In wireless communication systems, modulation recognition serves as a core technology capable of real-time analysis of non-cooperative signal modulation characteristics and accurate determination of their modulation types [

1]. This technology has demonstrated broad application potential in critical fields such as cognitive radio and dynamic spectrum access, as well as radio monitoring and spectrum management [

2]. In the early stages of radio technology development, the electromagnetic environment was relatively ideal, and signal types were limited. As a result, modulation recognition could be achieved through manual observation of frequency-domain spectral lines and time-domain waveforms, provided that expertise in the communication domain was available. Recently, with the continuous evolution of 5G/6G communications [

3,

4], the Internet of Things [

5], and integrated space–air–ground networks [

6], the demand for efficient and robust modulation recognition techniques is growing increasingly urgent.

1.1. Related Works and Motivations

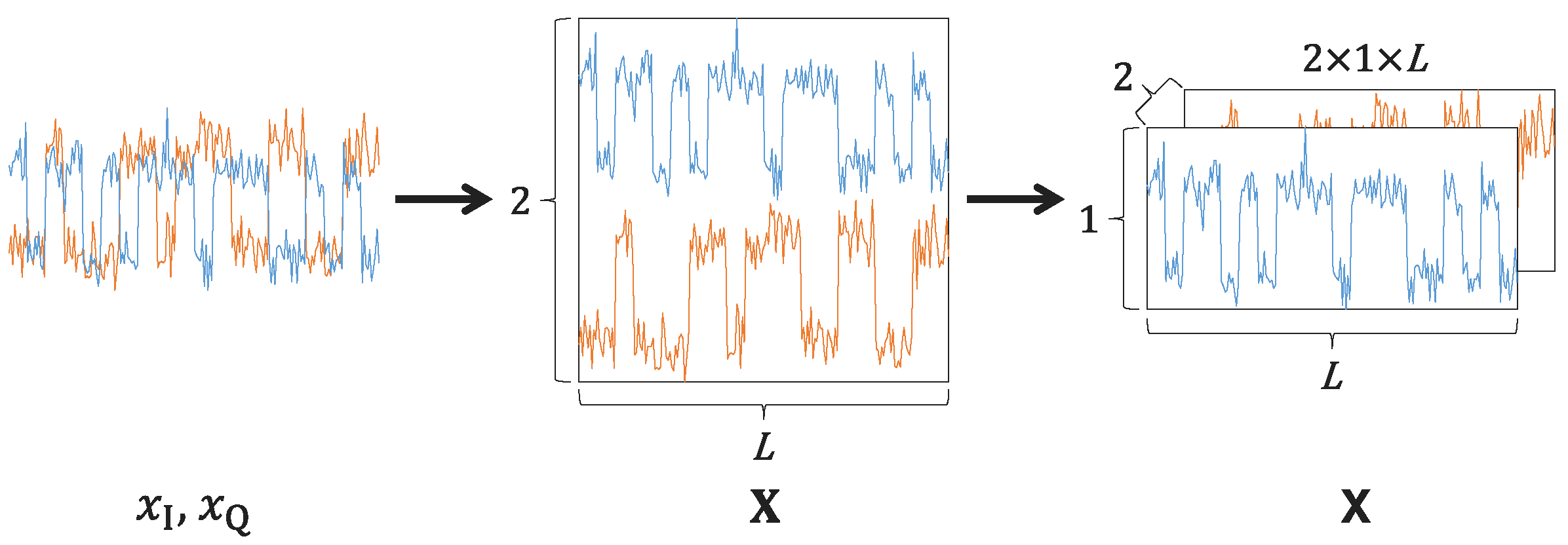

Typical modulation recognition comprises a three-stage pipeline consisting of data preprocessing, feature selection, and classification. In the data preprocessing stage, operations such as outlier handling and data type conversion are implemented on the received signal to facilitate subsequent feature selection [

7]. In the feature selection stage, intermediate representations of the signal, such as features, sequences, or images, are used to obtain discriminative characteristics. The representations are derived from the raw signal, including, but not limited to, cumulant [

8] and circular [

9] features. The sequence representation includes the raw in-phase/quadrature (I/Q) sequences [

10], and other transformed sequences such as the amplitude, phase, and frequency sequences, along with their various combinations [

11]. The image representation is formed by two primary types: constellation diagrams [

12] and time–frequency images [

13]. In the classification stage, traditional machine learning (ML) classifiers, for example, K-nearest neighbors (KNN) [

14] and support vector machine (SVM) [

15], were extensively employed. These methods, however, often demand considerable expertise and effort for manual feature crafting and parameter calibration, a process that is both time-consuming and susceptible to suboptimal outcomes. In contrast, deep learning (DL) involves two primary components in the classification stage: a feature extractor and a classifier. The former is responsible for extracting more discriminative high-dimensional features, while the latter operates on these features for final classification. From the network architecture perspective, the feature extractor is often called a backbone network, while the classifier is often called a classification head. These two components are trained end-to-end, without the need for manual feature engineering.

