SDN-Oriented 6G Industrial IoT Architecture Design and Application to Optimal RIS Placement and Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Motivation

1.2. Background and Open Challenges

1.3. Proposal and Main Contributions

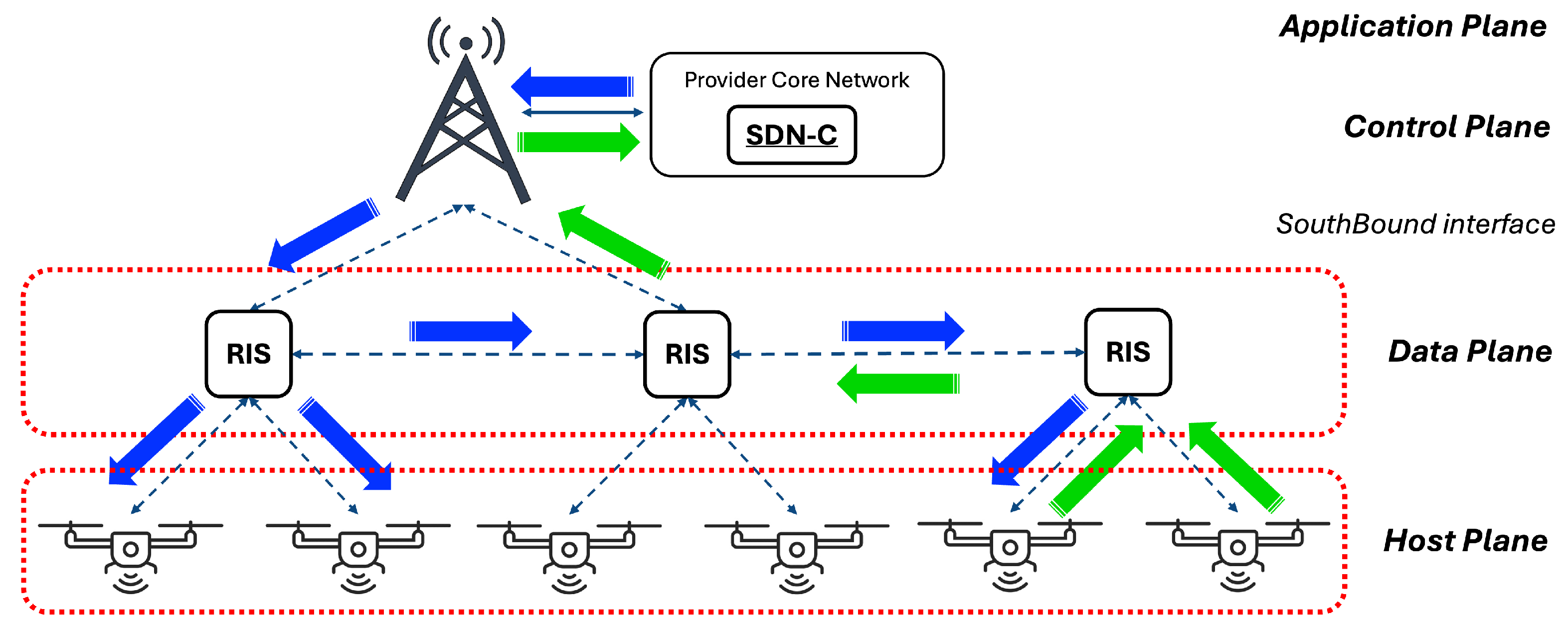

2. Proposed System Design

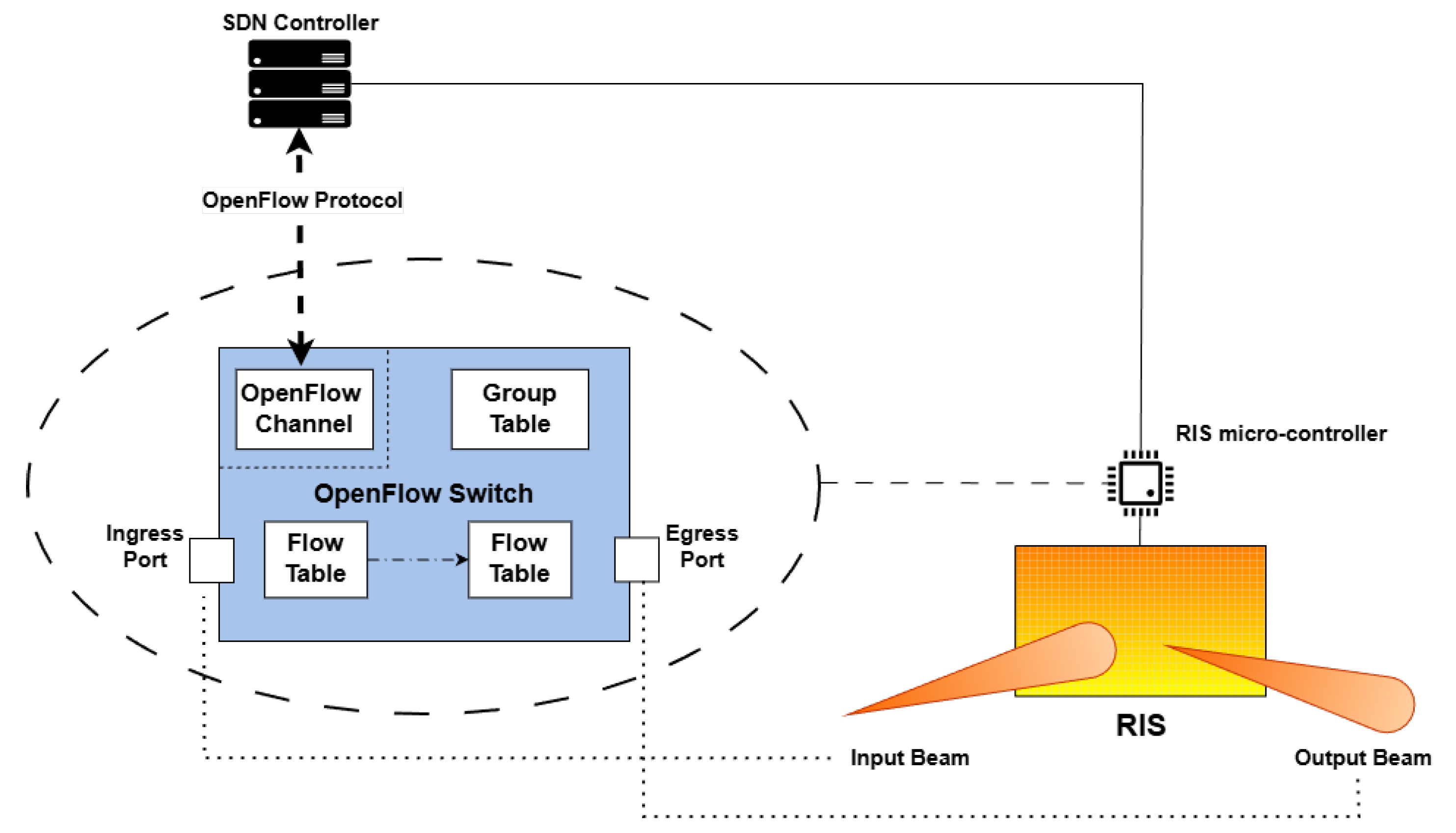

2.1. SDN-Oriented Architecture, Modules, and Interfaces

2.2. RIS Operational and Abstracted Models

- Amplifier: “The first model is the basic RIS version in which it is only required to reflect the received signal through a single output port. This enables signal redirection without phase control, but only power gain. Once the signal is received, it can be retransmitted exclusively through a predetermined fixed beam direction. Moreover, since this version has no embedded control logic, it lacks the capability to generate or initiate signals autonomously; it can only passively retransmit the signals it receives. Consequently, the network discovery phase must be initiated by gNodeB, which transmits a signal that is then reflected by the RIS elements. From a performance perspective, this model offers clear advantages in terms of simplicity, cost, and power efficiency. Its completely passive nature allows extremely low-power operation, making it attractive for large-scale deployments, where energy constraints are critical. However, these benefits come at the cost of severely limited functionality: since it is unable to modify the reflection direction, to support multi-user scenarios, or to adapt to mobility, it significantly restricts the applicability of this RIS type in dynamic wireless environments.”

