Multi-Scale Interactive Network with Color Attention for Low-Light Image Enhancement

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We propose an efficient and robust LLIE method named MSINet, which integrates CNN and Transformer structures for balancing local detail extraction and global feature encoding. Extensive experiments show our MSINet can generate visually pleasing images.

- (2)

- We proposed a cross-scale Transformer module combining cross-scale attention (CSA) and multi-head self-attention (MHSA) to enhance the model’s multi-scale feature learning. Meanwhile, the CNN-based branch can fully explore the local feature.

- (3)

- We proposed a self-attention-based color correction branch to dig up color distribution weighting for color correction in the LLIE tasks. Additionally, we design a fusion block to analyze the correlation and complementarity of global–local features.

2. Related Works

2.1. CNN-Based LLIE Enhancement

2.2. Transformer-Based LLIE Methods

2.3. Diffusion-Based LLIE Methods

3. Methodology

3.1. CNN-Based Branch

3.2. Transformer-Based Branch

3.3. Color Correction Branch

3.4. Loss Function

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Implementation Details

4.2. Experimental Settings

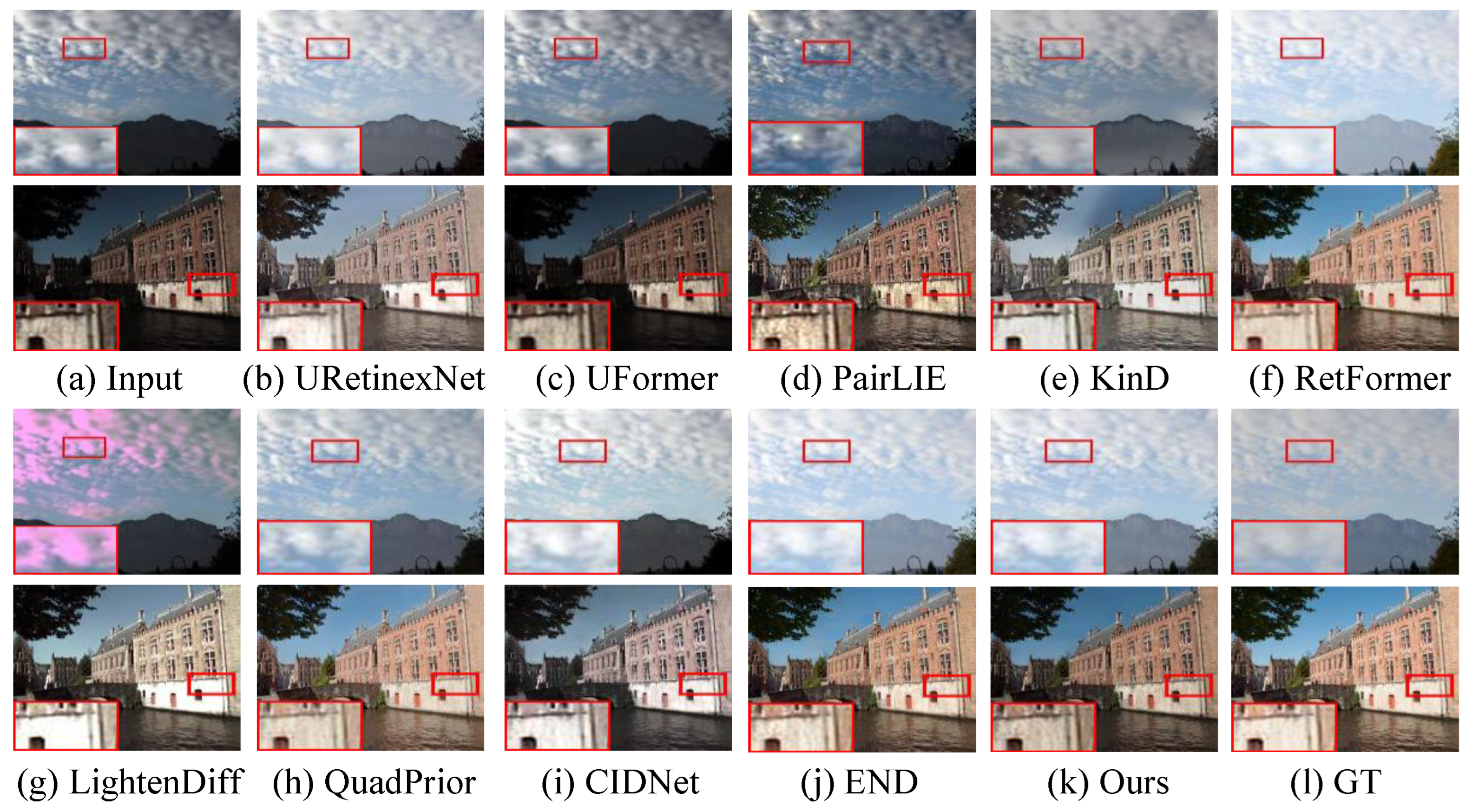

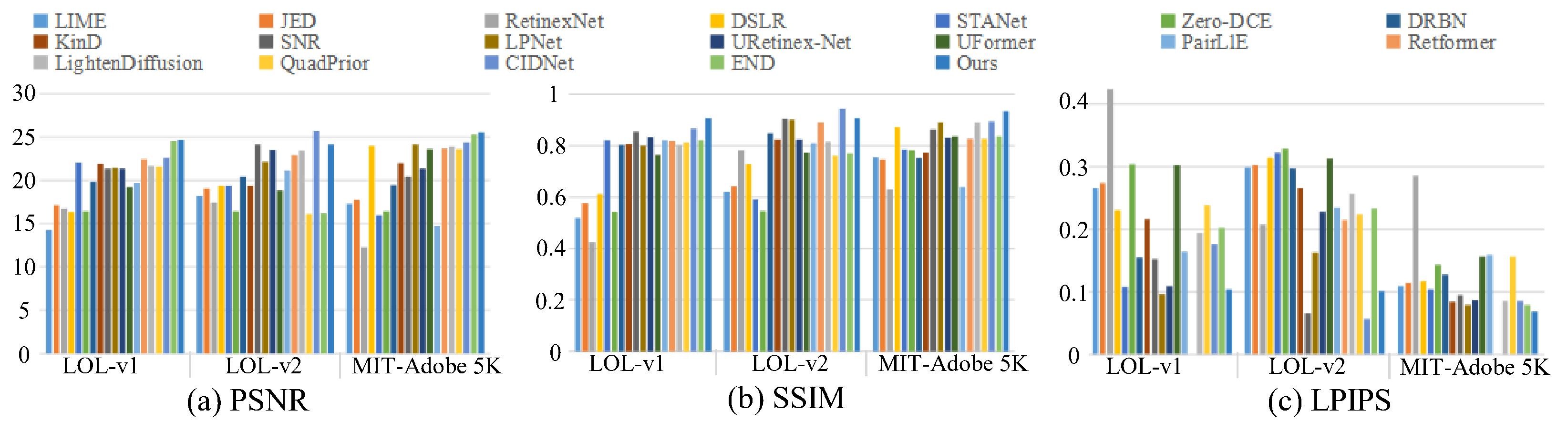

4.3. Comprehensive Evaluation on Paired Datasets

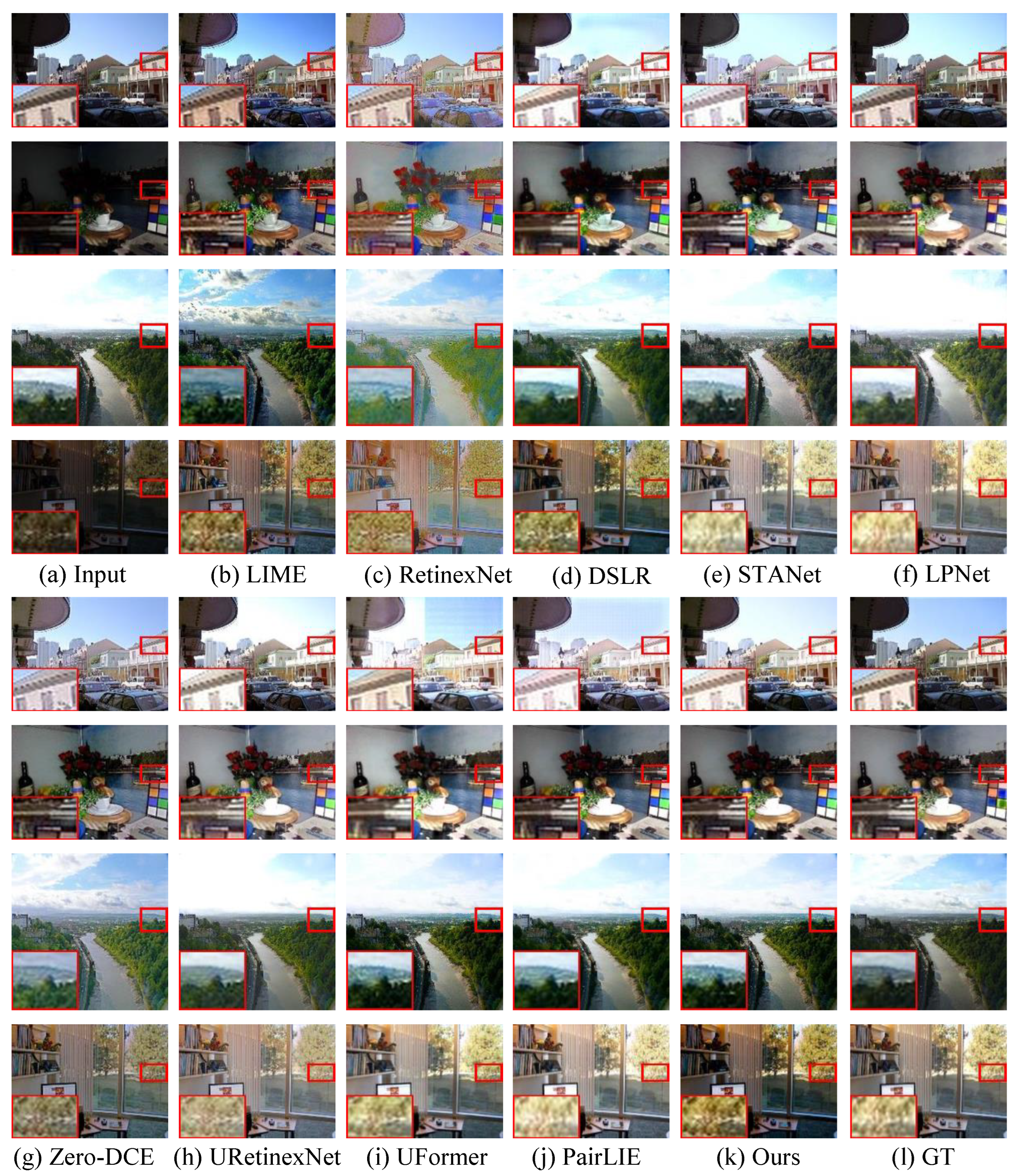

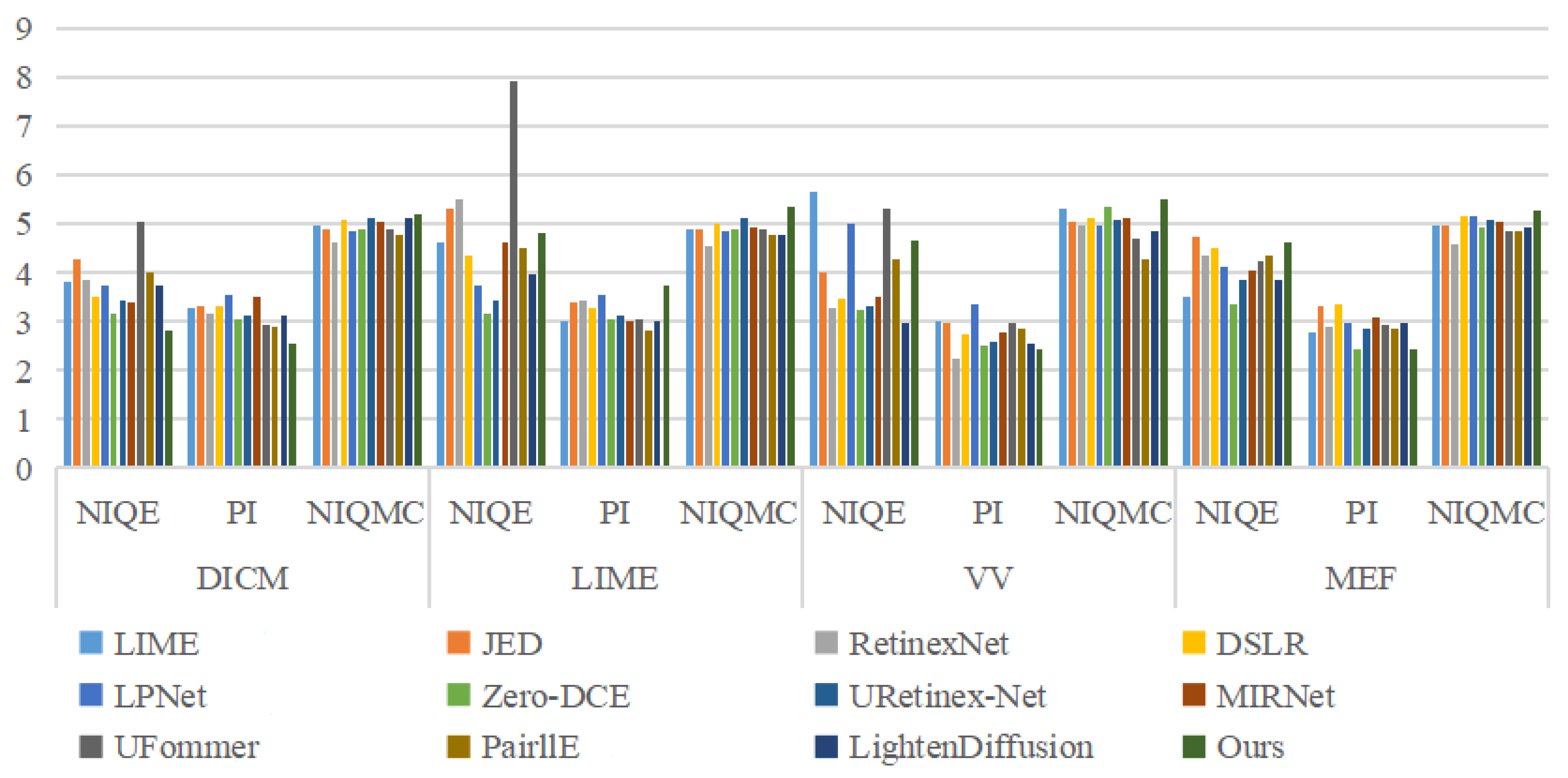

4.4. Comprehensive Evaluation on Unpaired Datasets

4.5. Comprehensive Evaluation of Detail Enhancement

4.6. Comprehensive Evaluation of Color Correction

4.7. Comprehensive Evaluation of Computational Complexity

4.8. Ablation Study

4.9. Generalization of Our Proposed Method

4.10. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nasir, M.F.; Rehman, M.U.; Hussain, I. A self-attention guided approach for advanced underwater image super-resolution with depth awareness. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 1715–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jia, T.; Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Lu, H.; Lin, S.; Cai, D.; Chen, D. AO-DETR: Anti-overlapping DETR for X-Ray prohibited items detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 12076–12090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Guo, C.; Loy, C.C. Learning to enhance low-light image via zero-reference deep curve estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 4225–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, M.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Pan, S.; Zhou, C. Flow2GNN: Flexible two-way flow message passing for enhancing GNNs beyond homophily. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 6607–6618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, W.; Bi, L. Mine image enhancement using adaptive bilateral gamma adjustment and double plateaus histogram equalization. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 12643–12660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, W.; Huang, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, J. Sparse gradient regularized deep retinex network for robust low-light image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 2072–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Q. Guided filter-inspired network for low-light RAW image enhancement. Sensors 2025, 25, 2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, C.; Yan, W.