1. Introduction

Millimeter-wave radar sensors have become essential components in autonomous driving sensor suites due to their all-weather robustness, direct range–velocity–angle measurement capabilities, and cost-effectiveness. Unlike camera sensors, which degrade in low-light or high-glare conditions, and LiDAR sensors, constrained by high costs, mechanical complexity, and weather sensitivity [

1], millimeter-wave radar sensors maintain stable sensing performance under adverse environmental conditions, including rain, fog, backlighting, and nighttime operation. These intrinsic sensor advantages have driven extensive research on radar-based perception systems for robust autonomous vehicle sensing [

2,

3,

4].

However, radar sensor signals inherently exhibit low spatial resolutions and lack semantic features such as shape or texture, fundamentally limiting the object discrimination capabilities. Due to these sensor-level signal characteristics, traditional radar signal processing methods such as the constant false alarm rate (CFAR) [

5] and clustering-based algorithms [

6], which rely on classical signal processing and statistical modeling, often produce high false alarm rates in cluttered environments and lack semantic representation capabilities, making them insufficient for high-level perception tasks despite their computational efficiency. To overcome these fundamental sensor limitations, multi-sensor fusion combining radar and camera has emerged as a promising approach. By exploiting the complementary sensing modalities—radar’s robust range–velocity measurement and camera’s rich semantic information—fusion frameworks enhance perception performance through cross-modal learning while maintaining all-weather operation. Vision-guided supervision and deep learning-based sensor fusion have become effective strategies, enabling radar sensing networks to learn semantic-aware representations from synchronized camera sensor data [

2,

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, cross-modal supervision alone cannot address the fundamental challenges of radar sensor signal quality variations and cross-device hardware heterogeneity.

Recent advances in deep learning have transformed radar perception from rule-based processing to data-driven paradigms. The Radar Object Detection Network (RODNet) [

2] pioneered radar object detection directly from range–azimuth (RA) maps under camera supervision, providing pixel-level cross-modal training signals. E-RODNet [

11] further improved spatiotemporal modeling through short-sequence fusion (SFF) and enhanced encoder–decoder architectures. Subsequent studies have explored radar–camera fusion and bird’s-eye-view (BEV) perception frameworks [

9,

12,

13,

14,

15], leveraging cross-modal supervision and attention mechanisms to enrich semantic understanding. Nevertheless, despite these advances, deep learning-based radar detection still suffers from two critical bottlenecks that hinder practical deployment: (1) poor cross-device generalization due to hardware-dependent signal distributions and (2) unstable temporal consistency in dynamic driving scenes.

The first issue—cross-device domain shift—occurs because radar devices differ in antenna array configuration, frequency modulation, and noise statistics. Models trained on one sensor may perform poorly on another [

16]. Although standardization-based domain adaptation techniques [

17] have shown promise, existing radar frameworks still lack systematic calibration and distribution alignment mechanisms. The second issue—insufficient temporal modeling—arises because most current radar networks use local 3D convolutions with limited receptive fields and no explicit temporal attention, leading to detection jitter and inconsistency across frames [

18].

To address these challenges, this paper proposes an improved RODNet-based radar–camera fusion framework for robust object detection. The framework synergistically integrates geometric alignment, time-division multiplexing multiple-input multiple-output (TDM-MIMO) channel calibration, chirp-wise Z-score standardization, and a lightweight GTA to tackle cross-device domain shift and temporal instability. These components work collaboratively: geometric alignment enables effective training supervision, calibration and standardization decouple hardware-specific characteristics from semantic features, and the GTA module stabilizes temporal predictions, collectively achieving robust cross-device object detection.

Experiments on the public ROD2021 dataset demonstrate that the proposed fusion framework achieves average precision of 86.32%, outperforming the baseline E-RODNet by 22.88 percentage points with only a 0.96% parameter increase. Experimental validation further demonstrates that channel calibration reduces the main lobe width by 42.3%, statistical standardization stabilizes the complex signal standard deviation to 0.037 ± 0.005, and the GTA module improves the detection performance with a minimal parameter overhead.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- 1.

A radar–camera fusion framework with improved PnP-based extrinsic calibration and closed-loop geometric verification, enabling precise cross-modal coordinate alignment for effective training supervision.

- 2.

A multi-range-bin joint TDM-MIMO channel calibration method that corrects receive-channel complex gains and transmit-phase deviations, improving cross-device array consistency.

- 3.

A chirp-wise Z-score standardization strategy with formal mathematical definitions that achieves the statistical alignment of radar signal distributions (standard deviation converging to 0.037, 99th percentile at 0.19) across sensors, enhancing model generalization and transferability.

- 4.

A lightweight GTA module that stabilizes short-term temporal features through global gating and temporal attention with only approximately 0.12 M parameters.

- 5.

Comprehensive experiments on the ROD2021 dataset and signal-level cross-device verification on AWR1642 data, validating the effectiveness of the proposed preprocessing pipeline.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work in radar preprocessing, object detection, and attention mechanisms;

Section 3 introduces the radar platform and signal modeling;

Section 4 presents the proposed methodology, including geometric alignment, channel calibration, statistical standardization, and the GTA module; and

Section 5 provides the experimental results and analysis. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the conclusions.

