Acoustic Emission Analysis of Moisture Damage Mechanisms in 3D Printed Auxetic Core Sandwiches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experimental Processes

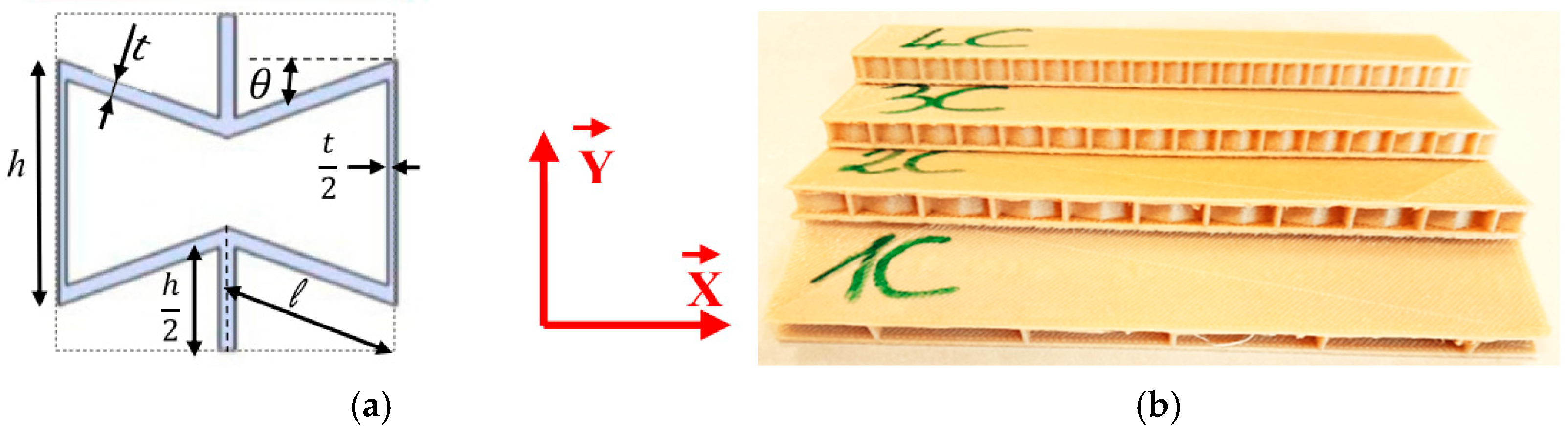

2.1. Materials and Manufacturing

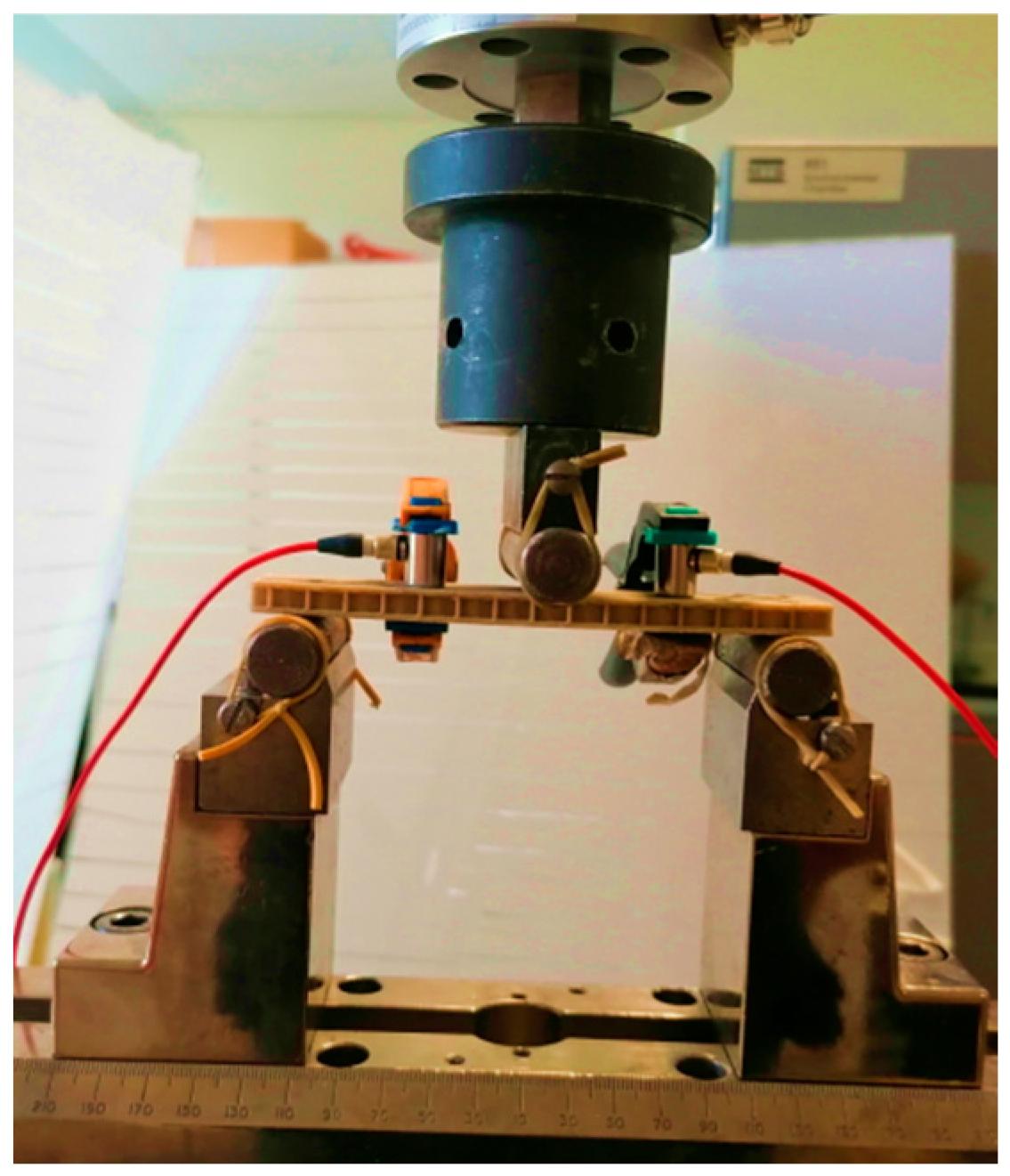

2.2. Mechanical Tests

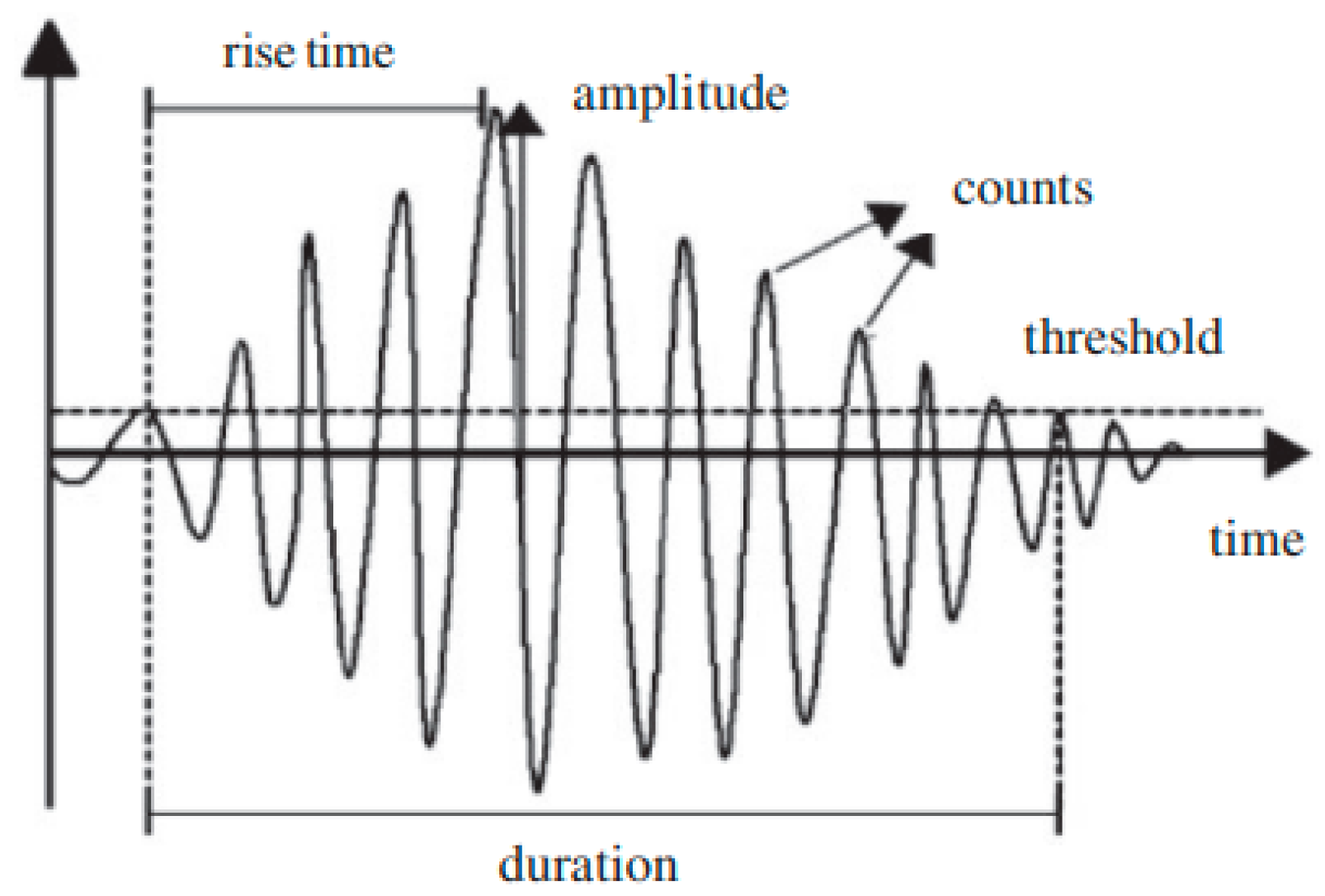

2.3. Acoustic Emission Technique

- -

- The PDT (peak definition time) determines the rise time of the acoustic event. PDT = 50 ms.

- -

- The HDT (Hit Definition Time) determines the end of the acoustic event. HDT = 100 ms.

- -

- The HLT (Hit Lock-out Time) creates a dead time at the end of each acoustic event in order to exclude late reflections. HLT = 200 ms.