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, M. Low-light image joint enhancement optimization algorithm based on frame accumulation and multi-scale Retinex. Ad Hoc Netw. 2021, 113, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Xia, J.; Yang, Z.; Pan, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y. Meta-learning based domain prior with application to optical-ISAR image translation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 7041–7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lore, K.G.; Akintayo, A.; Sarkar, S. LLNet: A deep autoencoder approach to natural low-light image enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2017, 61, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, M.; Cheng, W.H.; Liu, J. Joint enhancement and denoising method via sequential decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Florence, Italy, 27–30 May 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Chen, Q.; Do, M.N.; Koltun, V. Seeing motion in the dark. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3185–3194. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, T.; Xu, C.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ma, S.; Xu, C.; Xu, C.; Gao, W. Pre-trained image processing transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 12299–12310. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lu, H.; Wang, W.; Lan, R. Brighten up images via dual-branch structure-texture awareness feature interaction. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2023, 31, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Fang, F.; Li, F.; Zhang, G. Luminance-aware pyramid network for low-light image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2020, 23, 3153–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Weng, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Yang, W.; Jiang, J. Uretinex-net: Retinex-based deep unfolding network for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 5901–5910. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Hao, Z.; Wang, Y. Physics-guided deep neural networks for bathymetric mapping using Sentinel-2 multi-spectral imagery. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1636124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Wang, W.; Yang, W.; Liu, J. Deep retinex decomposition for low-light enhancement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.04560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Kim, W. DSLR: Deep stacked Laplacian restorer for low-light image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2020, 23, 4272–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Hong, R.; Xu, M.; Yan, S.; Wang, M. Deep color consistent network for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 1899–1908. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yin, B.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Liu, H. A Low Light Image Enhancement Method Based on Dehazing Physical Model. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. (CMES) 2025, 143, 1595–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Yi, X.; Ma, J. CRetinex: A progressive color-shift aware retinex model for low-light image enhancement. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 132, 3610–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ai, H.; Zhou, P.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Chen, W. Low-light image dehazing and enhancement via multi-feature domain fusion. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, B.; Zhou, T.; Liu, B.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Plaza, A. Multi-scale autoencoder suppression strategy for hyperspectral image anomaly detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 5115–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, K.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, J.; Zhai, G.; Zhang, W. Perceptual information fidelity for quality estimation of industrial images. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Gao, C.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, X. Correlation information enhanced graph anomaly detection via hypergraph transformation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 55, 2865–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Gong, X.; Liu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, C.; Shen, X.; Yang, J.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Z. EnlightenGAN: Deep light enhancement without paired supervision. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 2340–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, C.; Guo, J.; Loy, C.C.; Hou, J.; Kwong, S.; Cong, R. Zero-reference deep curve estimation for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 1780–1789. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Su, J.N.; Fan, G.; Gan, M.; Chen, C.P. GACA: A gradient-aware and contrastive-adaptive learning framework for low-light image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Pang, G.; Shi, K.; Wu, P.; Dong, W.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. HVI: A new color space for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 5678–5687. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Cun, X.; Bao, J.; Zhou, W.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Uformer: A general u-shaped transformer for image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 17683–17693. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. S2DBFT: Spectral–Spatial Dual-Branch Fusion Transformer for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Bian, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Timofte, R.; Zhang, Y. Retinexformer: One-stage retinex-based transformer for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 4–6 October 2023; pp. 12504–12513. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Meng, N.; Lam, E.Y. LRT: An efficient low-light restoration transformer for dark light field images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 4314–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zuo, Z.; Su, S.; Zhao, B. Infrared target detection based on image enhancement and an improved feature extraction network. Drones 2025, 9, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Zhong, Y.; Qin, X. PPformer: Using pixel-wise and patch-wise cross-attention for low-light image enhancement. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2024, 241, 103930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Huang, Y.; Su, W.; Zhu, F.; Liu, Q. FFTFormer: A spatial-frequency noise aware CNN-Transformer for low light image enhancement. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 314, 113055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brateanu, A.; Balmez, R.; Avram, A.; Orhei, C.; Ancuti, C. LYT-NET: Lightweight YUV Transformer-Based Network for Low-Light Image Enhancement. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2025, 32, 2065–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Xu, P.; Li, Z.; ATO, W.X. An illumination-guided dual attention vision transformer for low-light image enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 158, 111033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Min, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J. Towards Scale-Aware Low-Light Enhancement via Structure-Guided Transformer Design. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 1460–1470. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, A.; Liu, X.; Han, S.; Liu, S. Lightendiffusion: Unsupervised low-light image enhancement with latent-retinex diffusion models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.08939. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Wang, X.; Huang, D.; He, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Xia, Q. KEDM: Knowledge-embedded diffusion model for infrared image festriping. IEEE Photonics J. 2025, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, F.; Bronik, K.; Papiez, B.W. DiffuSeg: Domain-driven diffusion for medical image segmentation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 3619–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, L.; Ma, J. Diff-retinex: Rethinking low-light image enhancement with a generative diffusion model. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 4–6 October 2023; pp. 12302–12311. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, L.; Ma, J. Diff-Retinex++: Retinex-driven reinforced diffusion model for low-light image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 6823–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Ye, T.; Chen, S.; Fu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chai, W.; Xing, Z.; Li, W.; Zhu, L.; Ding, X. Aglldiff: Guiding diffusion models towards unsupervised training-free real-world low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 5307–5315. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Difflle: Diffusion-based domain calibration for weak supervised low-light image enhancement. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2025, 133, 2527–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liao, X.; Liang, J.; Shi, B.; Xu, Y.; Le Callet, P. Detail-preserving diffusion models for low-light image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 3396–3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Luo, T.; Jiang, G.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, L.; He, Z. DiffDark: Multi-prior integration driven diffusion model for low-light image enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 168, 111814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, A.; Fan, H.; Han, S.; Liu, S. Low-light image enhancement with wavelet-based diffusion models. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2023, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Wang, J.; Zuo, F.; Su, H.