A Lightweight Modified Adaptive UNet for Nucleus Segmentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We develop a new light-weight adaptive UNet architecture called mA-UNet, which specializes in predicting small foreground objects like a nucleus.

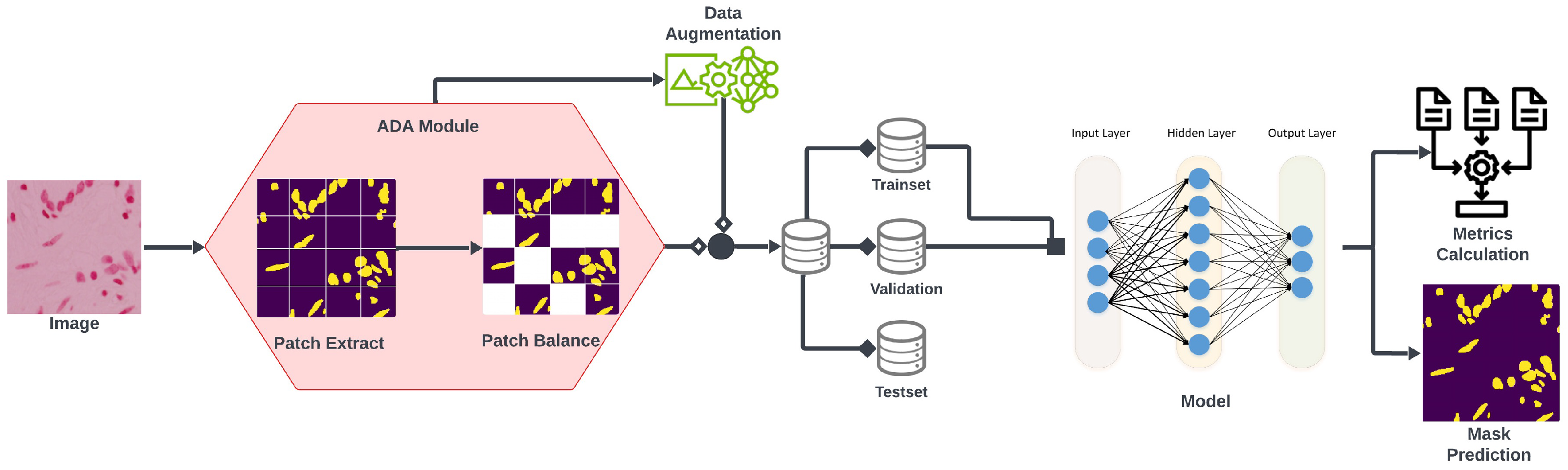

- The proposed framework uses an ADA module [35], an enhanced augmentation method that extracts patches using unit kernel convolution, leading to a more complete semantic representation of an imbalanced dataset and a faster learning rate for the model.

- Both qualitative and quantitative studies show superior results compared to other previously proposed architectures.

- Due to its lightweight nature and reduced parameter count compared to other cutting-edge models, the proposed architecture possesses the capability to retain information efficiently. Consequently, it takes shorter training times, rendering it a dependable solution for automated medical image segmentation in real-world applications.