- Amplifier with Phase Shifter: “In this second case, RIS is equipped with a microcontroller for beamforming control. It supports single-beam operation with a discrete phase set and functions as a multi-port hub. Once the signal is received, it may be retransmitted over a single beam and selected from a discrete set of predefined beam directions; however, only one beam can be active at any given time. This architectural model provides a remarkably wider operational set. Indeed, the ability to select a beam direction in real time improves coverage and enhances its suitability for dynamic environments. At the same time, the design remains relatively lightweight, maintaining a reasonable balance between performance, cost, and power consumption. Nevertheless, the single-beam constraint limits its effectiveness in multi-user scenarios. In this case, the network discovery protocol can be initiated by the RIS itself.”

- Multi-beam Amplifier with Phase Shifter: “This third model, which brings RIS to maturity, further extends capabilities by supporting multi-beam configurations, managed via OF Group Table mechanisms. Once the signal is received, it can be simultaneously retransmitted across multiple beams, enabling multi-directional signal propagation. This advanced model offers substantial benefits in terms of flexibility and performance. The ability to serve multiple users simultaneously and to shape the propagation environment in complex ways significantly enhances network capacity and coverage. However, these capabilities come with increased architectural complexity, higher cost, and greater power consumption, as well as a heavier reliance on synchronization and control-plane signaling between the RIS and the SDN Controller.”

2.3. Network Discovery Protocol

2.4. RIS Placement and Selection Problem

- : the set of positions of UEs to be connected;

- : the set of locations for RIS and gNB deployment;

- : the matrix of cost to connect the i-th UE with the j-th RIS (or gNodeB);

- : the decision matrix, where the element if the i-th UE is assigned to the j-th RIS (or gNodeB), and 0 otherwise.