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y. DCGSD: Low-light image enhancement with dual-conditional guidance sparse diffusion model. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 7792–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, C.W.; Shen, X.; Zheng, W.S.; Jia, J. Underexposed photo enhancement using deep illumination estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 6849–6857. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wan, R.; Yang, W.; Li, H.; Chau, L.P.; Kot, A. Low-light image enhancement with normalizing flow. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Pomona, CA, USA, 24–28 October 2022; Volume 36, pp. 2604–2612. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X. LIME: A method for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 15–19 October 2016; pp. 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Chen, H.; Xu, C.; Jin, Y.; Zhu, C. Structure-texture aware network for low-light image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 4983–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H.; Shao, L. Learning enriched features for real image restoration and enhancement. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part XXV 16. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 492–511. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. From fidelity to perceptual quality: A semi-supervised approach for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 3063–3072. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X. Kindling the darkness: A practical low-light image enhancer. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Nice, France, 21–25 October 2019; pp. 1632–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Fu, J.; Liu, J. Zero-reference low-light enhancement via physical quadruple priors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024; pp. 26057–26066. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Yan, X.; Hou, X.; Zhang, K.; Dun, Y. Extracting noise and darkness: Low-light image enhancement via dual prior guidance. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 1700–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.; Fan, X.; Luo, Z. Retinex-inspired unrolling with cooperative prior architecture search for low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 10561–10570. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C.W.; Jia, J. Snr-aware low-light image enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 17714–17724. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.; Lee, C. Feature extraction based on the Bhattacharyya distance. Pattern Recognit. 2003, 36, 1703–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheremkhin, P.; Lesnichii, V.; Petrov, N. Use of spectral characteristics of DSLR cameras with Bayer filter sensors. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2014; Volume 536, p. 012021. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Ying, Z.; Li, T.H.; Li, G. LECARM: Low-light image enhancement using the camera response model. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 29, 968–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Token Sizes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19.88 | 20.16 | 20.73 | 20.89 | 21.03 |