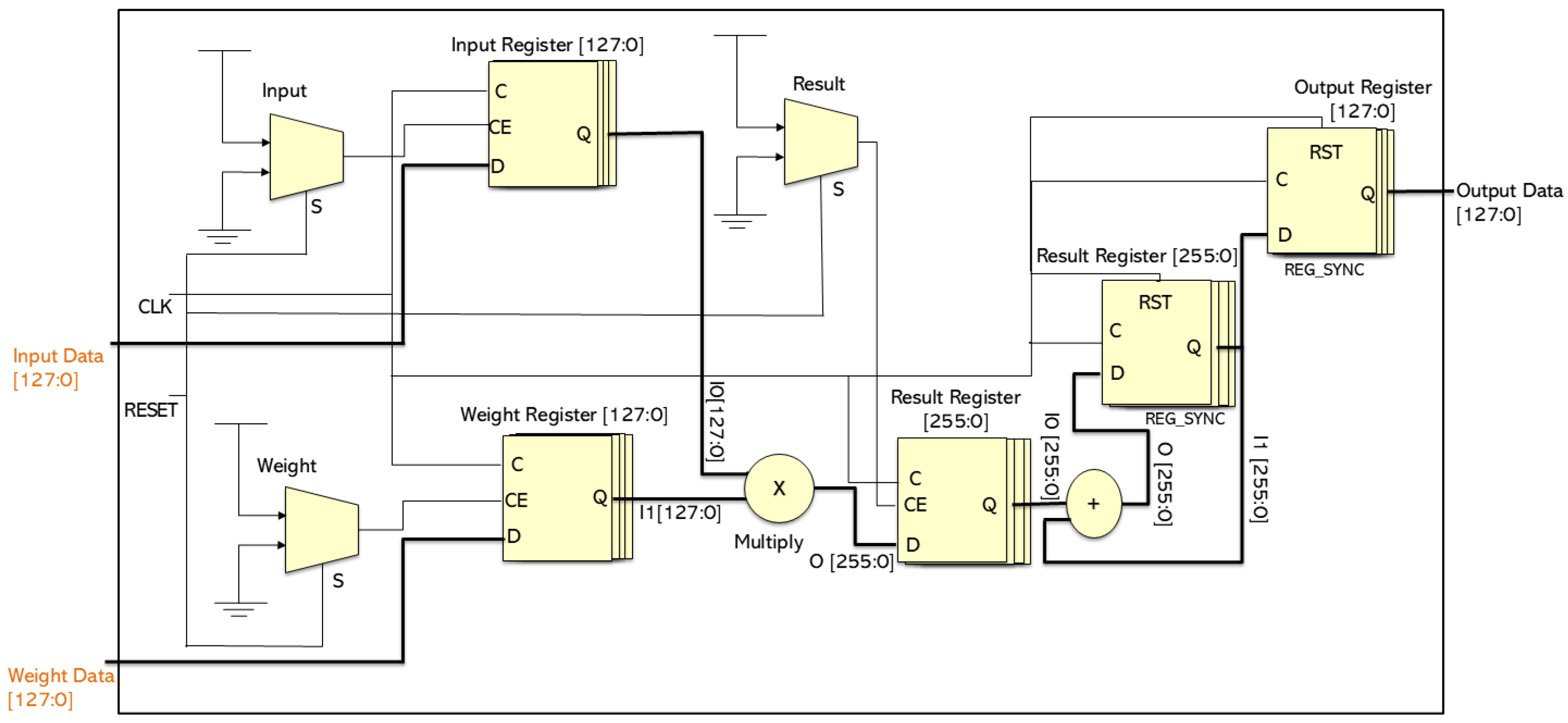

- The mA-UNet model is implemented on the Zynq Ultra-Scale+ using VHDL, demonstrating its suitability for high-performance applications on advanced FPGA architectures.