4. Methodology

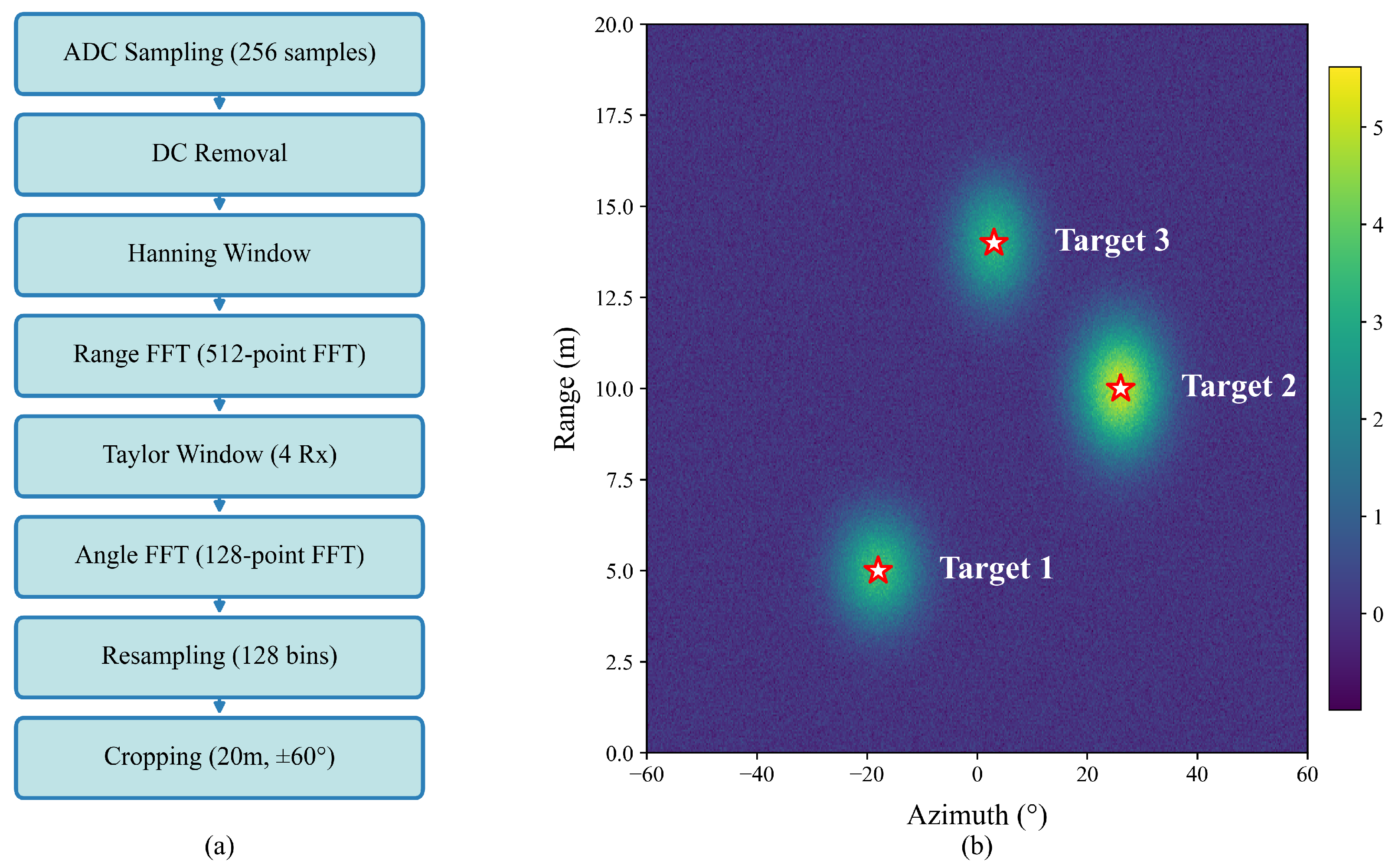

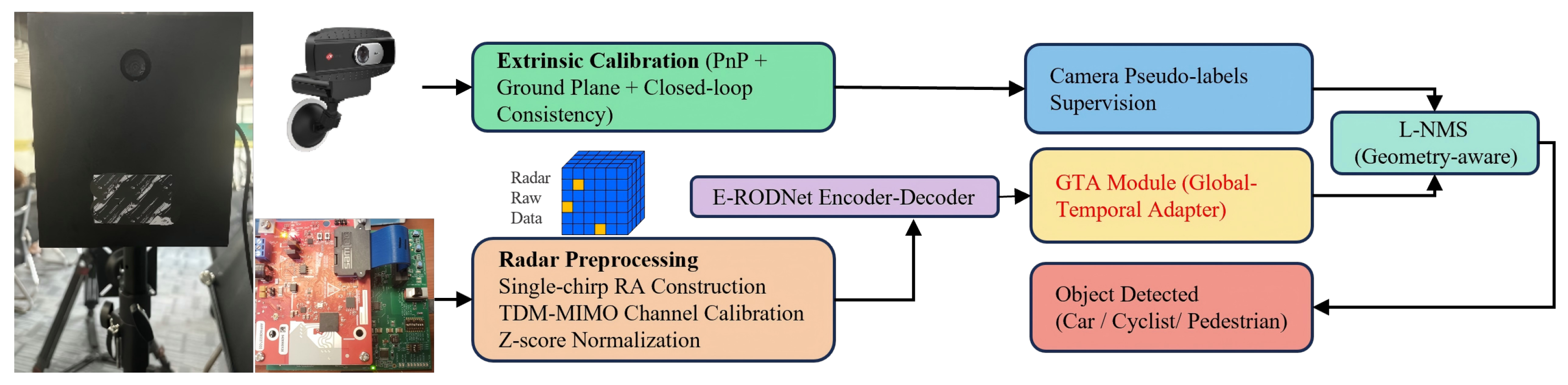

Building upon the radar platform established in

Section 3, this section presents the proposed radar–camera fusion framework for cross-device object detection. The AWR1642’s time-division multiplexing multiple-input multiple-output (TDM-MIMO) array structure requires channel calibration (

Section 4.2), while device-specific signal statistics necessitate Z-score standardization (

Section 4.3) for cross-device compatibility. The framework consists of four key components: (1) geometric alignment for radar–camera coordinate fusion, (2) TDM-MIMO channel calibration for cross-device consistency, (3) chirp-wise Z-score standardization for statistical alignment, and (4) GTA for temporal enhancement. These components enable effective cross-modal knowledge transfer from camera to radar while maintaining radar-only inference. The overall architecture is shown in

Figure 2.

