A Longitudinal Analysis of a Motor Skill Parameter in Junior Triathletes from a Wearable Sensor

Abstract

1. Introduction

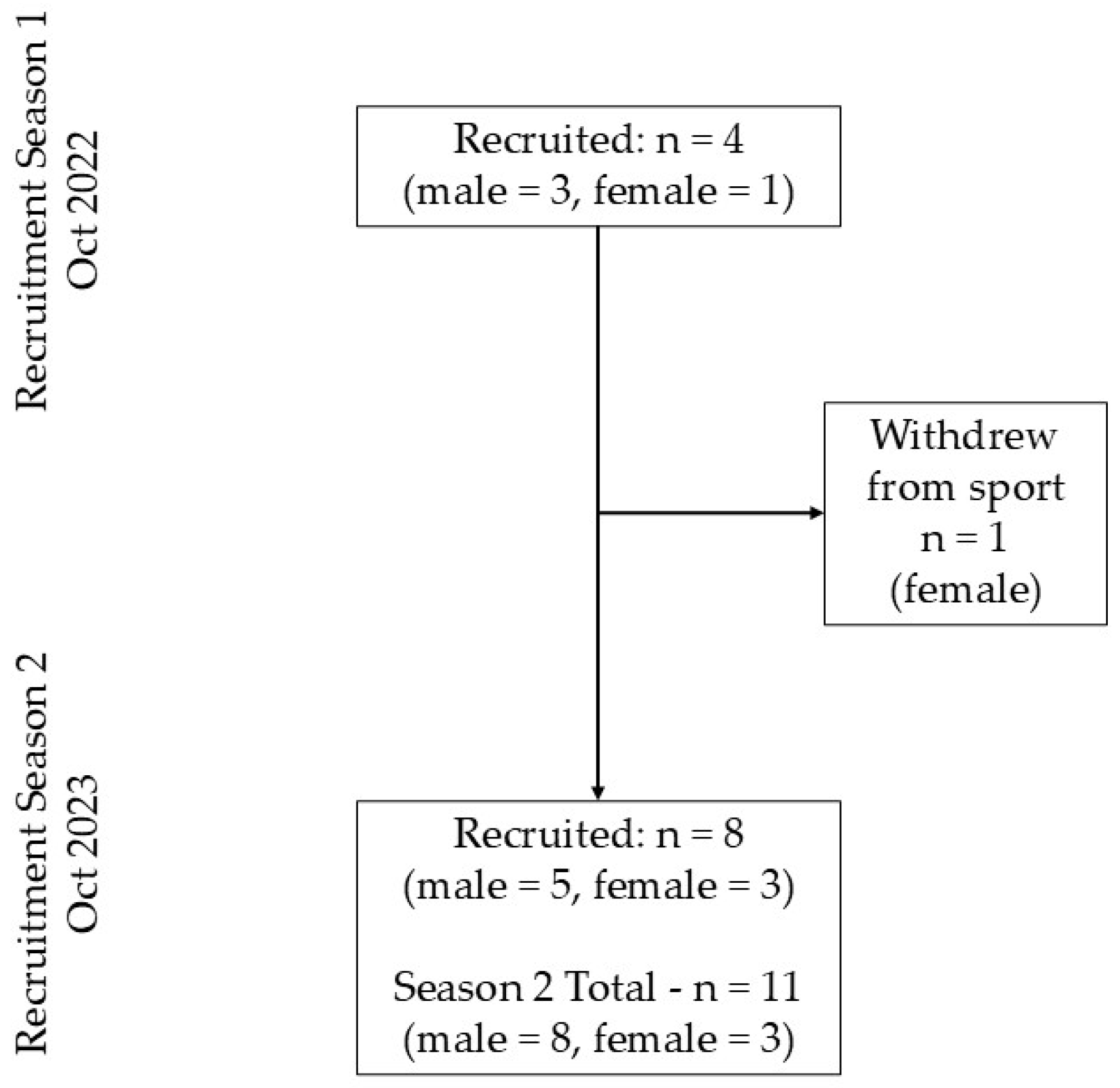

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- C is the average cadence;

- is the population-level intercept;

- is the fixed (linear) effect of the week number;

- W is the week number;

- is the fixed effect of the season (with the appropriate coding for categorical levels);

- is the random intercept for athlete ;

- is the random slope of the week number for athlete ;

- is the residual error;

- is an unknown smooth function for the week number (the penalised smooth estimated by s(W)).

