | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | N/A | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | N/A | 100 (1) | 100% |

| Remote DNS | {0,1} | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0% |

| Shared folders | {0, 1, 2, 3, 4} | 75 (3) | 100 (4) | 25 (1) | 0 (0) | 50 (2) | 75 (3) | 75 (3) | 75 (3) | 75 (3) | 75 (3) | 75 (3) | 50 (2) | 50 (2) | 63% |

| Hidden shared folders | {0, 1, 2, 3, 4} | 25 (1) | 25 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 (1) | 100 (4) | 25 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 15% |

| Unlocked computers | {0, 1, 2} | 100 (2) | N/A | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 50 (1) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | N/A | N/A | 72% |

| Tracking active services | {0, 1, 2} | 100 (2) | N/A | 100 (2) | 50 (1) | N/A | N/A | 50 (1) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 50 (1) | N/A | N/A | 100 (2) | 81% |

| Other user profiles | {0, 1} | 0 (0) | N/A | 100 (1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 (0) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 100 (1) | N/A | 100 (1) | 63% |

| Clipboard | {0, 1, 2} | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 100 (2) | 50 (1) | 100 (2) | N/A | 100 (2) | 63% |

| Password stored on computers | {0, 1} | N/A | N/A | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | N/A | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | N/A | 100 (1) | 85% |

| Printers’ logs | {0, 1, 2} | 0 (0) | N/A | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 50 (1) | N/A | N/A | 85% |

| Video surveillance (CCTV) | {0, 1, 2} | N/A | N/A | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 50 (1) | 0 (0) | 50 (1) | N/A | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | N/A | N/A | 25% |

| Time clock information | {0,1,2} | N/A | N/A | 50 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 (2) | 50 (1) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 63% |

| OST/PST | {0, 1} | N/A | N/A | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 50% |

| Popup notifications | {0, 1, 2} | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 (2) | 0 (0) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 0 (0) | 58% |

| Booting with DiskOnKey | {0, 1, 2} | 100 (2) | N/A | 100 (2) | 0 (0) | N/A | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | N/A | 100 (2) | 90% |

| Average per LAN | 54% | 53% | 61% | 19% | 44% | 79% | 67% | 68% | 93% | 67% | 75% | 50% | 68% | 62% | |

| Vulnerability | Min Value | Max Value | Average | Standard Deviation | Number of N/A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP scan over wired network. | 0 | 100 | 87.5 | 31.73 | 3 |

| IP scan over Wi-Fi | 75 | 100 | 91.67 | 12.50 | 4 |

| Well-known ports | 0 | 100 | 92.31 | 27.74 | 0 |

| Local DNS data | 100 | 100 | 100.00 | 0 | 3 |

| Remote DNS data | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shared folders | 0 | 100 | 63.46 | 27.74 | 0 |

| Hidden shared folders | 0 | 100 | 15.38 | 28.02 | 0 |

| Unlocked computers | 0 | 100 | 72.22 | 44.10 | 4 |

| Tracking active users’ Windows services | 50 | 100 | 81.25 | 25.88 | 5 |

| Other user profiles | 0 | 100 | 62.50 | 51.75 | 5 |

| Clipboard | 50 | 100 | 62.50 | 22.61 | 1 |

| Password stored on shared computers | 0 | 100 | 57.14 | 53.45 | 6 |

| Printers’ logs | 0 | 100 | 85.00 | 33.75 | 3 |

| Video surveillance (CCTV) | 0 | 50 | 25.00 | 26.73 | 5 |

| Time clock information | 0 | 100 | 62.50 | 44.32 | 5 |

| OST/PST (Microsoft Outlook data files) | 0 | 100 | 50.00 | 53.45 | 5 |

| Popup notifications when screen locked | 0 | 100 | 57.69 | 44.94 | 0 |

| Booting the computer with DiskOnKey | 0 | 100 | 90.00 | 31.62 | 3 |

| Vulnerability | Normalized Average Vulnerability (%) | Impact Level | Impact Level Explanation | Average Overall Risk (0–5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP scan over wired network | 87.50 | 1 | The information is limited to the computer’s IP address and name only. | 0.88 |

| IP scan over Wi-Fi | 91.67 | 1 | The information is limited to the computer’s IP address and name only. | 0.92 |

| Well-known ports | 92.31 | 3 | Software that are used by the user may be exposed, but not the content. | 2.77 |

| Local DNS data | 100.00 | 4 | Browsing history of the local computer may be exposed. | 4.00 |