2.4. Aging Conditions

3. Results and Discussion

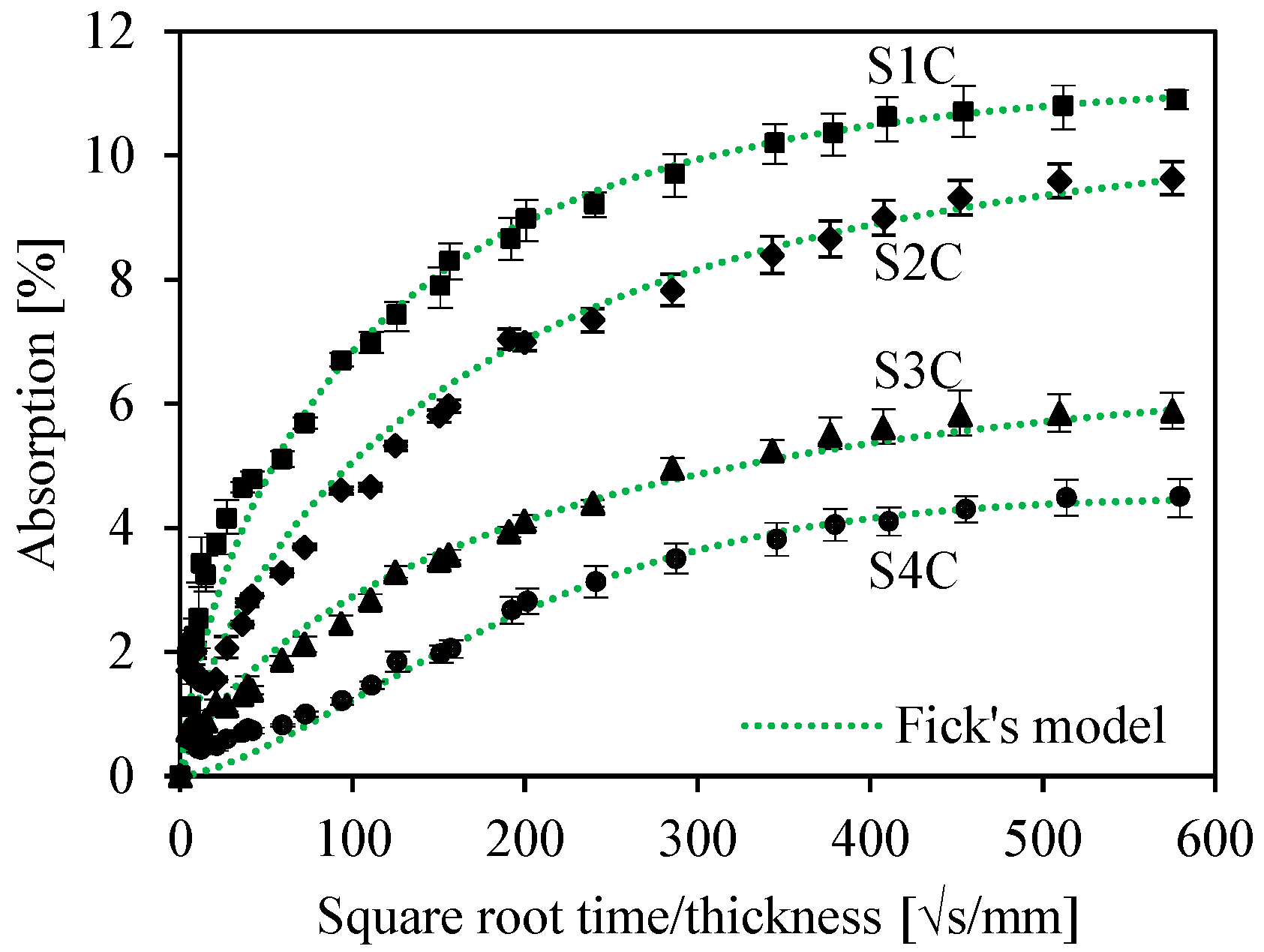

3.1. Water Absorption of Sandwich Composites

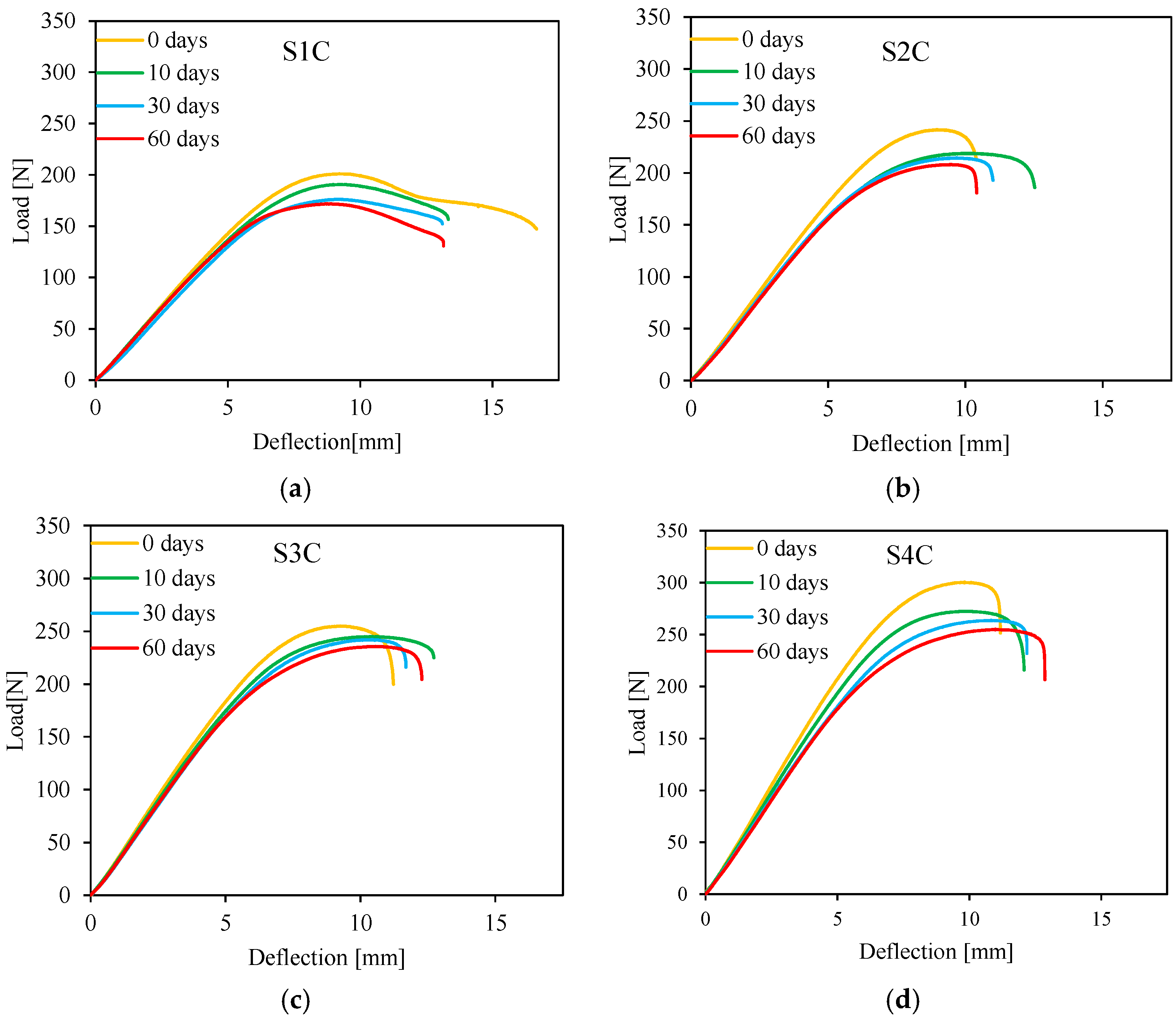