2. The Proposed Method

2.1. Adaptive Augmentation

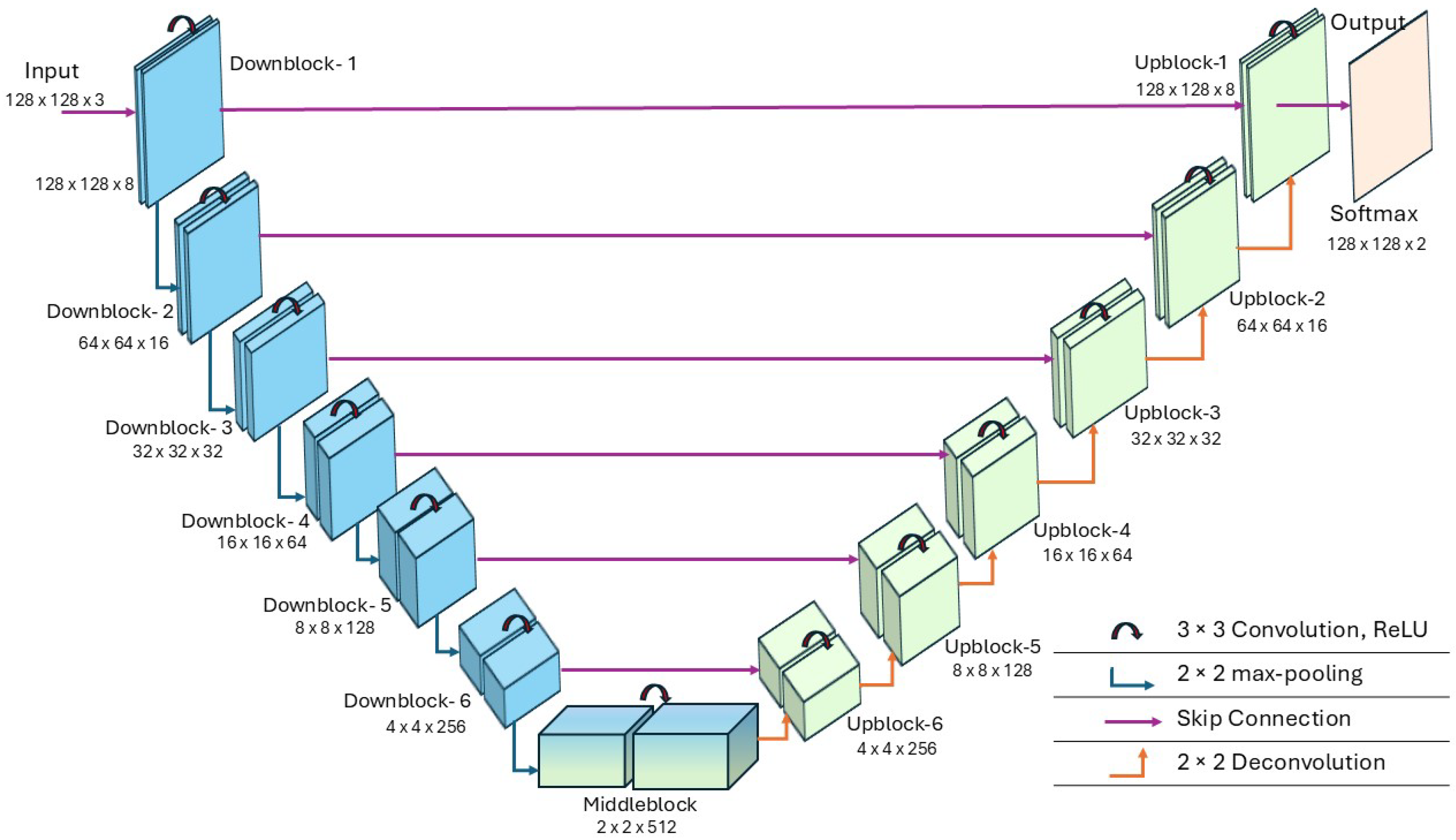

2.2. Proposed mA-UNet

2.3. Hyperparameter Tuning

2.4. Loss Function

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

2.6. mA-UNET Architecture

3. Implementation and Experimental Results

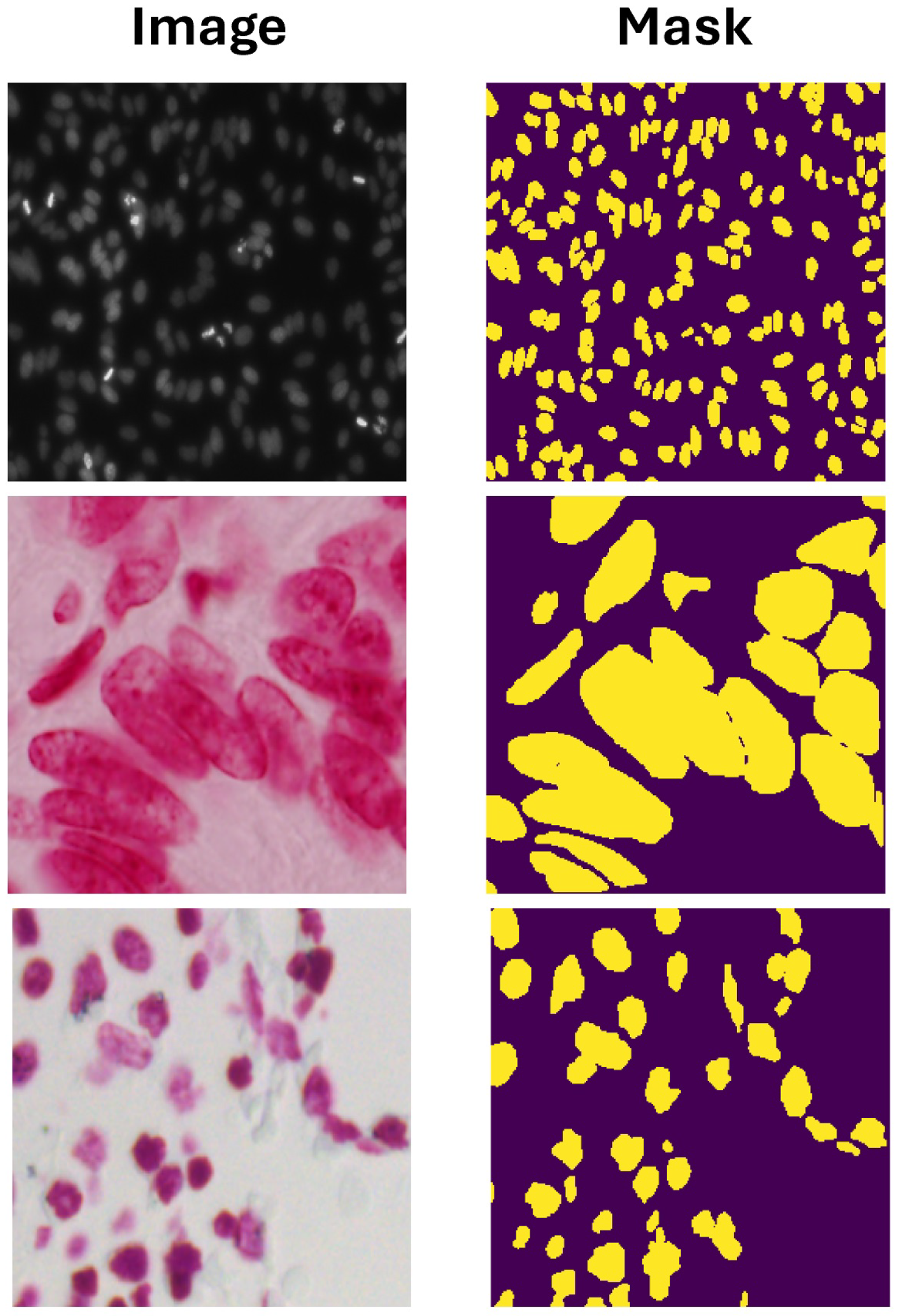

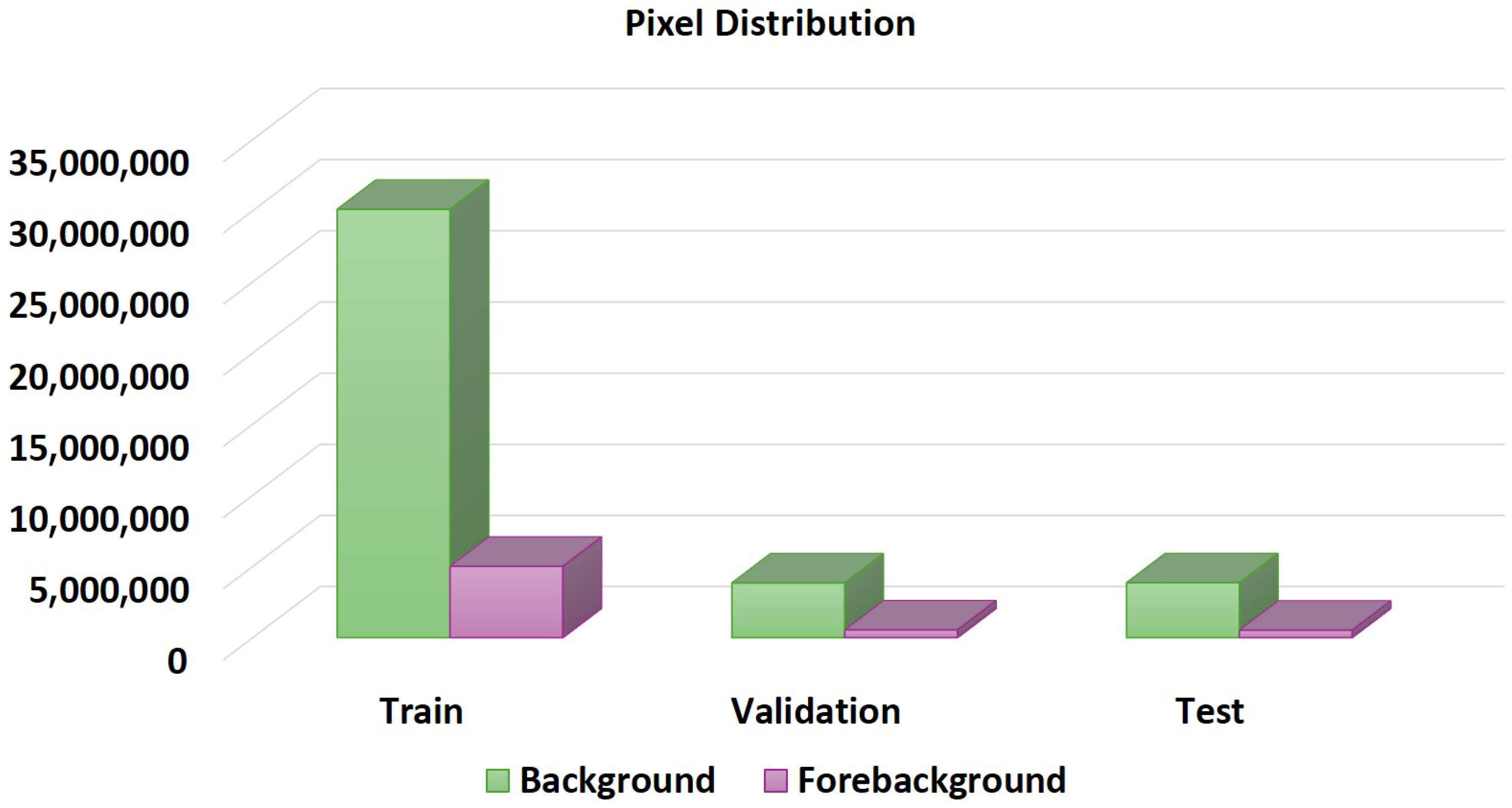

3.1. Dataset

3.2. Training

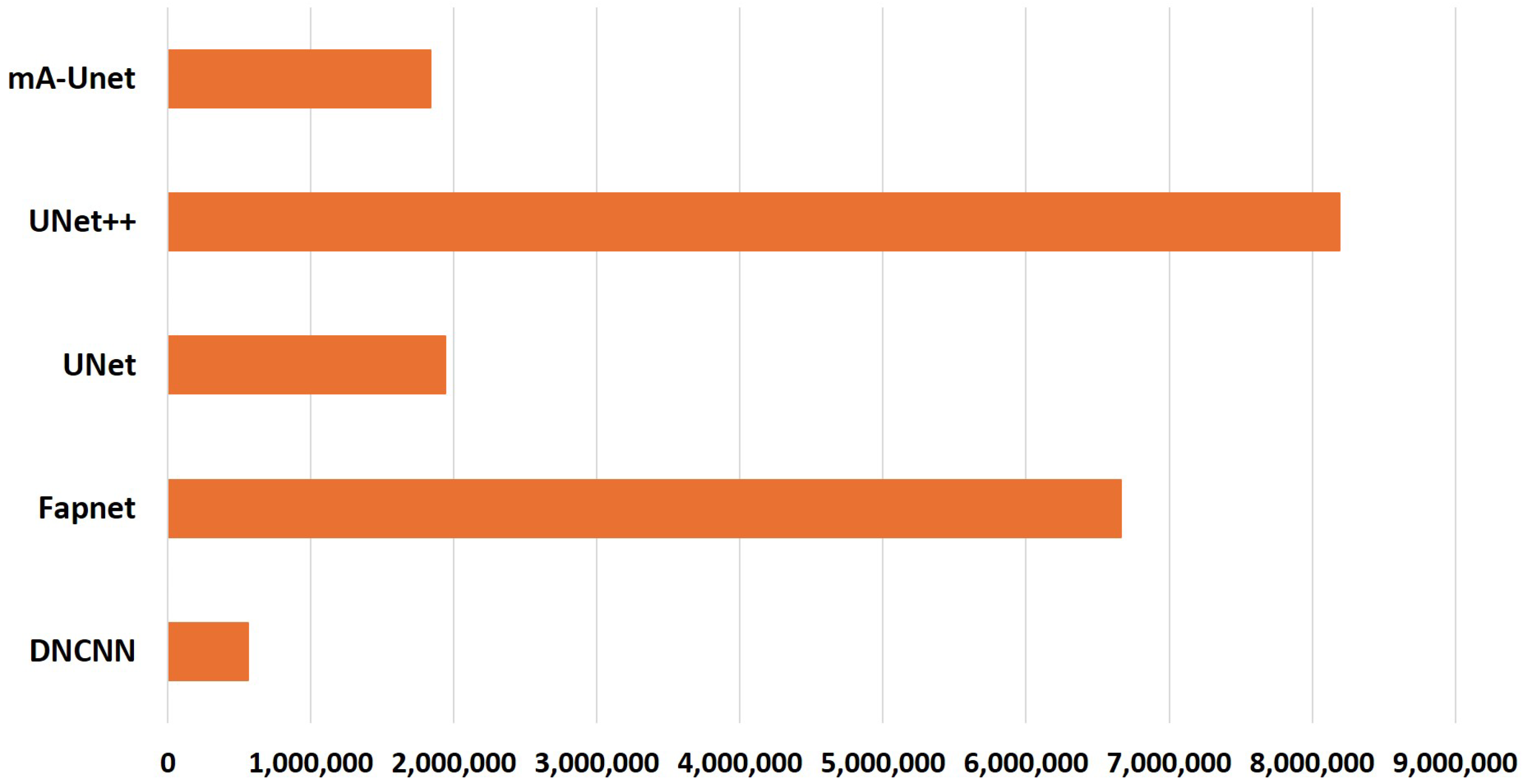

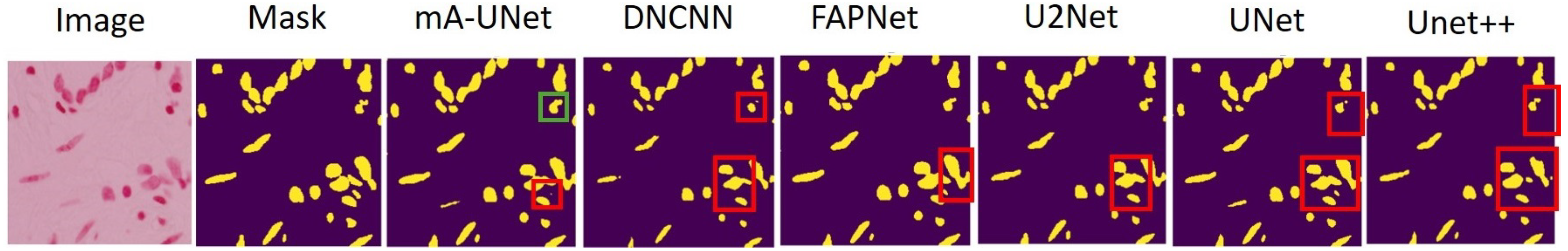

3.3. Experimental Results Analysis

3.4. Hardware Resources Utilization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, S.; Lai, J. EdgeMedNet: Lightweight and accurate U-Net for implementing efficient medical image segmentation on edge devices. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 70, 4329–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eda, J.; Mohaidat, T.; Niloy, S.I.; Niu, Z.; Khan, M.R.K.; Khalil, K. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: A comprehensive survey on AI-driven diagnosis and patient monitoring. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 190, 114429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ali, H.; Shah, S.A.A.; Shahzad, A. Implementation of a modified U-Net for medical image segmentation on edge devices. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 4593–4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Liu, M. Domain adaptation for medical image analysis: A survey. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 69, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Liu, H.; Song, E.; Xu, X.; Liao, Y.; Ye, G.; Hung, C.C. A 3-D Anatomy-Guided Self-Training Segmentation Framework for Unpaired Cross-Modality Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 2024, 8, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jiao, L.; Shang, R.; Liu, X.; Li, R.; Xu, L. EPT-Net: Edge Perception Transformer for 3D Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 42, 3229–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dai, W.; Yu, J.; Liang, P.; Kong, D. MTANet: Multi-Task Attention Network for Automatic Medical Image Segmentation and Classification. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kuang, T.; Deng, H.; Fung, S.H.; Gateno, J.; Xia, J.J.; Yap, P.T. Dual Adversarial Attention Mechanism for Unsupervised Domain Adaptive Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2022, 41, 3445–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhou, S.; Xiong, Z.; Wu, F. Cross-resolution distillation for efficient 3D medical image registration. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 7269–7283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Shen, M.; Yang, J.; Yang, G.Z. Reliable label-efficient learning for biomedical image recognition. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 66, 2423–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lang, R.; Li, R.; Zhang, J. NRTR: Neuron Reconstruction With Transformer From 3D Optical Microscopy Images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Chen, H. Efficient Supervised Pretraining of Swin-Transformer for Virtual Staining of Microscopy Images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 1388–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Quintana, J.A.; Salazar-Gonzalez, E.A.; Chacon-Murguia, M.I.; Arzate-Quintana, C. Novel Extreme-Lightweight Fully Convolutional Network for Low Computational Cost in Microbiological and Cell Analysis: Detection, Quantification, and Segmentation. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Owusu, S.; Bracher, S.; Bosshardt, D.D.; Pretterklieber, M.; Zysset, P. Automatic segmentation of cortical bone microstructure: Application and analysis of three proximal femur sites. Bone 2025, 193, 117404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez Guatemala-Sanchez, V.Y.; Peregrina-Barreto, H.; Lopez-Armas, G. Nuclei Segmentation on Histopathology Images of Breast Carcinoma. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Virtual, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 2622–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S.; Memiş, A.; Varl, S. Nuclei Segmentation in Colon Histology Images by Using the Deep CNNs: A U-Net Based Multi-class Segmentation Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2022 Medical Technologies Congress (TIPTEKNO), Antalya, Turkey, 31 October–2 November 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Kumar, N.; Patil, A.; Kurian, N.C.; Rane, S.; Graham, S.; Vu, Q.D.; Zwager, M.; Raza, S.E.A.; Rajpoot, N.; et al. MoNuSAC2020: A Multi-Organ Nuclei Segmentation and Classification Challenge. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2021, 40, 3413–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.C.; Roth, H.R.; Gao, M.; Lu, L.; Xu, Z.; Nogues, I.; Yao, J.; Mollura, D.; Summers, R.M. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Computer-Aided Detection: CNN Architectures, Dataset Characteristics and Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2016, 35, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, D.; Han, D.; Choi, S.; Kang, S.; Yoo, H.J. DT-CNN: An energy-efficient dilated and transposed convolutional neural network processor for region of interest based image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Papers 2020, 67, 3471–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaidat, T.; Khalil, K. A survey on neural network hardware accelerators. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 3801–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.; Goswami, D.; Halder, S.; Khalil, K.; Leray, P.; Bayoumi, M.A. Deep learning-based defect classification and detection in SEM images. In Proceedings of the Metrology, Inspection, and Process Control XXXVI, San Jose, CA, USA, 24–28 April 2022; p. PC120530Y. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, K.; Eldash, O.; Kumar, A.; Bayoumi, M. Designing novel AAD pooling in hardware for a convolutional neural network accelerator. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 2022, 30, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Lyu, Y.; Huang, X. Roadnet-rt: High throughput cnn architecture and soc design for real-time road segmentation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Papers 2020, 68, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1505.04597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, A.; Maaz, M.; Rasheed, H.; Khan, S.; Yang, M.H.; Shahbaz