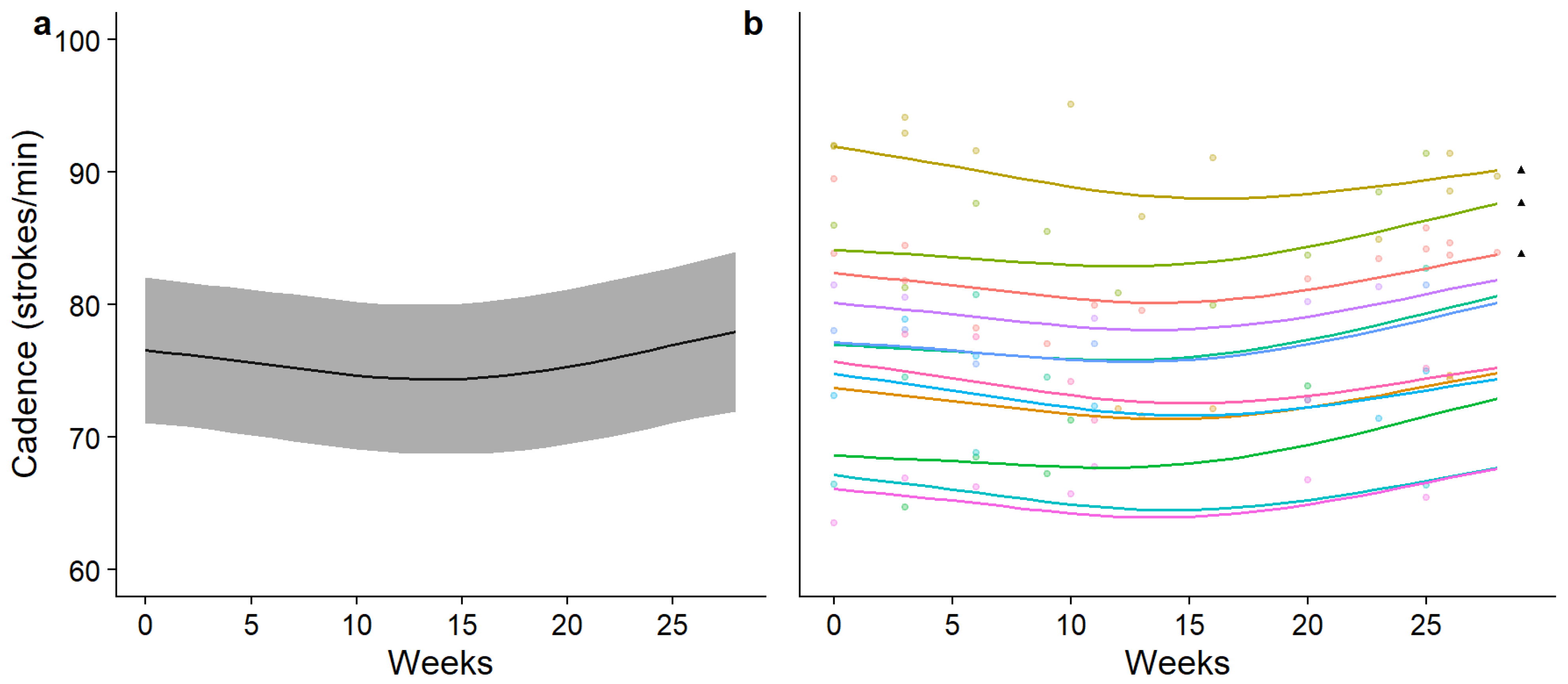

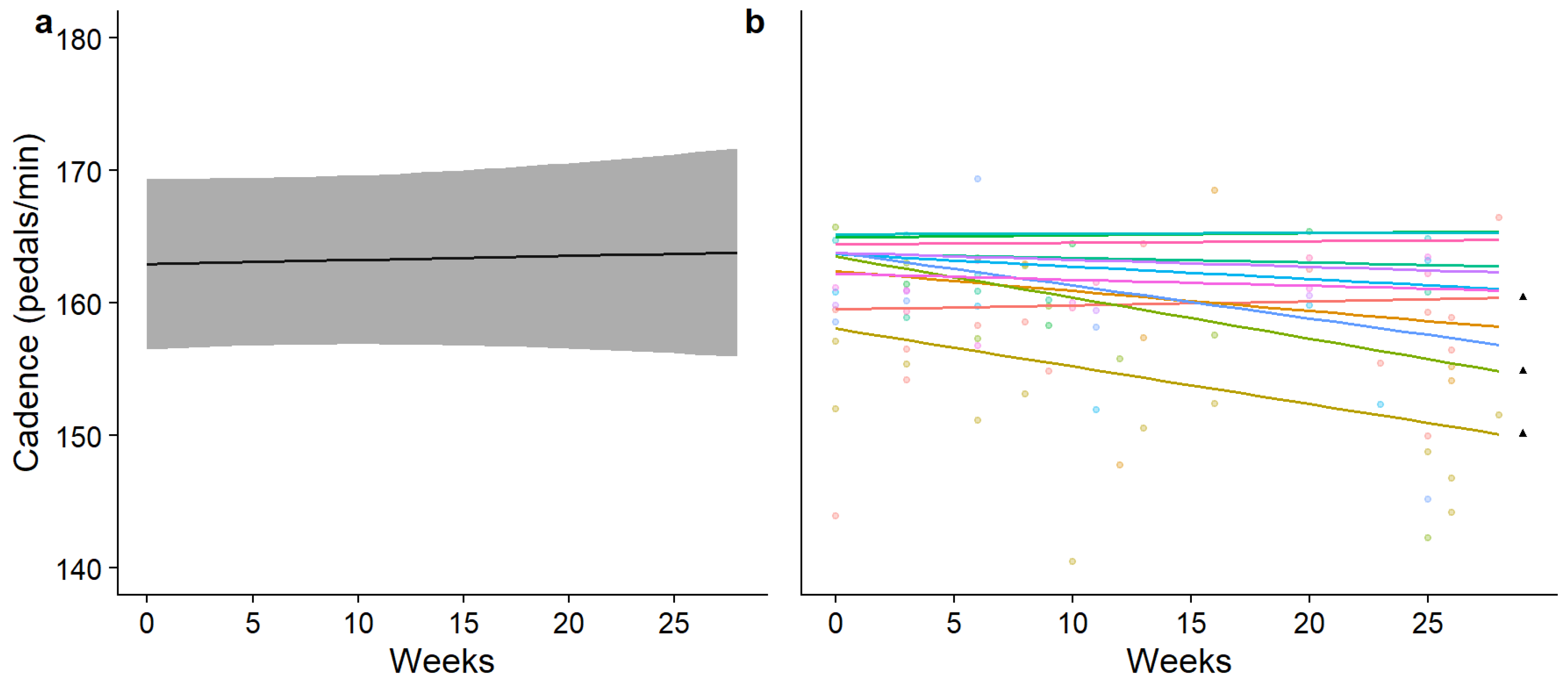

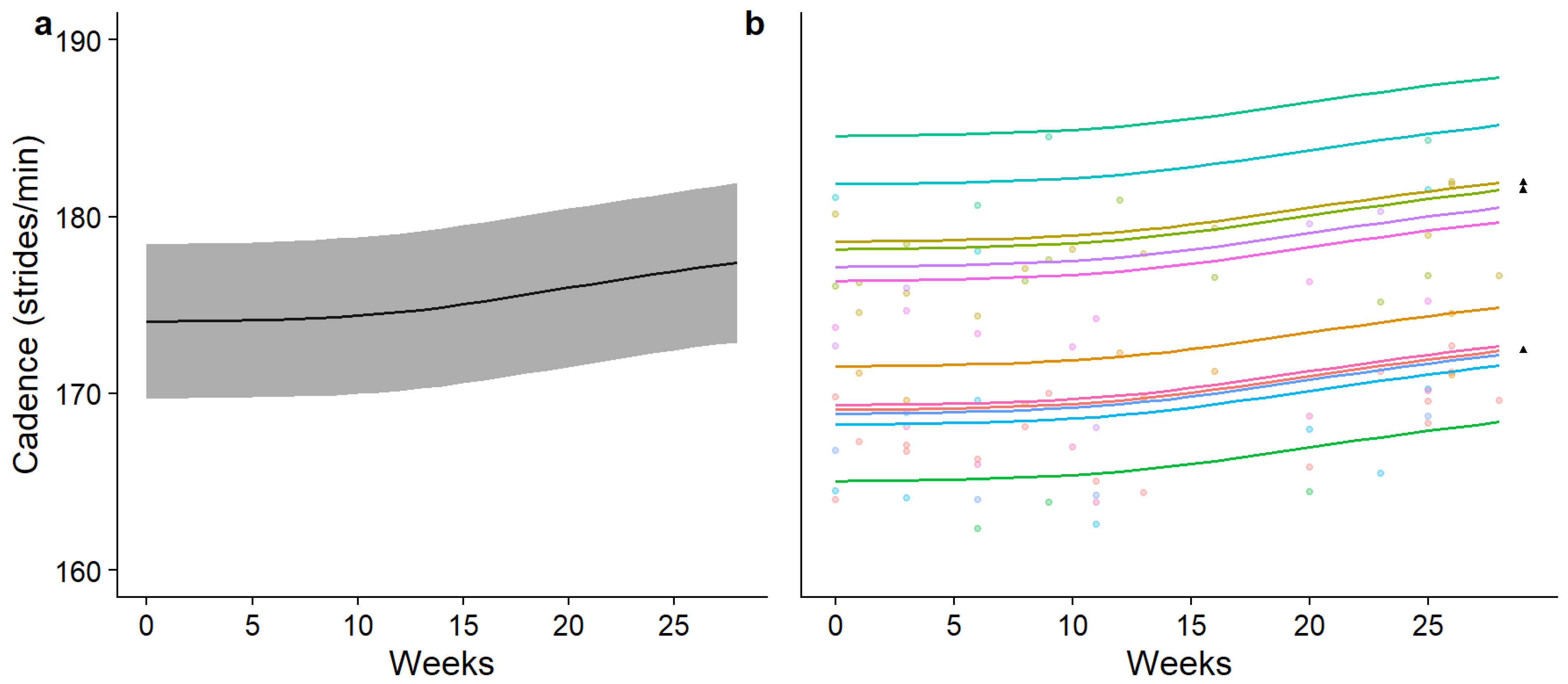

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| GMP | Generalised Motor Program |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GAM | Generalised Additive Model |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| REML | Restricted Maximum Likelihood |