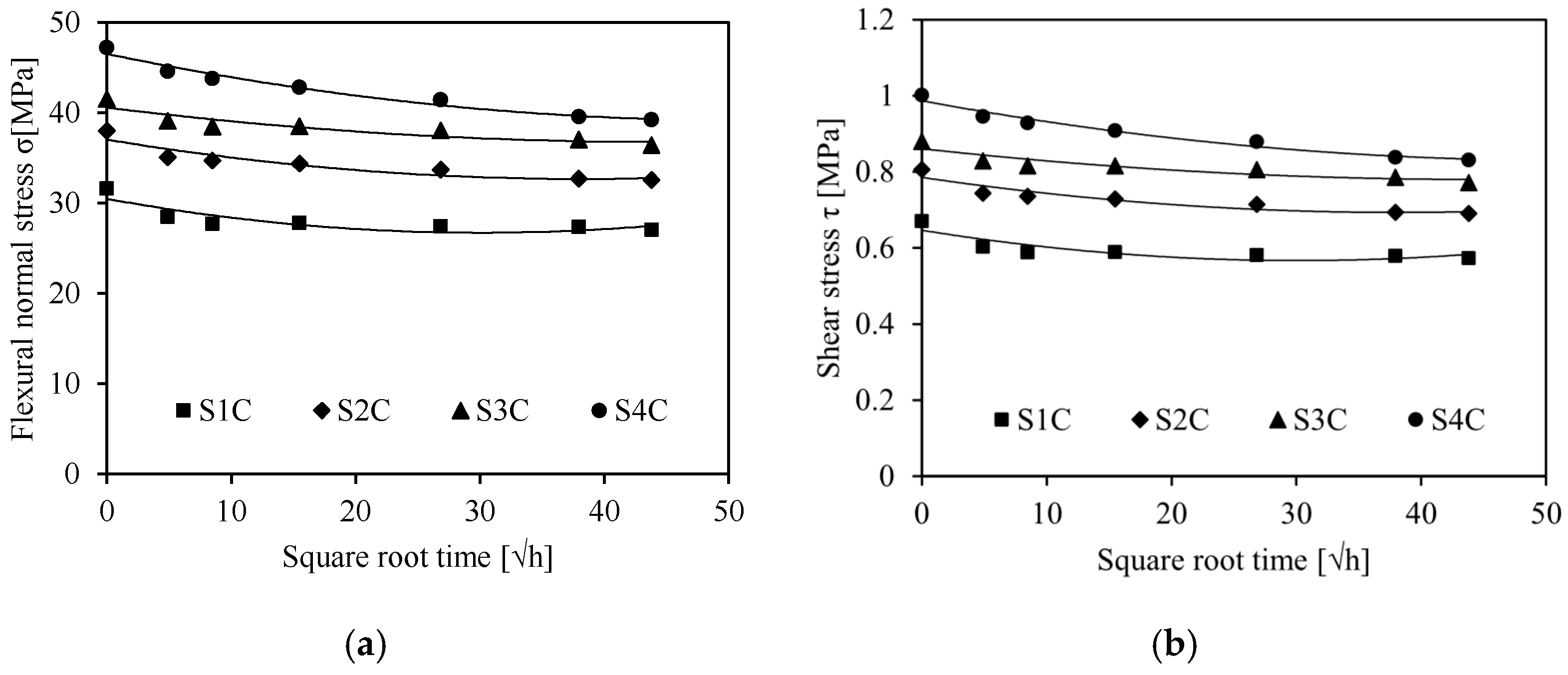

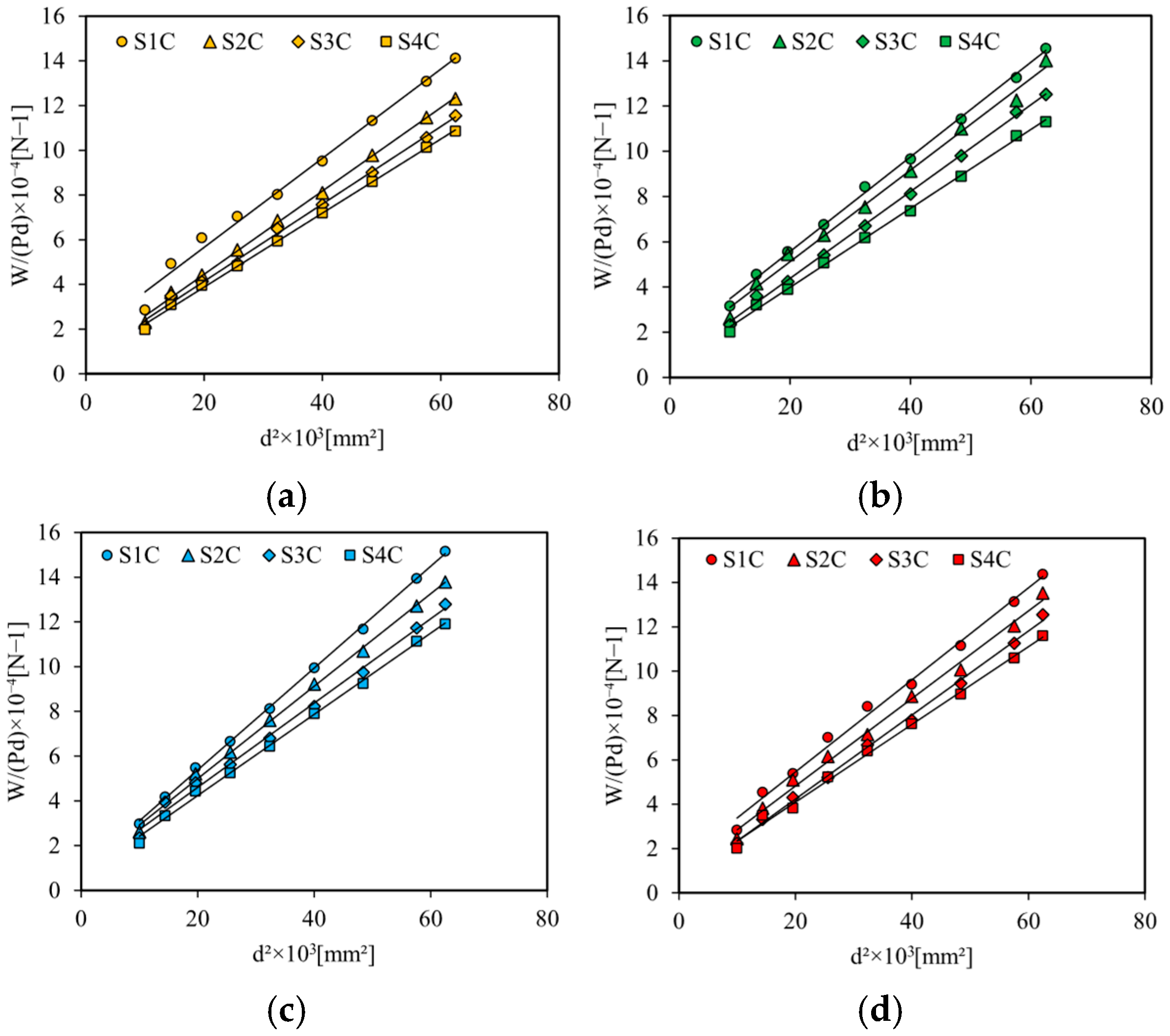

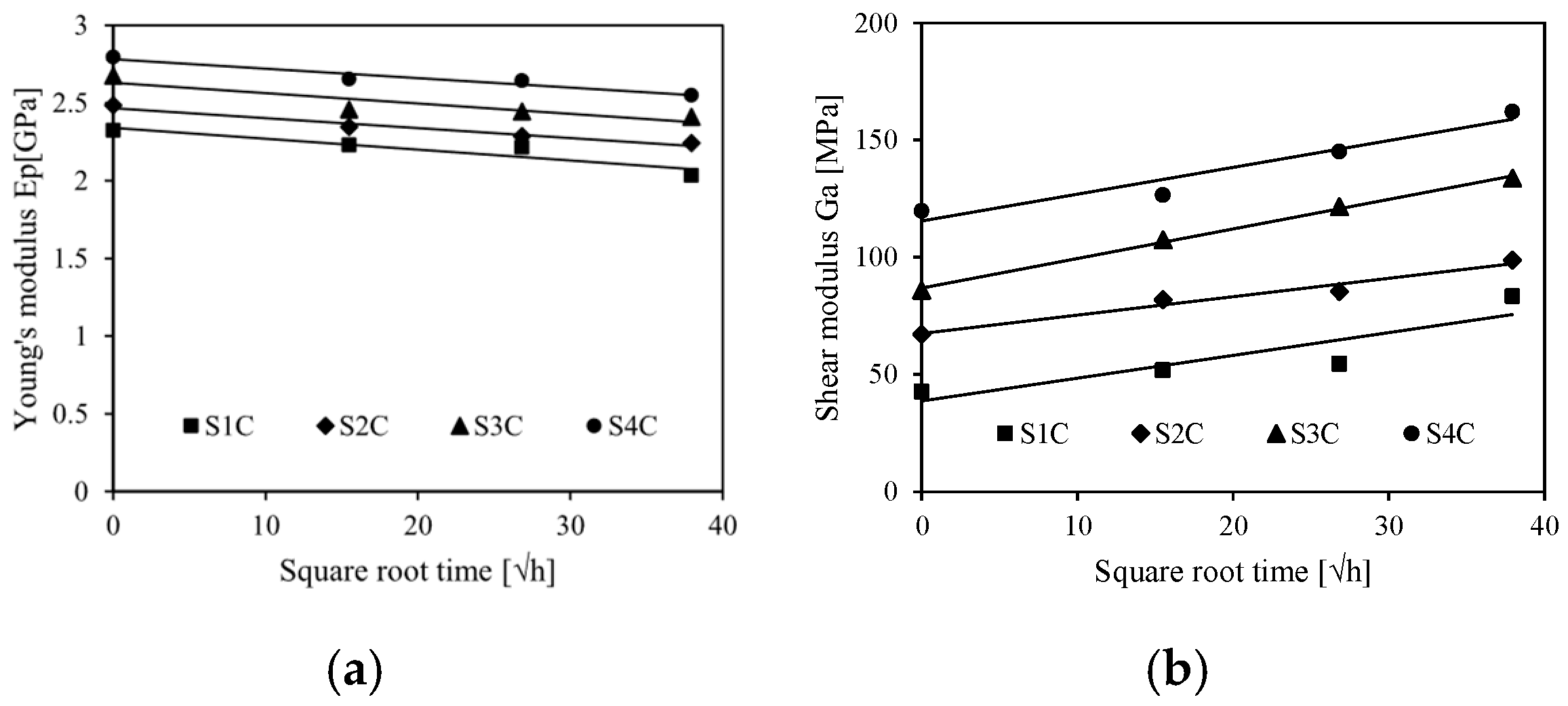

3.2. Effect of Water Absorption on the Static Behavior