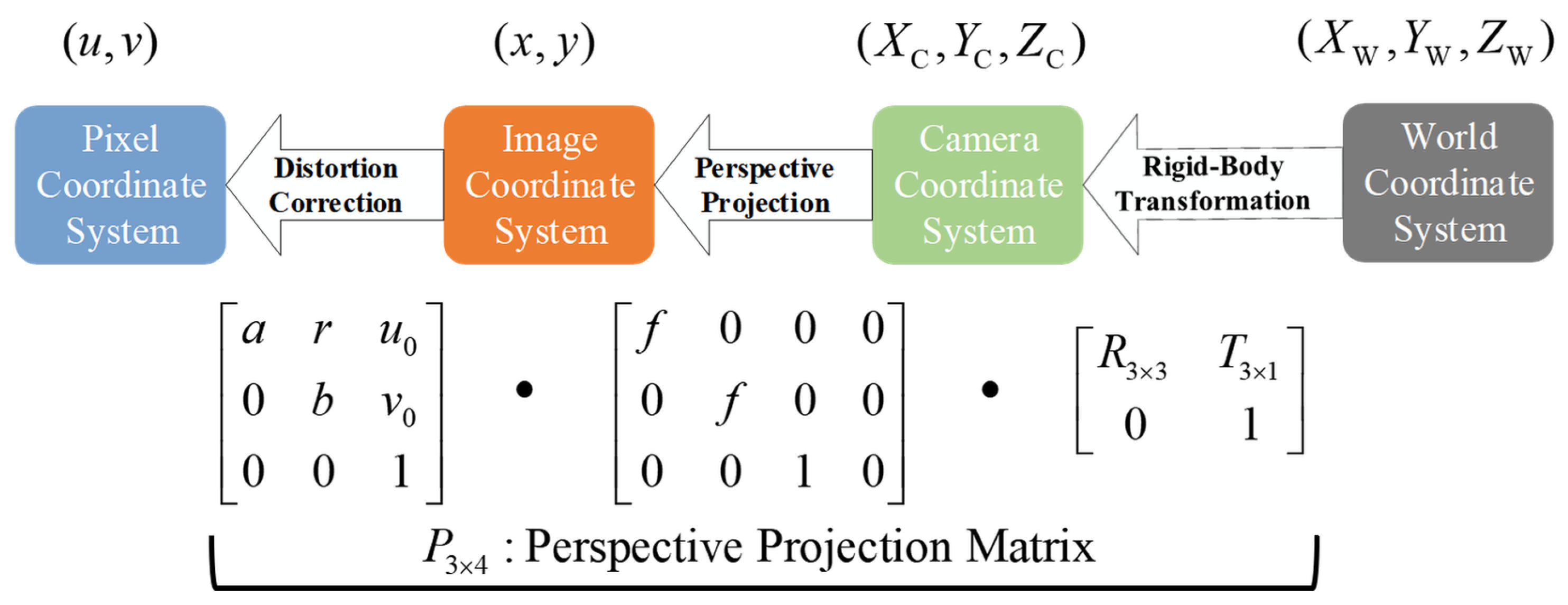

4.1. Radar–Camera Geometric Alignment for Cross-Modal Fusion

To achieve spatial consistency in radar–camera fusion, this subsection introduces the geometric alignment module that establishes precise coordinate correspondence between radar and camera. This module includes (1) coordinate system definition and extrinsic calibration via an improved PnP algorithm, (2) bidirectional projection for cross-modal mapping, and (3) closed-loop geometric consistency verification. The overall geometric relationship is shown in

Figure 3.

4.1.1. Coordinate System Definition and Extrinsic Calibration

The precise calibration of camera and radar sensors is essential for cross-modal fusion [

44]. We define a right-hand coordinate system including world

, camera

, and radar

coordinates. The radar–camera extrinsics are represented by rotation matrix

and translation vector

. Camera intrinsics are denoted by

. The transformation is

The camera uses a pinhole imaging model with distortion correction completed. Its projection is

where

s denotes the scale factor in homogeneous projection, and

denotes the perspective division that maps homogeneous coordinates to inhomogeneous pixel coordinates.

From Equations (

5) and (

6), the projection matrix is

Extrinsic calibration uses the PnP algorithm based on 2D-3D point matching. It introduces ground plane prior

(commonly

) and installation constraints such as the yaw angle, pitch angle, and camera height range to optimize solution stability. Extrinsic estimation is achieved by minimizing the reprojection error:

where

is the Huber loss function used to suppress outliers. To reduce inter-frame jitter, this paper introduces a temporal smoothing regularization term in video sequences:

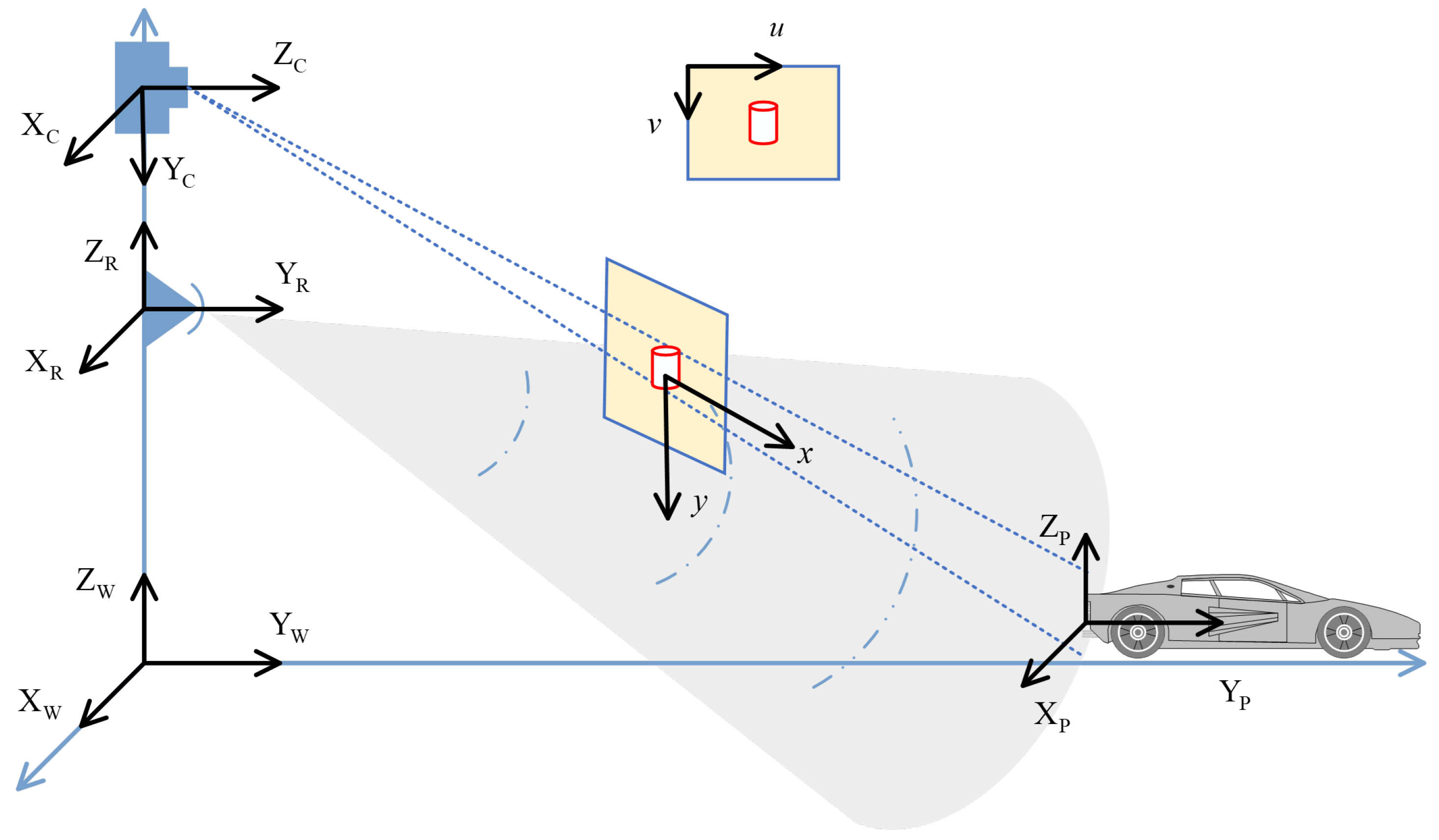

4.1.2. Bidirectional Projection and Visibility Determination

After completing extrinsic estimation, the geometric relationship between radar and camera can be established through bidirectional projection. As shown in

Figure 4, the radar range–azimuth grid

can be mapped to three-dimensional coordinates,

and the corresponding pixel coordinates can be calculated by the projection matrix

:

The inverse projection process is used to recover radar coordinates from image coordinates. For pixel point

, its normalized line-of-sight direction is

To convert image coordinates to radar coordinates , we leverage the ground plane assumption (typically for road surface). The depth estimation is constrained by this prior: the line-of-sight ray intersects the ground plane at a unique 3D point , which is then transformed to radar coordinates via . The range and azimuth are computed as and . This geometric constraint eliminates depth ambiguity for ground-plane objects.

The intersection point of the line of sight with the ground plane is mapped back to the radar frame through rigid transformation to obtain . If the projection point exceeds the image plane, satisfies , or falls into semantically invalid regions such as the sky or a car roof, the visibility mask is defined as ; otherwise, it is 1.

4.1.3. Closed-Loop Geometric Consistency Verification

To further evaluate and correct calibration errors, this paper introduces a closed-loop geometric consistency verification mechanism. For the camera detection box bottom center pixel

, the world coordinate

is obtained through back-projection and intersection with the ground plane and then projected back to the image plane through Equation (

7). The reprojection error is calculated as

If both the median error and 95% percentile error are below the threshold (such as 10 pixels), geometric consistency is considered good. Otherwise, extrinsic fine-tuning is triggered. This closed-loop error can both serve as a regularization term for extrinsic optimization and be used to automatically filter out pseudo-labels, enhancing the reliability of cross-modal supervision.

Figure 5 illustrates the closed-loop verification process.

4.2. TDM-MIMO Channel Calibration

TDM-MIMO radar uses the time-division multiplexing of transmitters combined with multiple receivers to construct a virtual array, thereby improving the angular resolution [

21]. However, phase inconsistencies between the receive channels and transmit-phase deviations can lead to distorted angle spectra, widened main lobes, and false peaks, reducing the detection accuracy and cross-device consistency. This subsection introduces a multi-range-bin joint TDM-MIMO channel calibration method to correct the receive-channel complex gains and transmit-phase deviations, improving the cross-device array consistency.

4.2.1. TDM-MIMO Virtual Array Phase Model

For a two-transmit four-receive system (AWR1642), transmitters

and

transmit sequentially in time, and each transmit is synchronized with all receivers, forming two groups of four-channel data. After merging, this forms an eight-channel virtual array:

. Let the complex gain of receive channel

n be

(where

represents the amplitude gain due to hardware mismatch and

denotes the phase offset from channel delay) and the transmit-phase deviation of transmitter

be

(representing the transmit-path phase error from TDM switching). Then, the response of virtual channel

for a target with azimuth angle

can be written as

where

represents the equivalent baseline of the virtual channel, and

. If

and

between channels or

between transmitters are inconsistent, phase coherence is destroyed, resulting in distorted angle spectra.

4.2.2. Multi-Range-Bin Joint Calibration Algorithm

To correct receive-channel complex gains and transmit-phase deviations, we propose a multi-range-bin joint calibration method. Corner reflector targets are placed at known angles, and complex echoes

from multiple range bins

k are extracted for each channel

c. The calibration parameters

are jointly optimized via least squares:

where

is the ideal steering vector,

encodes transmit-phase shifts, and ○ denotes the element-wise product. The corrected virtual array signal is

This multi-range joint approach averages out noise and multipath effects, proving more robust than single-point calibration. As shown in

Table 2, the method reduces the main lobe width by 42.3% and spurious peaks by 67.6%, significantly improving the angle spectrum clarity.

Figure 6 illustrates the calibration effect: the target becomes sharply localized with significantly reduced clutter after calibration.

4.3. Chirp-Wise Z-Score Standardization

Radar signals exhibit significant statistical variability due to hardware differences, environmental clutter, and temporal drift. To achieve cross-device statistical alignment, this paper proposes a chirp-wise Z-score standardization strategy that normalizes each chirp independently before angle FFT.

