Aligning Computer Vision with Expert Assessment: An Adaptive Hybrid Framework for Real-Time Fatigue Assessment in Smart Manufacturing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Ergonomic Assessment Methods

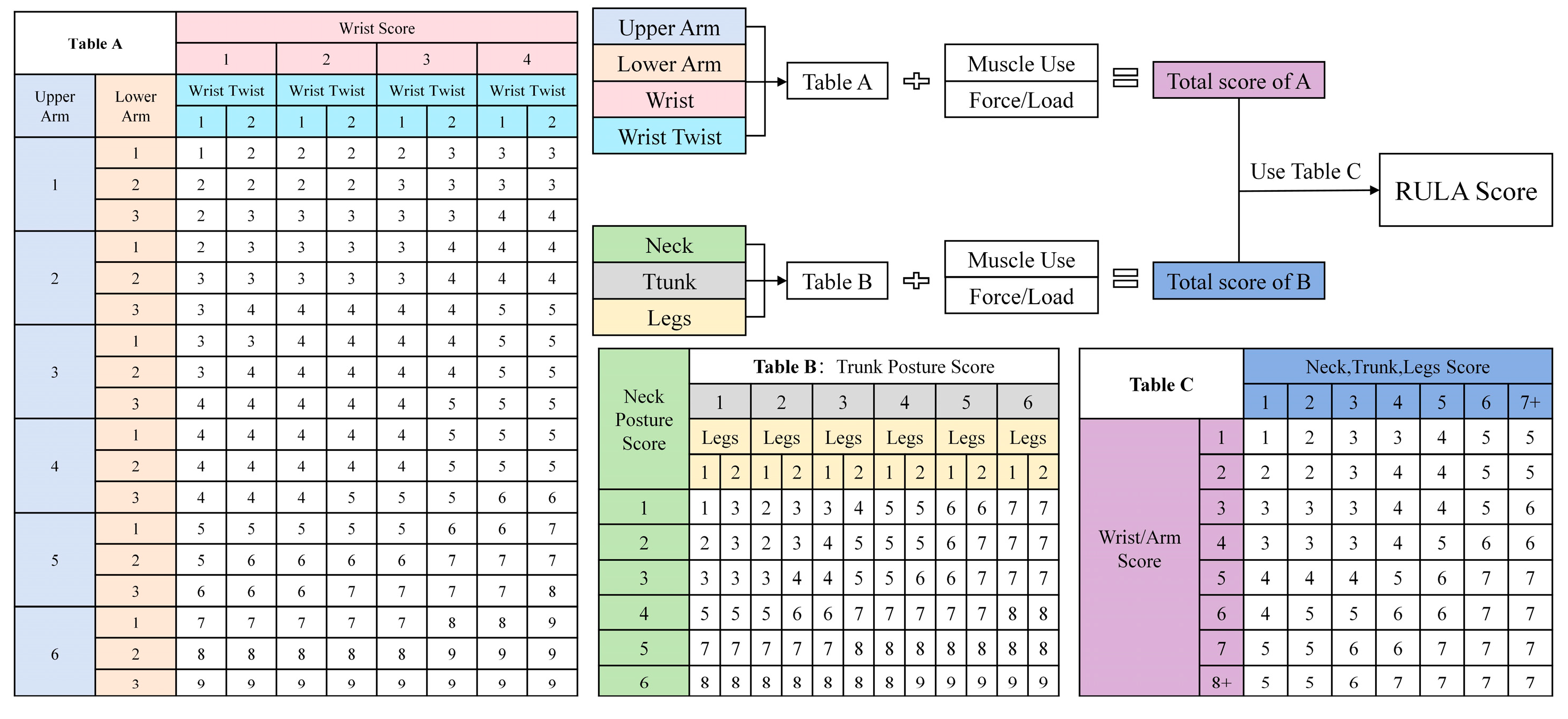

2.1.1. RULA Evaluation Method

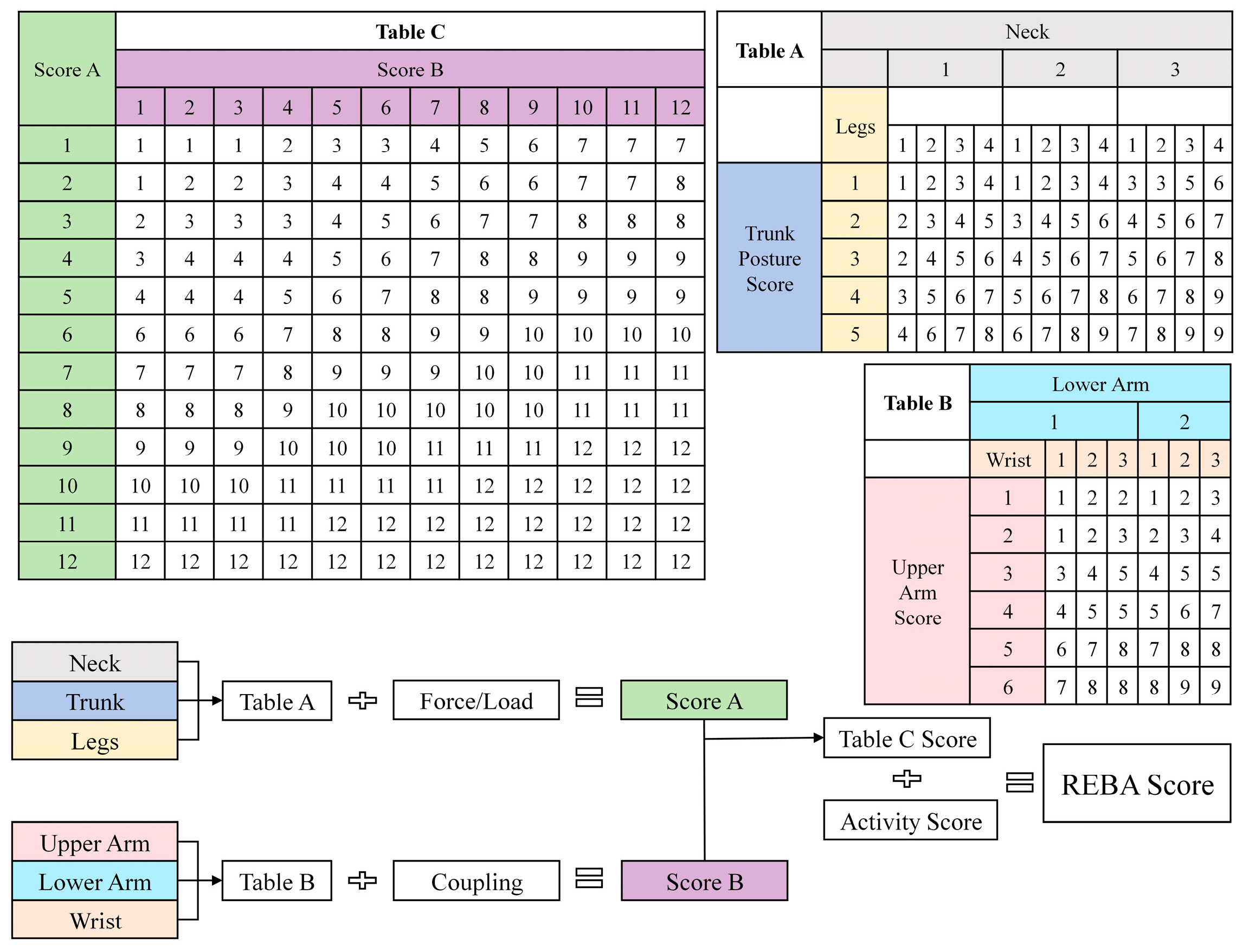

2.1.2. REBA Evaluation Method

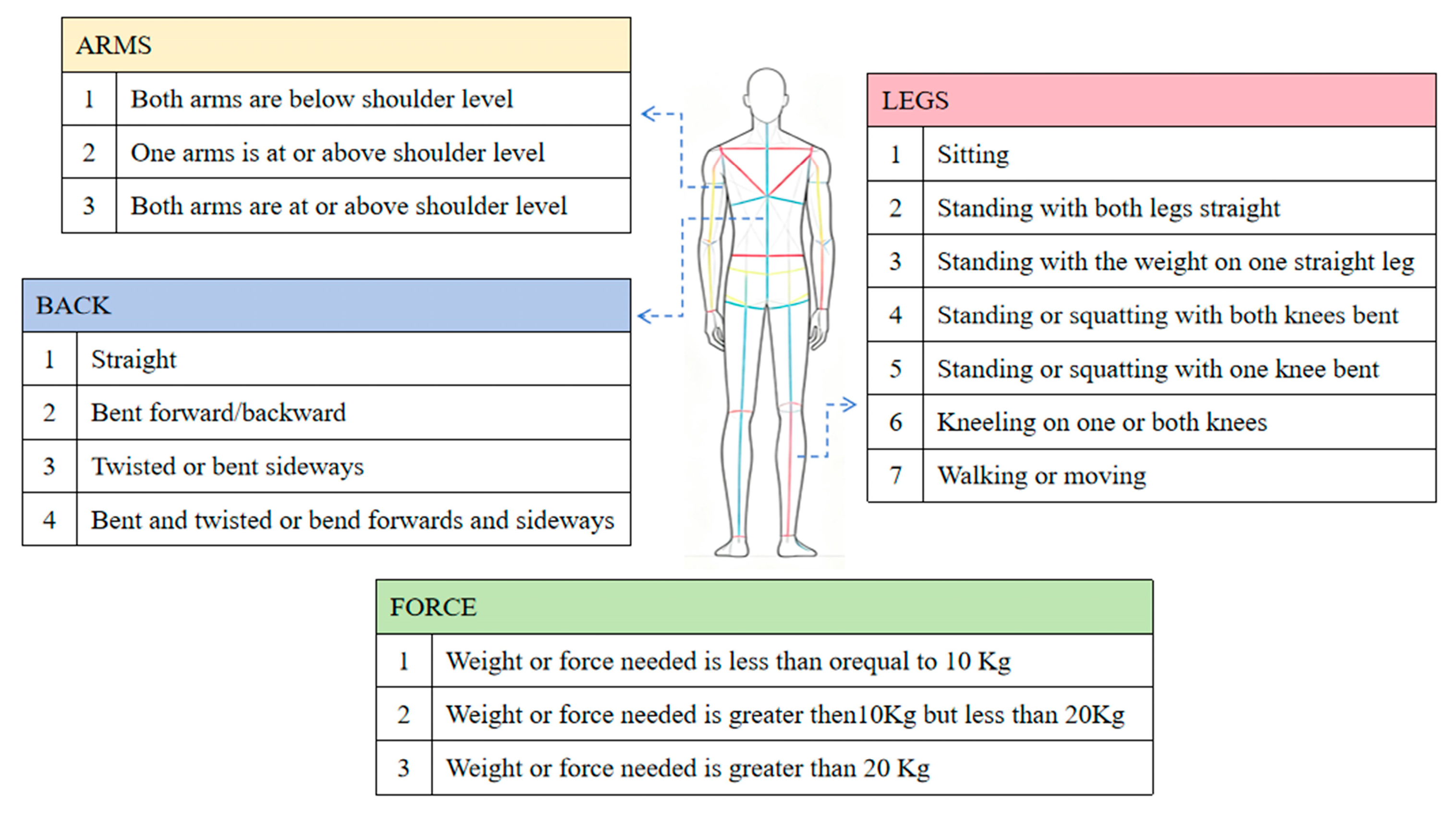

2.1.3. OWAS Evaluation Method