References

- Farrow, D.; Robertson, S. Development of a Skill Acquisition Periodisation Framework for High-Performance Sport. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris-Binelli, K.; Müller, S.; van Rens, F.E.C.A.; Harbaugh, A.G.; Rosalie, S.M. Individual Differences in Performance and Learning of Visual Anticipation in Expert Field Hockey Goalkeepers. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 52, 101829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesher, S.M.; Rosalie, S.M.; Netto, K.J.; Charlton, P.C.; van Rens, F.E.C.A. A Qualitative Exploration of the Motor Skills Required for Elite Triathlon Performance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 62, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesida, Y.; Papi, E.; McGregor, A.H. Exploring the Role of Wearable Technology in Sport Kinematics and Kinetics: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, L.C.; Clermont, C.A.; Bošnjak, E.; Ferber, R. The Use of Wearable Devices for Walking and Running Gait Analysis Outside of the Lab: A Systematic Review. Gait Posture 2018, 63, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camomilla, V.; Bergamini, E.; Fantozzi, S.; Vannozzi, G. Trends Supporting the in-Field Use of Wearable Inertial Sensors for Sport Performance Evaluation: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Mittal, V. Wearable Sensors for Real-Time Kinematics Analysis in Sports: A Review. IEEE Sens. 2021, 21, 1187–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranzinger, S.; Kranzinger, C.; Kremser, W.; Duemler, B. Performance Tracking in Female Youth Soccer through Wearables and Subjective Assessments. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1627820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, B.L.; van der Ploeg, G.E.; Bourdon, P.C.; Butler, S.R.; Crowther, R.G. Evaluation of Athlete Monitoring Tools across 10 Weeks of Elite Youth Basketball Training: An Explorative Study. Sports 2023, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, A.C.; Chaves, R.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G.; Vasconcelos, O.; Barnett, L.M.; Tani, G.; Hedeker, D.; Maia, J. Modelling the Dynamics of Children’s Gross Motor Coordination. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 2243–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.P.; Stodden, D.F.; Lopes, V.P. Developmental Pathways of Change in Fitness and Motor Competence Are Related to Overweight and Obesity Status at the End of Primary School. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solum, M.; Lorås, H.; Pedersen, A.V. A Golden Age for Motor Skill Learning? Learning of an Unfamiliar Motor Task in 10-Year-Olds, Young Adults, and Adults, When Starting from Similar Baselines. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.I.; Lohse, K.R.; Lopes, T.C.V.; Williams, A.M. Individual Differences in Motor Skill Learning: Past, Present and Future. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2021, 78, 102818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschini, G.; Terzini, M.; Zanetti, E.M. Learning Curves of Elite Car Racers. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2017, 12, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, M.J.; Bates, D.M. Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models for Repeated Measures Data. Biometrics 1990, 46, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.A. A Schema Theory of Discrete Motor Learning. Psychol. Rev. 1975, 82, 225–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westendorp, M.; Hartman, E.; Houwen, S.; Huijgen, B.C.H.; Smith, J.; Visscher, C. A Longitudinal Study on Gross Motor Development in Children with Learning Disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Guan, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Hu, Z. Towards Energy-Autonomous Wearables: Multimodal Harvesting Technologies and Sustainable Applications. Innov. Mater. 2025, 3, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesher, S.M.; Rosalie, S.M.; Chapman, D.W.; Charlton, P.C.; van Rens, F.E.C.A.; Netto, K.J. A Single Trunk-Mounted Wearable Sensor to Measure Motor Performance in Triathletes During Competition. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part P J. Sports Eng. Technol. 2024, 238, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesher, S.M.; Martinotti, C.; Chapman, D.W.; Rosalie, S.M.; Charlton, P.C.; Netto, K.J. Automatic Recognition of Motor Skills in Triathlon: Creating a Performance Analysis Tool. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Silva, C.; Santos, M.; Fernandes, T.; Faria, S. Framework for Intelligent Swimming Analytics with Wearable Sensors for Stroke Classification. Sensors 2021, 21, 5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollaus, B.; Volmer, J.C.; Fleischmann, T. Cadence Detection in Road Cycling Using Saddle Tube Motion and Machine Learning. Sensors 2022, 22, 6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Calbre: A Participant Classification Framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beanland, E.; Main, L.C.; Aisbett, B.; Gastin, P.; Netto, K. Validation of GPS and Accelerometer Technology in Swimming. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2014, 17, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wundersitz, D.W.T.; Gastin, P.; Richter, C.; Robertson, S.J.; Netto, K.J. Validity of a Trunk-Mounted Accelerometer to Assess Peak Accelerations During Walking, Jogging and Running. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2014, 15, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.R.; Vicenzino, B.; Blanch, P.; Dowlan, S.; Hodges, P.W. Does Cycling Effect Motor Coordination of the Leg During Running in Elite Triathletes? J. Sci. Med. Sport 2008, 11, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeling, P.D.; Bishop, D.J.; Landers, G.J. Effect of Swimming Intensity on Subsequent Cycling and Overall Triathlon Performance. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.N.; Smith, G.M. Additive and Generalised Additive Modelling. In Analysing Ecological Data; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, J.E.; Neath, A.A. The Akaike Information Criterion: Background, Derivation, Properties, Application, Interpretation, and Refinements. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2019, 11, e1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neath, A.A.; Cavanaugh, J.E. The Bayesian Information Criteion: Background, Derivation, and Applications. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2012, 4, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.M.; Verswijveren, S.J.J.M.; Colvin, B.; Lubans, D.R.; Telford, R.M.; Lander, N.J.; Schott, N.; Tietjens, M.; Hesketh, K.D.; Morgan, P.J.; et al. Motor Skill Competence and Moderate- and Vigorous Intensity Physical Activity: A Linear and Non-Linear Cross-Sectional Analysis of Eight Pooled Trials. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.E.; Hopkins, W.G.; Roberts, A.D.; Pyne, D.B. Monitoring Seasonal and Long-Term Changes in Test Performance in Elite Swimmers. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2006, 6, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzaroba, P.V.; Machado, F.A. Effect of Age, Anthropometry, and Distance in Stroke Parameters of Young Swimmers. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2014, 9, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormehl, S.; Osborough, C. Effect of Age, Sex, and Race Distance on Front Crawl Stroke Parametrs in Subelte Adolescent Swimmers During Competition. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2015, 27, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, I.S. Is There an Economical Running Tehnique? A Review of Modifiable Biomechanical Factors Affecting Running Economy. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.; Figueiredo, P.; Morais, S.; Alves, F.; Toussaint, H.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Fernandes, R.J. Biomechanics, Energetics and Coordination During Extreme Swimming Intensity: Effect of Performance Level. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 16, 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brandt, F.A.P.; Khudair, M.; Hettinga, F.J.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T. Be Aware of the Benefits of Drafting in Sports and Take Your Advantage: A Meta-Analysis. Transl. Sports Med. 2023, 2023, 3254847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafer, J.F.; Brown, A.M.; deMille, P.; Hillstrom, H.J.; Garber, C.E. The Effect of a Cadence Retraining Protocol on Running Biomechanics and Efficiency: A Pilot Study. J. Sport Sci. 2015, 33, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, I.; Federolf, P. Focus of Attention in Coach Instructions for Technique Training in Sports: A Scrutinized Review of Review Studies. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Krampe, R.T.; Tesch-Römer, C. The Role of Deliberate Practise in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. Psychol. Rev. 1993, 100, 363–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmoni, A.W.; Schmidt, R.A.; Walter, C.B. Knowledge of Results and Motor Learning: A Review and Critical Reappraisal. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 355–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, R.; Anderson, D. Motor Learning and Control: Concepts and Applications; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, H.F. The Formation of Learning Sets. Psychol. Rev. 1949, 56, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Discipline | Model Type | AIC | BIC | r2 | D | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swimming | Linear | 426.39 | 474.85 | 0.88 | - | - |