For the single-chirp range spectrum

after range FFT (where

is the range bins and

is the receive channels), standardization is applied:

where

and

are the mean and standard deviation computed separately for the real and imaginary parts of

, and

provides numerical stability. This chirp-level standardization ensures consistent statistical properties independent of the device or environment.

Experiments show that chirp-wise Z-score standardization stabilizes the complex signal standard deviation to

across all sequences and devices, with the 99th percentile at 0.19, effectively mitigating domain shift and improving model generalization.

Table 3 shows the statistical standardization results.

As shown in

Table 3, before standardization, AWR1642 exhibits Real std = 0.187 and Imag std = 0.203, significantly deviating from ROD2021’s 0.037 baseline. After chirp-wise Z-score standardization, both converge to 0.037, achieving perfect alignment with the ROD2021 reference. The amplitude P99 converges from 0.523 to 0.19, matching ROD2021 and indicating a controlled dynamic range. This statistical alignment enables cross-device generalization without distribution shift.

4.4. Global–Temporal Adapter Module

Radar object detection in dynamic driving scenarios faces temporal inconsistency challenges, where the detection results exhibit frame-to-frame jitter and false alarms due to signal noise, clutter, and insufficient temporal correlation modeling. While conventional 3D convolutions provide implicit temporal aggregation through local receptive fields, they lack explicit inter-frame dependency modeling and struggle to capture long-range temporal patterns. Transformer-based temporal attention [

24,

25] can model global dependencies but introduces quadratic complexity

and a heavy parameter overhead, limiting real-time deployment on automotive platforms.

To address these limitations, this paper proposes a lightweight GTA module with only 0.12 M parameters ( 0.96% increase over baseline E-RODNet). The GTA adopts a dual-path architecture combining global spatial gating with explicit three-frame temporal attention, achieving linear complexity

while maintaining effective temporal modeling. The global gating path adaptively recalibrates channel-wise features based on the spatial context, while the three-point temporal attention explicitly captures inter-frame correlations through efficient roll-based frame alignment. The GTA module is inserted after the SFF block in the E-RODNet baseline, where temporal features from multiple frames have been preliminarily fused but lack explicit attention-based refinement. The GTA module architecture is shown in

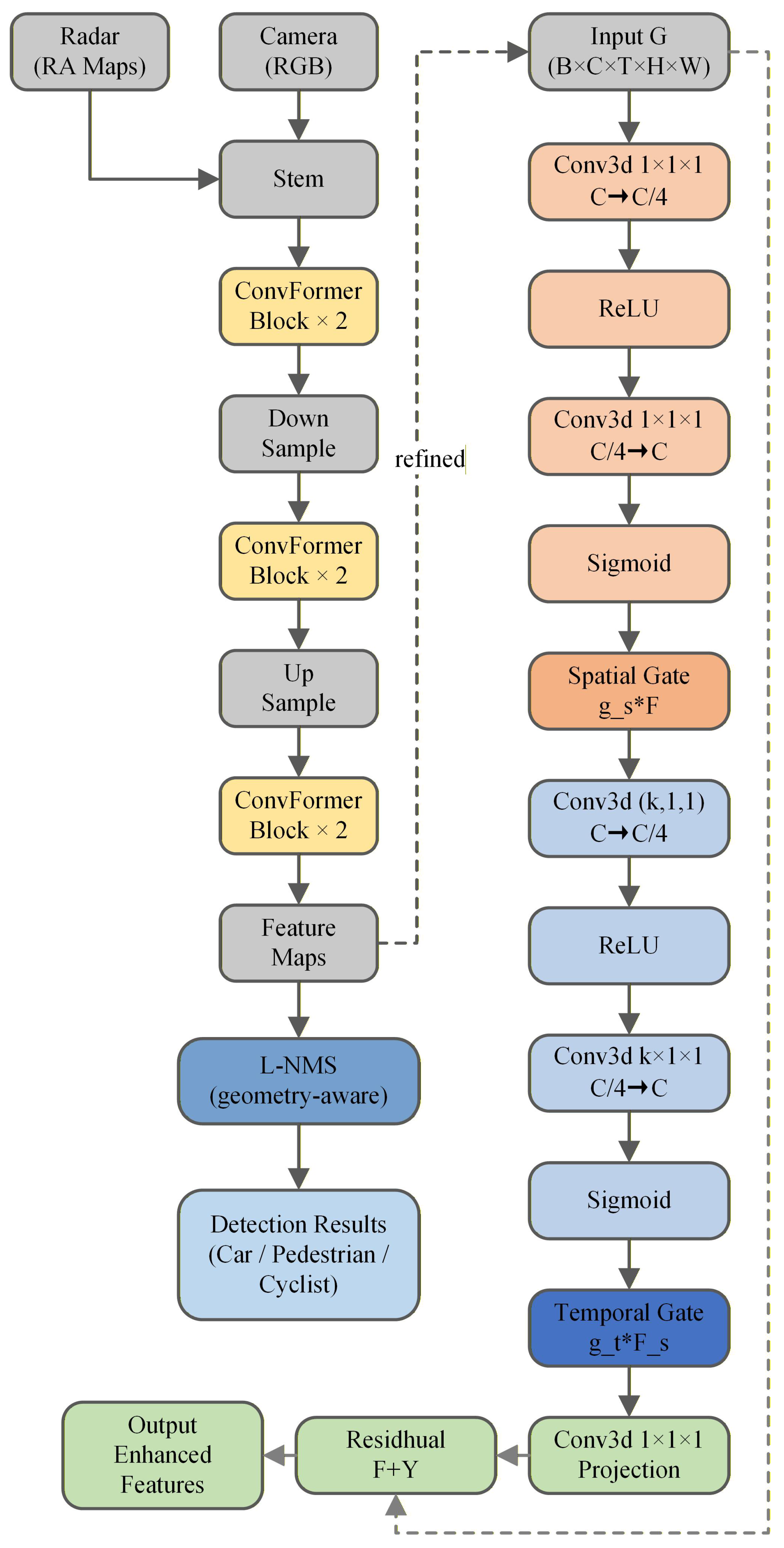

Figure 7.