| 2 | 20.16 | 22.12 | 22.75 | 22.83 | 22.96 |

| 3 | 20.73 | 22.75 | 23.03 | 24.72 | 24.62 |

| 4 | 20.89 | 22.83 | 24.72 | 24.61 | 24.32 |

| 5 | 21.03 | 22.96 | 24.62 | 24.32 | 24.27 |

| 6 | 22.26 | 23.41 | 24.10 | 24.28 | 24.19 |

| Methods | LOL-v1 | LOL-v2 | MIT-Adobe 5K | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR | SSIM | LPIPS | PSNR | SSIM | LPIPS | PSNR | SSIM | LPIPS | |

| LIME [54] | 14.26 | 0.5187 | 0.2659 | 18.24 | 0.6224 | 0.2987 | 17.31 | 0.7567 | 0.1089 |

| JED [11] | 17.15 | 0.5773 | 0.2741 | 19.05 | 0.6431 | 0.3025 | 17.72 | 0.7476 | 0.1139 |

| RetinexNet [18] | 16.76 | 0.4239 | 0.4239 | 17.41 | 0.7811 | 0.2074 | 12.30 | 0.6298 | 0.2861 |

| DSLR [19] | 16.35 | 0.6129 | 0.2307 | 19.37 | 0.7273 | 0.3146 | 24.01 | 0.8734 | 0.1164 |

| STANet [55] | 22.03 | 0.8213 | 0.1073 | 19.36 | 0.5911 | 0.3227 | 15.98 | 0.7854 | 0.1039 |

| Zero-DCE [28] | 16.43 | 0.5421 | 0.3034 | 16.43 | 0.5474 | 0.3291 | 16.39 | 0.7839 | 0.1435 |