| Non-Linear | 413.61 | 470.15 | 0.90 | 106.71 | <0.01 | |

| Cycling | Linear | 537.46 | 578.11 | 0.31 | - | - |

| Non-Linear | 537.51 | 578.22 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| Running | Linear | 392.22 | 428.59 | 0.86 | - | - |

| Non-Linear | 391.14 | 431.50 | 0.87 | 16.71 | 0.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chesher, S.M.; Chapman, D.W.; Liew, B.; Rosalie, S.M.; Riddell, H.; Charlton, P.C.; Netto, K.J. A Longitudinal Analysis of a Motor Skill Parameter in Junior Triathletes from a Wearable Sensor. Sensors 2026, 26, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010096

Chesher SM, Chapman DW, Liew B, Rosalie SM, Riddell H, Charlton PC, Netto KJ. A Longitudinal Analysis of a Motor Skill Parameter in Junior Triathletes from a Wearable Sensor. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleChesher, Stuart M., Dale W. Chapman, Bernard Liew, Simon M. Rosalie, Hugh Riddell, Paula C. Charlton, and Kevin J. Netto. 2026. "A Longitudinal Analysis of a Motor Skill Parameter in Junior Triathletes from a Wearable Sensor" Sensors 26, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010096

APA StyleChesher, S. M., Chapman, D. W., Liew, B., Rosalie, S. M., Riddell, H., Charlton, P. C., & Netto, K. J. (2026). A Longitudinal Analysis of a Motor Skill Parameter in Junior Triathletes from a Wearable Sensor. Sensors, 26(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010096