4.4.1. Global Gating Mechanism

The global gating component uses global average pooling to extract the spatial context, followed by two

convolutions with ReLU activation and a sigmoid gate to produce channel-wise attention weights:

where

is the input feature map, GAP is global average pooling,

are

conv weights, and

is the sigmoid function. The gated feature is then

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication.

4.4.2. Three-Point Temporal Attention

To model temporal dependencies explicitly, the GTA module applies a three-point temporal attention mechanism. For a sequence of three consecutive frames

, features are shifted along the temporal dimension using roll operations (circular temporal shift) and then concatenated and processed by a

convolution:

where

denotes a circular shift operation along the temporal dimension by

position (similar to NumPy’s roll function), aligning adjacent frames before concatenation for temporal correlation modeling.

A Softmax operation is applied to generate temporal attention weights, which are then multiplied with the center frame to produce temporally enhanced features. This explicit three-frame attention enables the network to capture motion patterns and reduce detection jitter.

The GTA module adds only 0.12 M parameters (0.96% increase) yet significantly improves the temporal stability and detection performance.

4.5. Overall Architecture and Training Strategy

Overall architecture: As shown in

Figure 2, the framework builds upon the E-RODNet encoder–decoder architecture with GTA modules inserted after each encoder stage. GTA insertion can be controlled via a configuration file switch.

Loss function: We employ the smooth L1 loss, which provides better robustness to annotation noise compared to binary cross-entropy:

Annotation generation and post-processing: YOLOv5s generates camera pseudo-labels, which are mapped to the RA space via geometric projection. In post-processing, location-based non-maximum suppression (L-NMS) using object location similarity (OLS) suppresses duplicate detections, and person+bicycle co-occurrence identifies the cyclist category to ensure training data quality and category consistency.

4.6. Method Limitations and Design Trade-Offs

While the proposed framework addresses cross-device generalization and temporal consistency, several inherent limitations and design trade-offs require discussion. The geometric alignment module (

Section 4.1) requires accurate initial extrinsic calibration between camera and radar sensors, typically achieved through corner reflector-based procedures in controlled environments. Calibration errors propagate through the projection pipeline, affecting the pseudo-label quality. We mitigate this through closed-loop verification (

Section 4.1.3) with reprojection error thresholds, but manual calibration remains a prerequisite for deployment.

Although the GTA module adds minimal overhead (0.96% parameters, 0.59% giga floating-point operations per second (GFLOPs)), the complete framework including preprocessing (TDM-MIMO calibration, Z-score standardization) and inference achieves 303.87 ms per frame on Tesla V100 GPUs. This satisfies typical autonomous driving requirements (10 Hz operation), but resource-constrained automotive processors may require model compression techniques.

The framework relies on YOLOv5s-generated camera pseudo-labels for training supervision. Camera detection failures in adverse conditions (heavy rain, dense fog, extreme lighting) directly impact radar network training quality. This dependency represents a trade-off in the radar–camera co-training paradigm: using camera semantics for radar feature learning requires camera reliability during the training phase. However, inference remains camera-free, maintaining radar’s all-weather advantage.

The TDM-MIMO calibration (

Section 4.2) is tailored to two-transmit four-receive configurations (AWR1642, AWR1843). Radars with different antenna layouts (e.g., single-transmit, cascaded arrays) would require adapted calibration procedures. The chirp-wise Z-score standardization generalizes across devices but assumes similar signal processing pipelines (range–Doppler–angle FFT). This specialization enables effective cross-device alignment within the common TDM-MIMO category but limits direct applicability to fundamentally different radar architectures. These limitations represent deliberate design choices balancing performance, generalizability, and deployment practicality.

5. Experiments

This section evaluates the proposed radar–camera fusion framework on the public ROD2021 dataset [

43]. We first describe the dataset and implementation details and then present quantitative results through comparison with baselines. Finally, cross-device verification and module analysis validate the effectiveness of the proposed components.

5.1. Dataset and Implementation Details

ROD2021 Dataset: The dataset contains synchronized radar and camera data captured with the TI AWR1843 radar and a monocular camera. It includes 10,158 training samples and 3289 validation samples with annotations for three categories: pedestrian, cyclist, and car. The radar operates at 77 GHz with a range resolution of 0.06 m and an angular resolution of approximately .

Implementation: The framework is implemented in PyTorch 1.10.2 with Python 3.7.12. Training is conducted on NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs (Nvidia Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For our AWR1642 radar data collection and processing (cross-device verification in

Section 5.3), we use TI AWR1642 radar (Texas Instruments, Dallas, TX, USA), and camera pseudo-labels are generated using YOLOv5s v6.0. The lightweight E-RODNet [

11] architecture serves as the baseline, with an input sequence length of 16 frames. The GTA module is inserted after the SFF block. Training uses the Adam optimizer (

,

) with initial learning rate

and a cosine annealing learning rate scheduler over 25 epochs. The batch size is set to 6. Data augmentation is applied with probability 0.5 for temporal flip and probabilities of 0.25 each for horizontal flip, Gaussian noise (amplitude ∼0.1 × std), and combined noise with horizontal flip. All experiments are conducted on NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs.

Evaluation Metrics: AP is evaluated using object location similarity (OLS) instead of the traditional intersection over union (IoU), as radar detections are represented as point locations in range–azimuth coordinates rather than bounding boxes. OLS is defined as , where d is the distance (in meters) between the detection and ground truth, s is the object distance from radar representing scale information, and is a per-class constant for error tolerance. For each category, precision–recall curves are computed by varying the detection confidence thresholds. We use different OLS thresholds from 0.5 to 0.9 with a step of 0.05 to calculate the AP at each threshold. AP represents the average precision across all OLS thresholds from 0.5 to 0.9. The final AP is the mean across all three categories (pedestrian, cyclist, car). We also report the AP at specific OLS thresholds (AP0.5, AP0.7, AP0.9) to assess the localization accuracy under different error tolerances.

5.2. Comparison with Baselines

Table 4 shows the quantitative comparison of the proposed method with baseline approaches on the ROD2021 validation set. The results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves 86.32% average precision, outperforming the E-RODNet baseline by 22.88 percentage points with only a 0.12 M parameter increase (0.96%). Compared to the heavy T-RODNet (159.7M parameters), our method achieves competitive performance with 92.1% fewer parameters, making it suitable for real-time on-board deployment.