The rise of DL has catalyzed a paradigm shift in modulation recognition, establishing DL-based methods as a dominant approach. Owing to their raw format, I/Q sequences are frequently employed as inputs to DL models [

16,

17,

18]. This approach avoids explicit signal transformation, thereby saving computational time and removing the need for manual parameter tuning. The convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture, proven successful in computer vision, has also been applied to modulation recognition, leveraging its strengths in spatial feature extraction. Specifically, the CNN in [

10], despite its simple few-layer architecture, demonstrated superior accuracy over traditional ML classifiers. Moreover, the residual network (ResNet) [

19], originally developed for image classification, has been appropriately adapted to handle the modulation recognition task [

20]. Comparative analysis confirms that ResNet outperforms simple CNNs in classification accuracy while requiring fewer parameters. Furthermore, by designing specific convolutional blocks, an efficient CNN architecture named MCNet was proposed in [

21], achieving even higher accuracy. The applicability of successful DL architectures has extended beyond their original domains; models such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [

22], including the long short-term memory (LSTM) [

23] and gated recurrent unit (GRU) [

24] variants, along with Transformers [

25,

26], prominent in natural language processing, have found effective use in modulation recognition. Hybrid models combining the aforementioned DL architectures have also been explored [

27,

28]. However, conventional DL methods suffer from an inherent limitation: they require a large amount of labeled training data to achieve high accuracy, which is often unavailable in practical scenarios, especially in non-cooperative situations. Driven by the need to learn effectively from scarce data, few-shot learning (FSL) has drawn significant research interest.

The core objective of FSL is to learn a model that can achieve high classification accuracy with only a few training samples per class [

29]. In recent years, numerous FSL methods have been proposed. These approaches can be broadly divided into three categories. The first category of FSL methods focuses on improving data utilization, typically through data augmentation techniques. For example, flipping, truncation, and rotation operations can be applied to I/Q sequences to effectively augment the existing few-shot dataset and enhance model generalization [

30,

31]. Consequently, standard network architectures, including CNN, ResNet, and the other advanced models mentioned above, are readily applicable in few-shot settings. Semi-supervised learning techniques that combine both labeled and unlabeled data have also been explored. This can somewhat reduce the need for labeled data while still leveraging the unlabeled data to improve model generalization. Specifically, a hybrid model using two parallel auto-encoders for label-agnostic feature extraction was proposed in [

32], making it naturally suitable for semi-supervised scenarios. In addition, a deep residual shrinkage network [

33] designed for this learning setting was explored. However, when the available samples are severely limited (i.e., in cases of acute scarcity), the effectiveness of such approaches is limited. The second category of FSL methods focuses on improving model architecture through deliberate design informed by expertise. For example, the capsule network [

34] was introduced to better preserve the spatial relationships within signals through its specialized capsule layers. Moreover, a modular FSL framework named MsmcNet [

35], which integrates dedicated signal processing modules for high-level feature extraction, was also investigated. Alternatively, the few-shot classification problem can be addressed within a hybrid inference framework. For example, this can be achieved by designing a two-channel CNN and a temporal convolutional network to extract spatial and temporal features in parallel, followed by measuring sample similarity in these dual feature spaces [

36]. Similarly, by combining a convolutional layer, residual modules, multi-component down sampling modules with a fully connected (FC) layer, the multi-component extraction network was proposed in [

37]. In addition, the multi-scale feature fusion and distribution similarity network [

38] that can effectively extract features across different receptive fields was also studied. These methods show satisfactory classification performance in few-shot modulation recognition (FSMR) tasks. However, the reliance of these methods on particular network architectures may hinder generalization across diverse tasks. The third category of FSL methods focuses on learning transferable knowledge (or representations) through the paradigm of transfer learning (TL). By distilling generalizable knowledge from class-disjoint auxiliary datasets, TL enables rapid adaptation to novel tasks with limited samples [

39]. It can effectively bridge the data scarcity gap and thus has emerged as a promising alternative in the FSL domain. The efficacy of TL for FSMR has been established by several studies [

40,

41,

42], which report high accuracy with few samples per class, surpassing traditional approaches. Different from TL, meta-learning follows a “learning-to-learn” paradigm. It trains a model by constructing numerous few-shot tasks (episodes) from the auxiliary dataset to simulate the target few-shot scenario [