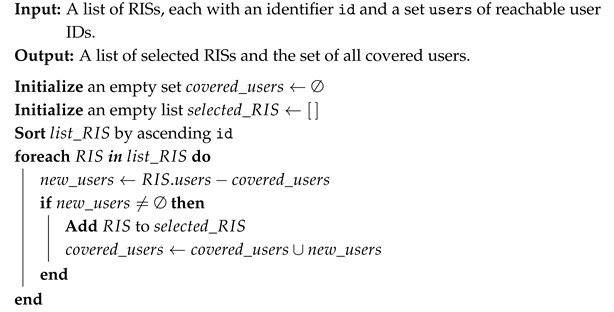

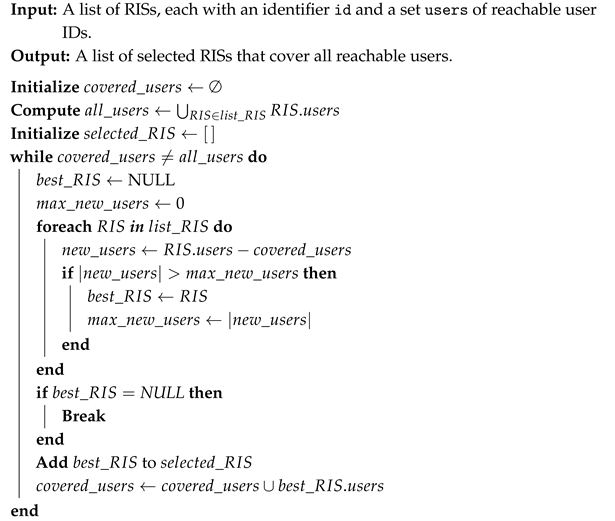

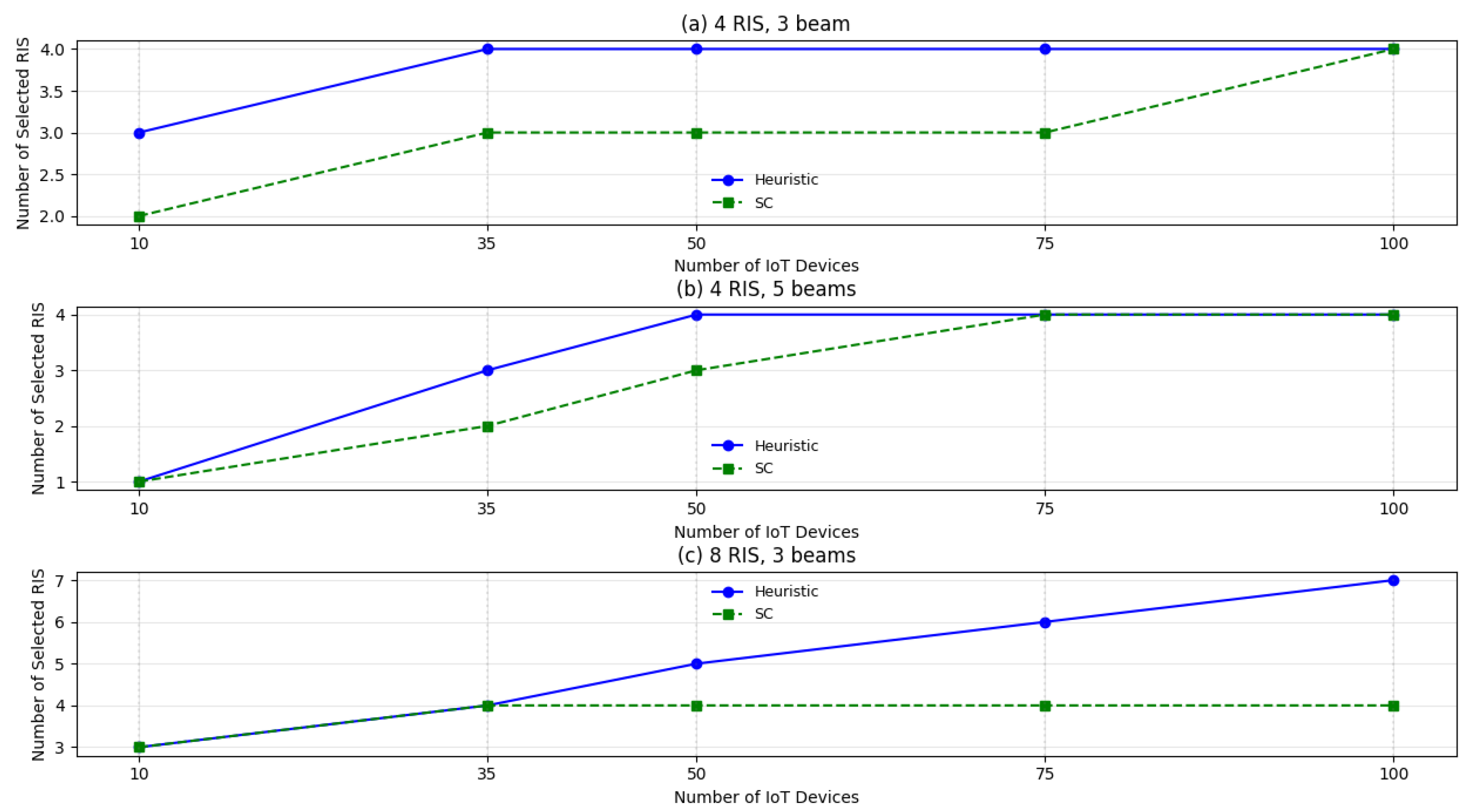

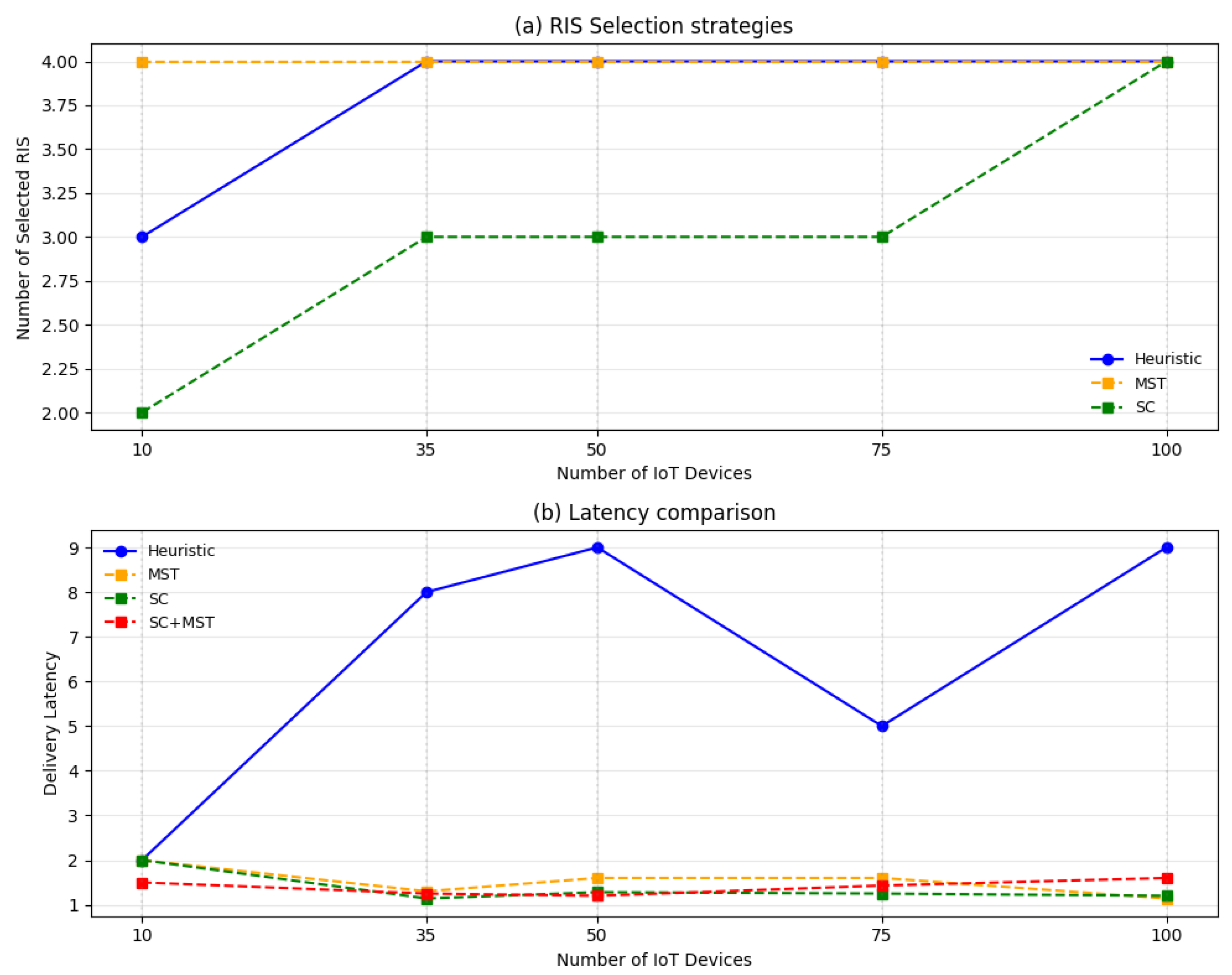

- Set Covering (SC) was explored in order to select an optimal subset of active RIS elements so that all UEs in the environment are effectively covered by at least one beam. The SC problem, in general, involves selecting the smallest number of sets from a collection such that their union includes every element in a target set. In this context, each RIS is associated with a set of UEs it can cover, and the algorithm selects the smallest subset of RISs, whose combined coverage serves all the users. This approach helps to reduce the number of RISs required, leading to a lower deployment cost, while maintaining comprehensive signal coverage.

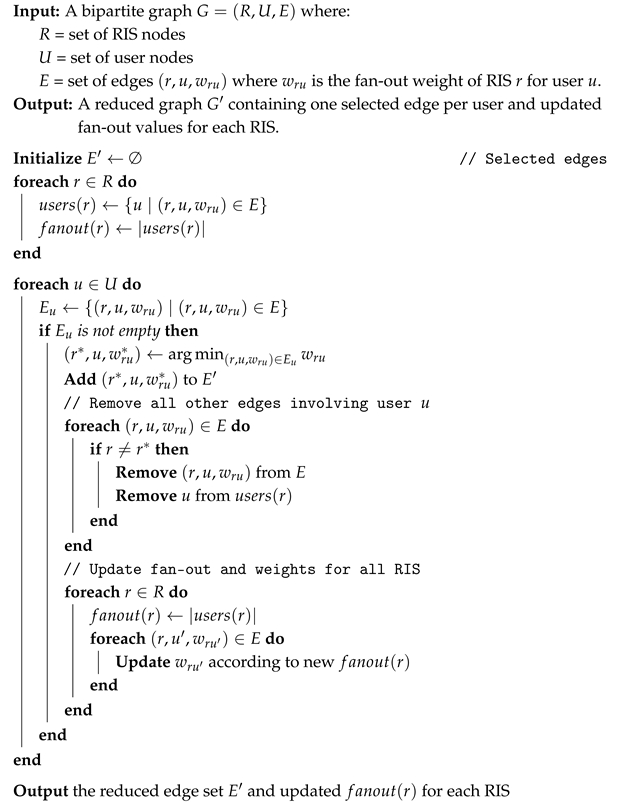

- Minimum Spanning Tree (MST) has been employed to further optimize the RIS-UE coverage, and, thus, is more related to RIS selection. In this case, the network is modeled as a weighted graph, where edges represent possible coverage links between RIS elements and UEs, and weights correspond, for instance, to the involved communications delay. The MST is then used to select a subset of these links that connect all UEs to RIS nodes with minimal overall cost, ensuring that every UE is reachable through the most efficient path traversing a set of RISs.

| Algorithm 1: Heuristic-based RIS Selection Procedure |

|

| Algorithm 2: Set Covering-based RIS Selection Procedure |

|

| Algorithm 3: MST-Based RIS Selection with Dynamic Weight Update |

|

3. Performance Evaluation

3.1. Simulation Framework Design

- Controller class is responsible for network intelligence and decision-making. It maintains the network topology and a list of connected Switch instances. Communication with the network is performed via instances of the OpenFlowChannel class, which handles the sending and receiving of control messages. Therefore, the OpenFlowChannel represents the Southbound interface between the SDN controller and RISs.

- Switch represents a programmable network node that keeps track of connected UEs (ue_reached) and nearby RIS elements (ris_reached).

- Switches can generate packets (create_packet_in), respond to feature requests from SDN Controller (create_feature_reply), and finally forward data via specific ports (send_on_ofdm_channel).

- RIS class models the RISs, storing their coordinates and beam configurations, and includes a method to determine if a device is within a beam. As mentioned before, communication between SDN Switches and the SDN Controller is handled through instances of the OpenFlowChannel class, which provides methods for sending and receiving control messages.

- UE class represents a user device and contains its position and PUCCH transmission status, with the ability to generate uplink messages (generate_pucch).