| Remote DNS data | 0 | 5 | Browing history of the entire LAN may be exposed. | 0 |

| Shared folders | 63.48 | 2 | Shared data, which is usually not private, may be exposed. | 1.27 |

| Hidden shared folders | 15.38 | 4 | Shared data, which might be private, may be exposed. | 0.61 |

| Unlocked computers | 72.22 | 5 | Access to an unlocked computer may compromise all users’ data. | 3.61 |

| Tracking active users’ Windows services | 81.25 | 3 | Services and software that are used on the PC may be exposed, but not their content. | 2.44 |

| Other user profiles | 62.50 | 5 | All users’ profiles, including the users’ documents, may be exposed. | 3.13 |

| Clipboard | 62.50 | 4 | The clipboard history of other users that used the same PC may be exposed. | 2.50 |

| Password stored on shared workstations computers | 57.14 | 5 | Users’ passwords may be compromised. | 2.86 |

| Printers’ logs | 85.00 | 2 | Printers’ job history may be exposed, but not the printed content. | 1.70 |

| Video surveillance (CCTV) | 25.00 | 4 | Videos of the environment (live or recordings) may be exposed. | 1 |

| Time clock information | 62.50 | 4 | Attendance of employees may be exposed. | 2.50 |

| OST/PST (Microsoft outlook data files) | 50.00 | 5 | The outlook database which includes emails, calendar, contacts, etc., may be disclosed. | 2.50 |

| Popup notifications when screen locked | 57.69 | 4 | Visible popup notification messages may be exposed to all users. | 2.31 |

| Booting the computer with DiskOnKey | 90.00 | 5 | All the disk content may be disclosed. | 4.50 |

| Vulnerability | Technological Tools (Actions that Are Not Taken by the User) | Awareness and Behavioral (Actions that Are Taken by the User) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IP scan over a wired network. | Block the ICMP protocol, and use an IDS system to detect scanning on the LAN. | - |

| 2 | IP scan over Wi-Fi | Block the ICMP protocol, and use an IDS system to detect scanning on the LAN. | - |

| 3 | Well-known ports | Use an IDS system that detects port scanning over the LAN. | |

| 4 | Local DNS data | Clear local flush DNS on every login. | |

| 5 | Remote DNS data | DNS security hardening. | |

| 6 | Shared folders | Scanning the LAN for insecure shared. | Do not open a shared folder with weak permissions. |

| 7 | Hidden shared folders | A software agent that ensures that no user possesses privileges exceeding the self-operational needs. | |

| 8 | Unlocked computers | Enforce the group policy of the lock screen on unused PCs | Lock your screen when you leave your workplace. |

| 9 | Tracking active users’ Windows services | Ensuring that no users possess privileges exceeding their operational needs. | |

| 10 | Other user’s profile | A utility that checks that users do not have local administrator privileges. | |

| 11 | Clipboard | Create a script that cleans the clipboard on logout. | Keep the clipboard clean when leaving the workstation. |

| 12 | Password stored on shared workstations computers | Disable the ‘Save Password’ option on shared workstations. | Do not save passwords on shared workstations. |

| 13 | Printer log | If the log printer access is not public, the default password must be changed. | |

| 14 | Video surveillance (CCTV) | Video system default password must be changed. The CCTV system should be on a separate VLAN with a limited access. | |

| 15 | Time clock information | Time clock default password must be changed. Time clock system should be on a separate VLAN with limited access. | |

| 16 | OST/PST (Microsoft outlook data files) | Use encrypted OST/PST file. Keep files on home directory with limited access | |

| 17 | Popup notifications when screen locked | Keep the system updated. | Close application when leaving the workplace. |

| 18 | Booting the computer with an external source | Encrypt the disk. Disable access to the PC. Use a BIOS password. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fine, Z.; Hirschprung, R.S. Mapping Privacy Vulnerabilities in Local Area Network (LAN) Environments. Sensors 2026, 26, 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030763

Fine Z, Hirschprung RS. Mapping Privacy Vulnerabilities in Local Area Network (LAN) Environments. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):763. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030763

Chicago/Turabian StyleFine, Zohar, and Ron S. Hirschprung. 2026. "Mapping Privacy Vulnerabilities in Local Area Network (LAN) Environments" Sensors 26, no. 3: 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030763

APA StyleFine, Z., & Hirschprung, R. S. (2026). Mapping Privacy Vulnerabilities in Local Area Network (LAN) Environments. Sensors, 26(3), 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030763