| DRBN [57] | 19.86 | 0.8046 | 0.1547 | 20.38 | 0.8491 | 0.2977 | 19.45 | 0.7521 | 0.1275 |

| KinD [58] | 21.87 | 0.8077 | 0.2157 | 19.36 | 0.8241 | 0.2657 | 21.95 | 0.7726 | 0.0833 |

| SNR [62] | 21.31 | 0.8564 | 0.1529 | 24.14 | 0.9028 | 0.0658 | 20.44 | 0.8641 | 0.0942 |

| LPNet [15] | 21.43 | 0.8019 | 0.0955 | 22.09 | 0.9014 | 0.1636 | 24.19 | 0.8916 | 0.0793 |

| URetinex-Net [16] | 21.33 | 0.8346 | 0.1084 | 23.50 | 0.8257 | 0.2282 | 21.33 | 0.8296 | 0.0861 |

| UFormer [31] | 19.25 | 0.7635 | 0.3029 | 18.82 | 0.7745 | 0.3134 | 23.64 | 0.8366 | 0.1563 |

| PairLlE [14] | 19.68 | 0.8233 | 0.1637 | 21.14 | 0.8107 | 0.2343 | 14.69 | 0.6398 | 0.1589 |

| Retformer [33] | 22.43 | 0.8183 | — | 22.94 | 0.8905 | 0.2147 | 23.67 | 0.8274 | — |

| LightenDiffusion [41] | 21.65 | 0.8047 | 0.1947 | 23.48 | 0.8155 | 0.2561 | 23.95 | 0.8927 | 0.0846 |

| QuadPrior [59] | 21.59 | 0.8142 | 0.2375 | 16.10 | 0.7624 | 0.2240 | 23.61 | 0.8277 | 0.1564 |

| CIDNet [30] | 22.59 | 0.8671 | 0.1766 | 25.70 | 0.9424 | 0.0562 | 24.43 | 0.8936 | 0.0846 |

| END [60] | 24.57 | 0.8207 | 0.2031 | 16.17 | 0.7714 | 0.2323 | 25.34 | 0.8361 | 0.0791 |

| Ours | 24.72 | 0.9078 | 0.1039 | 24.14 | 0.9077 | 0.1009 | 25.59 | 0.9346 | 0.0681 |

| Methods | DICM | LIME | VV | MEF | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIQE | PI | NIQMC | NIQE | PI | NIQMC | NIQE | PI | NIQMC | NIQE | PI | NIQMC | |

| LIME [54] | 3.836 | 3.264 | 4.952 | 4.637 | 2.994 | 4.881 | 5.672 | 3.023 | 5.326 | 3.499 | 2.778 | 4.979 |

| JED [11] | 4.287 | 3.319 | 4.893 | 5.304 | 3.384 | 4.895 | 4.014 | 2.982 | 5.035 | 4.741 | 3.309 | 4.951 |

| RetinexNet [18] | 3.862 | 3.181 | 4.634 | 5.518 | 3.427 | 4.531 | 3.278 | 2.244 | 4.959 | 4.355 | 2.902 | 4.572 |

| DSLR [19] | 3.513 | 3.326 | 5.097 | 4.372 | 3.262 | 5.015 | 3.4626 | 2.753 | 5.138 | 4.492 | 3.342 | 5.175 |

| LPNet [15] | 3.752 | 3.533 | 4.841 | 3.752 | 3.533 | 4.841 | 4.996 | 3.359 | 4.977 | 4.116 | 2.958 | 5.144 |

| Zero-DCE [28] | 3.169 | 3.055 | 4.896 | 3.169 | 3.055 | 4.896 | 3.261 | 2.501 | 5.370 | 3.369 | 2.429 | 4.943 |

| URetinex-Net [16] | 3.425 | 3.146 | 5.113 | 3.425 | 3.146 | 5.113 | 3.323 | 2.573 | 5.094 | 3.841 | 2.858 | 5.083 |

| MIRNet [56] | 3.384 | 3.528 | 5.061 | 4.625 | 3.028 | 4.937 | 3.513 | 2.774 | 5.106 | 4.045 | 3.097 | 5.036 |

| UFommer [31] | 5.054 | 2.954 | 4.885 | 7.927 | 3.061 | 4.893 | 5.308 | 2.963 | 4.687 | 4.258 | 2.946 | 4.857 |

| PairllE [14] | 4.016 | 2.893 | 4.791 | 4.519 | 2.813 | 4.773 | 4.269 | 2.846 | 4.293 | 4.337 | 2.861 | 4.839 |