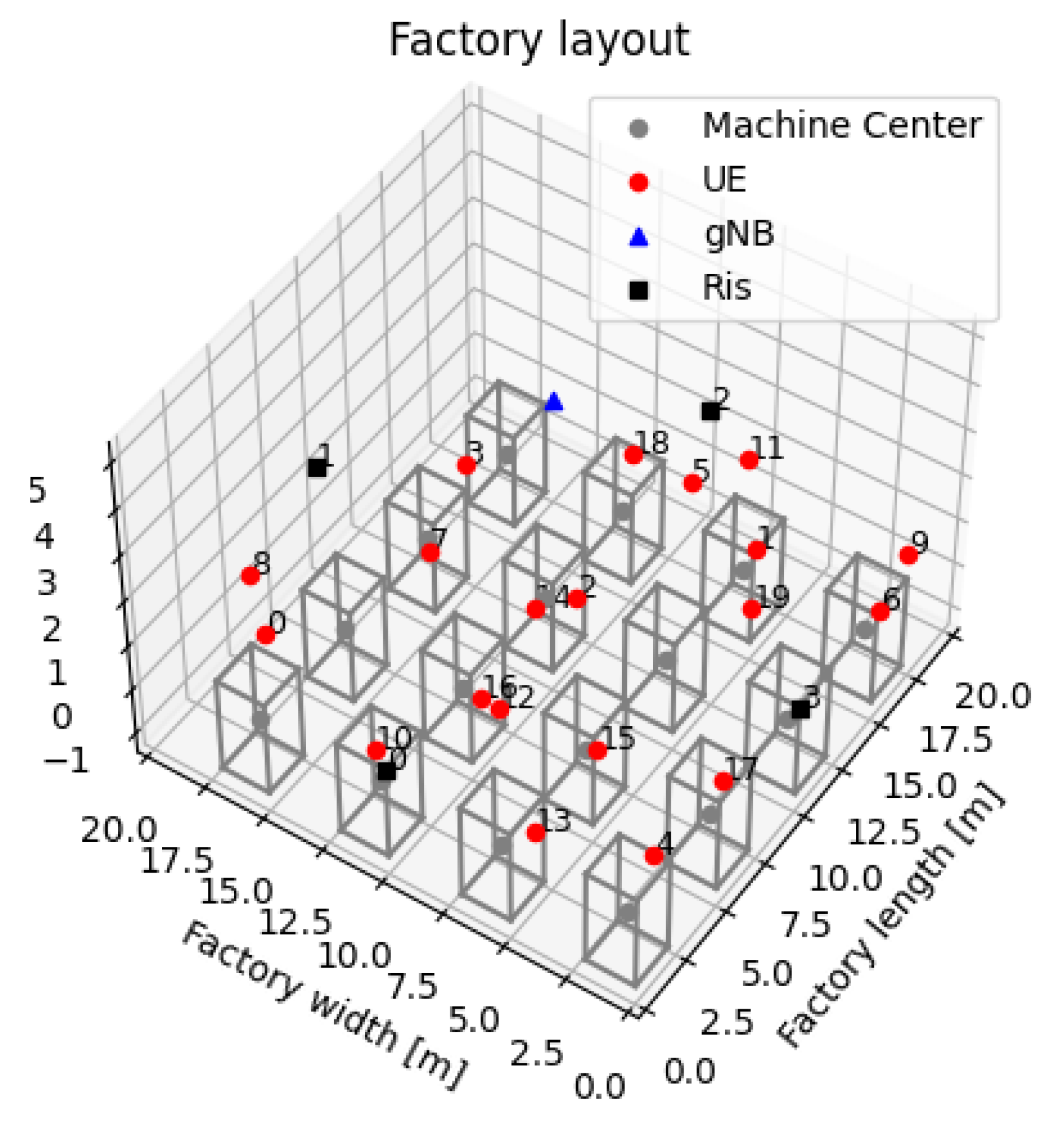

3.2. Scenarios Characterization

3.3. Numerical Results

3.3.1. Network Discovery

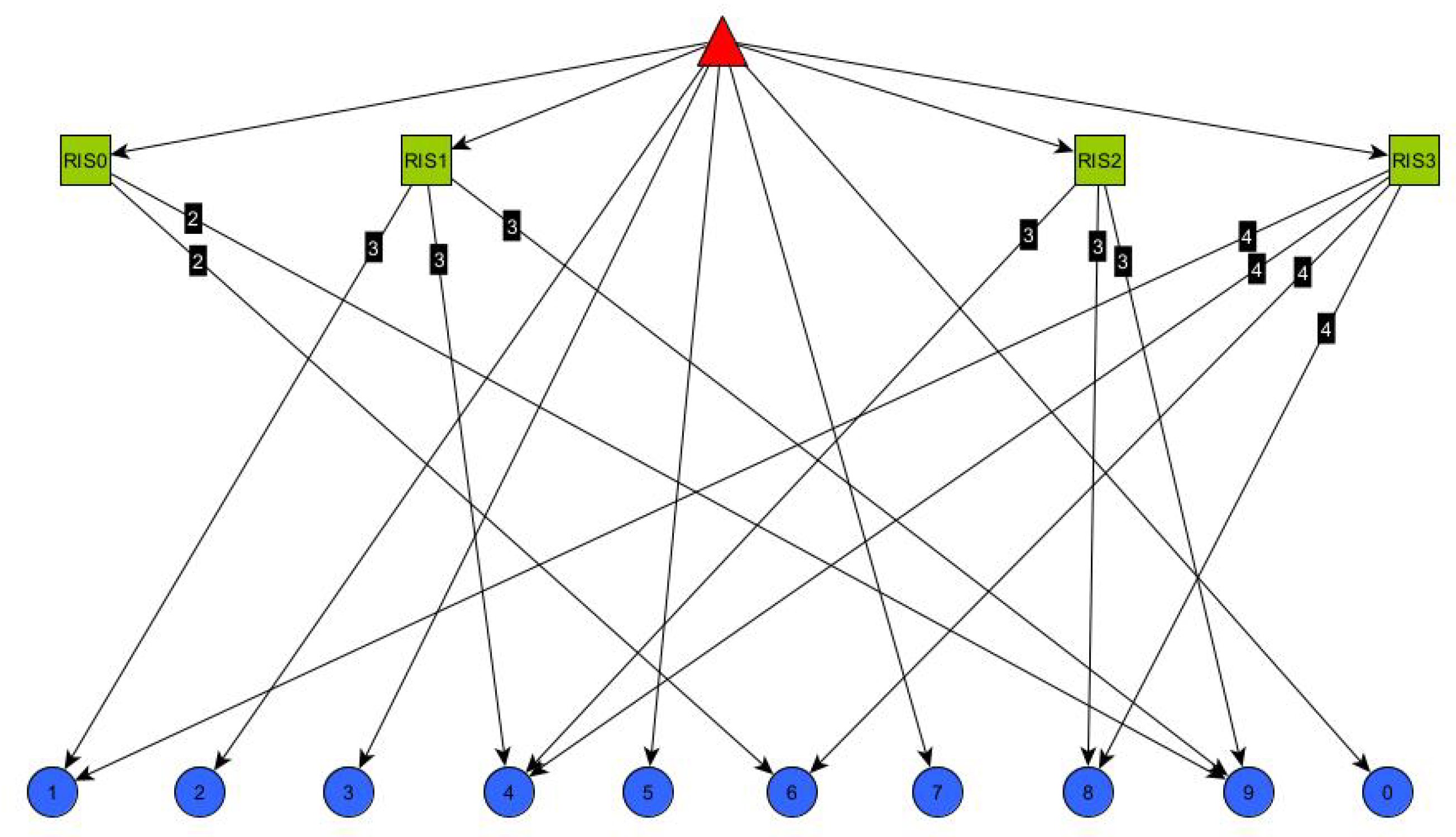

- Switch discovery: The communication process begins with the establishment of the OF session between the RIS and the SDN Controller (Figure 5a). As part of the standard OF handshake, the RIS (functioning as an OF-enabled Switch) initiates the session by sending a Hello message to the Controller. Upon receiving it, the Controller sends a Features Request message to query the RIS capabilities. The RIS responds with a Features Reply, providing essential information such as its ID and the list of available OF ports (mapped to RIS beams). This initial exchange of control messages constitutes the session setup phase, allowing the Controller to recognize and manage the RIS as part of the SDN topology.Once the session is established, the SDN Controller initiates the ND phase (Figure 5b). Leveraging the knowledge of each Switch (i.e., RIS) ports, it sends a Packet-Out message containing an LLDP packet, having previously set the RIS to broadcast it through all its active ports. Upon its reception, any Switch appends its own identifier and port information to the packet and retransmits it across its interfaces. When this message is in turn received by another RIS, it sends a Packet-In message to the Controller, including metadata about the source device. This enables the Controller to infer direct wireless links between devices and to construct an accurate view of the network topology. Figure 6 presents the resulting graph, where RIS components and all feasible links within the network are pointed out.