2.2. Ergonomic Evaluation Based on Human Posture Recognition

3. Method

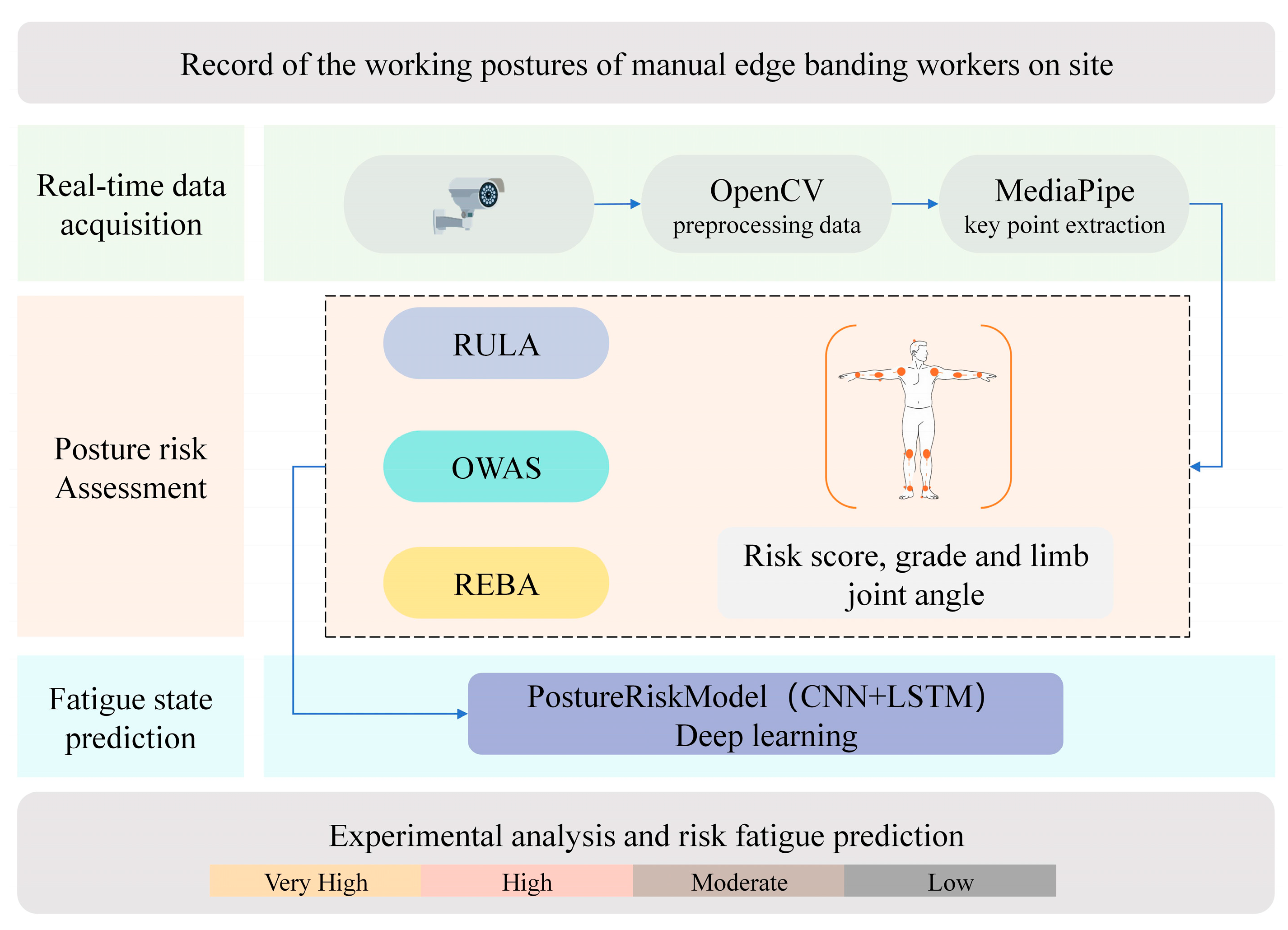

3.1. System Architecture

3.2. Limb Angle Calculation

3.3. Fatigue State Prediction Based on CNN–LSTM

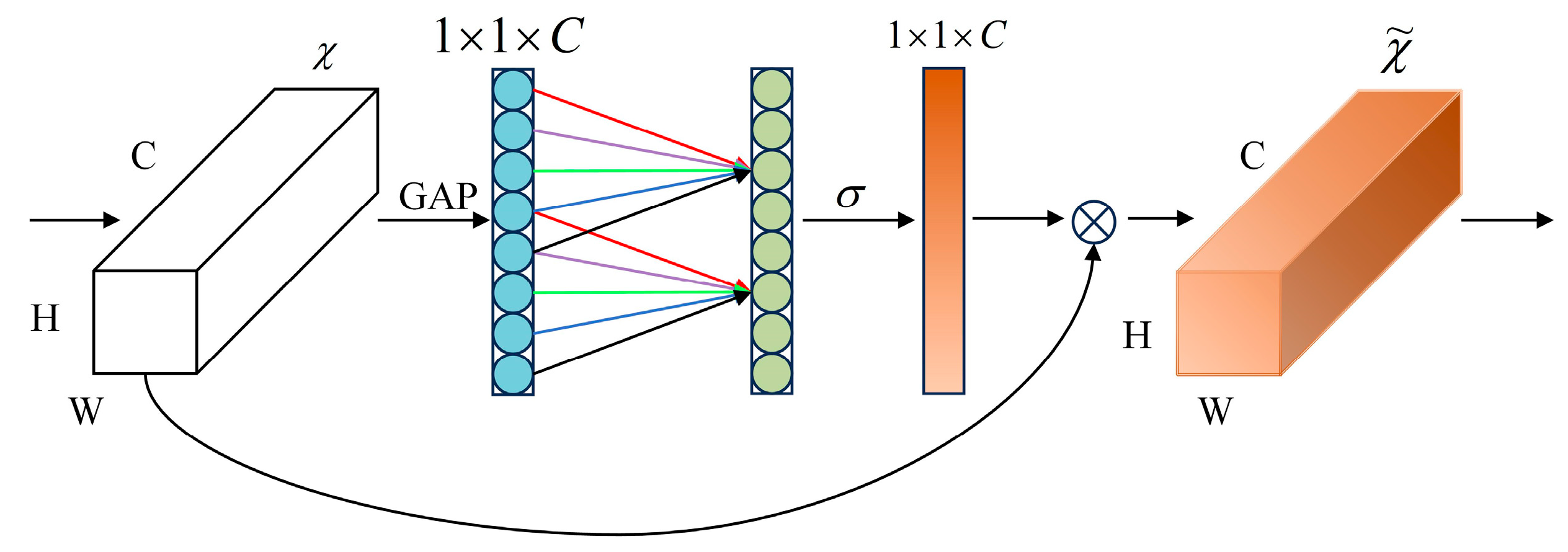

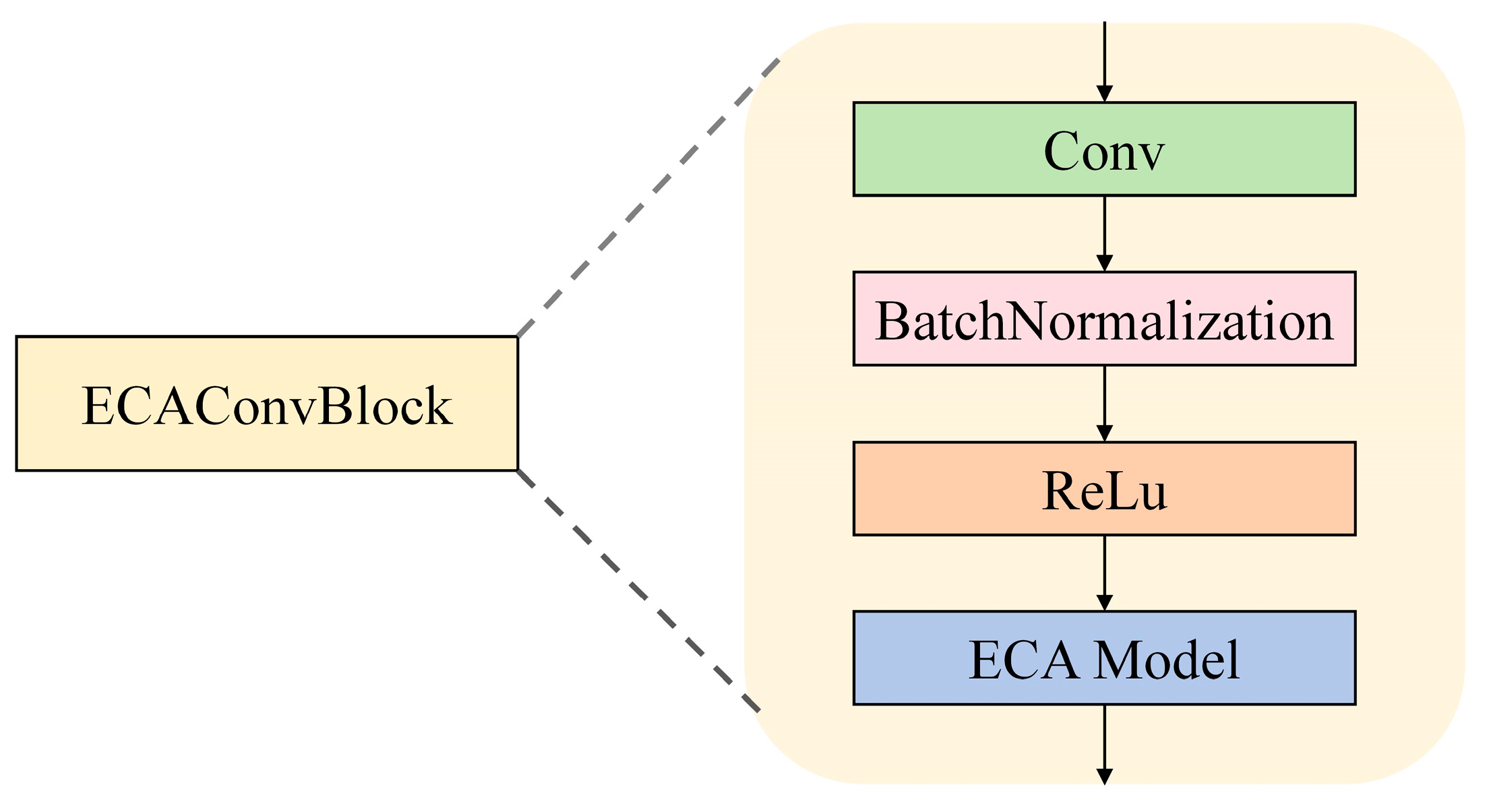

3.3.1. ECAConvBlock

3.3.2. LSTM Module

3.3.3. Concatenate

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Settings