43]. Two representative meta-learning methods, the prototypical network [

44] and relation network [

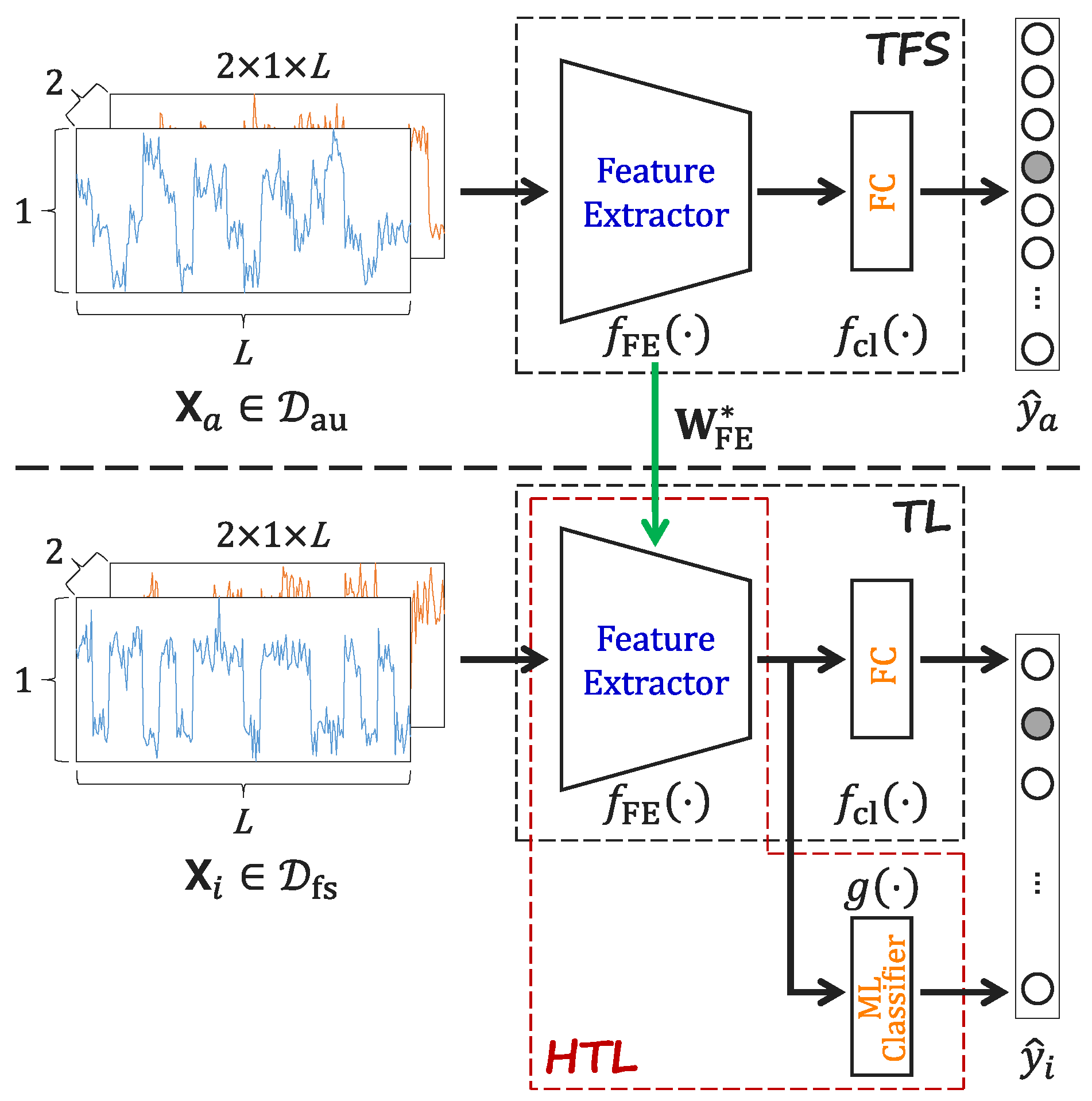

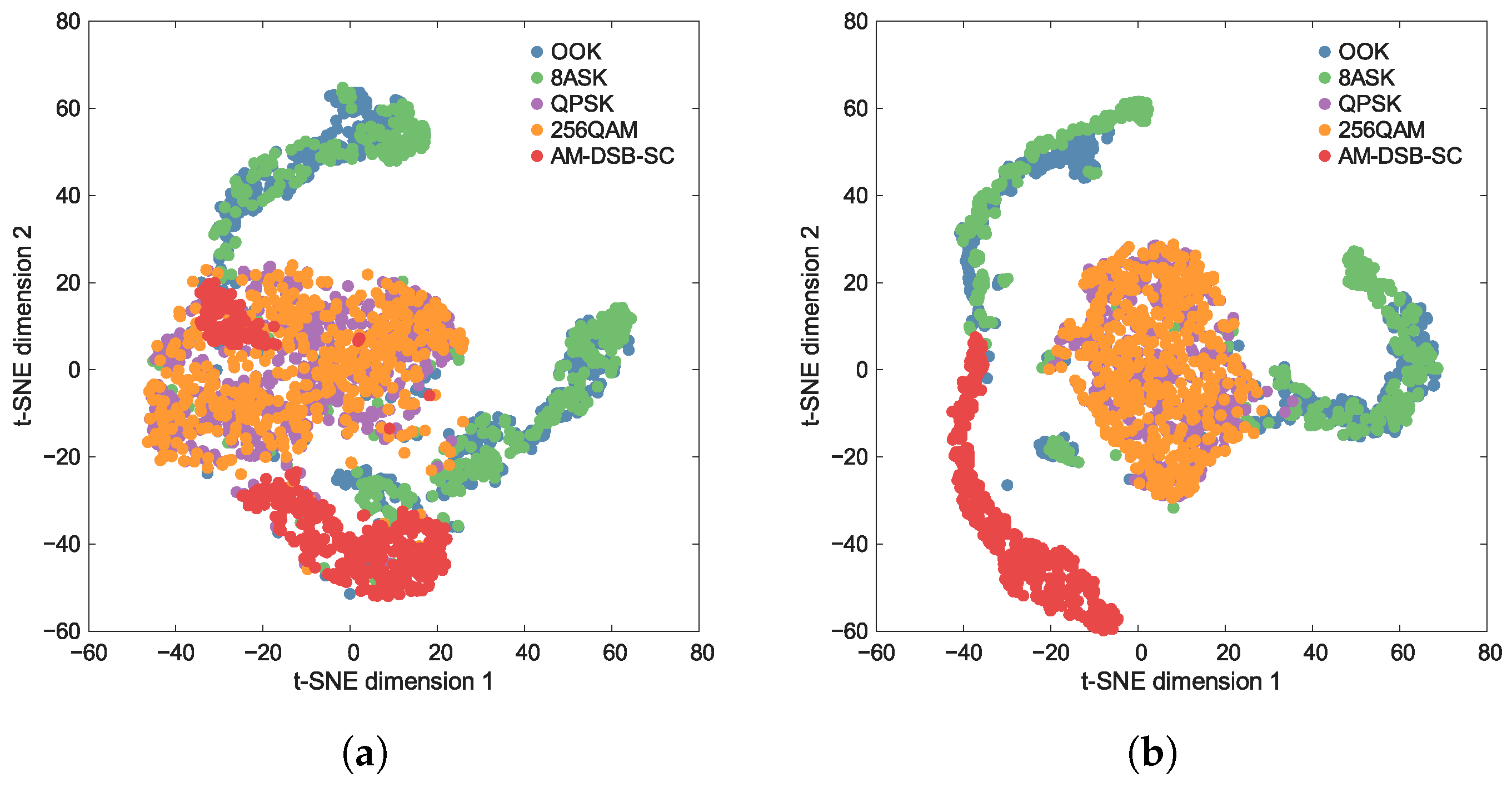

45], have attained notable accuracy in FSMR tasks. In this type of approach, advanced network architectures can serve as the backbone for feature learning. At its core, both TL and meta-learning operate on the principle of leveraging pre-trained models to circumvent the need for training from scratch (TFS). This enables the training process to be substantially simplified by leveraging informed prior knowledge rather than beginning from a completely blank slate. This study is primarily centered on the TL paradigm, yet remains readily extensible to the meta-learning paradigm. Our analysis will reveal that despite TL’s ability to reduce sample dependence, the one- or few-shot scenario presents a persistent and severe challenge. The underlying issue may lie in the insufficiency of data provided during the fine-tuning stage of TL to properly train the classifier network, resulting in suboptimal performance in few-shot settings. Unlike prior works that primarily employ dedicated networks as backbones to extract distinctive features, this study shifts focus towards enhancing classifier performance, placing less emphasis on the feature extractor itself.