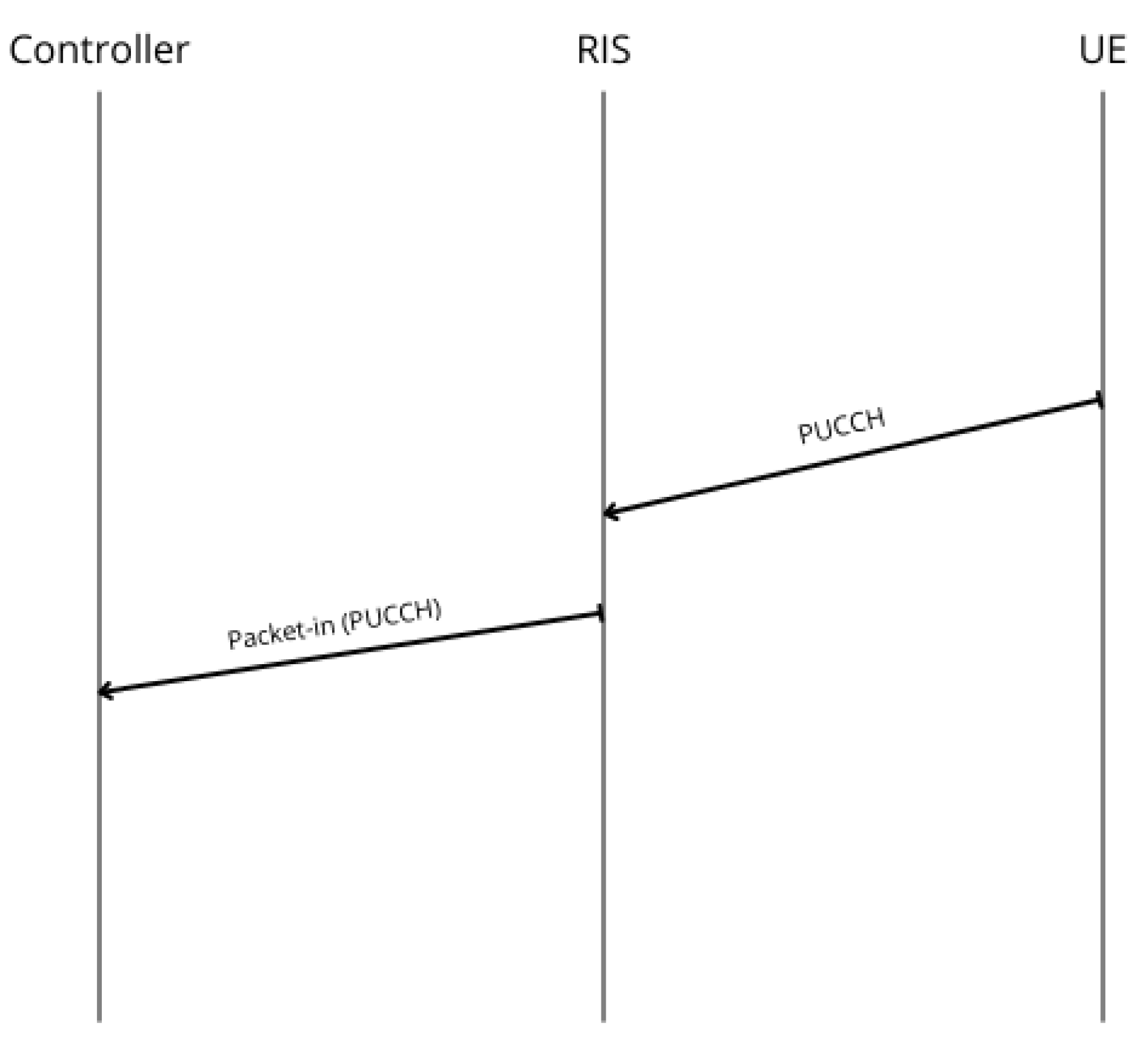

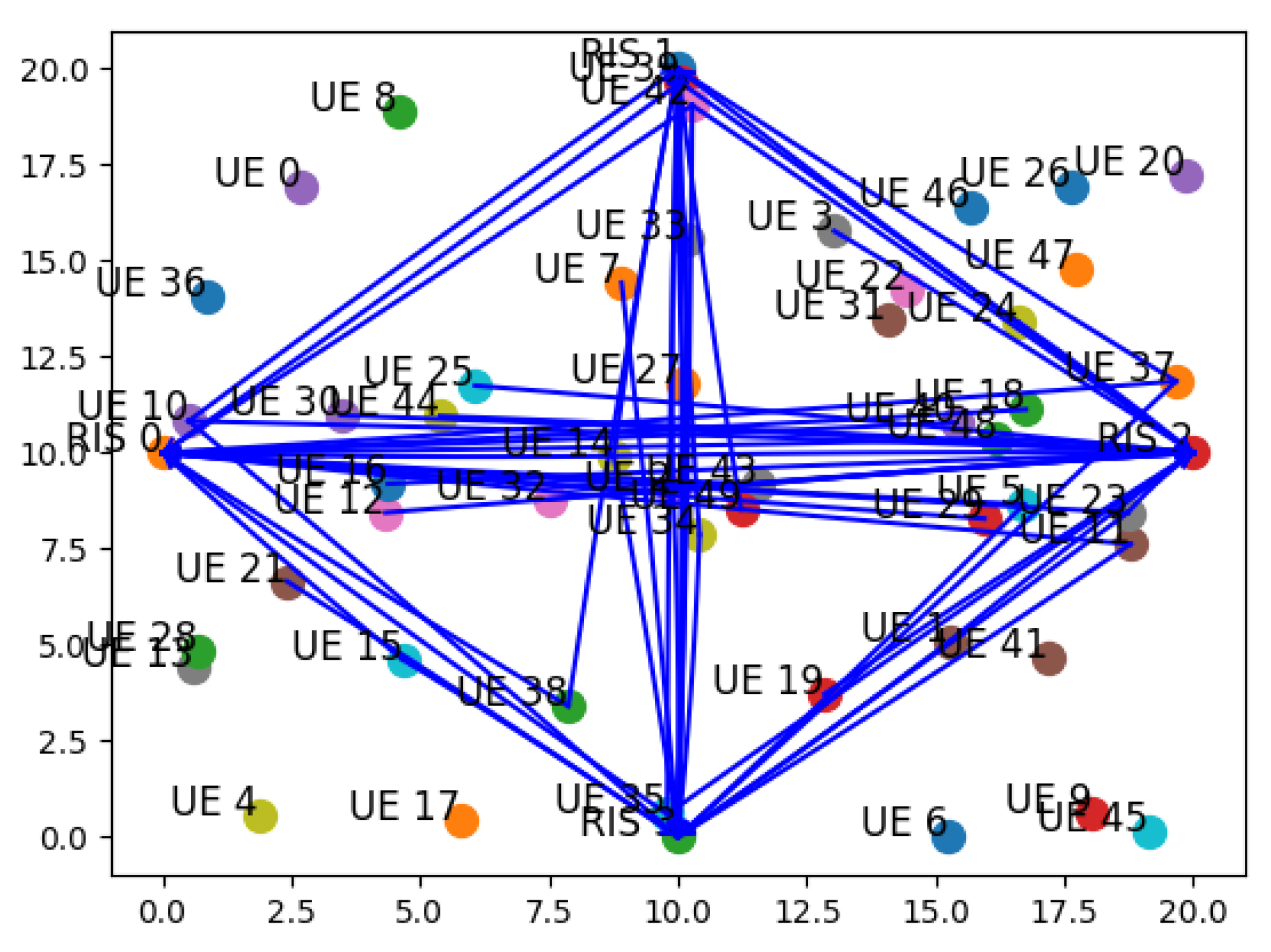

- Host discovery: Host discovery is dynamically triggered during the simulation when UE initiates communication by transmitting a PUCCH packet. For each RIS deployed in the network, it is evaluated whether the signal was received based on the RIS position and beam configuration. Each RIS that receives the signal is able to generate a Packet-In message and forwards it to the SDN Controller via the OpenFlow channel. This message contains information about the UE and the associated RIS, effectively notifying the SDN Controller of the detected link. Upon receiving this information, the Controller updates the network topology to add the discovered association between the UE and the RIS. Figure 7 illustrates the described message exchange, while Figure 8 represents all the possible links between RISs and UEs.