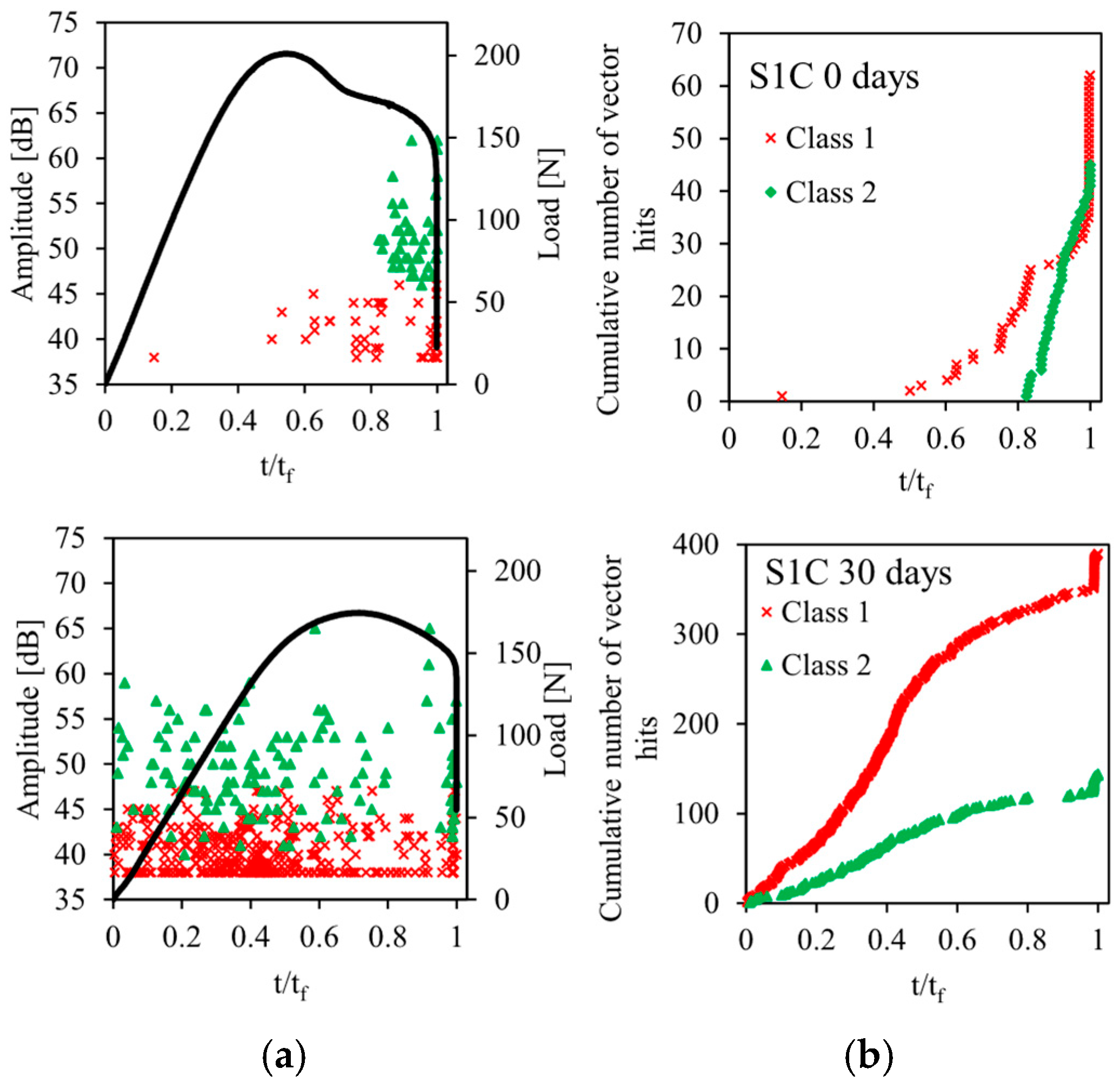

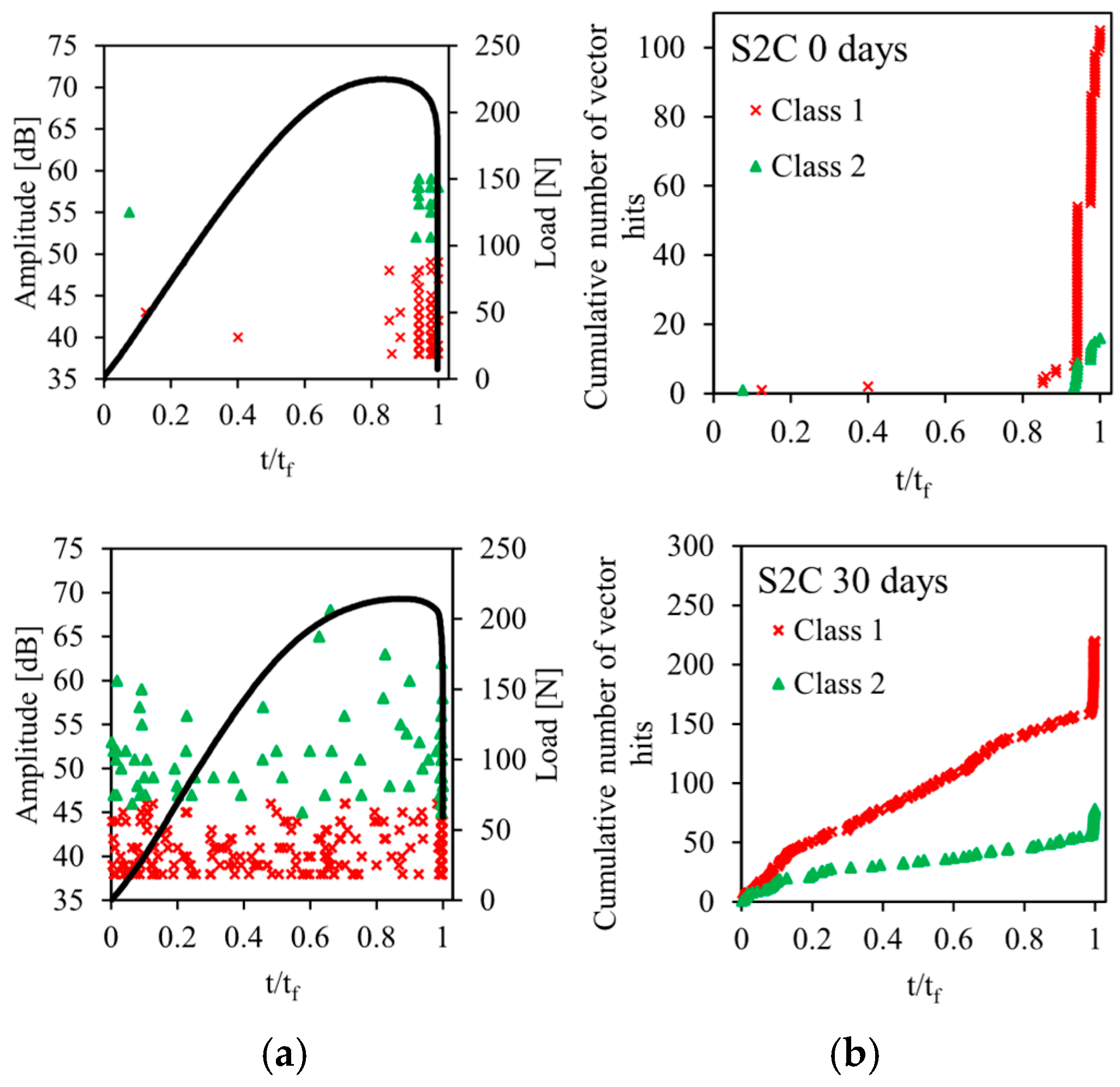

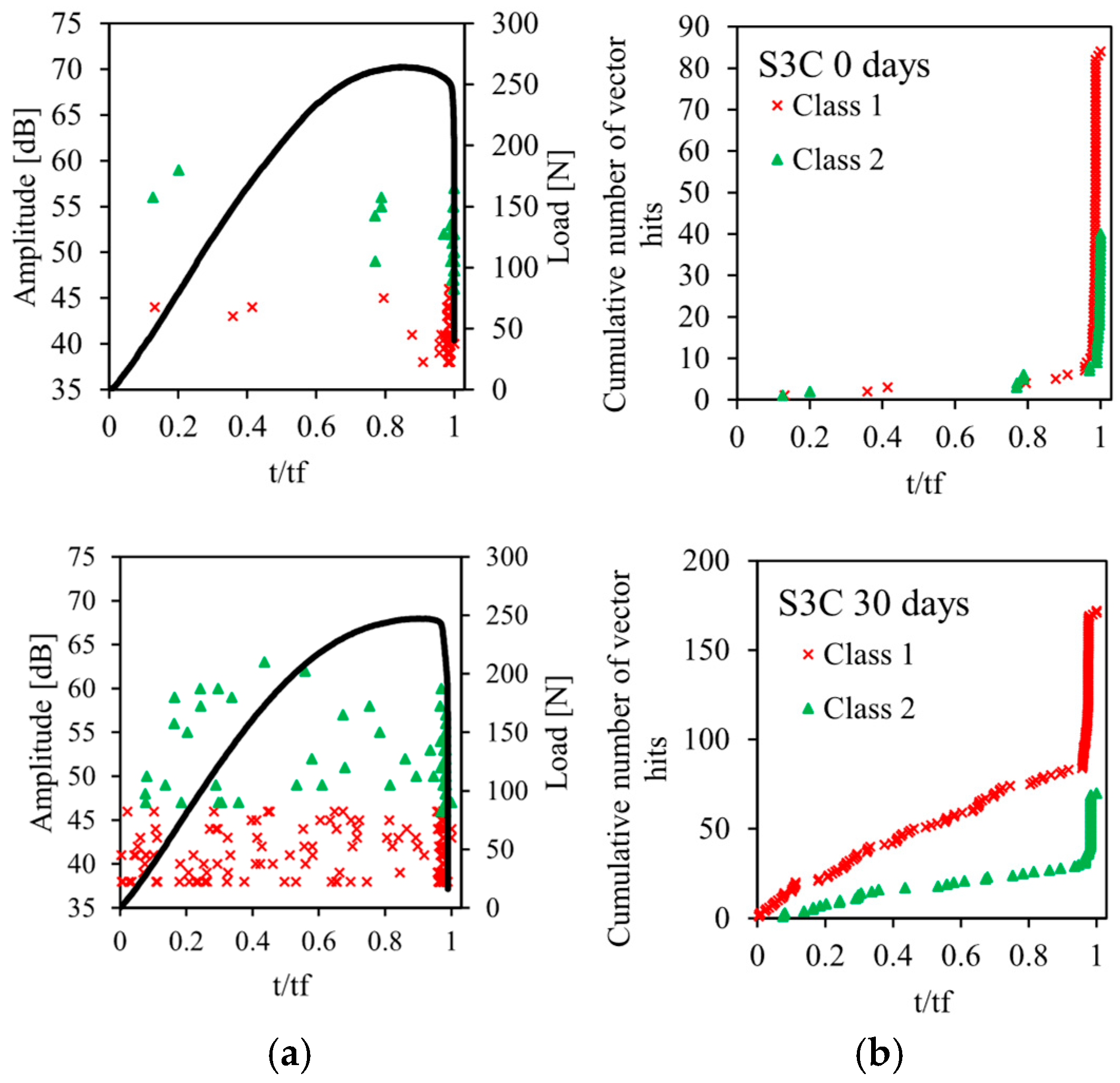

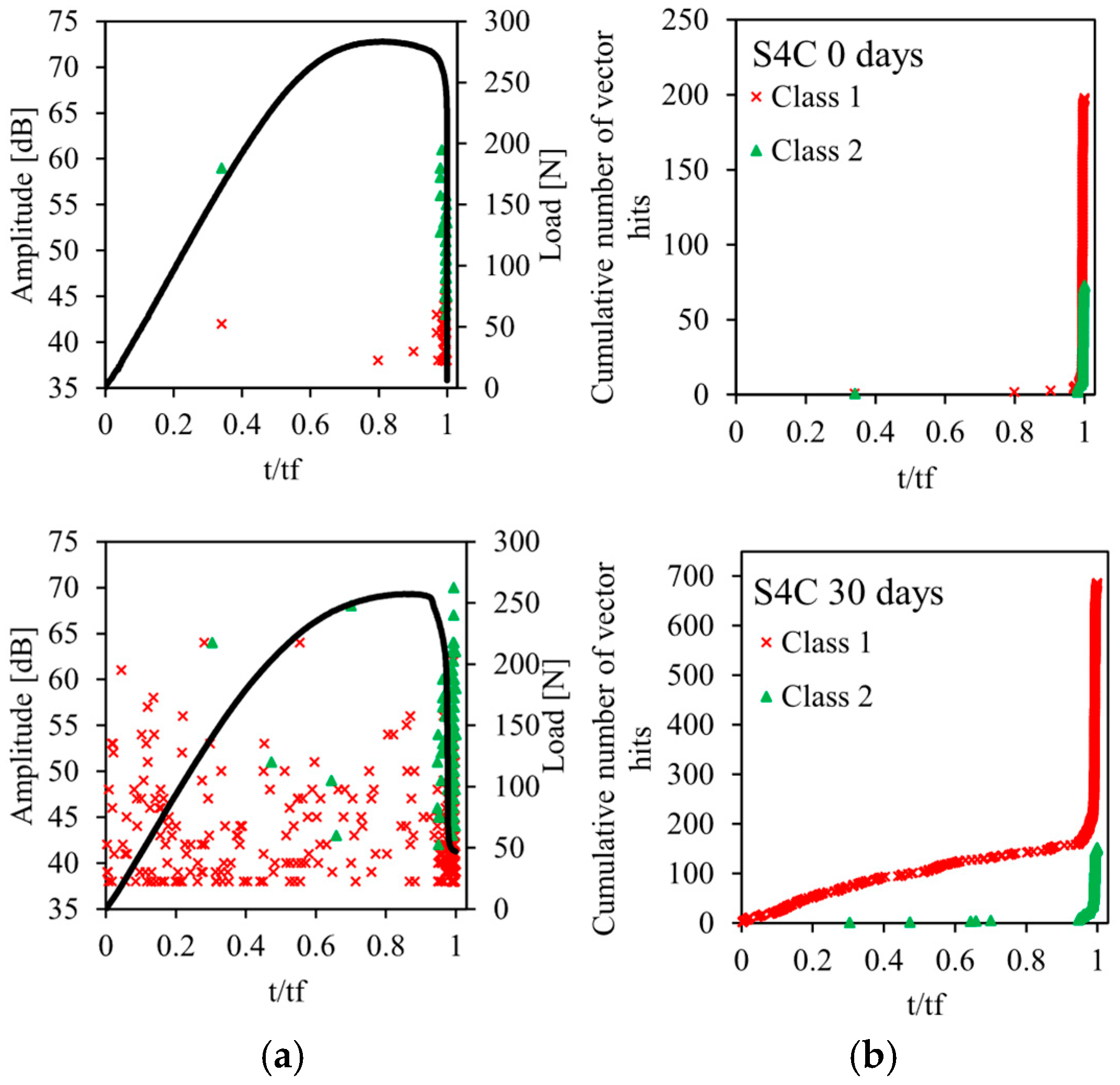