1.2. Contributions and Organization

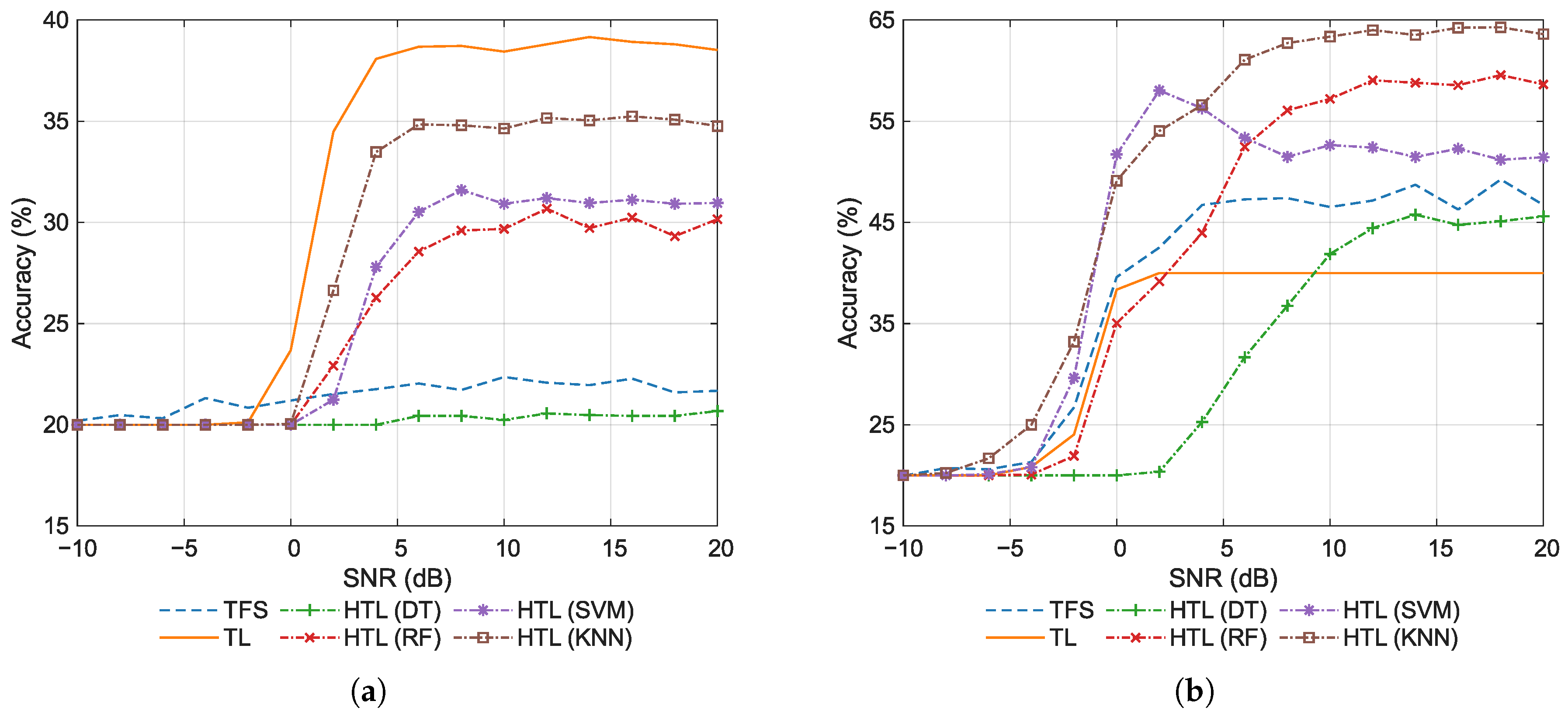

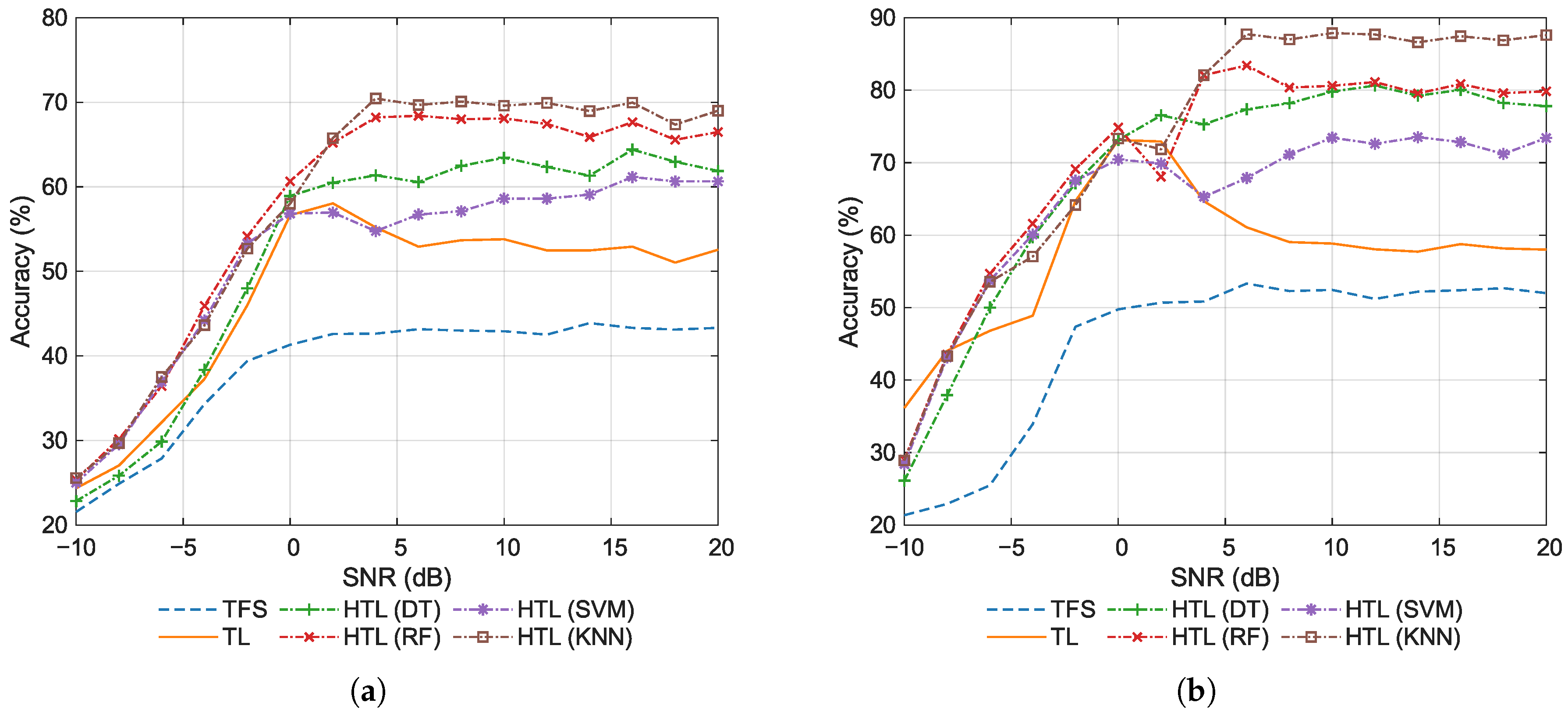

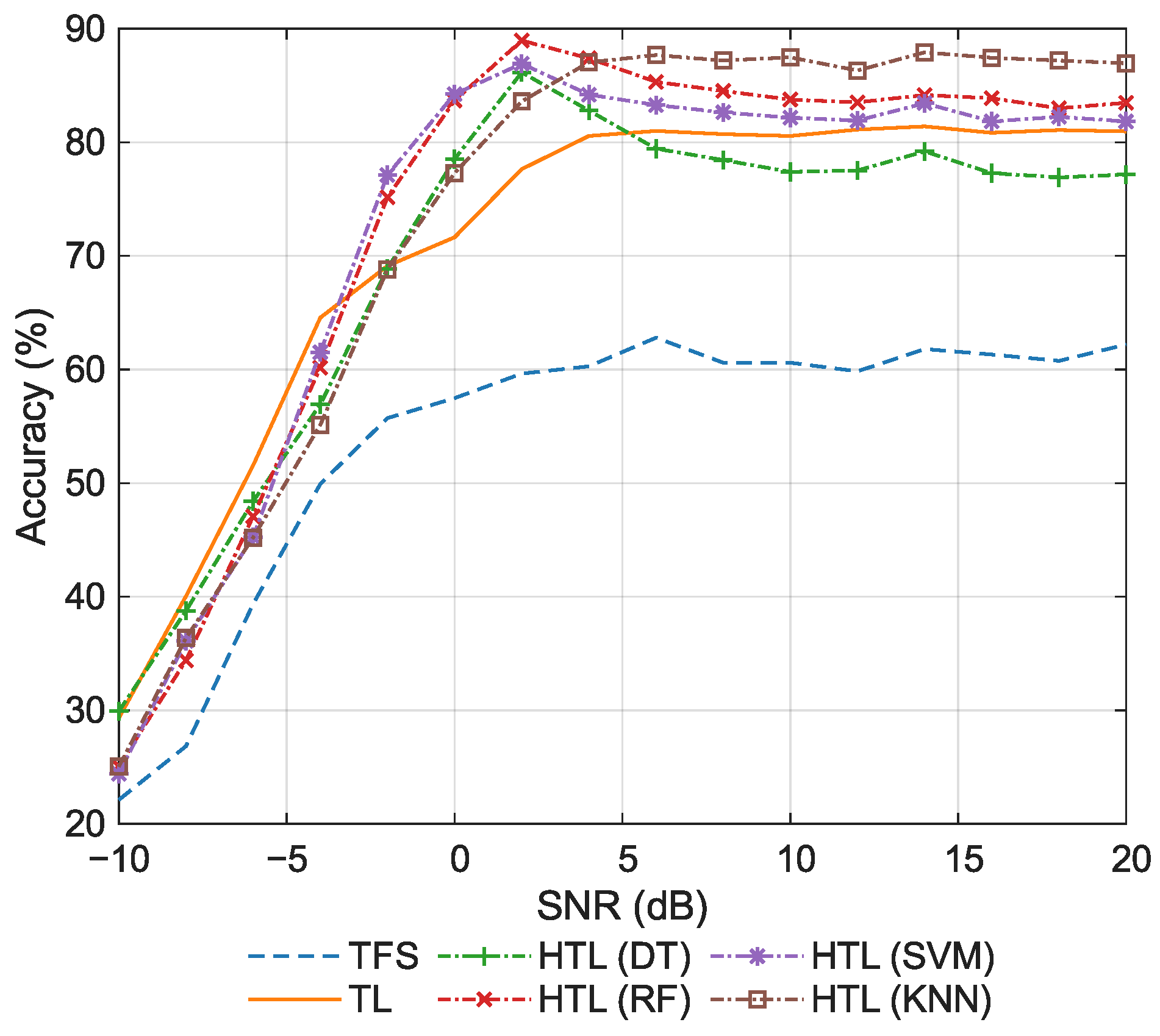

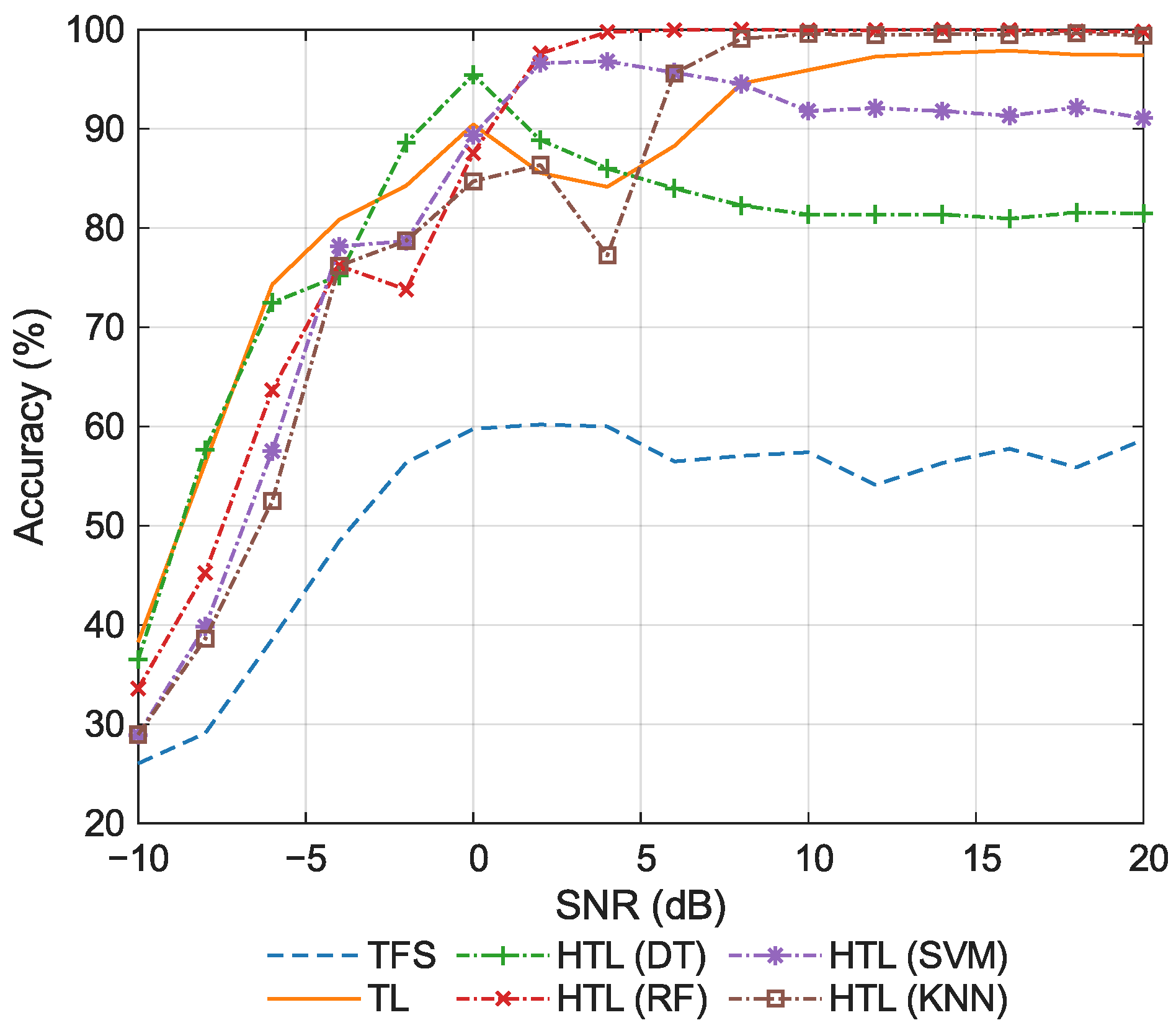

To overcome the practical limitations of conventional TL, this paper introduces a hybrid transfer learning (HTL) approach that synergistically integrates TL with ML, thereby marrying the representation power of DL to the robustness of ML. The HTL approach operates in two stages. In the first