3.3.2. Coverage Analysis

3.3.3. RIS Placement and Selection Analysis

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, D.C.; Ding, M.; Pathirana, P.N.; Seneviratne, A.; Li, J.; Niyato, D.; Dobre, O.; Poor, H.V. 6G Internet of Things: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qamar, F.; Liaqat, M.; Hindia, M.N.; Ariffin, K.A.Z. Toward Efficient 6G IoT Networks: A Perspective on Resource Optimization Strategies, Challenges, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 76606–76633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-X.; You, X.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Haas, H.; et al. On the Road to 6G: Visions, Requirements, Key Technologies, and Testbeds. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 905–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, M.; Azari, A.; Khosravirad, S.R.; Shirvanimoghaddam, M.; Azari, M.M.; Chasaki, D.; Popovski, P. Cellular, Wide-Area, and Non-Terrestrial IoT: A Survey on 5G Advances and the Road Toward 6G. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 1117–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Okada, M. Toward 6G Internet of Things and the Convergence With RoF System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 8719–8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, D.; Munilla, J.; Khatib, E.J.; Barco, R. 5G Early Data Transmission (Rel-16): Security Review and Open Issues. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 93289–93308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liang, Y.-C.; Niyato, D. 6G Visions: Mobile ultra-broadband, super internet-of-things, and artificial intelligence. China Commun. 2019, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwis, C.D.; Kalla, A.; Pham, Q.-V.; Kumar, P.; Dev, K.; Hwang, W.-J.; Liyanage, M. Survey on 6G Frontiers: Trends, Applications, Requirements, Technologies and Future Research. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2021, 2, 836–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, M.M.; Solanki, S.; Chatzinotas, S.; Kodheli, O.; Sallouha, H.; Colpaert, A.; Montoya, J.F.M.; Pollin, S.; Haqiqatnejad, A.; Mostaani, A.; et al. Evolution of Non-Terrestrial Networks From 5G to 6G: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 2633–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, A.; Jha, R.K.; Jain, S. A Survey on Beyond 5G Network With the Advent of 6G: Architecture and Emerging Technologies. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 67512–67547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basharat, S.; Hassan, S.A.; Pervaiz, H.; Mahmood, A.; Ding, Z.; Gidlund, M. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces: Potentials, Applications, and Challenges for 6G Wireless Networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2021, 28, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tishchenko, A.; Khalily, M.; Shojaeifard, A.; Burton, F.; Björnson, E.; Renzo, M.D.; Tafazolli, R. The Emergence of Multi-Functional and Hybrid Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces for Integrated Sensing and Communications—A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 2895–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanni, M.; Chiti, F.; Pierucci, L. Hybrid Dual Stack Control Plane Design for Resilient Software-Defined WSANs. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 37853–37862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, C.; Bonanni, M.; Chiti, F.; Pierucci, L. The Alliance of SDN and MQTT for the Web of Industrial Things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 4367–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiti, F.; Degl’Innocenti, A.; Pierucci, L. Secure Networking with Software-Defined Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces. Sensors 2023, 23, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Mu, X.; Hou, T.; Xu, J.; Renzo, M.D.; Al-Dhahir, N. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces: Principles and Opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1546–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Ahmed, M.; Wahid, A.; Soofi, A.A.; Khan, W.U.; Xu, F.; Asif, M.; Han, Z. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces Enabled Vehicular Communications: A Comprehensive Survey of Recent Advances and Future Challenges. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2025, 10, 4191–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.; Singh, R.; Li, M.; Luo, H.; Dayarathna, S.; Senanayake, R.; An, X.; Stirling-Gallacher, R.A.; Shin, W.; Renzo, M.D. Integrated Sensing and Communications for IoT: Synergies with Key 6G Technology Enablers. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2024, 7, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiti, F.; Fantacci, R.; Loreti, M.; Pugliese, R. Context-aware wireless mobile autonomic computing and communications: Research trends and emerging applications. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2016, 23, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaskos, C.; Mamatas, L.; Pourdamghani, A.; Tsioliaridou, A.; Ioannidis, S.; Pitsillides, A.; Schmid, S.; Akyildiz, I.F. Software-Defined Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces: From Theory to End-to-End Implementation. Proc. IEEE 2022, 110, 1466–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.E.; Rezaei, H.; Yammine, G.; Heusinger, P.; Wu, Y.; Gerstacker, W.; Schober, R.; Franke, N.; Neumann, N. Design Considerations and Propagation Properties Using an SDN-Controlled RIS for Wireless Backhauling. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2025, 73, 2451–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cen, N. O-AAV: Programmable Software-Defined Optical Wireless Communication AAV Networking Testbed. IEEE Trans. Netw. 2025, 33, 2306–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Kamran, R.; Jha, P.; Karandikar, A. Applying SDN to Mobile Networks: A New Perspective for 6G Architecture. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2307.05924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 802.1AB-2016; Standard for Local and Metropolitan Area Networks: Station and Media Access Control Connectivity Discovery. IEEE Standards Association: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016.

- Bazan, O.; Jaseemuddin, M. Optimal antenna placement in multi-hop wireless networks with heterogeneous antennas. In Proceedings of the 2011 7th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference, Istanbul, Turkey, 4–8 July 2011; pp. 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Liang, W.; Zheng, M.; Sharif, H. A Connectivity-Aware Approximation Algorithm for Relay Node Placement in Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value/Range |

|---|---|

| Scenario size | [m3] |

| Number of gNodeB | 1 |

| Number of UEs | 10–100 |

| Number of RIS | 4–8 |

| Obstacles | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chiti, F.; Lotti, M.; Picchioni, S.; Pierucci, L. SDN-Oriented 6G Industrial IoT Architecture Design and Application to Optimal RIS Placement and Selection. Sensors 2026, 26, 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020411

Chiti F, Lotti M, Picchioni S, Pierucci L. SDN-Oriented 6G Industrial IoT Architecture Design and Application to Optimal RIS Placement and Selection. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):411. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020411

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiti, Francesco, Matteo Lotti, Sara Picchioni, and Laura Pierucci. 2026. "SDN-Oriented 6G Industrial IoT Architecture Design and Application to Optimal RIS Placement and Selection" Sensors 26, no. 2: 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020411

APA StyleChiti, F., Lotti, M., Picchioni, S., & Pierucci, L. (2026). SDN-Oriented 6G Industrial IoT Architecture Design and Application to Optimal RIS Placement and Selection. Sensors, 26(2), 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020411