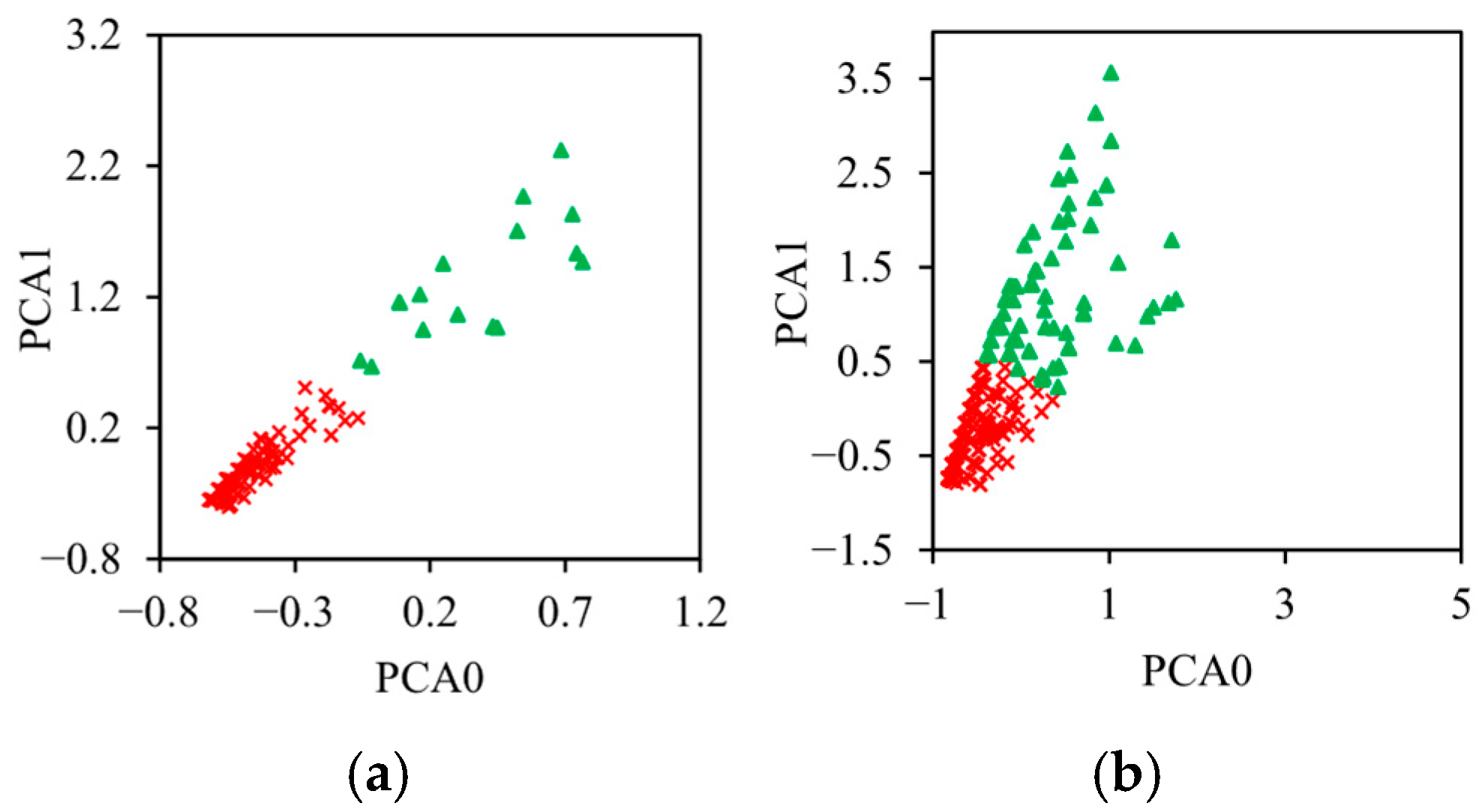

4. Damage Mechanisms of the Sandwiches

5. Conclusions

- Two types of damage mechanisms are detected by acoustic emission: matrix cracking and fiber/matrix delamination.

- Water aging accelerates the onset of damage and its propagation in the bio-based composite material.

- Reduction in mechanical properties.