Khan, F. UNETR++: Delving Into Efficient and Accurate 3D Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 3377–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, C.; Wu, F.; Yang, M.; Pan, L.; Ding, W.; Dong, J.; Huang, L.; Zhuang, X. Multi-Source Domain Adaptation for Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 1640–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.R.K.; Islam, M.S.; Al-Mukhtar, M.; Porna, S.B. SAGAN: Maximizing Fairness using Semantic Attention Based Generative Adversarial Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Information Technology, Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (ICIBA), Chongqing, China, 26–28 May 2023; Volume 3, pp. 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: Redesigning Skip Connections to Exploit Multiscale Features in Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, D.; Han, J. Deep Generative Adversarial Reinforcement Learning for Semi-Supervised Segmentation of Low-Contrast and Small Objects in Medical Images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 3072–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.J.; Heinrich, M.P.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.G.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.; Riegler, M.A.; Johansen, D.; Halvorsen, P.; Johansen, H.D. DoubleU-Net: A Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 33rd International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), Rochester, MN, USA, 28–30 July 2020; pp. 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, N.K.; Jha, D.; Riegler, M.A.; Johansen, H.D.; Johansen, D.; Rittscher, J.; Halvorsen, P.; Ali, S. FANet: A Feedback Attention Network for Improved Biomedical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 9375–9388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Chen, B.