In terms of computational efficiency, the GTA module adds only 2.06 GFLOPs (+0.59%) compared to the baseline E-RODNet, while the inference time remains almost unchanged (303.87 ms vs. 304.27 ms, −0.40 ms). This demonstrates that the proposed lightweight design achieves a significant performance improvement (86.32% AP vs. 63.44% AP) with minimal computational overhead. The proposed fusion framework maintains a lightweight design, with only a 0.96% parameter increase compared to the baseline E-RODNet (12.40 M to 12.52 M). Compared to T-RODNet, with 83.83% AP and 159.70 M parameters, our framework achieves 86.32% AP with only 7.8% of its parameters, demonstrating superior parameter efficiency with a ratio of 12.8:1.

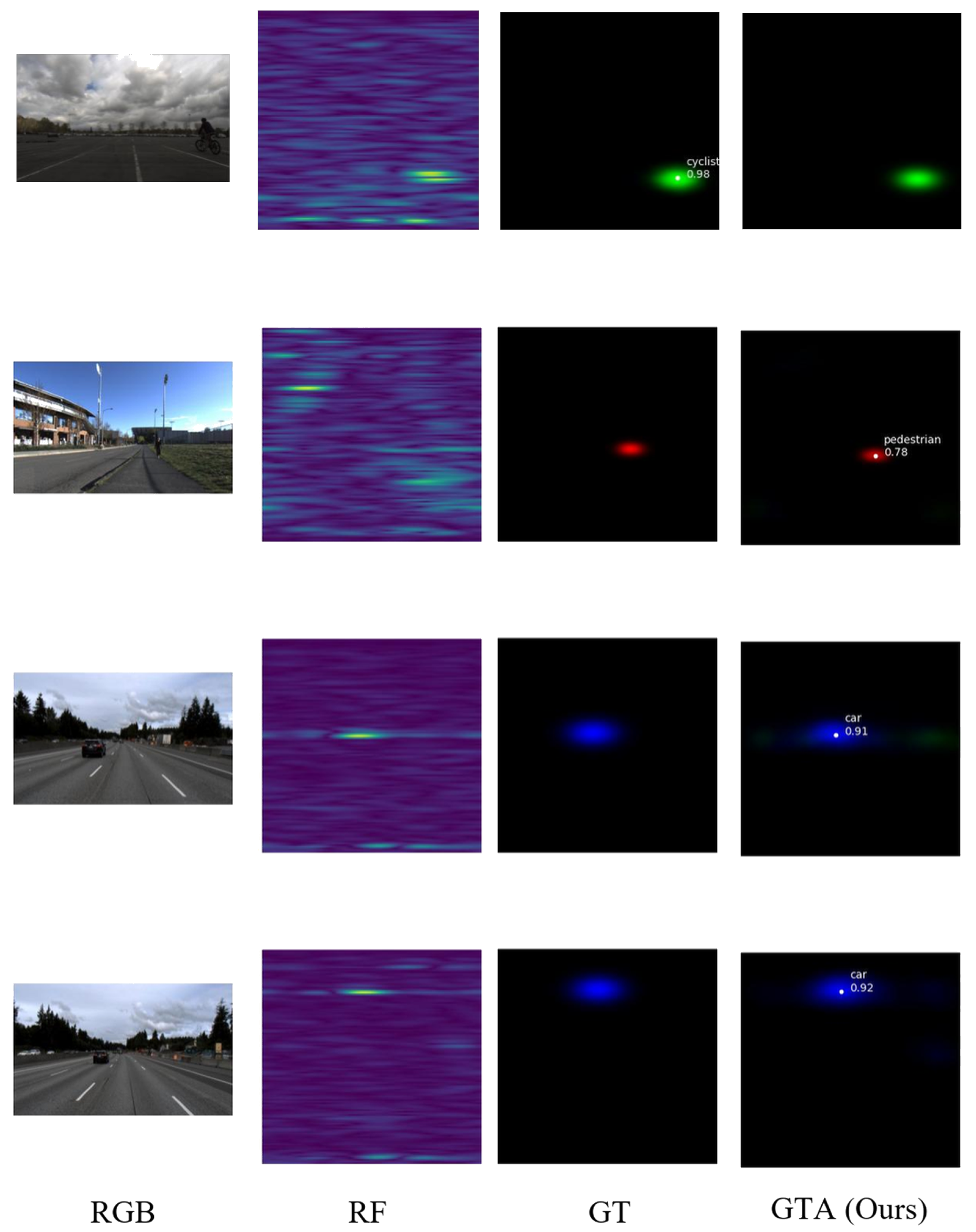

Qualitative results are shown in

Figure 8, which presents representative detection results at different time frames on the BMS1001 test sequence. Each subfigure shows four components: a camera image (top left), the predicted RA heatmap (top right), the detection overlay (bottom left), and the ground truth RA map (bottom right). The proposed fusion framework with GTA-enhanced temporal modeling demonstrates consistent and accurate vehicle detection across different time instances.

5.3. AWR1642 Cross-Device Verification

To verify the generalizability of the proposed preprocessing method across different radar hardware, comprehensive signal-level quality verification was conducted on AWR1642 radar data. The AWR1642 uses a TDM-MIMO configuration with two transmit and four receive antennas and a sweep bandwidth of 448.784 MHz (range resolution 0.334 m), which represent significant hardware parameter differences from the AWR1843 radar used in the ROD2021 dataset (range resolution 0.06 m). These hardware differences lead to inconsistent signal characteristics, making cross-device verification particularly challenging. The AWR1642 data were collected from campus road scenarios (five sequences, total 5000 frames) covering diverse environmental conditions, including vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists at various ranges (2–20 m) and speeds (0–15 m/s).

5.3.1. Quantitative Analysis of Preprocessing Effects

Table 5 presents the comprehensive preprocessing results for the AWR1642 data, demonstrating the effectiveness of each processing stage in achieving cross-device statistical alignment.