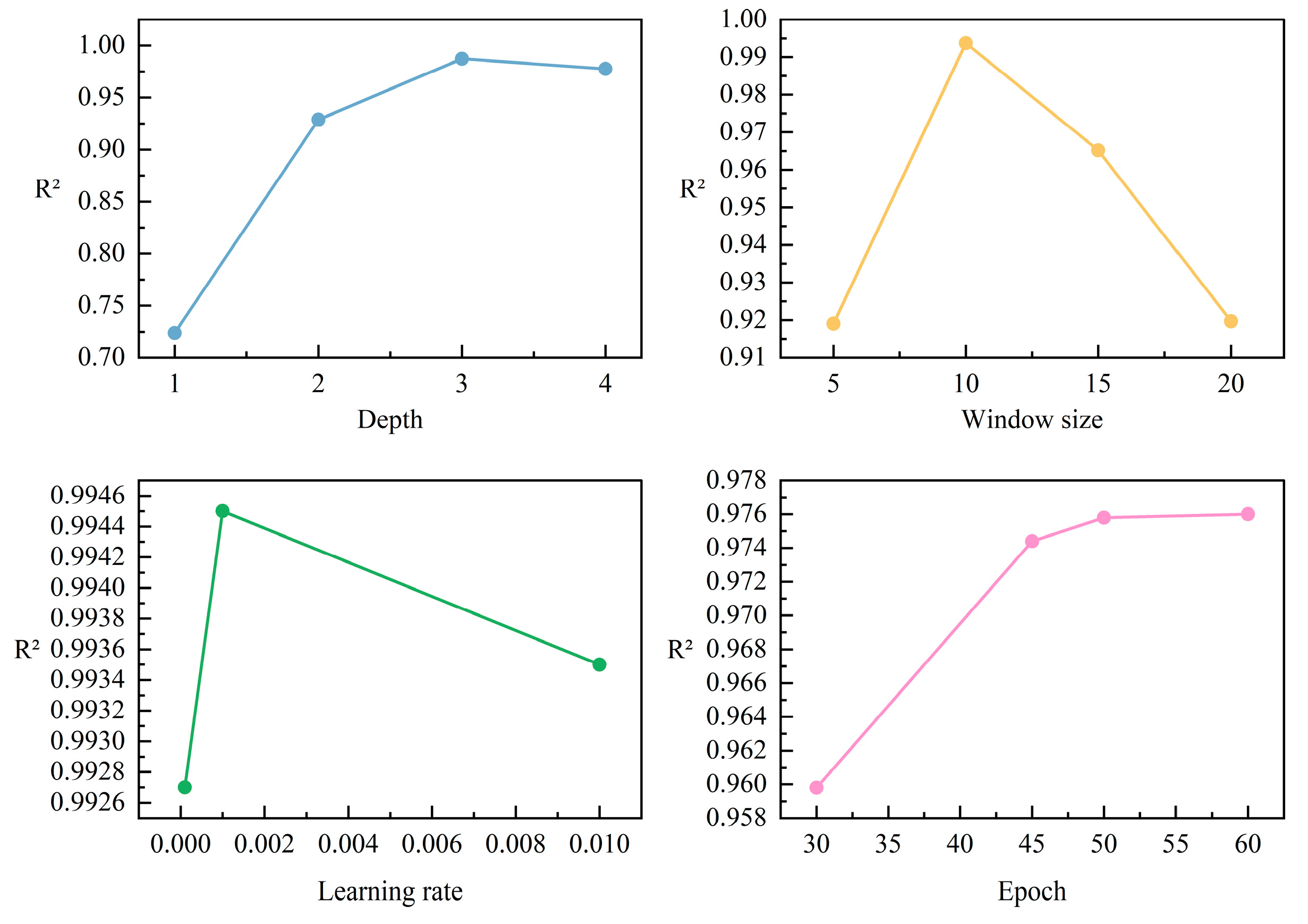

4.1.1. Details

4.1.2. Dataset

4.1.3. Evaluation Indicators

4.2. Comparative Experiment

4.3. Ablation Experiment

4.4. Real-World Scenario Results

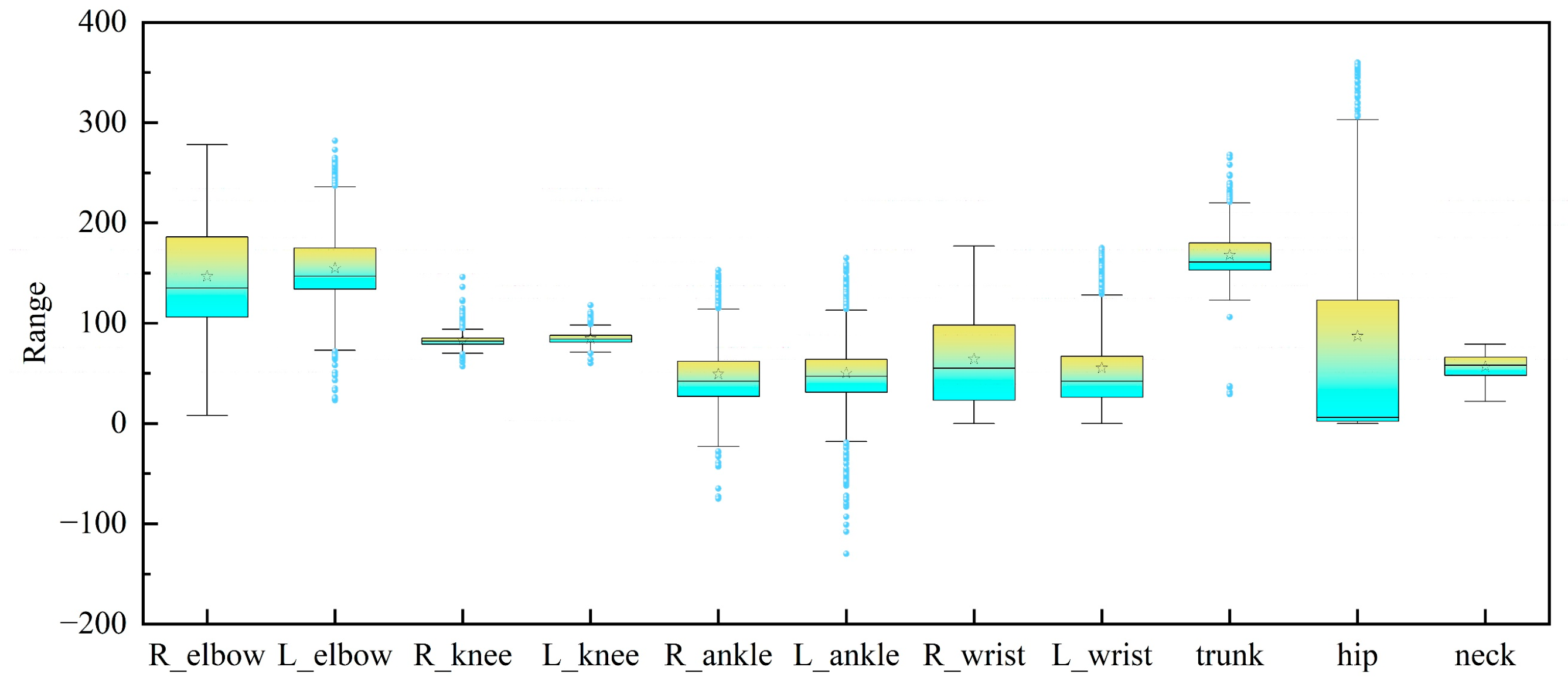

4.4.1. MediaPipe Pose Extraction Results

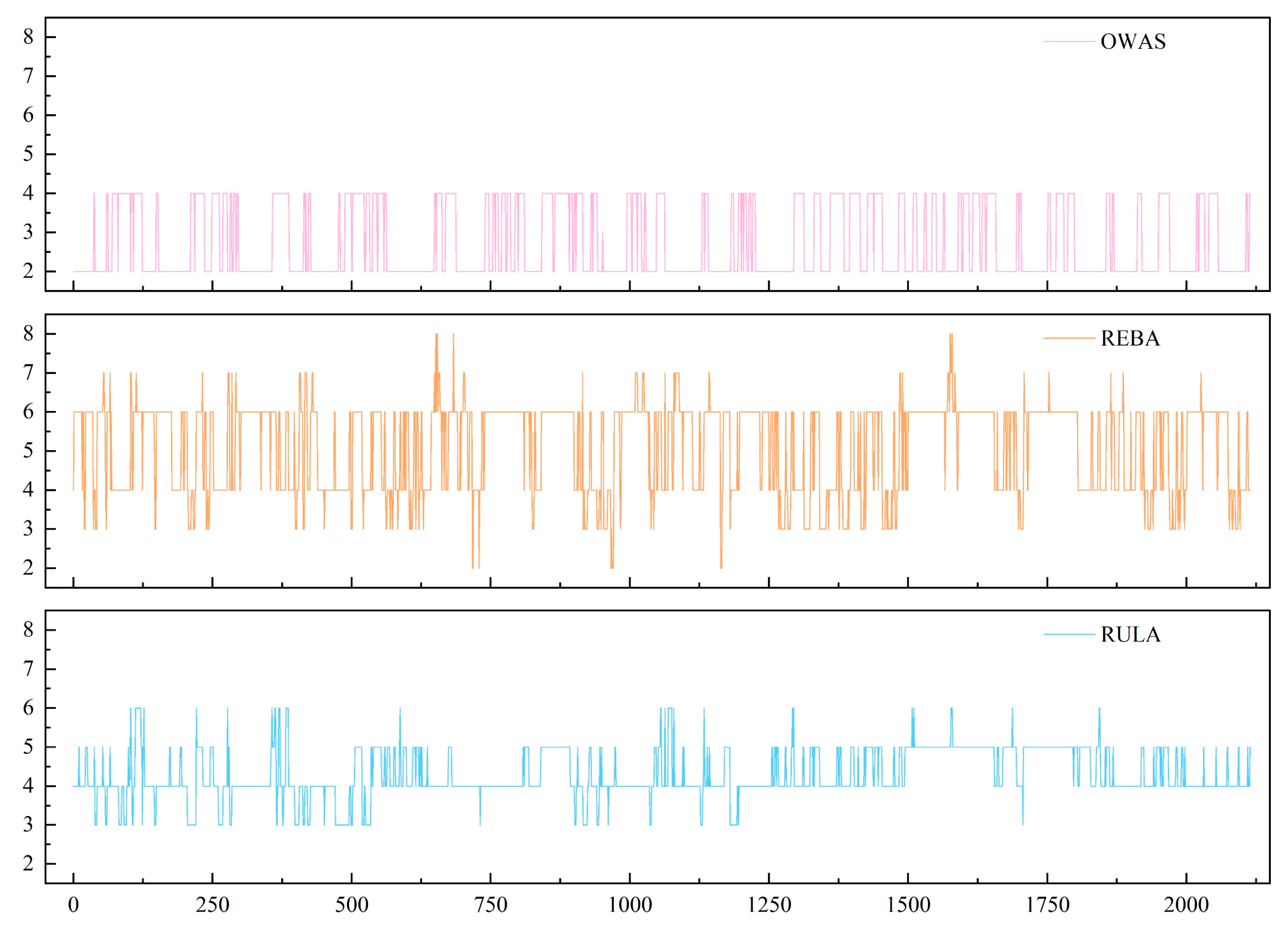

4.4.2. Expert Assessment of Consistency Validation

4.4.3. Model Prediction Results

5. Discussion

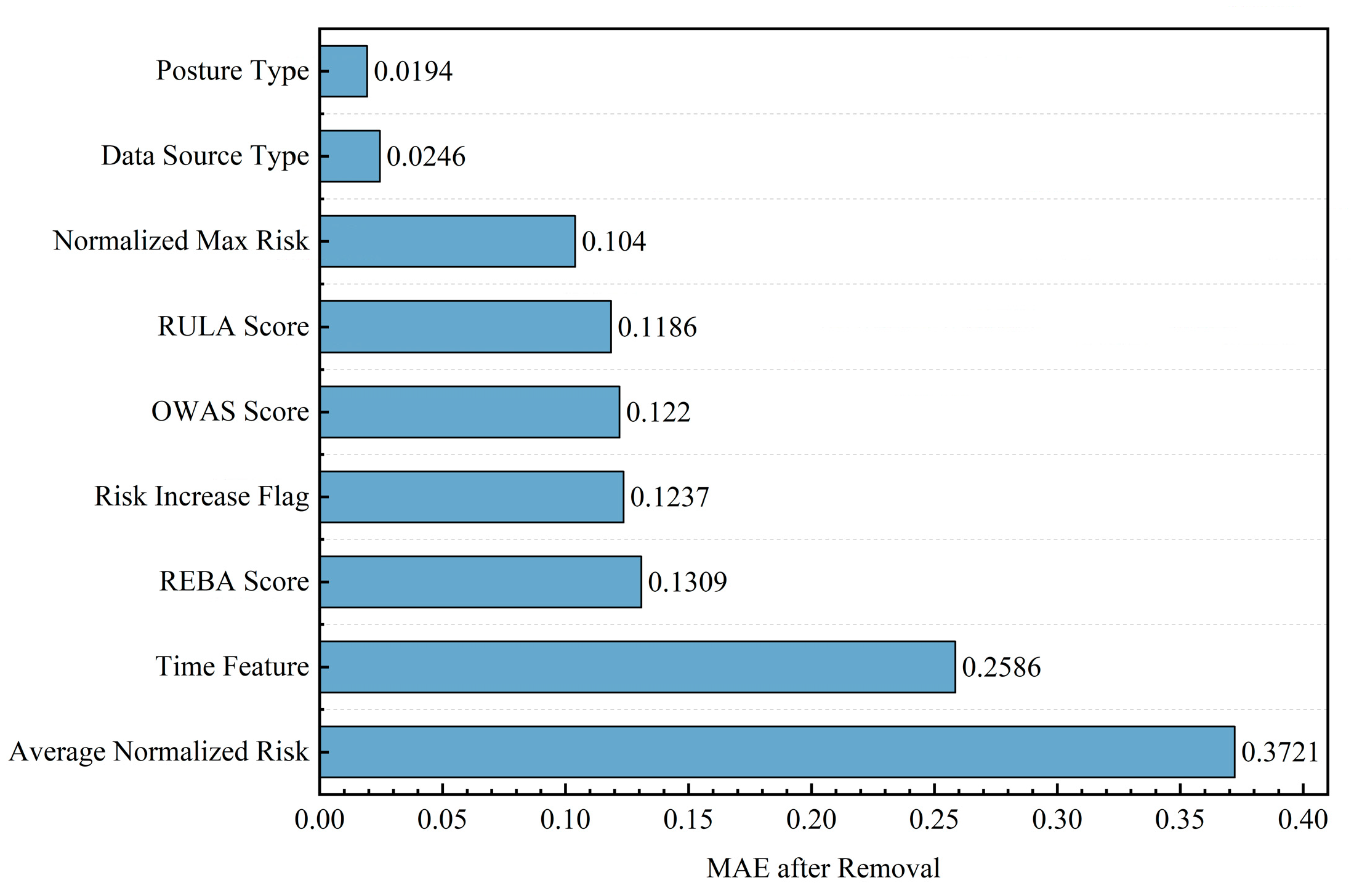

5.1. Interpretation of Feature Importance and Fatigue Mechanisms

5.2. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

5.3. Robustness Analysis: Impact of Pose Estimation Errors

5.4. Practical Implications for Smart Manufacturing

5.5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WMSDs | work-related musculoskeletal disorders |

| MSDs | musculoskeletal disorders |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| REBA | Rapid Entire Body Assessment |

| RULA | Rapid Upper Limb Assessment |

| OWAS | Ovako Working Posture Analyzing System |

| EMG | electromyography |

| sEMG | Surface Electromyography |

| PAF | Part Affinity Fields |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| HRNet | High-Resolution Net |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| ST-GCN | Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| AlexNet | Deep Convolutional Neural Network |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| SENet | Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks |

| CBAM | Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| DA | Dual Attention Network |

| ECA | Efficient Channel Attention |

| ADHD | attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| NMQ | Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire |

| IMU | inertial measurement units |

| EG | electrogoniometry |

| SVMs | Support Vector Machines |

| MSE | mean squared error |

| MAE | mean absolute error |

| R2 | R-Square |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficients |

| RPE | Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion |

References

- Jia, N.; Zhang, H.; Ling, R.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Ren, Z.; Yin, Y.; Shao, H.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, B.; et al. Epidemiological Data of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders China, 2018–2020. China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.-L. Background and significance of revision of List of International Occupational Diseases 2010 edition. Chin. J. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Dis. 2010, 28, 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Bovenzi, M.; Della Vedova, A.; Nataletti, P.; Alessandrini, B.; Poian, T. Work-related disorders of the upper limb in female workers using orbital sanders. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2005, 78, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thetkathuek, A.; Meepradit, P. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among workers in an MDF furniture factory in eastern Thailand. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2018, 24, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirka, G.A.; Smith, C.; Shivers, C.; Taylor, J. Ergonomic interventions for the furniture manufacturing industry. Part I—Lift assist devices. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2002, 29, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, N.; Wang, Z. Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorders and Their Associated Risk Factors among Furniture Manufacturing Workers in Guangdong, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.-M.; Chang, J.-H.; Indrayani, N.L.D.; Wang, C.-J. Machine learning approach to determine the decision rules in ergonomic assessment of working posture in sewing machine operators. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 87, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hignett, S.; McAtamney, L. Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA). Appl. Ergon. 2000, 31, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAtamney, L.; Nigel Corlett, E. RULA: A survey method for the investigation of work-related upper limb disorders. Appl. Ergon. 1993, 24, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhu, O.; Kansi, P.; Kuorinka, I. Correcting working postures in industry: A practical method for analysis. Appl. Ergon. 1977, 8, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kee, D. Systematic Comparison of OWAS, RULA, and REBA Based on a Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanirad, S.; Khoshakhlagh, A.H.; Habibi, E.; Zare, A.; Zeinodini, M.; Dehghani, F. Comparing the Effectiveness of Three Ergonomic Risk Assessment Methods-RULA, LUBA, and NERPA-to Predict the Upper Extremity Musculoskeletal Disorders. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 22, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Khanagar, S.B.; Alshehri, A.; Albalawi, F.; Kalagi, S.; Alghilan, M.A.; Awawdeh, M.; Iyer, K. Development and Performance of an Artificial Intelligence-Based Deep Learning Model Designed for Evaluating Dental Ergonomics. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomelleri, F.; Sbaragli, A.; Picariello, F.; Pilati, F. Digital ergonomic assessment to enhance the physical resilience of human-centric manufacturing systems in Industry 5.0. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 77, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, D.R.; Cerqueira, S.M.; Santos, C.P. Combining inertial-based ergonomic assessment with biofeedback for posture correction: A narrative review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 190, 110037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivasagam, K.; Yang, L. Evaluation of a New Simplified Inertial Sensor Method against Electrogoniometer for Measuring Wrist Motion in Occupational Studies. Sensors 2022, 22, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; D’Souza, C. A narrative review on contemporary and emerging uses of inertial sensing in occupational ergonomics. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2020, 76, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoareau, D.; Fan, X.; Abtahi, F.; Yang, L. Evaluation of In-Cloth versus On-Skin Sensors for Measuring Trunk and Upper Arm Postures and Movements. Sensors 2023, 23, 3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamsuwan, O.; Galvin, K.; Palmandez, P.; Johnson, P.W. Commonly Used Subjective Effort Scales May Not Predict Directly Measured Physical Workloads and Fatigue in Hispanic Farmworkers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalışkan, A. Detecting human activity types from 3D posture data using deep learning models. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 81, 104479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, F.; Zhao, X.; Li, W.; Wang, G. Deep feature augmentation for occluded image classification. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 111, 107737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; Bai, Q.; Yang, J.; Jiang, S.; Miao, Y. Review of Image Classification Algorithms Based on Convolutional Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.-J.; Kim, D.-H.; Son, B.-C.; Choi, K.-H.; Kwak, S.; Kim, T. A Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WMSDs) Risk-Assessment System Using a Single-View Pose Estimation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, M.; Deng, Y.; Ou, Z.; Talebian, N.; Skitmore, M.; Ge, Y. Automated Kinect-based posture evaluation method for work-related musculoskeletal disorders of construction workers. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 1731–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menanno, M.; Riccio, C.; Benedetto, V.; Gissi, F.; Savino, M.M.; Troiano, L. An Ergonomic Risk Assessment System Based on 3D Human Pose Estimation and Collaborative Robot. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gu, D.; Ke, J. Real-time ergonomic risk assessment in construction using a co-learning-powered 3D human pose estimation model. Comput.-AIDED Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2024, 39, 1337–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshev, A.; Szegedy, C. DeepPose: Human Pose Estimation via Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 1653–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Hidalgo, G.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.-E.; Sheikh, Y. OpenPose: Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation Using Part Affinity Fields. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Xiao, B.; Liu, D.; Wang, J.; Soc, I.C. Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2019), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 5686–5696. [Google Scholar]

- Bagga, E.; Yang, A. Real-Time Posture Monitoring and Risk Assessment for Manual Lifting Tasks Using MediaPipe and LSTM. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Multimedia Computing for Health and Medicine, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA; pp. 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Dai, J.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Hu, X.; Lu, T.; Lu, L.; Li, H.; et al. InternImage: Exploring Large-Scale Vision Foundation Models with Deformable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 14408–14419. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H.J.A. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2–7 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, A.; Yang, K.; Deng, J. Stacked Hourglass Networks for Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, N.N. State Minimization of Incompletely Specified Sequential Machines. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1974, 23, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Lin, D. Spatial Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bouazizi, A.; Holzbock, A.; Kressel, U.; Dietmayer, K.C.J.; Belagiannis, V.J.A. MotionMixer: MLP-based 3D Human Body Pose Forecasting. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.00499. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gers, F.A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. Learning to Forget: Continual Prediction with LSTM. Neural Comput. 2000, 12, 2451–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, L.; Yan, Y. A hybrid neural network-based intelligent body posture estimation system in sports scenes. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2024, 21, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Lu, N.; Guan, Y. Classification of Pilates Using MediaPipe and Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 77133–77140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, A.T.M.; Menon, A.S.; Reghunath, V.; Nair, J.J.; Sokakumar, A.K.A.; Jayagopal, N. Evolution of Hybrid Multi-modal Action Recognition: From DA-CNN plus Bi-GRU to EfficientNet-CNN-ViT. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition: ICPR 2024 International Workshops and Challenges, PT IV, Kolkata, India, 1 December 2024; pp. 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, C.A.C.F.; Rosa, D.C.; Miranda, P.B.C.; Si, T.; Cerri, R.; Basgalupp, M.P. Automated CNN optimization using multi-objective grammatical evolution. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 151, 111124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F.; Sufian, A.; Dutta, P. Evolution of Image Segmentation using Deep Convolutional Neural Network: A Survey. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 201, 106062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wan, Y.; Zhao, D. SFA: Efficient Attention Mechanism for Superior CNN Performance. Neural Process. Lett. 2025, 57, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Hong, C.; Xie, R.; Ran, L.; Qian, J. A simple and efficient channel MLP on token for human pose estimation. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2025, 16, 3809–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018, PT VII, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lu, H.; Soc, I.C. Dual Attention Network for Scene Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2019), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3141–3149. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2020), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 11531–11539. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Gu, M. A novel attention-guided ECA-CNN architecture for sEMG-based gait classification. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 7140–7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Xu, J. Electroencephalogram-Based ConvMixer Architecture for Recognizing Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Azam, S.; Karim, A.; Montaha, S.; Quadir, R.; Boer, F.D.; Altaf-Ul-Amin, M. Ergonomic Risk Prediction for Awkward Postures From 3D Keypoints Using Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 114497–114508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, P.; Kwon, Y.-J.; Kim, D.-H.; Choi, K.-H. Industrial Ergonomics Risk Analysis Based on 3D-Human Pose Estimation. Electronics 2022, 11, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuorinka, I.; Jonsson, B.; Kilbom, A.; Vinterberg, H.; Biering-Sørensen, F.; Andersson, G.; Jørgensen, K. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl. Ergon. 1987, 18, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Krishna Moorthy, M.; Shanmugaraja, K. Analysis of Musculoskeletal Disorder Risk in Cotton Garment Industry Workers. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20, 2162182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayvaz, O.; Ozyildirim, B.A.; Issever, H.; Oztan, G.; Atak, M.; Ozel, S. Ergonomic risk assessment of working postures of nurses working in a medical faculty hospital with REBA and RULA methods. Sci. Prog. 2023, 106, 00368504231216540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Galán, M.; González-Parra, J.-M.; Pérez-Alonso, J.; Golasi, I.; Callejón-Ferre, Á.-J. Forced Postures in Courgette Greenhouse Workers. Agronomy 2019, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.N.; Jaafar, M.H.; Mohamed, A.S.; Azraai, N.Z.; Hossain, M.S. Implementation of Kinetic and Kinematic Variables in Ergonomic Risk Assessment Using Motion Capture Simulation: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baklouti, S.; Chaker, A.; Rezgui, T.; Sahbani, A.; Bennour, S.; Laribi, M.A. A Novel IMU-Based System for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Risk Assessment. Sensors 2024, 24, 3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Kumar, S. Comparison of Ergonomic Risk Assessment Output in Four Sawmill Jobs. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2010, 16, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A.J.; Hallbeck, M.S.; Morrow, M.M.; Lowndes, B.R.; Davila, V.J.; Stone, W.M.; Money, S.R. Measuring Ergonomic Risk in Operating Surgeons by Using Wearable Technology. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiraz, A.; Gecici, A.O. Ergonomic risk assessment application based on computer vision and machine learning. J. Fac. Eng. Archit. Gazi Univ. 2024, 39, 2473–2483. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli, M.; Corradini, F.; Germani, M.; Menchi, G.; Mostarda, L.; Papetti, A.; Piangerelli, M. SPECTRE: A deep learning network for posture recognition in manufacturing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 34, 3469–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudiyanselage, S.E.; Nguyen, P.H.; Rajabi, M.S.; Akhavian, R. Automated Workers’ Ergonomic Risk Assessment in Manual Material Handling Using sEMG Wearable Sensors and Machine Learning. Electronics 2021, 10, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarevsky, V.; Grishchenko, I.; Raveendran, K.; Zhu, T.L.; Zhang, F.; Grundmann, M.J.A. BlazePose: On-device Real-time Body Pose tracking. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.10204. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J.; Yin, K.Q.; Lee, S. Automated Postural Ergonomic Assessment Using a Computer Vision-Based Posture Classification. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2016: Old and New Construction Technologies Converge in Historic San Juan, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 31 May–2 June 2016; pp. 809–818. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.-O.; Kook, J. CREBAS: Computer-Based REBA Evaluation System for Wood Manufacturers Using MediaPipe. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ishaq, M.; Swain, M.; Kwon, S. Advanced Sequence Learning Approaches for Emotion Recognition Using Speech Signals. In Intelligent Multimedia Signal Processing for Smart Ecosystems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B.J.B.; Rani, N.S.; Khan, M. Deteriorated image classification model for malayalam palm leaf manuscripts. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. Appl. Eng. Technol. 2023, 45, 4031–4049. [Google Scholar]