| LightenDiffusion [41] | 3.741 | 3.132 | 5.106 | 3.968 | 3.016 | 4.762 | 2.968 | 2.553 | 4.837 | 3.843 | 2.961 | 4.927 |

| Ours | 2.816 | 2.553 | 5.219 | 4.826 | 3.758 | 5.364 | 4.681 | 2.438 | 5.522 | 4.637 | 2.439 | 5.274 |

| Method | AG | LVar | LSTD | BD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RetinexNet [18] | 5.149 | 3.101 | 1.062 | 7.342 | 0.273 |

| KinD [58] | 6.123 | 2.342 | 1.002 | 6.206 | 0.231 |

| END [60] | 6.554 | 2.657 | 2.374 | 5.110 | 0.159 |

| Zero-DCE [28] | 5.221 | 1.697 | 1.010 | 7.091 | 0.139 |

| SNR [62] | 6.335 | 2.997 | 1.892 | 2.310 | 0.173 |

| CIDNet [30] | 6.687 | 3.028 | 0.994 | 3.740 | 0.211 |

| LightenDiffusion [41] | 5.908 | 5.017 | 1.930 | 5.107 | 0.193 |

| EnlightenGAN [27] | 5.712 | 1.101 | 2.371 | 4.529 | 0.123 |

| PairLIE [14] | 5.826 | 2.017 | 1.909 | 4.937 | 0.187 |

| DSLR [19] | 5.290 | 4.007 | 2.062 | 4.387 | 0.208 |

| UFormer [31] | 5.250 | 3.394 | 2.107 | 4.320 | 0.118 |

| URetinex-Net [31] | 5.937 | 1.997 | 4.004 | 7.863 | 0.211 |

| Ours | 7.358 | 1.075 | 0.937 | 3.871 | 0.109 |

| Method | Param (M) | Flops (G) | Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RetinexNet [18] | 1.23 | 6.79 | 0.5217 |

| KinD [58] | 8.49 | 7.44 | 0.6445 |

| END [60] | 8.36 | 270.42 | 0.7963 |

| Zero-DCE [28] | 1.21 | 5.21 | 0.0079 |

| SNR [62] | 4.01 | 26.35 | 0.5141 |

| CIDNet [30] | 1.98 | 8.03 | 0.7869 |

| LightenDiffusion [41] | 101.71 | 210G | 1.2001 |

| EnlightenGAN [27] | 8.64 | 7.88 | 0.6501 |

| PairLIE [14] | 2.16 | 19.24 | 0.2971 |

| DSLR [19] | 14.31 | 22.95 | 0.9210 |

| UFormer [31] | 5.20 | 10.68 | 0.6298 |

| URetinex-Net [31] | 26.27 | 90.61 | 0.8902 |

| Ours | 1.99 | 8.24 | 0.1009 |

| Ablated Model | MIT-Adobe 5K | LOL-v1 | LOL-v2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR | SSIM | LPIPS | PSNR | SSIM | LPIPS | PSNR | SSIM | LPIPS | |

| -w/o RCAB | 21.30 | 0.738 | 0.071 | 20.81 | 0.793 | 0.187 | 23.12 | 0. 812 | 0.167 |

| -w/o CSA | 22.52 | 0.804 | 0.089 | 23.19 | 0.806 | 0.174 | 23.91 | 0.878 | 0.157 |

| -w/o CCB | 23.09 | 0.831 | 0.106 | 22.14 | 0.855 | 0.187 | 23.68 | 0.893 | 0.169 |

| full model | 25.59 | 0.934 | 0.067 | 24.72 | 0.903 | 0.102 | 24.14 | 0.908 | 0.101 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lu, H.; Qian, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z. Multi-Scale Interactive Network with Color Attention for Low-Light Image Enhancement. Sensors 2026, 26, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010083

Lu H, Qian C, Wang Z, Liu Z. Multi-Scale Interactive Network with Color Attention for Low-Light Image Enhancement. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010083

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Haoxiang, Changna Qian, Ziming Wang, and Zhenbing Liu. 2026. "Multi-Scale Interactive Network with Color Attention for Low-Light Image Enhancement" Sensors 26, no. 1: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010083

APA StyleLu, H., Qian, C., Wang, Z., & Liu, Z. (2026). Multi-Scale Interactive Network with Color Attention for Low-Light Image Enhancement. Sensors, 26(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010083