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, G.; Zhang, D. DS-TransUNet: Dual Swin Transformer U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.; Ju, M.; Liu, H. MTC-TransUNet: A Multi-Scale Mixed Convolution TransUNet for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2023 16th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI), Taizhou, China, 28–30 October 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader Khan, M.R.; Samiul Islam, M.; Porna, S.B.; Alie Kamara, A.; Hossain, M.; Rafi, A.H. Adaptive Augmentation of Imbalanced Class Distribution in Road Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Electrical, Communication and Computer Engineering (ICECCE), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 30–31 December 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boink, Y.E.; Manohar, S.; Brune, C. A Partially-Learned Algorithm for Joint Photo-acoustic Reconstruction and Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, K.; Saito, D.; Shouno, H. Analysis of function of rectified linear unit used in deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Killarney, Ireland, 12–17 July 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgeldawi, E.; Sayed, A.; Galal, A.R.; Zaki, A.M. Hyperparameter Tuning for Machine Learning Algorithms Used for Arabic Sentiment Analysis. Informatics 2021, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Song, Q.; Hu, X. Auto-Keras: An Efficient Neural Architecture Search System. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1946–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeböck, P.; Orlando, J.I.; Schlegl, T.; Waldstein, S.M.; Bogunović, H.; Klimscha, S.; Langs, G.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U. Exploiting Epistemic Uncertainty of Anatomy Segmentation for Anomaly Detection in Retinal OCT. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, U.; Yendapalli, V. Binary cross entropy with deep learning technique for image classification. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng 2020, 9, 2278–3091. [Google Scholar]

- Goutte, C.; Gaussier, E. A Probabilistic Interpretation of Precision, Recall and F-Score, with Implication for Evaluation. In Advances in Information Retrieval; Losada, D.E., Fernández-Luna, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 345–359. [Google Scholar]