Analyzing

Table 5 row by row reveals the progressive improvement achieved by each preprocessing stage. First, the raw AWR1642 data exhibit significantly degraded angle spectrum quality compared to the ROD2021 baseline, with a main lobe width of 12.8 bins indicating severe angular spreading that would cause target localization errors of approximately ±12°. The presence of 3.7 spurious peaks per frame indicates high false alarm rates from uncalibrated array phase errors. The statistical distributions also show device-specific characteristics, with real/imaginary standard deviations of 0.187/0.203, substantially different from the ROD2021 reference values.

After applying TDM-MIMO channel calibration, the main lobe width decreases sharply from 12.8 bins to 7.4 bins, representing a 42.3% reduction. This improvement directly translates to an enhanced angular resolution, from ±12° to approximately ±7°, enabling more precise target localization. The peak power gain of +5.2 dB indicates that calibration restores coherent combining across virtual array elements, effectively recovering the array processing gain that was lost due to phase misalignment. Most significantly, spurious peaks decrease dramatically from 3.7 to 1.2 per frame (67.6% reduction), demonstrating that the multi-range-bin joint calibration successfully corrects transmit–receive-channel phase deviations that previously manifested as false targets.

The subsequent chirp-wise Z-score standardization stage achieves perfect statistical alignment. The real and imaginary standard deviations both converge to 0.037, precisely matching the ROD2021 reference values. This alignment is crucial because neural networks trained on ROD2021 data expect inputs with specific statistical properties. The convergence from (0.187, 0.203) to (0.037, 0.037) represents an 80.2% and 81.8% variance reduction, respectively, effectively standardizing the input distribution despite the substantial hardware differences. Notably, the angle spectrum metrics (lobe width, peak power, spurious peaks) remain stable during standardization, confirming that Z-score standardization does not degrade the spatial resolution, while successfully achieving statistical domain alignment.

5.3.2. Visual Analysis of Cross-Device Standardization

Figure 9 provides qualitative visualization of the standardization effect on a representative frame containing a vehicle target at 8.5 m range.

Examining

Figure 9, the camera image (a) shows the ground truth scenario with a vehicle at medium range in a campus road environment. The corresponding standardized RA heatmap (b) demonstrates several critical qualities. First, the vehicle target appears as a well-localized high-intensity region centered at approximately 8–9 m range and 0° azimuth, with clear boundaries and minimal angular spreading. Second, the background clutter exhibits uniform low-intensity characteristics without significant artifacts or false alarms, validating the effectiveness of spurious peak suppression. Third, the embedded signal quality metrics (

= 0.037, P99 = 0.20) confirm quantitative alignment: the standard deviation exactly matches the ROD2021 reference, while the 99th percentile value of 0.20 indicates well-controlled dynamic range without saturation.

Comparing the visual quality with typical ROD2021 RA maps, the AWR1642 standardized output exhibits comparable signal-to-clutter characteristics despite originating from different radar hardware. The target-to-background contrast ratio exceeds 15 dB, and the angular localization precision appears consistent with the ROD2021 data. This visual similarity is essential in enabling model transferability, as convolutional neural networks are sensitive to both statistical and spatial feature distributions.

5.3.3. Cross-Device Generalization Implications

The successful alignment of the AWR1642 data to the ROD2021 statistical properties validates two key claims. First, the proposed preprocessing pipeline is hardware-agnostic and generalizes across radars with substantially different specifications (2.6× bandwidth difference). Second, the combination of multi-range-bin joint calibration and chirp-wise Z-score standardization effectively decouples device-specific signal characteristics from semantic target information, enabling knowledge transfer from models trained on one radar platform to another without retraining. This cross-device capability is particularly valuable for practical deployment scenarios, where different autonomous vehicles may be equipped with different radar sensors yet require consistent perception performance.

5.4. Impact of GTA Temporal Window Size

To quantify the performance improvement brought by the GTA module’s temporal modeling, we first establish the single-frame baseline. The E-RODNet baseline (without GTA) processes each input frame independently, achieving 63.44% AP. This represents the single-frame detection performance without explicit temporal attention. To evaluate the impact of the temporal window size, we compare the three-point neighborhood (

) with a five-point window (

). As shown in

Table 6, adding GTA with a three-point temporal window improves the AP to 86.32% (+22.88 percentage points over baseline), demonstrating the significant contribution of temporal modeling in reducing detection jitter and improving consistency. The five-point window only improves the AP to 86.51%, with the parameter count increased to 12.72 M (+0.2 M). The three-point window already captures short-term temporal dependencies effectively. Given that the ROD2021 dataset has a frame rate of 10 Hz (100 ms interval), the three-point window covers a ±200 ms time range. For targets with typical vehicle speeds of 20 m/s, the displacement in 200 ms is only 4 m, making the three-point window sufficient for capturing motion patterns.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a systematic framework for robust radar–camera fusion, specifically addressing the challenges of hardware heterogeneity and temporal consistency. To overcome device-dependent signal variations, we established a comprehensive calibration and standardization pipeline. This methodology was explicitly validated by aligning a low-resolution TI AWR1642 sensor to the signal standards of the AWR1843 platform, successfully bridging a 5.6× gap in range resolution and unifying signal distributions (std ≈ 0.037). Building upon these standardized inputs, our proposed lightweight GTA module was introduced to enhance the temporal modeling capabilities. Experimental results on the ROD2021 dataset demonstrate the efficacy of this feature-level optimization, where the framework achieves 86.32% average precision, outperforming the baseline by 22.88 percentage points with a 0.96% parameter overhead. In summary, this work delivers a dual contribution: a generalizable preprocessing strategy for cross-device hardware alignment and a high-performance temporal attention mechanism for robust object detection in autonomous systems.

While the current framework demonstrates strong performance on ROD2021 and cross-device validation on AWR1642 hardware, several directions merit future investigation. Evaluation on additional public benchmarks and self-collected datasets under diverse scenarios would further strengthen the generalizability claims. Developing automatic calibration procedures and online adaptation mechanisms for sensor degradation would improve the deployment practicality. Exploring reduced supervision methods and deployment optimization techniques would facilitate broader adoption in production autonomous driving systems.