stage, TL is employed to obtain an effective feature extractor, thereby retaining DL’s advantage of automated feature extraction. In the second stage, the extracted deep features are used to train a traditional ML classifier, which preserves ML’s benefits of rapid, non-iterative training and robust few-shot performance. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

We propose to incorporate traditional ML classifiers within the TL framework to achieve high classification accuracy in FSMR tasks.

We validate the proposed method through a series of experiments, with comparisons to conventional TFS and TL approaches.

We examine several parameters that may influence practical performance, aiming to assess their impact on classification accuracy.

We investigate the integration of HTL with meta-learning paradigms, establishing its effectiveness and transferability.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the signal model along with its associated data preprocessing steps, and formulates the FSMR problem.

Section 3 reviews the foundational TFS and TL approaches, and proposes the HTL approach incorporating an introduction to the specific ML classifiers.

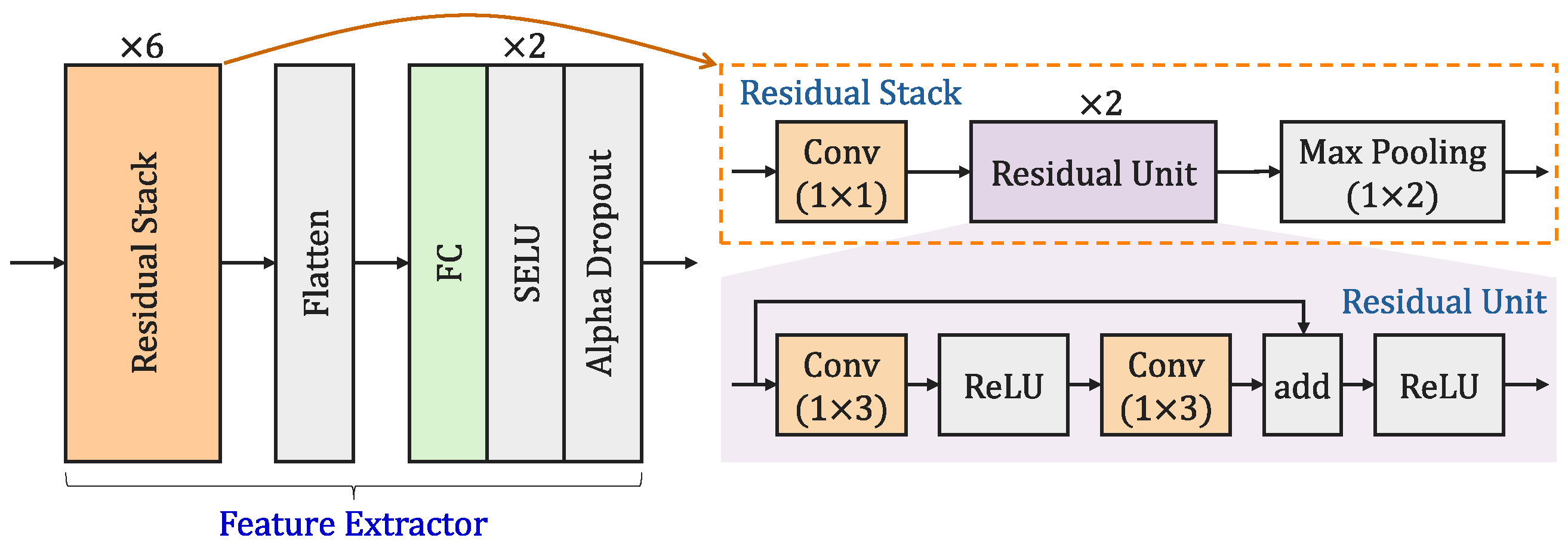

Section 4 introduces the backbone network to extract discriminative features for classification.

Section 5 describes the dataset used in this study, and provides experimental results and analysis. Finally,

Section 6 concludes this paper and discusses future work.