- Caicedo, J.C.; Goodman, A.; Karhohs, K.W.; Cimini, B.A.; Ackerman, J.; Haghighi, M.; Heng, C.; Becker, T.; Doan, M.; McQuin, C.; et al. Nucleus segmentation across imaging experiments: The 2018 Data Science Bowl. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Chen, Y.; Meng, D.; Zhang, L. Beyond a Gaussian Denoiser: Residual Learning of Deep CNN for Image Denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 3142–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, I. FAPNET: Feature Fusion with Adaptive Patch for Flood-Water Detection and Monitoring. Sensors 2022, 22, 8245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, C.; Dehghan, M.; Zaiane, O.R.; Jagersand, M. U2-Net: Going deeper with nested U-structure for salient object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 106, 107404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Li, X.; Nguyen, K.D. SeUNet-Trans: A Simple yet Effective UNet-Transformer Model for Medical Image Segmentation. arxiv 2023, arXiv:2310.09998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layers | Conv2D1 | Conv2D2 | Padding | Activation Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | (128, 128, 3) | - | - | - |

| downblock-1 | (128, 128, 8) | (128, 128, 8) | Same | ReLU |

| downblock-2 | (64, 64, 16) | (64, 64, 16) | Same | ReLU |

| downblock-3 | (32, 32, 32) | (32, 32, 32) | Same | ReLU |

| downblock-4 | (16, 16, 64) | (16, 16, 64) | Same | ReLU |

| downblock-5 | (8, 8, 128) | (8, 8, 16) | Same | ReLU |

| downblock-6 | (4, 4, 256) | (4, 4, 32) | Same | ReLU |

| middleblock | (2, 2, 512) | (2, 2, 64) | Same | ReLU |

| upblock-6 | (4, 4, 256) | (4, 4, 32) | Same | ReLU |

| upblock-5 | (8, 8, 128) | (8, 8, 16) | Same | ReLU |

| upblock-4 | (16, 16, 64) | (16, 16, 64) | Same | ReLU |

| upblock-3 | (32, 32, 32) | (32, 32, 32) | Same | ReLU |

| upblock-2 | (64, 64, 16) | (64, 64, 16) | Same | ReLU |

| upblock-1 | (128, 128, 8) | (128, 128, 8) | Same | ReLU |

| Output | (128, 128, 2) | - | - | Softmax |

| Models | MIoU | Precision | Recall | F-1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNCNN [44] | 0.897 | 0.938 | 0.926 | 0.932 |

| FAPNET [45] | 0.887 | 0.925 | 0.945 | 0.935 |

| Unet [24] | 0.910 | 0.938 | 0.943 | 0.940 |

| UNet++ [28] | 0.926 | 0.928 | 0.873 | 0.899 |

| U2Net [46] | 0.886 | 0.502 | 0.602 | 0.547 |

| seUNet-Trans-L [47] | 0.860 | 0.96 | 0.894 | 0.926 |

| seUNet-Trans-M [47] | 0.860 | 0.947 | 0.911 | 0.929 |

| seUNet-Trans-S [47] | 0.840 | 0.95 | 0.884 | 0.916 |

| FANet [32] | 0.857 | 0.922 | 0.919 | 0.920 |

| DoubleU-Net [31] | 0.841 | 0.841 | 0.641 | 0.727 |

| DS-TransUNet-L [33] | 0.861 | 0.912 | 0.938 | 0.924 |

| mA-Unet | 0.955 | 0.966 | 0.970 | 0.978 |

| Logic Utilizing | Available | Used | Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Slice LUTs | 230,400 | 1145 | 0.5% |

| Number of FFs | 460,800 | 1268 | 0.28% |

| Number of BUFs | 544 | 1 | 0.18% |

| Number of DSPs | 1728 | 96 | 5.56% |

| Number of Block RAM | 312 | 0 | 0% |

| Bonded IOB | 464 | 130 | 28.2% |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Target FPGA | Zynq UltraScale+ |

| Toolchain | Xilinx Vivado v2022.2 |

| Quantization Scheme | Fixed-point |

| Clock Frequency | 132.08 MHz |

| Power Consumption | 0.848 W |

| Latency | 3.88 s |

| Throughput | 8060.8 frames/s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kader Khan, M.R.; Mohaidat, T.; Khalil, K. A Lightweight Modified Adaptive UNet for Nucleus Segmentation. Sensors 2026, 26, 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020665

Kader Khan MR, Mohaidat T, Khalil K. A Lightweight Modified Adaptive UNet for Nucleus Segmentation. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):665. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020665

Chicago/Turabian StyleKader Khan, Md Rahat, Tamador Mohaidat, and Kasem Khalil. 2026. "A Lightweight Modified Adaptive UNet for Nucleus Segmentation" Sensors 26, no. 2: 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020665

APA StyleKader Khan, M. R., Mohaidat, T., & Khalil, K. (2026). A Lightweight Modified Adaptive UNet for Nucleus Segmentation. Sensors, 26(2), 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020665