| Feature Category | Symbol | Range/Type | Definition/Derivation Logic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expert Scores | XRULA, XREBA, XOWAS | Int: [1, 7], [1, 15], [1, 4] | Instantaneous risk scores (corresponding to RULA Score, REBA Score, OWAS Score) derived from standard tables. |

| Avg. Norm. Risk | Float: [0, 1] | Mean of min–max-normalized expert scores over window T: | |

| Max. Norm. Risk | Float: [0, 1] | The maximum normalized risk value among the three expert scores in the current frame. | |

| Risk Trend | Binary: {0, 1} | Set to 1 if the aggregated risk score strictly increases for 3 consecutive frames; otherwise, 0. | |

| Context Metadata | Categorical/[0, 1] | Contextual metadata features: Posture Type (): encoding for camera viewpoint (front/side). Data Source Type (): ID for the capture device. Time Feature (): relative timestamp (t/T). |

| Model | MSE | MAE | R2 | Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | 0.065 | 0.147 | 0.860 | 0.23 |

| LSTM | 0.050 | 0.150 | 0.892 | 0.11 |

| CNN–LSTM | 0.033 | 0.135 | 0.924 | 0.56 |

| ECAConv–LSTM | 0.028 | 0.100 | 0.941 | 0.71 |

| Author | Dataset | Model | Guidelines | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Md. Shakhaout Hossain [55] | Human 3.6 m | DNN | REBA | Accuracy = 89.07% |

| JoonOh Seo [69] | Custom dataset | SVG | OWAS | Accuracy = 89% |

| Seong-oh Jeong [70] | Custom dataset | Mediapipe | REBA | - |

| Prabesh Paudel [56] | Human 3.6 m, COCO, MPII | YOLOv3 | RULA, REBA, OWAS | Accuracy = 92% |

| Ereena Bagga [30] | Human 3.6 m | LSTM | - | 0.9375 |

| Our research | Custom dataset | ECAConv–LSTM | RULA, REBA, OWAS | 0.941 |

| Pooling Layer | Max | Average |

|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.9232 | 0.9257 |

| Guidelines | (3,1) | Reliability Explanation | (A,1) | Reliability Explanation | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RULA | 0.807 | Good consistency | 0.894 | Good consistency | <0.001 |

| REBA | 0.862 | Good consistency | 0.886 | Good consistency | <0.001 |

| OWAS | 0.879 | Good consistency | 0.754 | Good consistency | <0.001 |

| Fatigue Level (RPE) | 0.885 | Good consistency | 0.892 | Good consistency | <0.001 |

| Guidelines | Cohen’s Kappa | Consistency Strength | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| RULA | 0.755 | Good consistency | <0.001 |

| REBA | 0.710 | Substantially consistent | <0.001 |

| OWAS | 0.768 | Good consistency | <0.001 |

| Steps | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pred. Fatigue Index | 2.24 | 1.65 | 2.06 | 1.94 | 1.68 | 2.07 | 2.24 | 3.12 |

| Fatigue index | Moderate Risk | Low Risk | Moderate Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Moderate Risk | Moderate Risk | High Risk |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, F.; Yang, Z.; Ning, J.; Wu, Z. Aligning Computer Vision with Expert Assessment: An Adaptive Hybrid Framework for Real-Time Fatigue Assessment in Smart Manufacturing. Sensors 2026, 26, 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020378

Zhang F, Yang Z, Ning J, Wu Z. Aligning Computer Vision with Expert Assessment: An Adaptive Hybrid Framework for Real-Time Fatigue Assessment in Smart Manufacturing. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020378

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Fan, Ziqian Yang, Jiachuan Ning, and Zhihui Wu. 2026. "Aligning Computer Vision with Expert Assessment: An Adaptive Hybrid Framework for Real-Time Fatigue Assessment in Smart Manufacturing" Sensors 26, no. 2: 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020378

APA StyleZhang, F., Yang, Z., Ning, J., & Wu, Z. (2026). Aligning Computer Vision with Expert Assessment: An Adaptive Hybrid Framework for Real-Time Fatigue Assessment in Smart Manufacturing. Sensors, 26(2), 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020378