- The mechanical properties of the four-cell sandwich panels are superior to those of the others.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aktay, L.; Johnson, A.F.; Kröplin, B.H. Numerical modelling of honeycomb core crush behaviour. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2008, 75, 2616–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadepalli, T.P.; Mantena, P.R. Numerical and experimental blast response characterization of sandwich composite structural panels. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2013, 15, 110–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvestani, H.Y.; Akbarzadeh, A.H.; Mirbolghasemi, A.; Hermenean, K. 3D printed meta-sandwich structures: Failure mechanism, energy absorption and multi-hit capability. Mater. Des. 2018, 160, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solak, A.; Temiztaş, B.A.; Bolat, B. Investigation of the effect of wavy honeycomb on the bending performance of the sandwich structure. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2022, 24, 1905–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Hui, D. Mechanical behaviors of inclined cell honeycomb structure subjected to compression. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 110, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essassi, K.; Rebiere, J.L.; El Mahi, A.; Ben Souf, M.A.; Bouguecha, A.; Haddar, M. Experimental and analytical investigation of the bending behaviour of 3D-printed bio-based sandwich structures composites with auxetic core under cyclic fatigue tests. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 131, 105775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.H.; Heidari-Rarani, M.; Torabi, K. A novel graded auxetic honeycomb core model for sandwich structures with increasing natural frequencies. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2022, 24, 1313–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, R.; Subramani, P.; Lisner, T.; Rana, S.; Ghiassi, B.; Fangueiro, R.; Oliveira, D.V.; Lourenco, P.B. Development, characterization and analysis of auxetic structures from braided composites and study the influence of material and structural parameters. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 87, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, H.G. Analysis and Design of Structural Sandwich Panels: The Commonwealth and International Library: Structures and Solid Body Mechanics Division; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; ISBN 9780080128702. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Walczyk, D.; McIntyre, G.; Bucinell, R.; Li, B. Bioresin infused then cured mycelium-based sandwich-structure biocomposites: Resin transfer molding (RTM) process, flexural properties, and simulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Walczyk, D.; McIntyre, G.; Bucinell, R.; Tudryn, G. Manufacturing of biocomposite sandwich structures using mycelium-bound cores and preforms. J. Manuf. Proc. 2017, 28, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Yeong, W.Y. Design and printing strategies in 3D bioprinting of cell-hydrogels: A review. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 2856–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.C.; Sheikh, A.A. 3D printing in aerospace and its long-term sustainability. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2015, 10, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, A.; Rebiere, J.L.; El Mahi, A.; Beyaoui, M.; Haddar, M. Experimental and finite element analyses of a 3D printed sandwich with an auxetic or non-auxetic core. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2023, 25, 426–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Kasal, B.; Huang, L. A review of recent research on the use of cellulosic fibres, their fibre fabric reinforced cementitious, geo-polymer and polymer composites in civil engineering. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 92, 94–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamboulis, A.; Baley, C. Effects of Environ-mental Conditions on Mechanical and Physical Properties of Flax Fibres. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2001, 32, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodaghi, M.; Serjouei, A.; Zolfagharian, A.; Fotouhi, M.; Rahman, H.; Durand, D. Reversible energy absorbing meta-sandwiches by FDM 4D printing. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 173, 105451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer Kerche, E.; Silveira Caldas, B.G.; Carvalho, R.F.; Amico, S.C. Mechanical response of sisal/glass fabrics reinforced polyester–polyethylene terephthalate foam core sandwich panels. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2022, 24, 1993–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.; Dhakal, H.N.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Barouni, A.; Zahari, R. Enhancement of impact toughness and damage behaviour of natural fibre reinforced composites and their hybrids through novel improvement techniques: A critical review. Compos. Struct. 2021, 259, 113496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture, A.; Lebrun, G.; Laperrière, L. Mechanical properties of polylactic acid (PLA) composites reinforced with unidirectional flax and flax-paper layers. Compos. Struct. 2016, 154, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, H.; Rebiere, J.L.; Makni, A.; Taktak, M.; El Mahi, A.; Haddar, M. Numerical and experimental characterization of the dynamic properties of flax fiber reinforced composites. Int. J. Appl. Mech. 2016, 8, 1650068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allagui, S.; El Mahi, A.; Rebiere, J.L.; Beyaoui, M.; Bouguecha, A.; Haddar, M. Effect of recycling cycles on the mechanical and damping properties of flax fibre reinforced elium composite: Experimental and numerical studies. J. Renew. Mater. 2021, 9, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essassi, K.; Rebiere, J.L.; El Mahi, A.; Ben Souf, M.A.; Bouguecha, A.; Haddar, M. Investigation of the static behavior and failure mechanisms of a 3D printed bio-based sandwich with auxetic core. Int. J. Appl. Mech. 2020, 12, 2050051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, E.; García-Manrique, J.A. Water absorption behaviour and its effect on the mechanical properties of flax fibre reinforced bioepoxy composites. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2015, 2015, 390275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gager, V.; Le Duigou, A.; Bourmaud, A.; Pierre, F.; Behlouli, K.; Baley, C. Understanding the effect of moisture variation on the hygromechanical properties of porosity-controlled nonwoven biocomposites. Polym. Test. 2019, 78, 105944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaloni, D.; Melelli, A.; Shah, D.U.; Baley, C.; Bourmaud, A. Influence of water ageing on the mechanical properties of flax/PLA non-woven composites. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 200, 109957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslinda, A.B.; Majid, M.A.; Ridzuan, M.J.M.; Afendi, M.; Gibson, A. Effect of water absorption on the mechanical properties of hybrid interwoven cellulosic-cellulosic fibre reinforced epoxy composites. Compos. Struct. 2017, 167, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesentini, Z.; El Mahi, A.; Rebiere, J.L.; El Guerjouma, R.; Beyaoui, M.; Haddar, M. Effect of hydric aging on the static and vibration behavior of 3D printed bio-based flax fiber reinforced poly-lactic acid composites. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2022, 30, 09673911221081826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesentini, Z.; El Mahi, A.; Rebiere, J.L.; El Guerjouma, R.; Beyaoui, M.; Haddar, M. Static and Fatigue Tensile Behavior and Damage Mechanisms Analysis in Aged Flax Fiber/PLA Composite. Int. J. Appl. Mech. 2022, 14, 2250080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, H.N.; Zhang, Z.A.; Richardson, M.O. Effect of water absorption on the mechanical properties of hemp fibre reinforced unsaturated polyester composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allagui, S.; El Mahi, A.; Rebiere, J.L.; Beyaoui, M.; Bouguecha, A.; Haddar, M. Thermoplastic Elium Recycling: Mechanical Behaviour and Damage Mechanisms Analysis by Acoustic Emission. In Advances in Acoustics and Vibration III; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.G.; He, M.; Deshpande, V.S.; Hutchinson, J.; Jacobsen, A.; Carter, W. Concepts for enhanced energy absorption using hollow micro-lattices. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2010, 37, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahardoli, S. Flexural behavior of sandwich panels with 3D printed cellular cores and aluminum face sheets under quasi-static loading. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2023, 25, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.B.; Wadley, H.N.G.; McMeeking, R.M. Mechanical metamaterials at the theoretical limit of isotropic elastic stiffness. Nature 2017, 543, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likas, A.; Vlassis, N.; Verbeek, J.J. The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern Recognit. 2003, 36, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G.W.; Cooper, M.C. An examination of procedures for determining the number of clusters in a data set. Psychometrika 1985, 50, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasopoulos, A. Pattern recognition techniques for acoustic emission based condition assessment of unfired pressure vessels. J. Acoust. Emiss. 2005, 23, 318. [Google Scholar]

- Almudaihesh, F.; Grigg, S.; Holford, K.; Pullin, R.; Eaton, M. An Assessment of the Effect of Progressive Water Absorption on the Interlaminar Strength of Unidirectional Carbon/Epoxy Composites Using Acoustic Emission. Sensors 2021, 21, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crank, J. The Mathematics of Diffusion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.H.; Springer, G.S. Moisture absorption and desorption of composite materials. J. Compos. Mater. 1976, 10, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C393/C393M–16; Standard Test Method for Core Shear Properties of Sandwich Constructions by Beam Flexure. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Osman, E.; Vakhguelt, A.; Sbarski, I.; Mutasher, S. Water absorption behavior and its effect on the mechanical properties of kenaf natural fiber unsaturated polyester composites. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Composites Materials (ICCM’11), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 21–26 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Krishnaraj, V.; Zitoune, R. Sound and vibration damping properties of flax fiber reinforced composites. Proc. Eng. 2014, 97, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, V.; Kumar, C.S.; Santulli, C.; Sarasini, F.; Stanley, A.J. Identification of failure modes in composites from clustered acoustic emission data using pattern recognition and wavelet transformation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2013, 38, 1087–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cells in Width | l (mm) | h (mm) | θ (degree) | t (mm) | b (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1C: 1 cell | 13.3 | 17.04 | −20 | 0.6 | 5 |

| S2C: 2 cells | 6.65 | 8.52 | −20 | 0.6 | 5 |

| S3C: 3 cells | 4.43 | 5.68 | −20 | 0.6 | 5 |

| S4C: 4 cells | 3.32 | 4.26 | −20 | 0.6 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rebiere, J.-L.; El Mahi, A.; Kesentini, Z.; Beyaoui, M.; Haddar, M. Acoustic Emission Analysis of Moisture Damage Mechanisms in 3D Printed Auxetic Core Sandwiches. Sensors 2026, 26, 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031034

Rebiere J-L, El Mahi A, Kesentini Z, Beyaoui M, Haddar M. Acoustic Emission Analysis of Moisture Damage Mechanisms in 3D Printed Auxetic Core Sandwiches. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031034

Chicago/Turabian StyleRebiere, Jean-Luc, Abderrahim El Mahi, Zeineb Kesentini, Moez Beyaoui, and Mohamed Haddar. 2026. "Acoustic Emission Analysis of Moisture Damage Mechanisms in 3D Printed Auxetic Core Sandwiches" Sensors 26, no. 3: 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031034

APA StyleRebiere, J.-L., El Mahi, A., Kesentini, Z., Beyaoui, M., & Haddar, M. (2026). Acoustic Emission Analysis of Moisture Damage Mechanisms in 3D Printed Auxetic Core Sandwiches. Sensors, 26(3), 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031034